Equity Gaps in Education: Nine Points toward More Transparency

Abstract

:1. Equity Gaps in Education: Nine Points toward More Transparency

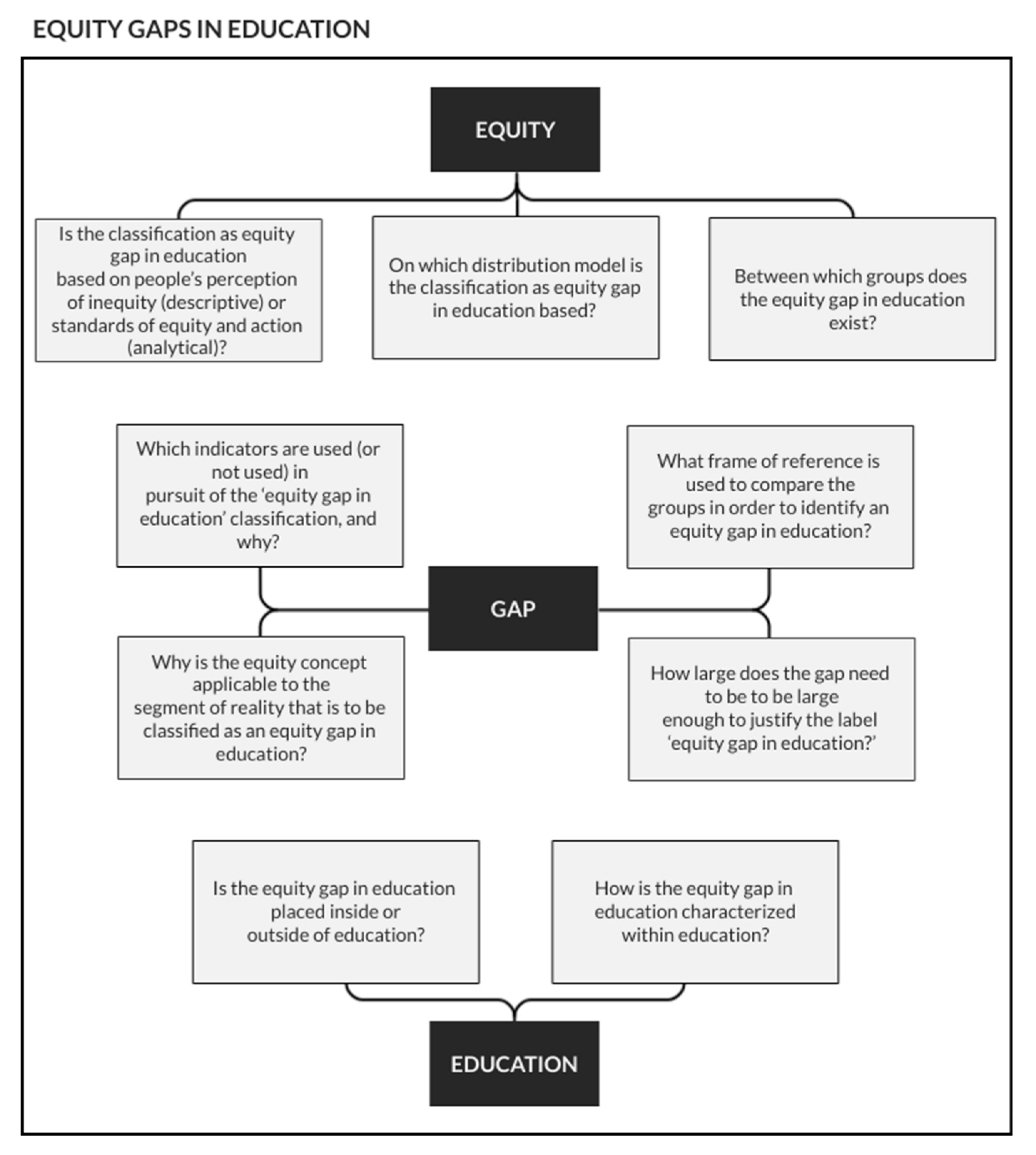

2. Equity Gaps in Education

3. Transparency

- As stakeholder A, I want to understand information from stakeholder B, so that I can make full use of the information in my decision-making.

- As stakeholder A, I want to give information to stakeholder B, so that stakeholder B can understand the information and make full use of it in their decision-making.

4. Equity

4.1. Descriptive or Analytical Equity Models

4.2. Distribution Model

4.3. Groups

5. The Gap

5.1. Applicability Issue

5.2. Indicator Issue

5.3. Reference Issue

5.4. Significance Issue

6. Education

6.1. Placing the Equity Gap Inside or Outside of Education

6.2. Characterization of the Equity Gap within Education

- Opportunity gaps denote unequitable input of (educational) processes; for example, resources, opportunities, access to infrastructure, and learning opportunities.

- Learning gaps denote unequitable capacities to take advantage of opportunities, resources, access to infrastructure, and learning opportunities.

- Outcome gaps denote unequitable output of (educational) processes, e.g., participation rates, learning outcomes, achievements, and rewards.

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Landis, S.C.; Amara, S.G.; Asadullah, K.; Austin, C.P.; Blumenstein, R.; Bradley, E.W.; Crystal, R.G.; Darnell, R.B.; Ferrante, R.J.; Fillit, H.; et al. A call for transparent reporting to optimize the predictive value of preclinical research. Nature 2012, 490, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iqbal, S.A.; Wallach, J.D.; Khoury, M.J.; Schully, S.D.; Ioannidis, J.P. Reproducible Research Practices and Transparency across the Biomedical Literature. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damian, E.; Meuleman, B.; van Oorschot, W. Transparency and Replication in Cross-national Survey Research: Identification of Problems and Possible Solutions. Sociol. Methods Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G.; Kaplan, S.; Whittington, R. Editorial Essay: The Tumult over Transparency: Decoupling Transparency from Replication in Establishing Trustworthy Qualitative Research. Adm. Sci. Q. 2020, 65, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.; Joye, D.; Smith, T.; Fu, Y.-C. The SAGE Handbook of Survey Methodology; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- CONSORT. CONSORT: Transparent Reporting of Trials. 2010. Available online: http://www.consort-statement.org/home/ (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- American Psychological Association. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, K.M.; Koenka, A.C.; Sanchez, C.E.; Moshontz, H.; Cooper, H. Reporting standards for literature searches and report inclusion criteria: Making research syntheses more transparent and easy to replicate. Res. Synth. Methods 2015, 6, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Solarino, A.M. Transparency and replicability in qualitative research: The case of interviews with elite informants. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 1291–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamra, G.B.; Goldstein, N.D.; Harper, S. Resource Sharing to Improve Research Quality. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e012292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López-Nicolás, R.; López-López, J.A.; Rubio-Aparicio, M.; Sánchez-Meca, J. A meta-review of transparency and reproducibility-related reporting practices in published meta-analyses on clinical psychological interventions (2000–2020). Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauh, S.; Torgerson, T.; Johnson, A.L.; Pollard, J.; Tritz, D.; Vassar, M. Reproducible and transparent research practices in published neurology research. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2020, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.; Talbot, D.; Mayes, E. Diffractive accounts of inequality in education: Making the effects of differences evident. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2020, 33, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Sustainable Development Goal 4: Targets and Indicators. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg4#targets (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- UNESCO. Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4. Towards Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Lifelong Learning Opportunities for All. UNESDOC Digital Library. 2015. Available online: https://iite.unesco.org/publications/education-2030-incheon-declaration-framework-action-towards-inclusive-equitable-quality-education-lifelong-learning/ (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Welch, A.; Connell, R.; Mockler, N.; Sriprakash, A.; Proctor, H.; Hayes, D.; Foley, D.; Vickers, M.; Bagnall, N.; Burns, K.; et al. Education, Change and Society, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K. A Review of Evidence about Equitable School Leadership. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown McNair, T.; Bensimon, E.; Malcom-Piqueux, L. From Equity Talk to Equity Walk: Expanding Practitioner Knowledge for Racial Justice in Higher Education; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow, M.; Dyson, A.; Goldrick, S.; West, M. Developing Equitable Education Systems; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jurado de los Santos, P.; Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J.; Marín-Marín, J.-A.; Soler Costa, R. The term equity in education: A literature review with scientific mapping in Web of Science. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S.J. New class inequalities in education. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2010, 30, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, J.L. Social Class in Public Schools. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 821–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muller, C. Standards and Equity. J. Learn. Sci. 2004, 13, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brayboy, B.M.J.; Castagno, A.E.; Maughan, E. Chapter 6 Equality and Justice For All? Examining Race in Education Scholarship. Rev. Res. Educ. 2007, 31, 159–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.R. Race without racism: How higher education researchers minimize racist institutional norms. Rev. High. Educ. 2012, 36, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez Heilig, J.; Brown, K.; Brown, A. The illusion of inclusion: A critical race theory textual analysis of race and standards. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2012, 82, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasen, S. Low Schooling for Girls, Slower Growth for All? Cross-Country Evidence on the Effect of Gender Inequality in Education on Economic Development. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2002, 16, 345–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meinck, S.; Brese, F. Trends in gender gaps: Using 20 years of evidence from TIMSS. Large-Scale Assess. Educ. 2019, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNESCO. Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2015: Gender Summary. 2015. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/report/2015/education-all-2000-2015-achievements-and-challenges (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Airton, L.; Koecher, A. How to hit a moving target: 35 years of gender and sexual diversity in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 80, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgett, M.V.L.Y.; Frank, J. (Eds.) Sexual Orientation Discrimination: An International Perspective; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw, J.; Greytak, E.; Diaz, E.; Bartkiewicz, M. The 2009 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools; Gay, Lesbian Straight Education Network: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- García, E.; Weiss, E. Reducing and Averting Achievement Gaps; Economic Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shores, K.; Kim, H.E.; Still, M. Categorical Inequality in Black and White: Linking Disproportionality Across Multiple Educational Outcomes. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 57, 2089–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstegen, D.A. On Doing an Analysis of Equity and Closing the Opportunity Gap. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2015, 23, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roche, R.; Manzi, J. Bridging the confidence gap: Raising self-efficacy amongst urban high school girls through STEM education. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. Res. 2019, 5, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strietholt, R. Studying educational inequality: Reintroducing Normative Notions. In Educational Policy Evaluation through International Comparative Assessments; Strietholt, R., Bos, W., Gustafsson, J.-E., Rosén, M., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2014; pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow, M. Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2020, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noguera, P.; Pierce, J.; Ahram, R. Race, Equity, and Education: Sixty Years from Brown; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Adapting Curriculum to Bridge Equity Gaps; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, N.M.; Markus, H.R.; Fryberg, S.A. Social class disparities in health and education: Reducing inequality by applying a sociocultural self model of behavior. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 119, 723–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannister, N.A. Breaking the spell of differentiated instruction through equity pedagogy and teacher community. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2016, 11, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee Banks, C.A.; Banks, J.A. Equity pedagogy: An essential component of multicultural education. Theory Pract. 1995, 34, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, P.; Pitt, T.; Thomas, O. Bewitched by our words: Wittgenstein, language-games, and the pictures that hold sport psychology captive. Sport Exerc. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 10, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hjørland, B. Concept theory. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 1519–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppe, F. Classification. In International Encyclopedia of Communications; Barnouw, E., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989; Volume 1, pp. 292–296. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnott-Armstrong, W.; Wheatley, T. The Disunity of Morality and Why it Matters to Philosophy. Monist 2014, 95, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnap, R. Logical Foundations of Probability; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, P. Explication Defended. Studia Log. 2007, 86, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, T. (Ed.) Concept Formation in the Humanities and the Social Sciences; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, O. Solving the equity–equality conceptual dilemma: A new model for analysis of the educational process. Educ. Res. 2007, 49, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.-D. Fantastic educational gaps and where to find them: LERB–a model to classify inequity and inequality. J. Int. Educ. Pract. 2019, 2, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, W. The Sociology of Educational Inequality; Methuen: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Moravcsik, A. Transparency in Qualitative Research. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations; Atkinson, P., Delamont, S., Cernat, A., Sakshaug, J.W., Williams, R.A., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makel, M.C.; Plucker, J.A. Toward a More Perfect Psychology: Improving Trust, Accuracy, and Transparency in Research; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miguel, E.; Camerer, C.; Casey, K.; Cohen, J.; Esterling, K.M.; Gerber, A.; Glennerster, R.; Green, D.P.; Humphreys, M.; Imbens, G.; et al. Promoting Transparency in Social Science Research. Science 2014, 343, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cambridge Dictionary. Transparency; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, M.; Shahri, A.; Phalp, K.; Ali, R. Four reference models for transparency requirements in information systems. Requir. Eng. 2018, 23, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jordan, W.J. Defining Equity: Multiple Perspectives to Analyzing the Performance of Diverse Learners. Rev. Res. Educ. 2010, 34, 142–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, N. Descriptive Ethics: What Does Moral Philosophy Know about Morality; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp, R. (Ed.) Oxford Handbook of the History of Ethics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bottiani, J.H.; Bradshaw, C.P.; Mendelson, T. A multilevel examination of racial disparities in high school discipline: Black and white adolescents’ perceived equity, school belonging, and adjustment problems. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 109, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, E.K.; Rochmes, J.; Liu, J.; Solanki, S.M.; Loeb, S. Differing Views of Equity: How Prospective Educators Perceive Their Role in Closing Achievement Gaps. RSF: Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, L.C. Places for pluralism. Ethics 1992, 102, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, M. Moral Theory: An Introduction; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D. On meritocracy and equality. Public Interest 1972, 29, 29–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, U. How Schopenhauer’s ethics of compassion can contribute to today’s ethical debate. Enrahonar Quad. Filos. 2015, 55, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Handbook on Measuring Equity in Education; UNESCO Institute for Statistics: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018; p. 23. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/handbook-measuring-equity-education-2018-en.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Culyer, A.J. Equity—some theory and its policy implications. J. Med. Ethics 2001, 27, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kashwan, P.; MacLean, L.M.; García-López, G.A. Rethinking power and institutions in the shadows of neoliberalism: (An introduction to a special issue of World Development). World Dev. 2019, 120, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, S.J.; Papierno, P.B. The Rhetoric and Reality of Gap Closing: When the “Have-Nots” Gain but the “Haves” Gain Even More. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Omercajic, K.; Martino, W. Supporting transgender inclusion and gender diversity in schools: A critical policy analysis. Front. Sociol. 2020, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, C.; Peter, T. Every Class in Every School: Final Report on the First National Climate Survey on Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia in Canadian Schools; Egale Canada Human Rights Trust: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, D.M.; Ramirez, A.; Severn, L. Gap or Gaps:Challenging the Singular Definition of the Achievement Gap. Educ. Urban Soc. 2006, 39, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.D. Why We Need to Re-Think Race and Ethnicity in Educational Research. Educ. Res. 2003, 32, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.J. The Challenges of Achieving Equity Within Public School Gifted and Talented Programs. Gift. Child Q. 2021, 00169862211002535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefera, A.A.; Powers, J.M.; Fischman, G.E. Intersectionality in Education: A Conceptual Aspiration and Research Imperative. Rev. Res. Educ. 2018, 42, vii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borrell, L.N. Editorial: Critical race theory: Why should we care about applying it in our research? Ethn. Dis. 2018, 28, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLoughlin, G.M.; McCarthy, J.A.; McGuirt, J.T.; Singleton, C.R.; Dunn, C.G.; Gadhoke, P. Addressing Food Insecurity through a Health Equity Lens: A Case Study of Large Urban School Districts during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Urban Health 2020, 97, 759–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashiabi, G.S.; O’Neal, K.K. A Framework for Understanding the Association Between Food Insecurity and Children’s Developmental Outcomes. Child Dev. Perspect. 2008, 2, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faught, E.L.; Williams, P.L.; Willows, N.D.; Asbridge, M.; Veugelers, P.J. The association between food insecurity and academic achievement in Canadian school-aged children. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2778–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Winicki, J.; Jemison, K. Food Insecurity and Hunger in the Kindergarten Classroom: Its Effect on Learning and Growth. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2003, 21, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, J.; Baker, S. Refugees in Higher Education: Debate, Discourse and Practice; Emerald Group Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ro, H.K.; Fernandez, F.; Ramon, E.J. Gender Equity in STEM in Higher Education: International Perspectives on Policy, Institutional Culture, and Individual Choice; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel, H.B.; Sheehy-Skeffington, J.; Hauser, O.P.; Ho, A.K.; Kteily, N.S. Ideology selectively shapes attention to inequality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023985118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L.; Mayer, R. Development as the Aim of Education. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2012, 42, 449–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. International Standard Classification of Education. ISCED 2011; UNESCO Institute for Statistics: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, K.; Fararo, T. Purpose, Meaning, and Action: Control Systems Theories in Sociology; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, A.; Vallacher, R.R. Dynamical Social Psychology; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D.T. Control Theories in Sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2007, 33, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, R.; Pizarro, M.; Nevárez, A. The “New Racism” of K–12 Schools: Centering Critical Research on Racism. Rev. Res. Educ. 2017, 41, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Education Reform. Achievement Gap. Available online: https://www.edglossary.org/achievement-gap/ (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- Education Reform. Opportunity Gap. Available online: https://www.edglossary.org/opportunity-gap/ (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- Education Reform. Learning Gap. Available online: https://www.edglossary.org/learning-gap/ (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- Coleman, J.S.; Campbell, E.Q.; Hobson, C.J.; McPartland, J.; Mood, A.M.; Weinfeld, F.D.; York, R.L. Equality of Educational Opportunity (Report OE-38000); US Department of Health Education and Welfare, Office of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 1966.

- Francis, P.; Broughan, C.; Foster, C.; Wilson, C. Thinking critically about learning analytics, student outcomes, and equity of attainment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ziegler, A.; Kuo, C.-C.; Eu, S.-P.; Gläser-Zikuda, M.; Nuñez, M.; Yu, H.-P.; Harder, B. Equity Gaps in Education: Nine Points toward More Transparency. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 711. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110711

Ziegler A, Kuo C-C, Eu S-P, Gläser-Zikuda M, Nuñez M, Yu H-P, Harder B. Equity Gaps in Education: Nine Points toward More Transparency. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(11):711. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110711

Chicago/Turabian StyleZiegler, Albert, Ching-Chih Kuo, Sen-Peng Eu, Michaela Gläser-Zikuda, Miguelina Nuñez, Hsiao-Ping Yu, and Bettina Harder. 2021. "Equity Gaps in Education: Nine Points toward More Transparency" Education Sciences 11, no. 11: 711. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110711

APA StyleZiegler, A., Kuo, C.-C., Eu, S.-P., Gläser-Zikuda, M., Nuñez, M., Yu, H.-P., & Harder, B. (2021). Equity Gaps in Education: Nine Points toward More Transparency. Education Sciences, 11(11), 711. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110711