Effects of an Interdisciplinary Course on Pre-Service Primary Teachers’ Content Knowledge and Academic Self-Concepts in Science and Technology–A Quantitative Longitudinal Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Teacher generalist training and teaching-out-of-field: In many countries, primary teachers are educated as generalists who have to teach multiple subjects [29,40,41]. However, training in three to four or more subjects also implies fewer contact hours per subject [42,43,44,45]. This is problematic for the goal of increasing CK and ASCs—positively correlating with the corresponding CK domain (see Section 1.2)—, as it has been shown that the number of contact hours with the subject at the university correlates positively with the level of CK [46]. Primary teachers who took a science major during their studies have a higher science CK than primary teachers without this major [22,45]. In some countries, such as China [7] or Germany [47], science and technology are sometimes not covered at all during studies [43,44,45]. Nevertheless, primary school teachers then have to teach topics from these disciplines in their role as classroom teachers [48].

- Subject-integrated teaching—broad study content: With the aim of exploring the multi-perspective world (see above), in many countries, including Japan, France, Austria, The Netherlands, Slovenia, China and Germany, science and technology content is taught within an integrated subject in primary school [7,45,49,50]. By the term “integrative” we mean that the subject includes not only biology, chemistry, physics and (sometimes) technology, but also disciplines such as history, social sciences, geography [7,45,49,50,51]. Since this subject is called differently in each country [45], the term “General Studies” (Sachunterricht) is used as a generalization in the following. This is the term used in Germany [3], where this study was conducted. Thus, at best, primary teachers should have CK and positive ASCs in all of these disciplines (hereafter used synonymously with the term “domain”; [13,51]). Given the interdisciplinary nature of this subject, primary teachers should at the same time be able to think across disciplines and appropriately connect the content of different fields [13].

1.1. Teachers’ Content Knowledge: Definition, Structure, Relevance, Operationalization and Influencing Factors

1.2. Teachers’ Academic Self-Concept: Definition, Structure, Operationalization, Relevance and Influencing Factors

1.3. Research on the Development of Pre- and In-Service Primary Teachers Science- and Technolgy-Related CK and ASCs through Interdisciplinary Interventions: Status Quo and Research Gaps

1.4. Research on the Development of Pre- and In-Service Teachers CK and ASCs through Different Course Formats: Status Quo and Research Gaps

1.5. Aim of the Study

- RQ 1: The intervention’s impact on CK and ASC in science and technology

- RQ 1.1: Does participation in the intervention lead to short-term and long-term gains in CK in science and technology compared to non-participation?

- RQ 1.2: Does participation in the intervention lead to a change in biology-, chemistry-, physics- and technology-related ASCs compared to non-participation?

- RQ 2: Correlations between cognitive gain and changes in ASCs

- RQ 3: Impact of the course format

- RQ 3.1: Are there equivalent short- and long-term cognitive gains between pre-service teachers attending a traditional/weekly and an intensive/block course format of the intervention?

- RQ 3.2: Does the course format impact the development of biology-, chemistry-, physics- and technology-related ASCs?

- RQ 4: Impact of the major field of study

- RQ 4.1: Does the major field of study affect short- and long-term cognitive gains within groups of weekly and block course participants?

- RQ 4.2: Does the major field of studies influence the development of biology-, chemistry-, physics- and technology-related ASCs within groups of weekly and block course participants?

2. Materials and Methods

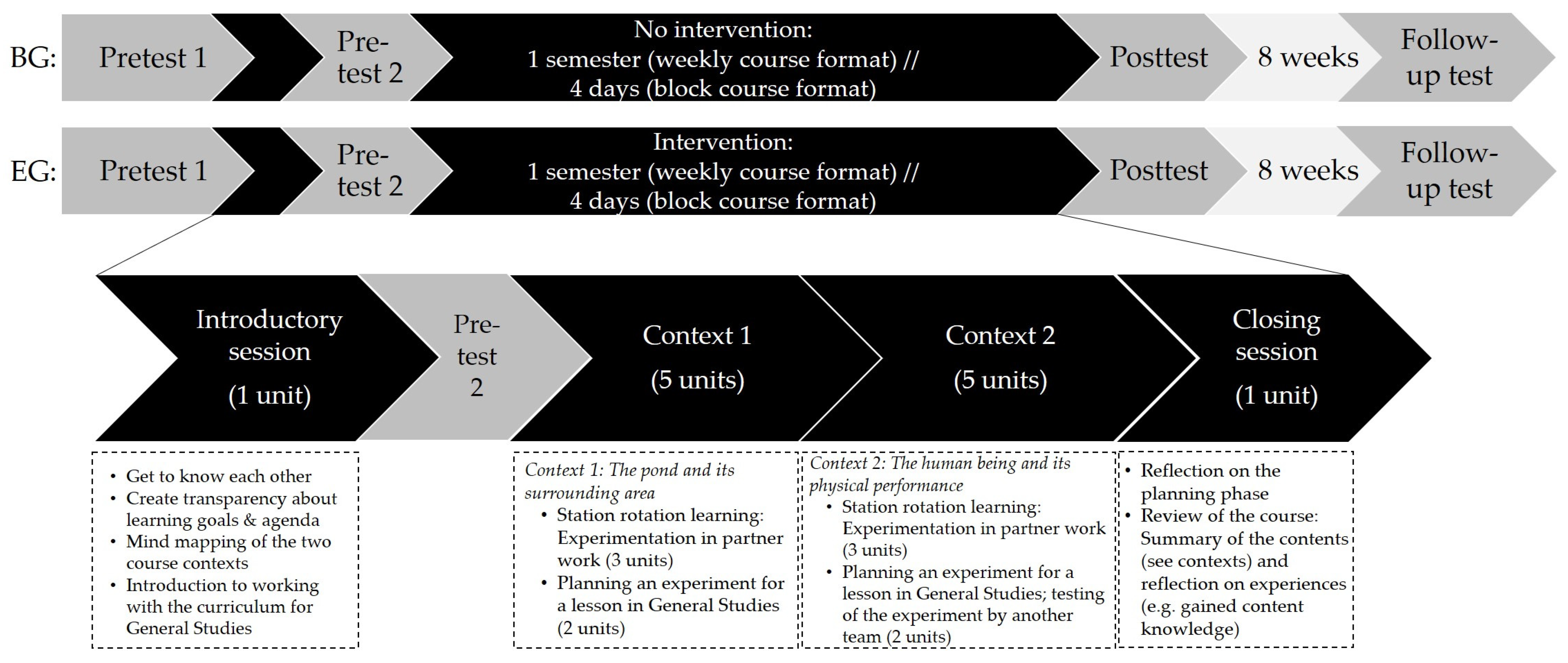

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Summary of the Intervention’s Educational Concept and the Curricular Framework

- Before conducting the experiments: In the introductory session, the participants create a mind map for each of the two contexts noting existing CK on the subjects biology, chemistry, physics and technology. The creation and subsequent review of all mind maps prepared in partner work not only serve to activate prior knowledge but also help to recognize first contextual relationships and get an overview of the course topics [175]. Based on the mind maps’ contents, the lecturer finally resolves which of the mentioned contents will be covered in the course.

- When conducting the experiments: Questions such as “What makes water lilies float on the surface of the water?” and “Why does a small stone sink?” form the starting point of the experimentation process. Considering that most pre-service primary teachers are more interested in biology than the other three subjects [176,177], many of the questions were formulated from a biological perspective to reduce the reservations many primary teachers have about the subjects of chemistry, physics and technology (see Section 1). The station worksheets are designed to develop biological, chemical, physical and technical CK through experimentation. First, hypotheses can be made about the outcome of the experiments. By conducting and interpreting experiments and accompanied by sharing ideas with the team partner, these hypotheses are verified or falsified. Thus, conceptual change [178] is enabled. During this work process, the participants should become aware that there is no division into individual subjects in nature, that many biological or technical phenomena can only be explained by chemical and physical laws and that chemistry [120], physics and technology have high relevance for everyday life [179,180].

- After conducting the experiments:

- a.

- Background information: For each station a one-page text with further information on the scientific background of the experiment is available. This can be read as a refresher or reinforcement of CK if there is time after the station is completed and before the plenary debrief (see 3b). After each session, digital versions are available in the digital learning room, also containing bibliographical references to simplify further engagement into the topics.

- b.

- Debrief: After each experimental work phase and in the final session, CK gained and interdisciplinary connections experienced are brought together and discussed in the plenary. This debrief is guided by the lecturer, supported by presentation slides with pictures from the experimentation phase and by giving impulses [175].

- c.

- Applying CK: In two additional units per topic block (see Figure 1), participants practice planning experiment-based science/technology lessons by applying and combining CK and PCK to create a child-oriented experiment. In doing so, they can realize that CK is important for the development of PCK [69,70,71]. As part of this planning, CK that the teacher will need for this experiment is recorded in bullet points on a poster. The lecturer then provides written feedback to the groups on their planning via the digital learning space. Participants have access to feedback for all groups but do not know which people are behind which planning product to avoid social comparisons [112].

2.3. Sample

2.4. Instruments and Data Collection

2.4.1. Cognitive Test

2.4.2. Affective Questionnaire

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Impact of the Intervention: Comparison of EG and BG

3.1.1. Content Knowledge (RQ 1.1)

3.1.2. Academic Self-Concepts (RQ 1.2)

3.2. Correlations between Cognitive Gain and Changes in ASCs (RQ 2)

3.3. Impact of the Course Format

3.3.1. Content Knowledge (RQ 3.1)

3.3.2. Academic Self-Concepts (RQ 3.2)

3.4. Impact of the Major Field of Study

3.4.1. Content Knowledge (RQ 4.1)

3.4.2. Academic Self-Concepts (RQ 4.2)

4. Discussion

4.1. The Intervention’s Impact on Pre-Service Primary Teachers’ CK and ASCs

4.1.1. Cognitive Gain

4.1.2. Science- and Technology-Related Academic Self-Concepts

4.2. Impact of the Course Format

4.3. Impact of the Major Field of Study

4.4. Limitations and Implications for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Topic (Subtopic) | Content Level | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bionics (Lotus effect) | primary school | [217,218] |

| secondary school | [219,220] | |

| university | [221,222,223,224] | |

| The human body (air and respiratory system) | primary school | [225,226,227,228,229] |

| secondary school | [230,231,232] | |

| university | [233,234,235,236] |

| Original Question with Corresponding Items | Translation of Sample Question with Corresponding Items | Type of Question | Disciplines | Content Level | Complexity Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Es geht nun um die Phasenübergänge zwischen den Aggregatzuständen fest, flüssig und gasförmig. Geben Sie die Bezeichnung (ein Wort genügt, z.B. “Schmelzen”) für die genannten Vorgänge an. Falls Sie es nicht wissen, setzen Sie ein Fragezeichen (?).

| It is now about the phase transitions between the physical states of matter (solid, liquid, and gas). Enter the term (one word is sufficient, e.g., “melting”) for the processes mentioned. If you don’t know, put a question mark (?).

| open-ended question | chemistry, physics | primary school, secondary school (solid to gas: secondary school, university level) | fact |

Welche dieser Geräte gehören zu den zweiseitigen Hebeln? Kreuzen Sie alles Zutreffende an!

| Which of these devices belong to the two-sided levers? Tick all that apply!

| closed-ended question | physics, technology | secondary school | relations/concepts |

Beim Blutdruckmessen einer Ihnen unbekannten Person zeigt Ihr Blutdruckmessgerät folgende Werte an: Blutdruck: 90/60. Welche dieser Aussagen sind dann korrekt?

| When measuring the blood pressure of a person you do not know, your blood pressure monitor shows the following values: Blood pressure: 90/60. Which of these statements are correct?

| closed-ended question | biology, physics | secondary school, university | relations/concepts |

| Item Abbreviation (Pre/Post) | Factor 1 (Pre/Post) | Factor 2 (Pre/Post) | Factor 3 (Pre/Post) | Factor 4 (Pre/Post) | h2 (Pre/Post) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TU31_03/NT19_11 | 0.689/0.781 | - | - | - | 0.490/0.640 |

| TU31_05/NT19_01 | 0.875/0.896 | - | - | - | 0.794/0.827 |

| TU31_08/NT19_06 | 0.832/0.754 | - | - | - | 0.715/0.598 |

| TU31_06/NT19_05 | - | 0.878/0.877 | - | - | 0.792/0.808 |

| TU31_11/NT19_10 | - | 0.910/0.910 | - | - | 0.864/0.873 |

| TU31_13/NT19_12 | - | 0.887/0.820 | - | - | 0.837/0.736 |

| TU31_09/NT19_18 | - | - | 0.846/0.877 | -/0.328 | 0.784/0.894 |

| TU31_14/NT19_15 | - | - | 0.836/0.856 | - | 0.803/0.817 |

| TU31_16/NT19_08 | - | - | 0.876/0.808 | -/0.305 | 0.844/0.760 |

| TU31_02/NT19_04 | - | - | - | 0.805/0.896 | 0.735/0.913 |

| TU31_15/NT19_14 | - | - | 0.342/0.361 | 0.716/0.754 | 0.641/0.711 |

| TU31_17/NT19_17 | - | - | -/0.373 | 0.755/0.680 | 0.705/0.649 |

References

- Bybee, R.W. Achieving Scientific Literacy. Sci. Teach. 1995, 62, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mammes, I.; Schaper, N.; Strobel, J. Professionalism and the Role of Teacher Beliefs in Technology Teaching in German Primary Schools—An Area of Conflict. In Teachers’ Pedagogical Beliefs: Definition and Operationalisation—Connections to Knowledge and Performance—Development and Change; König, J., Ed.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2012; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gesellschaft für Didaktik des Sachunterrichts (GDSU). Perspektivrahmen Sachunterricht; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. A Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- van den Akker, J.J.H. The Science Curriculum: Between Ideals and Outcomes. In International Handbook of Science Education; Fraser, B.J., Tobin, K.G., Eds.; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 421–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skolverket Sweden. Curriculum for the Compulsory School, Preschool Class and School-Age Educare 2001, Revised 2018. Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/getFile?file=3984 (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Zhengmei, P.; Shaoyang, W. Der Sachunterrichtslehrplan der chinesischen Grundschule. In Handbuch Didaktik des Sachunterrichts, 2nd ed.; Kahlert, J., Fölling-Albers, M., Götz, M., Hartinger, A., Miller, S., Wittkowske, S., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2015; pp. 304–309. [Google Scholar]

- Lange-Schubert, K.; Hartinger, A. Lehrerkompetenzen im Sachunterricht. In Sachunterricht—Didaktik für die Grundschule, 5th ed.; Hartinger, A., Lange-Schubert, K., Eds.; Cornelsen: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L.S. Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching. Educ. Res. 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1987, 57, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumert, J.; Kunter, M. The COACTIV Model of Teachers’ Professional Competence. In Cognitive Activation in the Mathematics Classroom and Professional Competence of Teachers: Results from the COACTIV Project; Kunter, M., Baumert, J., Blum, W., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., Neubrand, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, T.; Brouwer, W. Teacher awareness of student alternate conceptions about rotational motion and gravity. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1991, 28, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesellschaft für Didaktik des Sachunterrichts (GDSU). Qualitätsrahmen Lehrerbildung—Sachunterricht und Seine Didaktik; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Blömeke, S.; Gustaffson, J.-E.; Shavelson, R.J. Beyond Dichotomies: Competence Viewed as a Continuum. Z. Psychol. 2015, 223, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautwein, U.; Möller, J. Self-Concept: Determinants and Consequences of Academic Self-Concept in School Contexts. In Psychosocial Skills and School Systems in the 21st Century. Theory, Research, and Practice; Lipnevich, A.A., Preckel, F., Roberts, R.D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickhäuser, O. Fähigkeitsselbstkonzepte—Entstehung, Auswirkung, Förderung. Z. Padagog. Psychol. 2006, 20, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleickmann, T. Professionelle Kompetenz von Primarschullehrkräften im Bereich des naturwissenschaftlichen Sachunterrichts. Z. Grund. 2015, 8, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Landwehr, B. Distanzen von Lehrkräften und Studierenden des Sachunterrichts zur Physik. In Eine Qualitativ-Empirische Studie zu den Ursachen; Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Köster, H.; von Balluseck, H.; Kraner, R. Technische Bildung im Elementar—und Primarbereich. In Technische Bildung für Alle: Ein vernachlässigtes Schlüsselelement der Innovationspolitik; Buhr, R., Hartmann, E.A., Eds.; VDI/VDE Innovation + Technik GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, K. Naturwissenschaftliches Lernen in der Grundschule—Welche Kompetenzen brauchen Grundschullehrkräfte? In Lehrerbildung: IGLU und die Folgen; Merkens, H., Ed.; Leske + Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 2004; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, A.S.; Craven, R.G.; Kaur, G. Teachers’ self-concept and valuing of learning: Relations with teaching approaches and beliefs about students. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2014, 42, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlen, W. Primary Teachers’ Understanding in Science and its Impact in the Classroom. Res. Sci. Educ. 1997, 27, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, C.; Summers, M. Primary School Teachers’ Understanding of Science Concepts. J. Educ. Teach. 1988, 14, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.; Smith, G. The impact of a curriculum course on pre-service primary teachers’ science content knowledge and attitudes towards teaching science. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2012, 31, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Senocak, E. Prospective Primary School Teachers’ Perceptions on Boiling and Freezing. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2009, 34, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, D.C.; Neale, D.C. The construction of subject matter knowledge in primary science teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1989, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.; Wenner, G. Elementary Preservice Teachers’ Knowledge and Beliefs Regarding Science and Mathematics. Sch. Sci. Math. 1996, 96, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban-Woldron, H. Fachwissen—ein wichtiger Bestandteil des Professionswissens von Volksschullehrkräften? Eine empirische Studie zu einer Lehrveranstaltung im naturwissenschaftlichen Sachunterricht. R.E.-SOURCE 2014, 1, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, K. Elementary Science Teaching. In Handbook of Research on Science Education; Abell, S.K., Lederman, N.G., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 493–535. [Google Scholar]

- Fleer, M. Early Childhood Science Teacher Education. In Encyclopedia of Science Education; Gunstone, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mant, J.; Summers, M. Some primary school teachers’ understanding of the earth’s place in the universe. Res. Pap. Educ. 1993, 8, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göhring, A. Naturwissenschaftlich integrierte Lehrerbildung an der Universität—Modellversuch Naturwissenschaft und Technik (NWT). In Vielperspektivität im Sachunterricht; Giest, H., Hartinger, A., Tänzer, S., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2017; pp. 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl, A. Unterrichten von Natur und Technik in Kindergarten und Primarschule: Zu den Vorlieben von Lehramtsstudierenden. In Naturwissenschaftliche Kompetenzen in der Gesellschaft von Morgen, Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Society for the Principles of Teaching Chemistry and Physics (GDCP), Wien, Australia, 9 September 2019; Habig, S., Ed.; University of Duisburg-Essen: Duisburg/Essen, Germany, 2020; pp. 625–628. [Google Scholar]

- Book, C.L.; Freeman, D.J. Differences in Entry Characteristics of Elementary and Secondary Teacher Candidates. J. Teach. Educ. 1986, 37, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billich-Knapp, M.; Künstig, J.; Lipowsky, F. Profile der Studienwahlmotivation bei Grundschullehramtsstudierenden. Z. Pädagogik 2012, 58, 696–719. [Google Scholar]

- König, J.; Rothland, M.; Darge, K.; Lünnemann, M.; Tachtsoglou, S. Erfassung und Struktur berufswahlrelevanter Faktoren für die Lehrerausbildung und den Lehrerberuf in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. Z. Erzieh. 2013, 16, 553–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojer, P. Wer Wird Lehrer/Lehrerin? Konzepte der Berufswahl und Befunde zur Entwicklung des Berufswunsches Lehrer/in und ihre Bedeutung für das Studium; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weiß, S.; Braune, A.; Steinherr, E.; Kiel, E. Studium Grundschullehramt. Zur problematischen Kompatibilität von Studien-/Berufswahlmotiven und Berufsvorstellungen. Z. Grund. 2009, 2, 126–138. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Yeung, A.S. Coursework selection: Relations to academic self-concept and achievement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1997, 34, 691–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.A.; Petish, D.; Smithey, J. Challenges New Science Teachers Face. Rev. Educ. Res. 2006, 76, 607–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döhrmann, M.; Hacke, S.; Buchholz, C. Nationale und internationale Typen an Ausbildungsgängen zur Primarstufenlehrkraft. In TEDS-M 2008. Professionelle Kompetenz und Lerngelegenheiten Angehender Primarstufenlehrkräfte im Internationalen Vergleich; Blömeke, S., Kaiser, G., Lehmann, R., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2010; pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Blömeke, S.; Kaiser, G.; Lehmann, R. TEDS-M 2008 Primarstufe: Ziele, Untersuchungsanlage und zentrale Ergebnisse. In TEDS-M 2008. Professionelle Kompetenz und Lerngelegenheiten Angehender Primarstufenlehrkräfte im Internationalen Vergleich; Blömeke, S., Kaiser, G., Lehmann, R., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2010; pp. 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, Y.; Beudels, M.; Kuckuck, M.; Preisfeld, A. Sachunterrichtsbezogene Teilstudiengänge aus NRW auf dem Prüfstand. Eine Dokumentenanalyse der Bachelor—und Masterprüfungsordnungen. HLZ 2021, 4, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgardt, I.; Kaiser, A. Lehrer—und Lehrerinnenbildung. In Handbuch Didaktik des Sachunterrichts, 2nd ed.; Kahlert, J., Fölling-Albers, M., Götz, M., Hartinger, A., Miller, S., Wittkowske, S., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2015; pp. 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, M. Professionswissen von Sachunterrichtslehrkräften: Zusammenhangsanalyse zur Wirkung von Ausbildungshintergrund und Unterrichtserfahrung Auf das fachspezifische Professionswissen im Unterrichtsinhalt “Verbrennung”; Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Riese, J.; Reinhold, R. Fachbezogene Kompetenzmessung und Kompetenzentwicklung bei Lehramtsstudierenden der Physik im Vergleich verschiedener Studiengänge. Lehr. Prüfstand 2009, 2, 104–125. [Google Scholar]

- Porsch, R. Fachfremdes Unterrichten in Deutschland: Welche Rolle spielt die Lehrerbildung? In Professionelles Handeln im Fachfremd Erteilten Mathematikunterricht; Porsch, R., Rösken.Winter, B., Eds.; Springer Spektrum: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsch, R.; Wendt, H. Aus- und Fortbildung von Mathematik—und Sachunterrichtslehrkräften. In TIMSS 2015. Mathematische und Naturwissenschaftliche Kompetenzen von Grundschulkindern in Deutschland im Internationalen Vergleich; Wendt, H., Bos, W., Selter, C., Köller, O., Schwippert, K., Kasper, D., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Harada, N. Lebenskundeunterricht als integrativ-anschlussfähiges Schulfach Japans. In Handbuch Didaktik des Sachunterrichts, 2nd ed.; Kahlert, J., Fölling-Albers, M., Götz, M., Hartinger, A., Miller, S., Wittkowske, S., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2015; pp. 289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, M. Sachunterricht in Frankreich. In Handbuch Didaktik des Sachunterrichts, 2nd ed.; Kahlert, J., Fölling-Albers, M., Götz, M., Hartinger, A., Miller, S., Wittkowske, S., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2015; pp. 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Meschede, N.; Hartinger, A.; Möller, K. Sachunterricht in der Lehrerinnen—und Lehrerbildung. Rahmenbedingungen, Befunde und Perspektiven. In Handbuch Lehrerinnen—und Lehrerbildung; Cramer, C., König, J., Rothland, M., Blömeke, S., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2020; pp. 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, K.; Kleickmann, T.; Lange-Schubert, K.; Todorova, M. Professionelle Kompetenz für den naturwissenschaftlichen Sachunterricht—ihre Bedeutung für Unterrichtsqualität und Möglichkeiten ihrer Förderung. In Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften der Chemie und Physik; Fischler, H., Sumfleth, E., Eds.; Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 157–183. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann, P.L. The Making of a Teacher: Teacher Knowledge and Teacher Education; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Artelt, C.; Kunter, M. Kompetenzen und berufliche Entwicklung von Lehrkräften. In Psychologie für den Lehrberuf; Urhahne, D., Dresel, M., Fischer, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumert, J.; Kunter, M.; Blum, W.; Brunner, M.; Voss, T.; Jordan, A.; Klusmann, U.; Krauss, S.; Neubrand, M.; Tsai, Y.-M. Teachers’ Mathematical Knowledge, Cognitive Activation in the Classroom, and Student Progress. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 47, 133–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grossman, P.L.; Schoenfeld, A.H.; Lee, C. Teaching subject matter. In Preparing Teachers for a Changing World: What Teachers Should Learn and Be Able to Do; Darling-Hammond, L., Bransford, J.D., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 201–231. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, D.L.; Thames, M.H.; Phelps, G. Content Knowledge for Teaching: What Makes It Special? J. Teach. Educ. 2008, 59, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hashweh, M.Z. Effects of subject-matter knowledge in the teaching of biology and physics. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1987, 3, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, J.J. Science, Curriculum, and Liberal Education: Selected Essays; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Abell, S.K. Research on science teacher knowledge. In Handbook of Research on Science Education; Abell, S.K., Lederman, N.G., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 1105–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, P.L.; Wilson, S.M.; Shulman, L.S. Teachers of substance: Subject matter knowledge for teaching. In Knowledge Base for the Beginning Teacher; Reynolds, M.C., Ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1989; pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-El-Khalick, F.; BouJaoude, S. An exploratory study of the knowledge base for science teaching. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1997, 34, 673–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.W.; Krathwohl, D.R. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing. A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, S.G.; Lipson, M.Y.; Wixson, K.K. Becoming a strategic reader. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 1983, 8, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavelson, R.J.; Ruiz-Primo, M.A.; Wiley, E.W. Windows into the mind. High. Educ. 2005, 49, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capraro, R.; Capraro, M.; Parker, D.; Kulm, G.; Raulerson, T. The Mathematics Content Knowledge Role in Developing Preservice Teachers’ Pedagogical Content Knowledge. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2005, 20, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depaepe, F.; Torbeyns, J.; Vermeersch, N.; Janssens, D.; Janssen, R.; Kelchtermans, G.; Verschaffel, L.; Dooren, W.V. Teachers’ content and pedagogical content knowledge on rational numbers: A comparison of prospective elementary and lower secondary school teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 47, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käpylä, M.; Heikkinen, J.-P.; Asunta, T. Influence of Content Knowledge on Pedagogical Content Knowledge: The case of teaching photosynthesis and plant growth. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2009, 31, 1395–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, V. Pedagogical content knowledge in science education: Perspectives and potential for progress. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2009, 45, 169–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, L. Knowing and Teaching Elementary Mathematics: Teachers’ Understanding of Fundamental Mathematics in China and the United States; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Driel, J.H.; de Jong, O.; Verloop, N. The Development of Preservice Chemistry Teachers’ Pedagogical Content Knowledge. Sci. Educ. 2002, 86, 572–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Großschedl, J.; Harms, U.; Kleickmann, T.; Glowinski, I. Preservice Biology Teachers’ Professional Knowledge: Structure and Learning Opportunities. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2015, 26, 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riese, J.; Reinhold, P. Die professionelle Kompetenz angehender Physiklehrkräfte in verschiedenen Ausbildungsformen. Empirische Hinweise für eine Verbesserung des Lehramtsstudiums. Z. Erzieh. 2012, 15, 111–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollny, S.; Tepner, O. CK und PCK von Chemielehrkräften—Unterschiede und Zusammenhänge. In Konzepte fachdidaktischer Strukturierung für den Unterricht, Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Society for the Principles of Teaching Chemistry and Physics (GDCP), Oldenburg, Germany, 19–22 November 2011; Bernholt, S., Ed.; LIT-Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2012; pp. 212–214. [Google Scholar]

- Riese, J.; Reinhold, P. Empirische Erkenntnisse zur Struktur professioneller Handlungskompetenz von angehenden Physiklehrkräften. Z. Didakt. Nat. 2010, 16, 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Rohaan, E.J. Testing Teacher Knowledge for Technology Teaching in Primary Schools. Ph.D. Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröbst, S.; Kleickmann, T.; Heinze, A.; Anschütz, A.; Rink, R.; Kunter, M. Teacher knowledge experiment: Testing mechanisms underlying the formation of preservice elementary school teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge concerning fractions and fractional arithmetic. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 110, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromme, R. Kompetenzen, Funktionen und unterrichtliches Handeln des Lehrers. In Enzyklopädie der Psychologie. Serie 1: Pädagogische Psychologie. Psychologie des Unterrichts und der Schule; Weinert, F.E., Ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 1997; Volume 3, pp. 177–212. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, K. Professionelle Kompetenzen von Lehrkräften im Sachunterricht. In Handbuch Didaktik des Sachunterrichts, 2nd ed.; Kahlert, J., Fölling-Albers, M., Götz, M., Hartinger, A., Miller, S., Wittkowske, S., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2015; pp. 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kallery, M. Early-Years Teachers’ Professional Upgrading in Science: A Long-Term Programme. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 437–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabel, J.L.; Forbes, C.T.; Flynn, L. Elementary teachers’ use of content knowledge to evaluate students’ thinking in the life sciences. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2016, 38, 1077–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.T.; Heaton, R.M.; Prawat, R.S.; Remillard, J. Teaching Mathematics for Understanding: Discussing Case Studies of Four Fifth-Grade Teachers. Elem. Sch. J. 1992, 93, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, K.; Tippins, D.J.; Gallard, A.J. Research on Instructional Strategies for Teaching Science. In Handbook of Research on Science Teaching and Learning; Gabel, D.L., Ed.; Macmillan Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 45–93. [Google Scholar]

- Baumert, J.; Blum, W.; Neubrand, M. Drawing the lessons from PISA 2000. Z. Erzieh. 2004, 7, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luera, G.R.; Moyer, R.H.; Everett, S.A. What type and level of science content knowledge of elementary education students affect their ability to construct an inquiry-based science lesson? J. Elem. Sci. Educ. 2005, 17, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohaan, E.J.; Taconis, R.; Jochems, W.M.G. Analysing teacher knowledge for technology education in primary schools. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2012, 22, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schoon, K.J.; Boone, W.J. Self-efficacy and alternative conceptions of science of preservice elementary teachers. Sci. Educ. 1998, 82, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velthuis, C.; Fisser, P.; Pieters, J. Teacher Training and Pre-service Primary Teachers’ Self-Efficacy for Science Teaching. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2014, 25, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heller, J.I.; Daehler, K.R.; Wong, N.; Shinohara, M.; Miratrix, L. Differential Effects of Three Professional Development Models on Teacher Knowledge and Student Achievement in Elementary Science. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2012, 49, 333–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, H.C.; Rowan, B.; Ball, D.L. Effects of Teachers’ Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching on Student Achievement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2005, 42, 371–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ohle, A.; Fischer, H.E.; Kauertz, A. Der Einfluss des physikalischen Fachwissens von Primarstufenlehrkräften auf Unterrichtsgestaltung und Schülerleistung. Z. Didakt. Nat. 2011, 17, 357–389. [Google Scholar]

- Secretariat of the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Länder in the Federal Republic of Germany. Ländergemeinsame Inhaltliche Anforderungen für Die Fachwissenschaften und Fachdidaktiken in der Lehrerbildung (Beschluss vom 16.10.2008 i. d. F. vom 16.05.2019). Available online: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2008/2008_10_16-Fachprofile-Lehrerbildung.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Blömeke, S.; Kaiser, G.; Lehmann, R.; König, J.; Döhrmann, M.; Buchholtz, C.; Hacke, S. TEDS-M: Messung von Lehrerkompetenzen im internationalen Vergleich. In Lehrprofessionalität. Bedingungen, Genese, Wirkungen und Ihre Messung; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Beck, K., Sembrill, D., Nickolaus, R., Mulder, R., Eds.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2009; pp. 181–210. [Google Scholar]

- Anders, Y.; Hardy, I.; Sodian, B.; Steffensky, M. Zieldimensionen naturwissenschaftlicher Bildung im Grundschulalter und ihre Messung. In Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zur Arbeit der Stiftung “Haus der Kleinen Forschung”; der Kleinen Forscher, S.H., Ed.; SCHUBI Lernmedien: Schaffhausen, Germany, 2013; pp. 83–146. [Google Scholar]

- Döhrmann, M.; Kaiser, G.; Blömeke, S. The Conceptualisation of Mathematics Competencies in the International Teacher Education Study TEDS-M. In International Perspectives on Teacher Knowledge, Beliefs and Opportunities to Learn; Blömeke, S., Hsieh, F.-J., Kaiser, G., Schmidt, W.H., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 431–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohle, A. Primary School Teachers’ Content Knowledge in Physics and Its Impact on Teaching and Students’ Achievement; Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tatto, M.T.; Schwille, J.; Senk, S.L.; Ingvarson, L.; Peck, R.; Rowley, G. Teacher Education and Development Study in Mathematics (TEDS-M). Policy, Practice, and Readiness to Teach. Primary and Secondary Mathematics. Conceptual Framework; Teacher Education and Development International Study Center, College of Education, Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ohle, A.; Boone, W.J.; Fischer, H.E. Investigating the impact of teachers’ physics CK on students outcomes. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2015, 13, 1211–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzi, H.J.; White, R.T. Change in teachers’ knowledge of subject matter: A 17-year longitudinal study. Sci. Educ. 2008, 92, 221–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, M.; Kunter, M.; Krauss, S.; Baumert, J.; Blum, W.; Dubberke, T.; Jordan, A.; Klusmann, U.; Tsai, Y.M.; Neubrand, M. Welche Zusammenhänge bestehen zwischen dem fachspezifischen Professionswissen von Mathematiklehrern und ihrer Ausbildung sowie beruflichen Fortbildung? Z. Erzieh. 2006, 9, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, M.; Kruger, C. A longitudinal study of constructivist approach to improving primary science teachers’ subject matter knowledge in science. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1994, 10, 499–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, J.; Schaal, S.; Heran-Dörr, E. Fachwissen von Lehramtsstudierenden zum Thema “Leben in extremen klimatischen Bedingungen”—Erhebung des Fachwissens im Rahmen einer Interventionsstudie. J. GDSU 2013, 3, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone, L.M. Improving Impact Studies of Teachers’ Professional Development: Toward Better Conceptualizations and Measures. Educ. Res. 2009, 38, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Möller, K. Konstruktivistische Sichtweisen für das Lernen in der Grundschule? In Forschungen zu Lehr—Und Lernkonzepten für Die Grundschule (Jahrbuch Grundschulforschung, 4); Roßbach, H.-G., Nölle, K., Czerwenka, K., Eds.; Leske + Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 2001; pp. 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Riemeier, T. Moderater Konstruktivismus. In Theorien in der Biologiedidaktischen Forschung; Krüger, D., Vogt, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, K.; Hardy, I.; Jonen, A.; Kleickmann, T.; Blumberg, E. Naturwissenschaften in der Primarstufe. Zur Förderung konzeptuellen Verständnisses durch Unterricht und zur Wirksamkeit von Lehrerfortbildungen. In Untersuchungen zur Bildungsqualität von Schule. Abschlussbericht des DFG-Schwerpunktprogramms BiQua; Prenzel, M., Allolio-Näcke, L., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2006; pp. 161–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kunter, M.; Klusmann, U.; Baumert, J.; Richter, D.; Voss, T.; Hachfeld, A. Professional competences of teachers: Effects on instructional quality and student development. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavelson, R.J.; Hubner, J.J.; Stanton, G.C. Self-Concept: Validation of Construct Interpretations. Rev. Educ. Res. 1976, 46, 407–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazvini, S.D. Relationships between Academic Self-concept and Academic Performance in High School Students. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 1034–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Möller, J.; Trautwein, U. Selbstkonzept. In Pädagogische Psychologie, 2nd ed.; Wild, E., Möller, J., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Shavelson, R.J. Self-Concept: Its Multifaceted, Hierarchical Structure. Educ. Psychol. 1985, 20, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Byrne, B.M.; Shavelson, R.J. A multifaceted academic self-concept: Its hierarchical structure and its relation to academic achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 1988, 80, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W. The structure of academic self-concept: The Marsh/Shavelson model. J. Educ. Psychol. 1990, 82, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, J.; Köller, O. Die Genese akademischer Selbstkonzepte. Psychol. Rundsch. 2004, 55, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenstedt, V. Pilotierung eines Fragebogens zur Erhebung des Technischen Selbstkonzepts von durchschnittlich Neunjährigen. J. Tech. Educ. 2018, 6, 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Paulick, I.; Großschedl, J.; Harms, U.; Möller, J. Preservice Teachers’ Professional Knowledge and Its Relation to Academic Self-Concept. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 67, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorge, S.; Keller, M.M.; Neumann, K.; Möller, J. Investigating the relationship between pre-service physics teachers’ professional knowledge, self-concept, and interest. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2019, 56, 937–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleickmann, T.; Tröbst, S.; Jonen, A.; Vehmeyer, J.; Möller, K. The Effects of Expert Scaffolding in Elementary Science Professional Development on Teachers’ Beliefs and Motivations, Instructional Practices, and Student Achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 108, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschel, M. SelfPro: Entwicklung von Professionsverständnissen und Selbstkonzepten angehender Lehrkräfte beim Offenen Experimentieren. In Profession und Disziplin. Jahrbuch Grundschulforschung; Miller, S., Holler-Nowitzki, B., Kottmann, B., Lesemann, S., Letmathe-Henkel, B., Meyer, N., Schroeder, R., Velten, K., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; Volume 22, pp. 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.K. Mit biologischen Inhalten Brücken zur Chemie bauen. Entwicklung und Erprobung Eines Seminars für Sachunterrichtsstudierende. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel-Busse, K.; Kastens, C.P.; Kucharz, D. Fachspezifisch oder nicht?—Eine Studie zur Analyse der Binnenstruktur des Selbstkonzepts Sachunterricht. Z. Grund. 2018, 11, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. The development of achievement task values: A theoretical analysis. Dev. Rev. 1992, 12, 265–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmke, A.; van Aken, M.A.G. The causal ordering of academic achievement and self-concept of ability during elementary school: A longitudinal study. J. Educ. Psychol. 1995, 87, 624–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, J.C.; DuBois, D.L.; Cooper, H. The Relation Between Self-Beliefs and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Review. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 39, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskey, T.R. Teacher efficacy, self-concept, and attitudes toward the implementation of instructional innovation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1988, 4, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.M. The Prediction of Teacher Burnout through Personality Type, Critical Thinking, and Self-Concept. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Mid-South Educational Research Association, Mobile, AL, USA, 11–13 November 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Aspy, D.N.; Buhler, J.H. The Effect of Teacher’s Inferred Self Concept upon Student Achievement. J. Educ. Res. 1975, 68, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Craven, R.G. Reciprocal Effects of Self-Concept and Performance from a Multidimensional Perspective: Beyond Seductive Pleasure and Unidimensional Perspectives. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 1, 133–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, H.C. The Nature and Predictors of Elementary Teachers’ Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching. J. Res. Math. Educ. 2010, 41, 513–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, M.; Damerau, K.; Preisfeld, A. A scientific out-of-school programme on neurobiology employing CLIL. Its impact on the cognitive acquisition and experimentation-related ability self-concepts. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2018, 13, 647–660. [Google Scholar]

- Damerau, K. Molekulare und Zell-Biologie im Schülerlabor. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wuppertal, Wuppertal, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Paulick, I.; Großschedl, J.; Harms, U.; Möller, J. How teachers perceive their expertise: The role of dimensional and social comparisons. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Salah Abduljabbar, A.; Parker, P.D.; Abdelfattah, F.; Nagengast, B.; Möller, J.; Abu-Hilal, M.M. The Internal/External Frame of Reference Model of Self-Concept and Achievement Relations: Age-Cohort and Cross-Cultural Differences. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 52, 168–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, F.; Helm, F.; Zimmermann, F.; Nagy, G.; Möller, J. On the Effects of Social, Temporal, and Dimensional Comparisons on Academic Self-Concept. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 110, 1005–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, M.; Skaalvik, E.M. Academic Self-Concept and Self-Efficacy: How Different Are They Really? Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 15, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdtke, O.; Köller, O.; Marsh, H.W.; Trautwein, U. Teacher frame of reference and the big-fish-little-pond effect. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 30, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beudels, M.; Preisfeld, A.; Damerau, K. Impact of an Experiment-Based Intervention on Pre-Service Primary School Teachers’ Experiment-Related and Science Teaching-Related Self-Concepts. Interdiscip. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2022, 18, e2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, N.; Damerau, K.; Preisfeld, A. “Experimentieren kann ich gut!“—Experimentbezogene Fähigkeitsselbstkonzepte von Lehramtsstudierenden der Fächer Biologie, Chemie und Sachunterricht. Z. Didakt. Biol.-Biol. Lehre. Lern. 2020, 24, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labudde, P. Fächerübergreifender naturwissenschaftlicher Unterricht—Mythen, Definitionen, Fakten. Z. Didakt. Nat. 2014, 20, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwichow, M.; Zaki, K.; Hellmann, K.; Kreutz, J. Quo vadis? Kohärenz in der Lehrerbildung. In Kohärenz in der Lehrerbildung; Hellmann, K., Kreutz, J., Schwichow, M., Zaki, K., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labudde, P. Fächerübergreifender Unterricht in und mit Physik: Eine zu wenig genutzte Chance. PhyDid-A 2003, 1, 48–66. [Google Scholar]

- Aström, M. Defining Integrated Science Education and Putting It to Test. Ph.D. Thesis, Linköping University, Norrköping, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, D.; Sadler, T.D. Preservice Elementary Teachers’ Science Self-Efficacy Beliefs and Science Content Knowledge. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2016, 27, 649–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niermann, A. Professionswissen von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern des Mathematik—und Sachunterrichts; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes, A. Zur Wirksamkeit von Integriertem Naturwissenschaftlichem Unterricht. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Kassel, Kassel, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Statistical Office. Lehrkräfte nach Schularten und Beschäftigung. Schuljahr 2019/20. Stand: 20. Oktober 2020. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bildung-Forschung-Kultur/Schulen/Tabellen/allgemeinbildende-beruflicheschulen-lehrkraefte.html (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Rehfeldt, D.; Straube, P.; Köster, H. Längsschnittstudie im Grundschulpädagogik-Sachunterrichtsstudium: Selbstkonzepte & Überzeugungen (1-Jahres-Daten). In Naturwissenschaftliche Kompetenzen in der Gesellschaft von Morgen, Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Society for the Principles of Teaching Chemistry and Physics (GDCP), Wien, Australia, 9–12 September 2019; Habig, S., Ed.; University of Duisburg-Essen: Duisburg/Essen, Germany, 2020; pp. 924–927. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, H.; Peters, B. Blockveranstaltungen—Lehrformat für Eine Heterogene Studierendenschaft; Discussion Paper 1; Zentrum für Hochschulbildung, TU Dortmund University: Dortmund, Germany, 2012; Available online: https://d-nb.info/1112267018/34 (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- French, S. The Benefits and Challenges of Modular Higher Education Curricula; Issues and Ideas Paper; Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education, The University of Melbourne: Parkville, Australia, 2015; Available online: https://melbourne-cshe.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/2774391/Benefits_Challenges_Modular_Higher_Ed_Curricula_SFrench_v3-green-2.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Samarawickrema, G.; Cleary, K. Block Mode Study: Opportunities and Challenges for a New Generation of Learners in an Australian University. Stud. Success 2021, 12, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, S.; Nesbit, P.L. Block or traditional? An analysis of student choice of teaching format. J. Manag. Organ. 2008, 14, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holley, D.; Park, S. Lessons learned around the block: An analysis of research on the impact of block scheduling on science teaching and learning. In Education Research Highlights in Mathematics, Science, and Technology; Shelley, M., Pehlivan, M., Eds.; ISRES Publishing: Ames, IA, USA, 2017; pp. 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, L.; O’Gorman, V. ‘Block teaching’—exploring lecturers’ perceptions of intensive modes of delivery in the context of undergraduate education. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilkenmeier, J.; Sommer, S. Praxisnahe Fallarbeit—Block versus wöchentliches Seminar. Ein Vergleich zweier Veranstaltungsformate in der Lehrerinnen—und Lehrerbildung. Beiträge Lehr.-Lehr. 2014, 32, 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, C.; Haag, J. Ich könnte nie wieder zu einem‚ normalen “Stundenplan zurück!”—Zur Reorganisation der Lehre in einem Bachelor-Studiengang IT Security. In HDI 2012—Informatik für Eine Nachhaltige Zukunft, Proceedings of the 5th Symposium Hochschuldidaktik der Informatik, Hamburg, Germany, 6–7 November 2012; Forbrig, P., Rick, D., Schmolitzky, A., Eds.; Universitätsverlag Potsdam: Potsdam, Germany, 2013; pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kucsera, J.V.; Zimmaro, D.M. Comparing the Effectiveness of Intensive and Traditional Courses. Coll. Teach. 2010, 58, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caskey, S.R. Learning Outcomes in Intensive Courses. J. Contin. High. Educ. 1994, 42, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, E.L. A Review of Time-Shortened Courses across Disciplines. Coll. Stud. J. 2000, 34, 298–308. [Google Scholar]

- Schaal, S.; Randler, S. Konzeption und Evaluation eines computergestützten kooperativen Blockseminars zur Systematik der Blütenpflanzen. Z. Hochsch. 2004, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Scyoc, L.J.; Gleason, J. Traditional or Intensive Course Lengths? A Comparison of Outcomes in Economics Learning. J. Econ. Educ. 1993, 24, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henebry, K. The Impact of Class Schedule on Student Performance in a Financial Management Course. J. Educ. Bus. 1997, 73, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrowsky, M.C. The Two Week Summer Macroeconomics Course: Success or Failure; Glendale Community College: Glendale, AZ, USA, 1996. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED396779.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- McCreary, J.; Hausman, C. Differences in Student Outcomes between Block, Semester, and Trimester Schedules; University of Utah: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2001. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED457590.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Wilson, E.; Looney, S.; Stair, K. The Impact of Block Scheduling on Agricultural Education: A Nine Year Comparative Study. J. Career Tech. Educ. 2005, 22, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spence, M.J. Block Versus Traditional Scheduling in High School: Teacher and Student Attitudes. Ph.D. Thesis, Lindenwood University, St. Charles, MO, USA, 1 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhan, L.; Wang, Y.; Du, X.; Zhou, W.; Ning, X.; Sun, Q.; Moscovitch, M. Effects of learning experience on forgetting rates of item and associative memories. Learn. Mem. 2016, 23, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bateson, D.J. Science Achievement in Semester and All-Year Courses. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1990, 27, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodzinski, R. Physikalische Fachkonzepte anbahnen—Anschlussfähigkeit verbessern. In Physikdidaktik Grundlagen, 4th ed.; Kircher, E., Girdwidz, R., Fischer, H.E., Eds.; Springer Spektrum: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 573–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, C. Kohärenz und Relationierung in der Lehrerinnen—und Lehrerbildung. In Handbuch Lehrerinnen—und Lehrerbildung; Cramer, C., König, J., Rothland, M., Blömeke, S., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2020; pp. 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C.; Kranich, K.; Eisele, M. Block scheduled versus traditional biology teaching—An educational experiment using the water lily. Instr. Sci. 2008, 36, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beudels, M.; Schilling, Y.; Preisfeld, A. Mit Experimenten zu Wasserläufer & Co Kohärenz Erleben—Potenziale Eines Interdisziplinären, Experimentellen Kurses zur Professionalisierung Angehender Sachunterrichtslehrkräfte. DiMaWe. Under Review.

- Kaiser, A. Praxisbuch Handelnder Sachunterricht (Band 4); Schneider Hohengehren: Baltmannsweiler, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenschein, M. Teaching to Understand: On the Concept of the Exemplary in Teaching. In Teaching as A Reflective Practice. The German Didaktik Tradition; Westbury, I., Hopmann, S.T., Riquarts, K., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry for School and Further Education North Rhine-Westphalia (MSW NRW). Richtlinien und Lehrpläne für die Grundschule in Nordrhein-Westfalen; Ritterbach: Frechen, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Macke, G.; Hanke, U.; Viehmann-Schweizer, P.; Raether, W. Kompetenzorientierte Hochschuldidaktik, 3rd ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Prenzel, M.; Geiser, H.; Langeheine, R.; Lobemeier, K. Das naturwissenschaftliche Verständnis am Ende der Grundschule. In Erste Ergebnisse aus IGLU; Bos, W., Lankes, E.-M., Prenzel, M., Schwippert, K., Valtin, R., Walther, G., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2003; pp. 143–187. [Google Scholar]

- Stampfl, M.; Saurer, W. Hinterlässt der Physikunterricht Spuren?—Das Interesse am Physikunterricht im Rückblick von Studierenden. PhyDid A-Phys. Didakt. Sch. Hochsch. 2020, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, G.J.; Strike, K.A.; Hewson, P.W.; Gertzog, W.A. Accommodation of a Scientific Conception: Toward a Theory of Conceptual Change. Sci. Educ. 1982, 66, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giest, H. Die Naturwissenschaftliche Perspektive Konkret; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mammes, I.; Zolg, M. Technische Aspekte. In Handbuch Didaktik des Sachunterrichts, 2nd ed.; Kahlert, J., Fölling-Albers, M., Götz, M., Hartinger, A., Miller, S., Wittkowske, S., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2015; pp. 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- SoSci Survey (Computer Software). Available online: https://www.soscisurvey.de/ (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Rost, J. Lehrbuch Testtheorie—Testkonstruktion, 2nd ed.; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, A.; Huxham, G.J. Comparison of multiple-choice and essay testing in preclinical physiology. Br. J. Med. Educ. 1970, 4, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgeman, B.; Lewis, C. The Relationship of Essay and Multiple-choice Scores with Grades in College Courses. J. Educ. Meas. 1994, 31, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strack, F. “Order Effects” in Survey Research: Activation and Information Functions of Preceding Questions. In Context Effects in Social and Psychological Research; Schwarz, N., Sudman, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühner, M. Einführung in Die Test—Und Fragebogenkonstruktion, 4th ed.; Pearson: München, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kauertz, A.; Kleickmann, T.; Ewerhardy, A.; Fricke, K.; Lange, K.; Ohle, A.; Pollmeier, K.; Tröbst, S.; Walper, L.; Fischer, H.; et al. Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente im Projekt PLUS; Forschergruppe und Graduiertenkolleg nwu-essen: Duisburg/Essen, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Rice, J. Little Jiffy, Mark IV. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Laatz, W. Statistische Datenanalyse Mit SPSS, 9th ed.; Springer Gabler: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. The Effect of Standardization on a Chi Square Approximation in Factor Analysis. Biometrika 1951, 38, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, K.; Erichson, B.; Wulff, P.; Weiber, R. Multivariate Analysemethoden, 15th ed.; Springer Gabler: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noormann, P. Mehrstufige Eigenmarken—Eine Empirische Analyse von Zielen, Erfolgsdeterminanten und Grenzen; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, S. Faktoren—Und Reliabilitätsanalyse [Factor and Reliability Analysis]. In Datenanalyse mit SPSS für Fortgeschrittene 2: Multivariate Verfahren für Querschnittsdaten; Fromm, S., Ed.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 53–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Widaman, K.F.; Zhang, S.; Hong, S. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, N.; Bortz, J. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in Den Sozial—Und Humanwissenschaften, 5th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. 11.0 Update, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rasch, B.; Friese, M.; Hofmann, W.; Naumann, E. Quantitative Methoden 2, 4th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girden, E.R. ANOVA: Repeated Measures; Sage University Papers; Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences: No. 07-084; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rasch, B.; Friese, M.; Hofmann, W.; Naumann, E. Quantitative Methoden 1, 4th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, R.; Koster, C.J. Empirie in Linguistik und Sprachlehrforschung. In Ein Methodologisches Arbeitsbuch; Narr: Tübingen, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bühl, A. Einführung in Die Moderne Datenanalyse ab SPSS 25, 16th ed.; Pearson: Hallbergmoos, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, M.; Schroeders, U.; Lüdtke, O.; Pant, H.A. Der Einfluss interdisziplinärer Beschulung auf die Struktur des akademischen Selbstkonzepts in den naturwissenschaftlichen Fächern. Z. Pädagog. Psychol. 2014, 28, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M. Academic Self-Concept in the Sciences: Domain-Specific Differentiation, Gender Differences, and Dimensional Comparison Effects. In Self: Driving Positive Psychology and Well-Being; Guay, F., Marsh, H.W., McInerney, D.M., Craven, R.G., Eds.; IAP Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2017; pp. 71–112. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, J.; Marsh, H.W. Dimensional comparison theory. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 120, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Trautwein, U.; Lüdtke, O.; Köller, O.; Baumert, J. Academic Self-Concept, Interest, Grades, and Standardized Test Scores: Reciprocal Effects Models of Causal Ordering. Child. Dev. 2005, 76, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canady, R.L. Parallel Block Scheduling: A Better Way to Organize School. Principal 1990, 69, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, P.A. Attributes of high-quality intensive courses. New Dir. Adult Cont. Educ. 2003, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M. Intensive teaching formats: A review. Issues Educ. Res. 2006, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Groß, L.; Aufenanger, S. Wie wirken didaktische Elemente der Hochschullehre auf die zeitliche Gestaltung des Studiums? Z. Hochsch. 2011, 6, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, D. Lernen im Beruf. In Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften. Ergebnisse des Forschungsprogramms COACTIV; Kunter, M., Baumert, J., Blum, W., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., Neubrand, M., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2011; pp. 317–327. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, H.C.; Schilling, S.G.; Ball, D.L. Developing Measures of Teachers’ Mathematics Knowledge for Teaching. Elem. Sch. J. 2004, 105, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fendler, L. Ethical implications of validity-vs.-reliability trade-offs in educational research. Ethics Educ. 2016, 11, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phakiti, A. Experimental Research Methods in Language Learning; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, K.; Ohle, A.; Kleickmann, T.; Kauertz, A.; Möller, K.; Fischer, H.E. Zur Bedeutung von Fachwissen und fachdidaktischem Wissen für Lernfortschritte von Grundschülerinnen und Grundschülern im naturwissenschaftlichen Sachunterricht. Z. Grund. 2015, 8, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hasler, M. Bionik: Klettverschluss, Flugzeug und Co; Lernbiene: Bavaria, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kalusche, D.; Kremer, B.P. Biologie in der Grundschule. In Spannende Projekte für Einen Lebendigen Unterricht und für Arbeitsgemeinschaften; Schneider Hohengehren: Baltmannsweiler, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barthlott, W.; Neinhuis, C. Lotus-Effekt und Autolack: Die Selbstreinigungsfähigkeit mikrostrukturierter Oberflächen. Biol. Zeit 1998, 28, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, G.; Pietrzyk, U.; Schneider, K.; Willmer-Klumpp, C. Naturwissenschaften Kompakt Gymnasium Sek. I; Ernst Klett: Stuttgart, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Job, G.; Rüffler, R. Physikalische Chemie. Eine Einführung Nach Neuem Konzept mit Zahlreichen Experimenten; Vieweg+Teubner/Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nachtigall, W. Bionik als Wissenschaft. Erkennen—Abstrahieren—Umsetzen; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachtigall, W.; Pohl, G. Bau-Bionik. Natur—Analogien—Technik, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachtigall, W.; Wisser, A. Bionik in Beispielen. 250 Illustrierte Ansätze; Springer Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchers, J. Spannende Sachtexte zum Körper. Kopiervorlagen für den Deutsch—Und Sachunterricht ab 2. Klasse, 5th ed.; Persen: Hamburg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Drechsler-Köhler, B. Bausteine Sachunterricht 4 für Nordrhein-Westfalen; Diesterweg: Braunschweig, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ganser, B.; Simon, I. Forscher Unterwegs; Brigg Pädagogik: Augsburg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, M.; Hartinger, A. Experimentieren im Sachunterricht; Cornelsen Scriptor: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, S.; Hoenecke, C. Lernen an Stationen—Themenheft “Experimentieren mit Luft: 3./4. Schuljahr”; Cornelsen Scriptor: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, V.; Mederow, G. Naturwissenschaften Biologie—Chemie—Physik: Luft; Volk und Wissen Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, E. Atmung: Lernen an Stationen im Biologieunterricht (7. und 8. Klasse), 2nd ed.; Auer: Augsburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Asselborn, W.; Jäckel, M.; Risch, K.T.; Sieve, B.F. Chemie heute SI—Gesamtband; Schroedel Verlag: Hannover, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bannwarth, H.; Kremer, B.P.; Schulz, A. Basiswissen Physik, Chemie und Biochemie. Vom Atom. Bis zur Atmung—Für Biologen, Mediziner und Pharmazeuten, 3rd ed.; Springer Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, A. Humanbiologie für Lehramtsstudierende. Ein Arbeits—Und Studienbuch; Springer Spektrum: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, W.; Clauss, C. Humanbiologie Kompakt; Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Dietrich, L. Chemie für Biologen. Von Studierenden für Studierende erklärt; Springer Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subscales | Number of Items | Original Item | Item Translation | Item Abbreviation (Pre/Post) | rit (Pre/Post) | Cronbach’s α (Pre/Post) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| biology-related ASC | 3 | Biologie liegt mir nicht besonders *. | Biology doesn’t come easily to me *. | TU31_03/NT19_11 | 0.650/0.724 | 0.845/0.862 |

| Ich bin gut in Biologie. | I am good at biology. | TU31_05/NT19_01 | 0.768/0.787 | |||

| Mir fällt es leicht, neue Inhalte im Fach Biologie zu verstehen. | I find it easy to understand new content in biology. | TU31_08/NT19_06 | 0.732/0.708 | |||

| chemistry-related ASC | 3 | Chemie liegt mir nicht besonders *. | Chemistry doesn’t come easily to me *. | TU31_06/NT19_05 | 0.853/0.850 | 0.934/0.919 |

| Ich bin gut in Chemie. | I am good at chemistry. | TU31_11/NT19_10 | 0.879/0.871 | |||

| Mir fällt es leicht, neue Inhalte im Fach Chemie zu verstehen. | I find it easy to understand new content in chemistry. | TU31_13/NT19_12 | 0.863/0.805 | |||

| physics-related ASC | 3 | Ich bin gut in Physik. | I am good at physics. | TU31_09/NT19_18 | 0.846/0.898 | 0.924/0.928 |

| Mir fällt es leicht, neue Inhalte im Fach Physik zu verstehen. | I find it easy to understand new content in physics. | TU31_14/NT19_15 | 0.844/0.840 | |||

| Physik liegt mir nicht besonders *. | Physics doesn’t come easily to me *. | TU31_16/NT19_08 | 0.857/0.833 | |||

| technology-related ASC | 3 | Ich bin gut in Technik. | I am good at technology. | TU31_02/NT19_04 | 0.761/0.840 | 0.863/0.890 |

| Technik liegt mir nicht besonders *. | Technology doesn’t come easily to me *. | TU31_15/NT19_14 | 0.720/0.779 | |||

| Mir fällt es leicht, neue Inhalte im Fach Technik zu verstehen. | I find it easy to understand new content in technology. | TU31_17/NT19_17 | 0.745/0.750 |

| Group | Reference Time | M | SD | p | ηp2 | pgroups | ηp, groups2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG | Pre | 36.61 | 8.61 | 0.000 *** | 0.686 | 0.000 *** | 0.285 |

| Post | 53.18 | 9.99 | |||||

| Follow-up | 51.66 | 9.28 | |||||

| BG | Pre | 36.45 | 6.70 | 0.142 | 0.044 | ||

| Post | 36.23 | 9.43 | |||||

| Follow-up | 37.93 | 7.74 |

| Scale | Group | Reference Time | M | SD | p | ηp2 | pgroups | ηp, groups2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| biology-related ASC | EG | Pre | 3.74 | 0.90 | 0.000 *** | 0.252 | 0.002 ** | 0.047 |

| Post | 4.10 | 0.79 | ||||||

| BG | Pre | 3.93 | 0.75 | 0.486 | 0.011 | |||

| Post | 3.98 | 0.69 | ||||||

| chemistry-related ASC | EG | Pre | 3.02 | 1.09 | 0.000 *** | 0.215 | 0.001 *** | 0.052 |

| Post | 3.43 | 0.99 | ||||||

| BG | Pre | 2.71 | 1.03 | 0.929 | 0.000 | |||

| Post | 2.70 | 1.07 | ||||||

| physics-related ASC | EG | Pre | 3.06 | 1.05 | 0.000 *** | 0.132 | 0.011 * | 0.032 |

| Post | 3.32 | 0.98 | ||||||

| BG | Pre | 2.74 | 0.93 | 0.822 | 0.001 | |||

| Post | 2.73 | 0.95 | ||||||

| technology-related ASC | EG | Pre | 3.20 | 0.90 | 0.000 *** | 0.273 | 0.000 *** | 0.083 |

| Post | 3.64 | 0.86 | ||||||

| BG | Pre | 3.19 | 0.94 | 0.470 | 0.012 | |||

| Post | 3.12 | 0.87 |

| Group | Reference Time | M | SD | p | ηp2 | pgroups | ηp, groups2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| weekly | Pre | 38.31 | 8.80 | (0.000 ***)/[0.000 ***] | (0.627)/[0.612] | (Post: 0.000 ***), (Follow-up 0.038 *)/ [Post 0.000 ***], [Follow-up 0.066] | (Post 0.088), (Follow-up 0.028)/ [Post 0.080], [Follow-up 0.022] |

| Post | 51.99 | 9.76 | |||||

| Follow-up | 51.60 | 8.85 | |||||

| block | Pre | 34.49 | 7.93 | (0.000 ***)/[0.000 ***] | (0.793)/[0.793] | ||

| Post | 54.67 | 10.14 | |||||

| Follow-up | 51.73 | 9.86 |

| Scale | Group | Reference Time | M | SD | p | ηp2 | pgroups | ηp, groups2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| biology-related ASC | weekly | Pre | 3.74 | 0.87 | (0.000 ***)/[0.000 ***] | (0.187)/[0.139] | (0.442)/[0.326] | (0.004)/[0.006] |

| Post | 4.06 | 0.77 | ||||||

| block | Pre | 3.74 | 0.93 | (0.000 ***)/[0.000 ***] | (0.386)/[0.374] | |||

| Post | 4.14 | 0.81 | ||||||

| chemistry-related ASC | weekly | Pre | 3.02 | 1.10 | (0.000 ***)/[0.000 ***] | (0.230)/[0.232] | (0.647)/[0.849] | (0.001)/[0.000] |

| Post | 3.42 | 1.01 | ||||||

| block | Pre | 3.01 | 1.08 | (0.000 ***)/[0.000 ***] | (0.225)/[0.217] | |||

| Post | 3.43 | 0.97 | ||||||

| physics-related ASC | weekly | Pre | 3.08 | 1.09 | (0.000 ***)/[0.000 ***] | (0.133)/[0.138] | (0.716)/[0.528] | (0.001)/[0.003] |

| Post | 3.38 | 1.04 | ||||||

| block | Pre | 3.03 | 1.02 | (0.001 ***)/[0.001 ***] | (0.157)/[0.153] | |||

| Post | 3.26 | 0.92 | ||||||

| technology-related ASC | weekly | Pre | 3.20 | 0.85 | (0.000 ***)/[0.000 ***] | (0.276)/[0.294] | (0.962)/[0.736] | (0.000)/[0.001] |

| Post | 3.67 | 0.88 | ||||||

| block | Pre | 3.19 | 0.96 | (0.000 ***)/[0.000 ***] | (0.340)/[0.346] | |||

| Post | 3.60 | 0.85 |

| Group | Subgroup | Reference Time | M | SD | p | ηp2 | pgroups | ηp, groups2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| weekly | SciTec | Pre | 39.90 | 9.08 | 0.000 *** | 0.599 | 0.836 (Post), 0.595 (Follow-up) | 0.001 (Post), 0.003 (Follow-up) |

| Post | 52.55 | 9.93 | ||||||

| Follow-up | 52.07 | 8.99 | ||||||

| non-SciTec | Pre | 34.89 | 7.19 | 0.000 *** | 0.670 | |||

| Post | 50.79 | 9.45 | ||||||

| Follow-up | 50.61 | 8.60 | ||||||

| block | SciTec | Pre | 35.42 | 7.77 | 0.000 *** | 0.756 | 0.005 ** | 0.076 |

| Post | 53.36 | 9.98 | ||||||

| Follow-up | 50.87 | 9.87 | ||||||

| non-SciTec | Pre | 32.80 | 8.08 | 0.000 *** | 0.842 | |||

| Post | 57.04 | 10.20 | ||||||

| Follow-up | 53.28 | 9.86 |

| Scale | Group | Subgroup | Reference Time | M | SD | p | ηp2 | pgroups | ηp, groups2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| biology-related ASC | weekly | SciTec | Pre | 3.82 | 0.88 | 0.000 *** | 0.226 | 0.365 | 0.010 |

| Post | 4.19 | 0.76 | |||||||

| non-SciTec | Pre | 3.56 | 0.85 | 0.106 | 0.094 | ||||

| Post | 3.79 | 0.72 | |||||||

| block | SciTec | Pre | 3.83 | 0.81 | 0.000 *** | 0.456 | 0.870 | 0.000 | |

| Post | 4.22 | 0.65 | |||||||

| non-SciTec | Pre | 3.59 | 1.11 | 0.003 ** | 0.318 | ||||

| Post | 4.00 | 1.04 | |||||||

| chemistry-related ASC | weekly | SciTec | Pre | 3.31 | 1.04 | 0.000 *** | 0.195 | 0.473 | 0.006 |

| Post | 3.65 | 0.97 | |||||||

| non-SciTec | Pre | 2.42 | 0.97 | 0.002 ** | 0.302 | ||||

| Post | 2.93 | 0.93 | |||||||

| block | SciTec | Pre | 3.18 | 1.04 | 0.000 *** | 0.294 | 0.255 | 0.019 | |

| Post | 3.51 | 0.96 | |||||||

| non-SciTec | Pre | 2.72 | 1.12 | 0.027 * | 0.187 | ||||

| Post | 3.29 | 1.01 | |||||||

| physics-related ASC | weekly | SciTec | Pre | 3.43 | 0.96 | 0.023 * | 0.084 | 0.310 | 0.012 |

| Post | 3.67 | 0.94 | |||||||

| non-SciTec | Pre | 2.35 | 0.99 | 0.004 ** | 0.272 | ||||

| Post | 2.75 | 0.97 | |||||||

| block | SciTec | Pre | 3.19 | 0.99 | 0.011 * | 0.139 | 0.320 | 0.019 | |

| Post | 3.36 | 1.01 | |||||||

| non-SciTec | Pre | 2.75 | 1.03 | 0.041 * | 0.162 | ||||

| Post | 3.07 | 0.68 | |||||||

| technology-related ASC | weekly | SciTec | Pre | 3.54 | 0.70 | 0.001 *** | 0.182 | 0.336 | 0.012 |

| Post | 3.92 | 0.77 | |||||||

| non-SciTec | Pre | 2.48 | 0.68 | 0.000 *** | 0.548 | ||||

| Post | 3.13 | 0.85 | |||||||

| block | SciTec | Pre | 3.62 | 0.70 | 0.001 *** | 0.237 | 0.660 | 0.003 | |

| Post | 3.86 | 0.72 | |||||||

| non-SciTec | Pre | 2.41 | 0.88 | 0.001 *** | 0.397 | ||||

| Post | 3.13 | 0.89 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beudels, M.M.; Damerau, K.; Preisfeld, A. Effects of an Interdisciplinary Course on Pre-Service Primary Teachers’ Content Knowledge and Academic Self-Concepts in Science and Technology–A Quantitative Longitudinal Study. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110744

Beudels MM, Damerau K, Preisfeld A. Effects of an Interdisciplinary Course on Pre-Service Primary Teachers’ Content Knowledge and Academic Self-Concepts in Science and Technology–A Quantitative Longitudinal Study. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(11):744. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110744

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeudels, Melanie Marita, Karsten Damerau, and Angelika Preisfeld. 2021. "Effects of an Interdisciplinary Course on Pre-Service Primary Teachers’ Content Knowledge and Academic Self-Concepts in Science and Technology–A Quantitative Longitudinal Study" Education Sciences 11, no. 11: 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110744

APA StyleBeudels, M. M., Damerau, K., & Preisfeld, A. (2021). Effects of an Interdisciplinary Course on Pre-Service Primary Teachers’ Content Knowledge and Academic Self-Concepts in Science and Technology–A Quantitative Longitudinal Study. Education Sciences, 11(11), 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110744