1. Introduction

Financial stress refers to disruptions in the normal functioning of financial systems, often manifesting as currency crises, banking crises, and sovereign debt crises. It is typically characterized by increased uncertainty, heightened risk aversion, and significant anticipated financial losses. During such periods, the capacity of financial institutions to function effectively is impaired (

Balakrishnan et al., 2011;

Hakkio & Keeton, 2009;

Nasir et al., 2025). To monitor and mitigate the risks of financial stress, policymakers increasingly rely on Financial Stress Indices (FSIs), which synthesize multiple market indicators into a single measure of systemic strain (

Illing & Liu, 2003,

2006;

Qureshi et al., 2024). These indices incorporate information from various sectors, including equity, bond, and money markets, as well as financial intermediaries, using key variables such as stock market volatility, sovereign bond spreads, and the Exchange Market Pressure Index (EMPI) (

Holló, 2012;

Iftikhar et al., 2024;

Misina & Tkacz, 2009;

Shah et al., 2019). In this work (

Kliesen et al., 2012), it is emphasized that FSIs in developing economies should also account for trade credit due to structural differences from advanced markets.

The reviewed literature on financial stress highlights its emergence through instability in financial systems triggered by increased risk aversion, uncertainty, and expected losses. Researchers have developed Financial Stress Indices (FSIs) to monitor these disruptions. This framework was adapted to better match the needs and conditions of emerging markets, where the underlying causes of financial stress often differ from those in advanced economies. Therefore, the study by (

Balakrishnan et al., 2011) made a significant contribution by empirically identifying the main sources of stress in these contexts, emphasizing the strong influence of financial contagion from developed countries. For Pakistan, a key significant benchmark is the study of (

Cardarelli et al., 2009), which introduced one of the first attempts to construct an FSI for Pakistan. However, their study concludes before a series of unprecedented global events that have significantly altered the economic environment, namely the COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in supply chain disruptions and major geopolitical tensions. As a result, a significant gap remains in the existing literature: no thoroughly tested financial stress index for Pakistan that covers this recent period of turmoil. This study addresses this gap by developing an updated FSI covering the years 2005 to 2024, then performing a series of robust external validity checks to test reliability, and using the validated index to identify distinct patterns of financial stress in Pakistan, distinguishing between slowly building domestic vulnerabilities and the impact of sudden external market shocks.

In this study (

Illing & Liu, 2006;

Kliesen et al., 2012), the role of FSIs in tracking systemic risk across financial markets, including equity, bond, money markets, foreign exchange, and banking institutions, is underscored, as further emphasized by (

Holló, 2012). Refs. (

Balakrishnan et al., 2011;

Iftikhar et al., 2025;

Oet et al., 2012) tailored these indices for emerging markets by incorporating indicators such as exchange market pressure, sovereign bond spreads, and stock return volatility. Recent studies employ diverse methodologies, including composite indices (

Iftikhar et al., 2025;

Lo Duca & Peltonen, 2011;

Rey, 2009) and principal component or factor models (

Hanschel & Monnin, 2005;

Tarin, 2013), with evidence suggesting that FSIs are effective early warning tools (

Cardarelli et al., 2009;

Khan et al., 2025;

Melvin & Taylor, 2009;

Vermeulen et al., 2015).

For instance, (

Shahabadi et al., 2024) employ the Markov–Switching Bayesian VAR (MSBVAR) methodology to analyze the effect of financial stress on macroeconomic variables in Iran, demonstrating the value of nonlinear models in capturing regime changes during periods of instability. In the study by (

Bu et al., 2023), a specialized stress index was developed to measure risks associated with the FinTech sector. The authors employ the MS-VAR methodology, demonstrating how macroeconomic factors can influence these emerging FinTech risks and emphasizing a modern challenge to financial stability. A study by (

Mubarak, 2025) developed FSI for Morocco, utilizing the MS-VAR (2,1) model to analyze the impact of grain prices and import bill volatility. The study identifies distinct volatility regimes, illustrating how external shocks can weaken the financial system.

Other investigations explore the effects of geopolitical shocks on inflation and currency values (

Iachini & Nobili, 2016;

K. D. Ilesanmi & Tewari, 2020;

Sadia et al., 2019) and examine how financial stress differentially impacts growth in advanced and developing economies (

Huotari, 2015). In this work (

Cevik et al., 2016;

Gonzales et al., 2024;

Shah et al., 2020;

Tajammal & Butt, 2025;

Valerio Roncagliolo & Villamonte Blas, 2022), it is further noted that higher financial integration in developed economies increases their susceptibility to global financial shocks compared with emerging economies.

History of Financial Stability in Pakistan

The development of a Financial Stability Index (FSI) for Pakistan must be based on the country’s frequent episodes of financial distress, which highlight the need for a systematic tool to monitor systemic risk. Pakistan’s financial system has experienced repeated stresses caused by both domestic vulnerabilities and external shocks. During the 1990s, the banking sector faced a persistent crisis characterized by a rise in non-performing loans, weak institutional governance, and inadequate regulatory oversight. These structural weaknesses led to extensive reforms, including the large-scale privatization of state-owned banks and a strengthened supervisory role for the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) (

Husain, 2003).

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis further exposed the country’s macro-financial fragility. Although Pakistan’s banks were less exposed to toxic assets, the crisis triggered a rapid depletion of foreign exchange reserves, sharp currency depreciation, and severe balance of payments pressures, culminating in an IMF stabilization program (

Haq & Bukhari, 2020;

International Monetary Fund, 2009). In the following years, periodic episodes of currency instability, widening current account deficits, and external debt vulnerabilities have required repeated IMF involvement, emphasizing the persistent structural imbalances in the economy (

International Monetary Fund, 2018). These well-documented episodes of banking fragility, exchange market pressures, and sovereign risk form the empirical foundation for constructing a comprehensive FSI. They reveal that financial stress in Pakistan arises from both domestic structural weaknesses and global shocks, making a composite index crucial for monitoring systemic vulnerabilities and supporting timely policy responses (

Iftikhar et al., 2025;

Tariq & Shafique, forthcoming). In constructing an FSI for Pakistan, several components are integrated to reflect the country’s macroeconomic and financial environment. The banking sector’s risk is assessed through changes in real deposits, domestic private sector claims, and foreign liabilities. Stock market volatility, a key stress indicator, is estimated using the GARCH(1,1) model (

Cipollini & Mikaliunaite, 2020;

Ghosh et al., 2024), which is consistent with established approaches (

Cardarelli et al., 2011;

Cevik et al., 2013). Exchange market pressure is measured using the EMPI methodology (

Bollerslev, 1986;

Ishrakieh et al., 2020;

Malega, 2016), as supported by previous studies (

Bussiere & Fratzscher, 2006;

Garibaldi et al., 2001;

Girton & Roper, 1977;

Iftikhar et al., 2024), which captures movements in exchange rates and reserves. Sovereign bond risk is assessed through the yield spread between Pakistan Investment Bonds and U.S. Treasury securities (

Abdullah et al., 2017;

Batool, n.d.;

Cevik et al., 2013). External debt risk is quantified based on its growth rate (

G. L. Kaminsky, 1997;

Kruger et al., 1998). Due to data limitations, trade finance is proxied by net financial flows (

Abiad, 2003;

Sachs et al., 1996). The growth in the private sector is evaluated in terms of credit stress claims (

Bell & Jones, 2015;

Cevik et al., 2016;

Kenc et al., 2021). Liquidity stress in the money market is reflected through bid–ask spreads, which utilize the highest and lowest prices when direct data are unavailable (

Aizenman et al., 2012;

Kaiser, 1974;

G. L. Kaminsky, 1997;

Shah et al., 2022). Stock market illiquidity is also measured using bid–ask spreads derived from monthly high and low prices (

Hakkio & Keeton, 2009;

Iftikhar et al., 2023;

Koyunlu, 2000;

Stolbov & Shchepeleva, 2016). These indicators collectively form a comprehensive financial stress index tailored to Pakistan’s economic and financial conditions.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the data sources and methodology used to construct the Financial Stress Index (FSI), including the rationale for indicator selection and the implementation of Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Section 3 reports and interprets the empirical findings, highlighting the identification of major stress periods and the relationship between financial stress and macroeconomic performance. This section also includes a set of robustness checks by comparing the FSI with established global indicators such as the U.S. STLFSI4, Global Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU), Geopolitical Risk (GPR), and the OECD Composite Leading Indicator (CLI). Finally,

Section 4 offers policy implications based on the results and suggests avenues for future research, particularly in enhancing the index’s alignment with high-frequency global financial signals.

3. Results

The results of the PCA are presented in

Table 5, which shows the proportion and eigenvalues of the six PCs, depicted within the sub-indices of the market segments. Moreover, PCA is computed on the standardized dataset, where PC1 accounts for 41.4% of the total variance in our data, with an eigenvalue of 2.45, which is greater than 1.

Figure 1’s scree plot is based on PCA and shows that the first three components have eigenvalues greater than one, together explaining about 82.3% of the total variation in the data. According to the Kaiser Criterion, components with eigenvalues above one are considered useful for the analysis. Therefore, PC1 accounts for 40.7% of the variance, making it the most significant of all the other components. The third component in the plot exhibits a noticeable drop in eigenvalues, suggesting that the remaining components contribute very little to the variance explanation. Therefore, based on the results, the FSI was constructed using the first principal component (PC1).

Table 6 characterizes the PC1 results, along with their eigenvectors or weights, for the individual stress indicators of submarket indices. The variable weights illustrate the degree of financial stress in Pakistan, which is mainly determined by the banking sector’s riskiness. The same result is also found in Malaysia (

Abiad, 2003), Russia, and Bulgaria (

Bollerslev, 1986). The positive variables in

Table 6 display a one-standard-deviation change in the corresponding market segments from the final FSI. The negative sign indicates that both dimensions are inversely proportional to one another; if one dimension increases, the other dimension decreases subsequently. The results in

Table 6 indicate that in severe financial stress, the banking sector risk exhibits the highest PCA weight, confirming its leading role in contributing to economic stress in Pakistan. To illustrate the proxies, the index highlights the actual foreign liabilities of banks, total deposits, and claims in the domestic private sector. Thus, the weights of the variable indicate that uncertainty in the banking sector typically drives the degree of financial stress. Furthermore, during periods of excessive financial stress, the banking system of Pakistan became weakened; similarly, the results were obtained by (

G. L. Kaminsky, 1997) for Russia and Bulgaria and (

Abiad, 2003) for Malaysia.

Moreover, in

Table 6, EMPI, which serves as a proxy for currency risk, is very low, indicating that currency depreciation typically occurs due to stress accumulating in further financial markets. Thus, it can be suggested that the weight of EMPI contributes to increased financial stress in Pakistan. Furthermore, it is known that the rise in the FSI of advanced economies may cause a currency crisis in developing markets by improving their EMPI; however, it is also noted that the surge in financial stress in developed countries cannot affect their EMPI, while the EMPI in developing economies becomes low. Therefore, the likelihood of growing financial stress in advanced economies increases the risk of a currency crisis in Pakistan, suggesting that EMPI contributes positively to financial stress. Similar results were found in studies by (

Abiad, 2003;

Kruger et al., 1998). The negative weight of SMV in the PCA-based FSI could be due to several factors. Firstly, in developed economies, heightened stock market volatility often signals financial instability. However, in emerging markets such as Pakistan, increased volatility does not necessarily indicate distress but can be linked to heightened trading activity and liquidity fluctuations. If stock market volatility positively correlates with liquidity rather than financial distress, PCA may assign it a negative weight to maintain statistical balance (

Dewald & Schreck, 2023).

Additionally, PCA constructs components to maximize variance while ensuring orthogonality between factors. If SMV trends differently from other key financial stress indicators, such as credit risk or interest rate spreads, PCA may allocate it a negative weight to balance the overall variance. Another factor could be that, in some emerging markets, greater stock volatility coincides with speculative foreign capital inflows, which do not necessarily indicate worsening financial conditions (

Adhikari, 2023). The methodological approach also plays a role in standardizing data for PCA. When variables with high variance and asymmetric distributions, such as stock market volatility, are included, the resulting weights may appear counterintuitive due to normalization effects. Thus, the negative weighting of SMV does not imply that stock market volatility reduces financial stress; rather, it reflects the unique market conditions in Pakistan, where capital flows, liquidity dynamics, and statistical transformations influence PCA results.

Pakistan’s financial system is largely bank-driven, with the banking sector holding approximately 75% of total financial assets, unlike developed economies that have more diversified financial structures. This heavy reliance on banking institutions increases systemic risk, especially during economic downturns. The underdevelopment of capital markets compels firms and investors to primarily utilize banking channels, thereby intensifying financial vulnerabilities during periods of monetary tightening and external shocks (

Adhikari, 2023;

Gadanecz & Jayaram, 2008;

Kentikelenis & Stubbs, 2024). Therefore, our study found a positive relationship between external debt in Pakistan. Furthermore, it can be stated that financial stress is a result of an increase in external debt. During periods of extreme financial stress, external liabilities in Pakistan are likely to increase over time.

Furthermore, our finding that external debt is positively correlated with financial stress supports (

Fisunoğlu & Akyüz, 2025), who argue that extreme external borrowing in developing economies often leads to financial instability. Therefore, following the study by (

Fisunoğlu & Akyüz, 2025), external debt is recognized as a primary driver of financial vulnerability. The observed negative weight of SMV in the FSI could be linked to capital reallocation effects or monetary policy mechanisms. During periods of heightened stock market fluctuations, investors may redirect funds to the banking sector, thereby reducing perceived financial instability (

Chakrabarty & Shkilko, 2013). This dynamic may explain the counterintuitive result observed in the analysis, although it differs from findings in prior studies such as (

Chakrabarty & Shkilko, 2013;

Fisunoğlu & Akyüz, 2025).

According to the Asian Development Bank (

Aboura & Van Roye, 2017), despite the moderate improvements, Pakistan’s stock market has developed at a slower pace compared with its regional counterparts. Market capitalization as a percentage of GDP stands at around 15%, significantly lower than India’s 50% or Malaysia’s 80%. This limited stock market penetration constrains financial diversification and increases economic dependence on the banking sector liquidity. The slow expansion of the capital markets may explain why SMV has a counterintuitive negative weight in the FSI, as the banking sector’s resilience mitigates financial stress during times of stock market fluctuations. Additionally, the FSI trends align closely with periods of economic distress, notably the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2018 currency depreciation crisis. These periods saw significant spikes in financial stress, characterized by capital outflows, increased credit spreads, and sharp interest rate adjustments by the IMF (

Reinhart et al., 2012). Given the high dependence on external financing, financial instability in Pakistan tends to be driven more by external shocks and policy responses rather than purely stock market dynamics. These empirical understandings reinforce the argument that financial stress in Pakistan is closely linked to the stability of the banking sector and external economic conditions, rather than stock market fluctuations alone. Therefore, future financial policy should focus on deepening capital markets and enhancing financial diversification to reduce systemic risks.

The money market spread (MMS) represents the short-term cost of borrowing money, which can lead to liquidity risk. According to this study (

Thomas, 2009), the MMS reduces bank lending, which in turn decreases financial activities. In contrast,

Kose et al. (

2009) note that an increase in MMS has a positive impact on financial stress. Therefore, it is stated that a rise in MMS contributes positively to financial stress; a similar result was found in our study (see

Table 6). In connection with external debt, the rise in external debt also mitigates financial stress, suggesting that market participants have less interest in debt sustainability. According to

Bollerslev (

1986), the quickest development in external debt is considered uncertain; at the same time, the association between external debt and financial stress is considered vague. The PCA eigenvector for the external debt component of our study (see

Table 6) contradicts the results of

Bollerslev (

1986) and

G. L. Kaminsky (

1997), who concluded that short-term external debt is adversely affecting FSI in Russia, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Poland. However, this study found a positive association between external debt in Pakistan. It can be mentioned that financial stress rises as a result of an upsurge in external debt, and during excessive financial stress, external liabilities in Pakistan will grow over time. Hence, following the results of the study by

Abiad (

2003) and

Fisunoğlu and Akyüz (

2025), who mentioned in their study that external debt is one part that slows down the economy’s growth, financial stress rises as a result of an increase in external debt.

The last row of

Table 6 indicates that trade finance has a negative contribution to Pakistan’s financial stress. A similar result was found for Malaysia (

Abiad, 2003) and (

G. L. Kaminsky, 1997), as well as for Turkey, Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic. The results align with our expectations, as

Bollerslev (

1986) suggests that financial flows play a significant role in the economic growth of emerging economies. Likewise,

Yu et al. (

2021) mentioned that capital flow has a positive impact on external trade. Considering this,

Walsh (

2022) concludes that an increase in trade finance ultimately decreases financial stress.

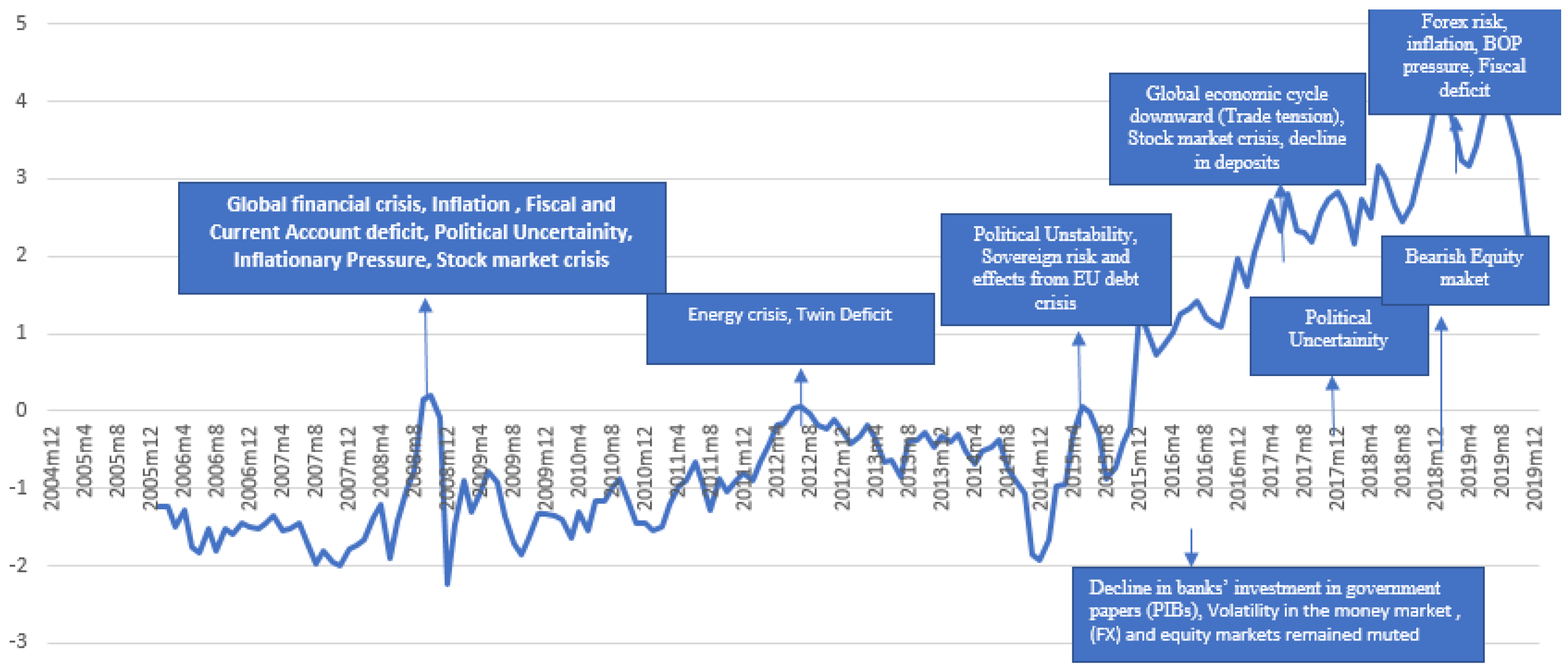

Figure 2 represents the FSI for Pakistan. According to the plot of FSI for Pakistan in

Figure 2, which shows the monthly behavior. The six standardized components are summarized to produce the aggregate FSI for Pakistan. As shown in

Figure 2, the Financial Stress Index (FSI) highlights multiple periods of heightened stress in Pakistan’s financial system. A sharp rise in financial stress can be observed in late 2007 and early 2008, aligning closely with the intense political instability and turmoil following the assassination of former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto (

Rahman et al., 2018). The first notable surge occurred during 2008–2009, following the collapse of Lehman Brothers. According to the Financial Stability Review (FSR), 2008 was marked as one of the most disruptive years in recent financial history, driven by global market turmoil and rising commodity prices. Pakistan was affected both directly and indirectly through reduced trade activity and capital flight. The second event indicates ongoing inflationary pressures. Although temporary balance of payments (BOP) surpluses initially reduced currency risk, the use of external debt rather than sustainable investment weakened financial stability, with moderate stress emerging by 2012 due to the twin deficit issue. The third episode, occurring between 2015 and 2016, was linked to lower export demand from Europe amid the Eurozone debt crisis, which partially offset the benefits of falling oil prices. The fourth significant stress period arose in 2017 due to political uncertainty and volatility in equity markets. Global investors withdrew around 40% of their investments from the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) amid increasing risks, including financial regulation changes, regional conflicts, and cyber threats. In 2017–2018, the fifth spike reflected rising macroeconomic imbalances, including sustained pressure on foreign exchange reserves and a sharp depreciation of the rupee. However, the sixth peak in 2018–2019 was marked by persistent currency weakness, despite a narrowing current account deficit. Finally, the seventh surge in early 2019 was triggered by geopolitical tensions with India, which briefly disrupted investor confidence and business sentiment. These stress episodes demonstrate the FSI’s effectiveness in capturing both domestic and external financial shocks. Furthermore, to analyze the contribution of various financial and economic components to financial stress more intensively, the financial stress component is plotted in

Figure 2.

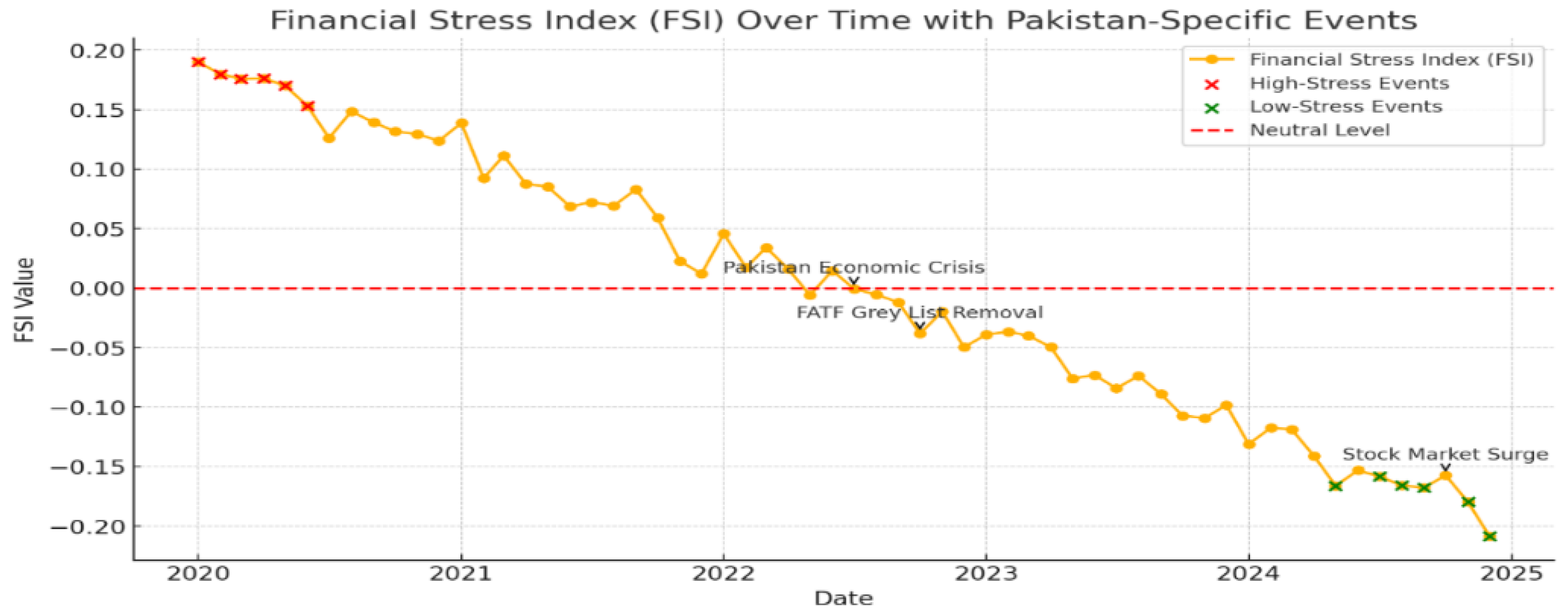

According to

Figure 3, FSI testing provides a quantitative assessment of financial volatility in Pakistan, highlighting the relationship between financial stress levels and macroeconomic events.

Figure 3 reflects the onset of a difficult period starting in July 2022. Although the economy was under considerable stress, as evident from declining foreign exchange reserves, high inflation, and a depreciating currency, the FSI displayed a declining trend. This unexpected drop in financial stress is primarily attributed to the strong positive market reaction to Pakistan’s removal from the FATF grey list in October 2022, which appears to have offset the impact of broader macroeconomic challenges during that time. Additionally, in October 2024, the KSE 100 experienced a significant surge, indicating a decline in financial stress and reflecting the capital market’s resilience and strengthened investor sentiment. Furthermore, the SBP decision in March 2025 maintained the interest rate at 12% rather than implementing expected rate cuts, which may have introduced financial stress and volatility due to the uncertainties surrounding the direction of monetary policy. Hence, these findings highlight the significance of financial regulations, foreign investment, and economic policy in shaping financial stress movements, offering critical insights for financial analysts, policymakers, and researchers to focus on macroeconomic stability in developing markets (

Dugbartey, 2025).

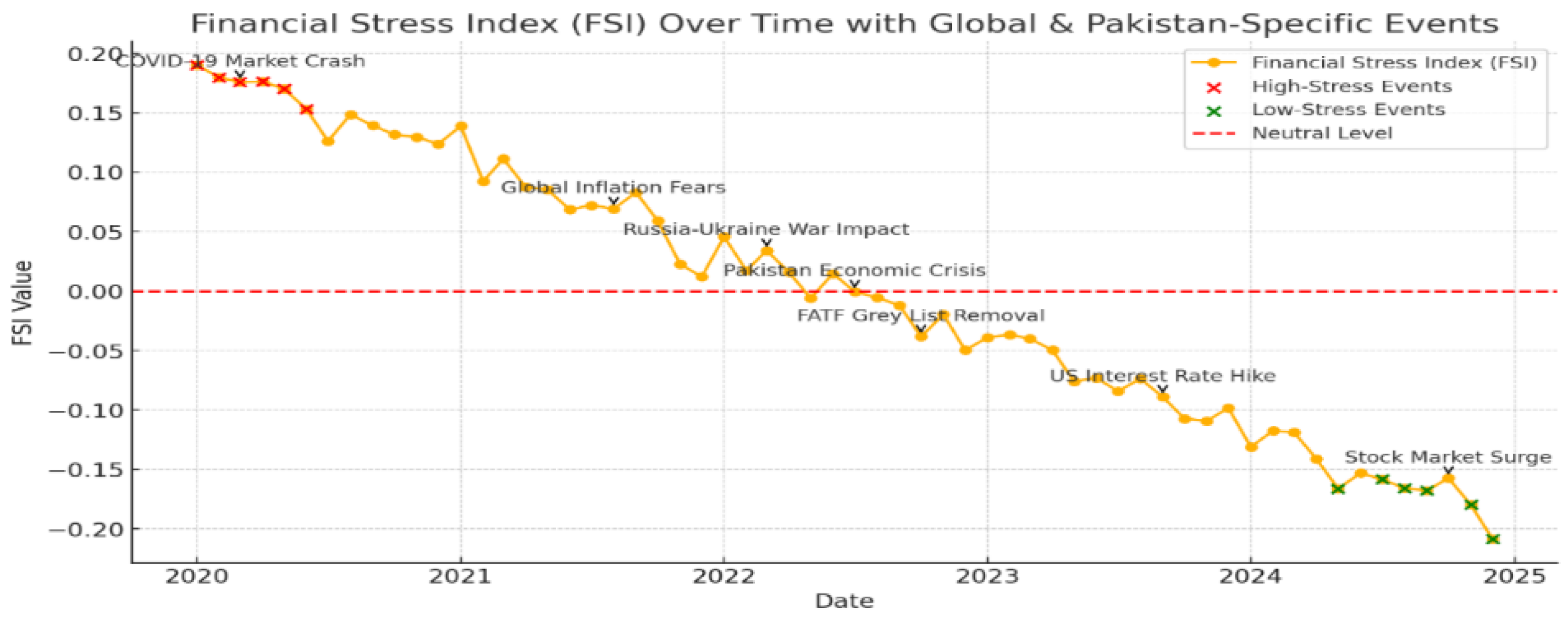

Figure 4 FSI demonstrates the significant influence of global economic events on financial volatility. The first phase was identified as the COVID-19 market downturn in March 2020, which led to a sharp spike in financial stress, as clearly visible in

Figure 4 around the event labeled

COVID market crash. This initial shock was followed by a period of recovery as economies began to reopen (

Smil, 2005). As economies progressively reopened, inflationary pressure emerged in August 2021, further exacerbating financial stress driven by supply chain limitations, rising consumer prices, and adjustments in the central bank’s monetary policy, as noted by Walsh (

Dunaway, 2009). Furthermore, in March 2022, the Russia–Ukraine war led to additional financial instability, significantly impacting the global energy market, increasing geopolitical risk, and causing fluctuations in international stock and trade markets. Additionally, the U.S. Federal Reserve’s interest rate hike in September 2023 created economic pressure, particularly in developing markets, where capital outflow, a depreciated currency, and tighter liquidity conditions exacerbated financial stress (

Pohlner, 2016). According to (

Ijaz et al., 2019), these trends highlight the interconnectivity of global financial systems and underscore the need for robust strategic risk management and economic policy frameworks to mitigate the adverse effects of international financial disturbances.

Table 7 highlights key periods of financial stress in Pakistan, identified through structural break analysis and supported by major macroeconomic events. These breakpoints reflect phases of economic instability driven by both domestic and global developments. The analysis covers the period from 2005 to 2019, showing that the FSI experienced significant shifts in response to various economic shocks. The first major breakpoint appeared in June 2005, aligning with a surge in global oil prices that heightened uncertainty for energy-dependent economies. A second shift in July 2005 concurred with Pakistan’s trade policy reforms, potentially altering market dynamics and contributing to financial stress (

Goyal, 2014).

Furthermore, another major breakpoint emerged in December 2015, likely influenced by China’s economic slowdown and a steep drop in oil prices, affecting both oil-exporting and importing countries (

Abbass et al., 2022). These international factors contributed to increased financial volatility. Moreover, in 2019, further structural shifts were detected amid Pakistan’s economic challenges, including IMF bailout negotiations, rising inflation, currency depreciation, and fiscal tightening. Breakpoints in July and November of that year align with the IMF loan agreement and subsequent reforms, underscoring the critical role of financial policy changes in shaping market stress (

Thaher et al., 2022). Overall, these findings reflect the strong interplay between external shocks such as oil price fluctuations and global recessions and domestic economic decisions in influencing financial stability (

Corsi, 2022).

According to

Table 8, the July 2019 event corresponds to IMF Country Report No. 19/212 (July 2020), in which Pakistan secured a

$6 billion Extended Fund Facility. This marked a pivotal shift in the country’s economic strategy, requiring the government to float the exchange rate, enforce fiscal discipline, and reduce imbalances. These measures triggered immediate changes in monetary indicators, notably in exchange rate dynamics and inflation levels. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 led to severe global and domestic economic disruptions. In Pakistan, it severely impacted local industries, investor confidence, and foreign trade. Additionally, the lockdown and growing uncertainty led to a significant decline in the economy’s GDP, a severe deterioration in the stock market, and increased unemployment (

Gayathri et al., 2024). The post-COVID-19 economic recovery began in mid-2021, supported by global vaccine distribution. However, stability was short-lived as the Russia–Ukraine war erupted in early 2022, reigniting global uncertainty. This conflict drove commodity prices higher and disrupted supply chains, renewing inflationary and fiscal pressures (

Neumann, 2023). Further instability emerged in April 2022 when Prime Minister Imran Khan was ousted, intensifying political uncertainty. Inflation surged, and by July 2022, the Pakistani rupee had depreciated sharply, signaling deep macroeconomic imbalances (

Saliminezhad & Bahramian, 2021). By January 2023, foreign exchange reserves had plunged below

$3 billion, raising fears of default and highlighting vulnerabilities in the external sector (

Gupta et al., 2022). As cited by (

Kasal, 2023), the general elections convened in February 2024 led to a political change that resulted in constancy or lack thereof, which likely had a significant impact on the behavior of investors outside the country and its economic course of action moving forward.

In

Table 9, the first null hypothesis of FSI does not Granger cause industrial production (IPG) with a

p-value of 0.4551% with a 10% significance level, as it was rejected, and our result is similar to

Bollerslev (

1986);

Kruger et al. (

1998), but it contradicts the study of

G. L. Kaminsky (

1997). The authors report that financial stress has a significant impact on the IPG in Southeast Asian countries like South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines. Industrial production is one of the heavily subsidized sectors in Pakistan. It can be argued that one of the reasons behind the insignificant causal relationship between financial stress and industrial production is government support; hence, industrial production reacts independently of overall financial stress in the economy. However, in contrast to some Southeast Asian economies, the IP in Pakistan appears to be less responsive to changes in financial stress levels, likely due to the continued government support. This insulation may enable the sector to continue functioning even when the broader economy is under financial stress, as noted by

Muguto et al. (

2022).

Moreover, during the study periods such as 2008, 2012, and 2015–2018, financial stress was high, but the energy sector was not affected due to subsidies received from the government: Rs 97 million in 2007, Rs 37,266 million in 2010–2011, and in 2017–2018 the subsidiary received Rs 314,614 million. Therefore, it is argued that industrial production and FSI demonstrate a weak relationship owing to the number of subsidies administered by the respective governments during the study period. Secondly, the Granger causality relationship exists between FSI and FTG at a 0.001% probability value, and the results are significant at a 5% level of significance. This finding proposes that instabilities in financial stress levels have a measurable impact on the performance of FTG. Similar results have been observed in previous studies by

Kruger et al. (

1998) and

Bollerslev (

1986). According to

Dahalan et al. (

2016), foreign trade plays an essential role in shaping a country’s economic output, as it contributes directly to the GDP through the exchange of services and goods across borders. Likewise, a significant relationship is found between the FSI and GDPG, with the F-statistic value at a 0.000% probability value firmly rejecting the null hypothesis. Since this is the only study to have shown a significant relationship between FSI and GDPG. Additionally, the impact of government debt on economic growth is not consistent; it varies depending on the level of debt and the current state of financial markets. When financial stress intensifies or public debt surpasses a specific threshold, its negative impact on economic growth becomes more pronounced (

Muguto et al., 2022). Lastly, a Granger causality relationship exists between FSI and FCFG at a 0.038% probability value, which is accepted at a 5% significance level, similar to the findings made by

Kruger et al. (

1998) and

Bollerslev (

1986). Hence, the outcome suggests that there is an essential relationship between financial stress and economic activity. Therefore, the F-statistic in

Table 8 demonstrates the computation of economic activity such as FTG, GDPG, and FCFG, which expect IPG to fail to Granger-cause the FSI at standard 5% and 10% significance levels. The dynamic relationships between financial stress and economic performance may not be well captured by a conventional linear Granger causality paradigm, as our study acknowledges, given the structural changes observed around 2020, particularly due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated worldwide disruptions. Using a sample-splitting strategy, we divided the entire sample into two periods: pre-2020 (2005–2019) and post-2020 (2020–2024) to overcome this limitation. The Granger causality tests are re-estimated for every sub-sample. The findings, presented in

Table 10 and

Table 11, reveal directional correlations that were obscured in the full-sample analysis (

Table 9) but are now more evident and statistically significant. These findings offer a more sophisticated view of causality under various economic regimes, which is compatible with the existence of structural breaks.

3.1. Relationship and Measurement of Economic Activity Variables

In the study by

Gupta et al. (

2022), decision-making plays a significant role in the economic outlook and the prices of financial assets, as financial stress is a key factor in the economic recession, leading the country to reduce most of its expenses. Likewise, the reduction of government expenditure also hinders the growth of several industries nationwide. However, a transmission channel exists between economic activity and financial stress, which should be highlighted by the country’s regulatory authorities and policymakers. It has also been stated in the study by

Muguto et al. (

2022) that the financial accelerator and real options are the two financial channels linking economic activity to financial stress. According to a study conducted by

Dewald and Schreck (

2023), financial stress has a significant influence on a country’s economic activities. However, the relationship between the two is considered to have a negative impact, as a surge in financial stress results in a decrease in the country’s economic activities. Moreover,

Muguto et al. (

2022) stated that the influence of financial stress on economic activities is vital to understanding the scope of the financial cycle. Primarily, we provide support based on the results of Granger causality between FSI and measures of economic indicators; the results are reported in

Table 7. In this section, we have examined the vital relationship between FSI and economic indicators individually. Therefore, we provide IRF from the unrestricted bivariate VARs technique through Cholesky’s decomposition, where we order the FSI shock initially. Our measure of economic indicators is the 12-month growth rate of four economic activity variables named industrial production growth (IPG), growth of foreign trade (FTG), gross domestic product growth (GDPG), and fixed capital formation growth (FCFG) in Pakistan. The data are sourced from the State Bank of Pakistan and FRED, covering the period from 2005 to 2019.

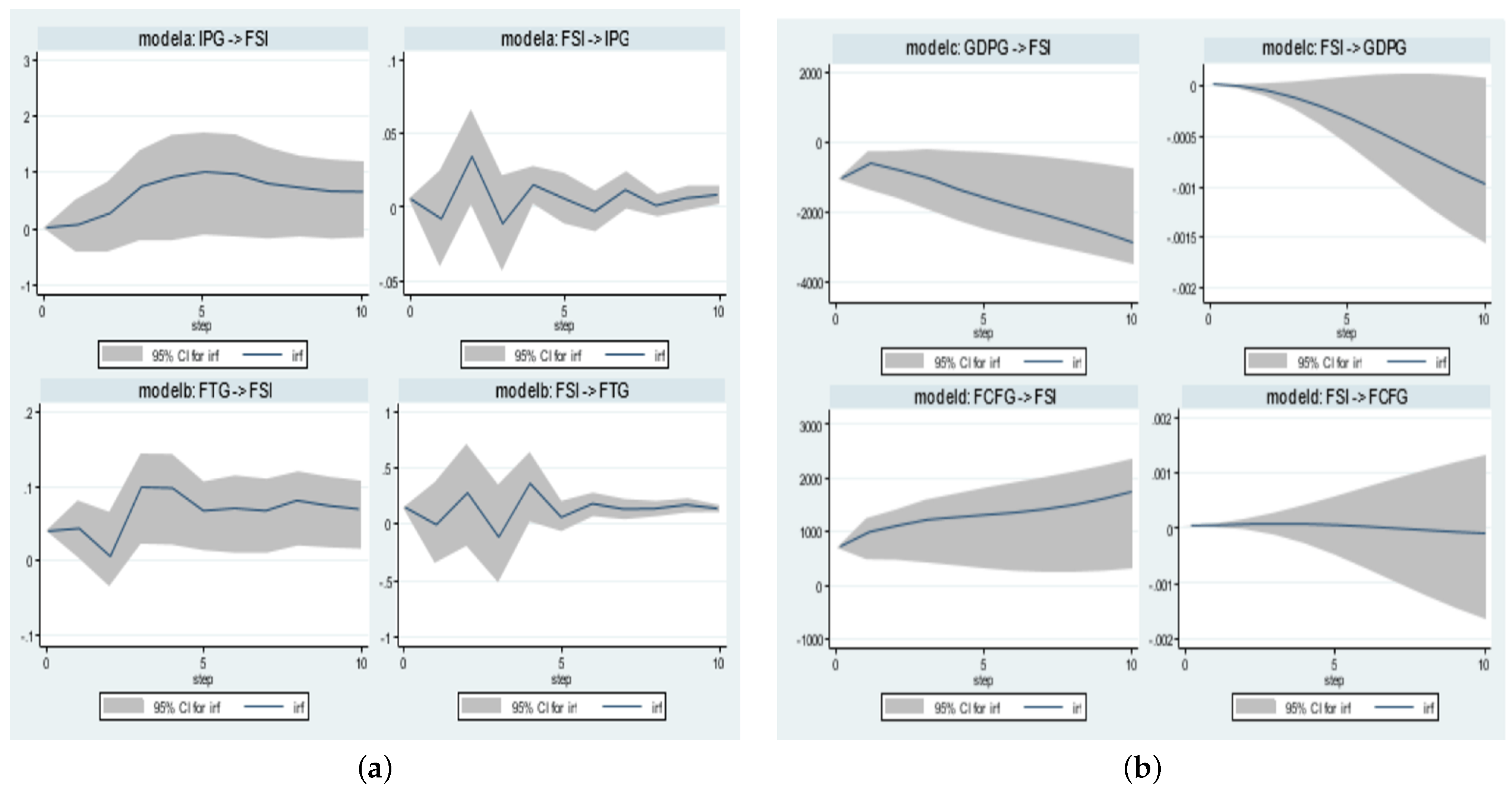

Figure 5a,b exhibit the IRF, in which column

Figure 5a depicts the response of the economic activity to the FSI, whereas column

Figure 5b depicts the impulse function of the FSI towards economic activity.

Figure 5 illustrates that shocks to the Financial Stress Index (FSI) have no discernible effect on Industrial Production Growth (IPG). FSI, on the other hand, responds volatily to changes in IPG and only becomes meaningful at the tenth lag over time. At the first lag, Financial Tightness Growth (FTG) reacts to FSI

Figure 5a shocks in a robust and positive manner; however, at the second lag, it becomes volatile and negative. Shocks from FSI have a substantial detrimental effect on GDP Growth (GDPG), with a downward trend from the second to the tenth lag. On the other hand, FSI’s reaction to GDPG is negligible at first but becomes important over time. From the first to the tenth lag, Foreign Capital Flow Growth (FCFG) responds consistently, positively, and meaningfully to FSI shocks. In contrast, FSI is unaffected by FCFG shocks and remains constant and negligible during this time. This implies that although financial stress affects macroeconomic factors such as

Figure 5b FTG, GDPG, and FCFG, it has little effect on IPG. On the other hand, FTG and GDPG have noticeable but delayed effects on financial stress, exposing unequal economic dynamics in Pakistan. Finally, it is also observed that the confidence bands expand over longer time horizons, reflecting increased uncertainty in the long-term estimates of the impulse responses (IR).

3.2. External Validity and Robustness Checks

This section evaluates the robustness and external validity of our newly constructed index by performing external comparisons against established global indicators. A critical test for any Financial Stress Index (FSI) in an emerging market is its relationship with financial conditions in major global economies. Following the approach of important studies such as

Park and Mercado (

2014), we contrast the Pakistan FSI with the U.S. St. Louis Fed Financial Stress Index (STLFSI4) (

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2024).

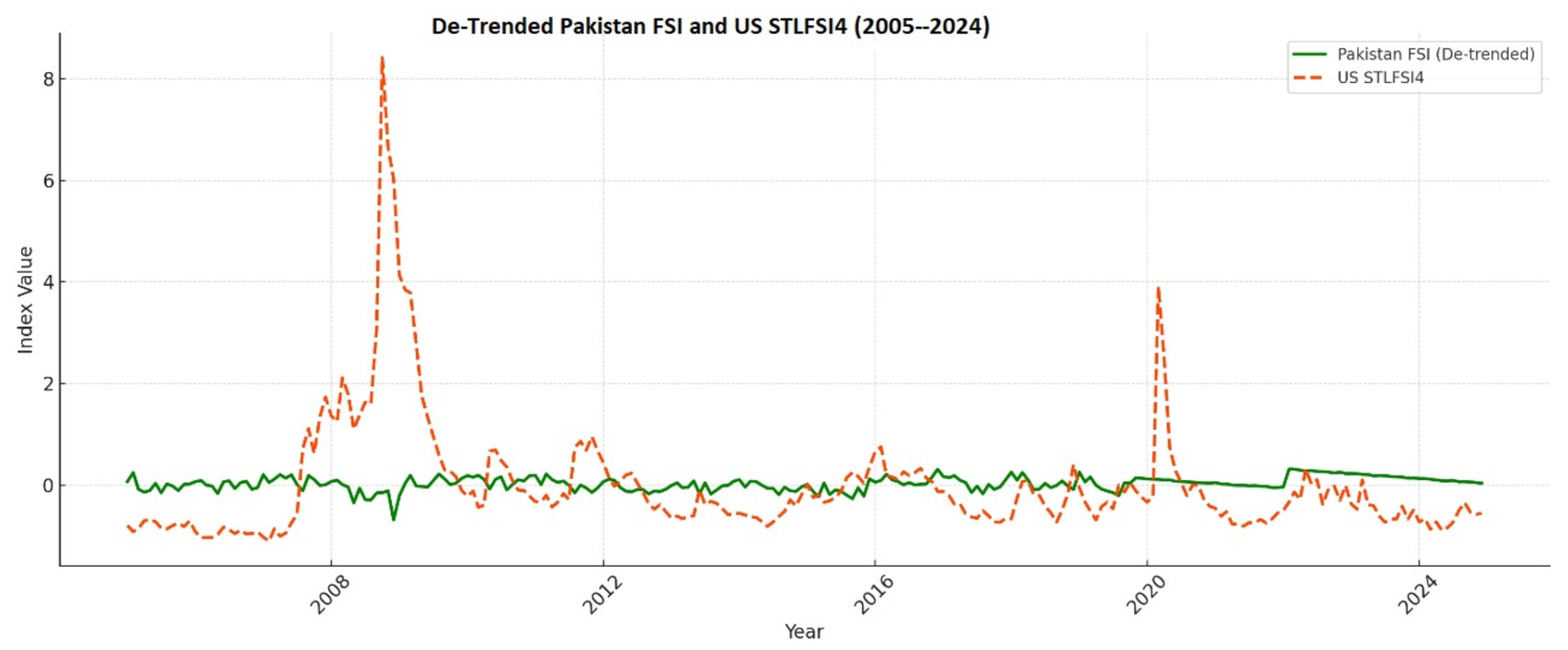

Figure 6 provides a graphical comparison of the two detrended indices. The overall correlation coefficient for the corresponding period from 2005 to 2024 is

. Although this negative correlation may appear counterintuitive, it reflects the contrasting structural design and functional objectives of the two indices. The STLFSI4, constructed from high-frequency, market-based indicators, is designed to capture sudden financial market turmoil, especially within advanced economies (

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2024). Conversely, the Pakistan FSI relies on more gradually evolving macro-financial metrics—such as bank deposits, domestic credit growth, and sovereign risk—making it better suited for identifying systemic vulnerabilities rather than reacting to rapid global market contagion. Unlike the STLFSI4, which responds swiftly to global financial market fluctuations, the Pakistan FSI reflects stress derived from structural indicators, including banking sector fragility, exchange market pressure, stock market volatility, money market spreads, external debt exposure, and trade finance conditions. This enables it to capture systemic risks rooted in the domestic macroeconomic and financial environment. These divergent characteristics are evident during two major global events. In 2008, when the global financial crisis originated in the U.S. banking system, the STLFSI4 surged abruptly, while Pakistan’s FSI remained largely stable, suggesting limited immediate contagion into the domestic system. However, in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic—a crisis that affected countries worldwide and disrupted daily economic activities—both indices showed similar upward movements, indicating that Pakistan’s FSI is capable of capturing widespread financial stress when driven by universal and globally transmitted shocks. Therefore, despite the modest negative correlation, the index remains a valuable tool for assessing domestic financial stress and fulfilling its core function of highlighting macroprudential vulnerabilities in Pakistan. Nonetheless, the index could be further strengthened by integrating volatile market-based indicators to better align with global stress patterns and support more robust international benchmarking.

To further validate the external consistency of our de-trended FSI for Pakistan, we examine its correlation with two widely recognized measures of global risk: the

Global Economic Policy Uncertainty (GEPU) Index (

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2023) and the

Geopolitical Risk (GPR) Index (

George, 2023). As shown in

Table 12, the findings show that the Pakistan FSI exhibits a positive correlation of +0.40 with GEPU and +0.36 with the GPR. These moderate and statistically meaningful relationships indicate that periods of heightened global uncertainty and geopolitical instability are generally associated with increased financial stress in Pakistan. This strengthens the external validity of our index and supports its capacity to capture stress spillovers from global economic and political developments. The result aligns with theoretical expectations and prior empirical literature, increasing confidence in the index as a robust tool for macro-financial monitoring in an open economy context.

Moreover,

Table 12 also presents the correlation between the Pakistan FSI and the

OECD Composite Leading Indicator (CLI), a proxy for global business cycle expectations (

Caldara & Iacoviello, 2022). The correlation is +0.107, indicating a weak positive relationship. This counterintuitive result—where an improving global economic outlook is linked to a slight rise in financial stress—can be explained by Pakistan’s specific vulnerabilities as a commodity-importing emerging economy. While a global boom may increase demand for Pakistani exports, it also tends to elevate global commodity prices, particularly oil. For a net importer like Pakistan, this results in a higher import bill, a worsening current account deficit, and downward pressure on the currency, all of which contribute to domestic financial stress (

Caldara & Iacoviello, 2022). Thus, the weak positive correlation suggests that our FSI correctly captures how the negative effects of rising commodity prices during global expansions may offset the benefits of improved export performance. This validates the index as a nuanced measure of Pakistan’s unique macro-financial exposure (

Rathore et al., 2023).