University Professor Training in Times of COVID-19: Analysis of Training Programs and Perception of Impact on Teaching Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Training of the University Professors

3. Impact of the Continuous Training of Professors

4. Methodology

4.1. Objectives

- To analyze the training received by professors from Catalan universities during the pandemic for their practice of teaching.

- To learn about the training proposals planned and the subjects that were most demanded.

- To evaluate the perception of impact of the training received.

4.2. Method

- First, a study was made of the continuous training offered to university professors in 2019 and 2020 by the different university units and institutions that were responsible for this matter. A comparison was made to determine the type of training proposals and the subjects developed, as well as to discover which garnered the most professors’ interest. The intention was to compare and contrast the differences between the training proposals from each year and, to verify if the new teaching reality due to the pandemic, intervened in the training demanded by the professors. This first phase was conducted through documentary analysis. The results are shown in a table of percentages.

- Second, through a non-experimental and descriptive quantitative research methodology, we constructed an ad hoc questionnaire to ask about aspects associated to the adequacy and perception of impact of the training received on the practice of teaching itself.

- Block 1: Type of training received (9 items),

- Block 2: Level of learning derived from the training (8 items),

- Block 3: Help from the knowledge acquired (12 items),

- Block 4: Feelings towards the use of the new knowledge (4 items),

- Block 5: Difficulties in the application of the training received (9 items), and

- Block 6: Perception of impact of the training (9 items).

- Descriptive tests of the quantitative variables with frequency and percentage tables.

- The Likert variables were described through a distribution of percentages of the responses and the habitual tools of means and standard deviations.

- The reliability of the questionnaires was assessed through Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient to measure the internal consistency. A value higher than 0.60 indicates an acceptable reliability, and, if higher than 0.80, it is good, or >0.90 very good.

- The non-parametric Friedman test was utilized to contrast the mean values of the Likert variables measured in the same sample of subjects that were not have a statistically normal distribution, to verify the meaning of the differences between them.

- To contrast the means of the subgroups of the different subjects, the Mann-Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were utilized when these were not distributed normally.

4.3. Sample

4.4. Validity and Reliability of the Questionnaire

5. Results

5.1. Training Proposals for University Professors at Catalan Universities

5.2. Description of the Perception of Impact of the Training Received on Teaching

5.2.1. Help from the Training Received

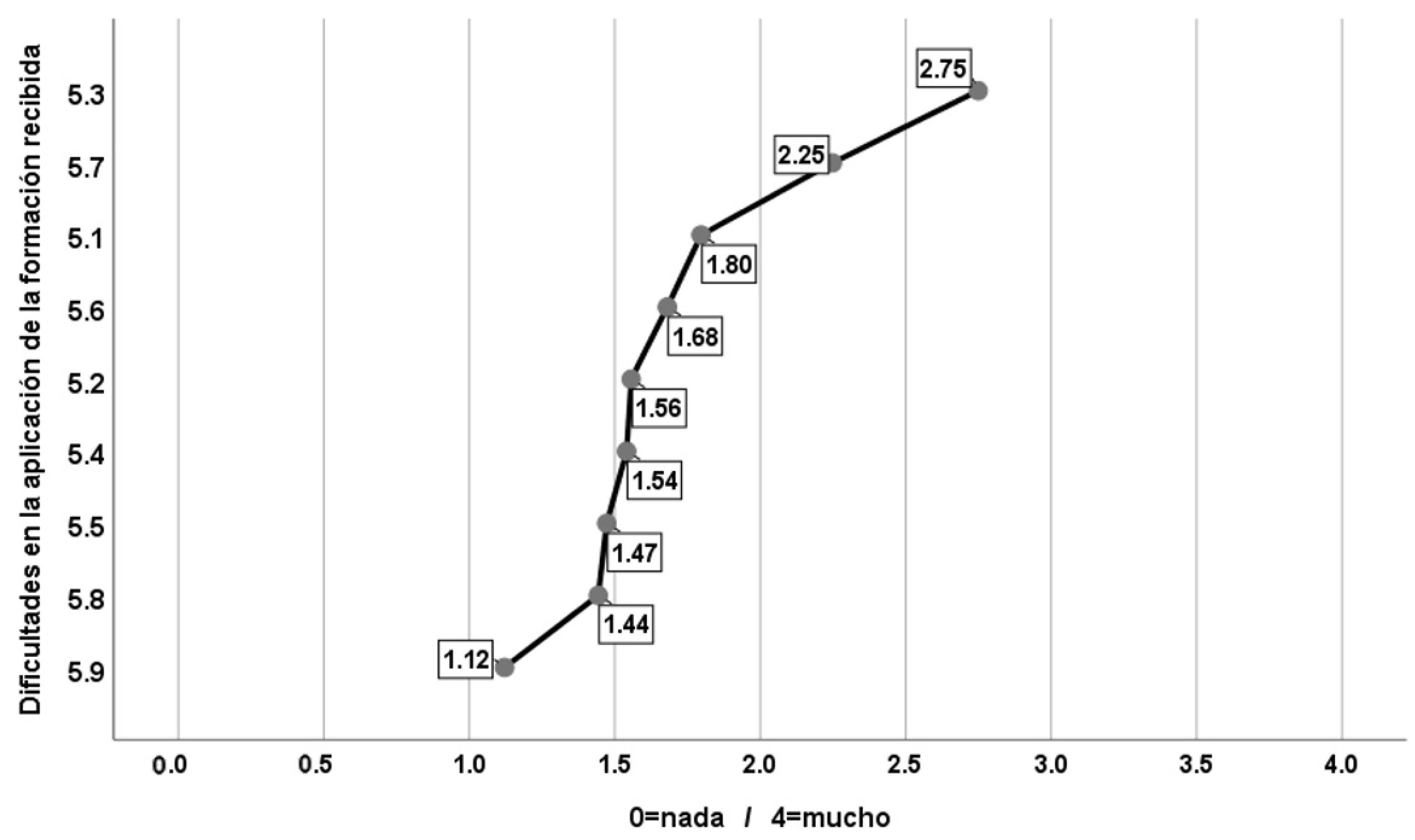

5.2.2. Block 5: Difficulties in the Application of the Training Received

5.2.3. Block 6: Perception of Impact of the Training

5.3. Inferential Analysis

- Gender: Differences were barely found with statistical significance and accompanied with an effect size of any importance. The ones that appeared indicated that:

- −

- Highest mean scores of women for the items: 3.6 (Develop new attitudes towards online teaching) and 6.5 (Application of new institutional digital resources).

- −

- Higher mean scores of men for items 5.3 (Lack of time) and 5.1 (Insufficient digital resources).

- Age: For the analysis of age as a possible explanatory factor for the differences between the items, many cut-off points for this variable were tried. Ultimately, the best results were found by the cut-off points presented in the following results: until 35 years old, from 36 to 50 years old, and from 51 years old forward. As a function of this categorization, high significances with a large effect size were found in:

- −

- In item 3.9 (Have more knowledge about online evaluations) (p < 0.001; effect of 6.6%) and item 6.4 (Application of new online evaluation strategies) (p < 0.001; effect of 6.7%), the highest mean was observed in the younger participants, with the lowest value found in the intermediate age group, to again increase in the oldest group.

- −

- In item 5.1 (Insufficient digital resources) (p < 0.001; effect of 6.1%), the inverse relationship can again be observed, where the score was reduced as the age of the participants increased, but especially in the jump from the 31 years old with respect to those who are younger.

- Knowledge: the highest means were observed in Arts and Humanities, and Social and Legal Sciences, with the lowest mean observed for Sciences. The significances with large effects were especially observed in Block 3, in the items: Improve my online teaching, improve the quality of my online teaching. Develop new aptitudes for online teaching, and Have more knowledge about quality online teaching. The Sciences professors scored this last item with the lowest values.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization: Coronavirus Disease. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 de Marzo, Por el Que se Declara el Estado de Alarma Para la Gestión de la Situación de Crisis Sanitaria Ocasionada por el COVID-19; Boletín Oficial del Estado, 67, de 14 de Marzo de 2020; Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 25390–25400.

- del Arco, I.; Flores, Ò.; Ramos-Pla, A. Structural model to determine the factors that affect the quality of emergency teaching, according to the perception of the student of the first university courses. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Arco, I.; Silva, P.; Flores, O. University Teaching in Times of Confinement: The Light and Shadows of Compulsory Online Learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zubayer, H.; Tahmina, S. University teachers’ training on online teaching-learning using online platform during COVID-19: A case Study. Bangladesh Educ. J. 2019, 18, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cabero-Almenara, J. Aprendiendo del tiempo de la COVID-19. Rev. Electrónica Educ. 2020, 24, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez Monzón, N. Formación docente universitaria y crisis sanitaria COVID-19. CienciAmerica 2020, 9, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, E.L. La formación docente del profesorado universitario: Sentido, contenido y modalidades. Bordón Rev. Pedagog. 2016, 68, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rowland, S.; Byron, C.; Furedi, F.; Padfield, N.; Smyth, T. Turning academics into teachers? Teach. High. Educ. 1998, 3, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res. 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejas-León, R. La Formación en TIC del Profesorado y su Transferencia a la Función Docente. Tendiendo Puentes Entre Tecnología, Pedagogía y Contenido Disciplinar. Ph.D. Thesis, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2018. Available online: https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/525864 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Vergara, C.; Cofré, H. Conocimiento Pedagógico del Contenido: ¿el paradigma perdido en la formación inicial y continua de profesores en Chile? Estud. Pedagógicos 2014, 40, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuartas, M.; Quintero, V. Formación docente en el desarrollo de competencias digitales e informacionales a través del modelo enriquecido Tpack*Cts*Abp. In Proceedings of the Congreso Iberoamericano de Ciencia, Tecnología, Innovación y Educación, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 14 November 2016; Available online: https://es.slideshare.net/maritzacts/784-tpackenriquecid (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Cejas-León, R.; Navío-Gámez, A.; Meza-Cano, J. Conexiones entre tecnología, pedagogía y contenido disciplinar (TPACK). La formación en TIC y su transferencia a la función docente. In Investigación en Docencia Universitaria. Diseñando el Futuro a Partir de la Innovación Educativa; Roig-Vila, R., Ed.; Octaedro Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2017; pp. 114–122. [Google Scholar]

- Cejas-León, R.; Gámez, A.N. Formación en TIC del profesorado universitario. Factores que influyen en la transferencia a la función docente. Profr. Rev. Currículum Form. Profr. 2018, 22, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paricio, J.; Fernández March, A.; Fernández Fernández, I. Marco de Desarrollo Académico Docente. Un Mapa de la Buena Docencia Universitaria Basado en la Investigación; REDU, Red de Docencia Universitaria: Bilbao, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- De Ketele, J.M. La formación didáctica y pedagógica de los profesores universitarios: Luces y sombras. Rev. Educ. 2003, 331, 143–169. [Google Scholar]

- Abella, V.; López Nozal, C.; Ortega, N.; Sánchez Ortega, P.L.; Lezcano, F. Implantación de UBUVirtual en la Universidad de Burgos: Evaluación y expectativas de uso. EDUTEC Rev. Electrónica Tecnol. Educ. 2011, 38, a184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomàs-Folch, M.; Duran-Benlloch, M. Comprendiendo los factores que afectan la transferencia de la formación permanente del profesorado. Propuestas de mejora. Rev. Electrón. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2017, 20, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abella, V.; Ausín, V.; Delgado, V.; Hortigüela, D.; Solano, H.J. Determinantes de la calidad, la satisfacción y el aprendizaje percibido de la e-formación del profesorado universitario. RMIE Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. 2018, 23, 733–760. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, T.T.; Ford, J.K. Transfer of training: A review and directions for the future research. Pers. Psychol. 1988, 41, 63–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buick, F.; Blackman, D.; Johnson, S. Enabling middle managers as change agents: Why organisational support needs to change. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2018, 77, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monereo, C. La investigación en la formación del profesorado universitario: Hacia una perspectiva integradora. Infanc. Aprendiz. 2013, 36, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osuna-Acevedo, S.; Marta-Lazo, C.; Frau-Meigs, D. De sMOOC a tMOOC, el aprendizaje hacia la transferencia profesional: El proyecto europeo ECO. Comunicar 2018, 55, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Medina, J.L.; Jarauta, B.; Urquizu, C. Evaluación del impacto de la formación del profesorado universitario novel: Un estudio cualitativo. RIE Rev. Investig. Educ. 2005, 23, 205–238. [Google Scholar]

- Cano García, E. Factores favorecedores y obstaculizadores de la transferencia de la formación del profesorado en Educación Superior. REICE Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2016, 14, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villalobos-Claveria, A.A.; Melo-Hermosilla, Y.M. Narrativas docentes como recursos para la comprensión de la transferencia didáctica del profesor universitario. Form. Univ. 2019, 12, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okoye, K.; Arrona-Palacios, A.; Camacho-Zuñiga, C.; Hammout, N.; Luttmann, E.; Escamilla, J.; Hosseini, S. Impact of students evaluation of teaching: A text analysis of the teachers qualities by gender. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020, 49, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feixas, M.; Lagos, P.; Fernández, I.; Sabaté, S. Modelos y tendencias n la investigación sobre efectividad, impacto y transferencia de la formación docente en educación superior. Educar 2015, 51, 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente, C. Aspectos fundamentales de la formación del profesorado en TIC. Pixel-Bit Rev. Medios Educ. 2008, 31, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Ò.; del Arco, I.; Silva, P. The flipped classroom model at the university: Analysis based on professors’ and students’ assessment in the educational field. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2016, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pineda, P. Auditoría de la Formación: Análisis de las Actividades Formativas Para la Mejora de la Realidad Empresarial; Ediciones Gestión: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. The new Meaning of Educational Change; Teacher College Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gairín, J. La evaluación del impacto en programas de formación. REICE Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2010, 8, 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Pla, A. Organizational and informal learning in educational centers. Rev. Educ. 2021, 392, 215–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle, D.E.; Wiersma, W.; Jurs, S.G. Applied Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dorrego, E. Educación a Distancia y Evaluación del Aprendizaje. RED Rev. Educ. Distancia 2016, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzman, G.; Roni, C.; Berk, M.; Delorenzi, E.; Sánchez, M.; Eder, M.L. Evaluación Remota de Aprendizajes en la Universidad: Decisiones docentes para encarar un nuevo desafío. RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2021, 24, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero-Almenara, J.; Palacios-Rodríguez, A. La evaluación de la educación virtual: Las e-actividades. RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2021, 24, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, R. La aflicción de la docencia y el tiempo del enseñante. Razón Palabra 2012, 79, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tomàs-Folch, M.; Castro Ceacero, D.; Feixas Condom, M. Tensiones entre las funciones docente e investigadora del profesorado en la universidad. REDU Rev. Docencia Univ. 2012, 10, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramos-Pla, A.; Camats, R. Consideraciones generales respecto a la necesidad de practicar una pedagogía sobre la finitud humana en la educación formal. Estudio de caso. Educar 2019, 55, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Arco, I.; Flores, Ò.; Guitard, M.L.; Saltó, E.; Ramos-Pla, A.; Massey, W.; Llebaria, X.; Silva, P.; Jover, A.; Barcenilla, F.; et al. En las organizaciones saludables y sostenibles. El empoderamiento individual como nuevo paradigma en la gestión del conocimiento. In La Nueva Gestión del Conocimiento, 1st ed.; Gairín, J., Suárez, C.I., Díaz-Vicario, A., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 473–519. [Google Scholar]

- del Arco, I.; Ramos-Pla, A.; Flores, Ò. Analysis of the Company of Adults and the Interactions during School Recess: The COVID-19 Effect at Primary Schools. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Training Content | Percentage 2019 | Percentage 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional digital tools | 32.25% | 36.23% |

| Non-institutional digital tools | 21.78% | 9.67% |

| Methodologies compatible with online teaching | 20.16% | 13.04% |

| Communication through digital tools | 2.42% | 3.86% |

| Evaluation compatible with online teaching | 5.65% | 13.53% |

| Personal management in times of crisis | 1.61% | 0.97% |

| Equipment for hybrid classrooms | 0.81% | 0.97% |

| Design of online courses: transition to remote teaching | 4.03% | 12.56% |

| Tutoring | 4.03% | 2.42% |

| Computer safety and data protection | 4.03% | 6.76% |

| Total for online teaching training | 18.51% | 30% |

| % of Response for Each Option | Descriptive Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | Std. Dev. |

| 3.1: Improve my online teaching | 3.2 | 6.6 | 12.9 | 43.3 | 34.0 | 2.98 | 1.01 |

| 3.2: Be more efficient in online teaching | 3.2 | 8.2 | 16.9 | 40.1 | 31.7 | 2.89 | 1.04 |

| 3.3: Improve the quality of my online teaching | 3.2 | 8.2 | 23.2 | 37.7 | 27.7 | 2.79 | 1.04 |

| 3.4: Become more aware of my needs | 7.1 | 5.5 | 21.1 | 28.0 | 38.3 | 2.85 | 1.20 |

| 3.5: Have more interest for learning about online teaching | 8.7 | 11.1 | 20.3 | 30.6 | 29.3 | 2.61 | 1.25 |

| 3.6: Develop new aptitudes for online teaching | 4.7 | 7.1 | 22.2 | 39.6 | 26.4 | 2.76 | 1.07 |

| 3.7: Have more knowledge about methodologies that are adequate for online teaching | 7.1 | 7.9 | 23.5 | 36.1 | 25.3 | 2.65 | 1.15 |

| 3.8: Have more knowledge about digital tools | 4.0 | 4.0 | 15.3 | 42.0 | 34.8 | 3.00 | 1.01 |

| 3.9: Have more knowledge about online evaluations | 11.1 | 12.1 | 19.3 | 26.9 | 20.6 | 2.44 | 1.25 |

| 3.10: Have more knowledge about quality online teaching | 8.7 | 9.5 | 22.7 | 36.9 | 22.2 | 2.54 | 1.19 |

| 3.11: Have more tools to improve communication | 10.3 | 13.7 | 20.1 | 33.8 | 22.2 | 2.44 | 1.26 |

| 3.12: Establish collaboration and exchange networks with other colleagues | 24.5 | 21.4 | 27.7 | 13.5 | 12.9 | 1.69 | 1.32 |

| Percentage of Response for Each Option | Descriptive Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | Std. Dev. |

| 5.1: Insufficient digital resources | 24.8 | 19.6 | 20.1 | 24.0 | 12.1 | 1.80 | 1.37 |

| 5.2: Insufficient training on online teaching | 24.8 | 25.6 | 25.9 | 16.6 | 7.1 | 1.56 | 1.23 |

| 5.3: Lack of time | 7.1 | 103 | 20.1 | 25.6 | 36.9 | 2.75 | 1.25 |

| 5.4: Lack of support from the institution | 31.9 | 19.8 | 23.5 | 11.9 | 12.9 | 1.54 | 1.38 |

| 5.5: Insecurity in implementing new things | 25.6 | 27.2 | 26.1 | 16.6 | 4.5 | 1.47 | 1.70 |

| 5.6: Difficulty in applying new methodologies | 19.0 | 24.0 | 30.3 | 23.2 | 3.4 | 1.68 | 1.13 |

| 5.7: Difficulty in applying the evaluation compatible with online teaching | 13.5 | 16.6 | 24.5 | 22.4 | 23.0 | 2.25 | 1.34 |

| 5.8: Difficulty in applying digital resources | 22.2 | 32.7 | 26.4 | 16.1 | 2.6 | 1.44 | 1.08 |

| 5.9: Lack of access to technological means and resources | 45.4 | 15.8 | 22.7 | 13.5 | 2.6 | 1.12 | 1.20 |

| Percentage of Response for Each Option | Descriptive Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | Std. Dev. |

| 6.1: Development of my digital competence | 3.2 | 4.7 | 17.7 | 41.2 | 33.2 | 2.97 | 0.99 |

| 6.2: Application of the knowledge acquired | 1.6 | 1.6 | 16.9 | 39.3 | 40.6 | 3.16 | 0.87 |

| 6.3: Application of new technologies | 2.4 | 8.2 | 21.4 | 34.6 | 33.5 | 2.89 | 1.04 |

| 6.4: Application of new online evaluation strategies | 7.7 | 15.8 | 23.0 | 29.0 | 24.5 | 2.47 | 1.23 |

| 6.5: Application of new institutional digital resources | 2.4 | 8.2 | 15.3 | 30.3 | 43.8 | 3.05 | 1.06 |

| 6.6: Application of new non-institutional digital resources | 19.3 | 7.1 | 25.9 | 25.6 | 22.2 | 2.24 | 1.39 |

| 6.7: Use of new ways to communicate with the student | 5.8 | 7.9 | 25.3 | 30.9 | 30.1 | 2.72 | 1.15 |

| 6.8: Maintenance of the same teaching format | 23.7 | 26.1 | 25.3 | 20.1 | 4.7 | 1.56 | 1.19 |

| 6.9: Creation of a network of colleagues to share experiences | 43.0 | 29.0 | 15.3 | 9.6 | 3.2 | 1.01 | 1.12 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos-Pla, A.; del Arco, I.; Flores Alarcia, Ò. University Professor Training in Times of COVID-19: Analysis of Training Programs and Perception of Impact on Teaching Practices. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110684

Ramos-Pla A, del Arco I, Flores Alarcia Ò. University Professor Training in Times of COVID-19: Analysis of Training Programs and Perception of Impact on Teaching Practices. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(11):684. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110684

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos-Pla, Anabel, Isabel del Arco, and Òscar Flores Alarcia. 2021. "University Professor Training in Times of COVID-19: Analysis of Training Programs and Perception of Impact on Teaching Practices" Education Sciences 11, no. 11: 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110684

APA StyleRamos-Pla, A., del Arco, I., & Flores Alarcia, Ò. (2021). University Professor Training in Times of COVID-19: Analysis of Training Programs and Perception of Impact on Teaching Practices. Education Sciences, 11(11), 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110684