Interest Rates and Economic Growth: Evidence from Southeast Asia Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Theoretical Foundations of Interest Rates and Economic Growth

2.1.2. Deposit Interest Rates and Economic Growth

2.1.3. Loan Interest Rates and Economic Growth

2.1.4. Combined Impact of Deposit and Loan Interest Rates on GDP Growth

2.2. Research Hypothesis

2.2.1. Deposit Rates and GDP Growth

2.2.2. Loan Rates and GDP Growth

3. Research Data and Methodology

3.1. Data Description

3.2. Panel ARDL Model

4. Research Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Stationary Test

4.4. Cointegration Test

4.5. Optimal Lags

4.6. Panel ARDL Regression Results

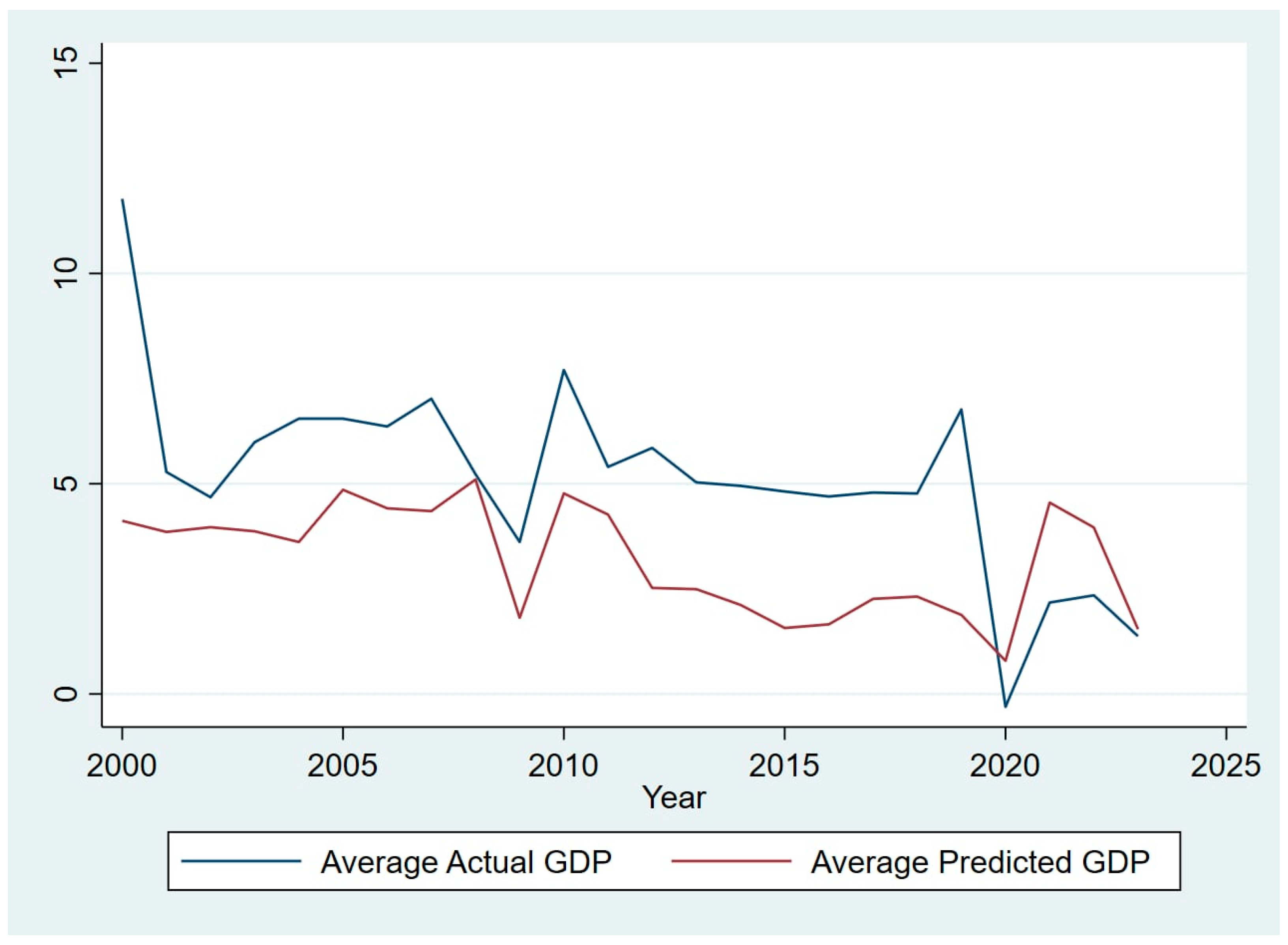

4.7. Forecast of GDP Fluctuation Trends for Southeast Asia

4.8. Limitations and Future Research Agenda

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aghion, P., Bacchetta, P., & Banerjee, A. (2001). Currency crises and monetary policy in an economy with credit constraints. European Economic Review, 45(7), 1121–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASEAN Secretariat. (2023). ASEAN matters: Epicentrum of growth. Available online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/FIN_ASEAN-Annual-Report-2023-June-December-Epub-1.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Asian Development Bank. (2023). Asian development outlook 2023. Available online: https://www.adb.org/publications/asian-development-outlook-2023 (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M., & Kanitpong, T. (2017). Do exchange rate changes have symmetric or asymmetric effects on the trade balances of Asian countries? Applied Economics, 49(46), 4668–4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank Indonesia. (2023). Monthly pociy review. Available online: https://www.bi.go.id/en/publikasi/laporan/Pages/TKM-Desember-2023.aspx (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Barnett, W. A., & Sergi, B. S. (2023). Macroeconomic risk and growth in the Southeast Asian countries: Insight from SEA. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernanke, B. S., & Gertler, M. (1995). Inside the black box: The credit channel of monetary policy transmission. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(4), 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, O., Rhee, C., & Summers, L. (1993). The stock market, profit, and investment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(1), 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, I. (1930). The theory of interest. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Gali, J. (2015). Monetary policy, inflation, and the business cycle: An introduction to the new Keynesian framework and its applications (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. S., Voumik, L. C., Ahmed, T. T., Alam, M. B., & Tasmim, Z. (2024). Impact of geopolitical risk, GDP, inflation, interest rate, and trade openness on foreign direct investment: Evidence from five Southeast Asian countries. Regional Sustainability, 5(4), 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huu, T. N. (2023). Adaptive management approaches in ASEAN economies: Navigating inflation, unemployment, and economic growth dynamics. Revista Gestão & Tecnologia, 23(4), 396–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest and money. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R. (1997). Financial development and economic growth: Views and agenda. Journal of Economic Literature, 35(2), 688–726. [Google Scholar]

- Mishkin, F. S. (1995). Symposium on the monetary transmission mechanism. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(4), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C. V. (2025). The role of economic integration policies in increasing economic growth in selected Southeast Asian countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. H., Van Nguyen, B., Nguyen, T. T., & Luu, D. H. (2024). Productivity unleashed: An ARDL model analysis of innovation and globalization effects. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(8), 5694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obstfeld, M., & Rogoff, K. (1996). Foundations of international macroeconomics. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pappas, A., & Boukas, N. (2025). Examining impact of inflation and inflation volatility on economic growth: Evidence from European union economies. Economies, 13(2), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. P. (1999). Pooled Mean Group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94(446), 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, B., Zhu, Q., & Khan, M. I. (2019). Real interest rate and economic growth: A statistical exploration for transitory economies. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 534, 122193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. B. (1993). Discretion versus policy rules in practice. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 39, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vithessonthi, C. (2023). The consequences of bank loan growth: Evidence from Asia. International Review of Economics & Finance, 83, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2024). World development report 2024: The middle-income trap. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2024 (accessed on 1 August 2024).

| Variables | Meaning | Calculation | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||

| GDP | GDP Growth Rate: Represents the rate of change in the economic output of a country over time. This rate enables the measurement of economic expansion. | The growth rate of GDP emerges from dividing the difference between current and preceding GDP values by the preceding GDP figure then multiplying by 100. Typically, GDP growth rate is calculated as | World Bank, International Financial Statistics (IFS) |

| Independent variables | |||

| DIR | Deposit Interest Rate: Represents the payment which banks provide to their depositors, the expense of saving, or depositing money to banks. | Annual percentage rates (APRs) define the interest payments which banks offer to deposit account holders. | Central Banks, International Financial Statistics (IFS) |

| LIR | Lending Interest Rate: The interest rate charged by banks on loans or credit extended to business entities and individuals. | The annual interest rate charged by financial institutions for lending funds to borrowers, expressed as an APR. | Central Banks, International Financial Statistics (IFS) |

| Control variable | |||

| CPI | Consumer Price Index: A measure of inflation, reflecting modifications in costs of typical household consumption through changes in the standard prices of product assortment. | The price of a specific selection of goods and services from a particular year is compared to their base year value to generate the measurement. | World Bank, Central Banks, International Financial Statistics (IFS) |

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | 5.1422 | 5.9474 | −20.5842 | 58.0781 |

| DIR | 3.6270 | 3.3841 | 0.1217 | 15.5025 |

| LIR | 9.8936 | 5.6103 | 3.0600 | 32.0000 |

| CPI | 5.2963 | 8.2206 | −21.7393 | 59.0838 |

| GDP | DIR | LIR | CPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | 1.0000 | |||

| DIR | 0.1829 | 1.0000 | ||

| LIR | 0.2435 | 0.6507 | 1.0000 | |

| CPI | 0.1287 | 0.4071 | 0.3584 | 1.0000 |

| Variables | Inverse Chi-Squared (p-Value) | Inverse Normal (p-Value) | Inverse Logit (p-Value) | Modified Inv. Chi-Squared (p-Value) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | 134.0762 (0.0000) | −9.1782 (0.0000) | −9.6427 (0.0000) | 16.8961 (0.0000) | I(0) |

| DIR | 127.5567 (0.0000) | −9.0042 (0.0000) | −9.6427 (0.0000) | 15.9133 (0.0000) | I(0) |

| LIR | 19.8424 (0.5929) | 0.2755 (0.6093) | 0.3550 (0.6384) | 23.3952 (0.6275) | I(1) |

| CPI | 149.0322 (0.0000) | −9.5488 (0.0000) | −10.0000 (0.0000) | 19.1508 (0.0000) | I(0) |

| Statistics | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Modified Dickey–Fuller t | −6.8230 | 0.0000 |

| Dickey–Fuller t | −5.7994 | 0.0000 |

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −7.0713 | 0.0000 |

| Unadjusted modified Dickey–Fuller t | −11.0427 | 0.0000 |

| Unadjusted Dickey–Fuller t | −6.7909 | 0.0000 |

| Growth | DIR | LIR | CPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| ID2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| ID3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| ID4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| ID5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| ID6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| ID7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| ID8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| ID9 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| ID10 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| ID11 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Conclusion | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| MG | PMG | DFE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | LR | SR | LR | SR | LR | SR |

| ECT | −0.0317 *** | −0.9774 *** | −0.1568 *** | |||

| DIR | 0.6779 | 0.6808 ** | 0.2931 ** | |||

| LIR | −0.1620 ** | 0.2680 *** | −0.0772 * | |||

| CPI | 0.1727 * | −0.0998 *** | 0.0919 ** | |||

| DIR | 0.5626 ** | 4.1447 *** | 0.6156 *** | |||

| LIR | 3.8499 * | −1.3046 ** | −9.9394 ** | |||

| CPI | 0.2910 * | 3.8692 ** | 0.3782 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, T.H. Interest Rates and Economic Growth: Evidence from Southeast Asia Countries. Economies 2025, 13, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080244

Nguyen TH. Interest Rates and Economic Growth: Evidence from Southeast Asia Countries. Economies. 2025; 13(8):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080244

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Tan Huu. 2025. "Interest Rates and Economic Growth: Evidence from Southeast Asia Countries" Economies 13, no. 8: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080244

APA StyleNguyen, T. H. (2025). Interest Rates and Economic Growth: Evidence from Southeast Asia Countries. Economies, 13(8), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080244