Racial Inclusion in Education: An Australian Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

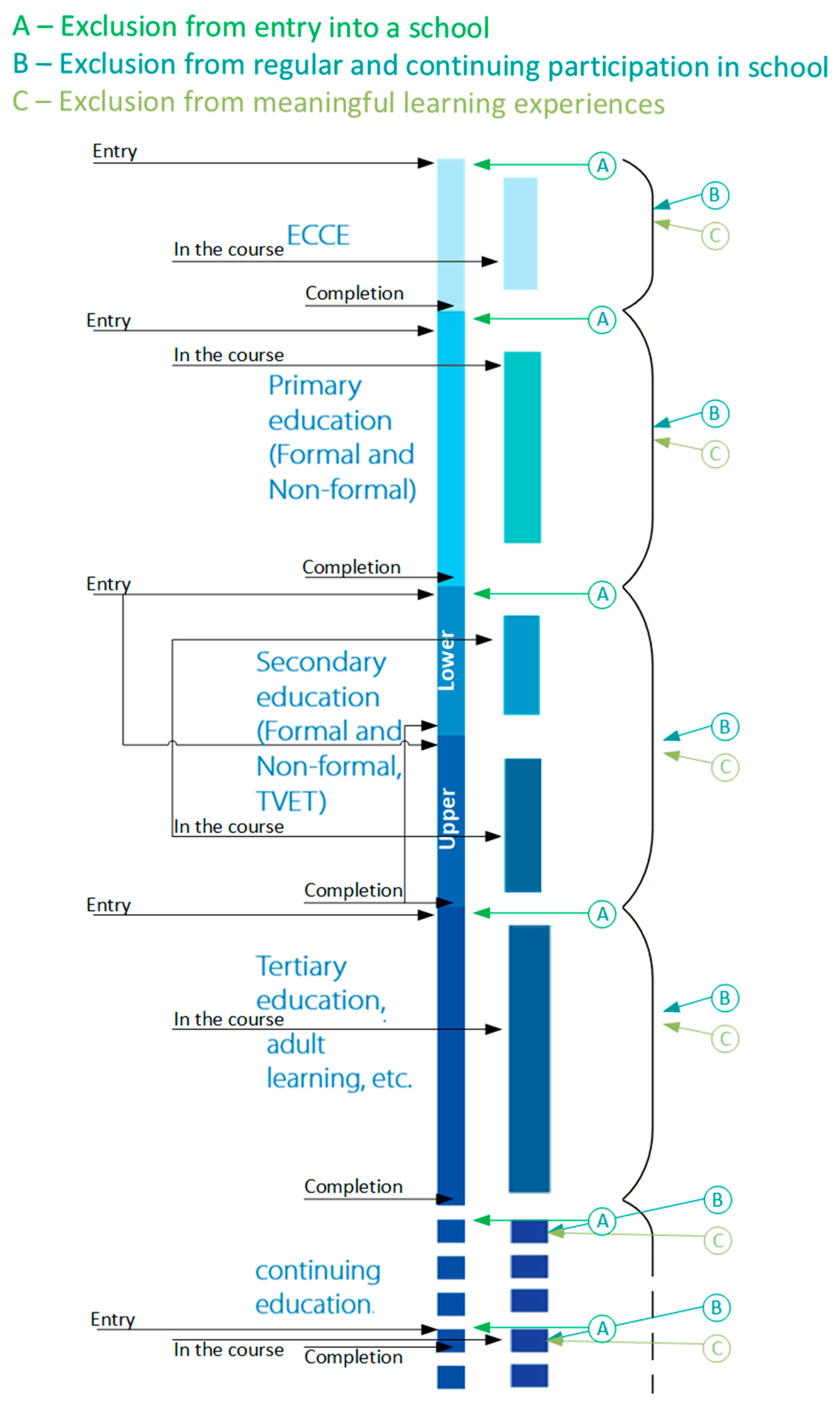

2. Exclusion in Education and Racism

“Inclusion is a process that helps overcome barriers limiting the presence, participation and achievement of learners. Equity is about ensuring that there is a concern with fairness, such that the education of all learners is seen as having equal importance.”

“Racism is an ideology that gives expression to myths about other racial and ethnic groups that devalues and renders inferior those groups that reflects and is perpetuated by deeply rooted historical, social, cultural and power inequalities in society.”

- Entry exclusion—for example, a student’s cultural attire other than the school uniform is considered against the policy and prohibited by the school.

- Regular and continuing participation exclusion—for example, a student is unable to attend school on specific days due to religious or life demands.

- Meaningful learning exclusion—for example, the language of instruction or discouraging experiences like bullying at school could make the environment non-conducive for student learning.

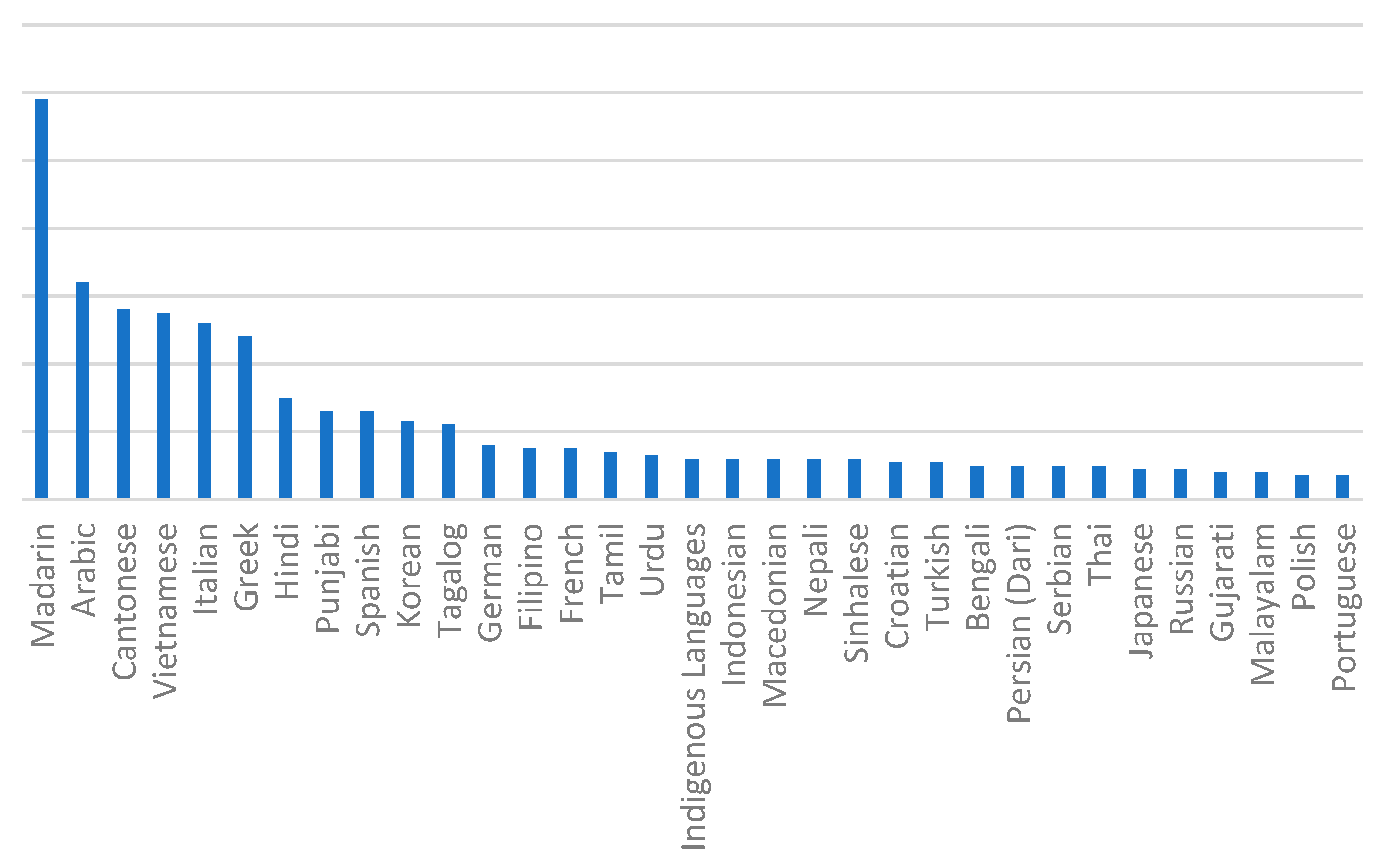

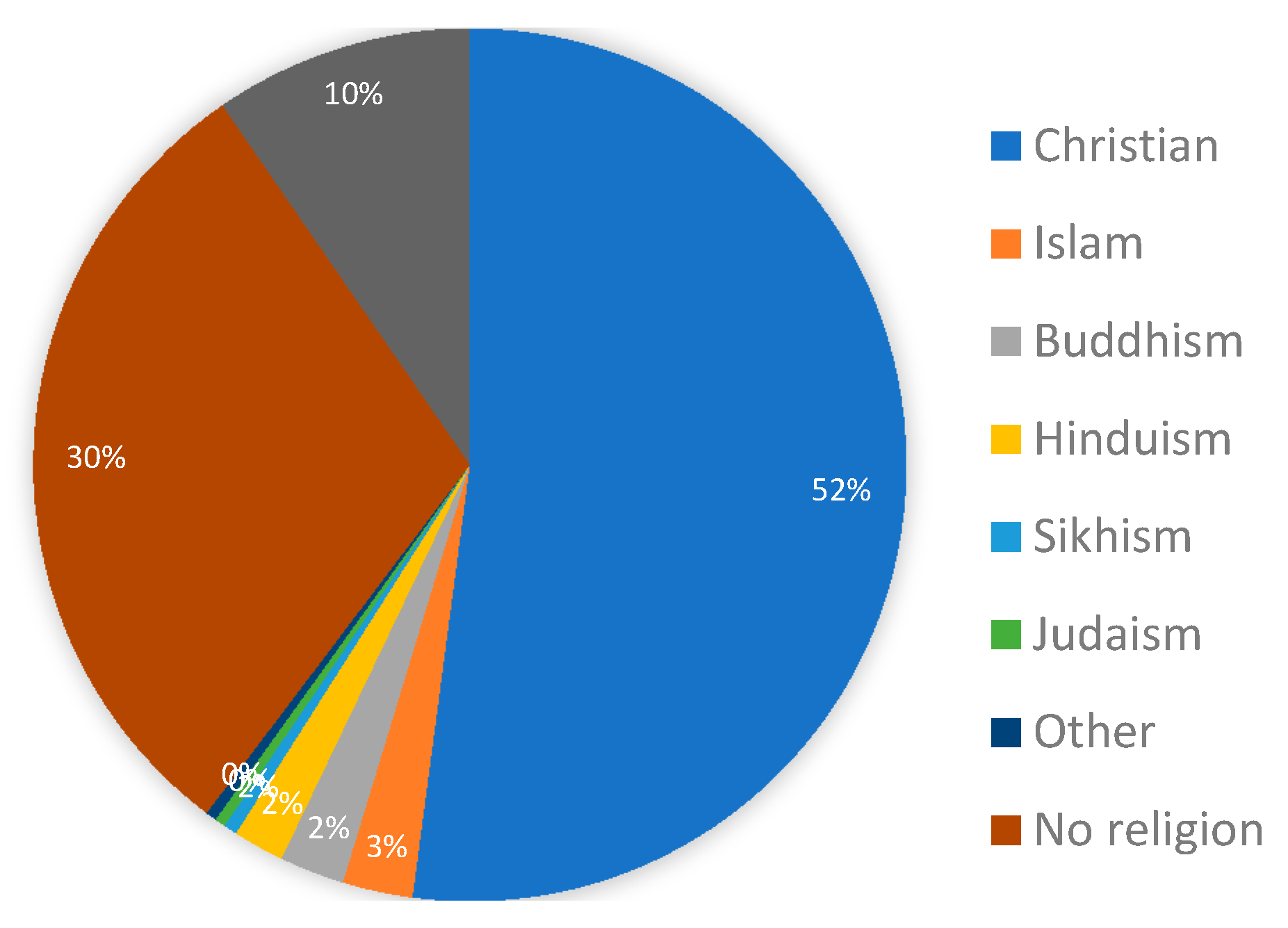

3. Diversity in the Australian Context

4. Factors of Racial Discrimination

5. Education System Framework to Address Racism

- ▪

- Macro-National level—involves changes in the legal and public policies,

- ▪

- Meso-Organizational level—involves management strategies in various schools

- ▪

- Micro-Individual level—involves approaches undertaken by the students.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abawi, Lindy-Anne, Cheryl Bauman-Buffone, Clelia Pineda-Báez, and Susan Carter. 2018. The Rhetoric and Reality of Leading the Inclusive School: Socio-Cultural Reflections on Lived Experiences. Education Sciences 8: 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABS. 2016. 2071.0—Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia—Stories from the Census. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/2071.0 (accessed on 19 January 2019).

- Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). 2012. National School Improvement Tool 2012. Melbourne: ACER. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Joanna, and Christopher Boyle. 2015. Inclusive education in Australia: rhetoric, reality and the road ahead. Support for Learning 3: 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auld, Glenn. 2018. Is There a Case for Mandatory Reporting of Racism in Schools? The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 47: 146–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. 2005. Disability Standards for Education 2005; Canberra: Department of Education and Training.

- Baak, Melanie. 2018. Racism and Othering for South Sudanese heritage students in Australian schools: is inclusion possible? International Journal of Inclusive Education 23: 125–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Zinzi D., Nancy Krieger, Madina Agénor, Jasmine Graves, Natalia Linos, and Mary T. Bassett. 2017. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 389: 1453–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagetti, Marco, and Sergio Scicchitano. 2011. Education and wage inequality in Europe. Economics Bulletin 31: 2620–28. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore, Jill. 2007. Equity and Social Justice in Australian Education Systems: Retrospect and Prospect. In International Handbook of Urban Education. Basel: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bodkin-Andrews, Gawaian, and Bronwyn Carlson. 2016. The legacy of racism and Indigenous Australian identity within education. Race Ethnicity and Education 19: 784–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budria, Santiago. 2010. Schooling and the distribution of wages in the European private and public sectors. Applied Economics 42: 1045–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambridge Dictionary. 2019. Exclusion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/exclusion (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Cameron, Lindsey, and Adam Rutland. 2016. Researcher–Practitioner Partnerships in the Development of Intervention to Reduce Prejudice Among Children. In The Wiley Handbook of Developmental Psychology in Practice. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Evelyn R., and Mary C. Murphy. 2015. Group-based differences in perceptions of racism: what counts, to whom, and why? Social and Personality Psychology Compass 9: 269–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingano, Federico. 2014. Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth. Working Papers OECD. Paris: Social, Employment and Migration. [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Montoya, Lucas, and Marta Catalina Castro-Martínez. 2016. Disability and Social Inclusion in Colombia. Bogotá: Saldarriaga-Concha Foundation Press, p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- De Plevitz, Loretta. 2007. Systemic racism: the hidden barrier to educational success for Indigenous school students. Australian Journal of Education 51: 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD). 2010. Building Respectful and Safe Schools, State of Victoria. Available online: http://www.eduweb.vic.gov.au/edulibrary/public/stuman/wellbeing/respectfulsafe.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- DET. 2010. Racism No Way. Darlinghurst: Department of Education and Training, Available online: http://www.racismnoway.com.au/about-racism/timeline/index-2000s.html (accessed on 3 July 2018).

- Dunn, Kevin M., Garth L. Lean, Megan Watkins, and Greg Noble. 2014. The Visibility of Racism: Perceptions of Cultural Diversity and Multicultural Education in State Schools. The International Journal of Organizational Diversity 15: 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, James, and Kevin Dunn. 2006. Racism and Intolerance in Eastern Australia: A geographic perspective. Australian Geographer 37: 167–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, James, and Kevin Dunn. 2007. Constructing Racism in Sydney, Australia’s Largest EthniCity. Urban Studies 44: 699–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, Diane. 2008. Islamophobia: Examining causal links between the media and “race hate” from “below”. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 28: 564–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, Brown. 2009. Racism in Australia. Available online: http://www.abc.net.au/unleashed/31004.html (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- Henrietta, Cook. 2018. There Was an Assumption I Needed Help’: Racism in our Schools. The Age. Available online: https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/there-was-an-assumption-i-needed-help-racism-in-our-schools-20180120-h0lfkl.html (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- Ikuenobe, Polycarp. 2010. Conceptualizing Racism and Its Subtle Forms. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 41: 161–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtoual, Alia Salem. 2006. They don’t want us to practice our faith: Young South Australian Muslim women & their experiences of religious racism in high school. In AARE 2006 International Education Research Conference. Adelaide: Australian Association for Research in Education. [Google Scholar]

- Jahnukainen, Markku. 2015. Inclusion, Integration, or What? A Comparative Study of the School Principals’ Perceptions of Inclusive and Special Education in Finland and in Alberta, Canada. Disability & Society 30: 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jaumotte, Florence, Subir Lall, and Chris Papageorgiou. 2013. Rising Income Inequality: Technology, or Trade and Financial Globalization? IMF Economic Review 61: 271–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, Michèle, Stefan Beljean, and Matthew Clair. 2014. What is missing? Cultural processes and causal pathways to inequality. Socio-Economic Review 12: 573–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, Ann, Marisa Gillies, Peter J. Howard, and Juli Coffin. 2007. It’s enough to make you sick: the impact of Racism on the health of Aboriginal Australians. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 31: 322–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Tené T., Courtney D. Cogburn, and David R. Williams. 2015. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 11: 407–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclean, Rupert. 2017. Life in Schools and Classrooms: Past, Present and Future. Singapore: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri, Fethi, Louise Jenkins, and Lucas Walsh. 2012. Racism and its impact on the health and wellbeing of Australian youth: empirical and theoretical insights. Education and Society 30: 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, Pedro S., and Pedro T. Pereira. 2004. Does education reduce wage inequality? Quantile regressions evidence from 16 countries. Labour Economics 11: 355–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, Brenda. 2007. Educational administrators’ conceptions of whiteness, anti-racism and social justice. Journal of Educational Administration 45: 684–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincer, Jacob. 1974. Schooling, Experience and Earnings. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Miškolci, Jozef, Derrick Armstrong, and Ilektra Spandagou. 2016. Teachers’ Perceptions of the Relationship between Inclusive Education and Distributed Leadership in Two Primary Schools in Slovakia and New South Wales (Australia). Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability 18: 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradies, Yin. 2016. Colonisation, racism and indigenous health. Journal of Population Research 33: 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradies, Yin, Jehonathan Ben, Nida Denson, Amanuel Elias, Naomi Priest, Alex Pieterse, Arpana Gupta, Margaret Kelaher, and Gilbert Gee. 2015. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 10: e0138511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, Naomi, Tania King, Laia Bécares, and Anne M. Kavanagh. 2016. Bullying Victimization and Racial Discrimination Among Australian Children. American Journal of Public Health 106: 1882–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, Fazal. 1997. Beyond the East-West Divide: Education and The Dynamics of Australia-Asia Relation. Australian Educational Researcher 24: 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, Hayley, and Bruno Zeller. 2011. Indirect Systemic Discrimination in Education: A Comparative Analysis. Macquarie Journal of Business Law 8: 111–33. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, S., and Andreotti V. De Oliveira. 2018. What Does Theory Matter? Conceptualizing Race Critical Research. The Relationality of Race in Research. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, Jawad, and Robin Kramar. 2010. What is the Australian model for managing cultural diversity? Personnel Review 39: 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szoke, Helen. 2012. Racism Exists in Australia—Are We Doing Enough to Address It? Australian Human Rights Commission. Available online: http://humanrights.gov.au/about/media/speeches/race/2012/20120216_Racism_exists.html#fn16 (accessed on 29 June 2018).

- Taylor, J. Edward, Mateusz J. Filipski, Mohamad Alloush, Anubhab Gupta, Ruben Irvin Rojas Valdes, and Ernesto Gonzalez-Estrada. 2016. Economic Impact on Refugees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 7449–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The United Nations. 2006. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Treaty Series 2515, Article 44. New York: The United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Deborah A., and M. Kamari Clarke. 2013. Globalization and race: Structures of inequality, new sovereignties, and citizenship in a neoliberal era. Annual Review of Anthropology 42: 305–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülger, Zuhal, Dorothea E. Dette-Hagenmeyer, Barbara Reichle, and Samuel L. Gaertner. 2018. Improving outgroup attitudes in schools: A meta-analytic review. Journal of School Psychology 67: 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2012. Addressing Exclusion in Education A Guide to Assessing Education Systems Towards More Inclusive and Just Societies. Programme Document ED/BLS/BAS/2012/PI/1. Available online: www.unesco.org (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- UNESCO Education Sector. 2017. A Guide for Ensuring Inclusion and Equity in Education. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- VicHealth. 2007. Making the Link between Cultural Discrimination and Health, Issue No. 30. Available online: www.vichealth.vic.gov.au (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- Viruell-Fuentes, Edna A., Patricia Y. Miranda, and Sawsan Abdulrahim. 2012. More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Social Science & Medicine 75: 2099–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Kyung-Eun, and Seung-Hwan Ham. 2017. Truancy as systemic discrimination: Anti-discrimination legislation and its effect on school attendance among immigrant children. The Social Science Journal 54: 216–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Names | Description | Experience |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Structure | School Policies and Practices that, intentionally or unintentionally, are directly or indirectly biased. | A Sikh schoolboy was denied enrolment in a school because he could not adhere to the school uniform due to a religious rule (De Plevitz 2007). |

| Race | Student’s racial background makes them inferior/superior. | A South Sudanese student was teased and harassed at school because of the difference in background (Henrietta 2018). |

| Colorism | Whiteness is a physical descriptor and a privilege that enable whites to maintain power and control in school. | A female student was harassed by her peers for having dark skin and resulted in having no friends (DET 2010; McMahon 2007). |

| Non-English-Speaking Background (NESB) | Both NESB students and teacher observe biased attitudes about their English language competence and learning abilities, qualifications and progress opportunities. | An Afghan student was abused by a peer about his manner of speech and accent (Mansouri et al. 2012). |

| Religion | Student different religious beliefs mark them superior or inferior. | Female students wearing hijab are marked to be passive female due to hijab being considered as a symbol of the gender oppression (Imtoual 2006). |

| Social and Economic Status | Students judged by where they live, how rich they are and so on. | Any robbery incidence at school results in suspecting a black-skinned student straightaway due to their link to poverty (Mansouri et al. 2012). |

| Reverse racism | Students from minorities become prominent and biased against majority or other groups. | An Anglo-Saxon student in a class with a majority of Vietnamese students and teachers felt being deliberately excluded (Mansouri et al. 2012). |

| Lack of Knowledge | On school staff and teacher’s part, lack of cross-cultural and beliefs understanding and awareness Student’s lack of unfamiliarity about other races and beliefs | A Burundian black girl, felt racially humiliated and excluded when the teacher laughed with other students while reading a story book about a black man and a white woman (Mansouri et al. 2012). |

| Macro-National Level | Meso-Organizational Level | Micro-Individual Level |

|---|---|---|

| Australian Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (RDA) to Elimination of all Forms of Racism | Anti-racism policy of schools as part of a general Behavior Management Policy or Discipline Policy or standalone | Student and their parents are educated to be aware of their own rights about racist acts |

| The Public Service Act 1999 (PSA) to manage diversity | Educational session for school staff and students - educate counter racism - attain cross-culture knowledge - get professional development | Bystander Training to behave in a supportive way to students who are being victims |

| National Anti-Racism Strategy 2012 and The People of Australia—Australia’s Multicultural Policy should be linked to multiculturalism | Promotion of social behavior by - being role models as a Teacher and as a School - celebrating Multicultural events and encouraging participation. - giving incentives and certificates for good behavior | Assertiveness Training to respond assertively and requires the student to be respectful towards themselves and others equally |

| Government taking steps to eliminate racism and racial discrimination e.g., - Parliament passes legislation to recognize Indigenous people as Land owners - Apology to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander as Stolen Generations - Multicultural E-forum - Social Inclusion Week | Prevention of racial action by - designing curriculum content to develop social skills relevant to counter racism - engaging Students in constructive activities and reducing opportunities for racial behavior e.g., rigorous monitoring - using playground programs - encouraging anti-bullying committees of students - Using ‘no-blame approaches’ | Restorative practices to repair any harm made to relationships Students stand against the racial activities |

| Provision of information and resources for schools to tackle racial problems effectively e.g., video on ‘Bullying—no way!’ | Supporting victims provides assistance who are involved by both teachers and students e.g., Buddy systems | Encourage students who volunteer to tackle racial problems Students feel good about their racial heritage |

| Publicizing certain community groups that have worked with schools e.g., Buddy Bear School Program | Involving parents to counter Racism through - friendly Schools and Families program - developing policies - encouraging their children to cherish their culture and language | Involving student leaders to propagate inclusiveness |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fahd, K.; Venkatraman, S. Racial Inclusion in Education: An Australian Context. Economies 2019, 7, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies7020027

Fahd K, Venkatraman S. Racial Inclusion in Education: An Australian Context. Economies. 2019; 7(2):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies7020027

Chicago/Turabian StyleFahd, Kiran, and Sitalakshmi Venkatraman. 2019. "Racial Inclusion in Education: An Australian Context" Economies 7, no. 2: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies7020027

APA StyleFahd, K., & Venkatraman, S. (2019). Racial Inclusion in Education: An Australian Context. Economies, 7(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies7020027