Capacity Building for Internationalization at a Technical University in Kazakhstan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. About the Project

- (i)

- institutional commitment;

- (ii)

- administrative leadership, structure, and staffing;

- (iii)

- curriculum, co-curriculum, and learning outcomes;

- (iv)

- faculty policies and practices;

- (v)

- student mobility;

- (vi)

- collaboration and partnership; and

- (vii)

- research and development.

- (i)

- Analysis of benchmarking of higher education internationalization;

- (ii)

- Study of domestic and foreign internationalization of universities’ education processes; and

- (iii)

- Analysis of project experiences and preparation of recommendations for implementation of changes.

3. Benchmarking of Internationalization Process at a Technical University

- (i)

- Reciprocity—when activities are based on mutual relations, agreement, and data exchange;

- (ii)

- Analogy—when the operational processes of partners should be similar;

- (iii)

- Measurement—when comparing the characteristics measured at several enterprises; and

- (iv)

- Reliability—when actual data are applied, including an accurate analysis of the implementation and study of the process.

- (i)

- Planning;

- (ii)

- Analysis;

- (iii)

- Projecting and correlation;

- (iv)

- Measurement management; and

- (v)

- Implementation of solutions and progress monitoring aimed at sustainable capacity building of the internationalization of higher education.

- (i)

- An increased degree of interest and participation in identifying benchmarking criteria;

- (ii)

- Consideration of the trends in educational policy development;

- (iii)

- Choosing a system or methodology that collects primary data and determines the level of their reliability; and

- (iv)

- Analysis and interpretation of the data obtained based on the proposed indicators.

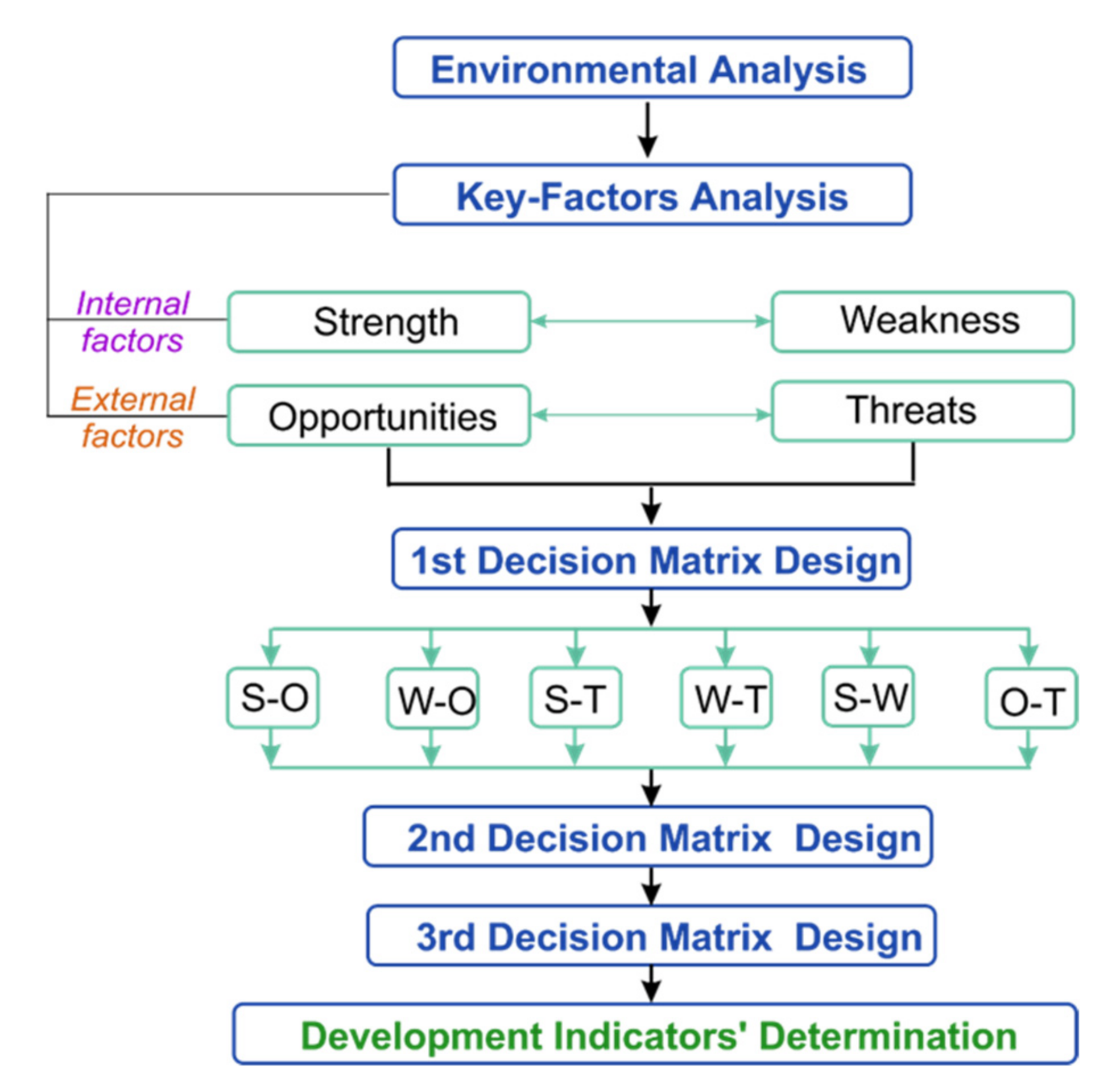

4. SWOT Analysis of Capacity for Internationalization at the KTU

- (i)

- Institutional Commitment—Internationalization at the university level, the role of internationalization in the strategic development plan and the mission of the university, financing of internationalization, and the assessment of the current progress and impact of internationalization on the university and its further directions;

- (ii)

- Administrative Leadership, Structure, Staffing—Administrative management, management structure, work with administrative personnel, roles of senior managers, the division of labor across administrative offices, and the professional development of administrative staff;

- (iii)

- Curriculum, Co-curriculum, Learning outcomes—Internationalization of curricula and extracurricular activities, and evaluating student academic requirements and learning outcomes;

- (iv)

- Faculty Policies and Practices—Faculty member recruitment, awards, and professional development;

- (v)

- Student Mobility—Student mobility (incoming and outgoing mobility), recruitment of international students, support for international students (e.g., language courses, programs of acquaintance with the culture of the country), preparation of Kazakhstani students for studying abroad, administration and financing of exchange programs for Kazakhstani students;

- (vi)

- Collaboration and Partnership—Inter-university partnership, double-degree programs, image and representation of universities internationally; and

- (vii)

- In addition, we singled out as a separate category that focuses on Partnership in Research and Development with foreign universities.

- (i)

- S-O line of strength—identifying strengths and opportunities for development;

- (ii)

- W-O line of improvement—including the intended levelling of shortcomings;

- (iii)

- S-T line of defense—defining the line of advantages to protecting against uncontrolled external factors; and

- (iv)

- W-T line of warning—identifying measures necessary to prevent future risks.

- (i)

- Strengths—SN; N-sequence number of factor;

- (ii)

- Weaknesses—WN; N-sequence number of factor;

- (iii)

- Opportunities—ON; N-sequence number of factor; and

- (iv)

- Threats—TN, N-sequence number of factor.

5. Evaluation of the Development of Internationalization through a Survey

- (i)

- International joint research programs;

- (ii)

- International research centers;

- (iii)

- International researchers;

- (iv)

- Internationally recognized research achievements;

- (v)

- International students;

- (vi)

- Student mobility;

- (vii)

- International profile of the faculty;

- (viii)

- International view and experience of the faculty;

- (ix)

- Courses with an international component;

- (x)

- Joint programs;

- (xi)

- Students’ participation in international research;

- (xii)

- Human resources for international activities;

- (xiii)

- Financial support for internationalization;

- (xiv)

- International alumni presence;

- (xv)

- International networks and partnerships.

- (i)

- 1—the direction of development is not taken into account;

- (ii)

- 2—is implemented at the formal level;

- (iii)

- 3—is not implemented systematically;

- (iv)

- 4—a sufficient level for positioning the university at the international level;

- (v)

- 5—a high level of implementation.

5.1. The “Research and Development” Group

5.2. The “Student Mobility” Group

5.3. The “Faculty Policies and Practices” Group

5.4. The “Curriculum” Group

5.5. The “Institutional Commitment” Group

5.6. “Collaboration and Partnership” Group

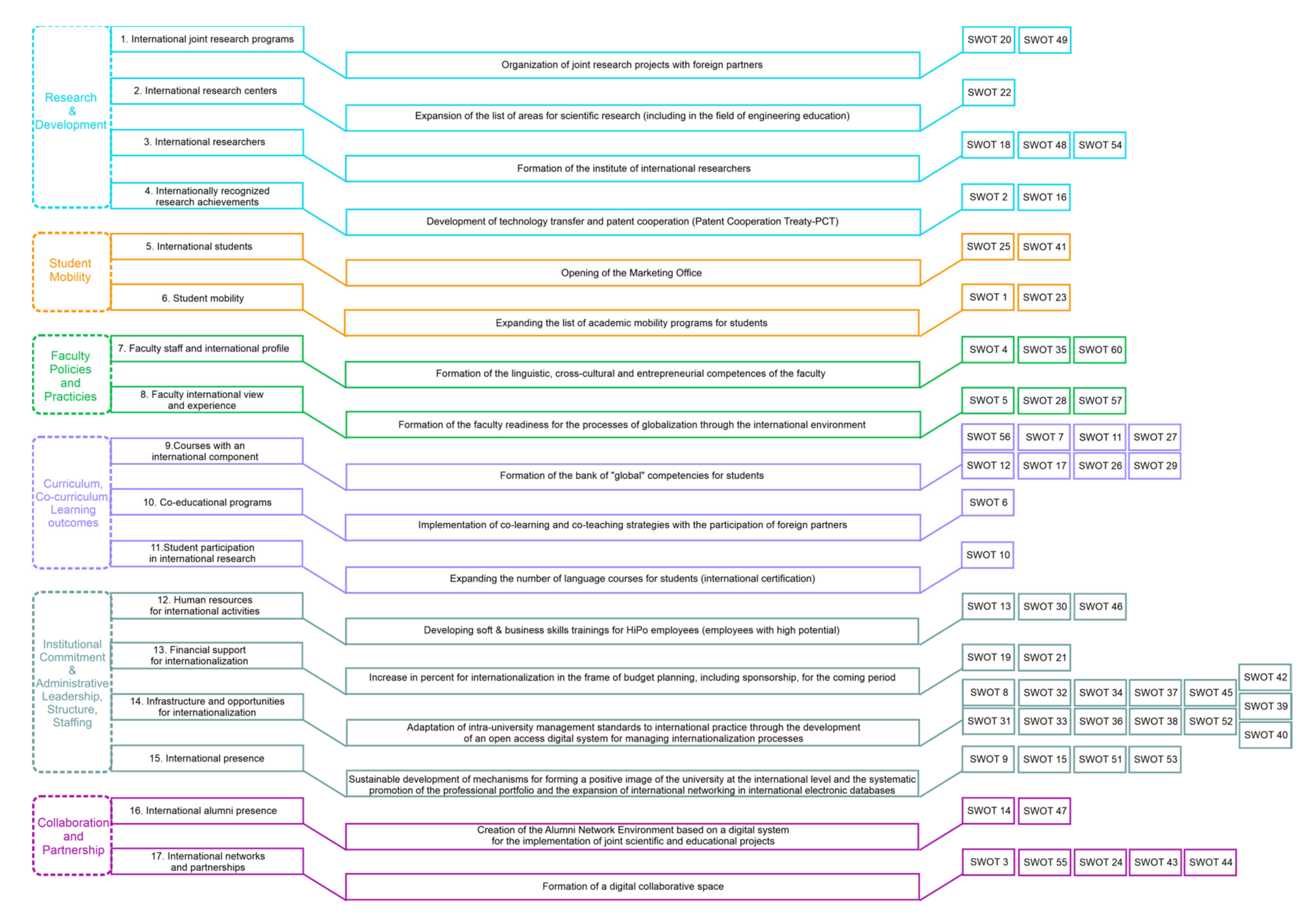

6. SWOT and Benchmarking

- (i)

- Organization of joint research with foreign partners;

- (ii)

- Expansion of the list of areas of scientific research (including in the field of education and technical profile of the university);

- (iii)

- Formation of the Institute of International Researchers;

- (iv)

- Development of technology transfer and patent cooperation (Patent Cooperation Treaty-PCT);

- (v)

- Opening of the Marketing Office;

- (vi)

- Expanding the list of academic mobility programs for students.

- (vii)

- Formation of the linguistic, cross-cultural, and entrepreneurial competence of faculty.

- (viii)

- Formation of faculty readiness for the processes of globalization through the international environment.

- (ix)

- Formation of the bank of “global” competencies (global issues) of students.

- (x)

- Implementation of co-learning and co-teaching strategies with the participation of foreign partners.

- (xi)

- Expanding the number of language training students (international certification).

- (xii)

- Organization of soft and business skills training for HiPo employees (employees with high potential).

- (xiii)

- Increasing the share of internationalization expenditures in budget planning for the coming period, including sponsorship development.

- (xiv)

- Adaptation of intra-university management standards to international practice by developing an open-access information system for managing internationalization processes.

- (xv)

- Sustainable development of mechanisms for forming a positive image of the university in the international arena, systematic promotion of the professional portfolio, and expanding global networking in international electronic databases.

- (xvi)

- Creation of the Alumni Network Environment based on an information system to implement joint scientific and educational projects.

- (xvii)

- Formation of digital collaborative space.

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- State Program of Development of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2020–2025. Available online: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/edu/press/article/details/20392?lang=ru (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Action Plan for the Implementation of the State Program for the Development of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2020–2025. Available online: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/edu/documents/details/64163?lang=ru (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Yean, T.S. Internationalizing Higher Education in Malaysia: Understanding, Practices and Challenges; Institute of Southeast Studies: Singapore, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hudzik, J.K. Comprehensive Internationalization: From Concept to Action; NAFSA: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, D.-A.C. Comprehensive Internationalization: Examining the What, Why, and How at Community Colleges. Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1463428422. 2016. Available online: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=etd (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- American Council on Education. Mapping Internationalization on U.S. Campuses: 2017 Edition. 2017. Available online: https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Mapping-Internationalization-2017.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- QS. North American International Partnership and Agreement Practices Survey 2021 Results. 2021. Available online: https://www.qs.com/portfolio-items/north-american-survey-results-2021/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Joint Statement of Principles in Support of International Education. 2021. Available online: https://educationusa.state.gov/us-higher-education-professionals/us-government-resources-and-guidance/joint-statement (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Association of International Education Administrators. Standards of Professional Practice for International Education Leaders and Senior International Officers. Available online: https://www.aieaworld.org/standards-of-professional-practice (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- NAFSA. NAFSA’s Statement of Ethical Principles. 2019. Available online: https://www.nafsa.org/about-us/about-nafsa/nafsas-statement-ethical-principles (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- The Forum on Education Abroad. Code of Ethics for Education Abroad, 3rd ed. 2020. Available online: https://forumea.org/resources/standards-6th-edition/code-of-ethics/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- International Association of Universities. Affirming Academic Values in Internationalization of Higher Education: A Call for Action. 2012. Available online: https://www.iau-aiu.net/IMG/pdf/affirming_academic_values_in_internationalization_of_higher_education.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- American Council on Education. International Higher Education Partnerships: CIGE Insights a Global Review of Standards and Practices. 2015. Available online: https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/CIGE-Insights-Intl-Higher-Ed-Partnerships.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Internationalization in Kazakhstani Universities: Learning from the Regions: British Council Project. Available online: https://www.britishcouncil.kz/ru/programmes/education/ihe (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Ilie, A.G.; Maftei, M.; Colibasanu, O.A. Sustainable success in higher education by sharing the best practices as a result of benchmarking process. Amfiteatru Econ. 2011, 13, 688–697. [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev, E.A.; Evdokimova, Y.S. Benchmarking dlya Vuzov: Uchebno-Metodicheskoe Posobie (Benchmarking for Universities: An Educational and Methodological Guide); Universitetskaya Kniga, Logos: Moscow, Russia, 2006; pp. 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J.M. Internationalization Remodeled: Definition, Approaches, and Rationales. J Stud. Int. Educ. 2004, 8, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasopoulou, K.; Tsiotras, G. Benchmarking towards excellence in higher education. Bench. Int. J. 2017, 24, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifanova, S.A. Benchmarking v sfere obrazovatel’nyh uslug (Benchmarking in the field of educational services). J. Siber. Med. Sci. 2008, 1, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell, B.; Maldonado-Maldonado, A. Four stories: Confronting contemporary ideas about globalization and internationalization in higher education. Glob. Soc. Ed. 2009, 7, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.W. Developing Holistic Indicators to Promote the Internationalization of Higher Education in the Asia-Pacific. UNESCO Asia-Pacific Education Policy Brief; UNESCO Office: Bangkok, Thailand, 2018; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000266241 (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Coleman, C.; Narayanan, D.; Kang, D.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, J.; Nardi, L.; Bailis, P.; Olukotun, K.; Ré, C.; Zaharia, M. DAWN Bench: An End-to-End Deep Learning Benchmark and Competition. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. A set of indicators for measuring and comparing university internationalization performance across national boundaries. High. Educ. 2018, 76, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.-F.; Lin, N.-J. Applying CIPO indicators to examine internationalization in higher education institutions in Taiwan. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2018, 63, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulter, L. Legal issues in benchmarking. Bench. Int. J. 2003, 10, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchmarking—ISO Consultant in Kuwait. Available online: https://isoconsultantkuwait.com/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- KTU Policy and Goals in the Field of Quality. Available online: https://www.kstu.kz/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Politika-tseli.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- KTU Academic Policy. Available online: https://www.kstu.kz/akademicheskaya-politika-vuza/ (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- KTU Anti-Corruption Standard. Available online: https://www.kstu.kz/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Antikorruptsionnyj-standart-KarGTU.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- KTU Rules of Ethics. Available online: https://www.kstu.kz/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Pravila-etiki-KarGTU-2020.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Fahim, A.; Tan, Q.; Naz, B.; Ain, Q.U.; Bazai, S.U. Sustainable Higher Education Reform Quality Assessment Using SWOT Analysis with Integration of AHP and Entropy Models: A Case Study of Morocco. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahijan, M.K.; Rezaei, S.; Preece, C.N. Developing a framework of internationalization for higher education institutions in Malaysia: A SWOT analysis. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2016, 10, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, E. Embracing the global: The role of ranking, research mandate, and sector in the internationalisation of higher education. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, H. Global and national prominent universities: Internationalization, competitiveness and the role of the State. High. Educ. 2009, 58, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohajionu, U.C. Internationalisation of the curriculum in Malaysian Universities’ business faculties: Realities, implementation and challeges. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Internal Commitment factors | Strength (S) | Weakness (W) |

| 1. Institutional Commitment 1.1. Rating positions

| 1. Institutional Commitment 1.1. Low interest of the faculty and scholars in participating in the international projects. 1.2. Low level of membership in international associations. 1.3. Insufficient digitalization of the educational process. 1.4. The library collection is mainly in Kazakh and Russian languages. 1.5. Insufficient funding for international projects at the expense of government funding or extrabudgetary funds of KTU. 1.6. Low level of participation in international educational fairs and forums. | |

| 2. Administrative Leadership, Structure, Staffing 2.1. A government policy has been implemented in the administrative structure of KTU. 2.2. Transfer from permissive to consultative management style at KTU. 2.3. An incentive scheme and the HiPos’ system have been developed. | 2. Administrative Leadership, Structure, Staffing 2.1. Lack of transparency in administrative management processes. 2.2. Lack of interconnection between intra-university processes. 2.3. Low level of time management. 2.4. Qualification requirements of administrative staff have been partially accorded with international standards. 2.5. Insufficient elaboration of internationalization issues in the internal strategic documents of the university. 2.6. Low level of administrative staff’s digital competencies. 2.7. Insufficient involvement of the faculty and students in corporate governance processes. |

| Scheme | ||

|---|---|---|

| Strength | Opportunities | Strategy |

| 1. Institutional Commitment | ||

1.1. Rating positions

| 1.1. Leading position in training specialists in technical areas among the universities in Central Asia. 1.2. Improving the QS rating positions. 1.3. The development of alumni association for supportive collaboration. |

|

| 2. Administrative Leadership, Structure, Staffing | ||

| 2.1. A government policy has been implemented in the administrative structure of KTU. 2.2. Transfer from permissive to consultative management style of KTU. 2.3. An incentive scheme and the HiPos’ system have been developed. | 2.1. Annual training courses for administrative staff in management and communication skills at national and international levels. |

|

| Institutional Commitment | ||

|---|---|---|

| Internal factors External factors | Strength | Weakness |

1.1. Rating positions

| 1.1. Low interest of the faculty and scholars in participating in the international projects. 1.2. Low level of membership in international associations. 1.3. Insufficient digitalization of an educational process. 1.4. The library collection is mainly in Kazakh and Russian languages. 1.5. Insufficient funding for international projects at the expense of government funding or extrabudgetary funds of KTU. 1.6. Low level of participation in international educational fairs and forums. | |

| Opportunities | Possible strategies: | Possible strategies: |

| 1.1. Leading position in the field of technical specialists training among the Central Asia universities. 1.2. Improving the QS rating positions. 1.3. The alumni association’s development for supportive collaboration. |

|

|

| Threats | Possible strategies: | Possible strategies: |

|

|

|

| № | Strategies | Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Commitment | ||

| 1 | To increase the level of foreign partners’ involvement in exchange programs | W1, W6, T3 |

| 2 | To sign partnership agreements with foreign universities | W1, T6, W4 |

| 3 | To provide the university with English-language electronic library resources due to cooperation with partners abroad | O1, O2, W3, W4, T6 |

| 4 | To provide the permanent presence and presentation of the university at the international level by sending faculty and scholars to international conferences, seminars, and forums to increase the rating and recognition of the university | T1, T2, T3, W2, W6 |

| 5 | To develop a map of critical competencies and career skills for students/future engineers, being ready for participation in education abroad via the exchange programs and having a high level of language proficiency and academic skills | O1, O2, T2, T3, T6 |

| 6 | To identify new components of the curriculum for implementation, taking into account international academic requirements for students | T3, T6, W2 |

| 7 | To open the university official representative office abroad | T6, W2 |

| 8 | To improve the quality of technical education per international standards | S1, O2, T2, T3 |

| 9 | To search for new programs and awards for funding collaborative initiatives | W2, O1, T1, T4, W1, W5 |

| 10 | To provide recruitment and support of international students | W4, W6, T8 |

| 11 | To develop cooperation with foreign publishers and organizations, providing electronic resources | W4, W6 |

| 12 | To develop the intra-university standards of administrative processes, including internationalization policy | O1, T5, T7, W2 |

| 13 | To develop a digital system for ensuring the implementation of internationalization strategies through the creation of a specialized digital interaction system, including the modelling of e-learning to form the professional language competence of future engineers | T2, T3, T7, W3, W4 |

| 14 | To create the university marketing service | O1, O2, T5, T6 |

| 15 | To create an open interactive digital platform for finding potential sponsors or partners to participate in key foreign educational events and projects | S1, O2, W3, W5 |

| 16 | To develop a road map with a partner university before signing a new agreement | O1 |

| 17 | To create a system of incentives for faculty and scholars to expand international cooperation and to form a network of international collaborators | O1, T1, T4 |

| 18 | To create a special interaction service for communication with graduates, including those living abroad | O2 |

| 19 | To encourage the participation of the faculty and scholars in international projects | W1, O1 |

| 20 | To increase the percentage of membership in international associations | W1, O1, O2 |

| 21 | To increase the level of participation in international fairs | W6, O1 |

| 22 | To take part in the exchange programs Erasmus+, DAAD, and Fulbright | O1, T5, T6 |

| № | Indicators |

|---|---|

| 1 | Active involvement of existing foreign partners in academic mobility programs |

| 2 | Implementation of research results or applied research in the real sector of the economy |

| 3 | Resumption of work under previously concluded contracts |

| 4 | Allocation of budgetary funds for language support of teachers for conducting classes in three languages |

| 5 | Identification of priority areas for advanced training of the teaching staff, including the development of language and digital competencies, and intercultural communications |

| 6 | Conclusion of partnership agreements with universities from far abroad |

| 7 | Ensuring the continuity of curricula |

| 8 | Providing the university with English-language electronic library resources through cooperation with foreign partners |

| 9 | Ensuring the constant presence and presentation of the university in the international arena by sending teaching staff and scientists to international conferences, seminars, and forums to increase the rating and recognition of the university |

| 10 | Providing language support in preparation for entrance exams for master’s and doctoral studies |

| 11 | Determination of critical competencies and skills in readiness for the careers of students/future engineers in international companies, preparation of future technical specialists for training in other countries and with the presence of the necessary foreign language and educational outlook |

| 12 | Definition of new components of implementation in curricula, taking into account international academic requirements for students |

| 13 | Organization of courses on the development of “soft skills” and business administration skills for teaching staff and scientists |

| 14 | Organization of postgraduate accompaniment of graduates |

| 15 | Opening of the official representative office of the university abroad |

| 16 | Translation of the accumulated materials into English to publish them in international journals |

| 17 | Improving the quality of technical education per international standards |

| 18 | Improving the quality of preparation of articles in English for the publication of research results for submission to the international scientific community |

| 19 | Search for funding mechanisms for educational, scientific, and sports student initiatives, in addition to budget funds to reduce dependence on republican funding |

| 20 | Search for new foreign partners to motivate scientific personnel |

| 21 | Search for new sources of funding for the organization of mobility and internships for teaching staff |

| 22 | Search for new areas of cooperation within the educational activities of the university, as well as the provision of specialized services based on existing institutions of the university |

| 23 | Search for new programs for the organization of academic mobility of students, funded by extrabudgetary funds and funds of the university |

| 24 | Search for new programs and competitions for financing collaboration initiatives |

| 25 | Attracting and supporting international students |

| 26 | Involvement of foreign scientists for consultations on the development of curricula in the framework of partnership agreements |

| 27 | Involvement of regional and foreign employers in the definition of key competencies of graduates to create a base of key competencies of graduates that meet international standards |

| 28 | Application of international practice of creating a support group for postgraduate support and undergraduate study programs |

| 29 | Application of research results in the development of educational programs |

| 30 | Conducting training, round tables, and refresher courses, including with the participation of foreign specialists, for administrative workers involved in managing the process of the internationalization of the university |

| 31 | Development of cooperation with foreign publications and electronic resources. |

| 32 | Development of intra-university standards for administrative processes in the field of internationalization |

| 33 | Development of an information system that ensures the implementation of internationalization strategies through the creation of a specialized system of digital interaction, including modelling an e-learning space to form professional foreign language competence of future engineers |

| 34 | Development of corporate management standards |

| 35 | Development of a methodology for the language training of university staff and students as a condition for the development of key methodological competencies for teaching and learning in English |

| 36 | Development of mechanisms for the interaction of all subjects of the educational process of internationalization through an integrated information learning system |

| 37 | Development of an open dialogue platform to attract foreign partners to conduct scientific research and commercialize the results obtained |

| 38 | Compliance and development of algorithms for administrative management processes, transparency, and interconnection |

| 39 | Improving the library system to increase the availability of resources for students |

| 40 | Creation of infrastructure to support the introduction of new technologies in teaching, research, and management |

| 41 | Marketing service creation |

| 42 | Creation of a new proprietary information resource to neutralize threats during training using DLE |

| 43 | Creation of an open dialogue digital platform for finding potential sponsors/partners to participate in key foreign educational events and projects |

| 44 | Creation of an action plan with a partner university before concluding a new contract |

| 45 | Creation of a network library with foreign partners |

| 46 | Creation of an incentive system for teaching staff and scientists to expand international cooperation and form a network of international collaborators |

| 47 | Creation of a specialized service for communication and interaction with graduates, including those living abroad |

| 48 | Encouraging young scientists to conduct research and obtain doctoral qualifications |

| 49 | Encouraging teaching staff and scientists to participate in international projects |

| 50 | Stimulating the entrepreneurial activity of teaching staff and students, including for participation in projects to find sponsors for the implementation of start-ups |

| 51 | Increasing the share of membership in international associations |

| 52 | Increasing the amount of electronic content on the university website in English |

| 53 | Increased participation in international exhibitions. |

| 54 | Increasing the participation of teaching staff and scientists at international seminars, conferences, and forums |

| 55 | Establishing and strengthening ties with regional and republican industries |

| 56 | Participation in foreign courses to improve the qualifications of teaching staff on the use of DLE |

| 57 | Participation in exchange programs like Erasmus+, DAAD, and Fulbright |

| Categories | Share Distribution of Level of Internationalization Development* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| R&D | |||||

| International cooperative research programs | 20% | - | 40% | 40% | - |

| International-focused research centers | 20% | 20% | 20% | 40% | - |

| International researchers | 10% | - | 40% | 40% | 10% |

| Internationally acknowledged research achievements | 10% | 10% | 40% | 40% | - |

| Student | |||||

| International students | 10% | 10% | 40% | 40% | - |

| Mobility of students | 10% | - | 20% | 60% | 10% |

| Faculty | |||||

| The international profile of the faculty team | 10% | 30% | 30% | 10% | 20% |

| International perspective and experience of faculty | 20% | 10% | 40% | 20% | 10% |

| Curriculum | |||||

| Courses with international components | 20% | 10% | 40% | 20% | 10% |

| Joint degree programs | 20% | 20% | 40% | 20% | - |

| Students’ participation in international studies | 10% | - | 40% | 40% | 10% |

| Administration | |||||

| Human resources for international activities | 10% | 30% | 30% | 30% | - |

| Financial support for internationalization | 10% | 30% | 40% | 20% | - |

| Infrastructure and facilities for internationalization | 10% | 20% | 40% | 30% | - |

| International presence | 20% | 50% | 10% | 20% | - |

| Engagement | |||||

| The international presence of alumni | 20% | 10% | 50% | 20% | - |

| International networks and partnerships | 10% | 20% | 40% | 30% | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jantassova, D.; Churchill, D.; Kozhanbergenova, A.; Shebalina, O. Capacity Building for Internationalization at a Technical University in Kazakhstan. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110735

Jantassova D, Churchill D, Kozhanbergenova A, Shebalina O. Capacity Building for Internationalization at a Technical University in Kazakhstan. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(11):735. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110735

Chicago/Turabian StyleJantassova, Damira, Daniel Churchill, Aigerim Kozhanbergenova, and Olga Shebalina. 2021. "Capacity Building for Internationalization at a Technical University in Kazakhstan" Education Sciences 11, no. 11: 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110735

APA StyleJantassova, D., Churchill, D., Kozhanbergenova, A., & Shebalina, O. (2021). Capacity Building for Internationalization at a Technical University in Kazakhstan. Education Sciences, 11(11), 735. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110735