Safeguarding Economic Growth Amid Democratic Backsliding: The Primacy of Institutions over Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Democracy, Institutions, and Economic Growth: A Review

1.2. The Global Decline in Democracy: Trends and Economic Implications

1.3. Contribution of the Study

2. Theoretical Model

2.1. A Solow-Based Model with Democracy, Innovation, and Institutions

2.1.1. Production Function

2.1.2. Labor and Capital Dynamics

2.1.3. Total Factor Productivity (TFP)

- is a baseline productivity parameter,

- denotes the level of innovation,

- represents the level of democracy (assumed constant in the baseline case),

- captures the elasticity of TFP with respect to innovation,

- reflects the direct effect of democracy on TFP through institutional quality.

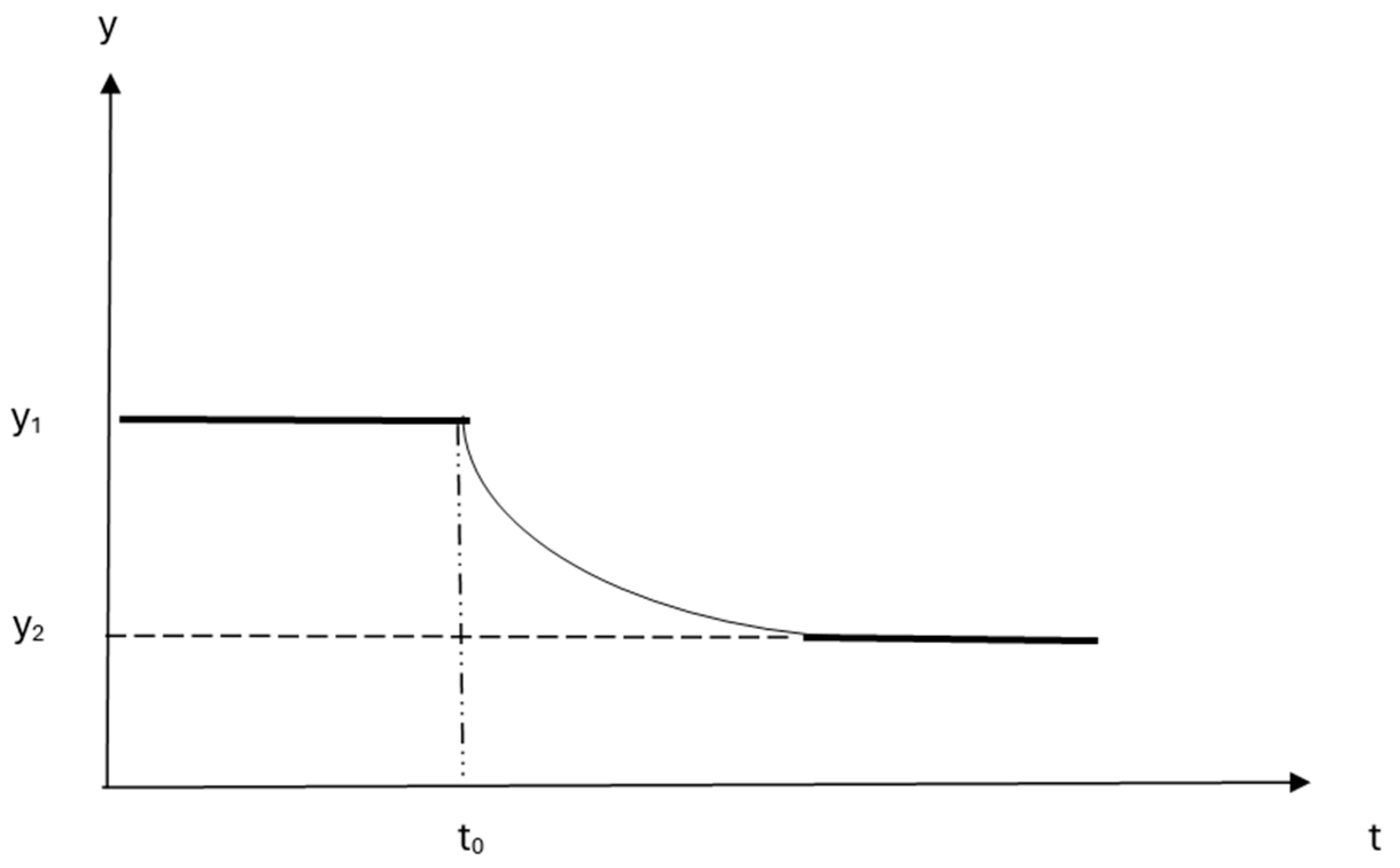

2.1.4. Steady-State Analysis

2.1.5. Interpretation

- (1)

- Innovation Channel: , where democracy enhances innovation (), which in turn boosts TFP.

- (2)

- Institutional Channel: , where democracy directly improves TFP via stronger institutions, independent of innovation.

2.2. Growth Rate in the Steady State

2.3. Comparative Statics

2.4. Statistical Methodology

3. Data Sources and Variable Descriptions

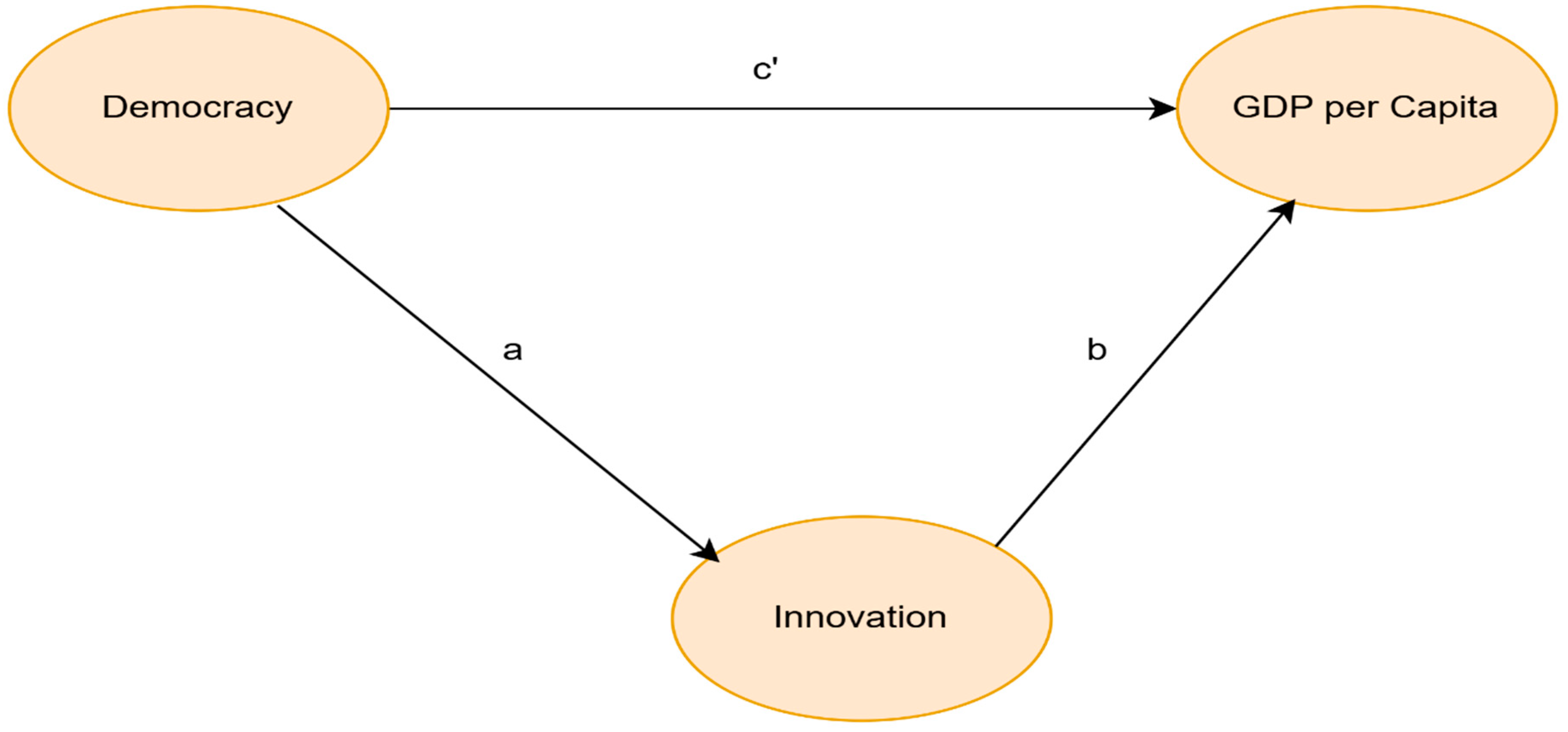

Mediation Analysis Framework

- (1)

- Effect of democracy on innovation (Path a)

- o

- Examining whether higher levels of democracy create an institutional environment conducive to innovation by fostering market competition, protecting intellectual property rights, and encouraging R&D investment.

- (2)

- Effect of innovation on GDP per capita (Path b)

- o

- Assessing whether higher levels of innovation lead to greater economic output, potentially through increased productivity, technological spillovers, and efficiency gains.

- (3)

- Total effect of democracy on GDP per capita (Path c)

- o

- Measuring the overall impact of democracy on economic growth before controlling for innovation, capturing both its direct influence and indirect pathways.

4. Fixed-Effects Mediation Analysis Results

Robustness Tests

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.2. Relevance to Today’s Political Landscape

5.3. Political Economy of Reform Sequencing

5.4. Limitations of the Study

5.5. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Albania | Honduras | Oman |

| Algeria | Hong Kong | Pakistan |

| Argentina | Hungary | Panama |

| Armenia | Iceland | Paraguay |

| Australia | India | Peru |

| Austria | Indonesia | Philippines |

| Azerbaijan | Iran | Poland |

| Bahrain | Ireland | Portugal |

| Bangladesh | Israel | Qatar |

| Belarus | Italy | Romania |

| Belgium | Jamaica | Russian Federation |

| Benin | Japan | Rwanda |

| Bolivia | Jordan | Saudi Arabia |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Kazakhstan | Senegal |

| Botswana | Kenya | Serbia |

| Brazil | Republic of Korea | Singapore |

| Bulgaria | Kuwait | Slovakia |

| Burkina Faso | Kyrgyzstan | Slovenia |

| Cambodia | Latvia | South Africa |

| Cameroon | Lebanon | Spain |

| Canada | Lithuania | Sri Lanka |

| Chile | Luxembourg | Sweden |

| China | Madagascar | Switzerland |

| Colombia | Malaysia | Tajikistan |

| Costa Rica | Mali | Thailand |

| Croatia | Malta | Togo |

| Cyprus | Mauritius | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Czech Republic | Mexico | Tunisia |

| Denmark | Moldova | Turkey |

| Dominican Republic | Mongolia | Uganda |

| Ecuador | Montenegro | Ukraine |

| Egypt | Morocco | United Arab Emirates |

| El Salvador | Mozambique | United Kingdom |

| Estonia | Namibia | United States |

| Ethiopia | Nepal | Uruguay |

| Finland | Netherlands | Uzbekistan |

| France | New Zealand | Vietnam |

| Georgia | Nicaragua | Zambia |

| Germany | Niger | Zimbabwe |

| Ghana | Nigeria | |

| Greece | North Macedonia | |

| Guatemala | Norway |

| Model | F-Statistic | p-Value | Preferred Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democracy on innovation | Fixed effects | ||

| Innovation on GDP per capita | Fixed effects | ||

| Democracy on GDP per capita | Fixed effects | ||

| Democracy and innovation on GDP per capita | Fixed effects |

| Model | Hausman Test Statistic | p-Value | Preferred Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democracy on innovation | Fixed effects | ||

| Innovation on GDP per capita | Fixed effects | ||

| Democracy on GDP per capita | Fixed effects | ||

| Democracy and innovation on GDP per capita | Fixed effects |

| Regression | F Statistic | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democracy on innovation | Significant improvement | ||

| Innovation on GDP per capita | Significant improvement | ||

| Democracy on GDP per capita | Significant improvement | ||

| Democracy and innovation on GDP per capita | Significant improvement |

Appendix B. Empirical Implementation of GMM and Diagnostic Test Results

- Panel dimensions: 123 countries × 12 years (2011–2022)

- Structure: Short time dimension (T = 12) but with a large cross-sectional component (N = 123)

- Estimation method: Two-step System GMM with lagged levels and differences as instruments

- Hansen J test of overidentifying restrictions:

- J = 1.15 × 109, df = 858, p ≈ 0.00

- Interpretation: The full set of instruments is strongly rejected, indicating invalidity of the instrument matrix due to overfitting and a singular weighting matrix.

- Serial correlation in first-differenced errors:

- AR(1): ρ = −0.057, z = −1.90, p = 0.057 (expected negative first-order autocorrelation)

- AR(2): ρ = −0.100, z = −3.15, p = 0.0016

- Interpretation: The significant AR(2) statistic indicates a violation of the moment conditions necessary for valid GMM estimation.

- Instrument proliferation inflates the number of instruments relative to the number of periods, resulting in a near-singular weighting matrix and unreliable estimates.

- The failure of the Hansen and AR (2) tests confirms that the moment conditions are violated, and the instruments are invalid.

- The estimated coefficients from the GMM model, while close in magnitude to our baseline fixed-effects models, cannot be considered statistically reliable.

- Corrects for heteroskedasticity, serial correlation, and cross-sectional dependence

- It is well-suited to short panels like ours

- Produces stable and interpretable results under weaker assumptions

| 1 | While Total Factor Productivity (TFP) is often broadly defined, its application here is specifically focused on its relationship with democracy and innovation, enhancing clarity and relevance for our study. For a detailed discussion on the nuances and differences in TFP, readers are directed to Bertsatos and Tsounis (2024). |

| 2 | Due to missing values across the panel period, our final sample included 123 countries for which complete data were available between 2011 and 2022. |

| 3 | World Bank, World Development Indicators, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators, accessed on 18 March 2025. |

| 4 | As a robustness check, we estimated a dynamic panel model using two-step System GMM, but encountered severe identification problems. For full results and interpretation, see Appendix B. |

| 5 | We also examined the Polity V (Polity 5) index for the years 2011–2018. Notably, the Polity V index shows no change (variance = 0) for 73% of countries in our sample, and only minimal variation for another 10%. This empirical invariance supports our assumption of short-term exogeneity and demonstrates why standard regression-based checks using Polity V are not feasible for our data. |

| 6 | The sum of the direct and indirect effects is 3.21 PPP dollars larger than the total effect. This minor difference is attributed to specification adjustments and interaction effects typical in fixed-effects models with panel data. |

References

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy does cause growth. Journal of Political Economy, 127(1), 47–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Business. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). The narrow corridor: States, societies, and the fate of liberty. Penguin UK. [Google Scholar]

- Aghion, P., Antonin, C., & Bunel, S. (2021). The power of creative destruction: Economic upheaval and the wealth of nations. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R. J. (1996). Democracy and growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 1(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartle, J., Birch, S., & Skirmuntt, M. (2017). The local roots of the participation gap: Inequality and voter turnout. Electoral Studies, 48, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauhr, M., & Grimes, M. (2014). Indignation or resignation: The implications of transparency for societal accountability. Governance, 27(2), 291–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsatos, G., & Tsounis, N. (2024). Differences in total factor productivity and the pattern of international trade. Economies, 12(4), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, M., & Hefeker, C. (2007). Political risk, institutions and foreign direct investment. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, J., & Howarth, D. (2025). Realigning European public financial architecture for the twenty-first century. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 28(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L. J. (2019). Ill winds: Saving democracy from Russian rage, Chinese ambition, and American complacency. Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Economist Intelligence Unit. (2023). Democracy index 2022: Frontline democracy and the battle for Ukraine. EIU. Available online: https://www.eiu.com/n/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Democracy-Index-2022_FV2.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Financial Times. (2024, June 3). Transcript: Martin Wolf on democracy’s year of peril—2024. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/ea46aab9-b69f-44b2-9475-67e89d013677 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Freedom House. (2024). Freedom in the world 2024: The global expansion of authoritarian rule. Freedom House. Available online: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2022/global-expansion-authoritarian-rule (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Grzymala-Busse, A., Kuo, D., Fukuyama, F., & McFaul, M. (2020). Global populisms and their challenges (Global Populisms Cluster). Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Haggard, S., & Kaufman, R. R. (2016). Dictators and democrats: Masses, elites, and regime change. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haggard, S., & Tiede, L. (2011). The rule of law and economic growth: Where are we? World Development, 39(5), 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2020). Education, knowledge capital, and economic growth. In S. Bradley, & C. Green (Eds.), The economics of education (2nd ed., pp. 171–182). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, R. (2013). Does trust promote growth? Journal of Comparative Economics, 41(3), 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isham, J., Kaufmann, D., & Pritchett, L. H. (1997). Civil liberties, democracy, and the performance of government projects. The World Bank Economic Review, 11(2), 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin Yi, D. (2012). No taxation, no democracy? Taxation, income inequality, and democracy. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 15(2), 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2011). The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, 3(2), 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1999). The quality of government. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 15(1), 222–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). How democracies die. Crown Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Mounk, Y. (2018). The people vs. democracy: Why our freedom is in danger and how to save it. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olken, B. A. (2007). Monitoring corruption: Evidence from a field experiment in Indonesia. Journal of Political Economy, 115(2), 200–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. (1999). Where did all the growth go? External shocks, social conflict, and growth collapses. Journal of Economic Growth, 4(4), 385–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. (2000). Institutions for high-quality growth: What they are and how to acquire them. Studies in Comparative International Development, 35(3), 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., Dhir, S., Das, V. M., & Sharma, A. (2024). Analyzing institutional factors influencing the national innovation system. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R., & Tang, S.-J. (2018). Democracy’s unique advantage in promoting economic growth: Quantitative evidence for a new institutional theory. Kyklos, 71, 642–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, J., & Wacziarg, R. (2001). How democracy affects growth. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1261–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economist. (2023, February 15). Israel’s proposed legal reforms are a dreadful answer to a real problem. Available online: https://www.economist.com/leaders/2023/02/15/israels-proposed-legal-reforms-are-a-dreadful-answer-to-a-real-problem (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Touchton, M. (2016). Campaigning for capital: Fair elections and foreign investment in comparative perspective. International Interactions, 42(2), 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadlamannati, K. C., & Tamazian, A. (2009). Growth effects of FDI in 80 developing economies: The role of policy reforms and institutional constraints. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 12(4), 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V-Dem Institute. (2024). Democracy report 2024: Democracy winning and losing at the ballot. University of Gothenburg. [Google Scholar]

- Wampler, B., & Hartz-Karp, J. (2012). Participatory budgeting: Diffusion and outcomes across the world. Journal of Deliberative Democracy, 8(2), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (n.d.). Democracy index (EIU). Last modified 2024. Available online: https://prosperitydata360.worldbank.org/en/indicator/EIU+DI+INDEX (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). (n.d.). Global innovation index 2024. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/global_innovation_index/en/ (accessed on 18 March 2025).

| Variable | Definition | Unit of Measurement | Data Source | Years | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Democracy Index (EIU) | A score reflecting the level of democratization in a country, including civil and political rights. | Score (Scale: 0–10) | EIU/World Bank | 2011–2022 | Reflects multidimensional democratic quality across elections, governance, participation, political culture, and civil liberties. |

| The Global Innovation Index (GII) | The index measures an economy’s innovation ability using 80 indicators across seven pillars. | Score (Scale: 0–100) | World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)/World Bank | 2011–2022 | GII data, from diverse sources, enables consistent cross-country innovation comparisons |

| GDP per capita in purchasing power parity (PPP) | Adjusts economic output per person for international price differences, enabling accurate living standard comparisons | US Dollars | World Bank, World Development Indicators (WDI) | 2011–2022 | Serves as the primary measure of economic performance. |

| Variable | Model 1 | SE 1 | Model 2 | SE 2 | Model 3 | SE 3 | Model 4 | SE 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democracy | 0.45 * | (0.26) | 1466.55 *** | (489.51) | 1224.89 ** | (489.30) | ||

| Innovation | 544.13 *** | (148.69) | 533.91 *** | (149.13) | ||||

| R2 Within | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.31 | ||||

| F-Statistic | 566.49 | 327.56 | 315.77 | 362.02 | ||||

| N | 1476 | 1476 | 1476 | 1476 |

| EIU Democracy Index Dimension | Economic Rationale | Key References |

|---|---|---|

| Strengthening Electoral Processes and Pluralism | Builds public and investor trust, lowers political risk, and supports higher investment and long-term growth | Touchton (2016); Acemoglu and Robinson (2019) |

| Improving the Functioning of the Government | Fosters efficient allocation of public resources and enhances fiscal credibility | Kaufmann et al. (2011); Olken (2007) |

| Enhancing Political Participation | Improves policy quality and growth, reallocates spending to human capital, and strengthens cohesion and labor-force participation | Wampler and Hartz-Karp (2012); Bartle et al. (2017) |

| Strengthening Political Culture | Fuels trust-driven growth, reduces risk, supports innovation, and strengthens national innovation systems | Horváth (2013); Bauhr and Grimes (2014); Singh et al. (2024) |

| Safeguarding Civil Liberties | Fosters innovation and R&D, attracts FDI, and improves public investment outcomes through enhanced transparency and rights protection | Acemoglu et al. (2019); La Porta et al. (1999); Isham et al. (1997); Busse and Hefeker (2007) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ben Malka, R.; Hadad, S. Safeguarding Economic Growth Amid Democratic Backsliding: The Primacy of Institutions over Innovation. Economies 2025, 13, 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080237

Ben Malka R, Hadad S. Safeguarding Economic Growth Amid Democratic Backsliding: The Primacy of Institutions over Innovation. Economies. 2025; 13(8):237. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080237

Chicago/Turabian StyleBen Malka, Ran, and Sharon Hadad. 2025. "Safeguarding Economic Growth Amid Democratic Backsliding: The Primacy of Institutions over Innovation" Economies 13, no. 8: 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080237

APA StyleBen Malka, R., & Hadad, S. (2025). Safeguarding Economic Growth Amid Democratic Backsliding: The Primacy of Institutions over Innovation. Economies, 13(8), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080237