Multidimensional Aspect of Corporate Entrepreneurship in Family Business and SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ 1.

- Which variables are used to measure the multidimensionality of CE in family businesses and SMEs?

- RQ 2.

- What is the focus of the methodology and theory within CE for family businesses and SMEs regarding multidimensionality?

- RQ 3.

- How is the literature on CE in family businesses and SMEs developing?

- RQ 4.

- What are the theories used to explain CE in family businesses and SMEs?

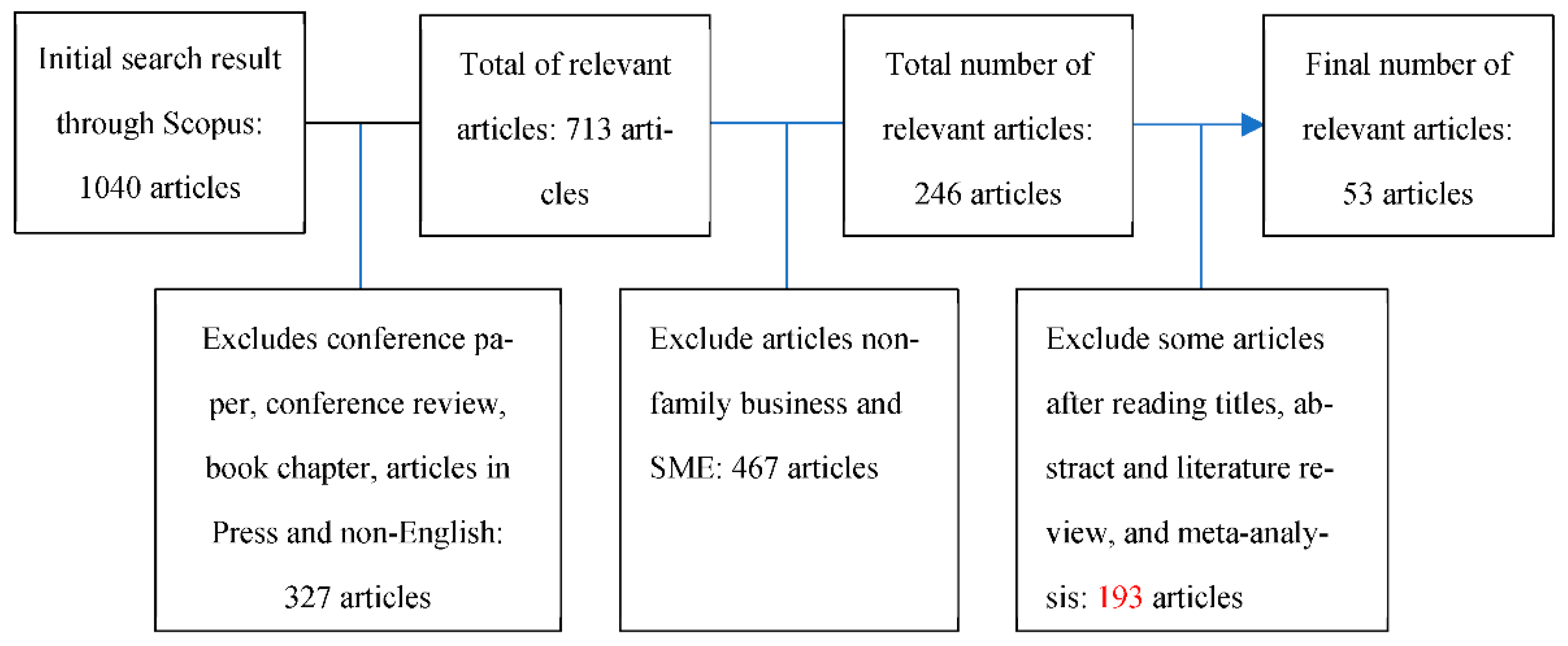

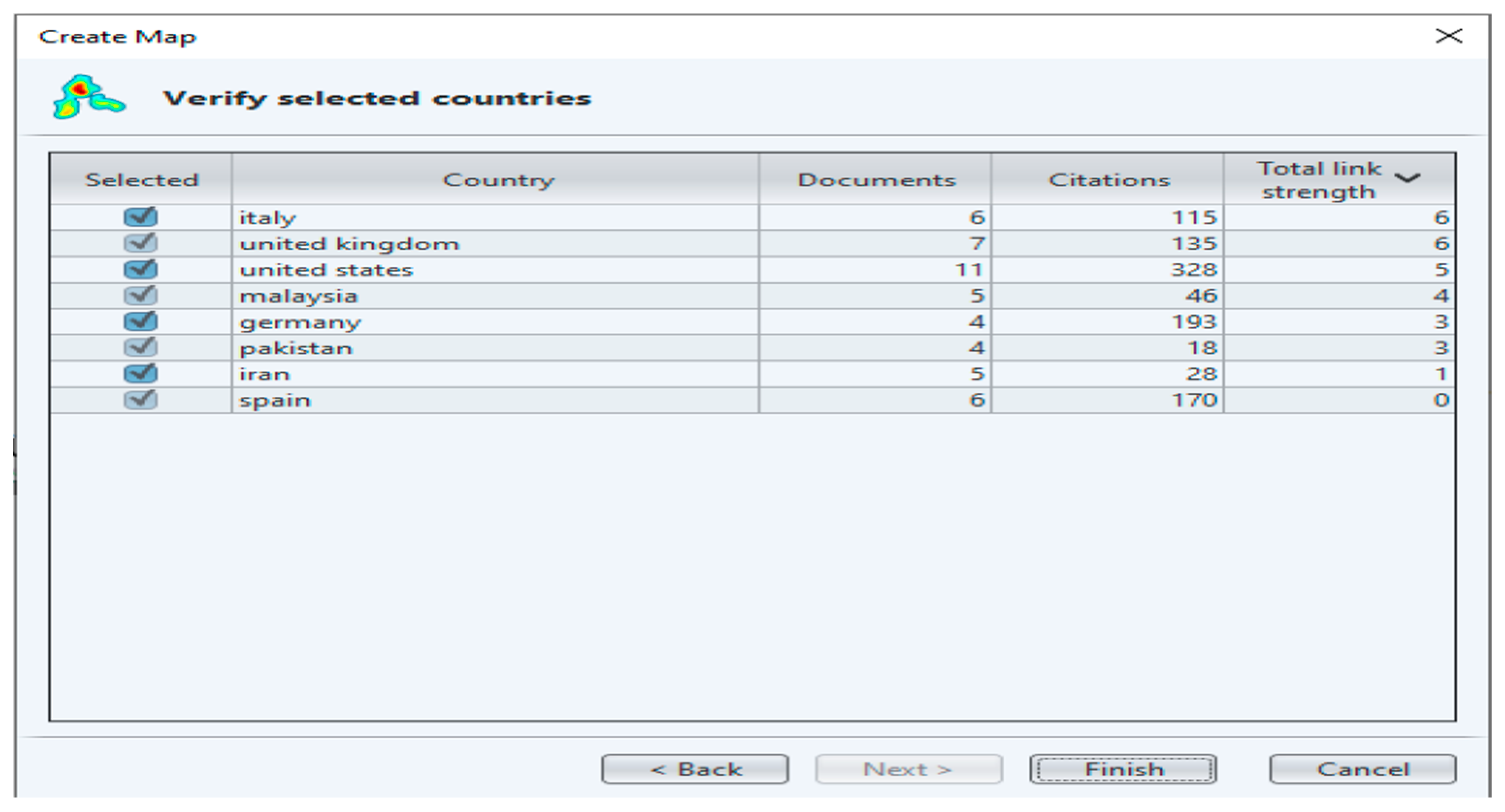

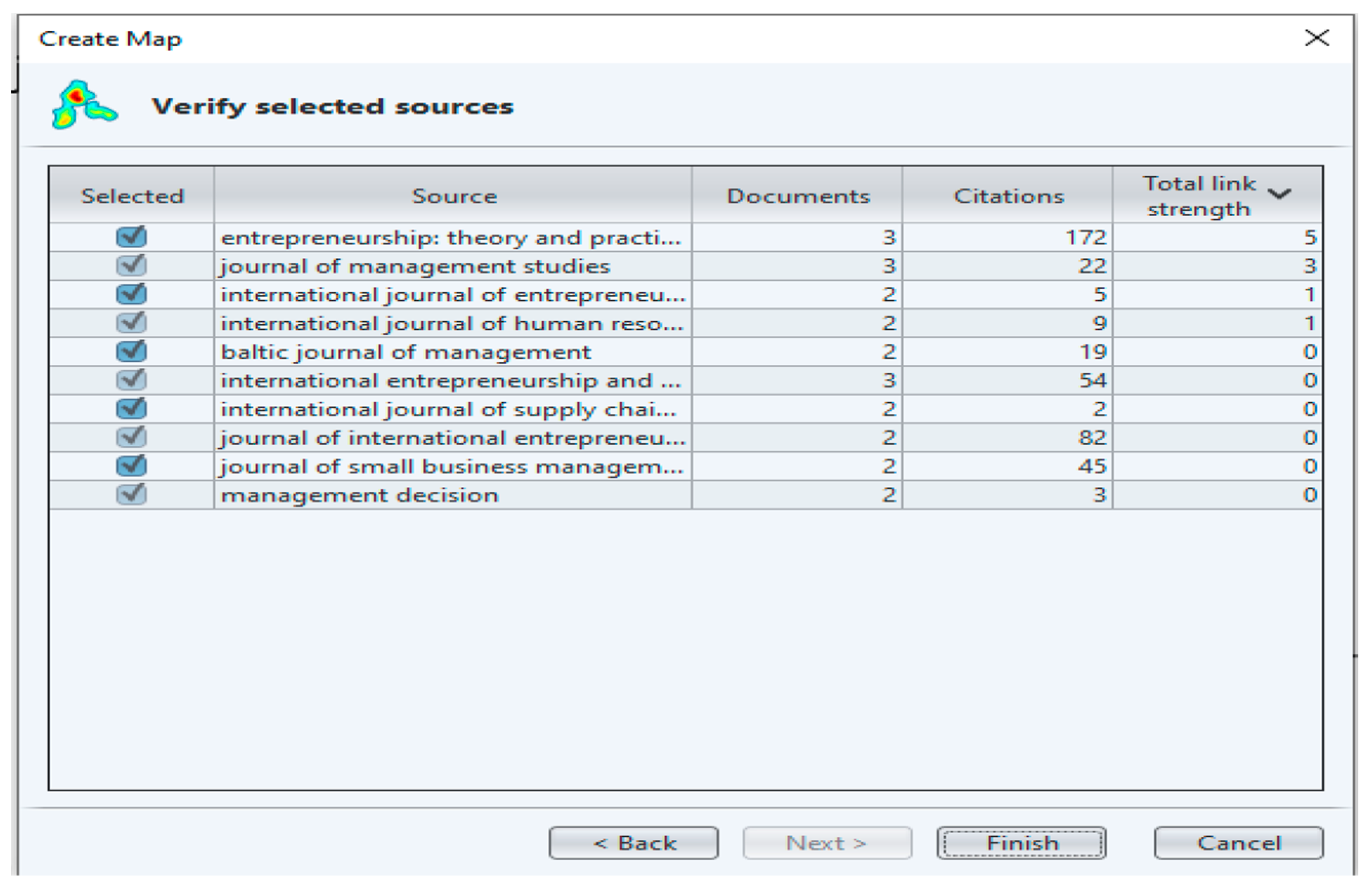

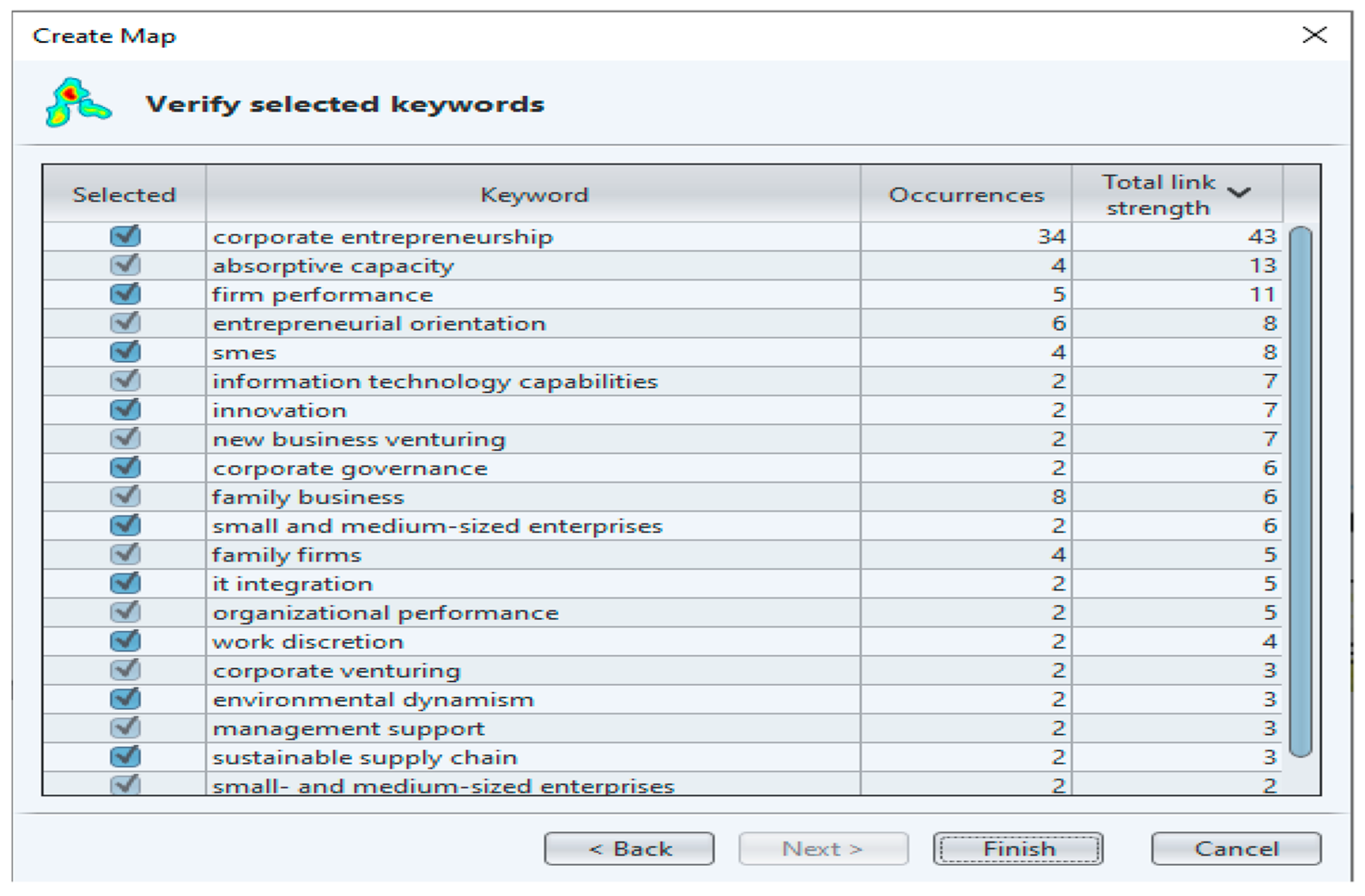

2. Methodology

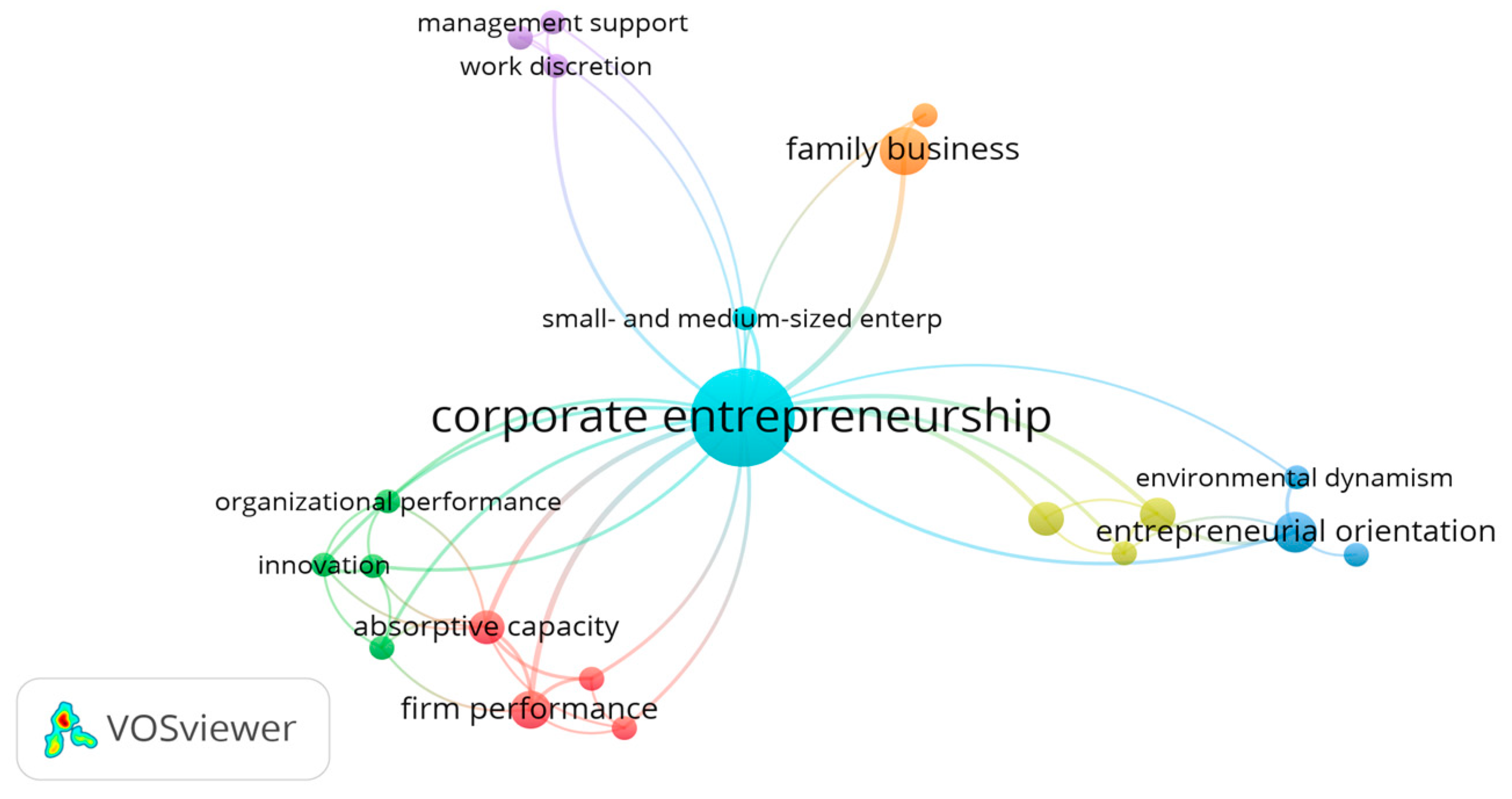

3. Results

3.1. Article Description

3.2. Articles Analysis

3.2.1. Actors Focus Analysis

3.2.2. Attribute Focus Analysis

3.2.3. Outcomes Focus Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Developing CE in Family Business and SMEs

4.2. The Theories in Literature of CE in Family Business and SMEs

5. Conclusions and Future Research

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aeknarajindawat, Natnaporn. 2020. Safety Climate Impact on the Safety Behavior in Chemical Industry of Thailand. Journal of Security and Sustainability 9: 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar Jahanshahi, Asghar, Khaled Nawaser, and Alexander Brem. 2018. Corporate Entrepreneurship Strategy: An Analysis of Top Management Teams in SMEs. Baltic Journal of Management 13: 528–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, Morteza, Kamal Sakhdari, and Mozhgan Danesh. 2020. Organizational preparedness for corporate entrepreneurship and performance in Iranian food industry. Journal of Agriculture, Science and Technology 22: 361–75. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85081019512&partnerID=40&md5=b028fdccf150dc638276033d780335d9 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Amberg, Joe J., and Sara L. McGaughey. 2019. Strategic Human Resource Management and Inertia in the Corporate Entrepreneurship of a Multinational Enterprise. International Journal of Human Resource Management 30: 759–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asogwa, Cosmas Ikechukwu, Osmund Chinweoda Ugwu, Anthonia Uju Uzuagu, Samson Ige Abolarinwa, Godwin Keres Okoro Okereke, Honesta Chidiebere Anorue, and Favour Amarachi Moghalu. 2020. Absorptive Capacity, Business Venturing and Performance: Corporate Governance Mediating Roles. Cogent Business and Management 7: 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azila-Gbettor, Edem M., Ben Q. Honyenuga, Marta M. Berent-Braun, and Ad Kil. 2018. Structural Aspects of Corporate Governance and Family Firm Performance: A Systematic Review. Journal of Family Business Management 8: 306–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojica, Ana Maria, María del Mar Fuentes-Fuentes, and Virginia Fernández Pérez. 2017. Corporate Entrepreneurship and Codification of the Knowledge Acquired from Strategic Partners in SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management 55: 205–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukamcha, Fayçal. 2019. The Effect of Transformational Leadership on Corporate Entrepreneurship in Tunisian SMEs. Leadership and Organization Development Journal 40: 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramer, Wichor M., Melissa L. Rethlefsen, Jos Kleijnen, and Oscar H. Franco. 2017. Optimal Database Combinations for Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews: A Prospective Exploratory Study. Systematic Reviews 6: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, Hong T. M., Huong T. M. Nguyen, and Vinh Sum Chau. 2020. Strategic Agility Orientation? The Impact of CEO Duality on Corporate Entrepreneurship in Privatized Vietnamese Firms. Journal of General Management 45: 107–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, Lennart, and Ivana Blažková. 2020. Internal Determinants Promoting Corporate Entrepreneurship in Established Organizations: A Systematic Literature Review. Central European Business Review 9: 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, Andrea, Tommaso Minola, Giovanna Campopiano, and Thilo Pukall. 2016. Turning Innovativeness into Domestic and International Corporate Venturing: The Moderating Effect of High Family Ownership and Influence. European Journal of International Management 10: 505–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jianhong, and Sucheta Nadkarni. 2017. It’s about Time! CEOs’ Temporal Dispositions, Temporal Leadership, and Corporate Entrepreneurship. Administrative Science Quarterly 62: 31–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chienwattanasook, Krisada, Samanan Wattanapongphasuk, Andi Luhur Prianto, and Kittisak Jermsittiparsert. 2019. Corporate Entrepreneurship and Business Performance of Logistic Companies in Indonesia. Industrial Engineering and Management Systems 18: 541–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, James J., Franz W. Kellermanns, Kam C. Chan, and Kartono Liano. 2010. Intellectual Foundations of Current Research in Family Business: An Identification and Review of 25 Influential Articles. Family Business Review 23: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucculelli, Marco, and Cristina Bettinelli. 2015. Business Models, Intangibles and Firm Performance: Evidence on Corporate Entrepreneurship from Italian Manufacturing SMEs. Small Business Economics 45: 329–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Massis, Alfredo, Kimberly A. Eddleston, and Paola Rovelli. 2021. Entrepreneurial by Design: How Organizational Design Affects Family and Non-Family Firms’ Opportunity Exploitation. Journal of Management Studies 58: 27–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddleston, Kimberly A., Franz W. Kellermanns, and Thomas M. Zellweger. 2012. Exploring the Entrepreneurial Behavior of Family Firms: Does the Stewardship Perspective Explain Differences? Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 36: 347–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Hanqing Chevy, Esra Memili, James J. Chrisman, and Linjia Tang. 2021. Narrow-Framing and Risk Preferences in Family and Non-Family Firms. Journal of Management Studies 58: 201–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, Mário, and Patricia Piceti. 2020. Family Dynamics and Gender Perspective Influencing Copreneurship Practices: A Qualitative Analysis in the Brazilian Context. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research 26: 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Ying, and Steven Si. 2018. Does a Second-Generation Returnee Make the Family Firm More Entrepreneurial?: The China Experience. Chinese Management Studies 12: 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, Encarnacion, Víctor Jesús García-Morales, and Rodrigo Martín-Rojas. 2018. Analysis of the Influence of the Environment, Stakeholder Integration Capability, Absorptive Capacity, and Technological Skills on Organizational Performance through Corporate Entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 14: 345–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, Robert P., and Tommie Welcher. 2018. Corporate Entrepreneurship as a Survival Routine. Advances in the Study of Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Economic Growth 28: 111–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, Robert, Shaunn Mattingly, Jeff Hornsby, and Alireza Aghaey. 2020. Impact of Relatedness, Uncertainty and Slack on Corporate Entrepreneurship Decisions. Management Decision 59: 1114–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedajlovic, Eric, Michael H. Lubatkin, and William S. Schulze. 2004. Crossing the Threshold from Founder Management to Professional Management: A Governance Perspective. Journal of Management Studies 41: 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, Maximiliano, Juan David Idrobo, and Rodrigo Taborda. 2019. Family Firms and Financial Performance: A Meta-Regression Analysis. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administracion 32: 345–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, William D., and Ari Ginsberg. 1990. Guest Editors’ Introduction: Corporate Entrepreneurship. Strategic Management Journal 11: 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hancer, Murat, Ahmet Bulent Ozturk, and Tugrul Ayyildiz. 2009. Middle-level hotel managers’ corporate entrepreneurial behavior and risk-taking propensities: A case of didim, Turkey. Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing 18: 523–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnátek, Milan. 2015. Entrepreneurial Thinking as a Key Factor of Family Business Success. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 181: 342–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hornsby, Jeffrey S., Donald F. Kuratko, Daniel T. Holt, and William J. Wales. 2013. Assessing a Measurement of Organizational Preparedness for Corporate Entrepreneurship. Journal of Product Innovation Management 30: 937–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, Jeffrey S., Donald F. Kuratko, Dean A. Shepherd, and Jennifer P. Bott. 2009. Managers’ Corporate Entrepreneurial Actions: Examining Perception and Position. Journal of Business Venturing 24: 236–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, Mojtaba, Hossein Dadfar, and Staffan Brege. 2018. Firm-Level Entrepreneurship and International Performance: A Simultaneous Examination of Orientation and Action. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 16: 338–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Mathew, and Michael Mustafa. 2017. Antecedents of Corporate Entrepreneurship in SMEs: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Journal of Small Business Management 55: 115–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure I. Introduction and Summary in this Paper WC Draw on Recent Progress in the Theory of (1) Property Rights, Firm. In Addition to Tying Together Elements of the Theory of E. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongwe, Antony I., Peter W. Moroz, Moses Gordon, and Robert B. Anderson. 2020. Strategic Alliances in Firm-Centric and Collective Contexts: Implications for Indigenous Entrepreneurship. Economies 8: 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keupp, Marcus Matthias, Maximilian Palmié, and Oliver Gassmann. 2012. The Strategic Management of Innovation: A Systematic Review and Paths for Future Research. International Journal of Management Reviews 14: 367–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwia, Rose Haynes, Kenneth M. K. Bengesi, and Daniel W. Ndyetabula. 2020. Succession Planning and Performance of Family-Owned Small and Medium Enterprises in Arusha City—Tanzania. Journal of Family Business Management 10: 213–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlar, Josip, and Philipp Sieger. 2019. Bounded rationality and bounded reliability: A study of nonfamily managers’ entrepreneurial behavior in family firms. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 43: 251–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuye, O. L., B. E. A. Oghojafor, and A. A. Sulaimon. 2012. Planning Flexibility and Corporate Entrepreneurship in the Manufacturing Sector in Nigeria. International Journal of Business Excellence 5: 323–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Rodríguez, Antonio L., Gema Albort-Morant, and Silvia Martelo-Landroguez. 2017. Links between Entrepreneurial Culture, Innovation, and Performance: The Moderating Role of Family Firms. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 13: 819–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Kyootai, Marianna Makri, and Terri Scandura. 2019. The Effect of Psychological Ownership on Corporate Entrepreneurship: Comparisons Between Family and Nonfamily Top Management Team Members. Family Business Review 32: 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, Anna. 2021. Interactions between Investments in Innovation and SME Competitiveness in the Peripheral Regions. Journal of International Studies 14: 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Yan, Zeki Simsek, Michael H. Lubatkin, and John F. Veiga. 2008. Transformational Leadership’s Role in Promoting Corporate Entrepreneurship: Examining the Ceo-Tmt Interface. Academy of Management Journal 51: 557–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Gordon, Ke Rong, and Wai Wai Ko. 2020. Promoting Employee Entrepreneurial Attitudes: An Investigation of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises. International Journal of Human Resource Management 31: 2695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G. Tom, and Gregory G. Dess. 1996. Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking It to Performance. Academy of Management Review 21: 135–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchisio, Gaia, Pietro Mazzola, Salvatore Sciascia, Morgan Miles, and J. Astrachan. 2010. Corporate venturing in family business: The effects on the family and its members. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 22: 349–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rojas, Rodrigo, Virginia Fernández-Pérez, and Encarnación García-Sánchez. 2017. Encouraging Organizational Performance through the Influence of Technological Distinctive Competencies on Components of Corporate Entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 13: 397–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, Maurizio, John Dumay, and Andrea Garlatti. 2015. Public sector knowledge management: A structured literature review. Journal of Knowledge Management 19: 530–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, Maurizio, John Dumay, and James Guthrie. 2016. On the Shoulders of Giants: Undertaking a Structured Literature Review in Accounting. Ccounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 29: 767–801. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, Deepa, Angappa Gunasekaran, Thanos Papadopoulos, and Benjamin Hazen. 2017. Green Supply Chain Performance Measures: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainable Production and Consumption 10: 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Michael. 2015. Providing Organisational Support for Corporate Entrepreneurship: Evidence from a Malaysian Family Firm. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 25: 414–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Michael, John J. Richards, and Hazel Melanie Ramos. 2013. High Performance Human Resource Practices and Corporate Entrepreneurship: The Mediating Effect of Middle Managers Knowledge Collecting and Donating Behaviour. Asian Academy of Management Journal 18: 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nabeel-Rehman, Rana, and Mohammad Nazri. 2019. Information technology capabilities and SMES performance: An understanding of a multimediation model for the manufacturing sector. Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management 14: 253–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, Swen, and Reinhard Prügl. 2021. Digital transformation: A review, synthesis and opportunities for future research. Management Review Quarterly 71: 233–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmulmunir, Nandang. 2020. Does reward enforcement and organization boundaries lead to sustainable supply chain performance in Indonesian SMEs? A moderating role of work discretion [Export Date: 13 July 2021]. International Journal of Supply Chain Management 9: 129–36. [Google Scholar]

- Naldi, Lucia, Leona Achtenhagen, and Per Davidsson. 2015. International Corporate Entrepreneurship among SMEs: A Test of Stevenson’s Notion of Entrepreneurial Management. Journal of Small Business Management 53: 780–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndemezo, Etienne, and Charles Kayitana. 2018. Corporate Governance, Corporate Entrepreneurship and Firm Performance: Evidence from the Rwandese Manufacturing Industry. Indian Journal of Corporate Governance 11: 103–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noerhartati, E., Y. Soesatyo, Cholik T. Mutohir Moedjito, and Amrozi Khamidi. 2020. Determinants of sustainable supply chain performance: The role of corporate entrepreneurship in indecision textile companies. International Journal of Supply Chain Management 9: 106–12. [Google Scholar]

- Poza, Ernesto J., and Mary S. Daugherty. 2014. Family Business. Cincinnati: South-Western Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Raitis, Johanna, Innan Sasaki, and Josip Kotlar. 2021. System-Spanning Values Work and Entrepreneurial Growth in Family Firms. Journal of Management Studies 58: 104–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Nabeel, Sadaf Razaq, Ammara Farooq, Nayab Mufti Zohaib, and Mohammad Nazri. 2020. Information Technology and Firm Performance: Mediation Role of Absorptive Capacity and Corporate Entrepreneurship in Manufacturing SMEs. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 32: 1049–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripollés-Meliá, María, Martina Menguzzato-Boulard, and Luz Sánchez-Peinado. 2007. Entrepreneurial Orientation and International Commitment. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 5: 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviezzo, Angelo, and Antonella Garofano. 2018. Accessing External Networks: The Role of Firm’s Resources and Entrepreneurial Orientation. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 34: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, Ana M., Zulima Fernández-Rodríguez, and Elena Vázquez-Inchausti. 2010. Exploring Corporate Entrepreneurship in Privatized Firms. Journal of World Business 45: 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, Ingrid, and Kenneth Bengesi. 2014. Dimensions of Entrepreneurial Orientation and Small and Medium Enterprise Performance in Emerging Economies. Development Southern Africa 31: 606–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhdari, Kamal, Henri Burgers, Jahangir Yadollahi Farsi, and Sasan Rostamnezhad. 2020. Shaping the Organisational Context for Corporate Entrepreneurship and Performance in Iran: The Interplay between Social Context and Performance Management. International Journal of Human Resource Management 31: 1020–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Irfan, Irfan Siddique, and Aqeel Ahmed. 2020. An Extension of the Socioemotional Wealth Perspective: Insights from an Asian Sample. Journal of Family Business Management 10: 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindehutte, Minet, Michael H. Morris, and Donald F. Kuratko. 2018. Unpacking Corporate Entrepreneurship: A Critique and Extension. Advances in the Study of Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Economic Growth 28: 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmelter, Ralf, René Mauer, Andreas Engelen, and Malte Brettel. 2010. Conjuring the Entrepreneurial Spirit in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: The Influence of Management on Corporate Entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing 2: 159–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secundo, Giustina, Pasquale Del Vecchio, and Gioconda Mele. 2021. Social Media for Entrepreneurship: Myth or Reality? A Structured Literature Review and a Future Research Agenda. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research 27: 149–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secundo, Giustina, Valentina Ndou, Pasquale Del Vecchio, and Gianluigi De Pascale. 2019. Knowledge Management in Entrepreneurial Universities: A Structured Literature Review and Avenue for Future Research Agenda. Management Decision 57: 3226–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, Glauciana Gomes, Vitor Lélio da Silva Braga, Carla Susana da Encarnação Marques, and Vanessa Ratten. 2021. Corporate Entrepreneurship Education’s Impact on Family Business Sustainability: A Case Study in Brazil. International Journal of Management Education 19: 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, Maryam, and Ali Shahnazari. 2013. Studying Effective Factors on Corporate Entrepreneurship: Representing a Model. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology 5: 1309–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, Amal Farouk. 2019. A Proposed Model for the Effect of Entrepreneurship on Total Quality Management Implementation: An Applied Study on Dairy and Juice Manufacturing Companies in Egypt. International Journal of Six Sigma and Competitive Advantage 11: 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriviboon, Chutikarn. 2020. Impact of selected factors on job performance of employees in it sector: A case study of Indonesia. Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues 9: 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopford, John M., and Charles W. F. Baden-Fuller. 1994. Creating Corporate Entrepreneurship. Strategic Management Journal 15: 521–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Nobin, Angela Randolph, and Alejandra Marin. 2020. A Network View of Entrepreneurial Cognition in Corporate Entrepreneurship Contexts: A Socially Situated Approach. Management Decision 58: 1331–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano, Nuria, David Urbano, and Marc Bernadich. 2010. Networks and corporate entrepreneurship: A comparative case study on family business in Catalonia. Journal of Organizational Change Management 23: 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, David, David Denyer, and Palminder Smart. 2003. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. British Journal of Management 14: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, Rene, and Mandla Adonisi. 2012. Antecedents of Corporate Entrepreneurship. South African Journal of Business Management 43: 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mehta, Mita. 2020. Effect of Leadership Styles on Corporate Entrepreneurship: A Critical Literature Review. Organization Development Journal 38: 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Villalonga, Belen, and Raphael Amit. 2006. How Do Family Ownership, Control and Management Affect Firm Value? Journal of Financial Economics 80: 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Lysander, and Dominik K. Kanbach. 2021. Toward an Integrated Framework of Corporate Venturing for Organizational Ambidexterity as a Dynamic Capability. Management Review Quarterly. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Shaker A. 1991. Predictors and Financial Outcomes of Corporate Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Business Venturing 6: 259–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyae, Babak, and Hossein Sadeghi. 2020. Exploring the relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and firm performance: The mediating effect of strategic entrepreneurship. Baltic Journal of Management 16: 113–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Actor | Variable | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior | Activities | ||

| Founder/CEO TMT/Manager Employee Family | Entrepreneurial orientation Entrepreneurial management Entrepreneurial leadership | Entrepreneurial leadership Entrepreneurial venturing Entrepreneurial innovation | Competitive advantage New products New ventures New markets/industries New business models New strategies Growth/survival diversification |

| Document per Year | Number of Articles | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Publication Per Year | ||

| 2007–2009 | 3 | 5.66 |

| 2010–2012 | 8 | 15.09 |

| 2013–2015 | 4 | 7.55 |

| 2016–2018 | 13 | 24.53 |

| 2019–2021 | 25 | 47.17 |

| Total articles | 53 | 100 |

| Research Approach | Number of Articles | Percentage |

| Quantitative | 41 | 77.36 |

| Qualitative | 8 | 15.09 |

| Mixed Methods | 4 | 7.55 |

| Total | 53 | 100 |

| Theory | Number of Articles | Percentage |

| Single theory | 30 | 73.17 |

| Multiple theories | 11 | 26.83 |

| Total | 41 | 100 |

| Single Theory | Multiple Theory |

|---|---|

| Behavioral theory (Fang et al. 2021) Prevailing theory (Soares et al. 2021) Prospect theory (Fang et al. 2021) Family system theory (Raitis et al. 2021) Contingency theory (De Massis et al. 2021) Stakeholder theory (Chienwattanasook et al. 2019; Saleem et al. 2020) Complementarity based theory (Rehman et al. 2020) Social exchange theory (Sakhdari et al. 2020) Gender theory (Franco and Piceti 2020) Organization theory (Leal-Rodríguez et al. 2017; Nabeel-Rehman and Nazri 2019; Sriviboon 2020) Network theory of entrepreneurship (Riviezzo and Garofano 2018; Akbari et al. 2020) Knowledge based resources theory (Bojica et al. 2017; Akbari et al. 2020) The classic theory of management (Noerhartati et al. 2020) Social information processing theory (Liu et al. 2020) Leadership theory (Boukamcha 2019) Echelon theory (Afshar Jahanshahi et al. 2018) Network theory (Hosseini et al. 2018) Institutional theory (Toledano et al. 2010; Hughes and Mustafa 2017) Dynamic capabilities theory (Martín-Rojas et al. 2017) Time, interaction, and Performance (TIP) theory (Chen and Nadkarni 2017) Stewardship theory (Eddleston et al. 2012) Entrepreneurship theory (Hancer et al. 2009; Marchisio et al. 2010; Van Wyk and Adonisi 2012; Garrett and Welcher 2018; Najmulmunir 2020) Business model innovation theory (Cucculelli and Bettinelli 2015) Stevenson’s theory (Naldi et al. 2015) System theory (Schmelter et al. 2010) International corporate entrepreneurial theory (Ripollés-Meliá et al. 2007) | Resource-based view theory and institutional theory (Ziyae and Sadeghi 2020) Behavioral theory and social comparison theory (Thomas et al. 2020) Resource-based and agency theory (Fu and Si 2018; Asogwa et al. 2020) Agency theory and dynamic capability theory (García-Sánchez et al. 2018) Agency theory and stewardship theory (Amberg and McGaughey 2019; Kotlar and Sieger 2019; Lee et al. 2019; Bui et al. 2020) Agency theory and transaction cost theory (Ndemezo and Kayitana 2018) Agency theory, stewardship theory and resource-based theory (Calabrò et al. 2016) Leadership and agency theory (Ling et al. 2008) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wahyudi, I.; Suroso, A.I.; Arifin, B.; Syarief, R.; Rusli, M.S. Multidimensional Aspect of Corporate Entrepreneurship in Family Business and SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review. Economies 2021, 9, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040156

Wahyudi I, Suroso AI, Arifin B, Syarief R, Rusli MS. Multidimensional Aspect of Corporate Entrepreneurship in Family Business and SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review. Economies. 2021; 9(4):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040156

Chicago/Turabian StyleWahyudi, Indra, Arif Imam Suroso, Bustanul Arifin, Rizal Syarief, and Meika Syahbana Rusli. 2021. "Multidimensional Aspect of Corporate Entrepreneurship in Family Business and SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review" Economies 9, no. 4: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040156

APA StyleWahyudi, I., Suroso, A. I., Arifin, B., Syarief, R., & Rusli, M. S. (2021). Multidimensional Aspect of Corporate Entrepreneurship in Family Business and SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review. Economies, 9(4), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040156