Abstract

Digital media are part of everyday life and have an intergenerational appeal, entering older people’s agendas, practices, and habits. Many people aged over 60 years lack adequate digital competences and media literacies to support learning, well-being, and participation in society, thus imposing a need to discuss older people’s willingness, opportunities, and abilities to use digital media. This study explored older people’s media use and repertoires, digital competences, and media literacies to promote media literacy education across all ages. The article discusses the data from 24 interviews with older people aged 65 to 98 years in Italy to answer the following research questions: What kinds of media repertoires emerge? What kinds of competences and media literacies can be described? What kinds of support and training do older people get and wish to receive? The analysis of the data produced four specific profiles concerning media repertoires: analogic, accidental, digital-instrumental, and hybridised users. Media literacy is still a critical framework, but the interviewees were open to opportunities to improve their competences. The use of digital media has received a strong boost due to the pandemic, as digital media have been the only way to get in touch with others and carry out their daily routine.

1. Introduction

Digital media are part of everyday life and have an intergenerational appeal, entering older people’s agenda, practices, and habits. Societies today are in a rapid process of digitalisation, affecting public administration, private commercial services, educational services, and healthcare and welfare services. However, many people over 60 years of age lack adequate digital competences and media literacies to support their learning, well-being, everyday life, and participation in today’s digitalised society [1]. Therefore, there is a need to examine older people’s willingness, opportunities, and abilities to use digital media in their everyday life. Older people’s digital competences need to be supported to enable them to live in today’s digitalised media environment with responsibility and consciousness, to prevent problematic issues, and to promote a healthy media diet [2]. However, as well as making older service users responsible in the process of digital service delivery, there is also a need to create more accessible and user-centred digital services for older people [1].

To promote media literacy education across all ages and beyond school contexts [3,4,5], this study explores older people’s media use and repertoires, digital competences, and media literacies. The study seeks to answer the following research questions:

- How do the respondents report combining the use of traditional media and the internet? What kind of media repertoires emerge?

- What kinds of digital competences and media literacies emerge from respondents’ accounts? Are ethical and aesthetic issues quoted, or just critical ones?

- What kinds of support and training do they get and wish to receive?

2. Older People’s Media Use and Media Repertoires

A large proportion of older people are internet nonusers, may never have used the internet, or have used the internet before but stopped for various reasons [6]. The internet is understood herein as the medium of media [7] and network of networks [8], which hosts a large and rapidly growing number of diverse media for activities such as social networking, information retrieval, and the provision of public and private services.

In the context of the present research, in Italy, the situation concerning older people’s digital media use was summarised by Istat [9]: Within families with people aged 65+ (living alone), the presence of a high-speed internet connection stops at 34% (the average in Italy is 75%). Of the Italian population, 42% of people aged 65–74 years use the internet, which drops to 12% for people aged 75+. Age also influences the choice of device used for accessing the internet: 19% use a personal computer (5% being the average in Italy). Some differences related to gender have become particularly marked between older people. Of women aged 60+ years, 40% use smartphones exclusively to access the internet, which is 14% more than their male peers. Men aged 65+ are instead characterised by the exclusive use of a personal computer (22% compared to 14% of women). Women show an advantage in the use of communication services, which is particularly marked for women aged 65+ who use messaging services (9% more than men).

Older people often experience technical challenges in using the internet; therefore, social support networks play an important role in their internet use [10,11,12,13]. The line between internet use and non-use is sometimes hard to define because even if older people are nonusers, they may let or make others do things for them online (so-called proxy use, see, e.g., [14,15]). On average, in Europe and beyond, older people’s range of online activities is narrower than that of younger age groups [16]. For example, older people use social networking services less than younger age groups [17]. Based on a large cross-European audience research project, Nimrod described older people’s media use as media use traditionalism, meaning that most seniors prefer and adhere to traditional mass media, such as print newspapers and magazines, radio, and TV (see also [18]). However, previous research on older people’s media use points to diversity in terms of the expectations, motivation, attitudes, practices, meanings, experiences, and consequences related to older people’s internet use [1].

Older people often have extensive experience with traditional media, which they continue to actively follow [17,18]. To cite Giskov and Deuze [19] (pp. 405–406), people “do” their media: “People grow up and mature with particular media, move through life phases with media, and form affective relationships with and through their media.” Therefore, as Nimrod [17] argued, research on older people’s media repertoires—that is, research on how older people combine the use of traditional media and the internet—is needed (see also [1]). Looking at older people’s media repertoires contributes to a more positive view of older people in terms of their media use, digital competences, and media literacies, which helps to identify and draw attention to older people’s capabilities and positive attributes, rather than the deficits and problems in using digital media.

Older people’s existing abilities and media preferences will, in the present study, be considered using a positive and comprehensive approach from the perspective of media repertoires, enquiring how older people combine their online and offline media practices into meaningful repertoires [17,19]. For Giskov and Deuze [19] (p. 406), studying media repertoires means “looking at the various ways people ‘do’ their media, rather than documenting distinct media usage in generic categories such as time spent, equipment used, and skills deployed.” Giskov and Deuze [19] (p. 406) further argued that people use media as ensembles and that media should be studied both in their material and emotional contexts “in terms of what they are and what they mean.” This focus also entails theorising media as a practice (see [20]); that is, looking at what people do with or in relation to media and what they say about media.

3. Older People’s Digital Competences and Media Literacies

There is significant variation in older people’s digital competences, that is, in their abilities to access, use, and produce digital media content [14,17,21]. Many older people use digital media through assisted use, co-use, or proxy use [12,14,15]. In the context of the present study, research [22] indicates that 57% of older Italian people (65+) have low competences, 23% have fundamental skills, and 10% claim to have a high level of competence. For women aged 80+, the use of the internet is almost non-existent and is very limited for men of the same age. According to research, 79% of people over 65 have at least one mobile phone or smartphone to communicate with the world. Overall, previous research has described older people’s digital competences as partly inadequate, albeit diverse, when it comes to fully functioning in the digital society [1]. For example, research indicates that some older people’s skills are inadequate for protecting their safety and data privacy [23].

According to DigComp, the Digital Competence Framework for Citizens, which is provided by the European Commission [24,25], digital competence refers to “the confident, critical and creative use of ICT to achieve goals related to work, employability, learning, leisure, inclusion, and/or participation in society” [25] (p. 2). The latest version of the framework, DigComp 2.1 [24], defines the following five competence areas: information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, and safety and problem solving (Table 1). It is noteworthy that according to the framework, digital competence is a highly multi-dimensional competence and contains knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

Table 1.

DigComp 2.1 competence areas and competencies [24].

Digital competence strongly overlaps with the concept of media literacy, which has typically been defined as the ability to access and use, understand and evaluate, and create media content and communications in a variety of contexts, including digital contexts [26]. After the release of DigComp 2.1, the Council of the European Union included media literacy as one of the digital competences in its recommendations for the key competences of lifelong learning [27]. However, differences exist between the concepts of digital competence and media literacy, one key difference being that digital competence has been assessed as being narrower and more instrumental in its focus, whereas media literacy is understood to represent a more critical approach to digital media [1].

According to Rivoltella [5], we can describe at least the following three “dimensions” of new literacies (Table 2), which refer to new media literacies that are necessitated by the new digital media system: the critical, aesthetic, and ethical dimensions. The critical dimension “pertains to the access and understanding of cultural forms and represents the continuity between New Literacy and Media Literacy traditionally seen” [5] (p. 195). The aesthetic dimension is linked to the concept of “beauty” and the aesthetic form of media products and artefacts: “Beauty lives a story of repression and lack of consideration throughout the history of media applications. It is a consequence of the focus on content, on the cognitive and structural dimension with respect to the history of the West” [5] (p. 196). The ethical dimension refers to two main elements: responsibility and resistance, both of which are linked to media activism and digital citizenship. “The issue of responsibility is brought into play by the authorial nature of digital and social media and by the transformations linked to the access to public space in the information society” [5] (p. 196).

Table 2.

Dimensions of new media literacies.

4. Methodological Framework

The research is framed within the qualitative research methodology: Data were acquired through a method that we conceptualised as a “warm intergenerational interview” (cf. [28]). We recruited students enrolled in the master’s degree programme in Media Education at Catholic University of the Sacred Heart to conduct interviews with older people. From a media literacy education perspective [3,4,5], we understand the interview as a pedagogical action that is based on intergenerational interaction and aims to promote both the interviewees’ and the interviewers’ media literacies. As Gubrium and Holstein [29] noted at the end of the 1990s, the research interview has become a means of contemporary storytelling, where people divulge life accounts in response to interview inquiries. The life storytelling approach [30] is fundamental, above all, for older people to express and make sense of the digital world. Interview participants are “actively” constructing knowledge around questions and responses [31], to cite Fontana and Frey [32] (p. 647): “Each interview context is one of interaction and relation; the result is as much a product of this social dynamic as it is a product of accurate accounts and replies.” Questions are never neutral and are a powerful means of calling on members’ cultural repertoires of ways of speaking. “By analysing how people talk to one another, one is directly gaining access to a cultural universe and its content of moral assumptions” [33] (p. 108).

Looking at the digital world, we consider that a “digital native” [34] who could even be close to the interviewee can act as an interviewer to set up intergenerational interaction. We understand intergenerational activity as a “social vehicle that creates purposeful and ongoing exchanges of resources and learning among older and younger generations” [35] (p. 306) and enhances the interviewer’s speaking and listening skills [36]. Previous research has pointed to several benefits that result from this kind of interaction. Among these, we highlight the following, which are most closely connected to media literacy education:

- Sharing part of everyday and personal life [37];

- Responding to ongoing problems and barriers [38];

- Introducing approaches where all individuals have the capacity to contribute and benefit [39];

- Providing and promoting the inclusion of older people to participate [40,41];

- Fostering positive perceptions of each other [41];

- Encouraging communication through sharing stories and memories [36]; and

- Increasing desired participation and enjoyment and experiencing generativity [42].

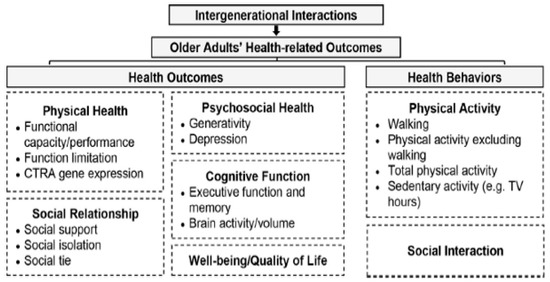

In addition, as shown by Zhong et al.’s [43] systematic review, intergenerational activities spurred by this interview could have positive impacts on older people; they are positively associated with older people’s physical health, psychosocial health, cognitive function, social relationships, and well-being/quality of life (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Health benefits of intergenerational interactions [43].

Our concept of a “warm intergenerational interview” was inspired by Bakardjieva’s [10,44] notion of “warm experts,” who mediate between the technology, the situation, and the needs of novice users. Warm experts are close friends, relatives, or other personal acquaintances who can assist in the process of learning and appropriation of digital technologies. Warm experts are particularly relevant with older people, who tend to prioritise strong ties in finding support they need. Inspired by the concept, we use the concept “warm intergenerational interview” to refer to a research interview where a young person native to the digital world acts as the interviewer but simultaneously practices “warmness” through carefully attending to what the interviewee is saying and how s/he is saying it. The interviewer should practice the specific sociolinguistic frame of interviews and the participants’ communicative norms and interpretive frameworks to determine the meaning of the interview talk [45]. The interviewer can also help the interviewee navigate in and understand the digital world and, in this way, resembles a warm expert, as defined by Bakardjieva [10].

The aim of a warm intergenerational interview is to develop a secure and respectful relationship between the interviewer and the interviewed, who should develop their interactions organically without structured guidance in a nurturing, safe, and calm environment [46]. From a media literacy education perspective, secure, respectful, and reciprocal relationships are the first principles of learning: A positive contact transfers cultural understanding and develops the ability to communicate across cultures [38]. In a warm intergenerational interview, the relationship between interviewers and interviewees is used as a bridge to make the last mentioned most comfortable and the first mentioned more attentive. The interviews can also be viewed as occasions to get closer and reinforce the bonds between people. As teachers, we believe that engaging our learners in direct experience and focused reflection is a meaningful way to increase knowledge, develop skills, clarify values, and develop students’ capacities to contribute to their communities.

In practice, for the data collection process, we engaged the students enrolled in the course module “Supporting older people’s digital competences and media literacies” (2 ECTS, responsible instructor: the third author), which was part of the larger course titled “Information Literacy and Web Languages” (12 ECTS, responsible instructor: the second author). Among these, 23 people decided to participate voluntarily as interviewers. From the ethical perspective, the 24 voluntary interviewees were reached by the standard research protocol adopted by our university, which is the “information notice for the processing of personal data.” The students asked the respondents for their informed consent and explained that the respondents’ identity would not be revealed in any of the research reports and that the interviewee was free to withdraw from the research at any time.

The four-week module was delivered through hybrid seminars, online video lectures, and students’ independent study in May 2021. The aim of the module was to help students gain a deeper understanding of older people, their digital competences and media literacies, and the media literacy education that is best suited to the older population. For their assignment, the students interviewed Italian people aged 65+. The interviews targeted older people’s media use and preferences, digital competences, media literacies, and how these were acquired. The data collection process proceeded through the following four steps:

1. Formative session. The authors presented and discussed the interview protocol with the students and pointed out the conditions required to set up a warm intergenerational interview. The protocol included instructions regarding the age of the interviewees (65+), the mode (face to face/online) of the interview, the maximum length of the interview (appr. 60 min), the interviewee’s informed consent, and how to audio record the interview. The students were also provided with a list of questions and materials to cover and deliver during the interview. However, we encouraged students to be flexible during the interview in terms of its structure and content (e.g., [47]). We encouraged the students to use their personal concerns and knowledge and to respond carefully to what the interviewees were saying. Prior to the interviews, students were offered hybrid seminars, video lessons, and readings on the topics of the course module.

2. Interviews. The students selected one person (65+) from their family or social environment (neighbours, family, friends) with whom to conduct and record an interview. The students delivered the audio recording of the interview to the authors. The interview protocol included questions grouped under the following six topics: (1) background information (age, gender, place of residence, housing situation, type of relation with the interviewer), (2) conceptions of digital media, (3) use of media, (4) digital media appropriation (i.e., learning to use digital media), (5) media literacy, and (6) the meaning of the COVID-19 pandemic in the use of media. Examples of interview questions include the following: How have you learned to use digital media such as the internet? Have you come across the concept of “media literacy”? In your opinion, what is media literacy? Where do you think it is most needed nowadays? Would you like to learn some media literacy skills?

3. Sharing and discussing the interviews. At the end of the module, the students shared and discussed their interviews with their peers and the three authors in a hybrid two-hour seminar. The aim of this activity was to foster a media literacy education perspective.

4. Reflection. Finally, we administered a questionnaire to foster in students the reflective practitioner perspective [48] and to develop a meta-reflective process. “Students who participate in the intergenerational interview process have the opportunity to discover and identify the roots of their own values and to examine and reflect on the values of an individual more experienced at living. At the same time the process is illuminating for the older person who is given the opportunity to talk to someone who was just beginning this lifelong discovery process” [28] (p. 145).

The first two authors analysed the respondents’ media repertoires by coding the types of media they used, the time spent on each medium, and the motivations for use (leisure, work, relationship, information). Second, the data were coded in terms of the aspects of digital competences and media literacy presented earlier in this manuscript. The interview questions were co-produced by the authors.

5. Results

The interviewees were 24 older people (5 men and 19 women) aged 65 to 98 years old (average age = 75) from Italy. Apart from one person living in a big city, the interviewees lived in small cities or villages close to main municipalities (Milan, Brescia, Aosta, and Trento). All participants were from the north of the country from west to east, and 12 lived alone, nine lived with their spouse, two lived with a daughter, and another lived with her sister and brother-in-law. The sample under study is presented in the following table (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sample of the study.

5.1. Media Repertoires: Four Emerging Profiles

In the analyses of the data, media repertoires were coded with the following criteria: types of media owned by the interviewee, time spent with the media, apps, and media preferences.

The interviewee’s media repertoires were not computer-driven: five of the 24 people owned and used a computer, three of whom were 65; eight had a personal computer, five of whom were under 70. In our case study, lower age was connected to the use of computers and PCs. Furthermore, the uses were connected to previous jobs and they were deeply linked to the professional life of each interviewee. This group of interviewees had an interest in technical lexicons related to innovative technologies, as one interviewee explained:

“I am interested in ‘wearable’ media, as they say, like smartwatches, Bluetooth headphones, but the cost is still a bit high.”(65 years old, male)

The interviewees appeared to be a “smartphone generation”: 20 of the 24 had a smartphone (two more people had a mobile phone, but likely with no internet connection, so not properly a smartphone), and two answers were missing. Of the 24 interviewees, 13 had a tablet computer. However, three did not use it at all. Three interviewees had an e-book reader, one mentioned Alexa (77 years old, female), and one had a smartwatch (67 years old, female). The interviewees reported that smartphones are easy to use and important for personal safety:

“My mobile phone has become indispensable for me since I am alone: even when I travel by car, it gives me security, whether or not I have a possible health emergency.”(77 years old, female)

Social media formed a moderate part of the interviewees’ media repertoires (Twitter: 1 user; Instagram: 2 users; TikTok: 1 user). One interviewee (73 years old, male) reported using a mix of social media applications: TikTok, YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook. Seven interviewees reported using YouTube, not as prosumers (persons who both consume and produce) but as users, accessing content online and sometimes on the television set: “In the evening, in particular, if there is nothing interesting on television I try to watch something on YouTube” (65 years old, male). The other three people who mentioned YouTube used it in combination with other social media:

“I have a profile on Twitter, but I use it very little; Facebook, at least three or four times a week, then sometimes I am more connected, I use social channels if I want to contact friends, and I stay in contact with former colleagues. I use social media in these forms, I don’t use them for nonsense; I don’t have Instagram, a lot of time it’s a waste of time. Then Messenger [on Facebook] and YouTube, sometimes when there is something interesting.”(66 years old, female)

“Mainly Facebook, but I also have Instagram for photos and YouTube to see something, but I don’t produce or rarely.”(73 years old, male)

Only four interviewees reported using games on their devices (one decided to quit), as they mostly preferred puzzler magazines. The interviewees talked about social media as a sort of diversion, a means to spend time and to get in contact with friends. Six of them had a Facebook profile, as one reported:

“Let’s say, you have Facebook [always available]: you’re on the bus, you don’t know what to do and you go to Facebook and play a little bit rather than answer to someone, but it’s a use… I don’t use Facebook to do anything other than have social contact.”(66 years old, female)

As for other social media applications, 14 interviewees quoted WhatsApp as their favourite app and eight defined video call/chat apps as a new entry to their repertoires since the start of the pandemic. Four interviewees mentioned banking apps and two used Google to obtain news and information. Residual apps included Duolingo, Booking, apps connected to transportation, and forecast and supermarket apps (due to the pandemic for online shopping). This shift led us to a specific form of use: interest-driven, practical, and goal-oriented.

Concerning their favourite device, smartphones appeared to be valuable resources because they are portable and offer a combination of different functions in one tool. Smartphones appeared as the most favourite device for 11 interviewees, eight of whom chose the smartphone and one other device, such as a tablet computer (3), television set (3), or computer (2):

“If they give me the phone instead, I will stay there for hours. Because I like to chat a lot, loneliness gives me sadness, even if my husband is in the house, but we are always [only] the two of us.”(75 years old, female)

In terms of traditional media, 13 interviewees reported reading magazines, 17 read newspapers and books, 23 watched television, and 9 preferred the radio (4 used to listen to radio programmes, but they moved to television in recent years). Radio is still a “media of their memory”:

“I like to listen so much to the radio, which is my favourite medium, the first [technological] thing I had in my youth. It was the first instrument we had in the family. Dad bought it. I was not even fifteen-sixteen years old and for me it was an immense joy because there was nothing in the village where we lived. So we were one of the first families to have this mobile radio. It was beautiful: there were transmissions, there was the record player and I put the records and I spent the day like this, especially in the morning when I was doing crafts at home.”(75 years old, female)

Somehow, television and digital media represented an easy match and the combination was not coincidental:

“It depends on what I have to do and see: if it is a show I did not see last night, I open the computer; if it is less challenging, I take the phone; and if I want to play some games, I do it with the computer or with the smartphone if I do not have the computer. I turn on the TV to have company as I live alone in my house.”(65 years old, female)

Television was the absolute favourite device for four interviewees, whereas radio was the favourite device and media for only one person. This finding is quite interesting because many of them declared themselves to be radio lovers.

The analysis of the data produced four specific profiles concerning media repertoires: the analogic user, the accidental user, the digital-instrumental user, and the hybridised user. The analogic profile is based on a definite analogic media repertoire dominated by newspapers, television, and radio with no expansion to the digital world. The accidental user profile came to use digital devices just by chance, for example, when there is nothing interesting on TV and they have no specific interest or skills. The digital-instrumental profile includes a relatively broad use of digital technologies and the internet, especially to meet specific practical needs linked to bank issues or payments and the use is very goal-oriented (traveling, shopping etc.). Finally, the hybridised profile manifests clearly hybridised media repertoires with an assortative integration of digital and traditional media in daily practices. This is interesting because it reveals a specific focus: someone who chooses media devices and services and consciously moves from one to the other and knows how they work.

Our sample was quite balanced if we consider the mix of media uses and the meaning of the media themselves (material and emotional contexts). The hybridised profile was representative of a minority (5), followed by the accidental user profile and the analogic profile (6 each), followed by the digital-instrumental (7), especially if we consider the massive use of smartphones and the internet via mobile devices. Age was a variable, but not so clearly: It was evident in the analogic profile, quite important in the hybridised profile, and very balanced in the other profiles (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of profiles.

Six people were strictly analogic (no smartphone, just an old mobile phone and just for talking; no internet; and no other digital media, with a declared analogic practice and somehow a very distant idea of technologies and the internet). They were all female and aged over 73 years (except for one), and commented on their repertoires, for example, in the following way: “I really never thought to use them (other digital media), also because I don’t need them” (65 years old, female). The accidental user profile was represented by six people, and the following excerpt sheds light on their perspectives:

“In the morning, as soon as I wake up, I send my friends a good morning with my phone through WhatsApp. Then maybe I have other jobs to do because I’m not in the house all day. When I am at home, I turn on the TV, so I hear talking and I feel a bit of background noise. TV provides me with some company. (…) The thing I definitely use the most is the TV because I turn it on and let it talk all day, more to hear someone talking.”(65 years old, female)

A digital-instrumental profile was manifested in seven people’s accounts, as the following excerpts demonstrate:

“I also make payments on the phone. The phone is easier and faster because I have it to hand and even if I’m out I can do everything.”(67 years old, female)

“Today, I used the computer to check my emails and order some useful products for the family from Amazon, [and I used] the smartphone to check the bank account and the tablet to read the news of the local newspapers.”(68 years old, male)

Five people corresponded to the hybridised profile. One respondent had an extensive past with computers for work reasons:

“I started with the PC when there was no Windows, eh… because of my job, I had to take all possible and imaginable courses and, in particular, get a PC… immediately.”(77 years old, female)

The following is another example of a hybridised profile:

“[I use the internet] mainly to process my hobbies, create, research, information, communicate, read the various newspapers and integrate paper stuff.”(77 years old, female)

5.2. Digital Competences and Media Literacies

Ten respondents claimed to understand the concept of media literacy (or at least were able to cite a definition). They were mainly women, whose age had no impact on this aspect: four corresponded to the hybridised profile, two to the accidental users, one to the analogic profile, and three were digital-instrumental users. The respondents reported interesting ideas about media literacies, particularly about their ability to critically analyse media contents:

“I mean the ability to understand what can be the consequences of the use of that specific medium or that application (good or bad use); critical competence is also the ability to dominate that medium and not to be dominated, right?! Or to acquire information and critically analyse it in terms of truthfulness.”(69 years old, male)

“There is a problem, which, however, comes much further, as it also occurred with old media: the ability to read a newspaper or an article and try to understand the right meaning, what can be true or not. I mean, the internet is a very powerful tool and therefore also a tool of disinformation and therefore [it is necessary] to have knowledge and critical knowledge.”(73 years old, male)

One respondent expressed her concern about the difficulties in trying to analyse the overflow of information and determining which information concerning the COVID-19 pandemic was trustworthy:

“The media have burdened the situation: especially about vaccines, they have said ‘yes’ and ‘no’; people are already stressed, not understanding the situation they are experiencing, so they do not understand if they should do one thing or the other.”(65 years old, female)

Notably, some respondents confused digital competence with having a digital “alphabet”:

“Critical competence for me is when your PC crashes and you don’t have the basic notions to work on it and you always have to ask for external help.”(77 years old, female)

Therefore, the main terms were the ability to understand the consequences of media use, to analyse information, and to reflect on a wide range of nuances within the media architecture (with a specific focus on privacy). The pandemic made information literacy a huge topic even in the mainstream media: If we consider the Italian scenario, we assisted in the diffusion of fake news, misinformation, and incorrect information on COVID-19, vaccines, and many other issues related to the situation worldwide.

Most interviewees saw social media as somewhat problematic due to privacy and security issues, which can be interpreted as distrust of digital communication systems and as insecurity about their digital competences in protecting their safety (e.g., protecting devices, personal data, and privacy) (see [24]). The following interview excerpt demonstrates these concerns:

“I have a lot of distrust and I am very protective of my privacy. I don’t like conflict situations, so I never wanted to get close to these tools, which may have some positive aspects, but with respect to which I have a great distrust.”(77 years old, female)

5.3. Support and Training

We asked the respondents whether they wanted to improve their competences concerning digital media and media literacy. The interviewers, when needed (in 15 cases), explained the meaning of digital competence and media literacy to make the interviewees more aware and to give them a framework through which to answer the question. The majority (11 people) were open to new courses and opportunities to improve or build their competences, nine people were not interested, and three were unsure (one did not respond). This result supports that collected by a recent study of older people, COVID-19, and technologies [49] in which many of the Italian respondents stated that they did not need to learn more about the use of new technologies (12%), a fact worth reflecting on to avoid taking “learning need” for granted.

The reasons for the unwillingness to learn new media literacies ranged from “laziness” to a self-perception of being unable to learn, which reflected an age-related representation of old people and digital media as living in two very different worlds. Some respondents reported that they could resort to proxy use; in other words, asking other people to perform digital tasks for them (see also [12,14,15]: “I don’t find it necessary at my age” (81, female, analogic); “not anymore, you know?! My mind is too tired” (75, female); “I am not against the use of digital tools, but out of laziness and the fact that I have a favourable situation that allows me to solve problems having others solve them, I do not intend to develop [further competences]” (69, male).

Among those who knew little about media literacy and digital competence, seven people claimed to be interested in developing their competences (all female, four were 73+ years old, three were accidental users, and two were in the analogic profile). Some of them wanted to be “more autonomous,” without having to depend on others to run procedures and manage practical actions such as organising data and using digital tools for images and photographs. Trying to imagine the structure of media literacy training (cf. [50]), one respondent suggested having a peer-to-peer situation (with people of the same age) and other training performed by young people (as they know more about digital issues). The interviewees suggested that the course should not be online.

Are digital competences and media literacies a matter for young or older people? The findings show that the respondents had mixed views, but many considered these issues to be transgenerational:

“Young people and children must be helped to avoid them accessing websites that can be described as particularly harmful, such as pornographic sites or other platforms that they should not open on their own.”(68 years old, male)

“No, I think everyone [old and young people]. Because even a child, well, maybe a little one, just plays games, but the older ones must know that they cannot post just anything on social media because it can have serious consequences. And also posting images of people, you can’t do it without asking them… I mean photos, for privacy issues.”(67 years old, female)

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic had a strong positive impact on almost all the respondents’ digital media uses and practices. This impact has also been found in other European countries [51]. Many of those who previously considered digital media something unfamiliar or unimportant started to access it more frequently and made digital media part of their daily routine in terms of practical procedures and emotional investment. Some respondents discovered new digital applications (e.g., Classroom, Google platforms, and Jamboard) and invested more time in video conferencing and WhatsApp to see their relatives and reinforce family bonding, as this interview excerpt demonstrates:

“It has changed, yes, because I have used them more, as there was no physical contact and you had to get in touch through your smartphone.”(82 years old, female)

In particular, during the COVID-19 pandemic, YouTube was experienced by some respondents as a “remedial” element. Many Italian institutions streamed live or made content accessible online:

“I often attend the Teatro No’hma in the Lambrate area and now I’m watching their programmes on YouTube. I mean, they were important in pandemic times.”(66 years old, female)

Connected media helped them connect to the world. There was another node, as well—many people, especially the ones already working, discovered that they had a lot of time:

“Yes, you definitely use them more because you have more time. I never had time before. Now, with the pandemic, you are at home and use them more.”(67 years old, female)

6. Discussion

This study examined older Italian people’s media use and repertoires, digital competences, and media literacies. The study sought to answer the following research questions: How do the respondents report combining the use of traditional media and the internet? What kinds of media repertoires emerge? What kinds of digital competences and media literacies emerge from respondents’ accounts? Are ethical and aesthetic issues quoted, or just critical ones? What kinds of support and training do they get and wish to receive?

The interviewees reported that traditional media (television, newspapers, radio, magazines) were significant in their everyday lives, thus corroborating Nimrod’s [17,18] findings about older European people’s media-use traditionalism. The findings corroborate previous research (e.g., [16,17]) in that social media formed only a moderate part of the interviewees’ media repertoires. Most of the interviewees reported that they experienced social media as somewhat problematic and had concerns about privacy and safety issues, thus pointing to possible insecurities about their digital competences to protect their safety (see [24]).

The results include four specific profiles concerning older people’s media repertoires: the analogic, accidental user, digital-instrumental, and hybridised profiles. These profiles corroborate previous research by making visible the diversity of older people’s digital media use [1,9]. However, the digital-instrumental and hybridised profiles in particular support looking at older people’s media use from a positive viewpoint, as these profiles show how older people successfully use a relatively broad array of digital technologies and the internet for purposes meaningful to them. In particular, the hybridised profile shows how older people successfully integrate digital and traditional media into their daily practices. These results are worth capitalising on, since very often researchers have addressed older people’s digital competences and media literacies from the viewpoint of deficits and barriers of use. Here, the positive outlook is inspired by how, for example, social gerontology and educational gerontology have accentuated diversity and heterogeneity as well as positive aspects and strengths related to ageing and old age [52,53,54].

7. Conclusions

In terms of the respondents’ digital competences and media literacies as well as their willingness to develop these skills, there was variation between the respondents. This is in line with previous research [1,14,17,21]. Furthermore, our study corroborates studies indicating that older people often need social support and resort to proxy use of digital technologies and media [12,14,15]. Notably, social support and proxy use are not always welcomed by older people, as some of the respondents of the present study reported an interest in developing their digital competences to be “more autonomous” and not having to “depend on others.” In terms of media technologies, most of the respondents had and used a smartphone. Notably, smartphones appeared to be the favourite device of many interviewees.

At the methodological level, this research tested the “warm expert intergenerational interview,” which was useful for the following:

- Introducing and discussing complex themes—the interviewers were able to make digital issues accessible to older people by providing experiences taken from their life, using a common language (and some dialect expressions), enabling storytelling, and making the interviewee comfortable with conversational adjustments (rephrasing and clarifying);

- Increasing competence in students as warm-media experts—in the interviews, by discussing with peers and with teachers, they started a metacognitive process on their on their attitude as researcher;

- Creating a more accessible and user-centred digital service [1] in designing meaningful media educative activities. The students followed different approaches with older people; thus, when dealing with people aged 65+, media education should start and be strictly linked to people’s competence. As such, media educators should start from an instrumental/functional approach and move to a critical and ethical dimension. However, with people over 80 years old, media educators should propose methods close to early childhood approaches (playfulness, storytelling, and memoires).

This study has some limitations. For a more comprehensive and representative knowledge of older Italian people’s media repertoires, digital competences, and media literacies, data from a larger number of respondents, as well as complementary data collection methods such as participant observation, log data, and performance tests, are needed. The findings of the present study show that some older people do not fully understand what is meant by digital competence and media literacy and that some are unwilling to develop their competences due to, for example, a negative perception of themselves as old-age incompetent learners. However, the study also showed that some older people would be willing to learn new digital competences and media literacies, for example, through peer mentoring. The practical implication of the results is, therefore, that adequate information, as well as training and support related to older people’s media literacies, should be provided. Finally, information and support that address older people’s negative conceptions of themselves as learners should be provided.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R., A.C., S.F.; methodology, S.F. and P.R.; formal analysis, A.C. and S.F.; data curation, A.C.; writing—original draft preparation P.R., S.F., and A.C.; writing—review and editing, P.R. and A.C. A.C. wrote Section 5.2 and Section 5.3; A.C. and P.R. wrote Section 2 and Section 3; S.F. and P.R. wrote Section 4, Section 6 and Section 7; A.C. and S.F. wrote Section 5.1; The other authors wrote Section 1. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the nature of the data retrieved and to the specific context of the study, that is a university course.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. All participants have been fully informed about anonymity, aims of the interview and data use.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Data are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rasi, P. On the Margins of Digitalization. The Social Construction of Older People and the Internet. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland, 2021. Available online: https://erepo.uef.fi/handle/123456789/25307 (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Carenzio, A.; Ferrari, S.; Rivoltella, P.C. Media diet today: A framework and tool to question media uses. In Media Education at the Top; Ruokamo, H., Kangas, M., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2021; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, R. The state of media literacy: A response to Potter. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 2011, 55, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasi, P.; Vuojärvi, H.; Ruokamo, H. Media education for all ages. J. Media Lit. Educ. 2019, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivoltella, P.C. Nuovi Alfabeti; Editrice Morcelliana: Brescia, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rasi, P. Internet nonusers. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of the Internet; Warf, B., Ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 532–539. [Google Scholar]

- Matikainen, J. Medioiden media—Internet. In Suomen Mediamaisema; Nordenstreng, K., Nieminen, H., Eds.; Vastapaino: Tampere, Finland, 2017; pp. 323–341. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, M.A.; Kahn, R. Internet. Computer network. In Encyclopedia Britannica; 2020; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/technology/Internet (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Istat. Citizens and ICT. 2019. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2019/12/Cittadini-e-ICT-2019.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Bakardjieva, M. Internet Society: The Internet in Everyday Life; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, B.; Kim, J.; Baumgartner, L.M. Informal learning of older adults in using mobile devices: A review of the literature. Adult Educ. Q. 2019, 69, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, T.; Viscovi, D. Warm experts for elderly users: Who are they and what they do? Hum. Technol. 2018, 14, 324–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasi, P.; Lindberg, J.; Airola, E. Older service users’ experiences of learning to use eHealth applications in sparsely populated health care settings in Northern Sweden and Finland. Educ. Gerontol. 2021, 47, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänninen, R.; Taipale, S.; Luostari, R. Exploring heterogeneous ICT use among older adults—The warm experts’ perspective. New Media Soc. 2020, 23, 1584–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisdorf, B.; Petrovčič, A.; Grošelj, A. Going online on behalf of someone else: Characteristics of Internet users who act as proxy users. New Media Soc. 2020, 23, 2409–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). Use of Internet Services by Citizens. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-singlemarket/en/use-internet-and-online-activities (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Nimrod, G. Older audiences in the digital media environment. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarenmaa, K. Päivittäisestä Mediakattauksesta Löytyy Jokaiselle Jotain Digikuilun Molemmin Puolin. Tieto & Trendit Website, 14 February 2020. Statistics Finland. 2020. Available online: https://www.stat.fi/tietotrendit/artikkelit/2020/paivittaisesta-mediakattauksesta-loytyy-jokaiselle-jotain-digikuilun-molemmin-puolin/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Giskov, C.; Deuze, M. Researching new media and social diversity in later life. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N. Media, Society, World: Social Theory and Digital Media Practice; Polity Press: Malden, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Telecommunication Union. Measuring Digital Development. Facts and Figures. 2020. Available online: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/FactsFigures2020.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Auditel-Censis, S.R. Tra Anziani Digitali e Stranieri Iperconnessi, l’Italia in Marcia Verso la Smart TV; Redattore Sociale: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ofcom. Adults’ Media Use and Attitudes: Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/196375/adults-media-use-and-attitudes-2020-report.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Carretero, S.; Vuorikari, R.; Punie, Y. DigComp 2.1. The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens with Eight Proficiency Levels and Examples of Use; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; Available online: https://bit.ly/3rsJV6B (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Punie, Y. Preface. DIGCOMP: A Framework for Developing and Understanding Digital Competence in Europe; Ferrari, A., Ed.; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium; Joint Research Centre–Institute for Prospective Technological Studies: Seville, Spain, 2013; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptaszek, G. Media literacy outcomes, measurement. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Literacy; Hobbs, R., Mihailidis, P., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 1067–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Euroopan Unionin Neuvosto. Neuvoston Suositus Elinikäisen Oppimisen Avaintaidoista. Euroopan Unionin Virallinen Lehti, C 189/01. 2018. Available online: https://bit.ly/3focv72 (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Lubarsky, N. Rememberers and remembrances: Fostering connections with intergenerational interviewing. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 1997, 28, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubrium, J.F.; Holstein, J.A. Narrative practice and the coherence of personal stories. Sociol. Q. 1998, 39, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. Narrative identity. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein, J.A.; Gubrium, J.F. The Active Interview; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A.; Frey, J.H. The Interview. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: London, UK, 2005; Volume 3, pp. 695–727. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction; Sage: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants Part 2: Do they really think differently? Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M. Intergenerational programs in schools: Considerations of form and function. Int. Rev. Educ. 2002, 48, 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spudich, D.; Spudich, C. Welcoming intergenerational communication and senior citizen volunteers in schools. Improv. Sch. 2010, 13, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westcott, L. Baby day: An intergenerational program. Perspectives 1987, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holmes, C.L. An intergenerational program with benefits. Early Child. Educ. J. 2009, 37, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrott, S.E.; Bruno, K. Shared site intergenerational programs: A case study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2007, 26, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, C.J.; Lee, M.M. Montessori-Based activities as a transgenerational interface for persons with dementia and preschool children. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2011, 9, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galbraith, B.; Larkin, H.; Moorhouse, A.; Oomen, T. Intergenerational programs for persons with dementia: A scoping review. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2015, 58, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, G.; Bolender, B. Research: Age to age. Resident outcomes from a kindergarten classroom in the nursing home. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2010, 8, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Lee, C.; Foster, M.; Bian, J. Intergenerational communities: A systematic literature review of intergenerational interactions and older adults’ health-related outcomes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 264, 113374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakardjieva, M.; Smith, R. The internet in everyday life: Computer networking from the standpoint of the domestic user. New Media Soc. 2001, 3, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, C.L. Learning How to Ask: A Sociolinguistic Appraisal of the Role of the Interview in Social Science Research (No. 1); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, M.; Larson, C.E.; Greenwood, H. Intergenerational shared sites in Hawaii. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2011, 9, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrott, S.E.; Smith, C.L. The complement of research and theory in practice: Contact theory at work in nonfamilial intergenerational programs. Gerontologist 2011, 51, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi, E.E.; Zenga, M. Senior, Nuove Tecnologie, Competenze Finanziarie e COVID-19; Università degli Studi Milano-Bicocca: Milano, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rasi, P.; Vuojärvi, H.; Rivinen, S. Promoting media literacy among older people: A systematic review. Adult Educ. Q. 2021, 71, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Finland. Use of Information and Communications Technology by Individuals. 2020. Available online: https://bit.ly/31t5Tff (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Dannefer, D.; Settersten, R.A., Jr. The study of the life course: Implications for social gerontology. In The Sage Handbook of Social Gerontology; Dannefer, D., Phillipson, C., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen, M.M.; Gergen, K.J. Positive aging. In Ways of Aging; Gubrium, J.F., Holstein, J.A., Eds.; Blackwell: Hobocken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, N. Resilience and spirituality: Foundations of strengths perspective counseling with the elderly. Educ. Gerontol. 2004, 30, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).