Teacher Recruitment and Retention: A Critical Review of International Evidence of Most Promising Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Common Approaches Used to Improve Teacher Recruitment and Retention

2.1.1. Financial Incentives (Including Scholarships, Bursaries, Higher Wages)

2.1.2. Alternative Routes into Teaching

2.1.3. Induction Programmes and Mentoring

2.1.4. Professional Development

2.1.5. Leadership Support

2.1.6. Additional Incentives

2.2. Previous Reviews of the Literature

3. Methods

- What are the most promising approaches in attracting teachers into the profession?

- What are the most promising approaches in retaining teachers into the profession?

- What are the ‘best bets’ for schools, regions, and policymakers to improve the recruitment and retention of school teachers?

3.1. Search Strategy

Teacher supply OR teacher demand OR teacher retention OR teacher shortage OR teacher recruitment AND initiative OR incentive* OR policy/scheme AND experiment OR quasi-experiment OR randomised control* trial RCT OR regression discontinuity OR difference in difference OR time series OR longitudinal OR systematic review OR review OR meta-analys* AND impact OR evaluation OR effect.

- Education Resources Information Clearinghouse

- JSTOR

- The Scholarly Journal Archive

- Social Sciences and Education Full Text

- Web of Science

- Sage

- Science Direct

- Proquest Dissertations and Theses

- British Education Index

- ERIC (Educational Resources Information Center)

- IBSS (International Bibliography of the Social Sciences)

- Ingenta Journals (full text of a large number of journals)

- EBSCOhost (which covers the following databases: PsychINFO, BEI, PsycARTICLES, etc, ProQuest, IBSS

- Plus Google and Google Scholar.

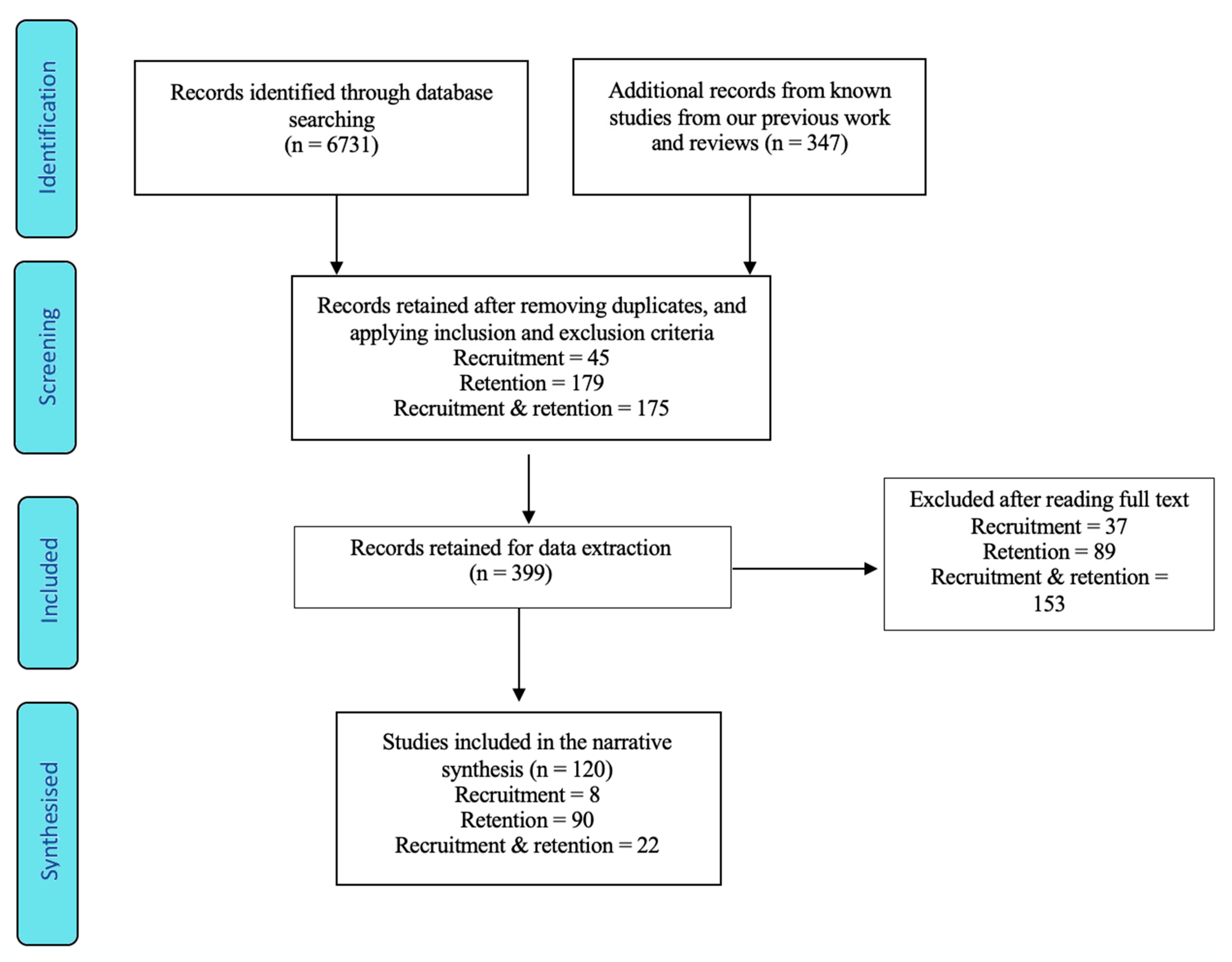

3.2. Screening

3.3. Inclusion Criteria

- Empirical research

- About activities aimed at attracting people into teaching or about retaining teachers in teaching

- Specifically about recruitment and/or retention of classroom teachers

- About incentives/initiatives/policies or schemes on teacher recruitment and retention

- About mainstream teachers in state-funded/government schools

- Studies that had measurable outcomes (either retention or recruitment)

3.4. Exclusion Criteria

- Not relevant to the research questions

- Not primary research

- Not reported in English

- Not a report of research

- Descriptions of programmes or initiatives with no evaluation of strategies or approaches used in teacher recruitment and retention

- Not about strategies or approaches to improve recruitment or retention of teachers (e.g., observational or correlational studies of factors influencing recruitment and retention)

- Studies that had no clear evaluation of outcomes

- Studies with non-tangible or measurable outcomes (e.g., surveys about teachers’ attitude or beliefs or perceptions

- Ethnographic studies, narrative case studies, opinion pieces

- Outcome is not teacher recruitment or retention

- Focus only on specific groups of teachers, e.g., special education teachers or ethnic minority teachers

- Not relevant to the context of English speaking developed countries

- Recruitment and retention of school leaders, teaching assistants or school administrators

- Anecdotal accounts from schools about successful strategies

- Surveys collecting ideas about the best way or most effective ways to attract and retain teachers

3.5. Data Extraction

(the most robust that could be expected in reality). This is an indication of how secure the findings are. We use the term “quality” to refer to the security of the findings and not necessarily the quality of the research. The ratings take no account of whether the intervention was deemed successful or not, or whether the report author claimed the intervention was effective. To ensure inter-rater reliability, four members of the team reviewed and rated a sample of five papers. Team members were in constant consultations with each other throughout the process to ensure consistency.

(the most robust that could be expected in reality). This is an indication of how secure the findings are. We use the term “quality” to refer to the security of the findings and not necessarily the quality of the research. The ratings take no account of whether the intervention was deemed successful or not, or whether the report author claimed the intervention was effective. To ensure inter-rater reliability, four members of the team reviewed and rated a sample of five papers. Team members were in constant consultations with each other throughout the process to ensure consistency.3.6. Synthesising the Evidence

and above) showing negative or no effects are considered least promising given the existing evidence. All outcomes, whether positive or negative are considered. It is just as important to identify approaches that do not have evidence of effectiveness as it is to identify those that do work. It has to be made clear that approaches with no evidence of impact does not mean that they are not effective, but rather that the existing evidence is such that its effectiveness cannot be determined.

and above) showing negative or no effects are considered least promising given the existing evidence. All outcomes, whether positive or negative are considered. It is just as important to identify approaches that do not have evidence of effectiveness as it is to identify those that do work. It has to be made clear that approaches with no evidence of impact does not mean that they are not effective, but rather that the existing evidence is such that its effectiveness cannot be determined.4. Results

or 1

or 1 rating are not discussed in any further detail as their limited design or methodological quality means that they offer little in terms of indicating promising (or otherwise) approaches. Appendix C summarises the weaker studies (rated 0

rating are not discussed in any further detail as their limited design or methodological quality means that they offer little in terms of indicating promising (or otherwise) approaches. Appendix C summarises the weaker studies (rated 0 and 1

and 1 ). These are mainly studies with very weak design. They either had very small samples, non-randomly allocated comparison groups, had no clear comparators, high attrition or based on models that made a number of unrealistic assumptions. All this makes it difficult to attribute the effect to the policy initiative or intervention. Therefore, including them in the discussion will add little to the overall finding.

). These are mainly studies with very weak design. They either had very small samples, non-randomly allocated comparison groups, had no clear comparators, high attrition or based on models that made a number of unrealistic assumptions. All this makes it difficult to attribute the effect to the policy initiative or intervention. Therefore, including them in the discussion will add little to the overall finding.4.1. Approaches to Attracting Teachers

and above (Table 2). All but two involve some kind of financial incentives (Table 3). This is perhaps because large-scale administrative/panel data relating to financial incentives are more readily available and accessible, and efficient to examine for researchers.

and above (Table 2). All but two involve some kind of financial incentives (Table 3). This is perhaps because large-scale administrative/panel data relating to financial incentives are more readily available and accessible, and efficient to examine for researchers.4.1.1. Financial Incentives

) shows mixed outcomes, but otherwise the results from the 2

) shows mixed outcomes, but otherwise the results from the 2 studies are predominantly positive (Table 3). This suggests that there is promising, but far from definitive evidence that financial incentives may be an effective strategy in attracting teachers into the profession and to specific regions, subjects or hard-to-staff schools.

studies are predominantly positive (Table 3). This suggests that there is promising, but far from definitive evidence that financial incentives may be an effective strategy in attracting teachers into the profession and to specific regions, subjects or hard-to-staff schools. on recruitment [84] evaluated the impact of financial incentives on recruitment and retention of shortage subject teachers. The results were mixed. The study utilised an instrumental variables model using data from the School and Staffing Survey from 1999/2000 to 2007/2008 which contained data from 106,930 public school teachers in 6540 public school districts. This is perhaps the largest study of its kind and several models were employed within it. One compared teachers in districts that offered incentives with matched teachers in other districts. This does not overcome the problem that districts that did and did not offer such incentives may have other differences that could influence teacher recruitment and retention. There was no clear evidence that the use of incentives improved teacher recruitment or quality. Incentives were most attractive to those who were already interested in becoming teachers.

on recruitment [84] evaluated the impact of financial incentives on recruitment and retention of shortage subject teachers. The results were mixed. The study utilised an instrumental variables model using data from the School and Staffing Survey from 1999/2000 to 2007/2008 which contained data from 106,930 public school teachers in 6540 public school districts. This is perhaps the largest study of its kind and several models were employed within it. One compared teachers in districts that offered incentives with matched teachers in other districts. This does not overcome the problem that districts that did and did not offer such incentives may have other differences that could influence teacher recruitment and retention. There was no clear evidence that the use of incentives improved teacher recruitment or quality. Incentives were most attractive to those who were already interested in becoming teachers. showing positive effects. These were not rated higher because of some limitations in the research design. These studies suggest that financial incentives, such as higher wages, stipends and bonuses can entice teachers to teach in challenging schools. DeFeo et al. [85] estimated that higher salaries are needed to attract more qualified teachers to teach in hard-to-staff schools. They analysed data from twelve Alaskan school communities in three districts to determine the minimum salary needed to attract highly qualified teachers in rural communities in Alaska, and how much more is needed to get teachers to teach in difficult-to-staff schools. Their analysis suggests that to compensate for factors that might make a community or school more or less attractive, salary differential would have to be between 0.85 and 2.01 with hard-to-staff schools having higher differentials. The differentials include costs of living among other working and living conditions that affect teachers staying or leaving communities. So, it might be the case that to attract maths and science graduates (who would command higher salaries elsewhere), the salary differential would have to be big enough to compensate for the difference they would otherwise get. It has to be mentioned that the amount of the bonus would have to be the salary differences on the teacher’s actual salary and not the state salary schedule as some districts were already paying teachers more than was stipulated in the state salary schedule. Otherwise even with compensatory bonus, teachers’ salaries could be the same or even below what they were already getting.

showing positive effects. These were not rated higher because of some limitations in the research design. These studies suggest that financial incentives, such as higher wages, stipends and bonuses can entice teachers to teach in challenging schools. DeFeo et al. [85] estimated that higher salaries are needed to attract more qualified teachers to teach in hard-to-staff schools. They analysed data from twelve Alaskan school communities in three districts to determine the minimum salary needed to attract highly qualified teachers in rural communities in Alaska, and how much more is needed to get teachers to teach in difficult-to-staff schools. Their analysis suggests that to compensate for factors that might make a community or school more or less attractive, salary differential would have to be between 0.85 and 2.01 with hard-to-staff schools having higher differentials. The differentials include costs of living among other working and living conditions that affect teachers staying or leaving communities. So, it might be the case that to attract maths and science graduates (who would command higher salaries elsewhere), the salary differential would have to be big enough to compensate for the difference they would otherwise get. It has to be mentioned that the amount of the bonus would have to be the salary differences on the teacher’s actual salary and not the state salary schedule as some districts were already paying teachers more than was stipulated in the state salary schedule. Otherwise even with compensatory bonus, teachers’ salaries could be the same or even below what they were already getting. study showed mixed outcome—successful for some schools only. Fulbeck and Richards [93] explored the effects of ProComp, a performance-based financial incentive, on teacher mobility in Denver, CO, USA. Teachers were awarded an additional $24,000 if they taught in top performing schools, high growth schools or hard-to-staff schools. Seven such incentives were given to individual teachers for meeting student performance targets, and three were school-based incentives awarded to teachers who taught at hard-to-staff schools serving low-income population, high performing schools and schools that make the most progress in maths and reading. However, ProComp was eligible only to those who were members of teacher unions and who did not work in Charter schools. The sample included all public school teachers in Denver from 2006–2010 who were eligible for the incentive (regardless of whether they received it) and who made at least one voluntary move within the district (n = 989). Using conditional logit models, the authors predicted which school a teacher would transfer to given their individual characteristics, the characteristics of their current school, and the characteristics of the schools they could be transferring to. The results portrayed the incentive as successful in attracting teachers to high growth and high performing schools, but less successful in getting teachers into schools with a high proportion of low-income pupils or hard-to-staff schools. Financial incentives also did not encourage teachers to move out of the area they were currently in.

study showed mixed outcome—successful for some schools only. Fulbeck and Richards [93] explored the effects of ProComp, a performance-based financial incentive, on teacher mobility in Denver, CO, USA. Teachers were awarded an additional $24,000 if they taught in top performing schools, high growth schools or hard-to-staff schools. Seven such incentives were given to individual teachers for meeting student performance targets, and three were school-based incentives awarded to teachers who taught at hard-to-staff schools serving low-income population, high performing schools and schools that make the most progress in maths and reading. However, ProComp was eligible only to those who were members of teacher unions and who did not work in Charter schools. The sample included all public school teachers in Denver from 2006–2010 who were eligible for the incentive (regardless of whether they received it) and who made at least one voluntary move within the district (n = 989). Using conditional logit models, the authors predicted which school a teacher would transfer to given their individual characteristics, the characteristics of their current school, and the characteristics of the schools they could be transferring to. The results portrayed the incentive as successful in attracting teachers to high growth and high performing schools, but less successful in getting teachers into schools with a high proportion of low-income pupils or hard-to-staff schools. Financial incentives also did not encourage teachers to move out of the area they were currently in. studies found no impact of financial incentives on teacher recruitment. Bueno and Sass [94] assessed the impact of the Georgia’s bonus system (a monetary compensation) on the recruitment and retention of maths and science teachers. The bonus system increased the pay of new maths and science teachers to make it equal to that of a teacher with six years of experience. A difference-in-difference model was used to estimate the impact of the differential pay programme on the likelihood of becoming a teacher by comparing the difference between graduates with majors in maths and science and other education majors in the change before and after the programme period. They found that differential pay did not increase the number of maths or science teachers nor did it encourage people to switch to maths or science.

studies found no impact of financial incentives on teacher recruitment. Bueno and Sass [94] assessed the impact of the Georgia’s bonus system (a monetary compensation) on the recruitment and retention of maths and science teachers. The bonus system increased the pay of new maths and science teachers to make it equal to that of a teacher with six years of experience. A difference-in-difference model was used to estimate the impact of the differential pay programme on the likelihood of becoming a teacher by comparing the difference between graduates with majors in maths and science and other education majors in the change before and after the programme period. They found that differential pay did not increase the number of maths or science teachers nor did it encourage people to switch to maths or science.4.1.2. Alternative Routes into Teaching

, and so is discussed here.

, and so is discussed here.4.1.3. Teacher Accountability

4.2. Approaches to Retaining Teachers

studies and the eight studies with a 3

studies and the eight studies with a 3 rating, all had unclear, neutral or negative outcomes. The majority of studies in this section either focus on financial incentive interventions or those which provide professional development and/or mentoring. Several of those relating to financial incentives have already been described above under recruitment, and so are referred to only briefly below.

rating, all had unclear, neutral or negative outcomes. The majority of studies in this section either focus on financial incentive interventions or those which provide professional development and/or mentoring. Several of those relating to financial incentives have already been described above under recruitment, and so are referred to only briefly below.4.2.1. Financial Incentives

) do not suggest clear benefits (Table 7).

) do not suggest clear benefits (Table 7). , looked at whether actual receipt and the amount of performance pay award in an urban school district as opposed to eligibility made a difference to teachers’ decision to leave or stay. Using the difference between a large and a small award as the cut-off threshold, they conducted a regression discontinuity analysis using census data for 12,000 teachers although they focused only on 3363 teachers. Teachers in the top quartile of value-added scores were rewarded with a large award and teachers with a value-added score in the second quartile a small award. Their analysis showed that likelihood of retention was slightly higher for teachers who received a small award rather than no award. However, this study found that teachers who received a large award were less likely than teachers who received a small award to be retained in the district. Perhaps teachers in receipt of a large award are high performing teachers who can easily find better paid jobs elsewhere.

, looked at whether actual receipt and the amount of performance pay award in an urban school district as opposed to eligibility made a difference to teachers’ decision to leave or stay. Using the difference between a large and a small award as the cut-off threshold, they conducted a regression discontinuity analysis using census data for 12,000 teachers although they focused only on 3363 teachers. Teachers in the top quartile of value-added scores were rewarded with a large award and teachers with a value-added score in the second quartile a small award. Their analysis showed that likelihood of retention was slightly higher for teachers who received a small award rather than no award. However, this study found that teachers who received a large award were less likely than teachers who received a small award to be retained in the district. Perhaps teachers in receipt of a large award are high performing teachers who can easily find better paid jobs elsewhere. ) found no effect of financial incentives on teacher retention. Steele et al. [89] evaluated the Governor’s Teaching Fellowship (GTF) scheme, involving a $20,000 incentive to attract new teachers to low-performing schools. Teachers had to repay $5000 for each of the first four year that they did not meet the commitment. There was no difference in retention rates (75% over four years) between recipient and non-recipients, despite the penalty clause.

) found no effect of financial incentives on teacher retention. Steele et al. [89] evaluated the Governor’s Teaching Fellowship (GTF) scheme, involving a $20,000 incentive to attract new teachers to low-performing schools. Teachers had to repay $5000 for each of the first four year that they did not meet the commitment. There was no difference in retention rates (75% over four years) between recipient and non-recipients, despite the penalty clause. reported positive outcomes of financial incentives on teacher retention, but the effects were either short-lived or involved some kind of a tie-in. Bueno and Sass [95] found that salary compensation only had a short-term effect on the retention of teachers. They compared teachers who were eligible with those who were not. The attrition rate for bonus recipients was lower than non-recipients, but only in the first five years when they were receiving the bonus. Working and living conditions, lack of community engagements were reported to be important factors in teachers’ decision to stay or leave.

reported positive outcomes of financial incentives on teacher retention, but the effects were either short-lived or involved some kind of a tie-in. Bueno and Sass [95] found that salary compensation only had a short-term effect on the retention of teachers. They compared teachers who were eligible with those who were not. The attrition rate for bonus recipients was lower than non-recipients, but only in the first five years when they were receiving the bonus. Working and living conditions, lack of community engagements were reported to be important factors in teachers’ decision to stay or leave. studies showed unclear or mixed outcomes. Booker and Glazerman [110] evaluated the Missouri Career Ladder (CL) Program to test the effect of pay increases on teachers at different stages of their career. Based on their performance-level eligible teachers received supplementary pay for taking on certain responsibilities or professional development outside their contracted hours. Teachers were observed and evaluated as they moved up the career ladder in three stages. The amount of bonus was also related to the length of teaching experience. For each stage teachers received more supplementary pay up to £1500 for Stage 1, £3000 for Stage 2 and £5000 for Stage 3. The authors compared the retention rates of teachers in districts offering the Career Ladder incentive with similar teachers in non-Career Ladder districts. There was no difference in retention rates between CL and non-CL districts after controlling for observable differences such as wealth, size and population density in regression models. Using instrumental variables controlling for district selection into CL participation, teachers in CL districts were less likely to move to a different district. The model predicted that after 10 years teachers in CL districts were less likely to move compared to similar teachers in non-CL districts (81% remain vs 77%). The oldest teachers (after 11 years and receiving the biggest bonuses) were half as likely to move compared to their non-CL peers. It was more effective in retaining younger teachers in the profession but not necessarily in the district. The authors estimated that incentive payments need to exceed 25% of teacher salary to neutralise the effects of turnover in hard-to-staff urban schools. One complication is that this programme also had an element of enhancing teacher autonomy. Therefore, it is not clear how much of the effect was due to the incentive and how much was the result of teachers’ enhanced autonomy.

studies showed unclear or mixed outcomes. Booker and Glazerman [110] evaluated the Missouri Career Ladder (CL) Program to test the effect of pay increases on teachers at different stages of their career. Based on their performance-level eligible teachers received supplementary pay for taking on certain responsibilities or professional development outside their contracted hours. Teachers were observed and evaluated as they moved up the career ladder in three stages. The amount of bonus was also related to the length of teaching experience. For each stage teachers received more supplementary pay up to £1500 for Stage 1, £3000 for Stage 2 and £5000 for Stage 3. The authors compared the retention rates of teachers in districts offering the Career Ladder incentive with similar teachers in non-Career Ladder districts. There was no difference in retention rates between CL and non-CL districts after controlling for observable differences such as wealth, size and population density in regression models. Using instrumental variables controlling for district selection into CL participation, teachers in CL districts were less likely to move to a different district. The model predicted that after 10 years teachers in CL districts were less likely to move compared to similar teachers in non-CL districts (81% remain vs 77%). The oldest teachers (after 11 years and receiving the biggest bonuses) were half as likely to move compared to their non-CL peers. It was more effective in retaining younger teachers in the profession but not necessarily in the district. The authors estimated that incentive payments need to exceed 25% of teacher salary to neutralise the effects of turnover in hard-to-staff urban schools. One complication is that this programme also had an element of enhancing teacher autonomy. Therefore, it is not clear how much of the effect was due to the incentive and how much was the result of teachers’ enhanced autonomy. indicated that financial incentives did not improve retention of teachers. A study in England looked at whether pay reforms in England where schools are given the freedom to set pay based on performance rather than seniority have impacted on teacher retention. Anders et al. [43] compared three groups of schools—the positive adopters where pay progression on average was faster than pre-reform seniority-based salary schedule; negative adopters where pay progression was slower than expected under pre-reform; and mean-zero adopters where pay progression was as expected under pre-reform pay schedule based on seniority. Using a difference-in-difference framework the authors estimated the effect of pay reforms on teacher retention, using adopters as treatment groups. The effect of the reform increased teachers’ pay at positive adopter schools by 4% while pay of teachers in negative adopter schools fell by 3%. However, there were no effects on retention.

indicated that financial incentives did not improve retention of teachers. A study in England looked at whether pay reforms in England where schools are given the freedom to set pay based on performance rather than seniority have impacted on teacher retention. Anders et al. [43] compared three groups of schools—the positive adopters where pay progression on average was faster than pre-reform seniority-based salary schedule; negative adopters where pay progression was slower than expected under pre-reform; and mean-zero adopters where pay progression was as expected under pre-reform pay schedule based on seniority. Using a difference-in-difference framework the authors estimated the effect of pay reforms on teacher retention, using adopters as treatment groups. The effect of the reform increased teachers’ pay at positive adopter schools by 4% while pay of teachers in negative adopter schools fell by 3%. However, there were no effects on retention.4.2.2. Teacher Development and Support

suggested positive effects, the two strongest studies rated 3

suggested positive effects, the two strongest studies rated 3 , using randomized control designs, showed that mentoring and induction did not make a difference to teacher retention.

, using randomized control designs, showed that mentoring and induction did not make a difference to teacher retention. studies mostly reported positive outcomes. Allen and Sims [57] evaluated STEM Learning Network professional development courses intended to improve teachers’ subject, pedagogical and career knowledge, confidence and motivation. They used retention data of teachers from England’s Department for Education (DfE) School Workforce Census. This was matched with the National STEM Learning Network to identify teachers who participated in the CPD courses. The authors used propensity score matching, matching participants with non-participants by known characteristics. To control for unobserved differences, comparisons were made between those who participated in 2010 with those who participated later. The authors argued that these individuals were therefore more likely to be similar in terms of motivation and career plans. Further analyses were also made comparing science departments in schools before and after the treatment. The study suggests that taking part in National STEM Learning Network professional development is associated with an increase in retention in the profession as a whole. The odds that a participant stays in the profession one year after completing these courses was around 160% higher than for similar non-participants, and the positive association is sustained two years later for recently qualified teachers. Using the more rigorous double-difference and triple-difference models that takes into account factors that are not included in the demographic and background measures, the positive association is maintained. However, there is no evidence that completing CPD courses improves retention within the schools that teachers were working in at the time of participation.

studies mostly reported positive outcomes. Allen and Sims [57] evaluated STEM Learning Network professional development courses intended to improve teachers’ subject, pedagogical and career knowledge, confidence and motivation. They used retention data of teachers from England’s Department for Education (DfE) School Workforce Census. This was matched with the National STEM Learning Network to identify teachers who participated in the CPD courses. The authors used propensity score matching, matching participants with non-participants by known characteristics. To control for unobserved differences, comparisons were made between those who participated in 2010 with those who participated later. The authors argued that these individuals were therefore more likely to be similar in terms of motivation and career plans. Further analyses were also made comparing science departments in schools before and after the treatment. The study suggests that taking part in National STEM Learning Network professional development is associated with an increase in retention in the profession as a whole. The odds that a participant stays in the profession one year after completing these courses was around 160% higher than for similar non-participants, and the positive association is sustained two years later for recently qualified teachers. Using the more rigorous double-difference and triple-difference models that takes into account factors that are not included in the demographic and background measures, the positive association is maintained. However, there is no evidence that completing CPD courses improves retention within the schools that teachers were working in at the time of participation. showed mixed outcome. Weisbender [125] evaluated the California Mentor Teacher Program which was developed to retain experienced teachers and to assist new teachers in the transition into teaching. Under this scheme, highly talented classroom teachers (mentors) were given the incentive to continue teaching and to use their instructional expertise to mentor their peers and new teachers (mentees). The study included 336 mentors and 638 of their mentees in 240 schools and 46 retirees in the Priority Staffing Program serving 46 schools. Personnel records and questionnaires over a 5-year period were collected to assess the length of time each cohort stayed in the district. Comparisons were made between mentors and a matched group of non-mentors. Results varied from cohort to cohort. There was no effect on retention for the first cohort, with non-mentees being more likely to stay within the school district compared to mentees. With the subsequent cohorts, mentees were more likely to stay compared to non-mentees. On the other hand, mentors were also more likely to leave over the 5-year period than non-mentors. Although comparison mentors were matched, the selection of highly effective teachers suggest that the two groups may not be equal. As Shifrer et al. [98] noted, it may be the case the high performing teachers can find jobs more easily and are therefore more mobile.

showed mixed outcome. Weisbender [125] evaluated the California Mentor Teacher Program which was developed to retain experienced teachers and to assist new teachers in the transition into teaching. Under this scheme, highly talented classroom teachers (mentors) were given the incentive to continue teaching and to use their instructional expertise to mentor their peers and new teachers (mentees). The study included 336 mentors and 638 of their mentees in 240 schools and 46 retirees in the Priority Staffing Program serving 46 schools. Personnel records and questionnaires over a 5-year period were collected to assess the length of time each cohort stayed in the district. Comparisons were made between mentors and a matched group of non-mentors. Results varied from cohort to cohort. There was no effect on retention for the first cohort, with non-mentees being more likely to stay within the school district compared to mentees. With the subsequent cohorts, mentees were more likely to stay compared to non-mentees. On the other hand, mentors were also more likely to leave over the 5-year period than non-mentors. Although comparison mentors were matched, the selection of highly effective teachers suggest that the two groups may not be equal. As Shifrer et al. [98] noted, it may be the case the high performing teachers can find jobs more easily and are therefore more mobile.4.2.3. Alternative Routes to Teaching

that examined alternative routes into teaching showed no clear advantages of any alternative pathways in retaining teachers (Table 9).

that examined alternative routes into teaching showed no clear advantages of any alternative pathways in retaining teachers (Table 9).4.2.4. Teacher Accountability

5. Discussion

5.1. The Evidence on Recruitment and Retention to the Teaching Profession

5.2. Beyond Financial Incentives—Implications for Policy, Practice and Research

5.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Review

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Overview

Brief Description of the Intervention

- -

- Aim and type of intervention: e.g., financial incentives (performance-related pay, scholarships, bursaries, housing benefits, pension scheme)

- -

- Phase: Primary/secondary/general

- -

- Country:

- -

- How the intervention works: There must be enough information to enable identification of key features of a successful intervention, if it works.

Method

Research Design

- -

- Does it have a control and comparison group?

- -

- Does it have pre- and post- event comparison?

- -

- How is randomisation or other allocation to groups carried out?

- -

- Was there an intervention?

Sample

- -

- Size of sample

- -

- How were samples identified?

- -

- School characteristics, e.g., primary, secondary, rural, urban, challenging schools

- -

- How many cases were lost at each stage?

Outcome Measures

- -

- Is there a pre-defined primary outcome, or is there an element of ‘dredging’ for success?

Analysis (if Relevant)

- -

- What kind of analysis was carried out?

- -

- Are there pre- and post-test comparisons?

- -

- Are effect sizes cited or calculable?

- -

- How was the performance of treatment and comparison groups compared?

Findings

- -

- Reviewers’ analysis of the results (re-calculate effect sizes if not estimated or if in doubt).

Commentary

Appendix B

| Design | Scale | Dropout | Outcomes | Other Threats | Rating |

| Fair design for comparison (e.g., RCT) | Large number of cases per comparison group | Minimal attrition, no evidence of impact on findings | Standardised pre-specified independent outcome | No evidence of diffusion or other threat | 4 |

| Balanced comparison (e.g., RDD, Difference-in-Difference) | Medium number of cases per comparison group | Some initial imbalance or attrition | Pre-specified outcome, not standardised or not independent | Indication of diffusion or other threat, unintended variation in delivery | 3 |

| Matched comparison (e.g., Propensity score matching) | Small number of cases per comparison group | Initial imbalance or moderate attrition | Not pre-specified but valid outcome | Evidence of experimenter effect, diffusion or variation in delivery | 2 |

| Comparison with poor or no equivalence (e.g., volunteers) | Very small number of cases per comparison group | Substantial imbalance and/or high attrition | Outcome with issues of validity or appropriateness | Strong indication of diffusion or poorly specified approach | 1 |

| No report of comparator | A trivial scale of study, or N unclear | Attrition not reported or too high for any comparison | Too many outcomes, weak measures, or poor reliability | No consideration of threats to validity | 0 |

Appendix C

| Study | Strategy | Impact | Evidence |

| Adnot et al. 2017 | Performance incentive (financial incentives) | Positive effect in keeping high-performing teachers in high-poverty schools but not in low-poverty schools | The analysis did not compare teacher retention rates before and after IMPACT nor did it evaluate whether IMPACT improve retention of teachers in general. The study was unable to identify high-performing teachers who leave DCPS because of IMPACT, the estimates indicated that replacing high-performing teachers who exit with teachers who perform similarly is difficult. Also leavers include both voluntary and involuntary leavers. |

| Afolabi 2013 | Professional development (Cross Career Learning Communities) | Positive effect Fewer treatment teachers left teaching or moved from their school than control teachers | QED Groups were matched on individual and school characteristics Teachers participating in CCLC were already in schools with a culture of professional development (groups are not equivalent) The study period also coincided with economic recession which may explain the high retention and lower mobility |

| Barnett and Hudgens 2014 | TAP (Teacher and Student Advancement Programme) | Small positive effect (ES = 0.05) | TAP schools are self-selected. These schools are likely to be different to the national average. Schools that stopped TAP were not included in the analysis. These maybe schools where the programme had not worked. In other words, only successful schools were considered in the analysis. |

| Beattie 2013 | Mentoring | No difference between groups but teachers receiving support from full-release mentors reported more positive experience | Small sample (87) Some teachers were selected to receive full-release mentors and some to school-based mentors Evidence based on teachers’ report of intention rather than actual attrition |

| Bemis 1999 | Mentoring | There is no clear impact of mentoring on retention despite the author’s claim that mentoring programs were found to be most influential on new teacher retention for elementary level teachers. | Small sample Retention based on teachers’ self-report High attrition, therefore, those who did not respond may be different to those who did. The results are therefore not reliable. Districts with mentoring may be different to disctricts with no mentoring. Different attrition rate may be a reflection of differences in the districts. |

| Bobronnikov et al., 2013 | Incentive grant | + Increase in number going into teaching, 80% teaching in high need areas (but no comparator). Not enough data to calculate ES Unclear retention Majority indicated they’d stay on. But of the 6 states, 2 states showed negative impact (no comparison groups) | The study design was unable to test whether recipients of the Noyce programme would have gained teacher certification in STEM subjects and go on to teach in high needs areas in the absence of the programme |

| Bond (2001) | Salary | + States where salary was markedly lower than similarly-education professionals, there was higher teacher turnover and reverse is true (after controlling for family background) | It is a correlational analysis and the states being compared are not the same, there are confounding factors that are not accounted for. |

| Bowman 2007 | Mentoring | Negative impact on retention Experimental teachers were more aware of the career commitment which negatively affect their withdrawal intention. | Small sample (n = 30) Comparison groups were not equivalent. Control teachers had more teaching experience than experimental teachers. No actual data on retention was collected |

| Brown &Wynn 2009 | Role of principal | Positive effect of principal awareness of issues affecting teachers on retention | Not an impact evaluation |

| Cheng and Brown 1992 | Peer support/mentoring | Mixed results

| Evidence was based on teachers’ self-report. The sample was small and imbalance. The 2 groups were not equivalent. Comparison teachers were those that were not eligible for the programme. In the second year, comparison teachers were randomly selected to be in the experimental group. Experimental teachers were also designed to include those that did not have prior experience. |

| Chou 2015 | Mentoring (full-time release for mentors with financial rewards) | Negative result of full-time release mentoring | The 2 school districts being compared are different and the sample size of only 23 is too small to make any sensible judgements on effectiveness. |

| Clamp 2011 | Mentoring | No effect | Comparison groups were self-selected, coupled with the high attrition rates and the self-report survey, the evidence is weak. |

| Clewell and Villegas 2001 | Alternative certification | Impact on recruitment unclear (more pathways graduates completed (75% vs 60%) and ended up teaching in HTSS (84% no comparison) than traditionally certified teachers + on retention ES = 0.1 | Comparisons were made with national average and traditionally certified teachers. The 2 groups of people are therefore likely to be different. Paraprofessionals and emergency-certified teachers, for example, were already working in the schools. It is therefore, hardly surprising that they were more likely to stay in the school or district where they were trained. There was also no comparison of before and after data. |

| Colson and Satterfield 2018 | Financial incentive (The Innovation Acceleration Fund grant, a compensation scheme) | + impact on retention 80% of teachers on the scheme were retained compared to 70% not on the scheme (ES = 0.07) | The very small non-random sample, and exclusion of teachers who did not have TVAAS results meant that the sample might be biased. Comparisons were made with volunteers and non-volunteers |

| Counts 2012 | Induction | Positive effect Administrative support and workload were the strongest predictor of teachers’ commitment to stay in the school (R2 = 0.19 for both). | Calculation of means was used for categorical variables (e.g., strongly agree to strongly disagree). Only 22% of teachers responded to the survey. The views of the majority 78% of new teachers were not captured. |

| Cowman 2004 | Alternative certification | Unclear results But looks like mentoring did not influence retention All programs had relatively high rates of retention; ACP had the highest retention (96.81%), followed by ECP (90%) and then CPDT (89.9%). CPDT teachers reported receiving the most support as they were paired with experienced teachers during the internship, they have the highest attrition. This suggests that factors other than mentoring and support could determine teachers’ decision to leave. ACP had the highest retention rates likely because of their selective process. | Record of attrition may not be accurate. Teachers who are still teaching but have left the state of Texas are treated as teachers who have left the profession because their employment histories are no longer trackable. Those who left temporarily (e.g., maternity) sare treated as having left teaching. |

| Croffut 2015 | Mentoring and Induction | No effect Turnover rate of beginning teachers in the district decreased by 1 percentage point between 2012–2014 and 2014–2015. Comparing teachers’ self-report intention to stay or not, showed no difference between expected and actual response rate. In fact, actual response rate was 88% compared to the expected rate of 90%. | High level of missing data (only 29% responded to survey). Therefore responses could be from self-selected individuals. Evidence of bias in reporting Despite the data showing no effect, the author concluded “While there is no statistically significant difference, the data reveal the district is maintaining the beginning teacher turnover rate which would indicate the district’s beginning teacher program is positively impacting the teacher retention rate” |

| Dwinal 2012 | Alternative certification (Teach For America) | No effect | Based on interviews with superintendents and principals with low response rates (under 20%). Poor reporting. Based on vacancies not placements. |

| Eberhard, Reinhardt-Mondragon and Stottlemyer 2000 | Mentoring and Alternative Certification | + effect of mentoring (compared to no mentoring) + effect of alternative certification (compared to standard certification) Negative effect of emergency certification compared to fully certified teachers | The groups were no randomly selected and as the authors reported, this may be reflective of the kind of pre-service students who would sign up for the more intensive one-year programme. No actual retention data presented. |

| Elmore 2003 | Mentoring | No difference in retention rates although retention of teachers using MTC continued to increase over 2 years while those using peer mentors continued to decrease | No pure control Comparison was with Peer Mentors and Mentor Teacher Consultants Schools were selected for MTC based on high turnover rates and low performance. Schools are therefore different |

| Fleener 1998 | Alternative certification | Positive effect for field-based training (2.1% attrition) compared to university-based training (6.7%) | The 2 groups are self-selected so may be different in terms of motivation and commitment. Also a large number who did not end up in state-funded teaching were excluded. This may have already excluded those who would be likely to leave teaching anyway |

| Fowler 2003 | Massachussets Signing Bonus |

| There was no comparison group. It was simply an analysis of the data on bonus recipients and their outcomes. |

| Fuller (2003) | Mentoring | + effect on retention Although differences in retention rates of participants and non-participants are “significant” effect sizes calculated by reviewer are small (around 0.05 for all the 3 years) | Participants were self-selected or “qualified” for inclusion. Therefore groups being compared were different. The programme had a lot of components, so it was difficult to isolate the effects of mentoring In some all beginning teachers had a mentor, in others there were few or no mentoring for new teachers |

| Gaikhorst et al., 2015 | Professional development for beginning teachers | No effect on retention | Evidence based on teachers’ report of their intention to stay. Experimental teachers were those who volunteered to take part. These were compared with those who did not take part |

| Gold 1987 | Mentoring (New York City retired teachers-as-mentors programme) | Lowers attrition rates among mentored teachers compared to non-mentored, but tiny numbers | This was a small-scale RCT. Although principals were asked to assign mentors at random, it was not clear how this was done. In some cases teachers rejected the offer of a mentor. Assignment was therefore no longer random |

| Goldhaber, Destler and Player 2010 | Financial incentives | + effect Additional $5790 needed for a 50% increase in number of teachers teaching in schools with high proportion of minority children, but only $706 extra for a 50% increase in number of teachers teaching in high poverty schools | Not focused on recruitment and retention specifically |

| Gordon and Vegas 2004 | FUNDEF (Financial incentives) | Increase in number of teachers in poorer regions but no effect on proportion of secondary teachers with higher degrees | Not relevant to English context (funding reform in Brazil). The analyses are correlational and did not take into account other confounding factors |

| Hancock 2008 | External support, mentoring and induction and financial incentives | Mentoring and induction did not predict likelihood of attrition Parent and administrative support reduced the risk of attrition Salary is also significant. For every I unit increase in salary bracket (c. $10,000), there is a 38% reduction in risk (OR = 0.62). | The evidence is based on a large sample of participants based on administrative data. But because the evidence is based on self-report of intention to stay or leave, the evidence is not strong |

| Hansen et al., 2016 | Alternative certification (Teach for America) | Effects are mixed. Clustering has a positive effect on retention of teachers in schools in the district. The higher the density of TFA corps members in a school increases, they are less likely to move schools within district However, it has a negative effect on retention of teachers within district. A 1 percentage point increase in TFA density in the school is associated with a 1.5% greater likelihood of exiting the district | This study can only establish correlation but not causality. It also cannot determine the direction of causation. It is possible that schools with high out-of-district exits are more likely to rely on TFA staffing. |

| Hardie 2008 [full paper not available) | Alternative preparation | No effect on retention | The two groups of teachers were not randomly allocated and no controls were made of teacher background characteristics |

| Harrell and Harris 2006 | Alternative certification (Online post-baccalaureate teacher certification programme) | + effect on recruiting males (ES = 0.2) and minority candidates (ES = 0.19) + effect on recruiting maths and science teachers (ES = 0.2) + effect on recruiting career changers (no comparison for ES calculation) | Because of self-selection into programmes candidates who signed up for traditional programmes are likely to be different to those who signed up for the online programme. The groups are therefore not balanced. Also comparison is made for only one year, it is not possible to rule out other exogenous factors (e.g., economic performance) which may have affected a larger number of people who change career Data was taken from one faculty in one institution and for one academic year only. Sample may not be generalised to other years and institutions. Hence the 1  rating. rating. |

| Harris-McIntyre 2014 | Induction | No clear effect No evidence that alternative (on-the-job training as in Teach First in England) has been effective in retaining teachers in the district. However, non lateral teachers were over twice more likely to stay in teaching in the first and second year, but no difference in the 3rd year | The teachers were neither randomised nor matched by background characteristics. There are likely to be unobservable differences which have not been controlled for in the analysis. |

| Henke, Chen and Geis 2000 | Induction | + effect on retention (15% left compared to 26% not on induction programme, ES = 0.27) | Used data from the Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Survey (n = 7294) It is not clear how many missing cases there were that had not been accounted for. Also the two groups may be different as teachers participating in induction programmes may be in more supportive schools with better working conditions etc. So it is not possible to attribute the lower attrition rate simply to induction alone.

|

| Henry, Bastian and Adrienne 2012 | Financial Merit-based scholarships | + recruitment of high quality graduates (SAT scores of high school scholars 113 points higher than traditionally prepared teachers and GPA scores are 0.6 points higher non-teaching fellows; ranked among the top 10% of graduates) + retention (scholarship recipients more than 1.1 times more likely to stay on for 5 years than other in-state prepared teachers) | Comparisons were not made with similar teachers Scholarship recipients were high-flying graduates who applied and were therefore self-selected. Unobserved confounders such as scholars’ motivations and intentions could not be controlled for. |

| Hopkins 1997 | Induction | No effect on retention (Effect size = 0.03) | Groups not equivalent Missing cases and non-response meant that the groups were no longer balanced Retention based on reported intention |

| Humphrey et al., 2018 | Behaviour management as CPD | No impact on teacher retention (ES = −0.01) | A lot of missing data Low compliance No actual retention data (based on teachers’ expression of intention) |

| Ingersoll, Merrill and May 2014 | Teacher preparation | Positive effect Those that have more pedagogy in their training were less likely to leave Training in teaching strategies and methods made no difference | The study could not control for unobserved differences. Those who chose the traditional teacher preparation route may view teaching as a career to which they are committed. Those with an education degree may be more committed to teaching because they have fewer alternative career options than those with a maths or science degree. |

| Jacobson 1988 | Salary differentials | + recruitment (positive correlation between entry-level salary ranking and recruitment of highly qualified teachers + retention (positive correlation between salary ranking of mid-career teachers and retention of mid-career teachers) | It is correlational in design, it is not able to control for other confounding factors such as the economic and political differences in the districts |

| Jones 2004 | Mentoring | No effect No difference between the in-house and full-time mentoring in terms of teachers’ reported intention to stay (Cramer’s V effect size = 0.0067) No differences between the two groups in terms of reasons for leaving Lack of collaboration with colleagues and administrative and mentor support as top reasons for leaving | 1  Schools offering Full-Time mentoring programme were selected based on certain criteria, not randomised. Measure of retention was based on participants’ self-report. |

| Kelley 2004 | Induction and mentoring | Positive effect on retention | Compare 10 cohorts of new teachers with national average. These teachers were self-selected based on their qualifications and also they received higher salaries after completion than most novice teachers. The number involved in each year is small (under 50) |

| Kelly and Northrop | Teacher preparation | Teachers from less selective training colleges are less likely to leave their school (including moving school and leaving profession | Those from highly selective colleges may have greater job opportunities. Large amount of missing data. Very small sample from selective colleges. |

| Lawrason 2008 | Teacher induction | Some positive responses but weak links | Results collected from surveys of participants’ reported intention (compared with other induction programmes) Small sample of 54 |

| Lyons 2007 | Induction programme (known as left X programme) | + effect

| This study was based on a comparison of observed and predicted rates of retention using logistic regression analysis to control for observable characteristics. |

| McBride 2012 | Induction and mentoring | Positive effect Association between induction and mentoring variables, and likelihood of teacher remaining in teaching for the following year | Uses 3 admin datasets looking at the outcomes of those involved in induction and mentoring. |

| McGlamery and Edick 2004 | Teacher induction The CADRE project | Positive effect Compared with national sample (40% attrition rate), retention of CADRE participants was 89% over 5 years | 153 1st and 2nd year CADRE teachers Risk of selection bias |

| Mordan 2012 | Mentoring of beginning Career and Technical Education teachers | Positive effect on retention. Beginning CTE teachers assigned a mentor were 6.64 times more likely to remain in teaching | Uses 3 admin datasets (SASS, TFS and BTLS) Weak comparisons Small target group (N = 110) Focus of study was on teachers’ experience rather than retention outcomes |

| Morrell and Salomon (2017) | Scholarship scheme | Inconclusive | Claims that it was successful in assisting undergraduates with a STEM background into teaching, but not supported by the data |

| Murphy 2004 | Grow Your Own (A collaborative partnership with local education agencies, community colleges, private and public schools) | Positive effect Large percentage of participants who have received Consortium services have remained in continuous employment in North Carolina’s schools | Weak causal evidence Focus on participants in the Consortium programmes No comparison with non participants |

| Odell and Ferraro 1992 | Mentoring | + effect on retention | There was no control group and the groups were not matched nor was there an attempt to find similar, or matched districts to serve as the comparison. This is important since the districts in question might have already been higher-retaining districts (or at least higher than the state average. |

| Ogunyemi 2013 | Mentoring | Some claims about perceived impact of mentoring on retention | Self-report, no comparison group and high attrition |

| Oliver 2016 | Mentoring | Suggests that the use of social media platform increases retention of induction year maths teachers | Ethnographic accounts based on participant observations and field notes—not a study which aims to find causal/correlational outcomes linked to retention |

| Parker, Ndoye and Imig 2009 | Mentoring | Positive effect of same subject and grade level mentors on retention | Sample included 8838 beginning teachers being mentored for 2 years. Outcome was teachers’ intention to stay not actual retention |

| Partridge 2008 | Mentoring | No effect of mentoring on participants’ intention to stay | Survey based on 71 teachers (only 12 were assigned a mentor). The data was delimited to information provided by a portion of elementary teachers in one public school district so might not reflect the opinion of all members of the included population. Responses were subject to the validity of self-perceptions regarding mentoring. |

| Perry 2008 | Induction | Minority teachers | Small sample (n = 22). No clear data presented to make judgements about the validity of the findings |

| Protik et al., 2015 | Cash transfer incentive | No effect—uptake was low | 0 No comparison so not possible to say what the uptake would be in the absence of the incentive |

| Quartz 2003 | Induction and ongoing professional development in left X | Positive effect Over 5 years 70% of left X graduates remain in classroom compared to 61% nationally based on SASS (ES = 0.69) | Comparison with national figures Participants were self-selected (bias selection) The focus of the study is on the reason why teachers stay or leave |

| Randall 2009 | Mentoring | The teachers reported that the mentors had no effect on their decision to remain in the classroom. | Not impact evaluation. |

| Reynolds and Wang 2005 | Professional development | Positive effect PDS graduates less likely to leave teaching (20%) than non-PDS graduates (17%) ES = 0.26 | Compared PDS with non-PDS graduates High attrition/nonresponse |

| Reynolds, Ross and Rakow 2002 | Professional development | No effect No retention differences between PDS and non-PDS route | Small sample (N = 191) Attrition 58% No data on retention presented |

| Ridgely 2016 | Induction | Compare two models of induction. Suggests that dual-role induction was more effective in keeping teachers thana site-based induction. | Comparison was between 2 types of induction programme. No counterfactual. So cannot rule out other differences between the 2 districts who could have explained the different retention rates. There was also a huge disparity in numbers between the two districts being compared. |

| Robertson-Kraft 2014/2018 | Teacher performance management | Quicker turnover rates in INVEST pilot schools Paperwork relating to INVEST contributed to wanting to leave | Schools are not randomly allocated High non-response No report of actual retention data (based on teacher’s self-report) |

| Robertson-Phillips 2010 | Teacher induction Beginning Teacher Support and Assessment Program | No effect on retention Retention of BTSA teachers similar to the intern programme | Compared RIMS/BTSA teachers with intern teachers Groups not randomly assigned Data based on perceptions of participants |

| Rothstein (2015) | Types of contract (permanent vs temporary | No impact on supply. Bonus contract is less effective than the tenure contract in increasing the number of high ability teachers (ES +0.004 and +0.033 respectively). Retention policies are effective only if there is substantial increase in salary. If budget is fixed, may need to increase class sizes to offset the higher salary of teachers | The models are based on a number of caveats which are not possible in reality. It assumes that teacher performance assessment is unbiased and that new teachers are recruited from the same population as current teachers ignoring the fact that there are potentially high ability teachers who would not consider teaching at all. |

| Rogers 2015 | Induction | Found no link between induction programme and retention | Online survey, very low response (34%), no clear comparator. Evidence based on school leaders’ and administrators’ report. No actual retention data |

| Scott et al. (2006) | Scholarship, tuition fee remission and mentoring | + effect on recruitment (an increase of over 100% from in 37 1st year to 80 in the 3rd year). In the 4th year 100 enrolled 80% indicated that they would stay on. (no comparison group). Retention is based on participants’ self-report of intention to stay on the course, not teaching in general. | There is no comparison group, so it is not possible to attribute the increase in the number of students enrolled on the teacher certification course solely to the MASS programme. The retention rate is the retention on the programme and is based on students’ report of their intention rather than actual staying on |

| Shen, J. 1997 | Alternative route to teaching | Successful in recruiting minority and shortage subject teachers and increasing supply of teachers in urban areas However, AC teachers tend to have lower qualifications AC less successful in attracting experience personnel from other occupations Most new college graduates opted for the AC to avoid the traditional teacher education programme AC teachers less likely to treat teaching as a lifelong career No impact on retention (retention not measured but based on participants’ report of intention to stay) | Given that AC and TC teachers were not randomised there are important differences between them. Those who chose the AC route may have different motivations from those who chose the TC route. It’s also possible that those who entered via the AC route were not eligible for the TC programme because of their lower academic qualifications. |

| Shepherd 2009 | Claimed that the Induction program had a positive effect, but given the data presented, it is not possible to know if this can be attributed to the program. | Data gathered from stakeholders through surveys, focus group discussions and interviews. No causal/correlational evidence clearly presented. Poor reporting of samples. | |

| Sims (2017) | Salary compensation | + effect on recruitment and retention Increase in the total supply of teachers (recruitment deficit ES = 1.3 for science and 1.4 for maths | The model made a number of assumptions, e.g., Teachers missing in the School Workforce are taken to have left teaching, the reduction in probability of leaving the profession is evenly spread across each year of the policy, Increased pay does not incentivize more people to train in each cohort |

| Spuhler and Zetler 1993–1995 | Mentoring | Positive effect on retention. In the second year 92% of mentored teachers compared to 73% of non-mentored teachers were still teaching. Effect size is 0.12. In the 3rd year all the mentored teachers continued teaching but only 70% of non-mentored teachers remained in teaching (ES = 0.12) | The small sample size meant that the results could not be generalised. The comparison teachers were not matched in any way. |

| Stinebrickner 1998 | Wages | + impact on retention Teachers paid higher salary 9% more likely to stay on in teaching for more than 5 years than teachers paid the mean wage Attrition was 70%, hence the 1  | The data is poor with only 30% of teachers being tracked. We are therefore not sure how different the results would be if data for all the teachers were available. Those that did not respond are likely to be different to those who did. Also the survey asked teachers to recall their teaching experience. This can be subjective depending on their experience at the time of the survey and may not accurately reflect what actually happened. |

| Tai, Liu and Fan (2006) | Alternative certification of maths and science teachers | No difference between alternative and traditionally certified teachers | Used admin data (SASSand TFS) Missing data Lapse time between SASS and TFS is only one year. Longer evaluation needed to test sustained effect |

| Toterdell, Heilbronn, Bubb and Jones 2002 | Induction | Focused on the positive experience of NQTs | Not impact evaluation. Limited focus on retention or attempts to measure this in a coherent way. Looks at perceptions of new programme and some implementation but little in the way of actual outcomes. |

| Troutt 2014 | Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) | Claims PLCs improve retention | No pre- post comparison. Made conclusions based on comparison of a high retention and low retention school. The schools may be systematically different in terms of pupil intake, location etc, which could have influenced retention. Therefore, not possible to attribute success to the programme. Used school-level rather than individual teacher retention Poor reporting. |

| Uttley 2006 | Mentoring | Suggests positive effect | Evidence based on survey of teachers’ perceptions about the effectiveness of the programme, collected at one time point. Non response was 45%. |

| Van Overschelde, Saunders and Ash 2017 | Professional development programme Texas State University teacher preparation programme | Positive effect 85% of Texas State University’s graduates teaching after 5 years compared to 71% for average state retention rate (ES =0.9) Retention also higher. | Comparison institutions not randomly allocated. Did not control for teacher and institutional characteristics. |

| Wells 2011 | Financial incentives Team performance pay | No effect in the 1st and 2nd year | Difference-in-difference approach comparing retention before, during implementation and a year later Teachers’ report of retention and the district data not consistent |

| Wilkinson 2009 | Induction for alternative certification programme students | Comparisons were made with 7 different cohorts of students, who were lumped together as one despite possible differences in contexts/backgrounds. Evidence based on survey collecting respondents’ report of satisfaction with the programme and correlation analysis of their responses with their intention to stay | |

| Zavala 2002 | Alternative certification vs field-based training | CPDT (field-based training) appears to impact retention positively | Two types of teacher preparation not randomly assigned. So not sure how field-base training is compared to traditional teacher preparation. |

| Zhang and Zeller 2016 | Alternative routes into teaching | Long-term retention rates are greater for traditional certification programme than ACP | Small sample (58 teachers were tracked over 7 years. 22 regular, 20 lateral entry and 18 NC teachers. Groups self-selected not randomly assigned. |

| Zumwalt et al., 2017 | Alternative route to teaching |

| The evidence is weak as these measures were largely based on correlation and pre-post comparisons without any control. e.g., the increase in the proportion of qualified primary teachers coincided with the legislation that teachers should be qualified. |

References

- Sibieta, L. Teacher Shortages in England: Analysis and Pay Options; Education Policy Institute: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- DfE. School Workforce Census: Teachers Analysis Compendium 4; DfE: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen, S.; Plug, E.; Webbink, D. Teacher quality and student achievement: Evidence from a sample Dutch twins: Teacher quality and student achievement. J. Appl. Econom. 2016, 32, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goe, L. The Link between Teacher Quality and Student Outcomes: A Research Synthesis; National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, W.L.; Horn, S. Research findings from the Tennessee value-added assessment system (TVAAS) database: Implications for educational evaluation and research. J. Pers. Eval. Educ. 1998, 12, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, L.; Ladd, H. The Hidden Costs of Teacher Turnover; Working Paper No. 203-0918-1; National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER): Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton Trust. Improving the Impact of Teachers on Pupil Achievement in the UK—Interim Findings; Sutton Trust: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. Teaching Careers in Europe: Access, Progression and Support. Eurydice Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dee, T.; Goldhaber, D. Understanding and Addressing Teacher Shortages in the United States; Brookings: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aldeman, C. Teacher Shortage? Blame the Economy. TeacherPensionsorg. 2015. Available online: http://educationnext.org/teacher-shortage-blame-the-economy/ (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Ingersoll, R. Do we produce enough maths and science teachers? Phi Delta Kappan. 2011, 92, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, M. What Impact does the Wider Economic Situation Have on Teachers’ Career Decisions? A Literature Review; DfE Research Report DfE-RR136; DfE: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dolton, P.; Tremayne, A.; Chung, T. The Economic and Teacher Supply. A Paper Commissioned by the Education and Policy Division, OECD for the Activity Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers; OECD: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- See, B.H.; Gorard, S. Why don’t we have enough teachers? A reconsideration of the available evidence. Res. Pap. Educ. 2020, 35, 416–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lortie, D.C. Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, R.; Smith, T. The wrong solution to the teacher shortage. Educ. Leadersh. 2003, 60, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, H. One in Three Teachers Leaves within Five Years. Times Educational Supplement. 2019. Available online: https://www.tes.com/news/one-three-teachers-leaves-within-five-years (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Ingersoll, R. Is There Really a Teacher Shortage? University of Pennsylvania, Consortium for Policy Research in Education: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, R.; Perda, D. Is the supply of mathematics and science teachers sufficient? Am. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 47, 563–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcher, L.; Darling-Hammond, L.; Carver-Thomas, D. A Coming Crisis in Teaching? Teacher Supply, Demand and Shortages in the US; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Worth, J.; De Lazzari, G. Teacher Retention and Turnover Research. Research Update 1: Teacher Retention by Subject; NFER: Slough, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bowsher, A. Recruiting the ‘Best and Brightest’: Factors that Influence Academically-Talented Undergraduates’ Teaching-Related Career Decisions. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Glazerman, S.; Seifullah, A. An Evaluation of the Chicago Teacher Advancement Program (Chicago TAP) after Four Years. Final Report; Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fryer, R.G., Jr.; Levitt, S.D.; List, J.; Sadoff, S. Enhancing the Efficacy of Teacher Incentives through Loss Aversion: A Field Experiment (No. w18237); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Springer, M.G.; Ballou, D.; Hamilton, L.; Le, V.; Lockwood, J.; McCaffrey, D.; Pepper, M.; Stecher, B. Teacher Pay for Performance: Experimental Evidence from the Project on Incentives in Teaching. NCPI Policy Evaluation Report; National Center on Performance Incentives: Nashville, TN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, R.; May, H. Recruitment, Retention, and the Minority Teacher Shortage; University of Pennsylvania, Consortium for Policy Research in Education: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Gibson Research. Factors Affecting Teacher Retention: Qualitative Investigation. Research Report; DfE: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- DfE. Early Career Framework; DfE: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DfE. Teacher Recruitment and Retention Strategy; DfE: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, C. Is This Work Sustainable? Teacher Turnover and Perceptions of Workload in Charter Management Organizations. Urban Educ. 2014, 51, 891–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higton, J.; Leonardi, S.; Richards, N.; Choudhoury, A.; Sofroniou, N.; Owen, D. Teacher Workload Survey 2016; DfE: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, S.; Worth, J.; Bamford, S.; Wespieser, K. Engaging Teachers: NFER Analysis of Teacher Retention; NFER: Slough, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Perryman, J.; Calvert, G. What motivates people to teach, and why do they leave? Accountability, performativity and teacher retention. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2020, 68, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DfE. Analysis of School and Teacher Level Factors Relating to Teacher Supply; DfE: London, UK, 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/682023/SFR86_2017_Main_Text.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Figlio, D.; Kenny, L.W. Individual teacher incentives and student performance. J. Public Econ. 2007, 91, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanowski, A.T.; Longwell-Grice, H.; Saffold, F.; Jones, J.; Schomisch, K.; Odden, A. Recruiting New Teachers to Urban School Districts: What Incentives Will Work? Int. J. Educ. Policy Leadersh. 2009, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, C.D. Higher Pay in Hard-To-Staff Schools: The Case for Financial Incentives; Scarecrow Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goodnough, A.; Kelley, T. Newly certified teachers, looking for a job, find a paradox. New York Times, 1 September 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, D.; Lankford, H.; Loeb, S.; Wyckoff, J. Analyzing the Determinants of the Matching of Public School Teachers to Jobs: Estimating Compensating Differentials in Imperfect Labor Markets; Working Paper 9878; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek, E.; Kain, J.; Rivkin, S. Why public schools lose teachers. J. Human Resour. 2004, 39, 326–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibieta, L. The Teacher Labour Market in England: Shortages, Subject Expertise and Incentives; Education Policy Institute: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, S. What Happens When You Pay Shortage-Subject Teachers More Money? Simulating the Effect of Early-Career Salary Supplements on Teacher Supply in England; The Gatsby Charitable Foundation: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]