University Teacher Students’ Learning in Times of COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

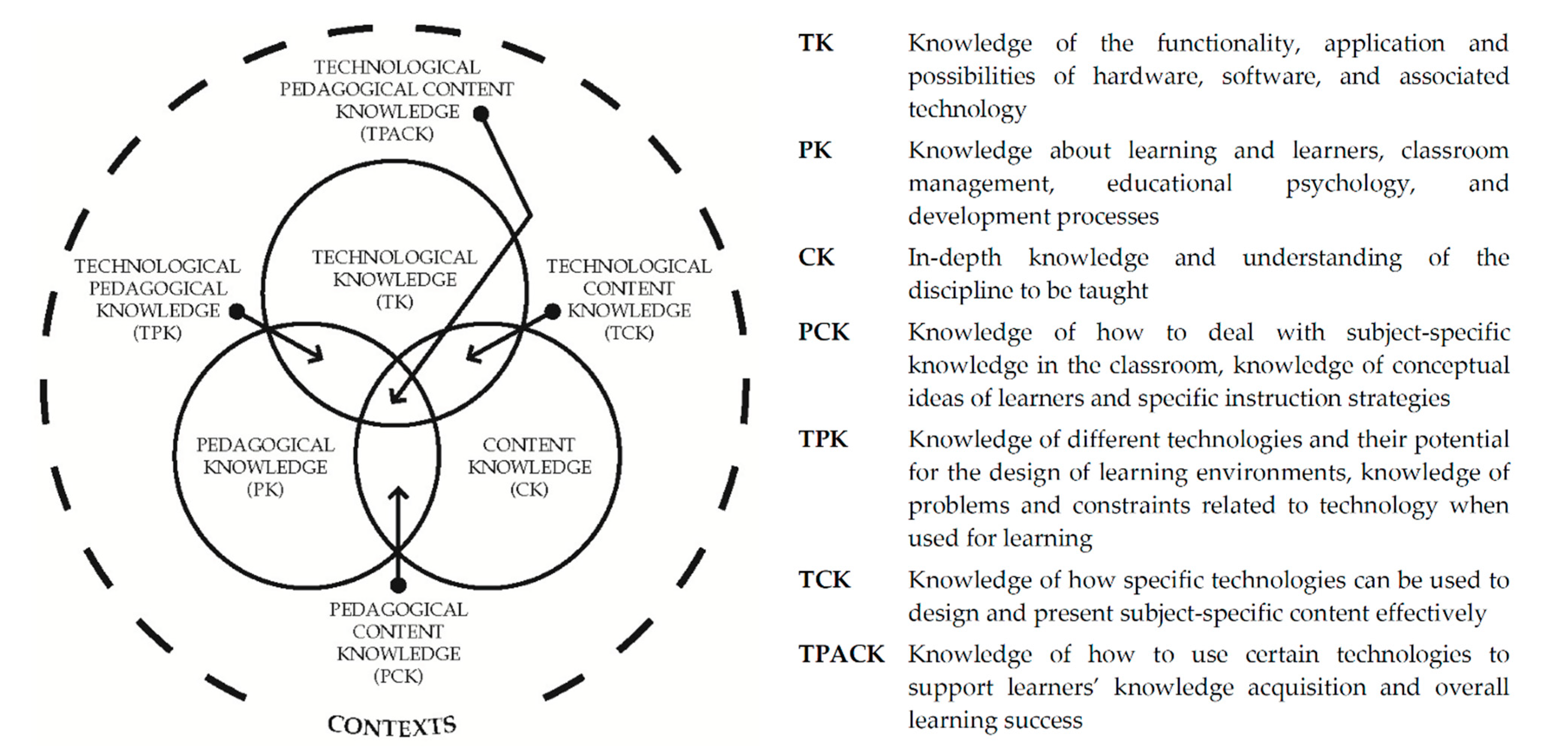

1.1. Teachers’ Professional Knowledge and Digital Skills

- Content knowledge (CK) describes in-depth knowledge and understanding of the teaching subject that enables teachers to organize lessons successfully and monitor the students’ learning progress adequately in terms of the subject’s content.

- Pedagogical knowledge (PK) is regarded as being interdisciplinary and refers to knowledge about learning and learners, classroom management, educational psychology, and development processes.

- Pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) refers to a specific transformation of CK, intending an effective and flexible use in the classroom to make the content understandable to the learners. This combination of CK and PK elements constitutes PCK as a specific domain of professional knowledge, whose theoretically assumed independence has also been confirmed empirically in the meantime [35,36]. PCK includes aspects such as knowledge about conceptual ideas of learners or specific instruction strategies.

1.2. Digital Teaching and Learning before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic

1.3. Research Questions

- RQ1: Do two comparable groups of teacher students, of which one was surveyed before and the other after switching to distance learning, show differences regarding their self-concept of professional knowledge? Additionally, if that should be the case, are such differences to the disadvantage of the group surveyed after switching to distance learning?

- RQ2: Do the two groups considered in RQ1 score differently regarding main personality characteristics? Does the group surveyed after switching to distance learning, for example, score higher on neuroticism (sensitivity/nervousness), and if that should be the case, do such differences suggest any clarification regarding RQ1?

- RQ3: What are teacher student’s perceptions of distance learning? How do they evaluate factors associated with successful teaching and learning at the end of the first semester of distance learning (spring semester 2020)? How could their digital competence and attitude towards digital teaching and learning be characterized? How do they rate the technical conditions? Do they report specific handicaps at that time?

- RQ4: How could teacher students’ view of their own person and confidence in their own abilities be characterized in spring semester 2020? Are their core self-evaluations congruent with those of a reference sample or do they deviate significantly?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study 1

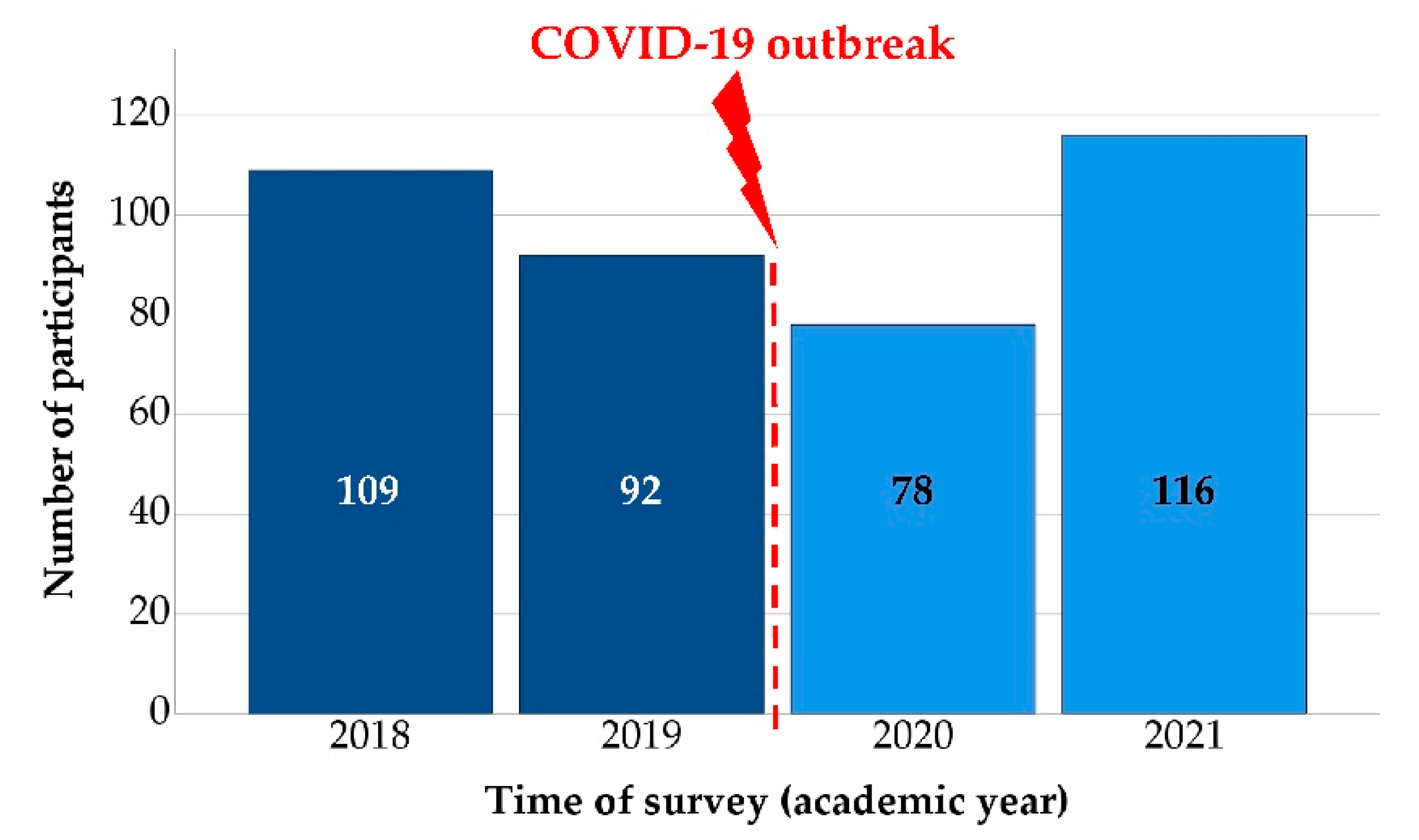

2.1.1. Sample and Procedure

2.1.2. Self-Concept of Professional Knowledge in Biology Questionnaire

2.1.3. NEO Five-Factor Inventory

- Neuroticism (sensitive/nervous vs. resilient/confident);

- Extraversion (outgoing/energetic vs. solitary/reserved);

- Openness to experience (inventive/curious vs. consistent/cautious);

- Agreeableness (friendly/compassionate vs. critical/rational);

- Conscientiousness (efficient/organized vs. extravagant/careless).

2.1.4. Statistical Methods

2.2. Study 2

2.2.1. Sample and Procedure

2.2.2. Perception of Distance Learning Questionnaire

- Successful teaching and learning: This subscale consisted of 17 items, covering relevant aspects relating to successful teaching and learning [32], e.g., encouragement of the learners to reflect on individual learning progress, reply to learners’ questions, or fit between teaching formats and learning objectives. Each of these items should be rated twice. On the one hand, the teacher students were asked to give an absolute rating on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = highly unsatisfactory to 4 = highly satisfactory). On the other hand, they were asked to rate these aspects when comparing them to previous semesters of regular on-site learning (−1 = inferior to on-site learning to +1 = superior to on-site learning). Homogeneities of both subscales were α = 0.90 (absolute rating) and α = 0.93 (comparison to on-site learning) in our sample.

- Attitude towards digital teaching and learning: This subscale consisted of 9 items, covering relevant aspects relating to the teacher students’ view of e-learning, e.g., potential to learn more flexibly or reduction of effort for learners and teachers. These items should be rated each on a bipolar scale (1 = strongly disagree to 10 = strongly agree). Homogeneity of this subscale was α = 0.93 in our sample.

- Technical conditions: This subscale consisted of 6 items, covering the teacher students’ view of relevant technology-related aspects of e-learning, e.g., usability, technical support, or accessibility of courses. These items should be rated each on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very poor to 5 = very good). Homogeneity of this subscale was α = 0.69 in our sample.

- Digital skills: This subscale consisted of 13 items, covering the teacher students’ self-concept of digital skills [43], e.g., abilities to use e-learning platforms, protect own digital data, or reflect on own usage behavior. These items should be rated each on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). The homogeneity of the subscale was α = 0.81 in our sample.

- Handicaps: This supplementary question related to 10 categories, representing potential handicaps of the teacher students during the first semester of distance learning, e.g., infection with COVID-19, increased psychological stress, or financial problems. For each of these handicaps the students were asked to state whether it applied to them or not, so a selection of several categories was possible for every participant.

2.2.3. Core Self-Evaluations Scale

2.2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study 1

3.1.1. Self-Concept of Professional Knowledge

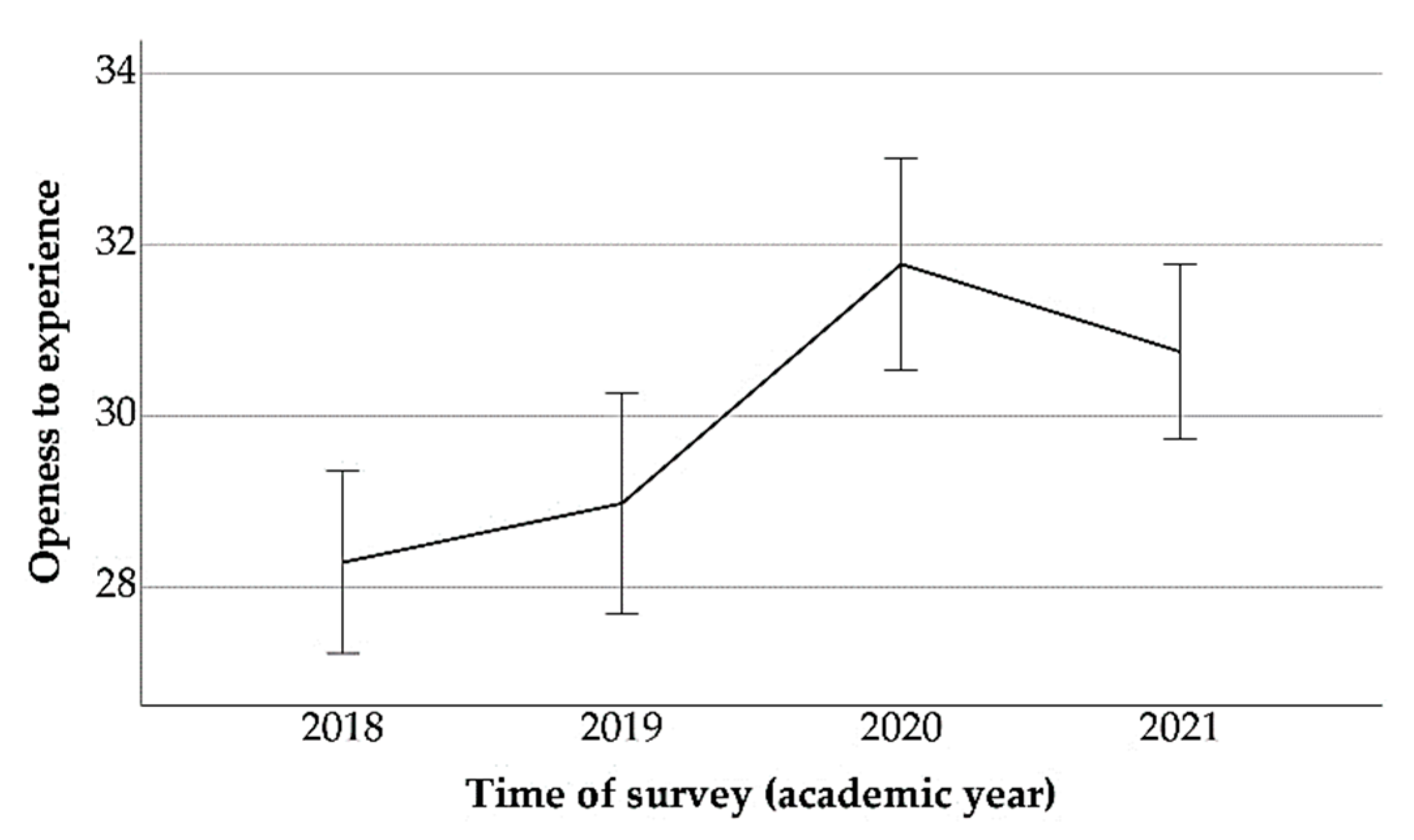

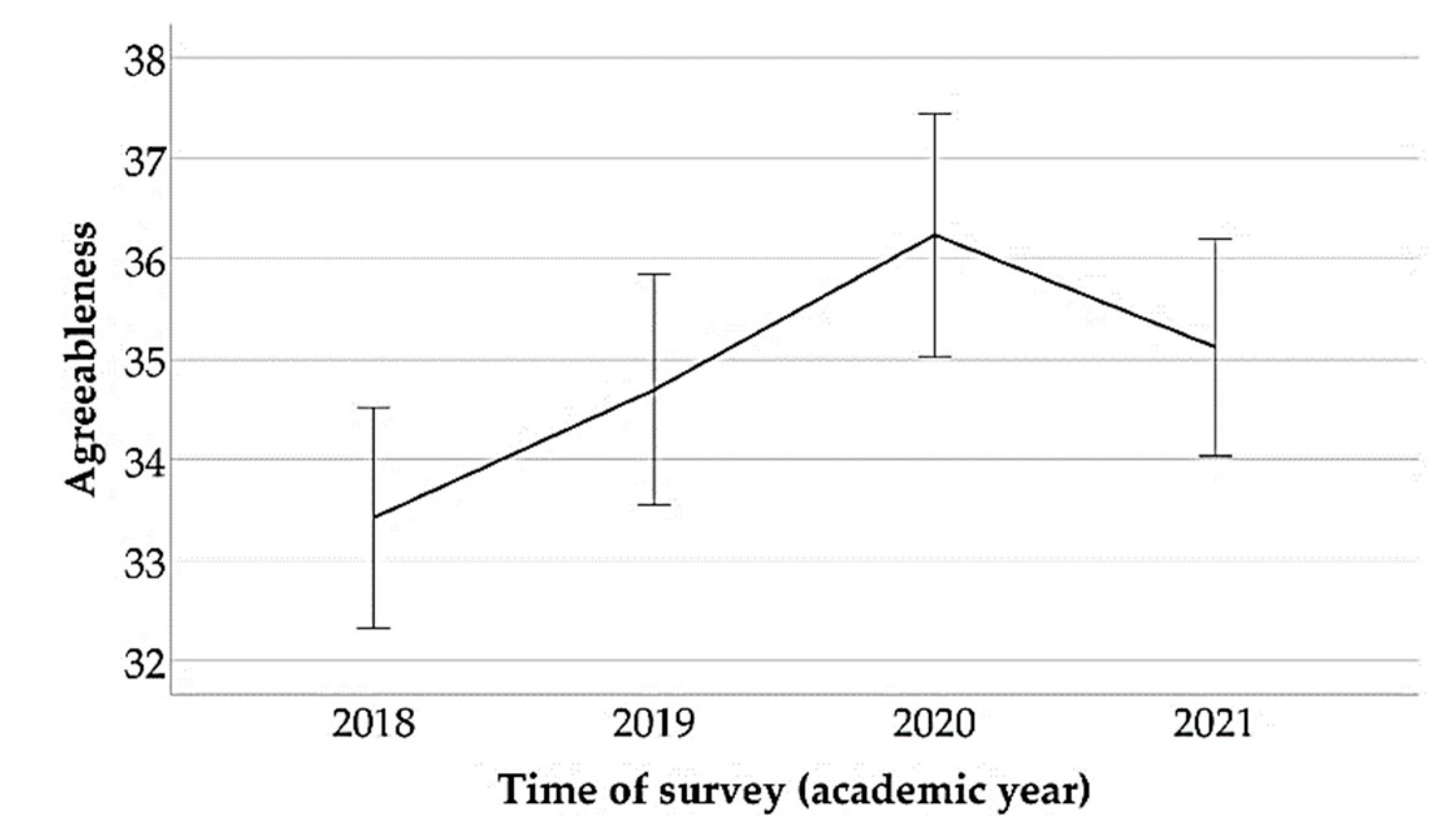

3.1.2. Big Five Personality Characteristics

3.2. Study 2

3.2.1. Perceptions of Distance Learning

3.2.2. Core Self-Evaluations

3.2.3. Additional Correlational Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Study 1

4.2. Study 2

4.3. Summary

4.4. Practical Implications and Recommendations

4.5. Limitations and Prospects for Future Research

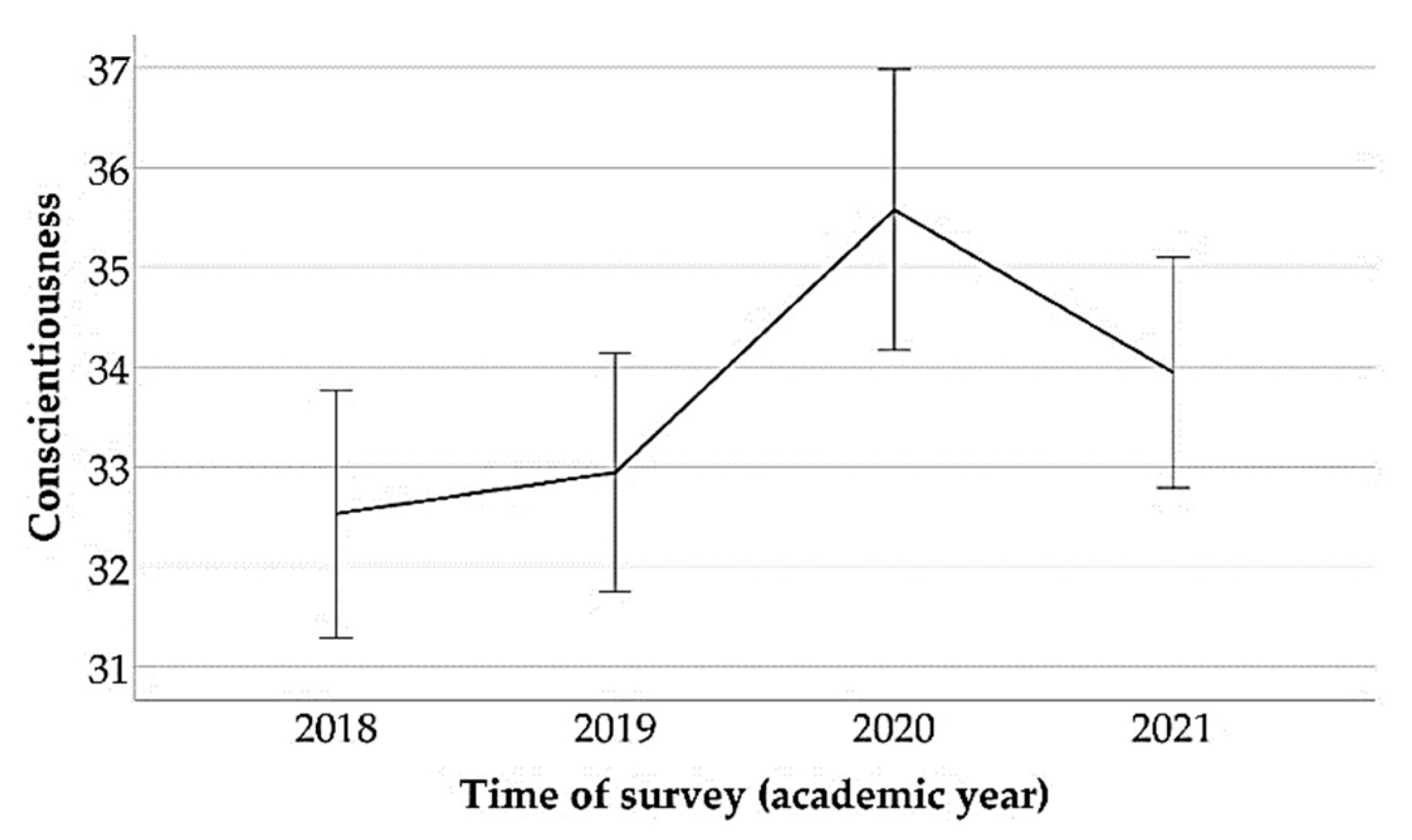

- Study 1 was not based on a longitudinal design that would be necessary to validly determine changes over time. Therefore, the results must be interpreted with caution in this regard, although resulting impairment of internal validity could be reduced by (1) comparability of the cohorts on relevant potentially confounding variables regarding the TPACK dimensions [38] and (2) visual inspection of the line diagrams that visualize the NEO-FFI scores [90] over the course of the four academic years considered (see Section 2.1.1 and Section 3.1).

- Professional knowledge was not assessed directly (i.e., objective performance measure) in study 1. Instead, we decided to assess the teacher students’ self-concept of knowledge (see Section 2.1.2), aiming at subsequently drawing conclusions about their factual performance. The reason for this was our intention to keep the burden on participants as low as possible. Nevertheless, we do not assume that this approach significantly affected internal validity of our conclusions, since self-concept of abilities and academic achievement are usually moderately to highly correlated [24,25,29,30], so it can be assumed that self-assessment is a valid indicator of academic achievement. Nevertheless, in future studies, it would be desirable to assess objective performance parameters additionally, since such an approach would probably allow for more accurate identification of specific starting points of corrective interventions.

- Regardless of the optimal statistical power of 0.80 of our statistical analyses within study 2, we surveyed a comparatively small sample of N = 84 teacher students of only one German university (see Section 2.2.1), which undoubtedly limits the generalizability of our results. Furthermore, study 2 was based on only one cross-sectional measure. Accordingly, although we were able to realize our intention to get a valid overview regarding the evaluation of the first semester of distance learning, no further conclusions can be drawn with respect to development of variables over time.

- With respect to the different samples of both studies, it should finally be noted that although study 2 provides useful initial suggestions regarding the interpretation of the results from study 1, the respective participants can only be compared to a limited extent, since the teacher students in study 2, on average, had already completed one additional year of university teacher training and were partly enrolled in different teaching subjects (see Section 2.2.1).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bujard, M.; von den Driesch, E.; Ruckdeschel, K.; Laß, I.; Thönnissen, C.; Schumann, A.; Schneider, N.F. Belastungen von Kindern, Jugendlichen und Eltern in der Corona-Pandemie [Burdens on children, adolescents and parents in the corona pandemic]. BiB. Bevölkerungs. Stud. 2021, 2, 1–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeaka, H.; Anumudu, C.K.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Egele-Godswill, E.; Mbaegbu, P. COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakose, T.; Yirci, R.; Papadakis, S.; Ozdemir, T.Y.; Demirkol, M.; Polat, H. Science Mapping of the Global Knowledge Base on Management, Leadership, and Administration Related to COVID-19 for Promoting the Sustainability of Scientific Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, S.; Heyer, L.; Lips, A.; Rusack, T.; Schröer, W.; Thomas, S.; Wilmes, J. Das Leben von Jungen Menschen in der Corona-Pandemie. Erfahrungen, Sorgen, Bedarfe [The Lives of Young People in Times of the Corona Pandemic. Experiences, Worries, Needs], 1st ed.; Stiftung, B., Ed.; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/Projekte/Familie_und_Bildung/Studie_WB_Das_Leben_von_jungen_Menschen_in_der_Corona-Pandemie_2021.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Rudert, S.; Gleibs, I.; Gollwitzer, M.; Häfner, M.; Hajek, K.; Harth, N.; Häusser, J.; Imhoff, R.; Schneider, D. Us and the virus: Understanding the COVID-19 pandemic through a social psychological lens. Eur. Psychol. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Welter, V.D.E.; Welter, N.G.E.; Großschedl, J. Experience and Health-Related Behavior in Times of the Corona Crisis in Germany: An Exploratory Psychological Survey Considering the Identification of Compliance-Enhancing Strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Mukta, M.S.H.; Muntasir, F.; Rahman, S.; Islam, A.K.M.N.; Ali, M.E. Can COVID-19 Change the Big5 Personality Traits of Healthcare Workers? In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Networking, Systems and Security, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 22–24 December 2020; pp. 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sutin, A.R.; Luchetti, M.; Aschwanden, D.; Lee, J.H.; Sesker, A.A.; Strickhouser, J.E.; Stephan, Y.; Terracciano, A. Change in five-factor model personality traits during the acute phase of the coronavirus pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; John, O.P. An Introduction to the Five-Factor Model and Its Applications. J. Pers. 1992, 60, 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, J.; Egloff, B.; Schmukle, S.C. Stability and change of personality across the life course: The impact of age and major life events on mean-level and rank-order stability of the Big Five. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 862–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrel, B. Is COVID-19 Changing How People Score on Personality Assessments? Available online: https://www.hoganassessments.com/blog/is-covid-19-changing-how-people-score-on-personality-assessments/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- UNESCO; UNICEF; The World Bank; OECD. What’s Next? Lessons on Education Recovery: Findings from a Survey of Ministries of Education Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/lessons_on_education_recovery.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Goertz, L.; Hense, J. Studie zu Veränderungsprozessen in Unterstützungsstrukturen für Lehre an Deutschen Hochschulen in der Corona-Krise [Study on Changes in Supporting Structures for Teaching at German Universities during the Corona Crisis]; working paper 56; Hochschulforum Digitalisierung: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://hochschulforumdigitalisierung.de/sites/default/files/dateien/HFD_AP_56_Support-Strukturen_Lehre_Corona_mmb.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Dorn, E.; Hancock, B.; Sarakatsannis, J.; Viruleg, E. COVID-19 and Student Learning in the United States: The Hurt Could Last a Lifetime; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-student-learning-in-the-united-states-the-hurt-could-last-a-lifetime (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Grewenig, E.; Lergetporer, P.; Werner, K.; Woessmann, L.; Zierow, L. COVID-19 and educational inequality: How school closures affect low- and high-achieving students. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2021, 140, 103920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerstein, S.; König, C.; Dreisörner, T.; Frey, A. Effects of COVID-19-Related School Closures on Student Achievement: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 746289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, F.; Schons, C.; Scheuerer, S.; Gritzmann, P.; Richter-Gebert, J.; Reiss, K. Einfluss motivational-emotionaler Orientierungen auf die Bewältigung selbstregulatorischer Anforderungen beim Lernen tertiärer Mathematik in Zeiten der COVID-19-Pandemie [Influence of motivational-emotional orientations on coping with self-regulatory requirements when learning tertiary mathematics in times of the COVID-19 pandemic]. In Bildung und Corona [Education and Corona], Proceedings of the Digital Conference Year of the Society for Empirical Educational Research, Digital Conference, Germany, 22–23 April 2021; DIPF|Leibniz-Institut für Bildungsforschung und Bildungsinformation: Frankfurt, Germany, 2021; pp. 104–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bosse, E.; Lübcke, M.; Book, A.; Würmseer, G. Corona@Hochschule: Befragung von Hochschulleitungen zur (Digitalen) Lehre [Corona@University: Survey of University Management on (Digital) Teaching]; HIS-Institut für Hochschulentwicklung: Hannover, Germany, 2020; ISBN 978-3948388089. [Google Scholar]

- Fickermann, D.; Edelstein, B. Editorial: “Langsam vermisse ich die Schule...”—Schule während und nach der Corona-Pandemie [Editorial: “I’m starting to miss school…”—Schooling during and after the Corona pandemic]. In “Langsam Vermisse ich Die Schule...” —Schule Während und nach der Corona-Pandemie [“I’m Starting to Miss School…”—Schooling during and after the Corona Pandemic]; Die Deutsche Schule, Supplement 16; Fickermann, D., Edelstein, B., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2020; pp. 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- Holz, G.; Richter-Kornweitz, A. Corona-Chronik: Gruppenbild Ohne (Arme) Kinder—Eine Streitschrift [Corona Chronicle: Group Picture without (Poor) Children—A Pamphlet]; Institut für Sozialarbeit und Sozialpädagogik: Frankfurt, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://www.iss-ffm.de/fileadmin/assets/themenbereiche/downloads/Corona-Chronik_Streitschrift_final.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Neumann, S. Nicht Systemrelevant? Die Sicht Junger Menschen auf Die Corona-Krise [Not Relevant for the System? The View of Young People on the Corona Crisis]; Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg: Halle, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://sozpaed-corona.de/nicht-systemrelevant-die-sicht-junger-menschen-auf-die-corona-krise/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Schult, J.; Mahler, N.; Fauth, B.; Lindner, M.A. Did Students Learn Less During the COVID-19 Pandemic? Reading and Mathematics Competencies Before and After the First Pandemic Wave. PsyArXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Byrne, B.M.; Shavelson, R.J. A Multifaceted Academic Self-Concept: Its Hierarchical Structure and Its Relation to Academic Achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 1988, 80, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Yeung, A.S. Causal Effects of Academic Self-Concept on Academic Achievement: Structural Equation Models of Longitudinal Data. J. Educ. Psychol. 1997, 89, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calsyn, R.J.; Kenny, D.A. Self-concept of Ability and Perceived Evaluation of Others: Cause or Effect of Academic Achievement? J. Educ. Psychol. 1977, 69, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, H.W.; Craven, R.G. Reciprocal Effects of Self-Concept and Performance from a Multidimensional Perspective. Beyond Seductive Pleasure and Unidimensional Perspectives. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 1, 133–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, H.W.; Trautwein, U.; Lüdtke, O.; Köller, O.; Baumert, J. Academic Self-Concept, Interest, Grades, and Standardized Test Scores: Reciprocal Effects Models of Causal Ordering. Child Dev. 2005, 76, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, M.; Parker, P.; Marsh, H.W.; Craven, R.G.; Yeung, A.S. The reciprocal relations between self-concept, motivation and achievement: Juxtaposing academic self-concept and achievement goal orientations for mathematics success. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 34, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, J.; Trautwein, U. Selbstkonzept [Self-concept]. In Pädagogische Psychologie [Educational Psychology], 2nd ed.; Wild, E., Möller, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, J.C.; DuBois, D.L.; Cooper, H. The Relation between Self-Beliefs and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Review. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 39, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, W.L.; Wright, S.P.; Horn, S.P. Teacher and Classroom Context Effects on Student Achievement: Implications for Teacher Evaluation. J. Pers. Eval. Educ. 1997, 11, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J.A.C. Visible Learning. A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0415476171. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L.S. Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res. 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1987, 57, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gess-Newsome, J.; Lederman, N.G. Examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge. The Construct and Its Implications for Science Education, 1st ed.; Kluwer: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0792359036. [Google Scholar]

- Großschedl, J.; Welter, V.; Harms, U. A new instrument for measuring pre-service biology teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge: The PCK-IBI. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2019, 56, 402–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baumert, J.; Kunter, M. The COACTIV model of teachers’ professional competence. In Cognitive Activation in the Mathematics Classroom and Professional Competence of Teachers: Results from the COACTIV Project, 1st ed.; Kunter, M., Baumert, J., Blum, W., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., Neubrand, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.A.; Baran, E.; Thompson, A.D.; Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J.; Shin, T.S. Technological Pedagogical Content knowledge (TPACK): The Development and Validation of an Assessment Instrument for Preservice Teachers. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2009, 42, 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, C.; Valanides, N. Epistemological and methodological issues for the conceptualization, development, and assessment of ICT-TPCK: Advances in Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK). Comput. Educ. 2009, 52, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M.J.; Mishra, P.; Cain, W. What is Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)? J. Educ. 2013, 193, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koehler, M.J.; Mishra, P.; Yahya, K. Tracing the development of teacher knowledge in a design seminar: Integrating content, pedagogy and technology. Comput. Educ. 2007, 49, 740–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redecker, C. European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators: DigCompEdu; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; ISBN 978-9279737183.

- Caena, F.; Redecker, C. Aligning teacher competence frameworks to 21st century challenges: The case for the European Digital Competence Framework for Educators (Digcompedu). Eur. J. Educ. 2019, 54, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung. Bildungsoffensive für Die Digitale Wissensgesellschaft: Strategie des Bundesministeriums für Bildung und Forschung [Educational Offensive towards Digital Knowledge Society: Strategy of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research]; BMBF: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/pdf/Themen/Digitale-Welt/Bildungsoffensive_fuer_die_digitale_Wissensgesellschaft.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung. Neue Wege in der Lehrerbildung: Die Qualitätsoffensive Lehrerbildung [New Paths in Teacher Education: The Qualitätsoffensive Lehrerbildung]; BMBF: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://ql.bmbfcluster.de/files/Neue_Wege_in_der_Lehrerbildung.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Sturm, T. Begriffliche Perspektiven auf Unterschiede und Ungleichheit im schulpädagogischen Diskurs—eine kritische Reflexion [Conceptual perspectives on differences and inequality in educational discourse—a critical reflection]. In Dealing with Diversity: Innovative Lehrkonzepte in der Lehrer*Innenbildung zum Umgang Mit Heterogenität und Inklusion [Dealing with Diversity: Innovative Teaching Concepts in Teacher Training for Dealing with Heterogeneity and Inclusion], 1st ed.; Rott, D., Zeuch, N., Fischer, C., Souvignier, E., Terhart, E., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2018; Volume 6, pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Inklusion und Bildung: Für Alle Heißt für Alle [Inclusion and Education: For Everyone Means for Everyone]; Deutsche UNESCO-Kommission: Bonn, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://www.unesco.de/sites/default/files/2020-06/weltbildungsbericht_2020_kurzfassung.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Harvey, M.W.; Yssel, N.; Bauserman, A.D.; Merbler, J.B. Preservice Teacher Preparation for Inclusion: An Exploration of Higher Education Teacher-Training Institutions. Remedial. Spec. Educ. 2008, 31, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algermissen, P.; Hauser, M.; van Ledden, H. Inklusion ist (k)eine Frage der Persönlichkeit: Inklusive Kompetenzen institutionell verankern! [Inclusion is (not) a question of personality: Anchoring inclusive competencies institutionally!] QfI-Qualif. Für Inkl. 2020, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, A.-K.; Werning, R. Inklusive Schul- und Unterrichtsentwicklung [Inclusive development of school and lessons]. In Lehrer-Schüler-Interaktion: Inhaltsfelder, Forschungsperspektiven und Methodische Zugänge [Teacher-Student Interaction: Content Fields, Research Perspectives and Methodological Approaches], 3rd ed.; Schweer, M.K.W., Ed.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 607–623. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, D.; Brauns, S.; Sellin, K.; Barth, M.; Abels, S. Professionalisierung von Lehramtsstudierenden für inklusiven naturwissenschaftlichen Unterricht [Professionalization of teacher students for inclusive science teaching]. J. Für Psychol. 2019, 27, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Lehren aus der Pandemie: Gleiche Chancen für Alle Kinder und Jugendlichen Sichern [Lessons from the Pandemic: Ensuring Equal Opportunities for All Children and Adolescents]; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/a-p-b/17249.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Agasisti, T.; Frattini, F.; Soncin, M. Digital Innovation in Times of Emergency: Reactions from a School of Management in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klieme, E. Guter Unterricht—auch und besonders unter Einschränkungen der Pandemie? [Good teaching—also and especially under the restrictions of the pandemic?]. In “Langsam Vermisse ich Die Schule... ”—Schule Während und nach der Corona-Pandemie [“I’m Starting to Miss School…”—Schooling during and after the Corona Pandemic]; Die Deutsche Schule, Supplement 16; Fickermann, D., Edelstein, B., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2020; pp. 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwka, A.; Klopsch, B. Disruptive Innovation! Wie die Pandemie die “Grammatik der Schule” herausfordert und welche Chancen sich jetzt für eine “Schule ohne Wände” in der digitalen Wissensgesellschaft bieten [Disruptive innovation! How the pandemic challenges the “grammar of the school” and what opportunities are available now for a “school without walls” in the digital knowledge society]. In “Langsam Vermisse ich Die Schule...”—Schule Während und nach der Corona-Pandemie [“I’m Starting to Miss School…”—Schooling during and after the Corona Pandemic]; Die Deutsche Schule, Supplement 16; Fickermann, D., Edelstein, B., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2020; pp. 216–229. [Google Scholar]

- Blaskó, Z.; da Costa, P.; Schnepf, S.V. Learning Loss and Educational Inequalities in Europe: Mapping the Potential Consequences of the COVID-19 Crisis; Institut zur Zukunft der Arbeit: Bonn, Germany, 2021; Available online: http://ftp.iza.org/dp14298.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Engzell, P.; Frey, A.; Verhagen, M.D. Learning Loss Due to School Closures During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2022376118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helm, C.; Huber, S.; Loisinger, T. Was wissen wir über schulische Lehr-Lern-Prozesse im Distanzunterricht während der Corona-Pandemie?—Evidenz aus Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz [What do we know about school teaching-learning processes in distance teaching during the corona pandemic?—Evidence from Germany, Austria and Switzerland]. Z Erzieh. 2021, 24, 237–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, J.P.; Hasan, A.; Goldemberg, D.; Iqbal, S.A.; Geven, K. Simulating the Potential Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures on Schooling and Learning Outcomes: A Set of Global Estimates. Available online: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/1813-9450-9284 (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Anger, C.; Plünnecke, A. Schulische Bildung in Zeiten der Corona-Krise: Bildungsdefizite Schnell Beheben [School Education in Times of the Corona Crisis: Rectifying Educational Deficits Quickly]; Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft: Köln, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://www.iwkoeln.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Studien/Gutachten/PDF/2021/Kurzstudie_INSM_Bildungsmonitor.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Bailey, D.; Duncan, G.J.; Murnane, R.J.; Yeung, N.A. Achievement Gaps in the Wake of COVID-19. Educ. Res. 2021, 50, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ackeren, I.; Endberg, M.; Locker-Grütjen, O. Chancenausgleich in der Corona-Krise: Die soziale Bildungsschere wieder schließen [Equal opportunities in times of the Corona crisis: Closing the social education gap again]. Die Dtsch. Sch. 2020, 112, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.; Fischer-Ontrup, C.; Schuster, C. Individuelle Förderung und selbstreguliertes Lernen: Bedingungen und Optionen für das Lehren und Lernen in Präsenz und auf Distanz [Individual support and self-regulated learning: Conditions and options for teaching and learning on-site and at a distance]. In “Langsam Vermisse ich Die Schule...”—Schule Während und nach der Corona-Pandemie [“I’m Starting to Miss School…”—Schooling during and after the Corona Pandemic]; Die Deutsche Schule, Supplement 16; Fickermann, D., Edelstein, B., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2020; pp. 136–152. [Google Scholar]

- Züchner, I.; Jäkel, H.R. Fernbeschulung während der COVID-19 bedingten Schulschließungen weiterführender Schulen: Analysen zum Gelingen aus Sicht von Schülerinnen und Schülern [Remote schooling during the COVID-19-related closings of secondary schools: Analyses of success from the perspective of pupils]. Z Erzieh. 2021, 24, 479–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenstern, A.; Walz, K. Hochschulbildung im Spannungsfeld von digitaler Kommunikation und virtuellen Lernumwelten [University education in the field of tension between digital communication and virtual learning environments]. In (Digitale) Präsenz—Ein Rundumblick auf das Soziale Phänomen Lehre [(Digital) Presence—A Panoramic View on the Social Phenomenon of Teaching], 1st ed.; Stanisavljevic, M., Tremp, P., Eds.; Pädagogische Hochschule Luzern: Luzern, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Geis-Thöne, W.; Plünnecke, A. Auswirkungen der Corona-Pandemie auf Die Bildungsgerechtigkeit: Ein Blick auf Die Bildungswege Junger Erwachsener [Effects of the Corona Pandemic on Equity in Education: A Look at the Educational Pathways of Young Adults]; Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft: Köln., Germany, 2021; Available online: https://www.insm.de/fileadmin/insm-dms/text/publikationen/Bildungsmonitor_2021/2021-04-29_INSM_Corona_und_Bildungsgerechtigkeit_Final.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Zancajo, A. The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Education: Rapid Review of the Literature; School of Education, University of Glasgow: Glasgow, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/publications/covid-decade-impact-of-the-pandemic-on-education/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Borgwardt, A. “… und es Hat Zoom Gemacht."—Studierende im Dritten Digitalsemester: Situation und Perspektiven [“... and It Did Zoom."—Students within the Third Digital Semester: Situation and Perspectives]; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/a-p-b/18012.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Breitenbach, A. Digitale Lehre in Zeiten von Covid-19: Risiken und Chancen [Digital Teaching in Times of Covid-19: Risks and Opportunities]; Institut für Soziologie, Philipps-Universität Marburg: Marburg, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2021/21274/pdf/Breitenbach_2021_Digitale_Lehre_in_Zeiten.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Godoy, L.D.; Falcoski, R.; Incrocci, R.M.; Versuti, F.M.; Padovan-Neto, F.E. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Remote Learning in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traus, A.; Höffken, K.; Thomas, S.; Mangold, K.; Schröer, W. Stu.diCo.—Studieren Digital in Zeiten von Corona [Stu.diCo.—Studying Digital in Times of Corona]; Universitätsverlag Hildesheim: Hildesheim, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:gbv:hil2-opus4-11578 (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Porsch, R.; Reintjes, C.; Görich, K.; Paulus, D. Pädagogische Medienkompetenzen und ICT-Beliefs von Lehramtsstudierenden: Veränderungen während eines “digitalen Semesters”? [Pedagogical media skills and ICT beliefs of student teachers: Changes during a “digital semester”?]. In Das Bildungssystem in Zeiten der Krise: Empirische Befunde, Konsequenzen und Potenziale für das Lehren und Lernen [The Education System in Times of Crisis: Empirical Findings, Consequences and Potential for Teaching and Learning], 1st ed.; Reintjes, C., Porsch, R., im Brahm, G., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2021; pp. 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Schaumburg, H. Chancen und Risiken Digitaler Medien in der Schule. Medienpädagogische und -Didaktische Perspektiven [Opportunities and Risks of Digital Media in Schools. Media Educational and Didactic Perspectives]; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/Studie_IB_Chancen_Risiken_digitale_Medien_2015.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- van Ackeren, I.; Aufenanger, S.; Eickelmann, B.; Friedrich, S.; Kammerl, R.; Knopf, J.; Mayrberger, K.; Scheika, H.; Scheiter, K.; Schiefner-Rohs, M. Digitalisierung in der Lehrerbildung: Herausforderungen, Entwicklungsfelder und Förderung von Gesamtkonzepten [Digitization in teacher training: Challenges, areas of development, and promotion of overall concepts]. Die Dtsch. Sch. 2019, 111, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koşar, G. Distance Teaching Practicum: Its Impact on Pre-Service EFL Teachers’ Preparedness for Teaching. IAFOR J. Educ. 2021, 9, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer Keefe, E. Learning to Practice Digitally: Advancing Preservice Teachers’ Preparation via Virtual Teaching and Coaching. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2020, 28, 223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Kerres, M. Against All Odds: Education in Germany Coping with Covid-19. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmke, A.; Helmke, T. Unterrichtsdiagnostik als Ausgangspunkt für Unterrichtsentwicklung [Lesson diagnostics as a starting point for lesson development]. In Handbuch Unterrichtsentwicklung [Handbook Lesson Development], 1st ed.; Rolff, H.-G., Ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2015; pp. 242–257. [Google Scholar]

- Postholm, M.B. Classroom Management: What Does Research Tell Us? Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 12, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, B.S.; Hirn, R.G.; Lewis, T.J. Enhancing Effective Classroom Management in Schools: Structures for Changing Teacher Behavior. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 2017, 40, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choate, K.; Goldhaber, D.; Theobald, R. The effects of COVID-19 on teacher preparation. Phi Delta Kappan 2021, 102, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donitsa-Schmidt, S.; Ramot, R. Opportunities and challenges: Teacher education in Israel in the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Educ. Teach. 2020, 46, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, D.; Veber, M.; Gollub, P. Perspektiven von angehenden Lehrpersonen auf pädagogische Medienkompetenzen in Zeiten digitalen Lehrens und Unterrichtens [Pre-service teachers’ perspectives on pedagogical media skills in times of digital teaching and instruction]. In Das Bildungssystem in Zeiten der Krise: Empirische Befunde, Konsequenzen und Potenziale für das Lehren und Lernen [The Education System in Times of Crisis: Empirical Findings, Consequences and Potential for Teaching and Learning], 1st ed.; Reintjes, C., Porsch, R., im Brahm, G., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2021; pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- SAP America. Qualtrics Survey (Online Survey Software). Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. The five-factor model of personality and its relevance to personality disorders. J. Pers. Disord. 1992, 6, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Raad, B. The Big Five Personality Factors: The Psycholexical Approach to Personality, 1st ed.; Hogrefe & Huber: Ashland, OH, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0889372368. [Google Scholar]

- John, O.P.; Naumann, L.P.; Soto, C.J. Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 3rd ed.; John, O.P., Robins, R.W., Pervin, L.A., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 114–158. [Google Scholar]

- Roccas, S.; Sagiv, L.; Schwartz, S.H.; Knafo, A. The Big Five Personality Factors and Personal Values. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkenau, P.; Ostendorf, F. NEO-Fünf-Faktoren-Inventar nach Costa und McCrae [NEO Five-Factor Inventory According to Costa and McCrae], 2nd ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Körner, A.; Geyer, M.; Brähler, E. Das NEO-Fünf-Faktoren Inventar (NEO-FFI) [The NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI)]. Diagnostica 2002, 48, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M.; Gollwitzer, M.; Schmitt, M. Statistik und Forschungsmethoden [Statistics and Research Methods], 5th ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3621282017. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Locke, E.A.; Durham, C.C.; Kluger, A.N. Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, T.A.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.E.; Thoresen, C.J. The Core Self-Evaluations Scale: Development of a measure. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpp, T.; Muck, P.M.; Hülsheger, U.R.; Judge, T.A.; Maier, G.W. Core self-evaluations in Germany: Validation of a German measure and its relationships with career success. Appl. Psychol.-Int. Rev. 2010, 59, 674–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.E.; Thoresen, C.J. Are measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of control, and generalized self-efficacy indicators of a common core construct? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyer, F.J.; Asendorpf, J.B. Psychologie der Persönlichkeit [Psychology of Personality], 6th ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3662549414. [Google Scholar]

- Rauthmann, J.F. Persönlichkeitspsychologie: Paradigmen—Strömungen—Theorien [Personality Psychology: Paradigms—Trends—Theories], 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3662530030. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Bono, J.E.; Erez, A.; Locke, E.A. Core Self-Evaluations and Job and Life Satisfaction: The Role of Self-Concordance and Goal Attainment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- König, J.; Jäger-Biela, D.J.; Glutsch, N. Adapting to online teaching during COVID-19 school closure: Teacher education and teacher competence effects among early career teachers in Germany. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrinos, H.A.; Donnelly, R.P. Learning Loss during COVID-19: An Early Systematic Review. Res. Sq. 2021. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikali, K. The dangers of social distancing: How COVID-19 can reshape our social experience. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 2435–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Kuyper, H.; Seaton, M.; Parker, P.D.; Morin, A.J.S.; Möller, J.; Abduljabbar, A.S. Dimensional comparison theory: An extension of the internal/external frame of reference effect on academic self-concept formation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, W.-U. Das Konzept von der eigenen Begabung: Auswirkungen, Stabilität und vorauslaufende Bedingungen [The concept of one’s own ability: Effects, stability and antecedents]. Psychol. Rundsch. 1984, 35, 136–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rheinberg, F. Bezugsnormen und schulische Leistungsbeurteilung [Reference standards and performance assessment in school]. In Leistungsmessungen in Schulen [Performance Assessments in Schools], 3rd ed.; Weinert, F.E., Ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2014; pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tesser, A. Toward a self-evaluation maintenance model of social behavior. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Social psychological studies of the self: Perspectives and programs; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1988; Volume 21, pp. 181–227. [Google Scholar]

- Elsholz, M. Das Akademische Selbstkonzept Angehender Physiklehrkräfte als Teil Ihrer Professionellen Identität: Dimensionalität und Veränderung Während Einer Zentralen Praxisphase [The Academic Self-Concept of Aspiring Physics Teachers a Spart of Their Professional Identity: Dimensionality and Development during a Central Phase of Practical Involvement], 1st ed.; Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3832548575. [Google Scholar]

- De Raad, B.; Schouwenburg, H.C. Personality in learning and education: A review. Eur. J. Pers. 1996, 10, 303–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatzka, T. Aspects of openness as predictors of academic achievement. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021, 170, 110422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, J.; Ones, D.S. Conscientiousness and integrity at work. In Handbook of Personality Psychology, 1st ed.; Hogan, R., Johnson, J., Briggs, S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 849–870. [Google Scholar]

- John, R.; John, R.; Rao, Z.-R. The Big Five Personality Traits and Academic Performance. J. Law Soc. Stud. 2020, 2, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammadov, S. Big Five personality traits and academic performance: A meta-analysis. J. Pers. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.C.; Paunonen, S.V. Big Five personality predictors of post-secondary academic performance. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2007, 43, 971–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapmann, S.; Hell, B.; Hirn, J.-O.W.; Schuler, H. Meta-analysis of the relationship between the Big Five and academic success at university. Z Psychol. 2007, 215, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cook, C.T. Is Adaptability of Personality a Trait? Ph.D. Thesis, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lauret, D.; Bayram-Jacobs, D. COVID-19 Lockdown Education: The Importance of Structure in a Suddenly Changed Learning Environment. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limniou, M.; Varga-Atkins, T.; Hands, C.; Elshamaa, M. Learning, Student Digital Capabilities and Academic Performance over the COVID-19 Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, C.; Hegde, S.; Smith, A.; Wang, X.; Sasangohar, F. Effects of COVID-19 on College Students’ Mental Health in the United States: Interview Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A.; Palazzeschi, L. Core Self-Evaluation. In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Carducci, B.J., Nave, C.S., Fabio, A., Saklofske, D.H., Stough, C., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; Volume III, pp. 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.E. The power of being positive: The relation between positive self-concept and job performance. Hum. Perform 1998, 11, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, L.; Cervone, D.; Sharpe, B.T. Goals and Self-Efficacy Beliefs during the Initial COVID-19 Lockdown: A Mixed Methods Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 559114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H. Exploring the association between compliance with measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and big five traits with Bayesian generalized linear model. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021, 176, 110787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lörz, M.; Zimmer, L.M.; Koopmann, J. Herausforderungen und Konsequenzen der Corona-Pandemie für Studierende in Deutschland [Challenges and consequences of the corona pandemic for university students in Germany]. Psychol. Erz. Unterr. 2021, 4, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. FAQ: Humanities and Social Sciences. Available online: https://www.dfg.de/foerderung/faq/geistes_sozialwissenschaften/index.html (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- World Medical Association. WMA’s Declaration of Helsinki Serves as Guide to Physicians. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1964, 189, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petousi, V.; Sifaki, E. Contextualising harm in the framework of research misconduct. Findings from discourse analysis of scientific publications. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 23, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, 59, 294. [Google Scholar]

| Dimensions of Self-Concept of Professional Knowledge | Style of Learning | n | M1 | SD | t-Test | dCohen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TK | on-site | 201 | 4.28 | 1.21 | t(386.25) = 0.29 | |

| distance | 194 | 4.31 | 1.03 | |||

| CK | on-site | 201 | 4.63 | 0.82 | t(393) = 2.27 * | 0.23 |

| distance | 194 | 4.43 | 0.93 | |||

| PK | on-site | 201 | 5.19 | 0.85 | t(393) = 3.10 ** | 0.31 |

| distance | 194 | 4.93 | 0.83 | |||

| PCK | on-site | 201 | 4.99 | 0.90 | t(355.49) = 5.44 *** | 0.55 |

| distance | 194 | 4.40 | 1.21 | |||

| TCK | on-site | 201 | 4.56 | 1.16 | t(379.08) = 5.25 *** | 0.53 |

| distance | 194 | 3.90 | 1.35 | |||

| TPK | on-site | 201 | 5.01 | 0.90 | t(393) = 3.62 *** | 0.36 |

| distance | 194 | 4.66 | 1.01 | |||

| TPCK | on-site | 201 | 4.78 | 1.00 | t(363.82) = 4.83 *** | 0.49 |

| distance | 194 | 4.21 | 1.30 |

| Big Five Dimensions | Style of Learning | n | M1 | SD | t-Test | dCohen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | on-site | 201 | 20.42 | 7.62 | t(393) = 1.65 | |

| distance | 194 | 21.69 | 7.98 | |||

| Extraversion | on-site | 201 | 29.79 | 5.80 | t(384.91) = 0.45 | |

| distance | 194 | 30.09 | 6.48 | |||

| Openness to experience | on-site | 201 | 28.62 | 5.85 | t(392) = 4.41 *** | 0.44 |

| distance | 194 | 31.13 | 5.43 | |||

| Agreeableness | on-site | 201 | 34.04 | 5.65 | t(393) = 2.64 ** | 0.27 |

| distance | 194 | 35.55 | 5.61 | |||

| Conscientiousness | on-site | 201 | 32.63 | 6.13 | t(393) = 3.23 ** | 0.33 |

| distance | 194 | 34.68 | 6.19 |

| Aspects Relating to Successful Teaching and Learning | Absolute Rating 1 | Compared to On-Site Learning 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Motivation of the learners to continuously deal with a topic | 2.23 | 0.81 | −0.38 | 0.76 |

| Interaction with other students on learning contents | 2.24 | 1.04 | −0.44 | 0.77 |

| Monitoring of the learners’ individual learning progress | 2.29 | 0.87 | −0.37 | 0.66 |

| Communication of realistic learning goals | 2.32 | 0.84 | −0.38 | 0.68 |

| Extent of the learning content 3 | 2.32 | 0.88 | −0.61 | 0.62 |

| Encouragement of the learners to reflect on individual learning progress | 2.36 | 0.85 | −0.30 | 0.71 |

| Encouragement of the learners to participate actively in courses | 2.39 | 0.85 | −0.39 | 0.76 |

| Structuring and portioning of the learning content | 2.39 | 0.89 | −0.44 | 0.68 |

| Communication of learning contents’ practical relevance and usefulness | 2.51 | 0.89 | −0.31 | 0.60 |

| Support of the learners in case of comprehension difficulties | 2.51 | 0.94 | −0.29 | 0.74 |

| Level of complexity of the learning content | 2.63 | 0.77 | −0.30 | 0.62 |

| Consideration of the learners’ prior knowledge and experiences | 2.63 | 0.82 | −0.26 | 0.54 |

| Fit between teaching formats used and learning objectives | 2.64 | 0.69 | −0.40 | 0.71 |

| Promotion of learning progress (knowledge, interest, practical skills) | 2.65 | 0.77 | −0.25 | 0.67 |

| Reply to learners’ content-related questions | 2.76 | 0.90 | −0.23 | 0.72 |

| Communication of organizational aspects (e.g., planned time flow) | 2.77 | 0.94 | −0.26 | 0.70 |

| Reply to learners’ organizational matters | 2.85 | 0.87 | −0.27 | 0.63 |

| Aspects Relating to the Attitude Towards Digital Teaching and Learning | M1 | SD |

|---|---|---|

| The integration of e-learning elements reduces the students’ effort in the long term. | 3.55 | 3.40 |

| E-learning enables a better handling of heterogeneous groups of learners. | 4.21 | 3.26 |

| The use of e-learning has more advantages than disadvantages. | 4.79 | 3.28 |

| In the future, I would like to use more e-learning in my university studies. | 5.14 | 3.71 |

| The use of e-learning overall enriched my university studies. | 5.14 | 3.37 |

| The integration of e-learning elements reduces the lecturers’ effort in the long term. | 5.42 | 2.97 |

| A targeted integration of e-learning can offer scopes for on-site learning and more personal support for every student. | 5.60 | 3.35 |

| I am happy with the opportunity to use e-learning in my university studies. | 6.93 | 2.96 |

| E-learning enables students to learn more flexibly. | 7.04 | 3.30 |

| Technical Conditions of Digital Teaching and Learning | M1 | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibility of courses (e.g., for disabled students) | 1.87 | 1.12 |

| Technical support | 2.70 | 1.14 |

| Effort to come to terms with | 3.13 | 1.17 |

| Usability (navigation, clear arrangement, etc.) | 3.44 | 1.13 |

| Available hardware equipment (PC, laptop, DSL router, microphone, etc.) | 3.71 | 1.15 |

| Available software equipment (e-learning platforms, video software, audio software, etc.) | 3.73 | 0.92 |

| Digital Skills | M1 | SD |

|---|---|---|

| I can describe and comply with legal regulations (copyright, license agreements, etc.) when using digital information. | 2.27 | 0.92 |

| I can describe quality characteristics for rating digital information. | 2.64 | 0.83 |

| I can take measures to protect my digital data. | 2.65 | 0.86 |

| I feel able to advise or guide other students in the use of e-learning. | 2.85 | 0.74 |

| I critically reflect on my own usage behavior of digital media (media types and content, duration, and locations, etc.). | 2.99 | 0.77 |

| I can describe forms of online cooperation. | 3.04 | 0.69 |

| I can edit videos and images. | 3.07 | 0.92 |

| I know digital sources for researching expert information. | 3.10 | 0.79 |

| I can manage files digitally (e.g., using network drives or cloud storage). | 3.11 | 0.79 |

| I can describe several functions of typical Web 2.0 tools (e.g., social networks, blogs, wikis, forums). | 3.12 | 0.65 |

| I can identify potential problems and opportunities in online communication. | 3.15 | 0.63 |

| I can use MS Office applications (word processing, spreadsheets, presentations, etc.). | 3.60 | 0.54 |

| I can use e-learning platforms related to my courses (e.g., join a forum discussion, download materials, upload files, contact other students). | 3.80 | 0.40 |

| Handicaps 1,2 | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Increased psychological stress | 49 | 58 |

| Financial problems | 24 | 29 |

| Technical problems when using e-learning | 21 | 25 |

| Childcare | 12 | 14 |

| Care for relatives | 7 | 8 |

| Severely at risk of COVID-19 | 5 | 6 |

| Quarantine order | 5 | 6 |

| Chronic illness or disability | 2 | 2 |

| Infection with COVID-19 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 9 | 11 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Aspects relating to successful teaching and learning | — | |||||

| 2 Technical conditions | 0.40 *** | — | ||||

| 3 Digital skills | 0.17 | 0.07 | — | |||

| 4 Attitude towards digital teaching and learning | 0.66 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.17 | — | ||

| 5 Number of handicaps 1 | −0.38 *** | −0.38 *** | −0.19 | −0.39 *** | — | |

| 6 Core self-evaluations | 0.32 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.43 *** | 0.25 * | −0.35 ** | — |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Emmerichs, L.; Welter, V.D.E.; Schlüter, K. University Teacher Students’ Learning in Times of COVID-19. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120776

Emmerichs L, Welter VDE, Schlüter K. University Teacher Students’ Learning in Times of COVID-19. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(12):776. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120776

Chicago/Turabian StyleEmmerichs, Lars, Virginia Deborah Elaine Welter, and Kirsten Schlüter. 2021. "University Teacher Students’ Learning in Times of COVID-19" Education Sciences 11, no. 12: 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120776

APA StyleEmmerichs, L., Welter, V. D. E., & Schlüter, K. (2021). University Teacher Students’ Learning in Times of COVID-19. Education Sciences, 11(12), 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120776