1. Introduction

Migration has become an important branch of literature in the fields of labor economics, economic growth, and economic development. The focus of the research on migration has mostly been on individuals seeking to work abroad. But recently, literature focusing on the mobility of students is emerging.

The obvious reason for this growing body of research is that the mobility of students has increased: According to OECD, the mobility of students has significantly risen in the past four decades: from 250,000 in 1965 to 1.1 million in 1980 and to 4.5 million in 2012. Moreover, over the last decade, the rate of students entering OECD countries was twice that of flows for the purpose of finding employment.

1Moreover, while mobility of students up until now was mostly a phenomenon of temporary migration, nowadays, the purpose of mobility of students has changed: There is a rise in the number of international students who remain in the country where they completed their studies.

2 This increase in permanent migration of students leads to changes in the analysis of migration, and migration research focuses not only on individuals who have made the decision to work abroad, but also to study abroad. In consequence, there is a new literature linking migration of workers to migration of students.

This paper is part of this new literature. The paper develops a simple two-step model that describes the decisions of an individual vis-à-vis education and migration, and presents a “unified model”, wherein the two migration decisions are combined into a single, unique model. The main idea of the two-step model is that, as the employment decision is affected by the previous decision of where to study, it is best to analyze these two decisions in a unified model that includes these two steps.

This paper analyzes individuals’ optimal decisions by focusing on the costs and benefits of each of the alternatives. The benefits of the various alternatives are mainly a function of wages and human capital which in turn are driven by the quality of higher education.

Among the costs, this paper mainly focuses on psychological costs, and shows that psychological costs are an important element affecting which of these strategies is optimal. In this paper, we assume that the psychological costs differ between migrating when young versus older. This assumption enables us to analyze under which assumptions, it is optimal to relocate as a student and under which conditions it is optimal to relocate after having completed one’s studies, or what is known as ‘brain-drain’.

More specifically, our model shows that since psychological costs increase with age, the heretofore brain drain strategy is sub-optimal, and therefore in countries where young people can afford to go abroad for their education, it is optimal to do so.

However, they are still countries wherein it is very costly to go abroad to acquire an education, or even impossible to get admitted to foreign universities; in those cases, the brain-drain strategy is optimal. Still, over time, globalization reduces costs and is therefore leading to students migrating, mostly to OECD countries. But in the future, student migration will likely become a global phenomenon.

Therefore, it is important to note that brain drain—which was (and is) optimal for individuals from poor countries—will be replaced by the strategy we propose in our model: migrating while a student.

The second part of the paper is empirical. Our empirical work stresses that there is a concentration effect. We find that not only does higher-education quality affect migration, but that the flow of students is concentrated towards countries with high quality higher education.

In the last part of the paper, we discuss the trade-off related to the usual brain drain. On the one hand, the students who move to countries with high-quality universities have a better chance of climbing the mobility ladder. On the other hand, if they do not return to their home country, the home country has lost its young people, which will lead to lower economic growth.

This paper is organized as follows: In the next section, we present a short overview of the literature. In

Section 3 we develop the model of migration. In the fourth section, we present some empirical regularities.

Section 5 concludes.

2. Related Literature

One of the main assumptions of our model concerns the relationship between the magnitude of psychological factors and age of migration. Therefore, we first present the literature on this subject. Then, we present the literature on mobility of students.

2.1. Psychological Costs

Psychological costs are affected by many diverse variables. First are the “separating-family” costs. Already Sjaastad (1962) [

7] stressed that migrants bear costs which result from separation from family and friends including costs of loneliness and isolation; these are the ‘separating-family’ costs. Psychological costs also include the costs of leaving one’s own culture and adapting to the new one. These costs are due to the cultural differences between the sending and the receiving countries.

This phenomenon of adapting to a new culture is coined as acculturation (see, Berry, 1997 [

8]; Narchal, 2007 [

9]). Theories of acculturation stress that the interaction between different cultures and adaptation to the majority’s culture, lead to a process in which migrants are losing their own cultural identity.

3 Therefore, the extent of these costs depends on the cultural differences between the origin and the destination countries.

4 The extent of these costs are also influenced by differences in language, distance and even size of the migrant population due to network effect (see Beine et al., 2014 [

12]).

There are also psychological costs which are not due to acculturation or to family “loss” but to stress of adapting to a new place, and finding a job. The success of finding a job and acclimating in a new country was shown to be influenced by one’s own fears and ex-ante beliefs. Schwarzer and Hahn (1995) [

13] show that these beliefs are evolving over time. They emphasize that moving while young to a new country decreases the subjective fears of migration. In other words, psychological costs are lower for young individuals.

5The effects of age influence also the ‘separating-family’ psychological costs. Indeed, Zaiceva and Zimmermann (2008 [

14], p.8) have checked migration of workers in Europe, and have shown that married individuals with children are expected to have lower willingness to migrate because of higher psychic costs of separation from their family. Moreover, Reagan and Olsen’s (2000) [

15] find lower acculturation costs for those who arrived at younger ages (see also Schmidt, 1994 [

16]; and Constant and Massey, 2002 [

17]).

On the other hand, we could argue that migrating after graduation makes the individual more mature to affront the various obstacles of migration.

6 However, the empirical literature stresses that psychological costs are lower when young. In consequence, in the model presented in next section, we assume that psychological costs are lower when moving before acquiring education than after.

2.2. Migration of Students

The literature on student flow is mainly empirical. Most of the papers outline the elements affecting the costs and benefits of students’ migration (see Kyung, 1996 [

18]; Heaton and Throsby, 1998 [

19]; Bessey, 2006 [

20]; Agasisti and Dal Bianco, 2007 [

21]; González et al., 2011 [

22]; and Abbott and Silles, 2015 [

23]).

7The main costs affecting migration decisions (ignoring psychological costs we focused above) are financial costs which are affected by distance, language, and tuition fees.

Two elements stressed in the literature as affecting the returns to migration are wages and quality of higher education. About wages, Mak and Moncur (2001) [

31] found that higher wages in the country of origin positively affect the rate of migration. It is so, because agents with higher income can bear the costs of migration more easily and have better possibilities to invest in high quality education.

The second variable affecting mobility of students is quality of university. Indeed, the discrepancy in education quality between foreign and domestic universities is stressed as one of the motivations for migration (see Gordon and Jallade, 1996 [

32]; and Szelenyi, 2006 [

33]). Haupt et al., (2013) [

34] analyze the brain drain vs. brain gain in a framework in which quality of higher education is endogenous. Van Bouwel (2009) [

35], and Thiessen and Ederveen (2006) [

36] also focus on quality of education, and take as proxy of quality the number of national universities among the top 200 in international rankings.

The literature on migration of students and higher education also focuses on the macro-decisions by governments. Poutvaara (2006) [

37] argued that while migration fosters private investment in human capital, it will lead to a reduction of public investment in education, due to free riding. Following this line of reasoning, Mechtenberg and Strausz (2008) [

38] underlines the tradeoff facing government, i.e., competition versus free riding. On the one hand, a central planner may decide to invest in quality of higher education in order to attract foreign students, and due to more competition, increases the amount of investment. On the other hand, the central planner might encourage local students to obtain education overseas free of charge. This free-riding on the account of another country reduces the total amount of investment in higher education. There are also studies on the effects of migration on the social environment as more migration might lead to a reduction in cultural differences over time (see Poutvaara, 2004 [

37]; and Mechtenberg and Strausz, 2008 [

38]).

Another pan of the literature combines decisions of working and learning. Already in the 1980s, Kwok and Leland (1982) [

39] developed a multiple equilibria model of migration, wherein students prefer to remain in the country where they attended university, due to a lack of information on the “value” of their degrees. So, due to signaling, good students find it more valuable to remain in the host study countries to work. In consequence, students with less “internal information”, i.e., those with lower abilities, will be those who decide to return to their countries of origin.

More recently, Rosenzweig (2006) [

6], incorporates that students are motivated by the wish to exploit the opportunity to acquire employment in the country wherein they acquired their education. Dreher and Poutvaara (2011) [

40] check the effects of staying to work in a foreign country on the decision to migrate as a student.

8 Lange (2009) [

42] focuses on the effects of the stay rates of foreign-born graduates on the rate of non-resident tuition fees, which are endogenous in his model.

In the next section, we present a theoretical model combining migration for study and for work, which stresses the alternatives choices as a function of the various costs.

3. The Model

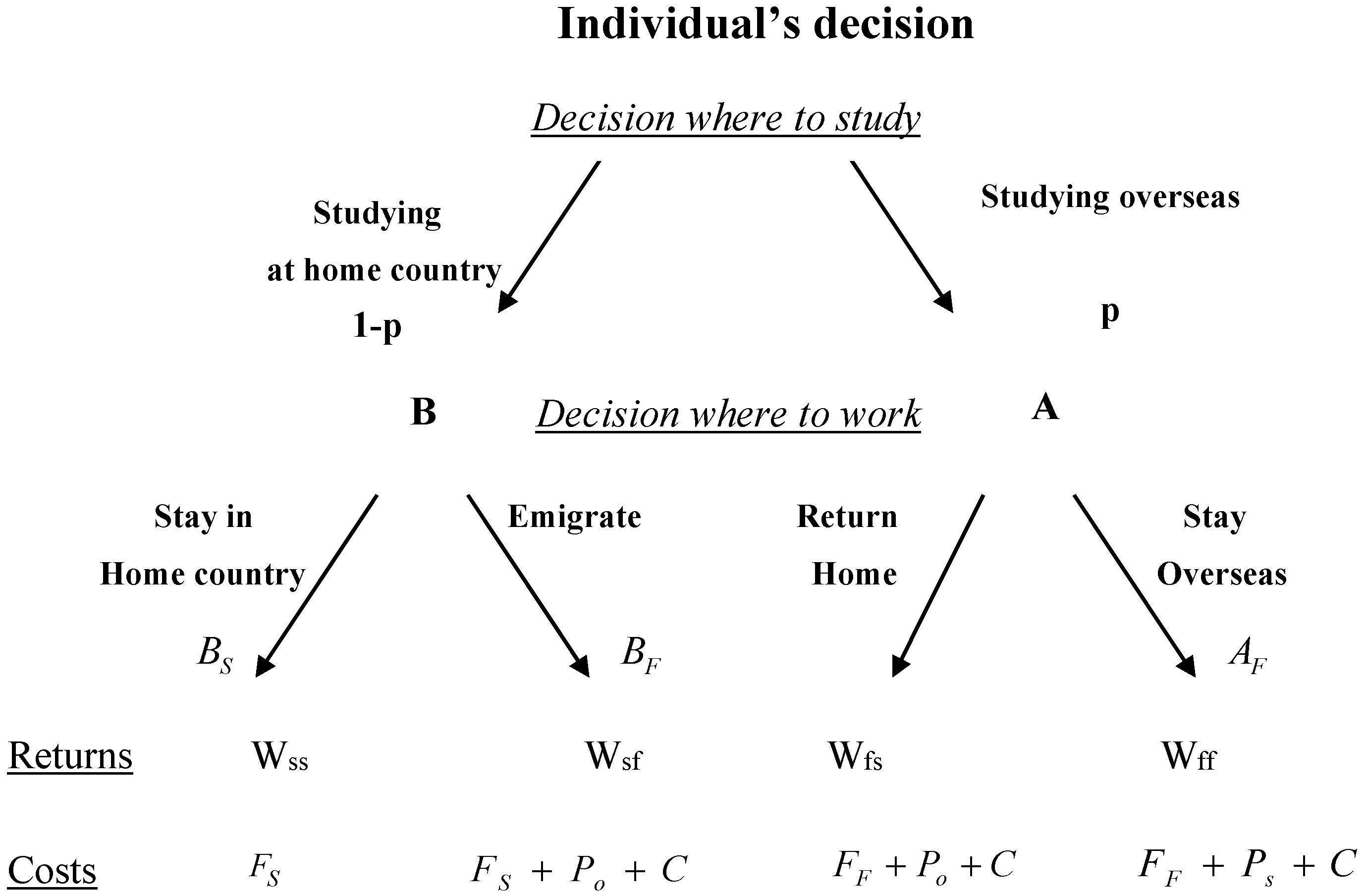

In this paper, we develop a simple cost-benefit analysis of migration decisions. The model combines the decisions related to migration of students and workers into a single model. The main idea of this ‘two-step’ model is that since the decision to work is affected by the previous decision of where to learn, it is best to analyze these two decisions in a unified model, which includes these two steps: In the first step, individuals decide where to study (i.e., in country of origin or in a foreign country); and in the second step, they decide where to work.

This unified model will allow us to analyze under which assumptions it is optimal to migrate as a student, and under which conditions it is best moving after being already educated, what is called the brain-drain strategy. We show that psychological costs are an important element affecting which one of these strategies is optimal.

Based on the literature presented above, the main assumption of this model is that the psychological costs of moving are different when young and when adult. More specifically, when psychological costs increase with age, the usual brain drain strategy is sub-optimal and therefore in countries in which young individuals can already travel for education, it is optimal to do so.

9The model we develop is the following: In the first period, individuals invest in acquiring human capital, H, and decide whether to study overseas, denoted as F, or in their home country, denoted as S. Their decision is a function of the costs and benefits from acquiring human capital. In the second period, they decide where to work. Let us start by analyzing the costs as well as the benefits of each of the decisions.

The costs mainly consist of the financial costs (including tuition fees), and psychological ones. Psychological costs are changing over time, and in consequence, will play a preponderant role in the choice of the optimal decision.

The returns are affected by two main elements: wages and quality of higher education. Wages affect net income in a direct way, while the quality of education affects the level of human capital. This paper will focus on the quality of higher education as a main element driving migration, since human capital is a function of the quality of the education students have acquired.

The model takes into account the two stages of decisions, and there are four possible strategies. In

Chart 1, we display the various strategies and variables affecting the decisions at each stage of this model.

For sake of simplicity, this basic model does not incorporate analysis of uncertainty, and we assume perfect knowledge. Moreover, the model focuses on the dichotomy of home vs. foreign country. Questions related to moving after graduation to a third country cannot be analyzed in this framework. Still, this paper allows analyzing how the equilibrium is affected by the various costs of migration. We start presenting the returns of the various strategies.

3.1. Returns from Migration

One main element which affects the future income of students is the accumulated human capital, which is a function of the quality of higher education they have acquired, as we stressed above. Students are aware that quality of higher education is heterogeneous and varies across countries; the higher the quality, the higher the human capital they are acquiring.

10 The second element which influences the future income of students are the wages per unit of human capital.

So, individual’s earning is a function of two factors: (i) the quality of higher education, which affects the accumulated human capital (where i is the index of the country in which he gets an education); (ii) the wage per unit of human capital, where j is the index of the country in which the individual decides to work (country S or country F). We assume a simple multiplicative function of both variables. We present the income of individuals in the four possible strategies:

(i) Migration as student and staying to work—strategy, .

Individuals migrate in the first stage to country F in order to obtain education and remain there after graduation.

11 The income in this

strategy is a function of

and

, and for sake of simplicity, we adopt the following functional form:

where

are the earnings of an individual who obtains education and works in country F. We assume that

is greater than zero, and

is a positive parameter. The second possible strategy is:

(ii) Temporary migration—strategy, .

Individuals migrate as students but later on return to their home country after graduation. The earnings under this strategy is a function of quality of education overseas,

and wages at home,

:

(iii) Permanent migration only as worker—strategy,

The third possible strategy is that an individual will acquire education in his home country and migrate in order to work, following graduation. This is the usual “brain drain” strategy. The value of earnings under this strategy is a function of quality of education at home,

and wages overseas,

:

(iv) No migration—strategy, .

Under this strategy, an individual acquires education in his home country and remains to work there following graduation. The present value of earnings under this strategy is:

3.2. Costs of Migration

The literature on migration stresses two main types of costs that individual bears during migration: financial costs and psychological costs.

(i) Financial Costs

As emphasized in

Section 2.2, the literature describes migration costs, as affected by distance, and language, and we denote it C. We also add tuition fees to the financial costs of migration. If the individual obtains education in his home country, the amount of tuition fees that he pays are

and if he obtains education overseas, he pays tuition fees which are charged in the host country,

.

(ii) Psychological costs

The literature presented above in

Section 2.1 has emphasized that these psychological costs are larger for adults than for young individuals at age of acquiring education. Therefore, in this paper, we assume that there are two different costs, one borne by adults migrating,

, and one by students, which are smaller and coined,

.

In summary, the net incomes under each of the strategies are as follows:

3.3. Optimization

An individual decides whether to migrate for education purpose or later on as a skilled worker, according to the net returns under each of these four strategies. This paper analyzes whether it is preferable moving while young or, alternatively, moving while already educated. From a comparison of the net returns under each of the strategies, we get the following propositions.

Proposition 1. When comparing migration for work () to migration for study (), we get that when condition I holds, it is optimal to migrate for study, while when condition I does not hold, it is optimal to migrate for work—i.e., the brain drain strategy

Condition 1. .

Proof. Under which condition do we get that ?

If: which is Condition 1, then, we get that .

The implication of Proposition 1 is that when we allow for migration of students, and do not restrain ourselves to the question of migration as adults, then we get that when differences in tuition fees are not very big, or when psychological costs of acculturation and adaptation are higher when adults, the strategy of brain drain is sub-optimal. In other words, it is optimal to move as a student.

Moreover, whenever the quality of higher education is higher overseas (such that Condition 1 holds), then migrating for study, AF, is optimal and is a better solution than the usual brain drain.

In other words, the “usual” brain drain strategy, BF, is optimal for individuals from poor countries who cannot afford learning abroad, and for whom tuition fees abroad are too high, or for whom getting visas is quite difficult. They move when they have saved enough to travel to the developed world. However, when the difference in tuition fees is not big, and obtaining a student visa is not too hard, then an individual belonging to a country with low quality of education will prefer to emigrate from his country.

This two-step model is especially important for countries in the border of the developed world, from where students can easily travel to learn. This model shows that they will move when they are still young. For them, the strategy BF is sub-optimal.

This model encompasses the idea that in the past, when learning overseas was not as easy as today, brain drain was more frequent. In the future, we might face a configuration in which young people with secondary education will leave the country to learn overseas, and will not come back, unless their “previous identity” and family ties are essential elements of their wellbeing.

In this paper, we are comparing the strategy of migrating for study vs. migrating for work. However, there is also the strategy that people will not move at all. In fact, this is still the largest share of the population. The next proposition underlines the condition under which the strategy of staying home, BS, is optimal.

Proposition 2. Under Condition 2, the strategy of staying home, is optimal.

Condition 2. and .

Proposition 2 applies to developed countries in which salaries and quality of education is high. Condition 2 is quite restraining and can be interpreted in the following way: citizen from rich countries with universities of high quality will not move to poor countries with low wages.

We should also analyze the case of countries quite similar, as the countries in the EU which due to the Bologna Process has made the system of education more similar, and in which tuition costs are almost equal for all, so that we can assume that

; we also assume that these countries have similar cultures so that psychological costs are almost nil.

12 In this case, the question is where to will students move. Will it be to countries with high wages, or to countries with high quality of education?

We get the following proposition.

Proposition 3. As a consequence of the Bologna Process, migration of students from European countries will flow into countries with the highest quality of higher education.

Proof. Due to the Bologna process, we assume few assumptions:

(a) ; (b) ; (c) and C = 0.

To prove the proposition, we need to show that if then and if then . We have two cases:

1.

If then it is easy to show that under Assumptions (a), (b) and (c) we get and therefore .

If then so that .

2.

If then it is easy to show that under Assumptions (a), (b) and (c) we get and therefore so that .

If then so that .

This proposition emphasizes that the main element, which determines whether to migrate and where to migrate to, is the quality of higher education. The reason for this effect is quite intuitive: When comparing the different net returns, it is easy to show that whatever the relative wages, the final decision to stay home or to learn abroad is a function of the quality of education. It is so, because the effect of quality of higher education is affecting the level of human capital.

This last proposition emphasizes that it is quality of higher education which is the main element conducive of migration and not the level of wages. We turn now to the empirical analysis of the last proposition, checking whether there will be concentration of students in countries with high quality of education or countries with high wages.

4. Empirical Regularities

The purpose of this exercise is to check where to are students migrating. We use a panel data of bilateral students’ flow published by the OECD on the years 2001–2006. The sample includes 29 countries: The countries from the EU 27 (without Croatia), adding Switzerland and Norway.

Besides the data on the migration flows of students, we check the wages and quality of education of these countries. Wages are the monthly average wage in manufacturing based on the ILO database.

Our quality of education index defines the quality of higher education in a country according to the number of universities in this country which are ranked among the world’s top 100 universities. Therefore, the quality of a country is higher when it has more universities which are ranked in the top 100.

There are two main ranking of universities in the world—the THE and the ARWU (Shanghai ranking). We have chosen to use the ARWU ranking since it uses criteria of research quality, research productivity, quality of the faculty, and quality of teaching. Some previous works (McMahon, 1992 [

43]; Mak and Moncur, 2001 [

31]) use instead the expenditure on education, but OECD research has shown that the correlation between budgets and quality is weak.

The first result we get is that countries with high-quality education are not necessarily those with high wages. Indeed, in

Table 1, we present the correlation between wages and quality of higher education. We find that the correlation between wages in manufacturing in each country and its number of universities in the world’s top-100, top-200, and top-500 universities is around 0.35. Therefore, the countries with the highest quality of education are not necessarily the countries with highest wages. This could be explained by more flexibility in the labor market, which is a positive element for students who just graduated and are without experience.

In

Table 2 and

Table 3, we present the distribution of student flows according to quality of higher education (in

Table 3), and according to wages (in

Table 3).

Table 2 shows that some 67 percent of student flows are concentrated in the top five countries ranked by quality of higher education.

13 Are these flows also concentrated in the top five countries ranked by wages?

In

Table 3, we measure concentration of students in countries with the highest wages. We show that more than 80 percent of the student flows went to the low wages countries. Therefore, we do not find a concentration of students in high wages countries (unlike the concentration of students in high quality countries).

These results seem to corroborate Proposition 3: movements of young individuals are towards a small number of countries, and we get a concentration effect. Our three propositions underline the importance of quality of universities in the decision-making of individuals of where to migrate.

5. Conclusions and Policy Remarks

Over these past decades, globalization has led to a huge increase in migration of workers as well as students. The aim of this paper is to answer the following question: Why will some individuals migrate to a foreign country before acquiring education, while others will migrate to work after graduating?

In order to examine the optimal strategy for the individual, we develop a “unified model’ that merges the decision to migrate as a student with the decision to migrate as a worker. This unified model allows us to analyze under which assumptions it is optimal to move as a student, and under which conditions it is optimal to go abroad after having completed one’s education, or what is referred to as the ‘brain-drain’ phenomenon.

This paper shows that when the psychological costs of migration are higher after graduating than before acquiring education, it is optimal to migrate before acquiring education. The empirical literature developed in the field of psychology appears to corroborate that, indeed, psychological costs of migration are higher the older the migrant.

Therefore, the first result of this paper is that the ‘brain drain’ strategy is optimal for individuals from poor countries who cannot afford studying abroad, since tuition fees abroad are too high. They move when they have saved enough to travel to the developed world. However, when the difference in tuition fees is not large, then an individual from a country with low-quality education will choose to migrate before having acquired education in his home country.

Our model encompasses the idea that in the past, when study overseas was not as easy as it is today, brain drain was more common. In the future, we might face a structure in which young people with secondary education will leave their home countries to study abroad, and will not return home, unless they are not allowed to stay in the host country, or unless their “home culture” and family ties are essential to their wellbeing.

A second issue is related to the impact of quality of education. This paper shows that when the costs of relocation are low, we observe an influx of students to countries with high-quality education. This result is linked to the issue of increasing global competition on talents. In the past, the elite of most countries were educated in their own countries. Today, an element common to many elites is their education, as many of them attended the same elite universities, outside their home countries. In consequence, the issue of social mobility has become linked to the international movement of students.

Nobel Prize Laureate Robert Lucas put forward a famous query in the title of his paper: “Why doesn’t capital flow from rich to poor countries?” Paraphrasing Lucas, we could state that human capital does not flow from poor to rich countries, but rather from countries with low-quality education to those with high-quality education.

In conclusion, this paper has shown that migration of students must become a subject of research no less important than that of migration of workers concerning the issues of social mobility and economic growth.