Diagnosing Causes of Pre-Service Literature Teachers’ Misconceptions on the Narrator and Focalizer Using a Two-Tier Test

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the origins of pre-service literature teachers’ misconceptions regarding the narrator and focalizer?

- What misconceptions regarding the narrator and focalizer arise from each cause?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Meaning of Misconception and Research Necessity

2.2. Origins of Diverse Misconceptions

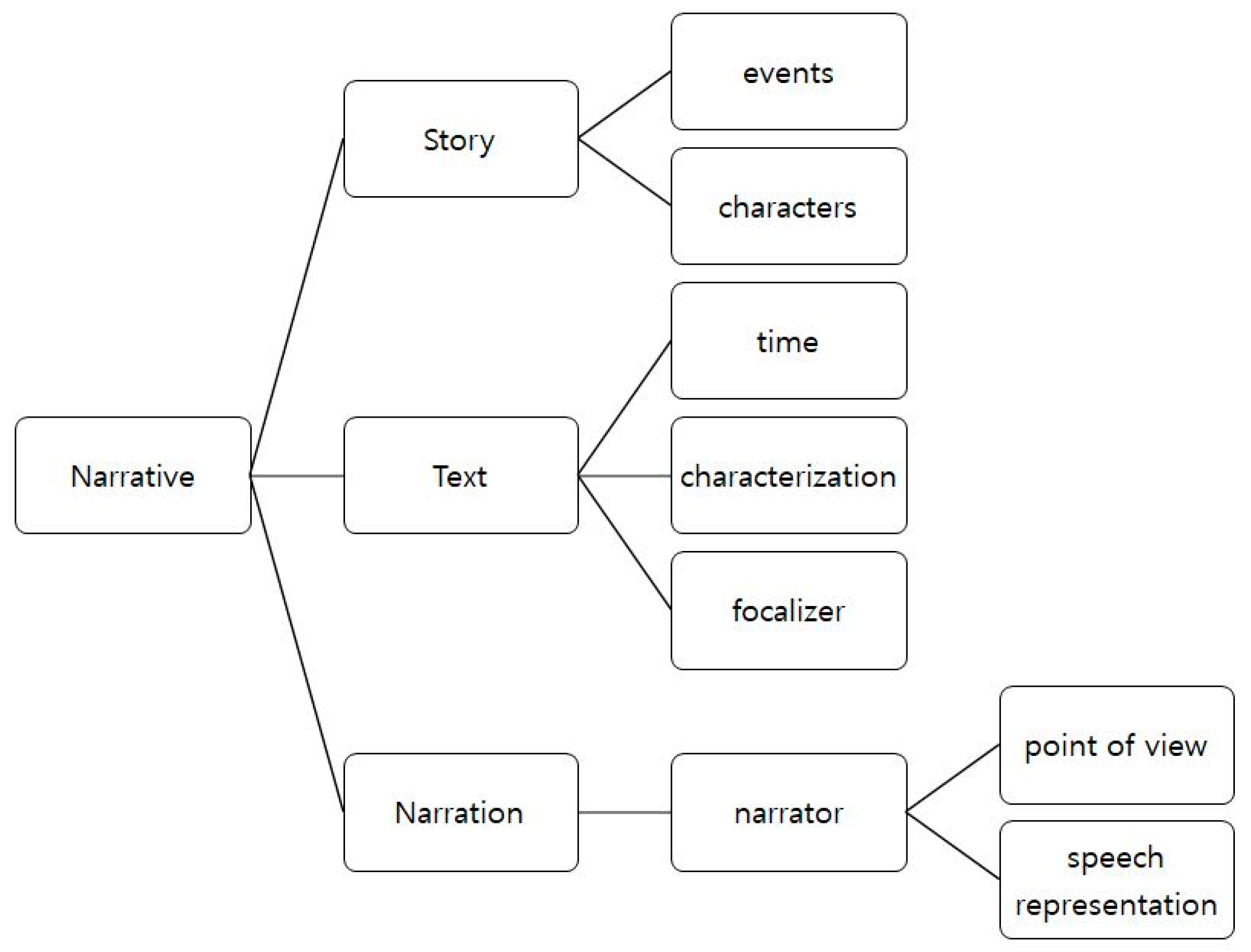

2.3. Meaning and Educational Context of the Narrator and Focalizer

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Research Instrument

3.3. Research Process and Analysis Method

4. Results

4.1. Prevalence of Misconceptions by Cause

4.2. Analysis of the Origins of Diverse Misconceptions

4.2.1. Over-Contextualization of Everyday Experiences

4.2.2. Misunderstanding of Terms

4.2.3. Transfer of Misconceptions from Textbooks

4.2.4. Miscategorization Due to Prior Knowledge

5. Discussion

5.1. Overcoming Literary Misconceptions in the Curriculum and Textbooks

5.2. Class Design for Overcoming Literary Misconceptions

5.3. Literary Misconceptions as the Content of Teacher Education

5.4. Limitations of the Present Study

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire Used in the Study Reported in This Paper (in Korean)

| (9국05-04) 작품에서 ⓐ보는 이나 ⓑ말하는 이의 관점에 주목하여 작품을 수용한다. |

| 상판을 쳐들고 대어 설 숫기도 없었으나, 계집 편에서 정을 보낸 적도 없었고, 쓸쓸하고 뒤틀린 반생이었다. 충줏집을 생각만 하여도 철없이 얼굴이 붉어지고 발밑이 떨리고 그 자리에 소스라쳐 버린다. 충줏집 문을 들어서서 술좌석에서 짜장 동이를 만났을 때에는 어찌된 서슬엔지 발끈 화가 나 버렸다. 상 위에 붉은 얼굴을 쳐들고 제법 계집과 농탕치는 것을 보고서야 견딜 수 없었던 것이다. 녀석이 제법 난질꾼인데 꼴사납다. 머리에 피도 안 마른 녀석이 낮부터 술 처먹고 계집과 농탕이야. 장돌뱅이 망신만 시키고 돌아다니누나. 그 꼴에 우리들과 한몫 보자는 셈이지. 동이 앞에 막아서면서부터 책망이었다. 걱정두 팔자요 하는 듯이 빤히 쳐다보는 상기된 눈망울에 부딪힐 때, 결김에 따귀를 하나 갈겨 주지 않고는 배길 수 없었다. 동이도 화를 쓰고 팩하고 일어서기는 하였으나, 허 생원은 조금도 동색하는 법 없이 마음먹은 대로는 다 지껄였다. |

| “결혼하면 남자는 영원히 자기 곁을 떠나지 않으리라는 그 한 가지 이유만으로 자기 아내를 소중히 할 줄을 몰라”하고 불행해했다. 여자는 갑자기 그 생각이 났다. 이제 나를 소유했다고 여기기 때문에 저이는 나를 소중히 하지 않는 거야. 그러길래 내 주름살 따위가 눈에 띄기 시작한 거라구. 여자는 남자의 피곤한 얼굴에 대고 까다로운 표정으로 맞선다. “차 뭘로 할래?” 이 카페의 젊은 주인 남자가 옆에 다가와 서자 남자가 묻는다. “내가 좋아하는 게 뭔지 아직도 몰라?” “커피 마시지?” “무슨 커핀데? 나한테 관심 있다면 그 정도는 알아야지.” 남자는 여자의 난데없는 응석도 마땅찮거니와 무엇보다 주인 남자를 옆에 세워 놓고 자기들끼리의 감정을 노출하는 일 따위는 경박하다고 생각하여 얼굴을 찡그린다. 여자가 재촉한다. “응? 말해 봐. 내가 무슨 커피 좋아하는지.” “피곤하게 그러지 마. 애들도 아니고, 어울리지 않게.” 여자의 표정이 대번 일그러지는 것을 보면서 남자는 그냥 커피와 녹차를 주문한다. ‘그렇게까지 말할 작정은 아니었는데.’ 담배에 불을 붙이며 남자는 오늘 같은 날은 차라리 만나지 말걸 그랬다는 후회도 얼핏 들었지만 그보다는 오늘따라 유난히 까다롭게 구는 여자를 이해할 수가 없다는 쪽으로 생각이 기운다. |

Appendix B. Questionnaire Used in the Study Reported in This Paper (in English)

| (9kor05-04) the learner should receive literary works with a focus on the perspective of ⓐ the viewer or ⓑ speaker in the literary work. |

| Women played a very minor role in his personal life. Extremely self-conscious of his pitted complexion, Heo Saengwon lacked the courage to lift his face to approach them. Likewise, no woman had ever sought after him with affection. His years had been distorted and lonely. At the mere thought of the Chungju-Inn, his face blushed like that of a little boy, and his legs become weak and wobbly as if he would collapse. The moment Heo Saengwon passed through the gate of Chungju-Inn, his tired eyes locked onto Dong-i. He could not help a surging rage. Propped at a wine table, he consumed more than his fill, but all the while, he womanized as though he were a man of experience. He lashed out immediately, startling Dong-i with a stern scolding. How unsightly it is to see a fellow still damp behind the ears drinking himself stupid while he goes around whoring in broad daylight! You go around disgracing the good name of all respectable peddlers. However, you expect to join us and have a share in our trade! Dong-i’s eyes were simmering with resentment as they scrutinized the older man’s face and shot him a look that seemed to say, “You must have been destined from birth to worry about everything.” With that, Heo Saengwon’s rage boiled over, and he could no longer resist the impulse to slap the boy in the face. Dong-i sprang from his seat in indignation, but that did nothing to deter Heo Saengwon, who refused to be quieted until he had said everything that was on his mind. |

| “A man does not know how to cherish his wife for the one reason that once he marries, she will never leave his side,” she said unhappily. The woman suddenly had that thought. Now that he thinks that he owns me, he does not cherish me. Because of that, my wrinkles began to stand out. The woman turned to the man’s tired face with a worried look. “What would you like?” the man asked as the young male owner of the cafe approached. “You still do not know what I like?” “Coffee, right?” “Which coffee? If you are interested in me, you should know at least that much.” The man grimaced at the woman’s sudden childish act and her revealing their feelings to the male owner standing next to them. The woman urged him. “Well? Tell me. What coffee do I like?” “Stop being so tiring. You are not a child; it does not suit you.” Watching the woman’s face contort, the man simply ordered a coffee and green tea. “I was not planning to go that far.” The man lit a cigarette. Though he instantly regretted meeting that day in the first place, he wondered more why the woman was unusually fussy that day. |

References

- Sullivan, S.C.; Downey, J.A. Shifting educational paradigms: From traditional to competency-based education for diverse learners. Am. Second. Educ. J. 2015, 43, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- DiSessa, A.A. A bird’s-eye view of the “pieces” vs. “coherence” controversy (From the “pieces” side of the fence). In International Handbook of Research on Conceptual Change, 1st ed.; Vosniadou, S., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 35–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pring, R. Closing the Gap: Liberal Education and Vocational Preparation, 1st ed.; Hodder & Stoughton: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, R.J.; Bell, B.F.; Gilbert, J.K. Science teaching and children’s views of the world. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 1983, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M.; Alkis, S. Misconceptions in geography. Geogr. Educ. 2010, 23, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J. A Study on Pre-Service Teachers’ Misconceptions about the Viewer. Korean Lang. Educ. Res. 2018, 53, 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, J. Using bridging analogies and anchoring intuitions to deal with students’ preconceptions in physics. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1993, 30, 1241–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiyatmoko, A.; Shimizu, K. Literature review of factors contributing to students’ misconceptions in light and optical instruments. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2018, 13, 853–863. [Google Scholar]

- DiSessa, A.A. A history of conceptual change research: Threads and fault lines. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, 1st ed.; Sawyer, R.K., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 265–281. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, M.T.H. Three types of conceptual change: Belief revision, mental model transformation, and categorical shift. In International Handbook of Research on Conceptual Change, 1st ed.; Vosniadou, S., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, S.B. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film, 3rd ed.; Cornell University: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 151–152. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, W.C. The Rhetoric of Fiction, 2nd ed.; The University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1983; pp. 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, H.P. The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 233–234. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, G. Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, 3rd ed.; Cornell Univ. Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 286–287. [Google Scholar]

- National Curriculum Information Center (NCIC). Available online: http://ncic.re.kr/mobile.kri.org4.docSavePrint.do?&orgNo=10059943 (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- McMillan, J.H.; Schumacher, S. Research in Education: A Conceptual Introduction, 5th ed.; Addison Wesley Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, G.J.; Strike, K.A.; Hewson, P.W.; Gertzog, W.A. Accommodation of a scientific conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change. Sci. Educ. 1982, 66, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.P.; DiSessa, A.A.; Roschelle, J. Misconceptions reconceived: A Constructivist analysis of knowledge in transition. J. Learn. Sci. 1993, 3, 115–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dole, J.A.; Sinatra, G.M. Reconceptualizing change in the cognitive construction of knowledge. Educ. Psychol. 1998, 33, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmon-Kenan, S. Narrative Fiction: Contemporary Poetics, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 129–130. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, S.B. Coming to Terms: The Rhetoric of Narrative in Fiction and Film, 1st ed.; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel, D.P. The Psychology of Meaningful Verbal Learning: An Introduction to School Learning, 1st ed.; Grune & Stratton: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Beeth, M.E. Teaching for conceptual change: Using status as a metacognitive tool. Sci. Educ. 1998, 82, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, A.T.; Mayer, R.E. Learning by doing versus learning by viewing: Three experimental comparisons of learner-generated versus author-provided graphic organizers. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Content | Subject | Classification Symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1 | A Misconceptions of pre-service teachers and their aspects | 47 participants | A-Serial number |

| Question 2 | B Report difficulties in understanding, learning, and explaining the concepts | B-Serial number | |

| Concept | No Misconception | Has Misconception | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrator | 17 | 30 | 47 |

| Focalizer | 25 | 22 | 47 |

| Origins of Diverse Misconceptions | Code | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Over-contextualization of everyday experiences | O1 | The learner overuses knowledge obtained from everyday experiences in inappropriate contexts to understand concepts. For example, learners may misidentify the narrator and focalizer based on their own experiences with storytelling, or may not perceive their differences. |

| Misunderstanding of terms | O2 | The learner understands the meaning of concepts with an arbitrary understanding of its terms. For example, the learner may understand the term “viewer,” which is used in the curriculum for “focalizer,” as “characters who see something with their eyes.” This is due to the learner’s arbitrary interpretation of the viewer’s “see.” |

| Transfer of misconceptions from textbooks | O3 | The learner understands concepts with the belief that the misconception presented in the textbook is correct. For example, the learner may describe a third-person point of view as the point of view of narrators who speak outside the work. This is because the textbook’s misconception of the third-person point of view was transferred to the learner. |

| Miscategorization due to prior knowledge | O4 | The learner misunderstands the category of the concept to be learned due to their misunderstanding of the relationship between their prior knowledge and the concept to be learned. For example, the learner may equate the distinction between the narrator and focalizer with the distinction between points of view. The distinction between the narrator and focalizer and the distinction between points of view are at different levels. However, the learner establishes their prior knowledge of point of view as the parent category and places the concepts of the narrator and focalizer under it. |

| Concept | Total Number of Misconceptions | Prevalence (Number of Responses) of Misconceptions by Cause | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | O2 | O3 | O4 | ||

| Narrator | 30 | 10%(3) | 33.3%(10) | 66.7%(20) | 43.3%(13) |

| Focalizer | 22 | 13.6%(3) | 40.9%(9) | 0%(0) | 59.1%(13) |

| Code | Example Responses to (Question 2) |

|---|---|

| O1 | [B-10] We usually equate the viewer and the speaker in terms of the character who witnesses an event and speaks about it. For that reason, it was difficult to understand the difference between these two concepts when learning about the viewer and the speaker. It is still difficult to distinguish these two concepts. [B-25] The concept honestly seemed very easy to me if I only heard the words “speaker” and “viewer.” However, even after the explanation of the concepts, it was difficult to understand the difference between them. I could not shake the thought, “Is the person viewing the event, not the same person who will speak about it soon?” [B-27] I see the speaker and viewer as different concepts. When we tell a story, however, it is difficult to understand why the speaker and viewer are divided. |

| Code | Example Responses to (Question 1) |

|---|---|

| O1 | [A-10] The speaker refers to who is narrating from a certain person’s perspective in the text. The speaker in <Text 1> is clear. Heo Saengwon is established as the speaker, and he describes his thoughts about Chungju-zib and Dong-i from his perspective. [A-25] The speaker and viewer refer to who is speaking through a certain person’s eyes. [A-27] The viewer refers to who is conveying the story through a certain person’s eyes. In <Text 2>, a war of nerves between a man and a woman is conveyed through the eyes of someone outside the story. That person is the viewer. |

| Code | Example Responses to (Question 2) |

|---|---|

| O2 | [B-5] “Speak” and “view” in “speaker” and “viewer” are easy terms. The characters in a novel speak with other characters and view events. The character speaking is the speaker, and the character viewing the event is the viewer. However, I am not sure if that is really the case. [B-6] The speaker is related to telling, and the viewer is related to showing. However, I cannot clearly understand how these concepts differ from similar terms such as point of view, person, voice, narrator, and focalizer. [B-29] When I learned the term “speaker,” I thought it was the same as the person telling the story, i.e., the narrator. However, when I learned the term “viewer,” I could not really guess the meaning. “Sees” seems to differ from what characters or the narrator sees, but I am not sure what it means exactly. |

| Code | Example Responses to (Question 1) |

|---|---|

| O2 | [A-5] The characters in a novel speak with other characters and view events. The character speaking is the speaker, and the character viewing the event is the viewer. [A-6] The speaker is a narrative technique in which the narrator directly reveals the characters and events. The viewer is a narrative technique that indirectly reveals the personalities and psychology of the characters and information about the events. [A-29] The narrator is a person who speaks about characters or events through a certain person’s eyes. The narrator is the viewer and the speaker. |

| Code | Example Responses to (Question 2) |

|---|---|

| O3 | [B-3] The speaker of <Text 1> and <Text 2> is a narrator from the omniscient author’s point of view that talks about events, the behavior of characters, and even their psychology from outside the work. However, can the narrator be outside the work? Because the narrator is the writer, he can be outside the work. According to my professor, however, the narrator is an element in the work. I do not understand the textbook’s explanation very well. |

| Code | Example Responses to (Question 1) |

|---|---|

| O3 | [A-33] The speakers of <Text 1> and <Text 2> are both the authors. [A-30] The speaker of <Text 1> talks about characters and events from outside the work as if staring directly at them. [A-3] The speaker of <Text 1> and <Text 2> is a narrator from the omniscient author’s point of view that talks about events, the behavior of characters, and even their psychology from outside the work. |

| Code | Example Responses to (Question 2) |

|---|---|

| O4 | [B-8] I learned about the speaker and viewer as “telling” and “showing” in high school, so it was not difficult to understand these concepts. It was good to have another opportunity to learn them. [B-16] It is difficult to distinguish the speaker and viewer from the point of view. After thinking about it, learning about the point of view in middle school was not this difficult. I was able to understand the first-person point of view and third-person point of view based on person intuitively. [B-42] Viewer and speaker are subordinate concepts of point of view. However, the terms are unfamiliar. I am more familiar with the “first-person central point of view” and “third-person objective point of view.” |

| Code | Example Responses to (Question 1) |

|---|---|

| O4 | [A-8] “Speaker” is a narrative technique in which the narrator directly reveals the personalities and psychology of the characters, information of the events, etc. Because it is a direct narrative technique in which the narrator intervenes between the reader and the characters, the distance between the characters and the reader increases, whereas the distance between the narrator and the reader decreases. [A-8] “Viewer” is a technique that indirectly implies the personalities and psychology of the characters and information of the events through “dialogue” and “actions.” Through dialogue and description, the distance between the characters and reader decreases, while the distance between the narrator and characters and narrator and reader increases. [A-16] The speaker is the omniscient author’s point of view, and the viewer is the first-person central point of view. The viewer of <Text 1> is the first-person central point of view in that the character Heo Saengwon speaks primarily about his own psychology. The speaker of <Text 2> is the omniscient author’s point of view in that the narrator outside the work describes in detail the psychology of two characters. [A-42] The viewer, the person who directly sees the characters or events, can be called the first-person central point of view. The speaker, the person who observes and conveys characters and events, can be called the third-person objective point of view. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jung, J. Diagnosing Causes of Pre-Service Literature Teachers’ Misconceptions on the Narrator and Focalizer Using a Two-Tier Test. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10040104

Jung J. Diagnosing Causes of Pre-Service Literature Teachers’ Misconceptions on the Narrator and Focalizer Using a Two-Tier Test. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(4):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10040104

Chicago/Turabian StyleJung, Jinseok. 2020. "Diagnosing Causes of Pre-Service Literature Teachers’ Misconceptions on the Narrator and Focalizer Using a Two-Tier Test" Education Sciences 10, no. 4: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10040104

APA StyleJung, J. (2020). Diagnosing Causes of Pre-Service Literature Teachers’ Misconceptions on the Narrator and Focalizer Using a Two-Tier Test. Education Sciences, 10(4), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10040104