Abstract

The literature reveals the difficulty of teaching minority languages in multiethnic and multilingual regions. Studies about teachers’ perceptions when instructing a minority language might help stakeholders to design interventions to overcome this problem. The first aim of this study was to describe teachers’ perceptions of type of issues, student complaints, and behaviors when teaching in Basque. The second aim was to state whether there is any relation between the origin of the students, the teachers’ working experience, and working region with the occurrence of issues, type of complaints in class, and the role of students’ parents. The data for this study were collected using an online questionnaire answered by 197 teachers. A descriptive analysis of the answers was performed using SPSS® (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). Chi-square analyses were conducted to study the relation between variables. Results indicate that teachers believe Basque is sometimes undermined in their teaching practice, but no difference is perceived between local and migrant students. Conversely, regarding teachers’ views, negative attitudes toward Basque are mostly influenced by students’ families. This provides evidence to encourage education stakeholders to design better lessons involving the teaching of Basque.

1. Introduction

Teaching minority languages in multiethnic and multilingual environments can pose a challenge to many teachers. Indeed, multilingual environments involving the learning of minority languages are matters of public and private discussion. This sociocultural phenomenon can manifest in more perceptible ways in areas such as the Basque Country, where the use of local languages, the performance of certain ethno-cultural rituals, and language activism are also influenced by an old rooted conflict considered a stakeholder of identity formation [1,2,3].

Bucholtz and Hall [4] point out that scholars often present ethnic and social identities as linked to certain linguistic usages. In this sense, the perception of certain minority languages, and the option to use them instead of hegemonic ones, could be influenced by a specific ethnic affiliation within a particular sociopolitical context [5,6,7]. Hence, it could be said that multilingual societies represent an even more complex panorama regarding the aforementioned scenario.

Similar to other national languages in the world, Basque was largely used in the past to unite, but also to construct needed boundaries for identity formation [8,9,10]. The dualistic discourses arising from the rhetorics of identity [5,6,11] are customary strategies when it comes to identity formation, as the ethnic “us” can only be constructed in opposition to a non-ethnic “otherness” [10,12]. This very same schema remains active in the present through the constitution of alliances and oppositions to minority language [13], often articulated by students to refute their own teachers through the use or non-use of certain languages. The use of a hegemonic language against a minority one could be considered in certain contexts, such as Basque, as an ideological strategy opposing any cultural expression that does not fit the ethnic, political, or cultural belief system of the speaker [9]. This strategic use of a language could be similar among students with a different ethno-cultural affiliation, which is “not usually seen as empowering the minority language and its speakers by legitimating their practices, but as empowering the majority language and its speakers by reinforcing the use of Spanish at the expense of Basque” [14] (p. 219). Within the Basque Country, two main ethno-national and therefore linguistic factions (Basques and Spaniards) can be found, giving rise to a complex sociocultural context.

The present article thus analyzes the way in which Basque teachers perceive students’ language attitudes and ideological strategies regarding the compulsory use of Euskara, using an online questionnaire answered by 197 in-service teachers. These participants teach in the Southern Basque Country, a region dependent on Spain, composed of two territories: The Basque Autonomous Community (BAC) and Navarre, where both Basque and Spanish are official languages. The two hypotheses proposed in this paper are: (1) teachers perceive that migrant students are not interested in learning Basque and (2) teachers feel Basque is undermined in educational practice.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Euskara as a Minority Language

In 1992, the Council of Europe ratified the “Charter for Regional or Minority languages.” According to this, minority languages are those “traditionally used within a given territory of a state by nationals of that state who form a group numerically smaller than the rest of the state’s population and are different from the official language(s) of that state” [15] (p. 2).

Minority languages are usually at a disadvantage, considering that while hegemonic national languages are compulsorily taught, minority languages might face situations of discrimination from official national authorities [2,3]. Minority languages might also encounter a lack of resources to foster their social use, or even an absence of the required cultural prestige to foster significant numbers of fluent speakers among its own local community [16]. Minority languages are commonly understood as those spoken by an ethnic, cultural or linguistic community that is outnumbered by a hegemonic one and is usually subject to bilingualism [14]. Sharing a common social and cultural space with another hegemonic language can pose a real threat for a minority language, as in the case of the French or Northern Basque Country (Iparraldea), where only 28.4% of the population can speak Basque due to the influence of the French language [17].

The language policies put into practice by the Basque Government, since the creation of the BAC in 1978, made possible the revival, reinforcement and institutionalization of the ancient language of the Basques [2,18]. In Navarre the situation is different, as there are various linguistic areas in which Basque is more or less used. Revival of the Basque language has been possible in northern and middle Navarre, while in the south, Basque is much less used.

Basque was banned during Franco’s dictatorship for almost four decades (1936–1975) in Spain. The prohibition culminated in important migration fluxes from Spain to the Basque Country fostered by the regime mainly during the second half of the 20th Century that made possible the arrival of hundreds of thousands with an ethno-cultural affiliation other than the Basque and weakened the use of the local ancient language in some contexts. The Basque Country has historically been characterized by its unique linguistic, social, and cultural core [9]. Until the second half of the 19th century, many rural areas of the Basque Country continued to maintain a cultural idiosyncrasy anchored in the past. Nonetheless, during the last two decades of the 19th century, it experienced, in the words of MacClancy [19], the fastest industrialization process on the planet. The rich deposits of coal made possible the incipient rise of a heavy industry. As a consequence of the development of the sector, thousands of peasants moved to the more industrialized cities, victims of very poor working and living conditions. These were joined by a high number of migrants from rural Spain. In the words of Eguiguren [20], the proletariat of the Basque Country was mainly made up of Spanish immigrants. Almost all of this emigration was aimed at covering the large number of jobs created by industrialization in the mining and manufacturing area, and it had a great impact in the use of the Basque language both in the social and cultural arena and inside schools as Spanish became the hegemonic language.

Nonetheless, instead of the foreseeable weakening of the emotional connection to the Basque language due to the aforementioned prohibition, its revival was reinforced as people considered this a senseless attack against their ethno-cultural community and cultural and linguistic heritage [21]. In the words of Gurruchaga [3], Euskara rapidly turned into a symbol able to represent the whole cosmology of the Basques. Martínez [2] also points out that Euskara quickly changed into a condensed symbol after its prohibition, and was able to activate strong ethno-cultural affiliations that entailed its own defense [8,20,22]. Bowman [5,6] states that external attacks against ethno-cultural elements, such as language, can lead to resistance in the form of linguistic revival, ethno-cultural awakening, or active political and cultural counter movements. This could explain, to some extent, the defensive behavior of multiple political, social and educational actors when Basque language, or Ikastola-s (Basque schools), are involved [23].

The modern transnational migratory flows arose to a large extent thanks to the democratization of international transport in the end of the 20th Century, summed to the advent of a European Union without physical borders that prioritized the mobility of the workers of its member States. Hence, the profile of the migrant subject arriving in the Basque Country also changed substantially. Migrants arrived therefore not only from Spain, but from the five continents. The existence of this new ethno-cultural melting pot also had its immediate reflection in society and obviously in the Basque educational system composed of public, concerted, and private centers that adapted their curricula to the new challenges, necessities, and goals.

Education remains a primary factor in the regeneration of Basque, and several studies show that this recovery is gradually increasing [16]. The rise in the number of Bascophones in recent years has been ostensible: from 24% in 1991 to 33.9% in 2016 [24]. Urla [25] (p. 13) addresses the aforementioned efforts carried out by the diverse political institutions and sociocultural actors, stating that, “Basques are leaders among minority language advocates in what we could call the total quality turn in language planning.” An important number of experts relate this recovery to efforts carried out by the Basque Government and society in the last three decades to foster and institutionalize the use of Basque as a lingua franca in schools and higher education in the BAC and northern Navarre. A recent study by the Basque Institute of Statistics shows that the use of Basque in education has drastically increased in the last 35 years, from 12.2% in 1983 to 67.6% in 2018 [23]. Similar to the strategies put in motion by the Basque Government in the last four decades, Ladson-Billings [26] proposed the theory of culturally relevant pedagogy in the context of the educational system of the United States, according to which, engaging students, families, and communities at school enables academic success. This directly relates to this paper, as successful teaching practices with minority students have also improved Basque teaching in the post-Franco period.

2.2. Language Learning in the Basque Multilingual and Multiethnic Educational Context

As mentioned above, the Basque Country is currently home to a wide variety of cultures, languages and ethnic groups that comprise a multiethnic society that differs from the past cultural and linguistic homogeneous community [9,16,19,23]. Indeed, the Basque educational authorities are publicly committed to the social, cultural, and linguistic inclusion processes of migrant students [27]. In fact, the BAC has in recent years become one of the preferred destinations for migrants of foreign origin and refugees, as 10.5% of the population is migrant [28]. Similarly, in Navarre, 9.8% of the population is migrant [29]. At this point, it should also be considered the existence of internal and external migration fluxes towards the Basque Country in relation to the existing multilingual context and the specific situation of the students within the Basque education system. The concepts of internal and external migration and not minority ethnic group have been used in the present study as other non-migrant ethnic groups with different characteristics are also part of the Basque society and therefore of the Basque education system, as it is the case of the Basque Roma people. Internal migration makes reference to the migratory processes of Spanish students from other regions excluding the BAC and Navarre, while external migration refers to the aforementioned migrant students coming from foreign countries who enroll in the Basque education system. A student coming from Latin America for instance (external migration), might be in the same linguistic situation as a student coming from another part of Spain, as their mother language in both cases will be Spanish (unless the former was member of an indigenous community with a mother tongue other than Spanish). It is also important to remember the existence of two co-official languages in the Basque Country, Spanish and Basque, both compulsory within the Basque education system. Related literature and research performed in the field also show that migrant students and students with an ethno-cultural affiliation other than Basque, normally enroll in specific education models where Basque is less used, while most local students tend to enroll in models where Basque is the lingua franca [13].

In the BAC, the Basque education system structure divides students into three (and a fourth derived “trilingual system”) linguistic models that are organized in terms of language instruction in either Basque or Spanish. In model A, the language for instruction is Spanish, while Basque is studied as a subject; model B is instructed in both Spanish and Basque; model D (model C does not exist) is instructed in Basque, while Spanish is taught as a subject. In the BAC, most local students tend to choose model D, while migrant students show a tendency to study in models B or A, wherein Basque instruction is minimal, which sometimes leads to ethnic division among classrooms, or even schools, if the proportion of migrant students is high [24]. Model X indicates that Basque is not taught.

Nevertheless, data from a recent study [24] show how this tendency is progressively changing in the BAC (Table 1). While 23.68% of migrant students in secondary school choose to study in Spanish (model A), this figure is 5.92% in primary and 3.86% in pre-school.

Table 1.

Migrant students enrolled in the Basque education system according to the existing linguistic models in the Basque Autonomous Community (BAC).

The education system in Navarre differs, to some extent, to that of the BAC. In Navarre, there are three different areas: (1) the north, or Basque-speaking area, (2) the middle or mixed area, and (3) the south, or non-Basque-speaking area. Different linguistic models apply to each of these areas. In the Basque-speaking area it is compulsory to instruct in Basque (models A, B, or D), whereas in the mixed (models A, B, D, and G [called model X in the BAC]) and non-Basque-speaking (models A, D, and G) areas, Basque instruction is not compulsory [30]. Data about the distribution of migrant students in Navarre have not been published; hence, these could not be included in this study.

2.3. Teachers’ Perceptions when Teaching Minority Languages

Teachers are central for students to develop adequate language competence. Key elements affecting student learning include the quality of explanations provided during lessons, the design of each intervention, and assessment [31,32]. The quality of these elements is directly influenced by teachers’ perceptions during classroom interactions. In this context, teachers’ perceptions refer to the feelings and beliefs teachers have while teaching. If teachers’ perceptions are positive, teaching will produce better results than if the perceptions are negative [33,34]. This is commonly referred to as teacher satisfaction, which González-Riaño and Arnesto-Fernández [33] analyze in a study focusing on teachers’ satisfaction in the teaching of Bable (the local language) in Asturias. Asturias is a region located in the north of Spain, where Bable is a minority and endangered language in relation to Spanish. The teaching of Bable is not compulsory in the education system and teachers working in villages have positive attitudes toward the learning of Bable in primary education, in contrast to towns, where working conditions and the status of Bable is almost marginal. The perceptions of teachers in secondary education are worse, as students coming from bilingual backgrounds and speaking both Bable and Spanish do not achieve high linguistic performance in any of the languages. Teachers in this study believe that the compulsory instruction of Bable could improve students’ competence in both languages. These conclusions are corroborated by Rodríguez-Álvarez [34], according to whose study instruction of Bable at school is very low, as linguistic and education policies do not reinforce its classroom use. The study argues that the lack of reinforcement of Bable in compulsory education is remarkable in relation to other autonomous communities in Spain, such as the Catalan or the Basque Autonomous Community, where Catalan and Basque, respectively, officially coexist with Spanish.

In Catalonia, various studies have been conducted to analyze the learning of Catalan in schools [35,36]. Based on the focus of the current paper, two studies carried out in an ethnically and linguistically diversified Catalan high school are relevant. In a study by Trenchs-Parera and Newman [34], adolescent language attitudes toward Catalan and Spanish were presented in two different groups. These attitudes were categorized according to the level of support of Catalan or Spanish and related to identity construction. One research group was composed of local students and the other of Latin American migrant students. The results of the investigation indicate that local students had clear language attitudes in relation to Catalan. According to the authors, local students’ language attitudes ranged from six different “ideological stances along a spectrum from most “catalanista” to most “españolista” and more cosmopolitan and mixed Spanish and Catalan middle-ground attitudes” [34] (p. 512). These terms express the link within each individual between language and identity; whereas “catalanista” indicates greater identification with Catalan language and identity, “españolista” indicates greater identification with Spanish language and identity. Latin American students’ language attitudes were not as clearly divided along the ideological spectrum of “catalanista” and “españolista”; these students were more prone toward protecting their Spanish variety and showed negative attitudes toward Catalan. Teachers in this study reported that more Catalan teaching hours would be needed to adequately respond to the linguistic needs of their migrant students and promote more positive attitudes toward Catalan. Similarly, in the Basque Country, there have been Basque revitalization and normalization efforts since the 1970s [37,38,39]. Tejerina [40] suggests that in the 1980s and 1990s Basque society witnessed a progressive institutionalization of the Basque cultural and linguistic movement. This institutionalization took place in two ways: on one level was increasing awareness concerning the relationship between language recovery and collective identity; on a second, structural level progressive institutional control of the ethno-linguistic movement occurred.

In a study by Valadez et al. [39], higher education students taking an education degree, and in-service teachers in the Basque Country, were asked about their language perceptions. In this study, the authors analyze how these teachers and future educators perceive Basque revitalization in linguistically and ethnically diversified schooling contexts. The study concludes that students perceive immigration as positive for Basque normalization. In other words, according to the teachers, the presence of migrant students does not interfere with the process of Basque revitalization.

In another Basque-based study, Arozena et al. [41] compared teacher perceptions of teaching the minority language in the Basque and Frisian setting. The study found that Basque teachers showed positive attitudes towards teaching in Basque, while teachers of Frisian showed more negative beliefs. This indicates that attitudes towards teaching minority languages could be context oriented.

In the context of Israel, Dubiner et al. [42] analyzed teacher perceptions in a Hebrew-Arabic bilingual program, where Arabic is the minority language. The study concluded that positive teacher attitudes and interventions using the minority language is crucial for the inclusion of both minority and majority languages in bilingual education programs. Similar conclusions have reached other studies, for instance, in the Irish case teaching Irish minority language, Ó Murchadha and Flynn [43] state that teachers are key in reinforcing Irish and its varieties in the schooling setting.

In this sense, a study by Glock, Kovacs and Pit-Ten [44] within school multilingual contexts in Germany, points out the importance of the relation between teachers’ working experience and their perception over their students. The authors affirm that preservice teachers imagining a more culturally diverse school held more negative implicit attitudes towards ethnic minority students than those imagining a less diverse school. In contrast, in-service teachers actually working in more diverse schools held less negative implicit attitudes towards minority students. In this regard, a survey done by the Basque Government [45] to school boards on how well were primary and secondary school teachers prepared to teach to migrant students, showed that 66% of the member of the primary school boards and 63% of the secondary school boards think teachers are very well prepared to teach to migrant students.

This idea is also reinforced in the study carried out by Paciotto [46] with the Slovene linguistic minority in Italy. Paciotto points out the idea that teachers’ and students’ language attitudes, ideologies and perceptions have permitted the language minority-based schools to persist and function as a viable alternative to the national mainstream schools in Italy.

The perception teachers’ have about their students in American multilingual schools is deeply relevant in words of Blanchard and Muller [47], who affirm that language-minority students born in the U.S. are more likely to be negatively perceived. The authors underline the importance of considering both language-minority and migrant status as social dimensions of students’ background that moderate the way that high school teachers’ perceptions shape students’ preparation for college.

Taking into account the findings presented, the research questions are:

- (1)

- What are the reasons for students to complain when learning Basque, the issues related to the teaching in Basque, and teachers’ possible solutions?

- (2)

- How are complaints against Basque performed (i.e., do students ally to avoid studying Basque)?

- (3)

- Is there any relation between the origin of the students, the teachers’ working experience and the teachers’ working region with the occurrence of issues, type of complaints in class and the role of their parents?

3. Methods

The present research was designed using a quantitative method to study Basque teachers’ perceptions of teaching Basque to students with different ethno-cultural and national backgrounds within multiethnic and multilingual classrooms. To this end, 197 teachers answered a survey composed of 21 items (see Appendix A). In order to carry out the study, the researchers distributed online surveys among teachers providing service in the BAC and Navarre, in areas where Basque is officially and compulsorily taught.

3.1. Tools

An opinion questionnaire about teachers’ perceptions of students’ behavior toward their teaching and the use of Basque was organized by a research team within the Faculty of Education at the University of the Basque Country in 2018. Questions were designed following the findings by González-Riaño and Armesto-Fernández [33], as it was not possible to find any validated survey which suited our aims. The questionnaire had a total of 21 items related to the use of Basque while teaching lessons, and possible situations of misbehavior and opposition to it (see Appendix A).

Most of the proposed items had several possible answers by which the variables could be determined, such as the level of motivation, the opposition to Basque learning and teaching processes, and other behavioral issues related to the different spheres of the students’ daily lives, and individual and social identities. The questionnaire was created using Encuestafacil, a professional online tool utilized by the University of the Basque Country. The 21-item questionnaire was then distributed using this tool via a social network made up only by teachers from the BAC and Navarre. All 197 teachers who were part of this network fully answered the survey.

The questions in the survey sought to obtain specific information about different aspects related to the perceptions teachers had when teaching local languages to migrant students. Most questions were closed, but some had the possibility of adding a short explanation (though this could also be interpreted in a quantitative way). The most relevant questions in terms of the obtained data, and addressing the perceptions of teachers when teaching in Basque, involved dealing with problems when teaching the language to ethnically diversified audiences. The survey also included some questions related to the kinds of problems that arose during class, whether students complained about having to learn Basque, and the ethnic origin of these particular students (see Appendix A).

3.2. Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis of the multiple-choice questions was performed, and the frequencies of the answers and their percentages related to the number of teachers that answered the question were calculated.

To study the relation between the teachers’ perceptions of students’ linguistic attitudes toward Basque, the origin of the students, the teachers’ working experience, the teachers’ working region, the role of the students’ parents, the occurrence of issues and complaints in class, type of issues and forms of student opposition chi-square analyses were conducted on the following: Origin * Issues (8)/Origin * type issues (9)/Origin * Compains (11)/Origin * Complain why (14)/Origin * Stand (15)/Origin * Friends (16)/Origin * Only Basque (17)/Origin * Solution (18)/Origin * Parents (19)/Years * Issues/Years * Complaints/Years * Parents/Place * Issues Place * Complaints. All analyses were conducted using SPSS® (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) statistical software package (version 23, IBM® Company, Armonk, NY, USA).

To analyze the types of issues related to the teaching of Basque, several histograms were created, comprising reason(s) to complain, reason(s) for behavior, and possible solutions. The study also considered how complaints were conveyed, whether students tended to avoid studying Basque, and whether negative attitudes were due to other factors such as family influence. Pie charts were created to present the results. For this purpose, Microsoft® Excel® (Microsoft Corporation 2016©) was used.

4. Results

A total of 197 teachers who worked in regions where Basque is a co-official language (BAC and Navarre) responded to the questionnaire (Table 2). All participants taught in Basque language and had at least a Basque advanced language profile (C1) in the European frame. Childhood or primary-level educators comprised 56% (111) of the respondents, while 44% (86) taught in secondary education. Regarding teaching regions, most participants taught in Gipuzkoa (71/36%) or Biscay (69/35%). Basque language teachers amounted to 48.2% (95), and 50.3% (99) had fewer than five years of teaching experience.

Table 2.

Profile of the surveyed teachers (n/%).

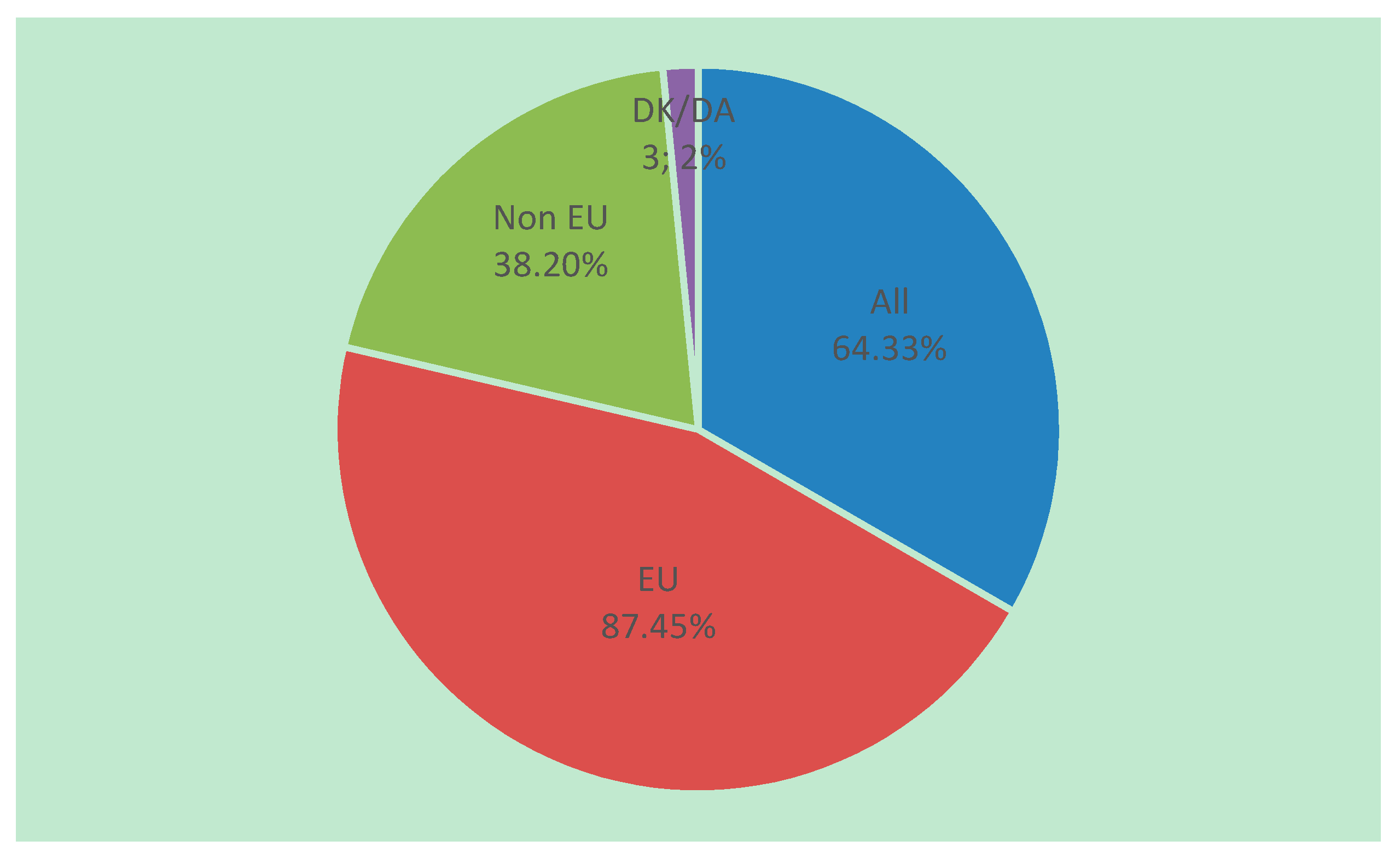

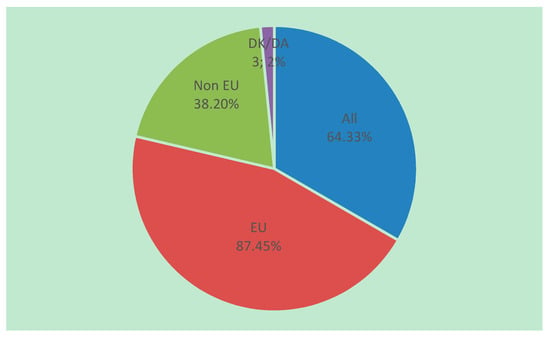

With regards to the origin of the students, 45.3% of the teachers said they only had European students in their lessons, 33% had students from different origins, including European, 19.8% only had migrant students, and 1.7% of the teachers did not answer this question (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The origin of students according to teachers. Non-EU; Latin American, Maghreb, African and/or Asian. EU; European, All; Non-European Union and European.

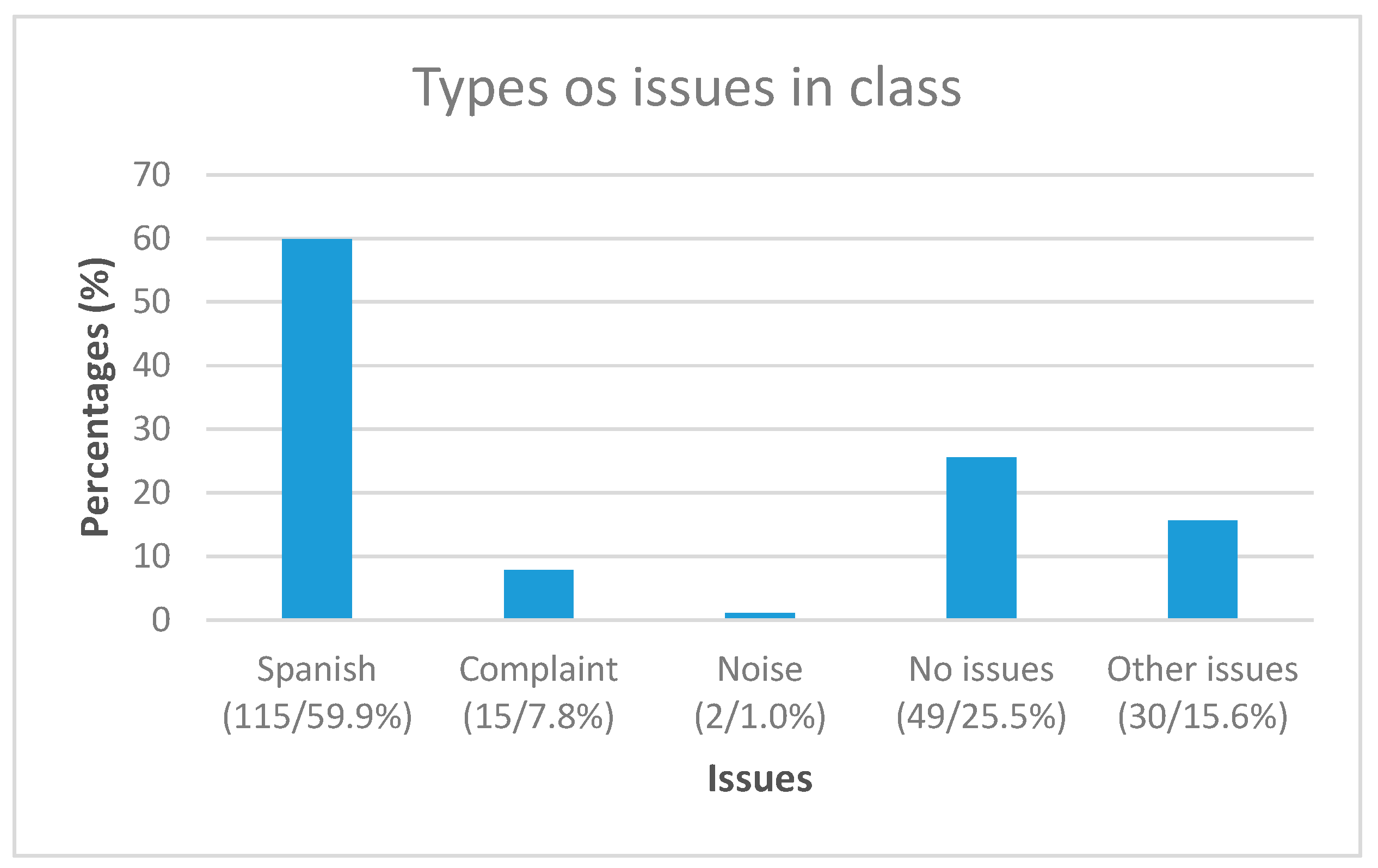

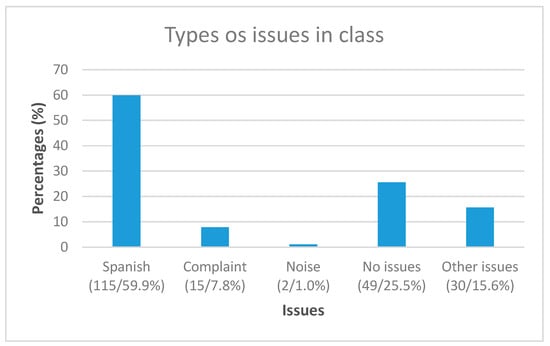

Regarding the use of Basque language in class, 61.4% of the teachers reported having some issues with students. The most frequent issue reported by teachers (115/59.9%) was speaking Spanish during classes in which Basque is supposed to be the curricular language (Figure 2). Other issues were complaints (15/7.8%), making noise (2/1.0%) and other issues (30/15.6%). Very few (15/7.1%) teachers said that their students complained about the use of Basque in class, and 49/25.5% of the teachers declared that they did not have any problem related to the use of Basque. There was no relation between the occurrence of issues in class and the origin of the students (Basque, Spanish, European, non-European, and mixed students), or with the region in which the teachers worked (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Types of issues reported by teachers. 192 teachers answered this question, and the number of answers was 211. (Raw data of answers/percentage number of answers vs. number of teachers answering the question).

Table 3.

Chi-square analysis results.

A significant relation between teachers’ working experience and the occurrence of issues in class was found (Table 3). The chi-square analysis showed that, less experienced teachers (<5 years) tended to report more problems when teaching in class, due to the use of Basque language in class comparing to hose more experienced (>5 years).

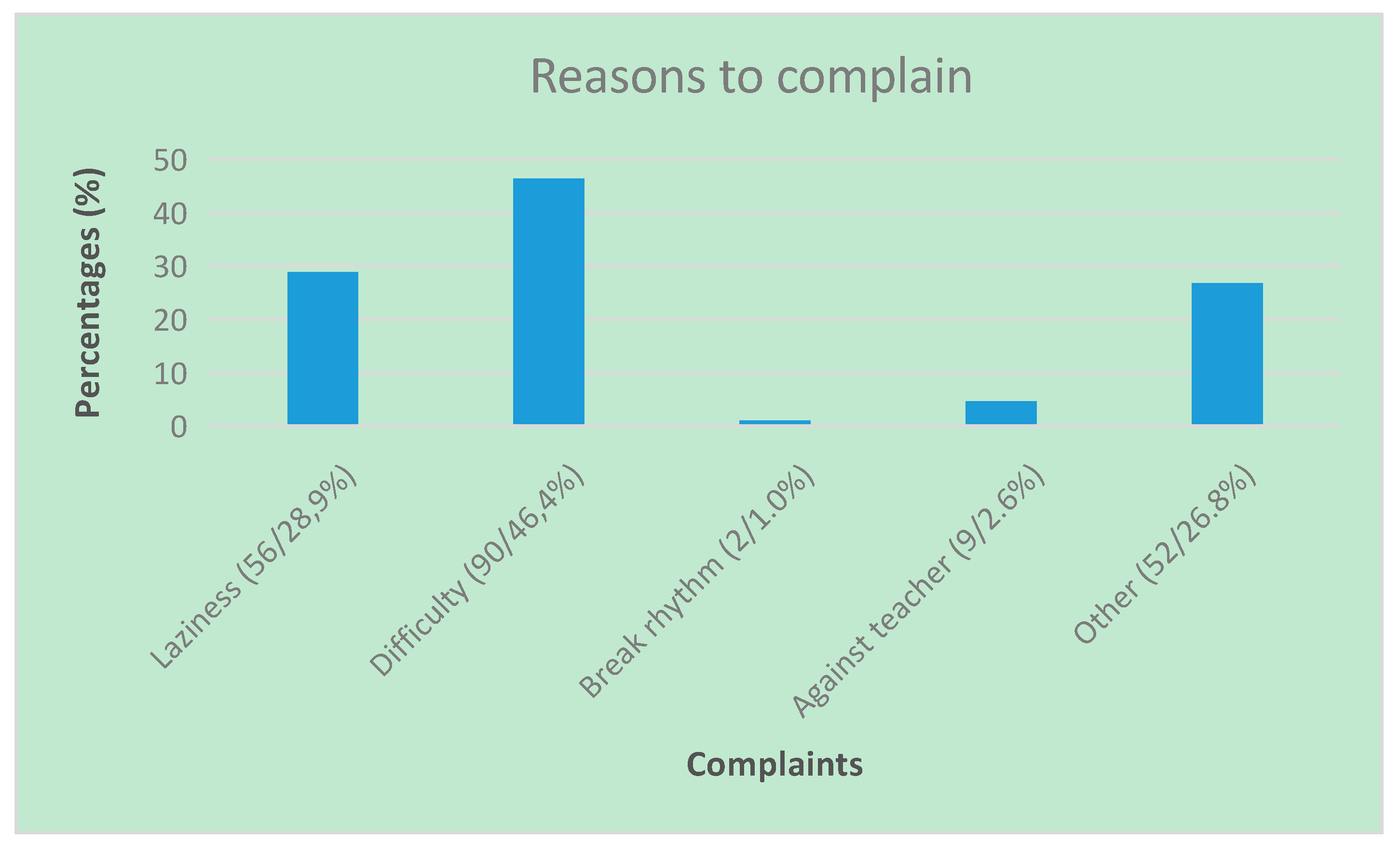

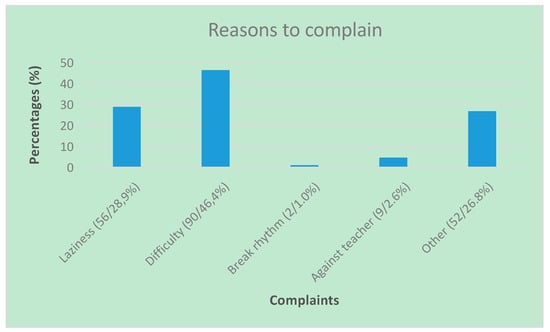

With respect to complaints, 61.4% of the teachers reported that students complained about studying in Basque. Almost half (90/46.4%) of the teachers thought that students normally complained because they felt that Basque is difficult, and 28.9% (56) also thought it was related to the students’ laziness (Figure 3). There was no relation found between the origin of the students, the teachers’ teaching experience, the region teachers worked in, and the occurrence of complaints (Table 3).

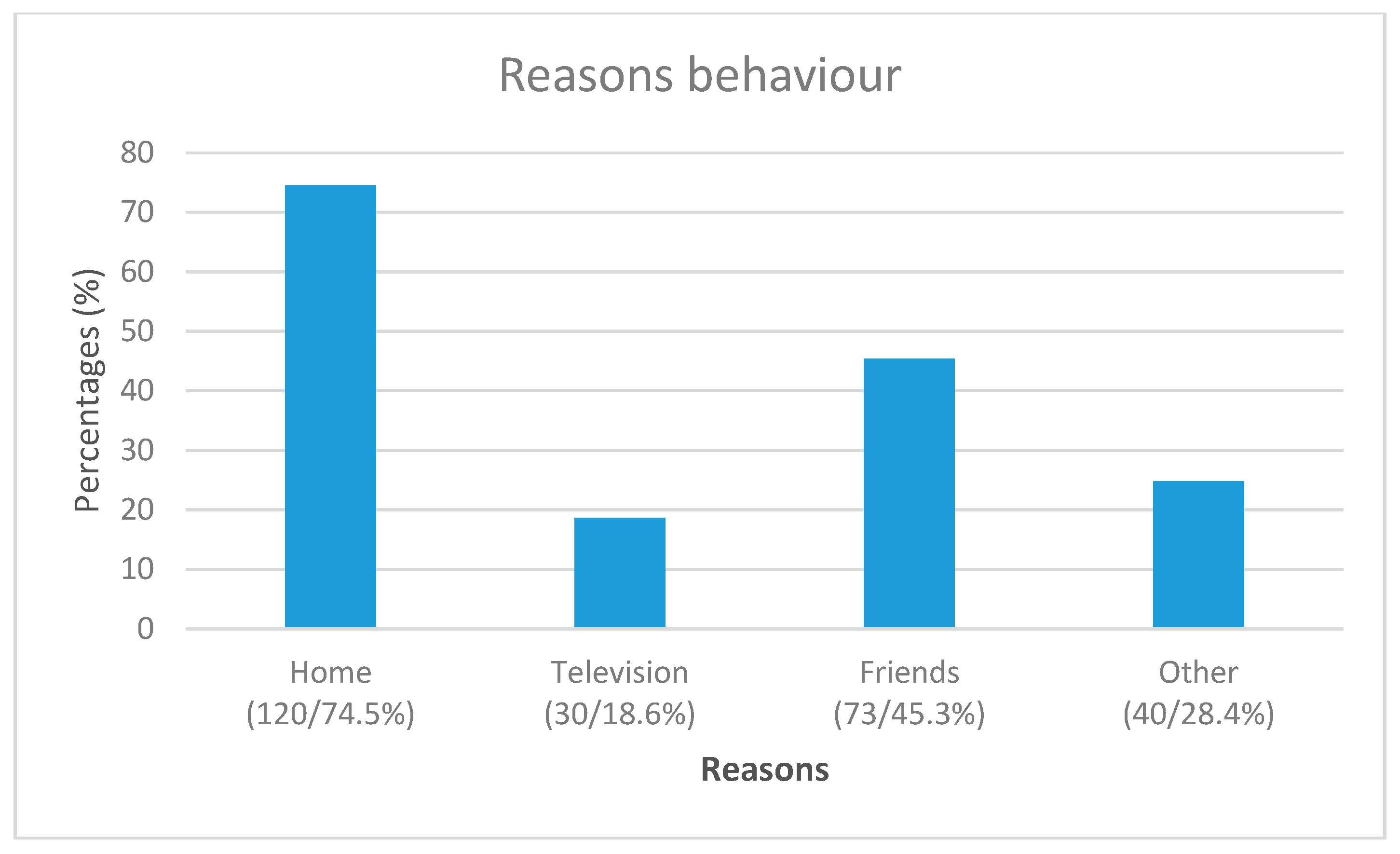

Figure 3.

Reason to complain about studying in Basque language. 194 teachers answered the questions and the number of answers was 209. (Raw data of answers/percentage number of answers vs. number of teachers answering the question). The participants considered the main reason for the students having a negative attitude toward Basque language was the messages they received at home (120/74.5%). Teachers also considered that friends (73/45.5%) and television (30/18.6%) influenced students’ behavior toward the Basque language. When asking whether parents negatively influenced students’ perceptions of the use of Basque, 99.5% of the teachers answered affirmatively (Figure 4).

The present study also focuses on the origins of the students within the surveyed teachers’ classrooms, in regard to their answers to the present survey, as these could differ from each other. Nonetheless, data showed there were not significant differences in their answers due to teaching in classrooms with a different typology in relation to students’ origin (only European, Non-European and both) (Table 3).

There was no relation between the region and the occurrence neither of issues, nor between the region and the occurrence of complains (Table 3).

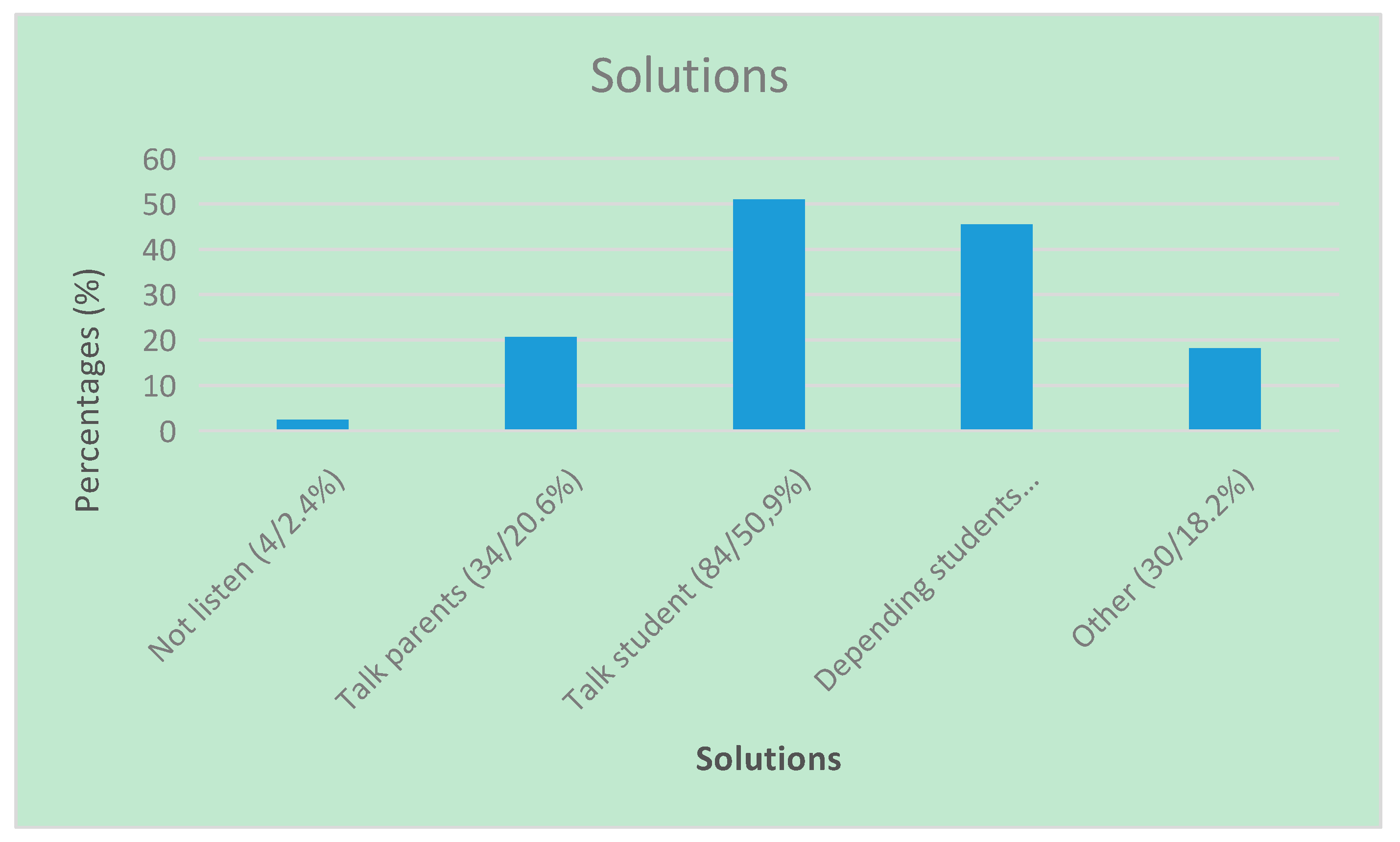

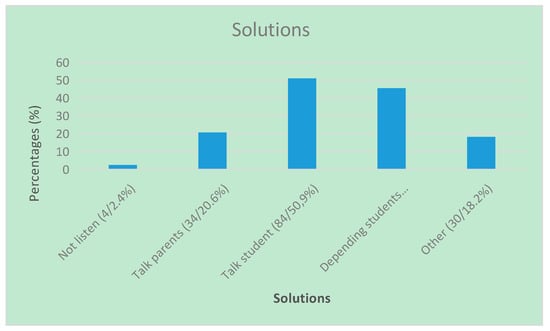

Half (84/50.9%) of the surveyed teachers reported that the best solution to problems was to talk to the students, while 20.3% (34) selected talking with parents (Figure 5). For 45.5% (75) of respondents, the solution involved adapting to the student.

Figure 5.

Teachers’ solutions to students’ negative attitudes toward the Basque language. 165 teachers answered, and the number of answers was 227. (Raw data of answers/percentage number of answer vs. number of teachers answering the question).

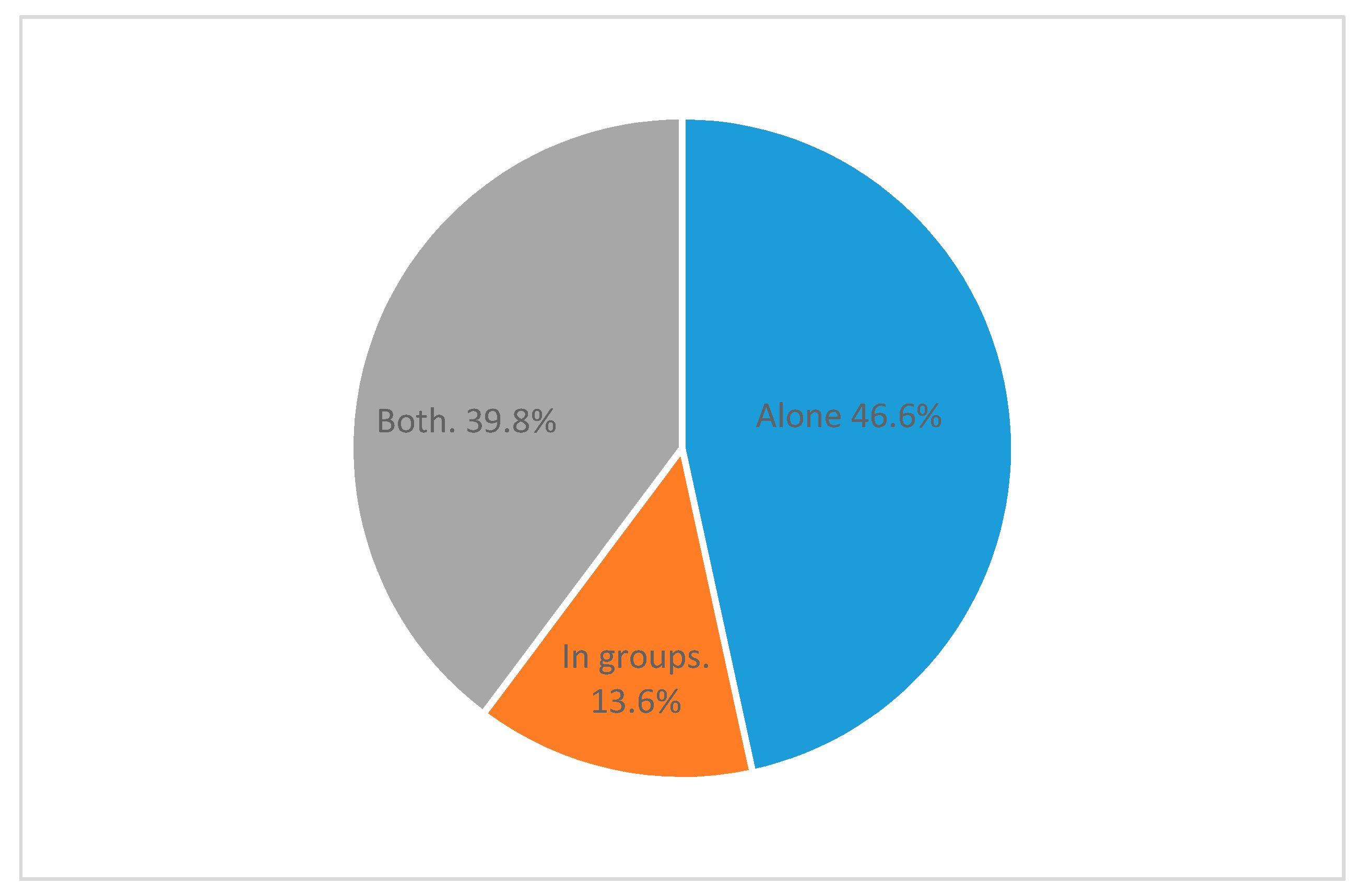

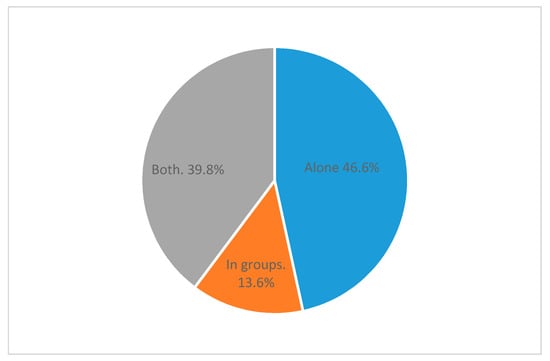

In regard to student misconduct when learning in Basque, 46.6% (41) of the teachers affirmed that students opposed teachers alone, 13.6% (12) in a group, and 39.8% (35) both in a group and alone (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forms of student opposition to teachers when Basque is used. 88 teachers answered and the number of answers was 88.

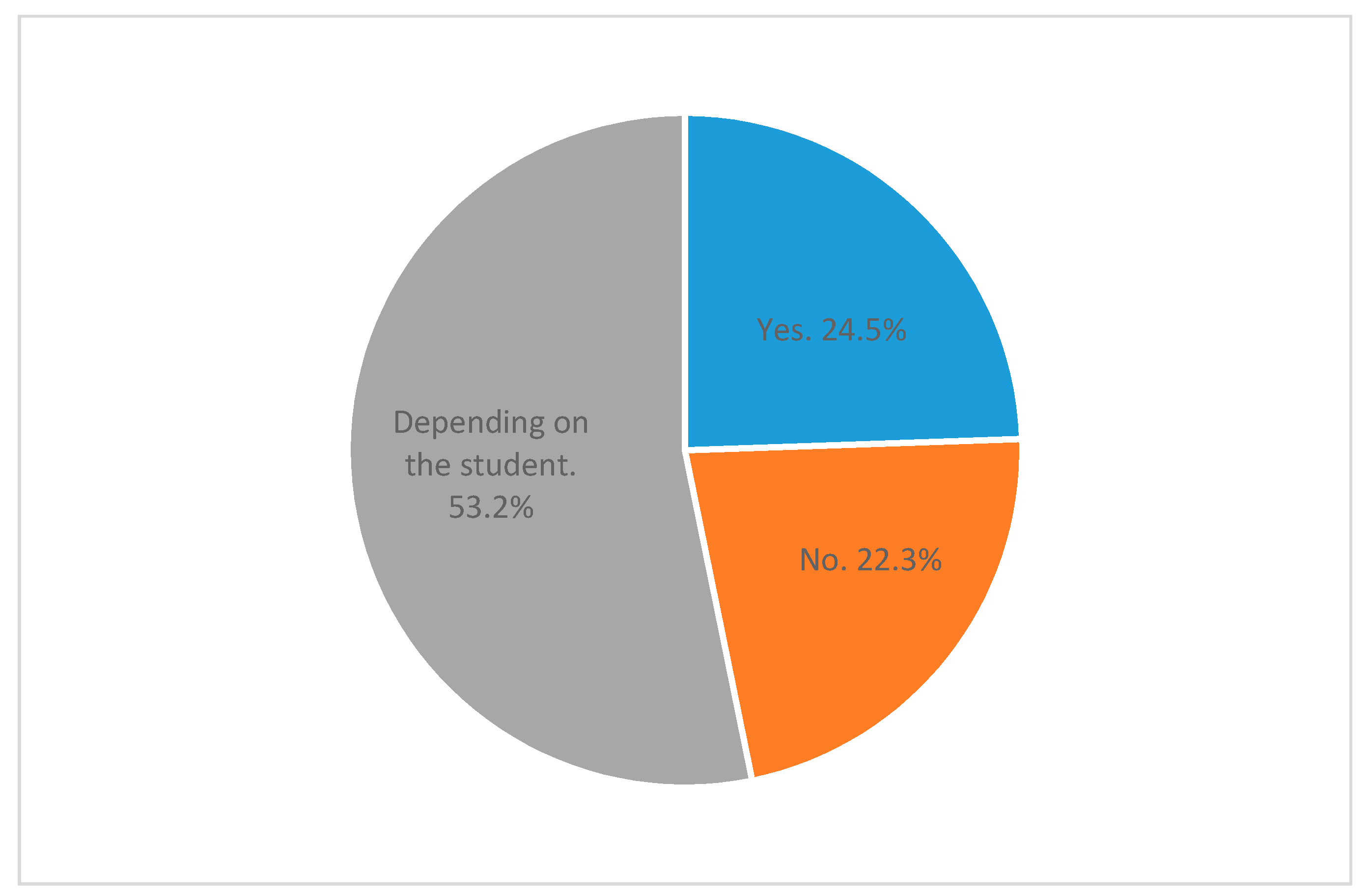

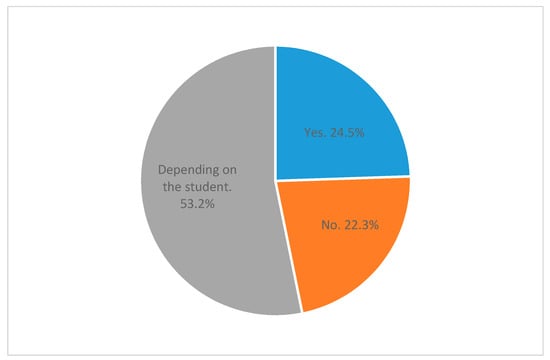

When teachers were asked about the reasons for student opposing Basque, most answered that they did not know (50/53.2%); while 24.5% (23) responded that it was because the students were friends, nonetheless 22.3% (21) denied this (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Students’ opposition (in groups) against the teacher when Basque is being used. 94 teachers answered, and the number of answers was 94.

5. Discussion

A number of conclusions can be deduced from the results presented in the previous section. Nonetheless, some run counter to initial expectations, as data showed that, according to teachers’ perceptions, migrant students did not present specific problems or issues compared to local students when teaching Basque in the classroom.

5.1. The Issues Related to the Teaching of Basque

As mentioned above, various studies [13,31,32] suggest that migrant students might present challenges when it comes to the teaching of certain subjects. In this sense, second languages are normally situated in the core, considering the difficulties they entail for migrant students. Learning a new language also means learning an entirely new social and cultural cosmology [48,49], which normally also leads to new ethno-symbolic landscapes and arenas. In this sense, the abovementioned study carried out by the Basque Government in 2016 [45] also points out that migrant students face barriers related to their education processes due to the learning of local languages (83.1%), Basque and Spanish, rather than because of cultural (52.3%) or religious aspects (17.8%).

As also stated above, students can oppose the learning of some co-official but non-hegemonic languages such as Basque for various reasons. This opposition could be a sign of rejection of certain ethno-cultural systems, represented by local languages, cultural expressions or traditions [50]. Nonetheless, local students who might have a different ethno-cultural affiliation can also oppose some arenas more actively than others, and migrant students may not oppose any at all. In some contexts, opposing and confronting language teachers could also be interpreted as a sign of identity praise (cultural, linguistic, and political), rather than an act of misconduct, misbehavior or transgression [9,10].

Studies [16,23] state that Basque language teachers are normally more committed to the well-being of the Basque language and culture compared to other social actors. Thus, their perceptions regarding students’ behavior toward the use of Basque could be influenced by this fact. Various data and some of the aforementioned studies lead us to believe that these phenomena are common in complex linguistic, cultural, political and social societies such as that of the Basque Country.

The Basque Country was home to the last armed ethno-national conflict in Europe. This deep-rooted dispute had direct consequences and influence on every aspect of the local cultural, linguistic and social arena, because all have been at some point been politicized [2,3,19]. As a result, two main ethno-national factions (Basques and Spaniards) can be found within the Basque Country’s complex sociocultural context.

Migrant students usually arrive in the Basque Country with their own ethno-cultural capital and political affiliation, which is not necessarily opposed to the Basque one. In fact, and according to the data sourced from our surveys, migrant students from foreign countries might not have specific issues with the learning of Basque based on ethno-cultural or political reasons. Trenchs-Parera and Newman [35] state that migrant students’ language attitudes are not as consistent and clearly differentiated in terms of local ethno-cultural and political affiliation (Basque vs. Spanish), while their concerns and negative attitudes when learning a local language are more related to their own interests and cultural backgrounds.

In relation to the first research question, the data obtained in this study show that, from the teachers’ perspective, there is no relation between the occurrence of issues, misconduct or misbehavior during Basque lessons and the origin of students. For the teachers, the most frequent problem in their Basque language and literature lessons was the students speaking Spanish (59.9%). In addition, 25.5% of the teachers declared they did not have any problem related to the use of Basque during their lessons.

5.2. Teachers’ Working Experience and Family Influence

In relation to the third research question, the findings show a relation between the work experience of the teachers and the occurrence of issues in class. Teachers with less experience tended to report more problems than did those with more experience. A study carried out by the Basque Government in 2016 concluded that teachers with more teaching experience do not report as many incidents as do teachers with less teaching experience. Nevertheless, the reported situations were not directly related to the origin of the students involved. Moreover, recent studies [39] show that Basque teachers do not perceive migration and the presence of migrant students in schools as a negative factor for Basque normalization.

Of the teachers in this study, 64% affirmed that their students often complained about the obligation to learn Basque, and 55% also explained that the main reason for these complaints pertained to difficulties in learning a local language.

Personal interests that students convey in opposing the use of Basque during lessons may also be influenced by their parents’ own interests, according to the teachers we surveyed. Several studies [16,23] state that migrant students and students with ethno-cultural affiliations other than Basque might be negatively influenced by their parents regarding their attitudes or perceptions concerning the use of the Basque language in their everyday lives.

The data obtained in this study reveal that, according to the surveyed teachers, one of the most important reasons for students having attitudes against the Basque language pertained to the role of their parents regarding the use of a certain language (74.5%). The teachers also considered that friends (45.5%) and television (18.6%) negatively influenced their students’ opinions and use of the Basque language when communicating. In fact, when teachers were asked about their opinion on the origin of students’ negative attitudes regarding the use of Basque, 99.5% answered that these opinions originated “at home.” The results were extremely clarifying if we consider that when teachers and students have positive perceptions, teaching yields better results than if attitudes are negative [31,32].

5.3. Students’ Complaints against Basque

In relation to the second research question, a total of 25% of the surveyed teachers declared that complaints were posed by students individually, while 29% stated that they were conveyed by students in a group. These alliances [13] students formed were normally constituted in opposition of the use of Basque. 45% of the surveyed teachers affirmed such groups comprise friends that share the same ethno-cultural affiliation (Spanish or other). Nonetheless, according to the data, the complaints were not necessarily carried out as part of a group sharing the same ethno-cultural background. In other words, students do not necessarily ally to oppose their teachers and the learning of Euskara (Basque language) merely based on their ethno-cultural affiliations, but also for prioritizing their own personal interests. This is contrary to findings of Roman and Pérez-Izaguirre [13].

5.4. Students’ Origin and Teachers’ Perceptions in the Survey

Regarding the possibility of a certain influence over the teachers’ perception towards their students, and therefore the possibility of facing substantial changes in their answers deeming the typology of their classrooms and origin of the students (only European, Non-European and both), the compiled data showed there was not such influence and teachers’ answers did not differ based on the aforementioned typology.

6. Conclusions

One main outcome of the present study is that opposition to using Euskara during school lessons by migrant and local students is not necessarily linked to students’ negative attitudes. Conversely, according to teachers, these attitudes have been internalized and embraced at home.

Regarding the hypotheses, hypothesis 1, “teachers perceive that migrant students are not interested in learning Basque,” is refuted, as teachers did not relate the origin of students to their attitudes toward Basque, while hypothesis 2, “teachers feel Basque is undermined in educational practice,” is partly validated, as some teachers acknowledged that students complain when learning Basque. Some of the misconduct related to these complaints was the use of Spanish during lessons in Basque.

A limitation in this study is that a difference was not made between internal and external migration in the questionnaire, neither to students’ own political stances. Hence, future research should study whether opposition to the use of Basque is related to students’ ethno-cultural and political affiliations, or related to other factors. It should also study whether lower academic achievement in the Basque case is related to negative attitudes toward Basque, as per the study by González-Riaño and Arnesto-Fernández [33] regarding Bable. For this, the study should be extended to students’ feelings and perceptions, which would include a data collection with students themselves. Future research should also address the impact of teaching methods in Basque teaching.

Regarding teachers’ perception on the attitudes their students might have when opposing to the teaching of Basque, further research should also consider the educational context where the teaching is carried out as this could influence both, teachers’ perceptions and students’ attitudes towards Basque.

It is also recommended for a future research to extend the present study from the perspective of a critical pedagogy when analyzing the reasons students and their parents might have when opposing to the teaching of Basque, A recent study by Garcia et al. [51] points out the idea that ethnolinguistic identity plays a more relevant role in explaining socio-linguistic attitudes in traditional Basque-Spanish contact, than attitudes related to emerging contact with new immigration.

This study also makes a contribution at an international level as teacher perceptions are fundamental to understand and enhance their relationship with students while teaching minority languages, in line with the studies by Dubiner et al. [42] and Paciotto [46]. As in the study by Glock et al. [44], it also points out that teaching experience may be related to these perceptions. It also points to families as key to understand the negative attitudes students might have towards the use of minority languages. Pujolar [52] points out the idea that migrant students and their parents might find that discourses and linguistic practices in different contexts diverge as to the ways in which they are expected to fit into the local linguistic arena, and for that reason in many immigrant homes, the children learn a minority language (Catalan) at school while their parents learnt the hegemonic one (Spanish) in their workplace and daily routine.

Future studies should focus on the role of families’ influence over students and the learning of minority languages in other research settings, as this would enable a more exhaustive international comparison.

Overall, this study analyzed teachers’ views when teaching Basque to multiethnic audiences in the BAC and Navarre, and contributes to the theory of minority language learning in contexts such as Basque. This study provides evidence that can be used by education stakeholders regarding teachers’ perceptions of Basque education when teaching Basque to an ethnically and linguistically diverse audience. The results could also be used to design more effective language lessons and better communication with students’ families.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.R.E. and E.P.-I.; methodology, A.L.-R.; software, A.L.-R.; validation, G.R.E., E.P.-I. and A.L.-R.; formal analysis, A.L.-R.; investigation, G.R.E.; resources, E.P.-I.; data curation, A.L.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.R.E.; writing—review and editing, G.R.E., E.P.-I. and A.L.-R.; visualization, G.R.E. and E.P.-I.; supervision, G.R.E.; project administration, G.R.E. and E.P.-I.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Gorka Roman Etxebarrieta would like to acknowledge the support received by his research group, KideOn, and Elizabeth Pérez-Izaguirre would also like to acknowledge the support received by her research group Ethics in Communities of Practice Research Team at the University of the Basque Country (ETICOP-IT, GIU 18/140).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Questionnaire

1.-Students’ attitude towards Basque

1. What level do you teach?

- (a)

- Primary Education

- (b)

- Secondary Education

- (c)

- Vocational Training

- (d)

- Other (Please specify)

*2. In what geographical area do you teach?

- (a)

- Alava

- (b)

- Gipuzkoa

- (c)

- Bizkaia

- (d)

- Navarre

- (e)

- Other (Please specify)

3. In what region do you teach?

(open-ended question)

4. Are you a teacher in Basque?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- (c)

- Does not know/ Does not answer (DK/DA)

5. How many years have you spent as a teacher?

- (a)

- 0–1

- (b)

- 1–5

- (c)

- 5–10

- (d)

- 10–15

- (e)

- 15>

6. Do you teach your classes in Basque?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

7. What is your language profile?

- (a)

- PL0

- (b)

- PL1 PL2

- (c)

- Other (Please specify)

- (d)

- DK/DA

8. Do you normally have problems teaching your classes in Basque?

- (a)

- Never

- (b)

- Sometimes

- (c)

- Often

- (d)

- Always

- (e)

- DN/DA

9. What kinds of problems do you normally have?

- (a)

- I have no problem and the students are fluent in Basque.

- (b)

- Students speak and respond to me in Spanish.

- (c)

- Students complain about the use of Basque.

- (d)

- When I speak in Basque, the students make noise.

- (e)

- Other (Please specify)

10. What is the ethnic origin of your students in general?

- (a)

- Latin American

- (b)

- Maghreb

- (c)

- European

- (d)

- African

- (e)

- Asian

- (f)

- Other (Please specify)

11. Have students ever complained about having to learn Basque?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- (c)

- Sometimes

- (d)

- Often

- (e)

- DK/DA

12. Do local students complain about having to learn Basque? Explain briefly.

(open-ended question)

13. Do migrant students complain about having to learn Basque? Explain briefly.

(open-ended question)

14. Why do you think they complain about the use of Basque?

- (a)

- Because they find it difficult.

- (b)

- To break the pace of the class.

- (c)

- To oppose the teacher.

- (d)

- For pure idleness.

- (e)

- Other (Please specify)

15. When students are in Basque lessons, do they stand alone or do they come together?

- (a)

- Alone

- (b)

- Group

- (c)

- Both

- (d)

- DK/DA

16. Does it happen because they are friends?

- (a)

- Yes.

- (b)

- No.

- (c)

- Depending on the situation.

- (d)

- Other (Please specify)

- (e)

- DK/DA

17. Do they usually come together only to oppose Basque?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- (c)

- Depending on the situation

- (d)

- Other (Please specify)

- (e)

- DK/DA

18. What do you think is the best solution to address this problem?

- (a)

- Play dumb

- (b)

- Meeting Parents

- (c)

- Talk to the students

- (d)

- Depending the student

- (e)

- Other (Please specify)

- (f)

- DK/DA

19. Do you think that the role of parents in the attitude against Basque is important?

- (a)

- Yes

- (b)

- No

- (c)

- Other (Please specify)

- (d)

- DK/DA

20. Where do you think the attitude towards Basque arises?

- (a)

- At Home

- (b)

- TV

- (c)

- Friends

- (d)

- Other (Please specify)

- (e)

- DK/DA

21. What do you think is the origin of negative attitudes that may arise against teachers at school? Explain briefly.

(open-ended question)

References

- Roman, G. The War of the Symbols: Performative Violence within the Black Bloc and Kale Borroka. In Rethinking Peace and Security. New Dimensions, Strategies and Actors; Duarte Lopes, P., Ryan, S., Eds.; University of Deusto: Bilbao, Euskadi, 2009; pp. 83–92. ISBN 9788498302356. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, J. La Construcción Nacional de Euskal Herria. Etnicidad, Política y Religión (The National Construction of the Basque Country. Ethnicity, Politics and Religion); Ttarttalo Argitaletxea: Donostia, Spain, 1999; ISBN 84-8091-547-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gurruchaga, A. El Código Nacionalista Vasco Durante el Franquismo (The Basque Nationalist Code during Franquism); Anthropos: Barcelona, Spain, 1985; ISBN 8485887786. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholtz, M.; Hall, K. Language and Identity. In A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology; Duranti, A., Ed.; 2004 Oxford; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1405144308. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, G. The Violence in Identity. In Anthropology of Violence and Conflict; Schmidt, B., Schroeder, I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; pp. 37–58. ISBN 978-0415229067. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, G. Constitutive Violence and the Rethorics of Identity: A Comparative Study of Nationalist Movements in the Israel-occupied Territories and Former Yugoslavia. Soc. Anthropol. 2003, 3, 118–143. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, G. El Rock Radical Vasco: La Constitución de los Sujetos Políticos a Través de la Música. Inguruak 2018, 64, 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Filibi, I. La Dimensión Exterior de la Autonomía Vasca: Apuntes Sociojurídicos sobre las Euskal Etxeak (External Dimension of Basque Autonomy: Sociojuridical notes about Euskal Etxeak). Unpublished material. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, G. El Deseo Nacional: La Gramática del Surgimiento de los Sujetos Nacionales (National Desire: The Grammar of the Creation of National Subject); University of the Basque Country: Leioa, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hage, G. The Spatial Imaginary of National Practices: Dwelling, Domesticating, Being-Exterminating; Sydney University: Sydney, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yon Tao, L. Discourse, Meanings and IR studies: Taking the Rethoric of “Axis of Evil” as a Case; Fudan University: Guadalajara, México, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concept of Pollution and Taboo; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-0415289955. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, G.; Pérez-Izaguirre, E. Identidades Efímeras: Análisis de Estrategias de Alianza Etnolingüística en Sistemas Educativos Multiculturales (Ephemeral Identities: Strategies of Ethnolinguistic Alliances in Multicultural Education Systems). In Lenguas, Patrimonio e Identidades. Perspectiva Educativa; Naya, L.M., Chateaureynaud, M.A., Dávila, P., Eds.; Delta Publications: Kiel, WI, USA, 2018; pp. 315–322. ISBN 978-84-17526-15-3. [Google Scholar]

- Leonet, O.; Cenoz, J.; Gorter, D. Challenging Minority Language Isolation: Translanguaging in a Trilingual School in the Basque Country. J. Lang. Id. Educ. 2017, 16, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Strasbourg Cedex; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Berasategi, N. Ikasle Autoktonoak eta Ikasle Etorkinak Bilboko Eskoletan: Eskola Mota eta Praktika Linguistikoak (Autochthonous and Migrant Students in the Schools of Bilbao: Type of School and Linguistic Practices). Tantak Euskal Herriko Unibertsitateko Hezkuntza Aldizkaria 2016, 28, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Basque Government, J. El Euskera ha Ganado 223.000 Hablantes en los Últimos 25 Años en la Comunidad Autónoma de Euskadi, Navarra e Iparralde (An Increase of 223,000 Basque Speakers in the Last 25 Years in the Basque Autonomous Community, Navarre and Iparralde). Available online: http://www.euskadi.eus/gobierno-vasco/-/noticia/2017/el-euskera-ha-ganado-223-000-hablantes-en-los-ultimos-25-anos-en-la-comunidad-autonoma-de-euskadi-navarra-e-iparralde/ (accessed on 5 July 2019).

- Zabalo, J. Euskal Nazionalismo Motak Nazio Ikuskeraren Arabera (The Impact of Nation Perspectives on Basque Nationalism). Uztaro 1998, 26, 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- MacClancy, J. Expressing Identities in the Basque Arena; Oxford Sar Press: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2007; ISBN 9780852559949. [Google Scholar]

- Egiguren, J.M. El PSOE en el País Vasco (PSOE in the Basque Country); Haranburu Editor: Donostia, Spain, 1984; ISBN 8474072093. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, I. ETA 1958–Medio Siglo de Historia (ETA 1958–Half of a Century of History); Txalaparta: Tafalla, Spain, 2007; ISBN 9788481365078. [Google Scholar]

- Letamendia, F. Juego de Espejos: Conflictos Nacionales Centro-Periferia (Mirror Game: National Conflicts in Center-Periphery); Editorial Trotta: Madrid, Spain, 1997; ISBN 9788481641561. [Google Scholar]

- Berasategi, N. La Diversidad en la Escuela desde la Perspectiva Lingüística y Cultural (School Diversity From Cultural and Linguistic Perspectives). Revista Ciencias Humanas Soc. 2015, 6, 128–144. [Google Scholar]

- Basque Institute of Statistics. Alumnado Matriculado en Enseñanzas de Régimen General no Universitarias en la C.A. de Euskadi de Nacionalidad Extranjera por Titularidad del Centro y Nivel de Enseñanza, Según Territorio Histórico y Modelo Lingüístico. 2017/18 (Migrant Students Enrolled in Compulsory Education in the BAC. Kind of School, Level of Study, Location and Linguistic Model. 2017/18). Available online: http://www.eustat.eus/elementos/ele0013200/Alumnado_matriculado_en_ensenanzas_de_regimen_general_no_universitarias_en_la_CA_de_Euskadi_nacido_en_el_extranjero_por_titularidad_del_centro_y_nivel_de_ensenanza_segun_territorio_historico_y_modelo_linguistico/tbl0013229_c.html (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Urla, J.; Burdick, C. Counting matters: Quantifying the vitality and value of Basque. Int. J. Soc. Lang. 2018, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy 2.0: A.k.a the remix. Harvard Educ. Rev. 2014, 1, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, G.; Idoiaga, N.; Berasategi, N. Inclusion Processes with Refugees and Migrants: Best Practices and Strategies in Leisure and Free Time; Editorial Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; ISBN 978-84-17690-38-0. [Google Scholar]

- Basque Institute of Statistics. El 28% de las Personas Residentes en la C.A. de Euskadi en 2016 Había Nacido Fuera de Ella (28% of the People Living in the BAC in 2016 had Been Born out of the BAC). Available online: http://www.eustat.eus/elementos/El_28_de_las_personas_residentes_en_la_CA_de_Euskadi_en_2016_habia_nacido_fuera_de_ella/not0014789_c.html (accessed on 18 December 2015).

- Statistics Institute of Navarre. Padrón de Habitantes a 1 de enero de Datos Provisionales (Enrollment of Inhabitants Januay 1 Provisional Measure). Available online: https://www.navarra.es/home_es/Gobierno+de+Navarra/Organigrama/Los+departamentos/Economia+y+Hacienda/Organigrama/Estructura+Organica/Instituto+Estadistica/NotasPrensa/Padron+Continuo+de+Habitantes.htm (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Navarre Education. Modelos Lingüísticos (Linguistic Models). Available online: https://www.educacion.navarra.es/web/dpto/modelos-linguisticos (accessed on 7 November 2019).

- Alemany, I.; Ortiz, M.M.; Rojas, G.; Herrera, L. Convivencia Escolar: Percepciones de los Profesores de Primaria y Secundaria de la Ciudad Autónoma de Melilla (School Cohabitation: Primary and Pre-School Teachers Percetions in the Autonomous City of Melilla). Revista Iberoamericana Educ. 2012, 61, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Xhaferi, G.; Xhaferi, B. Teacher’s Perceptions of Multilingual Education and Teaching in a Multilingual Classroom—The Case of the Republic of Macedonia. Jezikoslovje 2012, 13, 2679–2696. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Riaño, X.A.; Armesto-Fernádez, X. Minority Language Teaching and Teacher Satisfaction: The Case of Asturias. Cultura Educ. 2012, 24, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Álvarez, M. ¡Bable nes escueles! Averamientu hestórico-políticu a la vindicación de la enseñanza de la llingua asturiana (‘Bable’ in schools! Historical political approach to the Asturian language’s teaching vindication). Lletres Asturianes 2018, 119, 117–151. [Google Scholar]

- Trenchs-Parera, M.; Newman, M. Diversity of Language Ideologies in Spanish-Speaking Youth of Different Origins in Catalonia. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2009, 30, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.; Patiño-Santos, A.; Trenchs-Parera, M. Linguistic Reception of Latin American Students in Catalonia and their Responses to Educational Language Policies. Int. J. Bilingual Educ. Bilingualism 2013, 16, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, J. Towards Multilingual Education: Basque Educational Research from an International Perpspective; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria, B. Schooling, Language and Ethnic Identity in the Basque Autonomous Community. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 2003, 34, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadez, C.; Etxeberria, F.; Intxausti, N. Language Revitalization and the Normalization of Basque: A Study of Teacher Perceptions and Expectations in the Basque Country. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2015, 16, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejerina, B. El Poder de los Símbolos. Identidad Colectiva y Movimiento Etnolingüístico en el País Vasco. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 1999, 88, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arocena Egaña, E.; Cenoz, J.; Gorter, D. Teachers’ Beliefs in Multilingual Education in the Basque Country and Frieseland. J. Immers. Content Based Lang. Educ. 2015, 3, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubiner, D.; Deeb, I.; Schawartz, M. ‘We are Creating a Reality’: Teacher Agency in Early Bilingual Education. Lang. Cult. Curric. 2018, 31, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó Murchadha, N.; Flynn, C.J. Educators Target Lanaguage Varieties for Language Learners: Orientation toward ‘Navtive’ and ‘Nonnative’ Norms in a Minority Language Context. Mod. Lang. J. 2018, 102, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, S.; Kovacs, C.; Pit-ten Cate, I. Teachers’ Attitudes towards Ethnic Minority Students: Effects of Schools’ Cultural Diversity. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 89, 616–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basque Government. Evaluación de Diagnóstico El Alumnado Inmigrante en Euskadi. Características y Análisis de los Resultados (Diagnosis Assessment Immigrant Studentship in the BAC. Characteristics and Analysis of Results); ISEI-IVEI: Bilbao, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Paciotto, C. What do I Lose if I Lose my Bilingual School? Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions of the Value of a Slovene Language Maintenance Program in Italy. Int. J. Bilingual Educ. Bilingualism 2009, 12, 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, S.; Muller, C. Gatekeepers of the American Dream: How Teachers’ Perceptions Shape the Academic Outcomes of Immigrant and Language Minority Students. Soc. Sci. Res. 2014, 51, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New, W.H. New Language, New World. In Awakened Conscience: Studies in Commonwealth Literature; Narasimhaiah, C.D., Ed.; Heinemann: London, UK, 1978; ISBN 978-0861860104. [Google Scholar]

- Kamau, B. History of the Voice: The Development of Nation Language in Anglophone Caribbean Poetry; New Beacon Books: London, UK, 1984; ISBN 978-0901241559. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffin, H. Post-Colonial Literatures and Counter-Discourse. Kunapipi 1987, 9, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- García, I.; Larrañaga, N.; Berasategi, N.; Azurmendi, M.J. Attitudes Towards Languages, Contact Cultures, and Immigrant Groups According to the Ethnolinguistic Identity of Basque Students. Cult. Educ. 2017, 29, 62–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujolar, J. Immigration and language education in Catalonia: Between national and social agendas. Linguist. Educ. 2010, 21, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).