Older People’s Media Repertoires, Digital Competences and Media Literacies: A Case Study from Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How do the respondents report combining the use of traditional media and the internet? What kind of media repertoires emerge?

- What kinds of digital competences and media literacies emerge from respondents’ accounts? Are ethical and aesthetic issues quoted, or just critical ones?

- What kinds of support and training do they get and wish to receive?

2. Older People’s Media Use and Media Repertoires

3. Older People’s Digital Competences and Media Literacies

4. Methodological Framework

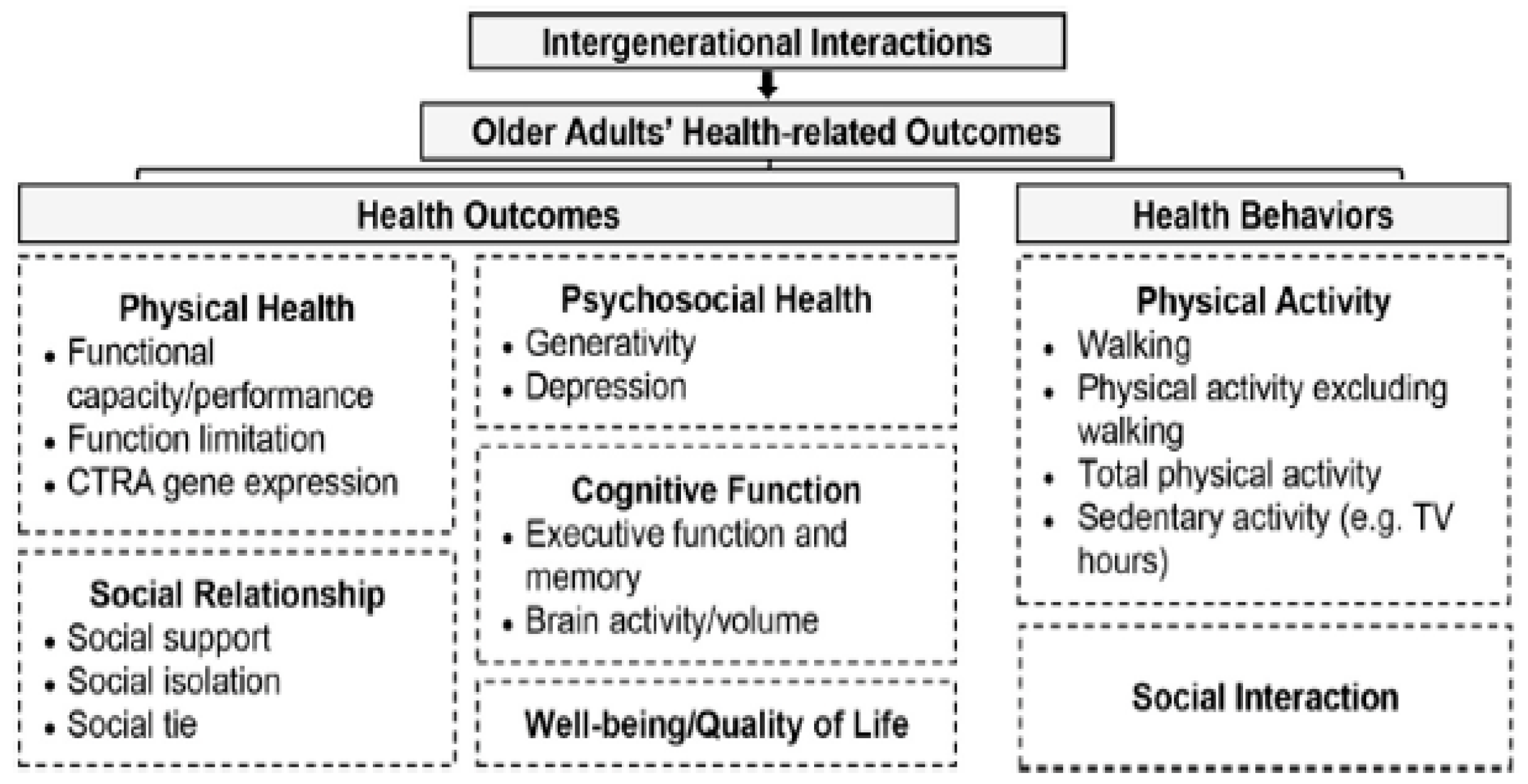

- Sharing part of everyday and personal life [37];

- Responding to ongoing problems and barriers [38];

- Introducing approaches where all individuals have the capacity to contribute and benefit [39];

- Fostering positive perceptions of each other [41];

- Encouraging communication through sharing stories and memories [36]; and

- Increasing desired participation and enjoyment and experiencing generativity [42].

5. Results

5.1. Media Repertoires: Four Emerging Profiles

“I am interested in ‘wearable’ media, as they say, like smartwatches, Bluetooth headphones, but the cost is still a bit high.”(65 years old, male)

“My mobile phone has become indispensable for me since I am alone: even when I travel by car, it gives me security, whether or not I have a possible health emergency.”(77 years old, female)

“I have a profile on Twitter, but I use it very little; Facebook, at least three or four times a week, then sometimes I am more connected, I use social channels if I want to contact friends, and I stay in contact with former colleagues. I use social media in these forms, I don’t use them for nonsense; I don’t have Instagram, a lot of time it’s a waste of time. Then Messenger [on Facebook] and YouTube, sometimes when there is something interesting.”(66 years old, female)

“Mainly Facebook, but I also have Instagram for photos and YouTube to see something, but I don’t produce or rarely.”(73 years old, male)

“Let’s say, you have Facebook [always available]: you’re on the bus, you don’t know what to do and you go to Facebook and play a little bit rather than answer to someone, but it’s a use… I don’t use Facebook to do anything other than have social contact.”(66 years old, female)

“If they give me the phone instead, I will stay there for hours. Because I like to chat a lot, loneliness gives me sadness, even if my husband is in the house, but we are always [only] the two of us.”(75 years old, female)

“I like to listen so much to the radio, which is my favourite medium, the first [technological] thing I had in my youth. It was the first instrument we had in the family. Dad bought it. I was not even fifteen-sixteen years old and for me it was an immense joy because there was nothing in the village where we lived. So we were one of the first families to have this mobile radio. It was beautiful: there were transmissions, there was the record player and I put the records and I spent the day like this, especially in the morning when I was doing crafts at home.”(75 years old, female)

“It depends on what I have to do and see: if it is a show I did not see last night, I open the computer; if it is less challenging, I take the phone; and if I want to play some games, I do it with the computer or with the smartphone if I do not have the computer. I turn on the TV to have company as I live alone in my house.”(65 years old, female)

“In the morning, as soon as I wake up, I send my friends a good morning with my phone through WhatsApp. Then maybe I have other jobs to do because I’m not in the house all day. When I am at home, I turn on the TV, so I hear talking and I feel a bit of background noise. TV provides me with some company. (…) The thing I definitely use the most is the TV because I turn it on and let it talk all day, more to hear someone talking.”(65 years old, female)

“I also make payments on the phone. The phone is easier and faster because I have it to hand and even if I’m out I can do everything.”(67 years old, female)

“Today, I used the computer to check my emails and order some useful products for the family from Amazon, [and I used] the smartphone to check the bank account and the tablet to read the news of the local newspapers.”(68 years old, male)

“I started with the PC when there was no Windows, eh… because of my job, I had to take all possible and imaginable courses and, in particular, get a PC… immediately.”(77 years old, female)

“[I use the internet] mainly to process my hobbies, create, research, information, communicate, read the various newspapers and integrate paper stuff.”(77 years old, female)

5.2. Digital Competences and Media Literacies

“I mean the ability to understand what can be the consequences of the use of that specific medium or that application (good or bad use); critical competence is also the ability to dominate that medium and not to be dominated, right?! Or to acquire information and critically analyse it in terms of truthfulness.”(69 years old, male)

“There is a problem, which, however, comes much further, as it also occurred with old media: the ability to read a newspaper or an article and try to understand the right meaning, what can be true or not. I mean, the internet is a very powerful tool and therefore also a tool of disinformation and therefore [it is necessary] to have knowledge and critical knowledge.”(73 years old, male)

“The media have burdened the situation: especially about vaccines, they have said ‘yes’ and ‘no’; people are already stressed, not understanding the situation they are experiencing, so they do not understand if they should do one thing or the other.”(65 years old, female)

“Critical competence for me is when your PC crashes and you don’t have the basic notions to work on it and you always have to ask for external help.”(77 years old, female)

“I have a lot of distrust and I am very protective of my privacy. I don’t like conflict situations, so I never wanted to get close to these tools, which may have some positive aspects, but with respect to which I have a great distrust.”(77 years old, female)

5.3. Support and Training

“Young people and children must be helped to avoid them accessing websites that can be described as particularly harmful, such as pornographic sites or other platforms that they should not open on their own.”(68 years old, male)

“No, I think everyone [old and young people]. Because even a child, well, maybe a little one, just plays games, but the older ones must know that they cannot post just anything on social media because it can have serious consequences. And also posting images of people, you can’t do it without asking them… I mean photos, for privacy issues.”(67 years old, female)

“It has changed, yes, because I have used them more, as there was no physical contact and you had to get in touch through your smartphone.”(82 years old, female)

“I often attend the Teatro No’hma in the Lambrate area and now I’m watching their programmes on YouTube. I mean, they were important in pandemic times.”(66 years old, female)

“Yes, you definitely use them more because you have more time. I never had time before. Now, with the pandemic, you are at home and use them more.”(67 years old, female)

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- Introducing and discussing complex themes—the interviewers were able to make digital issues accessible to older people by providing experiences taken from their life, using a common language (and some dialect expressions), enabling storytelling, and making the interviewee comfortable with conversational adjustments (rephrasing and clarifying);

- Increasing competence in students as warm-media experts—in the interviews, by discussing with peers and with teachers, they started a metacognitive process on their on their attitude as researcher;

- Creating a more accessible and user-centred digital service [1] in designing meaningful media educative activities. The students followed different approaches with older people; thus, when dealing with people aged 65+, media education should start and be strictly linked to people’s competence. As such, media educators should start from an instrumental/functional approach and move to a critical and ethical dimension. However, with people over 80 years old, media educators should propose methods close to early childhood approaches (playfulness, storytelling, and memoires).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rasi, P. On the Margins of Digitalization. The Social Construction of Older People and the Internet. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland, 2021. Available online: https://erepo.uef.fi/handle/123456789/25307 (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Carenzio, A.; Ferrari, S.; Rivoltella, P.C. Media diet today: A framework and tool to question media uses. In Media Education at the Top; Ruokamo, H., Kangas, M., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2021; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, R. The state of media literacy: A response to Potter. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 2011, 55, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasi, P.; Vuojärvi, H.; Ruokamo, H. Media education for all ages. J. Media Lit. Educ. 2019, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivoltella, P.C. Nuovi Alfabeti; Editrice Morcelliana: Brescia, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rasi, P. Internet nonusers. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of the Internet; Warf, B., Ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 532–539. [Google Scholar]

- Matikainen, J. Medioiden media—Internet. In Suomen Mediamaisema; Nordenstreng, K., Nieminen, H., Eds.; Vastapaino: Tampere, Finland, 2017; pp. 323–341. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, M.A.; Kahn, R. Internet. Computer network. In Encyclopedia Britannica; 2020; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/technology/Internet (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Istat. Citizens and ICT. 2019. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2019/12/Cittadini-e-ICT-2019.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Bakardjieva, M. Internet Society: The Internet in Everyday Life; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, B.; Kim, J.; Baumgartner, L.M. Informal learning of older adults in using mobile devices: A review of the literature. Adult Educ. Q. 2019, 69, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, T.; Viscovi, D. Warm experts for elderly users: Who are they and what they do? Hum. Technol. 2018, 14, 324–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasi, P.; Lindberg, J.; Airola, E. Older service users’ experiences of learning to use eHealth applications in sparsely populated health care settings in Northern Sweden and Finland. Educ. Gerontol. 2021, 47, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänninen, R.; Taipale, S.; Luostari, R. Exploring heterogeneous ICT use among older adults—The warm experts’ perspective. New Media Soc. 2020, 23, 1584–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisdorf, B.; Petrovčič, A.; Grošelj, A. Going online on behalf of someone else: Characteristics of Internet users who act as proxy users. New Media Soc. 2020, 23, 2409–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). Use of Internet Services by Citizens. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-singlemarket/en/use-internet-and-online-activities (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Nimrod, G. Older audiences in the digital media environment. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarenmaa, K. Päivittäisestä Mediakattauksesta Löytyy Jokaiselle Jotain Digikuilun Molemmin Puolin. Tieto & Trendit Website, 14 February 2020. Statistics Finland. 2020. Available online: https://www.stat.fi/tietotrendit/artikkelit/2020/paivittaisesta-mediakattauksesta-loytyy-jokaiselle-jotain-digikuilun-molemmin-puolin/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Giskov, C.; Deuze, M. Researching new media and social diversity in later life. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N. Media, Society, World: Social Theory and Digital Media Practice; Polity Press: Malden, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Telecommunication Union. Measuring Digital Development. Facts and Figures. 2020. Available online: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/FactsFigures2020.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Auditel-Censis, S.R. Tra Anziani Digitali e Stranieri Iperconnessi, l’Italia in Marcia Verso la Smart TV; Redattore Sociale: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ofcom. Adults’ Media Use and Attitudes: Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/196375/adults-media-use-and-attitudes-2020-report.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Carretero, S.; Vuorikari, R.; Punie, Y. DigComp 2.1. The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens with Eight Proficiency Levels and Examples of Use; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; Available online: https://bit.ly/3rsJV6B (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Punie, Y. Preface. DIGCOMP: A Framework for Developing and Understanding Digital Competence in Europe; Ferrari, A., Ed.; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium; Joint Research Centre–Institute for Prospective Technological Studies: Seville, Spain, 2013; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptaszek, G. Media literacy outcomes, measurement. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Literacy; Hobbs, R., Mihailidis, P., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 1067–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Euroopan Unionin Neuvosto. Neuvoston Suositus Elinikäisen Oppimisen Avaintaidoista. Euroopan Unionin Virallinen Lehti, C 189/01. 2018. Available online: https://bit.ly/3focv72 (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Lubarsky, N. Rememberers and remembrances: Fostering connections with intergenerational interviewing. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 1997, 28, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubrium, J.F.; Holstein, J.A. Narrative practice and the coherence of personal stories. Sociol. Q. 1998, 39, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. Narrative identity. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein, J.A.; Gubrium, J.F. The Active Interview; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A.; Frey, J.H. The Interview. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: London, UK, 2005; Volume 3, pp. 695–727. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction; Sage: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants Part 2: Do they really think differently? Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M. Intergenerational programs in schools: Considerations of form and function. Int. Rev. Educ. 2002, 48, 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spudich, D.; Spudich, C. Welcoming intergenerational communication and senior citizen volunteers in schools. Improv. Sch. 2010, 13, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westcott, L. Baby day: An intergenerational program. Perspectives 1987, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holmes, C.L. An intergenerational program with benefits. Early Child. Educ. J. 2009, 37, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrott, S.E.; Bruno, K. Shared site intergenerational programs: A case study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2007, 26, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, C.J.; Lee, M.M. Montessori-Based activities as a transgenerational interface for persons with dementia and preschool children. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2011, 9, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galbraith, B.; Larkin, H.; Moorhouse, A.; Oomen, T. Intergenerational programs for persons with dementia: A scoping review. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2015, 58, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, G.; Bolender, B. Research: Age to age. Resident outcomes from a kindergarten classroom in the nursing home. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2010, 8, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Lee, C.; Foster, M.; Bian, J. Intergenerational communities: A systematic literature review of intergenerational interactions and older adults’ health-related outcomes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 264, 113374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakardjieva, M.; Smith, R. The internet in everyday life: Computer networking from the standpoint of the domestic user. New Media Soc. 2001, 3, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, C.L. Learning How to Ask: A Sociolinguistic Appraisal of the Role of the Interview in Social Science Research (No. 1); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, M.; Larson, C.E.; Greenwood, H. Intergenerational shared sites in Hawaii. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2011, 9, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrott, S.E.; Smith, C.L. The complement of research and theory in practice: Contact theory at work in nonfamilial intergenerational programs. Gerontologist 2011, 51, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi, E.E.; Zenga, M. Senior, Nuove Tecnologie, Competenze Finanziarie e COVID-19; Università degli Studi Milano-Bicocca: Milano, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rasi, P.; Vuojärvi, H.; Rivinen, S. Promoting media literacy among older people: A systematic review. Adult Educ. Q. 2021, 71, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Finland. Use of Information and Communications Technology by Individuals. 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/31t5Tff (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Dannefer, D.; Settersten, R.A., Jr. The study of the life course: Implications for social gerontology. In The Sage Handbook of Social Gerontology; Dannefer, D., Phillipson, C., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen, M.M.; Gergen, K.J. Positive aging. In Ways of Aging; Gubrium, J.F., Holstein, J.A., Eds.; Blackwell: Hobocken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, N. Resilience and spirituality: Foundations of strengths perspective counseling with the elderly. Educ. Gerontol. 2004, 30, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Competence Areas | Competencies |

|---|---|

| Information and data literacy | Browsing, searching, and filtering data, information, and digital content Evaluating data, information, and digital content Managing data, information, and digital content |

| Communication and collaboration | Interacting through digital technologies Sharing through digital technologies Engaging in citizenship through digital technologies Collaborating through digital technologies Netiquette Managing digital identity |

| Digital content creation | Developing digital content Integrating and re-elaborating digital content Copyright and licences Programming |

| Safety | Protecting devices Protecting personal data and privacy Protecting health and well-being Protecting the environment |

| Problem solving | Solving technical problems Identifying needs and technological responses Creatively using digital technologies Identifying digital competence gaps |

| Dimensions of New Media Literacy | Focus |

|---|---|

| Critical | Analysis, understanding |

| Aesthetical | Form, creativity |

| Ethical | Responsibility, resistance |

| ID | Gender (Q1) 1 = F, 2 = M | Age (Q2) | Place of Residence (Q3) 1 = Town, 2 = Small City, 3 = Big City | Living Condition (Q4) 1 = at Home with Relatives, 2 = at Home alone, 3 = in Hospice | Relationship with Interviewer (Q5) 1 = Father/Mother, 2 = Grandfather/ Grandmother, 3 = Uncle/Aunt, 4 = Neighbour, 5 = Great-Grandfather/Mother, 5 = Family Friend, 6 = Cousin, n.a. = Not Answered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 69 | Piedmont, 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 2 | 65 | Piedmont, 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 2 | 65 | Lombardy, 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 | 98 | Piedmont, 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 5 | 1 | 75 | Piedmont, 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 6 | 1 | 77 | Lombardy, 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 7 | 1 | 73 | Lombardy, 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 8 | 1 | 74 | Emilia-Romagna, 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | 1 | 73 | Lombardy, 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 10 | 1 | 65 | Piedmont, 1 | 2 | n.a. |

| 11 | 1 | 66 | Lombardy, 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 12 | 2 | 73 | Trentino Alto Adige, 2 | 1 | 4 |

| 13 | 1 | 81 | Lombardy, 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 14 | 1 | 65 | Friuli, 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 15 | 1 | 77 | Lombardy, 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 16 | 1 | 66 | Emilia-Romagna, 1 | 2 | 6 |

| 17 | 1 | 73 | Lombardy, 3 | 2 | 3 |

| 18 | 1 | 82 | Lombardy, 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 19 | 1 | 67 | Lombardy, 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 20 | 1 | 77 | Valle D’Aosta, 2 | 2 | 5 |

| 21 | 1 | 65 | Lombardy, 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 22 | 1 | 75 | Liguria, 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 23 | 1 | 68 | Lombardy, 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 24 | 2 | 68 | Sardegna, 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Profile | N | Age | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analogic | 6 | 73+ (5), 65 (1) | F (6) |

| Accidental user | 6 | 65−68 (3), 73+ (3) | F (5), M (1) |

| Digital-instrumental | 7 | 65−68 (3), 73+ (3) | F (6), M (1) |

| Hybridised | 5 | 65−68 (3), 73+ (2) | M (3), F (2) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carenzio, A.; Ferrari, S.; Rasi, P. Older People’s Media Repertoires, Digital Competences and Media Literacies: A Case Study from Italy. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11100584

Carenzio A, Ferrari S, Rasi P. Older People’s Media Repertoires, Digital Competences and Media Literacies: A Case Study from Italy. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(10):584. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11100584

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarenzio, Alessandra, Simona Ferrari, and Päivi Rasi. 2021. "Older People’s Media Repertoires, Digital Competences and Media Literacies: A Case Study from Italy" Education Sciences 11, no. 10: 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11100584

APA StyleCarenzio, A., Ferrari, S., & Rasi, P. (2021). Older People’s Media Repertoires, Digital Competences and Media Literacies: A Case Study from Italy. Education Sciences, 11(10), 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11100584