The Designing and Re-Designing of a Blended University Course Based on the Trialogical Learning Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

The Trialogical Learning Approach

3. The Research

3.1. Objectives

- RQ1: What is the impact of the course on students’ perceptions of their development of specific knowledge–work skills?

- RQ2: Which strengths and area of improvements do the students find in the course?

3.2. Method

3.2.1. Data Collection

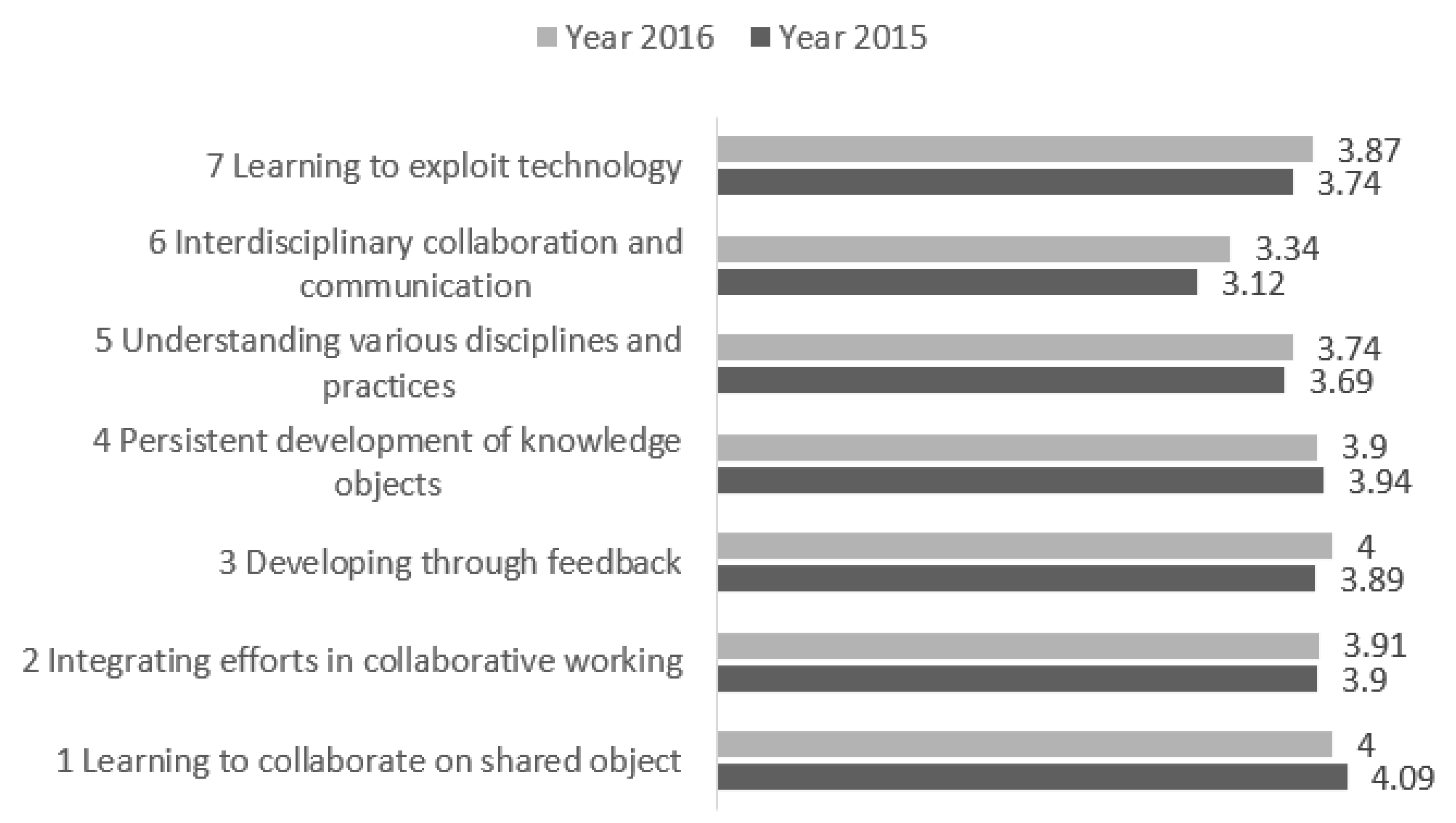

- Contextual Knowledge Practice questionnaire (CKP-q), completed anonymously at the end of the course. The questionnaire comprised 27 Likert-scale items that interrogated students’ perceptions of the extent to which they developed specific knowledge–work skills (1, not at all; 5, very much). The items were organized in seven scales built around the TLA design principles [18]: (1) collaborate on shared objects (DP1); (2) integrate individual and collaborative work (DP2); (3) development through feedback (DP3 and DP4); (4) persistent development of knowledge object (DP4); (5) understanding various disciplines and practices (DP5); (6) interdisciplinary collaboration and communication (DP5); and (7) learning to exploit technology (DP6). Students were asked to declare to what extent (1, not at all; 5, very much) they perceived themselves to have acquired the related skills at the end of the course (RQ1).

- Focus Groups (FG) held at the end of the first two iterations of the course to facilitate critical discussion around the course that had just ended (RQ2). Semi-structured interviews were used to elicit students’ views on: (1) the most valuable activity of the course; (2) the adopted learning strategies; (3) pros and cons of group work; (4) the course organization; and (5) the role of technologies. FGs were conducted by external moderators in order to promote students’ spontaneous and open comments.

3.2.2. Data Analysis

3.3. The TLA-Based Course Design

- Mixing of a variety of teaching strategies and methodologies;

- Flexible integration of digital tools;

- Cross-fertilization between the university context and the professional/external context.

4. Results

4.1. First Iteration

4.2. Second Iteration

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The design was strongly anchored to a theoretical model as well as structured and formalized through templates of pedagogical scenarios, yet left teachers able to personalize the design principles’ declinations;

- Each course iteration was progressively and gradually developed based on the results, and the re-design also included the revision of the Impact Analysis Instruments;

- Theoretical reflection continued to accompany all subsequent iterations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ritella, G.; Sansone, N. COVID-19: Turning a huge challenge into an opportunity. QWERTY J. 2020, 15, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J.B. Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 2nd ed.; Open University Press/Society for Research into Higher Education: Buckingham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Delors, J. Nell’Educazione un Tesoro, Trad; Coccia, E., Ed.; Armando Editore: Rome, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, S. Blended learning solutions. In Encyclopedia of Educational Technology; Hoffman, B., Ed.; 2005; Available online: http://coe.sdsu.edu/eet/articles/blendedlearning/start.htm (accessed on 10 January 2008).

- Bonk, C.J.; Graham, C.R. (Eds.) The Handbook of Blended Learning: Global Perspectives, Local Designs; Pfeiffer Publishing: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ligorio, M.B.; Amenduni, F.; Sansone, N.; Mclay, K. Designing blended university courses for transaction from academic learning to professional competences. In Cultural Views on Online Learning in Higher Education; Di Gesú, M.G., Gonzalez, M.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 13, pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ligorio, M.B.; Sansone, N. Structure of a Blended University Course: Applying Constructivist Principles to Blended Teaching. In Information Technology and Constructivism in Higher Education: Progressive Learning Frameworks; Payne, C.R., Ed.; Igi Idea Group Inc.: Hershey, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 216–230. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, N.; Cesareni, D.; Bortolotti, I.; Buglass, S. Teaching technology-mediated collaborative learning for trainee teachers. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2019, 28, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pozzi, F.; Persico, D. Sustaining learning design and pedagogical planning in CSCL. Res. Learn. Technol. 2013, 21, 17585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hakkarainen, K. Three generations of technology-enhanced learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2009, 40, 40–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavola, S.; Hakkarainen, K. The knowledge creation metaphor—An emergent epistemological approach to learning. Sci. Educ. 2005, 14, 535–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfard, A. On two metaphors for learning and the dangers of choosing just one. Educ. Res. 1998, 27, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilomäki, L.; Lakkala, M.; Kosonen, K. Mapping the terrain of modern knowledge work competencies. In Proceedings of the 15th Biennial Conference of the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction, University of Nicosia, Munich, Germany, 27–31 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, N.; Cesareni, D.; Ligorio, M.B.; Bortolotti, I.; Buglass, S.L. Developing knowledge work skills in a university course. Res. Pap. Educ. 2019, 35, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligorio, M.B.; Andriessen, J.; Baker, M.; Knoller, N.; Tateo, L. Talking over the Computer: Pedagogical Scenarios to Blend Computer and Face to Face Interaction; Scriptaweb: Naples, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Design-Based Research Collective. Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry. Educ. Res. 2003, 32, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Akker, J. Principles and methods of development research. In Design Methodology and Developmental Research in Education and Training; van den Akker, J., Nieveen, N., Branch, R.M., Gustafson, K.L., Plomp, T., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Muukkonen, H.; Lakkala, M.; Toom, A.; Ilomäki, L. Assessment of competences in knowledge work and object-bound collaboration during higher education courses. In Higher Education Transitions: Theory and Research; Kyndt, E., Donche, V., Trigwell, K., Lindblom-Ylänne, S., Eds.; EARLI Book Series New Perspectives on Learning and, Instruction; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 288–305. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Margolies, P.; Covell, N.; Lipscomb, C.; Dixon, L. Using Instructional Design, Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate, to Develop e-Learning Modules to Disseminate Supported Employment for Community Behavioral Health Treatment Programs in New York State. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lyon, A.R.; Stirman, S.W.; Kerns, S.E.U.; Bruns, E.J. Developing the mental health workforce: Review and application of training approaches from multiple disciplines. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| The Design Principle | How to Apply Them |

|---|---|

| DP1 Organize activities around shared objects | Didactic activities must converge towards the collaborative construction of artifacts:designed for real uses, thus acting as a bridge between formal learning contexts and workplace contexts, embodying the skills that learners need to acquire. |

| DP2 Supporting integration of personal and collective agency and work | It is necessary to combine individual and group:promoting individual and collective responsibility and motivation, encouraging the development of relational skills. |

| DP3 Fostering long-term processes of knowledge advancement | The learning situation should be lengthy enough to allow: the iteration of different cycles of the same activities an advancement of knowledge when moving from one version to another of the same knowledge object. |

| DP4 Emphasizing development and creativity through knowledge transformations and reflection | Learning must involve different forms of knowledge: declarative, procedural, implicit; and different formats: text, pictures, multimedia, case-experience. Reflection should be promoted with the aim of improving learning and individual and group practices. |

| DP5 Promoting cross-fertilization | It is crucial to create connections beyond formal learning contexts and across communities and institutions to promote the development of new ways of interacting as well as new languages and tools. |

| DP6 Providing flexible tools for developing artifacts and practices | Learning activities and goals should be underpinned by a conscious use of technologies, led by the teacher who deliberately and flexibly selects technologies that allow students to create and share, reflect, and transform knowledge practices and artifacts. |

| Iteration | Participants | Data Collection |

|---|---|---|

| a. y. 2015 | 55 (M: 16–29%, F: 39–71%) | CKP-q (N = 48–87.27%) FG (N = 24 participants. Participants were split across three focus groups.) |

| a. y. 2016 | 54 (M: 26–48%, F: 28–52%) | CKP-q (N = 45–83.33%) FG (N = 32 participants. Participants were split across four focus groups) |

| Design Principle | Implementation in the Course | Blended Setting |

|---|---|---|

| DP1 Organize activities around shared objects | The meaningful and shared object around which the course is organized is students’ documentation of a pedagogical scenario meant to be implemented at school or at university. Intermediate collaborative objects are:

| Artifacts’ building–online Artifacts’ sharing-in presence |

| DP2 Supporting integration of personal and collective agency and work | Students are divided into groups of 9 to 11 members and participate in discussion by bringing their own ideas about the topic to be discussed by the group. Through the first module discussion, key shared understandings are distilled and captured in a collaboratively built cognitive map. In the second module, students’ personal and shared understandings are ‘tested’ through the common activity of analyzing collected writings. Interaction and interdependence are supported by the role-taking strategy. Four stable roles are assigned, in turn, to students in each module: social tutor, synthetizer, skeptic, and responsible for the collaborative artifact. In addition, during classroom collaborative activities, one student carries the role of critical observer. | Group discussions-online Collected writings’ analysis-in-presence Role Taking-online and in-presence |

| DP3 Fostering long-term processes of knowledge advancement | The course is structured into three consecutive modules of approximately 4 weeks. Each module addresses a different part of the curriculum, and it is based on iterative activities of knowledge production and object creation. Knowledge advancement is reinforced through peer-review sessions during which each group is asked to look at the objects of two other groups and to provide constructive feedback. Later, each group works on improving their products, based on the feedback provided. | Peer-review sessions-in-presence Artifacts’ revising-online |

| DP4 Emphasizing development and creativity through knowledge transformations and reflection | Different forms of knowledge and practices are involved in the course: from spontaneous discussions to the representation of concepts through conceptual maps; from reading and commenting on academic articles to knowledge building discussions; and from theoretical lessons to designing and reviewing concrete projects. Moreover, individual and collective reflection on the learning process is generated through:

| Knowledge building discussions, academic articles–online Theoretical lessons, evaluation discussions–in presence Conceptual maps, project works, observer critical report–online and in presence |

| DP5 Promoting cross-fertilization | Real “school world” enters the learning contexts, leading students to experience genuine school practices. The creation of the pedagogical scenario is supported by a guiding template, which highlights the crucial aspects to keep in mind when planning a learning course (e.g., learning goals, evaluation, tools, etc.). | Learning course planning–online and in presence |

| DP6 Providing flexible tools for developing artifacts and practices | The course is based on blended collaborative knowledge-building activities, hosted in the Moodle platform (http://elearning.uniroma1.it, accessed on 23 September 2021). Each group has its own dedicated Moodle course to discuss, add external resources, upload documents, share collaborative products, and much more. Each course is linked to tools such as Padlet (for brainstorming activities), Google drawings (to create online conceptual maps), and Google documents (for the collaborative writing of the pedagogical scenario). | Digital tools–online and in presence |

| Item | First Iteration |

|---|---|

| To ask questions relating to the practices of another field. | 3.35 |

| To present my expertise to representatives of another field. | 3.02 |

| To collaborate with representatives of other fields. | 2.98 |

| Improvement Area | Feedback |

|---|---|

| Course structure | Difficulty to connect Modules 2 (collecting/analyzing children’s spontaneous writing) and 3 (developing a pedagogical scenario about collaborative use of technologies), also because of compressed timing |

| Learning strategies | For some roles, the contribution to the group work is not clear (e.g., for the critical observer) |

| Collaboration | Unequal levels of contribution and participation in the group |

| Design Principle | Changes Introduced in Response to CKP-q | Changes Introduced in Response of FG | Blended Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| DP1 | |||

| DP2 | 1. Individual agency strengthened through an additional task introduced in module 2, preliminary to the collective discussion: the individual research and mapping of learning experiences using technology. | Online | |

| DP3 | 1. Revised times and contents of module 2 to reinforce the advancement of knowledge: The analysis of children’s spontaneous writing is replaced by the study of experiences of use of technologies in teaching, which becomes the basis for module 3. | In–presence and online | |

| DP4 | 1. Critical-observer role modified: The observation grid focuses now on the whole module and not just on single classroom activities; it is completed online, thus becoming more easily usable by the group. | Online | |

| DP5 | (CKP scales 5–6) Introduction of teachers and school principals in the activities of Module 3, as external experts offering feedback to improve the pedagogical scenario, before its revision | Online | |

| DP6 |

| Item | Year 2015 | Year 2016 |

|---|---|---|

| To ask questions relating to the practices of another field. | 3.35 | 3.53 |

| To present my expertise to representatives of another field. | 3.02 | 3.24 |

| To collaborate with representatives of other fields. | 2.98 | 3.24 |

| Improvement Area | Feedback |

|---|---|

| Learning strategies | Not being able/confident in commenting on other groups’ products Poor discussions mainly shaped as long monologue |

| Collaboration | Unequal level of contribution and participation in the group |

| Design Principle | Changes Introduced in Response to CKP-q | Changes Introduced in Responses of FG | Blended Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| DP1 | |||

| DP2 | 1 Added two new roles: researcher, scenario reviser 2. Self-Monitoring questionnaire (SM-q) introduced to promote a structured and ongoing reflection about one’s own participation in and contribution to the group work 3. Provided specific assignments on how to constructively discuss, that is, by using explicit quotations and references to peer contributions in the Moodle Web forums | Online and in presence Online Online and in presence | |

| DP3 | 1. Peer review session reinforced with two new assignments: (1) the groups build the criteria they then use to give feedback; (2) the groups clearly state how to improve their own product after seeing that of their colleagues | ||

| DP4 | 1. Introduced teacher’s formative evaluation of the maps through a classroom session, showing the changes between the first and second versions and the impact of given and received feedback | In presence | |

| DP5 | (CKP scales 5–6) Experts coming to class lessons to listen to group presentations. Students experiencing assessment practices. | In presence | |

| DP6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sansone, N.; Cesareni, D.; Bortolotti, I.; McLay, K.F. The Designing and Re-Designing of a Blended University Course Based on the Trialogical Learning Approach. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11100591

Sansone N, Cesareni D, Bortolotti I, McLay KF. The Designing and Re-Designing of a Blended University Course Based on the Trialogical Learning Approach. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(10):591. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11100591

Chicago/Turabian StyleSansone, Nadia, Donatella Cesareni, Ilaria Bortolotti, and Katherine Frances McLay. 2021. "The Designing and Re-Designing of a Blended University Course Based on the Trialogical Learning Approach" Education Sciences 11, no. 10: 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11100591

APA StyleSansone, N., Cesareni, D., Bortolotti, I., & McLay, K. F. (2021). The Designing and Re-Designing of a Blended University Course Based on the Trialogical Learning Approach. Education Sciences, 11(10), 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11100591