The results of this study would be presented under the light of the two following research questions.

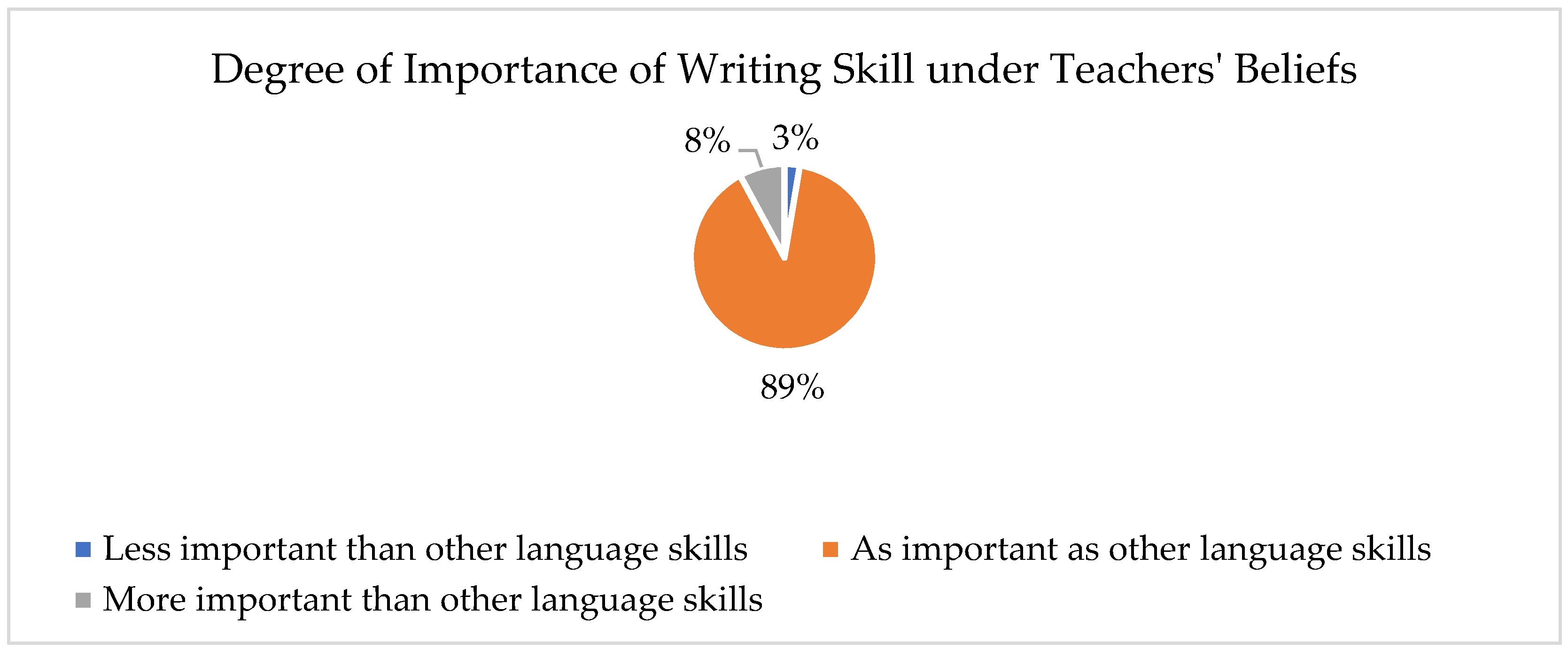

Research question 1: What are the teachers’ beliefs in teaching writing skills, including the importance of writing skills, merits and nature of writing, teachers’ roles, and teaching activities?

In order to respond to the first research questions, the researchers analyzed and categorized the data into themes.

3.2. Beliefs in Teachers’ Roles

On the one hand, the teachers widely favored the role of a knowledge transmitter to the highest extent (Item 7, M = 4.47, SD = 0.621). This is in line with what Nguyen [

54] suggests when discussing teaching EFL writing in the Vietnamese context: “language teachers need to provide learners with certain input before asking them to write.” She further explains, “input drives acquisition, which should be put ahead of teaching in any approach of language instruction that wants to be successful.” Accordingly, the researcher thinks that direct knowledge transmission or comprehensive input (e.g., grammatical items, key expressions, text structures) when teaching writing is essential, especially for high school students. However, suppose that so much of the work of learning is controlled and directed by the teacher. In that case, students may confront some difficulties in free writing, which has received more attention in recent new-format examinations.

On the other hand,

Table 2 reveals that these high school teachers did not seem to believe in the effectiveness of the main teacher role as a facilitator in their current writing classroom (Item 8, M = 3.18, SD = 1.092). This ignorance may be explained that in order to fulfill this role successfully, the teachers are required to conduct several challenging learner-centered tasks; for example, organizing students to do various writing activities [

41]; provoking the students into having ideas when they get stuck [

29]; organizing writing activities collaboratively through the use of pair or group work [

44]; and creating a favorable environment for students to write a lot [

22]. However, if successfully fulfilling in the context of high schools, facilitators can motivate students to learn writing, enhance learner autonomy [

41]; as a result, their writing ability can be independently developed. Nevertheless, without language input provided by knowledge transmitters, these students could hardly learn this productive skill effectively due to such a minimal curriculum, consisting of sixteen classes and forty-five minutes per class.

Given such a situation mentioned above that each separate role has its negative effect, the respondents strongly believed that a combination of these two roles mentioned above could manifest their high school students’ writing ability as much as possible (Item 9, M = 4.39, SD = 0.655). To elaborate, flexibility in teacher roles may lead students to acquire language input sufficiently provided by teachers and produce writing output meaningfully and independently by themselves. Clearly, in terms of teacher roles, the participants preferred Chai’s [

28] perspectives, i.e., knowledge transmission and construction, in a combined way.

3.3. Beliefs in Teaching

Teaching writing is an act of different steps or procedures, involving (a) the choice of instructional activities, (b) the selection and employment of instructional materials, (c) the choice of corrective feedback, and (d) the encouragement of students’ extensive practice. Accordingly, teachers’ beliefs about teaching writing may involve these dimensions. From the data in

Table 3, it is apparent that the selected participants strongly held their beliefs about form-based orientation in teaching writing for high school students (Item 10, M = 4.54, SD = 0.621) through teachers analyzing model texts on the basis of linguistic features and genre schematic structures before students writing. Positively, functional social-based orientation to teaching writing was highly appreciated by the respondents (Item 11, M= 4.21, SD = 0.805) when they thought that teachers should raise students’ awareness of the social function and purpose of the text (e.g., narrating, reporting, etc.). Obviously, the high school teachers still followed traditional beliefs, that is, the knowledge transmission view. The researchers agreed that providing the sample texts and developing students’ understanding of the social functions of these texts should be first practiced in writing instruction for many low-level high school students. In addition to the aforementioned stable beliefs on the choice of form-based and functional social-based orientations to teaching writing at the high schools, the teachers were united in their belief that they should guide students in how to compose a text independently (Item 12, M= 3.89, SD = 0.798) as well as organize collaborative activities among students in pairs/groups (Item 13, M = 3.74, SD = 1.063). Personally, the researchers posited that the teachers need to give their students an understanding of the steps to manipulate their writing so that they become independent writers in different situations, even in examinations. At the same time, interaction that is built up among students during writing classes can bring out considerable lucrative outcomes; for example, if students are encouraged to participate in the activities of meaning exchange with their peers in learning writing, it can help student writers have positive reinforcements about the knowledge of linguistics, content, and ideas in composing texts [

55]. Thus, the participating teachers had multiple orientations to teaching writing at their high schools. Simply, the Vietnamese teachers relied on a combination of product, process, and genre-based approaches in their writing instruction. Nevertheless, the teachers’ pedagogical beliefs about instructional activities mostly followed the view of knowledge transmission rather than that of knowledge construction. Ultimately, using different orientations to teaching writing skills is necessarily essential in the high school context since, according to what Uddin [

22] recommends, “teachers need orientation regarding different approaches to teaching writing other than what they follow along with a practical demonstration on how each approach functions” (p. 125).

Another component of teachers’ pedagogical beliefs is the selection and employment of instructional materials, which are an indispensable part of the teaching process [

56]. According to Nguyen [

53], the activities in “

D. Writing” sections in the textbook series mandated by the Vietnamese MOET do not target readership and writing purposes. Thus, it should be necessary to utilize authentic materials that have been produced to fulfill some social purposes in the language community [

57]. Expectedly, most teachers positively believed that they should use authentic supplementary materials such as newspaper articles, letters, and videos besides the prescribed textbooks for their writing class (Item 14, M = 4.54, SD = 0.720). This belief was in agreement with the prescription of the Vietnamese MOET that “…teachers employ supplementary materials to motivate students” (p. 7). If a teacher uses suitable authentic materials in the language classroom, it motivates students because these are more interesting and inspiring than artificial materials. In fact, using authentic materials in writing instruction brings about some considerable benefits. First, these real-life materials motivate students to learn to write much when they are exposed to interesting teaching resources such as audio, visual, and printed materials [

57]. Furthermore, since these resources are designed for real-life use for interactional and transactional purposes [

33], it is believed that these genuine materials can help students develop an understanding of the social function and communicative purpose of the text to be written effectively, which is based on the view of writing as functional social-based activity. Thereby, high school teachers should be encouraged to employ authentic materials and textbooks to help their students yield much improvement in their writing ability, including motivation and social awareness of writing text.

It is said that practice makes perfect. In other words, it is important that teachers should establish several chances for their high school students to practice writing much more. Teachers could hardly offer enough chances for their students to practice writing inside the classroom [

47]. Thus, Uddin [

22] argues that students should be required to be engaged in out-of-class writing activities, since the steps of the writing process could not be fully accomplished inside the classroom. Positively, the data in

Table 3 reveal that the participants widely agreed that they should create a favorable environment for students to write a lot (Item 15, M = 4.49, SD = 0.774) so that students could manipulate the stages of the writing process such as idea brainstorming, idea organizing, and appropriate linguistic selecting by themselves. Succinctly stated, assigning students to practice writing on a similar topic and text types outside the classroom is an ideal way, as “practice makes perfect.” Especially, the cognitive processes through writing activity can be much more practiced in a comfortable way, as the steps of the writing process could not be entirely accomplished inside the classroom where there exists a temporal limit and a rigid curriculum.

Often happening during or after students writing, the provision of correct feedback by the teachers is an indispensable component of the teaching process, contributing to students’ writing development. There are two orientations to providing corrective feedback [

49], including form accuracy and content fluency. It is apparent from the above table that to help students enhance their writing ability, the majority of the teacher participants strongly believed that providing corrective feedback on both language use and idea development is the most optimum way (Item 18, M = 4.34, SD = 0.758). However, the participating teachers preferred providing corrective feedback on students’ language use (Item 16, M = 4.03, SD = 0.838) to their idea development (Item 17, M = 3.45, SD = 0.855). To some extent, it seems that the teachers still favored form-based orientation rather than a meaning-making process-based one, even in the act of providing written feedback. The teachers’ belief in providing written feedback was consistent with their beliefs about the importance of writing toward high school students mentioned earlier. Specifically, writing was believed to be helpful for students to increase vocabulary scope as well as improve their spelling and grammar rather than practice gathering and organizing ideas. Nevertheless, the teachers’ belief about a combination of both form-based and meaning-making process-based orientations for their providing corrective feedback was ultimately found. To recap, it is essential for the teachers to suggest their corrective feedback on the overall quality of students’ writing because writing ability refers to accurate language use and fluent idea development. In other words, when correcting students’ writing, the teachers should focus on both sentential and textual levels.

The following section presents the results of the second research question.

Research question 2: What are the teachers’ real writing practices in their classrooms in terms of pre-writing activities, while-writing activities, and post-writing activities?

To provide answers to this research question, all the teachers’ classrooms practices, including pre-writing activities, while writing activities, and post-writing activities were analyzed.

3.4. Teachers’ Classroom Practices

3.4.1. Pre-Writing Phase

As can be seen from

Table 4, the teacher participants usually provided their students with a sample text of writing (Item 19, M = 3.91, SD = 0.751) before they were asked to write their own texts. This act was consistent with what Nguyen [

54] posits: that language teachers need to provide learners with certain input before asking them to write. However, this model writing text was much more frequently extracted from the textbooks (Item 20, M = 4.01, SD = 0.902) rather than from authentic supplementary materials (Item 21, M = 2.59, SD = 0.824). As discussed earlier, authentic materials play a pivotal role in building students’ awareness of social functions and contexts of what to be written; therefore, the teachers should be encouraged to employ these kinds of materials for their teaching.

After introducing the model writing text, the respondents usually highlighted its linguistic features (e.g., vocabulary, grammar) and genre schematic structure (e.g., parts of a particular text type) (Item 23, M = 4.10, SD = 0.778) as well as often had them do a few controlled exercises of these highlighted linguistic features and genre schematic structure such as filling in, matching, ordering, etc. (Item 24, M = 3.69, SD = 0.775). A positive finding was ultimately found that the teachers usually utilized a set of comprehension questions in order for students to capture the function and context of the model text, such as “What is the text about? Who wrote it and who will read it? What the text is written for?” (Item 22, M = 3.88, SD = 0.753) It is interpreted that the teachers were much or less focused on the functional social-based nature of writing.

However, it is apparent from this table that the majority of the participants did not often, if any, have their high school students brainstorm to generate ideas before their writing individually (Item 26, M = 2.52, SD = 0.828) as well as in pairs or groups (Item 27, M = 2.34, SD = 0.873). In theory, brainstorming before starting to write is extremely important when it helps student writers grasp what is to be written by themselves; on the contrary, in practice, this activity seems to be neglected.

To sum up, for the pre-writing activities, many of the respondents usually offered a writing model text for their students to study first. The teachers subsequently provided an analysis of the model text in terms of its linguistic forms and genre forms. Then, these forms were practiced and manipulated through students carrying out a couple of controlled exercises. Clearly, the form-based orientation to teaching writing was followed in the pre-writing phase. Regardless of whether intentionally or not, the functional social-based orientation to teaching writing was ultimately applied in which many teachers asked their students a set of comprehension questions in terms of its social context and communicative functions when the model text was learned. Yet, it is really effective to construct students’ social and functional awareness of what to be written when authentic materials are more frequently employed in their writing classroom. This request originally stems from the reality that these lively materials have not had their place in writing classrooms at the selected high schools so far. Noticeably, idea brainstorming in individuals or pairs/groups, one of the writing steps, was not much practiced, if any. Put simply, cognitive process-based and interactive social-based orientations seem to be abandoned in this phase.

3.4.2. During-Writing Phase

As

Table 5 indicates, the majority of the teachers, after pre-writing activities, usually had their students manipulate the linguistic features (e.g., vocabulary, grammar) and the genre schematic structures (e.g., the distinct parts of a particular text type) as well as the prompts suggested by the textbooks or teachers to construct their freer text (Item 25, M = 3.86, SD = 1.055). Apart from what is called freewriting, this was still somehow controlled composition tasks. Rather surprisingly, many of the participants revealed that during students’ writing, they sometimes moved around their classrooms, helping their students when they got stuck in terms of either language use or ideas (Item 32, M = 3.28, SD = 0.918). Indeed, this kind of interaction between the teachers and their students should be adequately expanded in writing classrooms in which the students are still independent writers while the teachers take an active role as facilitators.

On the contrary, a set of cognitive process-based activities (e.g., outlining, drafting, revising, and so forth) were not actually practiced in writing classrooms at the high schools for this phase. Specifically, not many teachers had their students organize their ideas based on the just-introduced genre schematic structure (Item 28, M = 2.97, SD = 0.776). In other words, the outlining step of the writing process was not much favored by the majority of these teachers in practice. To further elaborate, the low frequency of this activity can stem from the fact that the brainstorming step was not practiced beforehand in the pre-writing phase; moreover, the responses to the writing topics are usually available in the textbooks. It seems apparent that the high school teachers did not frequently have their students write multiple drafts (Item 29, M = 2.93, SD = 0.718) before composing the final product. In addition, this table also reveals that peer feedback among student writers, one of the factors contributing to their writing development, was not practically employed by the greater part of teachers (Item 30, M = 2.55, SD = 0.855). Accordingly, it is clearly found that most of the participating teachers did not lead the students to revise their own texts, which was based on feedback from the teachers and classmates (Item 31, M = 2.63, SD = 0.712).

In closing, most of the recruited teachers still followed the form-based orientation to teaching writing in this central phase during writing activities. It is proved that the teachers frequently asked their students to manipulate the learned linguistic and genre forms to write their own texts in a freer way. On the contrary, there seems to be no explicit emphasis on the process of outlining, drafting, peer feedback, and revision. Put differently, the cognitive process-based and social-based orientations were not practically applied in their writing classrooms. However, the most striking result of this phase was that the teachers sometimes interacted with their students by helping them with language and idea resources.

3.4.3. Post-Writing Phase

Table 6 shows that a greater number of the participants only sometimes gave corrective feedback and evaluated their students’ writing inside classrooms (Item 33, M = 3.04, SD = 0.936). The limited frequency of this activity may be easily understood because inviting a couple of students to write their work on the blackboard was really time consuming within such a rigid schooling curriculum in the high school contexts. This was consistent with Corpuz’s [

19] concern that providing written error correction helps students improve their proofreading skills in order to revise their writing more efficiently but is very time consuming. Therefore, it is unsurprising that most of the participants usually asked their students to complete their own texts into notebooks at home due to time constraints (Item 37, M = 4.07, SD = 0.838). Contrary to expectations, most teachers did not frequently create many opportunities for their students to practice writing in a comfortable way, such as assigning another similar topic to their students after each writing class (Item 38, M = 2.64, SD = 0.778). Essentially, the teachers should let students develop their own writing ability independently in a favorable environment such as at home. This originally emerges from the fact that the basic steps of the writing process were only introduced inside classrooms if any, and not much practiced. Thereby, within an exciting writing topic assigned to homework, it is believed that many high school students can experience some basic writing sub-skills such as gathering appropriate language and ideas, outlining their gathered ideas, drafting and revising, and so on. In other words, practice makes perfect regardless of any schooling level.

Furthermore, the orientations to giving corrective feedback on students’ writing were also obviously pointed out. In practice, the majority of the participating teachers preferably responded to their students’ writing on the basis of accurate language use (Item 34, M = 3.92, SD = 0.774). Conversely, corrective feedback on the students’ fluent idea development was not favorably practiced by many of the respondents (Item 35, M = 3.25, SD = 0.926). It goes without saying that in the reality of providing their written feedback, almost all of the teachers still concentrated on form-based orientation rather than a meaning-making process-based one. In comparison, this practice was somewhat consistent with the teachers’ perceptions about the importance of writing toward high school students. Rather positively, many of the high school teachers in this study revealed that they also usually responded to their students’ writing in terms of overall quality (Item 36, M = 3.79, SD = 0.943); however, language accuracy was still prioritized above idea fluency so far (Mlanguage accuracy = 3.92; Midea fluency = 3.25) in practice.

To recap, in the after-writing phase, the teachers sometimes corrected and evaluated their students’ writing (e.g., between one and two students) before ending the writing lessons, in which accurate language forms were preferably the focus rather than idea organization. For an out-of-class writing activity, a greater number of the participants usually had their students finish their texts into notebooks instead of assigning them another similar topic for further writing practice.

The next section presents the results of the third research question, which is the main focus of the current study.

Research question 3: Are there any differences between the teachers’ writing instruction beliefs and their classroom practices?

The data to respond to the third research question were included the form-based orientation, process-based orientation, and functional and interactive social-based orientation.

3.5. The Alignment between Beliefs and Classroom Practices

Whether the classroom instructional practices of the high school teachers in writing classes were congruent with their beliefs became another inquiry of the paper, which was pertinent to the four orientations or natures of writing with three inferential scale intervals: 1.00–2.60: Low degree, 2.61–3.40: Medium degree, 3.41–5.00: High degree.

As

Table 7 illustrates, the form-based beliefs held by most participating teachers were nearly aligned with their practices. Alternatively saying, the product approach was much prevalent in their EFL writing instructional practices at their high schools.

From

Table 7 below, although a large number of the teachers positively believed in the lucrative outcomes of a process-based orientation, there were some tensions between what the teachers believed and what the teachers did. In practice, brainstorming, improvement, or extensive writing were discouraged too much, which was caused by multiple factors such as class duration, students’ perceived lack of motivation, and teaching materials.

Based on the data presented in

Table 7, the functional social-based nature of writing also received high appreciation from a greater part of teacher participants, i.e., the necessity of raising students’ awareness of social functions and communicative purposes of what to be written, and of using authentic supplementary materials. However, this belief was not always aligned with what the high school teachers actually did; that is, the model texts were only extracted from the textbooks so far, which was due to the teachers’ preparation time and the students’ existing proficiency level.

As evidenced in

Table 7, the interactive social nature of writing was eventually accepted in the teachers’ rooted beliefs, but in practice, this orientation seemed not to be enacted in their writing classrooms: for example, there was a low density of student–student interactions. Multiple factors accounted for this lack of congruence between the teachers’ beliefs and practices, which were inclusive of class duration and teaching materials’ requirement.

Laconically, Item 39 synthesized the possible impacting factors on the relationship between the studied teachers’ beliefs and actual classroom practices of EFL writing instruction at their high schools.

As can be shown in

Figure 4, the study suggested that the complexities of classroom life could have powerful influences on teachers’ beliefs and affect their classroom practices. Several possibilities could explain the mismatch between teachers’ beliefs and their actual practices, in which the most influencing factors derived from contextual factors such as students’ knowledge and English level (91%), examination demands (90%), students’ perceived lack of motivation to write (84%), and teachers’ preparation time (79%). In addition, class duration (86%), curricular (84%), and teaching materials (74%) were also direct causal factors leading to mismatches between what the teachers believed and what they practically did in the domain of teaching writing at their high school contexts.