1. Introduction

Climate change, particularly the accelerating greenhouse effect, is a global environmental concern that is a result of both human-related and natural causes. Therefore, the need to protect the environment continues to be a world priority (

J. Wang et al., 2024;

World Bank, 2025). As such, the effect of trade openness on the environment is a significant issue in international trade policies and agreements among trading blocs. The empirical and theoretical literature on the trade–environment nexus is riddled with mixed results and suggestions.

J. Sun (

2024) noted that the interconnectedness and interdependence of global economies continue to increase, and international trade has increased to a new level. There is a continued shift in the production of goods to China, which are then exported to emerging and developing African economies. Notably,

J. Sun (

2024) further suggested that a large number of Chinese industrial firms also move their operations to African countries, among which are Southern African Customs Union (SACU) members.

Founded in 1910, the SACU is one of the oldest customs unions in the world and has evolved from a colonial-era setup to a more democratic entity (

Gibb, 2006). The customs union was at first controlled by South Africa, but it experienced significant changes with new accords in 1969 and 2002 that addressed imbalances in development and decision-making among member nations. The 2002 agreement established shared governance frameworks, including a Council of Ministers and a permanent Secretariat, as a shift from South Africa’s sole decision-making authority (

Ngalawa, 2013). The union’s basic goal is to make trade free and easy for its members and enhance trade openness. In its strategic plan for 2022–2027, the SACU admits that it is concerned with environmental quality and emphasises moving away from environmentally damaging economic activities. The plan also suggests that significant advances should occur in new industrial production methods, commodity demand, trade, and investment movements.

Also, the SACU countries face a range of environmental pollution concerns, such as air and water pollution, waste management issues, and threats to wildlife and the extinction of species. In 2023, the union’s economy grew by 5.4 percent in comparison to 6.4 percent in the year 2022 (

Southern African Customs Union, 2025). This increase indicates not only the region’s resiliency but also its prospects for long-term and sustainable growth. The mining and quarrying and manufacturing sectors are among the major drivers of economic growth in the SACU economies. However, this economic progress is closely linked to the extraction of natural resources beyond regeneration capability and potentially increases carbon emissions and deteriorates environmental quality (

T. Mosikari, 2024). Therefore, many of the SACU economies grow at a cost. According to the

Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (

2023) in South Africa, 80% of the primary energy supply comes from non-renewable energy, and coal is dominant. In light of the energy security advantage from coal,

Gava et al. (

2025) noted that it appears deceptive to assume that non-renewable energy can easily be substituted by other main energy sources without lowering economic growth. However, pollution of the environment due to mining activities has become a source of sorrow. The

Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (

2018) noted that even though there is precise execution of well-defined rehabilitation procedures, degradation from pre-mining to post-mining land capability is unavoidable. Also,

Greenpeace (

2024) stated that in South Africa, energy generation alone accounts for 23% of the fine particulate matter in the air, with particles less than 2.5 micrometres in diameter (PM2.5) being a high burden. At the national level, South Africa and Eswatini, both SACU members, have significant coal-related PM2.5 emissions.

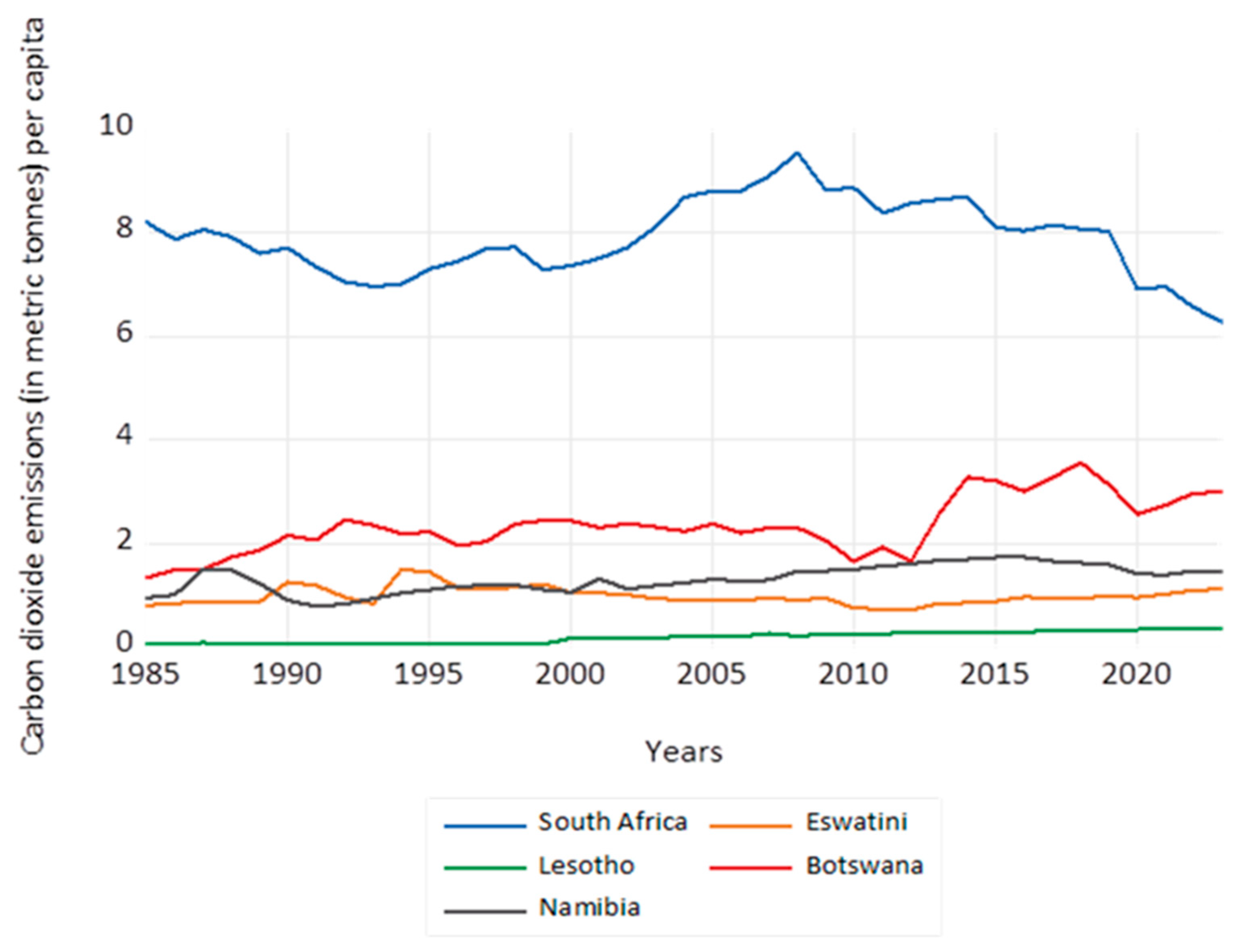

Figure 1 below is a basic line graph plotted as a panel of combined cross-sections, which shows trends in pollution of the environment proxied by CO

2 (carbon emission) in metric tonnes per capita for each SACU country member.

Figure 1 shows that, on average, CO

2 emissions remained stable in Lesotho from 1985 to 2023, while in Eswatini, there has been a slight decline in 1993, 2011, and 2012 to just below 1, followed by an increase. CO

2 emissions in South Africa and Botswana are above those of all other SACU members, with South Africa above the rest of the countries between 1985 and 2023. Both Botswana and South Africa showed a considerable increase in carbon emissions per capita in 2014.

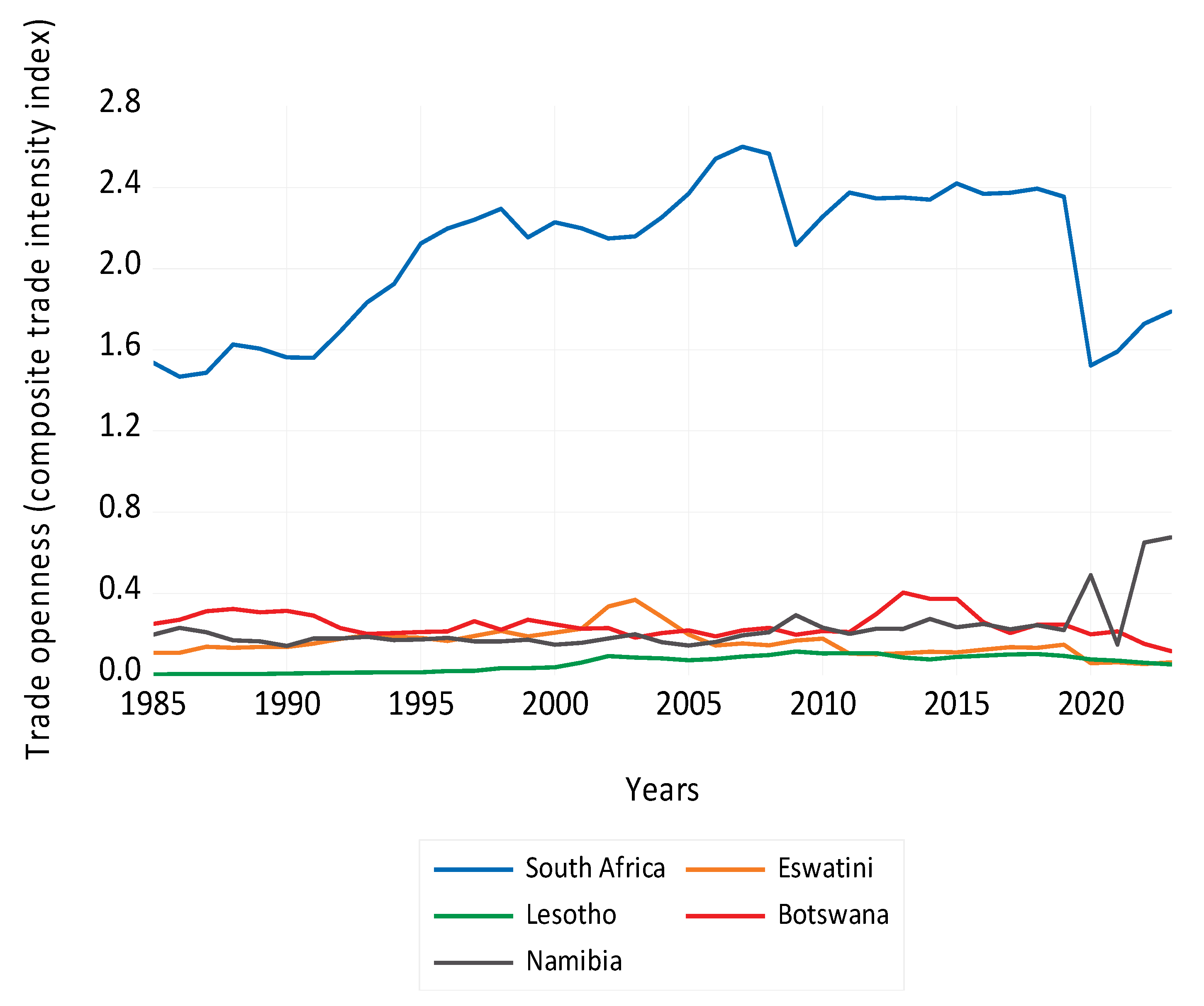

Figure 2 shows a basic line graph plotted as a panel of combined cross-sections to show trends in trade openness proxied by the composite trade index for each SACU country member. In South Africa, CO

2 emissions in metric tonnes per capita continued to rise until 2008. Despite some fluctuation, trade openness generally increased from 1994 to 2008 before declining in 2009. After 2009, the composite index increased steadily in South Africa until 2020. Furthermore, the composite trade index for other SACU members also suggests similar patterns, although it is below that for South Africa. The link between trade openness and carbon emissions could explain the same pattern in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. It can be seen from the graphs that the composite index and CO

2 emissions decreased between 2007 and 2009. This could possibly be due to a drop in trade around the same period owing to the financial crisis, during which natural resource exports declined, as did the CO

2 emissions throughout the economies of SACU countries.

However, what remains to be answered is whether trade openness is beneficial or detrimental to environmental quality, particularly carbon emissions, in the SACU bloc. There is a lack of studies focusing on the short-run and long-run relationships between trade openness and environmental quality in the SACU bloc in Africa. There have been mixed findings from several studies that focused on selected Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries (see

Wicaksana & Karsinah, 2022;

Oumarou & Nourou, 2024;

Andriamahery et al., 2022;

Acheampong et al., 2019) and Africa (see

Ibrahim et al., 2021a;

Twerefou et al., 2019;

Mignamissi et al., 2024), without including all SACU member countries, as well as studies that investigated individual countries within the SACU, such as South Africa, as reported by

Kohler (

2013),

Shahbaz et al. (

2013), and

Hasson and Masih (

2017), who found that trade openness improves environmental quality, suggesting that trade openness contributes to lowering CO

2 emissions, but

Dingiswayo et al. (

2023) demonstrated that trade openness significantly increases CO

2 emissions.

L. Wang and Ibrahim (

2024),

Udeagha and Ngepah (

2021), and

Ngepah and Udeagha (

2022) found that trade contributes to rising emissions over time, and their results supported the existence of the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC).

According to

J. Wang et al. (

2024), Namibia, Botswana, and Lesotho are among the top ten African countries in import-based carbon emissions per gross domestic product, while South Africa is dominant in export-based carbon emissions per gross domestic product. This highlights the fact that carbon is embodied in traded items crossing borders. This ignites the complex debate on the relationship between trade openness and environmental quality in SACU.

Van Tran (

2020) and

Shahbaz et al. (

2017) suggested that trade openness is often linked to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, especially in economies that are in developing regions characterised by weak ecological and environmental regulations. However,

Hakimi and Hamdi (

2020) noted that the effects are heterogeneous across regions and are influenced by institutional frameworks, income levels, and the structure of the economies.

In the SACU as a region, notable studies include those of

T. Mosikari (

2024) and

Biyase et al. (

2024), but none of the studies focus on trade openness.

T. Mosikari (

2024) examined the heterogeneous impact of industrialisation on environmental quality, while

Biyase et al. (

2024) looked at the relationship between remittance and CO

2 emissions. Since the SACU as a region shares trade policies and emphasises the need to move away from environmentally damaging economic activities, this study was also motivated by this argument.

The main objective of the investigation in the present study is to examine the short-run and long-run relationships between trade openness and environmental quality in the SACU in the context of the gains-from-trade hypothesis. Furthermore, the direction of causality between environmental equality and trade openness was also examined. The contribution of this study to the literature is that (1) it is the first to investigate the short-run and long-run effects of trade openness in the SACU; (2) the current study uses the comprehensive composite trade index, the dependence ratio, and the ratio of exports to real gross domestic product as proxies for trade openness to enhance the robustness of this estimation technique; (3) the study used a sample of data (1985 to 2023) that enhances the policy debate since there have been major developments in international trade arguments, growing decarbonisation calls, and shifts in environmental policy across Africa.

The Cross-Sectional Autoregressive Distributed Lag (CS-ARDL) approach was employed to examine the short-run and long-run relationships between trade openness and environmental quality. Furthermore, Granger non-causality tests were performed, especially for the Cross-Sectional Autoregressive Distributed Lag (CS-ARDL). This was performed to improve the predictive power and the robustness of the findings, since the study relates to energy and environmental policy. This will enhance the shift in trade policies and environmental policy frameworks in the region.

The findings of this study reveal that the estimated coefficients of trade openness (both proxies) positively and significantly (at the 1% level of significance) lead to carbon emissions in the short run and the long run. This implies that the gains-from-trade hypothesis does not hold in the SACU in either the short run or the long run. Trade openness significantly increases carbon emissions in the long run by a greater coefficient magnitude compared to the short run. Therefore, this can imply that in the SACU region, trade openness is a long-term contributor to poor environmental quality since it leads to an increase in carbon emissions by a higher magnitude. The Dumitrescu–Hurlin Granger non-causality test was employed, and the results show that there is bidirectional causality between CO2 emissions and trade openness, CO2 emissions and economic growth, and CO2 emissions and population growth; unidirectional causality between CO2 emissions and the exports-to-real-gross-domestic-product ratio; and no directional causality between foreign direct investment and CO2 emissions. The empirical findings are robust, owing to the estimation technique employed and the proxies of trade openness used.

The outline of this study is as follows:

Section 2 presents the literature review.

Section 3 describes the research design.

Section 4 discusses empirical analysis.

Section 5 provides the conclusion and policy implications.

2. Literature Review

This section focuses exclusively on the empirical relationship between trade openness and environmental quality. However, the empirical literature on the association of foreign direct investment, population growth, and economic growth with environmental quality will be briefly discussed.

Turning to the empirical literature on the relationship between trade openness and environmental quality, the findings show complex and often contradictory evidence. The empirical literature is grouped as follows: firstly, country-specific studies conducted in South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Eswatini and Lesotho; secondly, regional studies in SACU countries, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and Africa; and thirdly, some international studies that examined the relationship between environmental quality and trade openness in countries in the European Union (EU), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)/US–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA). Therefore, the literature on the relationship between trade openness and environmental quality is divided into three groups.

The first group comprises country-specific empirical studies that explain the link between trade openness and environmental quality in South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Eswatini, and Lesotho. In South Africa, the findings on the relationship between trade openness and environmental quality are mixed, revealing positive, negative, and insignificant effects.

Kohler (

2013),

Shahbaz et al. (

2013), and

Hasson and Masih (

2017) established that trade openness increases environmental quality, suggesting that trade openness contributes to reducing CO

2 emissions due to increased access to cleaner technologies and more efficient production methods. In contrast, a growing branch of the literature demonstrates that trade openness increases environmental deterioration.

Dingiswayo et al. (

2023) demonstrate that trade openness significantly increases CO

2 emissions, affirming the pollution haven hypothesis.

L. Wang and Ibrahim (

2024),

Udeagha and Ngepah (

2021), and

Ngepah and Udeagha (

2022) similarly demonstrated that trade liberalisation contributes to increasing CO

2 emissions in the long run, and they further affirmed the existence of the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC).

In Eswatini,

Sacolo et al. (

2018) found that between 1968 and 2015, even though the country improved its institutional structures, exports continued to be less than imports (trade balance deficit). Furthermore,

Phiri (

2019) investigated the effect of changes in economic activities on the EKC for a period spanning from 1970 to 2014 and found that economic growth significantly increases greenhouse gas emissions in the expansion phase of the business cycle. Still, when economic activities decline, the impact is insignificant. However, both studies,

Sacolo et al. (

2018) and

Phiri (

2019), fail to report on trade openness and environmental quality. Furthermore, empirical evidence on the environmental impact of trade openness in Botswana remains notably limited. Existing country-specific studies by

Malefane (

2020) and

Chiwira et al. (

2024) indicate that trade openness, particularly through an increase in exports, significantly increases economic growth. In Lesotho,

Malefane and Odhiambo (

2019) showed that trade openness has no significant impact on economic growth in either the short run or the long run; however, this was in contrast with the long-run findings by

Makhetha and Rantaoleng (

2017) that trade openness significantly reduces economic growth, but in short run, the results are similar to those of

Malefane and Odhiambo (

2019). Also,

Sanusi and Dickason-Koekemoer (

2024) found no long-run link between economic growth, trade openness, and financial development. In Namibia,

Sunde et al. (

2023) looked at the effects of exports, imports, and trade openness on economic growth and found that imports negatively affect economic growth, but exports and trade openness are positively linked to economic growth. The results were statistically significant. Also, taking into account the non-linear link between the variables,

T. J. Mosikari and Eita (

2020) examined the relationship between the main export sectors and economic growth in Namibia. The results reveal that growth in exports increases economic growth, while the decline in exports lowers economic growth.

Most available studies, which are country-specific, focus on South Africa, even though some SACU members are also exposed to climate change risks. However, in other countries, like Botswana, Lesotho, Eswatini, and Namibia, studies omit environmental variables, despite the resource-dependent nature of SACU economies, which rely heavily on the mining, agriculture, and manufacturing sectors’ exports and imports that are often pollution-intensive.

The second group comprises panel studies, which investigated the link between trade openness and environmental quality in the SACU, SSA, and Africa. In the SACU,

T. Mosikari (

2024) employed the quantile technique to examine the heterogeneous impact of industrialisation on environmental quality, and the results revealed that when industrialisation grew in the 4th to 6th quantiles, so did environmental degradation, but in the 7th to 8th quantiles, there was a negative relationship between industrialisation and environmental degradation.

Biyase et al. (

2024) looked at the relationship between remittance and CO

2 emissions and found that a modified EKC hypothesis holds in the SACU. However, none of the studies attempted to incorporate trade openness into their empirical models.

In Africa,

Twerefou et al. (

2019) analysed the relationship between trade liberalisation and environmental quality for a panel of 30 African countries using the generalised method of moments (GMM) estimation technique. The results revealed a positive relationship between trade openness and CO

2 emissions because of the composition effect, since factor endowment provided a comparative advantage. However, the original results suggest that trade openness enhances environmental quality. However,

Van Tran (

2020) looked at how trade openness influences the environment for a panel of 66 less developed countries, of which the bulk were African countries. Using two-step generalised method of moments (GMM) estimators, which included a finite-sample correction, the results revealed that trade openness increases emissions due to industrial growth and regulatory weaknesses, and this suggests the existence of the pollution haven hypothesis.

Ibrahim et al. (

2021a) explored various channels to determine whether trade influences environmental pollution (CO

2 emissions) in a panel of 47 African countries, and the study employed the dynamic GMM estimation technique. The results showed a statistically significant positive relationship between trade and CO

2 emissions. Also, the results failed to substantiate the claim of a turning point between the variables.

Also,

Mignamissi et al. (

2024) examined the link between CO

2 emissions and trade openness using the Two-Stage Least Squares technique. Despite the elasticity coefficients differing depending on the proxies used for trade openness, the overall results validated the PHH.

In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA),

H. Sun et al. (

2020) empirically analysed the link between CO

2 emissions, energy consumption, trade openness, and economic growth. The results showed a cointegrating link amongst variables. Furthermore, the study found that in the long run, trade decreases environmental pollution.

Wicaksana and Karsinah (

2022) explored the impact of the effect of trade openness, energy, technology, and population on the environmental performance index. Using the panel data regression techniques, the results suggest a positive and significant impact of trade openness, energy, and population on the environmental performance index. In the study by

Andriamahery et al. (

2022), who used the panel GMM technique, the results revealed that trade has a positive relationship with nitrous oxide, agricultural methane, and CO

2 emissions for the selected countries in SSA and its income groups.

Okelele et al. (

2022) investigated the effect of international trade (proxied by trade openness and foreign direct investment flows) on environmental quality (proxied by ecological footprint) in 23 SSA countries and concluded that ecological footprint in per capita terms is negatively correlated with trade openness but positively correlated with foreign direct investment inflows.

Oumarou and Nourou (

2024) also found that in a panel of 38 SSA countries, trade openness increases CO

2 emissions.

Acheampong et al. (

2019) used data from 1980 to 2015 for 46 Sub-Saharan African countries to study the effect of globalisation (foreign direct investment and trade openness) and renewable energy on CO

2 emissions. Using the first-generation panel data techniques, namely, fixed and random effects, the study found that renewable energy and foreign direct investment contribute to lowering carbon emissions, whereas trade openness harms the environment. Furthermore, by making use of time-series data spanning from 1975 to 2020,

Ewane and Ewane (

2023) explored the effects of trade openness and foreign direct investment (FDI) on environmental degradation in selected SSA countries in the context of the EKC; one of the key findings suggests that trade openness and FDI contribute to lowering CO

2 emissions in the short run while increasing it in the long run.

Besides the aforementioned classification of the above empirical research, results on the link between trade openness and environmental quality around the globe as a result of different trade agreements based on trade blocs, such the European Union (EU), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)/US–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), are also mixed, revealing positive, negative, and insignificant effects. For example, in the EU,

Tachie et al. (

2020) obtained results that supported the presence of the EKC, pollution halo, and PHH. The Dumetriscu–Hurlin Granger causality test results suggest that unidirectional Granger causality exists, from trade openness to CO

2 emissions. Using the fully modified ordinary least squares,

Al-Mulali et al. (

2015) revealed that GDP growth, urbanisation, and financial development increase CO

2 emissions in the long run, while trade openness reduces them.

Le et al. (

2016) found that openness appears to lead to environmental degradation for the global sample. Moreover,

Destek et al. (

2018) found that trade openness decreases environmental degradation in EU countries, but

Nam and Ryu (

2024) indicated that trade initially negatively impacts the environment through greater CO

2 emissions but eventually contributes to a reduction in CO

2 emissions beyond a certain threshold.

Ling et al. (

2020) noted that trade openness and carbon dioxide emissions do have a positive relationship among ASEAN-5 countries. The results reveal that only foreign direct investment is related to trade openness in the long run, while all the other variables, namely, carbon dioxide emissions, economic growth, and energy consumption, show both short-run and long-run relationships with trade openness in ASEAN-5 countries. However,

A’yun and Khasanah (

2022) found that economic growth lowers environmental quality, while trade openness (exports and FDI) leads to growth in CO

2 emissions in ASEAN countries.

Hu et al. (

2021) found that trade openness increases CO

2 emissions, but foreign direct investment, gross domestic product, and patents lower CO

2 emissions in ASEAN countries.

Mahrinasari et al. (

2019) found that trade liberalisation has a significant positive impact on carbon dioxide emissions in ASEAN countries. This was further supported by

Burki and Tahir (

2022), who revealed that trade openness and financial development increase environmental degradation in ASEAN countries. In the context of USMCA countries,

Gómez and Rodríguez (

2020) proxied environmental quality by ecological footprint to explore the presence of the Environmental Kuznets Curve in the USMCA countries. Using the method of moments quantile regression technique, the results suggest that trade openness has no significant effect on environmental quality in the USMCA countries, and only renewable energy was found to be a variable that significantly lowered environmental degradation. However, the results from the study by

Miranda et al. (

2020) indicated that the EKC hypothesis holds in both Mexico and the United States of America (USA) but does not hold in Canada.

Foreign direct investment inflows also continue to be an influential factor, especially for the destination countries. FDI inflow may have either benefits or detrimental effects on the environment of the receiving country. The study by

Huay et al. (

2022) suggests that polluting firms from developed nations reallocate their production units to less developed nations via direct investment.

Ali et al. (

2022) found that FDI inflows negatively influence the environmental quality via the PHH. On the contrary, the pollution halo hypothesis suggests that foreign investments can improve environmental quality in the receiving countries, since foreign firms can bring clean and efficient technical knowledge. Therefore, domestic industries may improve overall ecological quality, as suggested by the results of studies by

C. Sun et al. (

2017) and

Ahmad et al. (

2021). Several authors have explored the link between foreign direct investment inflow and environmental quality in the context of the PHH, such as

Tsoy and Heshmati (

2023),

Qamruzzaman (

2023), and

Musah et al. (

2022), and yielded inconclusive and mixed results. Therefore, it is argued that foreign direct investment (FDI) inflow into the SACU economies may be of great importance, especially in the era of green and sustainable growth and clean energy consumption calls.

Changes in environmental quality can depend on population growth patterns. According to

Tal (

2025), growth in population leads to irreversible effects on the environment.

Martínez-Zarzoso and Maruotti (

2011) pointed out that, in some scenarios, population density leads to better environmental outcomes. This is due to the role of economies of scale in energy use and more efficient infrastructure. However, in the study by

Rehman et al. (

2021), the results indicate that population growth generally contributes to higher

emissions. Also,

Dimnwobi et al. (

2021) investigated the nexus between population changes and environmental degradation in five selected countries in Africa. The results indicate that population growth increases environmental decay.

Economic growth contributes to environmental quality, and the link is embodied in the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis. The study by

Hunjra et al. (

2024) found a positive relationship between economic growth and

emissions in the early stages, but at a later stage, the relationship became negative.

Phiri (

2019) found that economic growth significantly increases greenhouse gas emissions in the expansion phase of the business cycle.

Olaoye (

2024) investigated the relationship between

emissions and economic growth in African countries, and the results indicate that

emissions increase economic growth.

Throughout the literature, studies which focused on the SACU region as a bloc in Africa have not investigated the short-run and long-run relationships between trade openness and environmental quality. Apart from mixed findings, several studies focus on selected Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and Africa without including all SACU member countries or investigating individual countries within the SACU. In the SACU as a region, notable studies include

T. Mosikari (

2024) and

Biyase et al. (

2024), but none of the studies focus on trade openness.

T. Mosikari (

2024) examined the heterogeneous impact of industrialisation on environmental quality, while

Biyase et al. (

2024) looked at the relationship between remittance and CO

2 emissions. Furthermore, the study used the traditional trade openness measures (exports-to-real-gross-domestic-product ratio, dependency ratio) and the composite trade index, which is a comprehensive measure for evaluating whether trade openness influences environmental quality. Therefore, the existing literature still lacks evidence on the relationship between trade openness and environmental quality based on the Cross-Sectional Autoregressive Distributed Lag (CS-ADRL), and as suggested by

Bergougui and Zambrano-Monserrate (

2025), Granger non-causality tests were employed to improve the predictive power, especially since the study relates to energy and environmental policy, which was ignored by various studies.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the short-run and long-run relationships between trade openness and emissions, along with other key regressors, including population growth, foreign direct investment inflow, and economic growth, in five SACU member countries from 1985 to 2023. The results of CS-ARDL estimation reveal that trade openness (CTI and DRA) has a positive and statistically significant relationship with emissions in both the long run and the short run. When trade openness is proxied by the ratio of exports to real gross domestic product (X/RGDP), the results show a statistically significant long-run relationship. FDI and RGDP are statistically insignificant in both the long run and short run, while PPNGR is statistically significant in the long run and short run. The key findings that can be drawn from this study are as follows:

The positive and significant long-run and short-run links between trade openness and carbon emissions in the SACU region invalidate the gains-from-trade hypothesis by providing evidence of the important role played by trade openness in the region.

Foreign direct investment inflow in the SACU region does not significantly influence carbon emissions in either the short run or long run, and this invalidates the pollution haven hypotheses, while population growth has a significant influence in the short run and long run.

There are positive but insignificant short-run and long-run relationships between economic growth and environmental pollution in the SACU region.

The Dumitrescu–Hurlin Granger non-causality test shows two-way causality between carbon emissions and trade openness, bidirectional causality between carbon emissions and economic growth, two-way causality between carbon emissions and population growth, unidirectional causality between the exports-to-real-gross-domestic-product ratio and carbon emissions, and no directional causality between foreign direct investment and carbon emissions.

The invalidation of the gains-from-trade hypothesis in the short and long run, which asserts that trade openness can lead to better environmental equality in the SACU region, has policy implications. The main objective of the SACU is to enhance free trade among its member countries, but in its strategic plan for 2022–2027, the SACU admits that it is deeply concerned about environmental quality and stresses the need to move away from ecologically destructive economic activity to eco-friendly economic activities. The strategic plan suggests that significant advances should be made in new industrial production techniques, commodity demand, and trade, along with changes in investments. The findings of this study suggest the need to readjust trade policies and regulations across the SACU. The strategic plan, which aims to intensify the industrial base of the bloc and stimulate sectoral complementarities in production and encourage industries to diversify across the bloc, should be implemented with great emphasis on the environmental implications. Furthermore, the SACU’s strategic plan for 2022–2027 outlines the integrated approaches and practical initiatives to encourage industrialisation, while at the same time positioning the bloc to fully capitalise on opportunities afforded by the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which would enhance trade integration and openness among several countries in Africa. However, as shown by the findings, trade openness is one of the main factors that increase CO2 emissions; SACU countries need to intensify the trade of environmentally friendly goods.

Also, this two-way causality between trade openness and carbon emissions further enhances the complexity of the relationship. However, it may imply that in the SACU region, with growth in the rate at which the environment is being polluted, owing to the mining and agriculture sectors’ activities, countries may impose restrictions on trade in goods that are unfriendly to the environment. This encourages companies to embrace green technology and trade in environmentally friendly products. However, companies may be reluctant, as in most SACU countries, the main source of electricity is coal; therefore, companies may be reluctant to adopt renewable energy sources. Consequently, SACU countries may actively engage in efforts to combat climate change and embrace trade in environmentally friendly products.

The results show positive and insignificant short-run and long-run relationships between economic growth and environmental pollution in the SACU region. This implies that growth in the region is not linked to detrimental effects on the environment. However, this is not surprising because the majority of SACU countries have poor adoption strategies for industrialisation while acknowledging the complex nature of the link between economic growth and carbon emissions in the region. Furthermore, the finding of two-way causality between economic growth and carbon emissions implies that, in the SACU, there is a need for a balanced and holistic approach that acknowledges the extent to which economic growth and environmental factors are related. The study further revealed that foreign direct investment inflow in the SACU region does not strongly and significantly influence carbon emissions in the long run or short run. This implies that FDI perhaps does not significantly influence carbon emissions, because the SACU region’s environmental policies may be yielding improved carbon emission outcomes.

Also, the results show that population growth negatively and significantly influences carbon emissions in both the long run and short run. This may imply that the impact of population growth in the SACU on CO2 emissions may have been too small to lead to an increase in CO2 emissions compared with other regions; therefore, on average, an individual contributes a negligible amount of carbon, even with population growth. However, the two-way causality suggests that population growth in the SACU may both stimulate and reduce carbon emissions, while carbon emissions can, in turn, affect the population growth rates.

Overall, it is suggested in this study that policymakers in the SACU adopt cap-and-trade arrangements to ensure a clean environment and atmosphere. Since cap-and-trade arrangements make use of emissions trading, firms may act responsibly because they are subject to their total emission quota. Also, SACU governments may encourage the trade of eco-friendly goods, which is more likely to encourage green innovation at a lower total cost.

Despite the contribution of this study to the literature, it has limitations, which may be addressed in future studies. These limitations include, firstly, that the data is from 1985 to 2023, and given the timeframe, the data unavailability in all SACU countries presented considerable constraints. This limited our ability to conduct in-depth and updated research since trade and environmental policies continue to change in the region; therefore, updated data may enhance continuous policy checks and balances in the region. Secondly, future studies could make use of the newly introduced Green Trade Openness Index as a proxy for trade openness and explore long-term and short-term sustainability effects within SACU countries, as well as the future of carbon markets in SACU countries. Also, instead of using carbon emissions, which is an aggregate measure of pollutant sources, such as industrial waste generation, industrial processes, and fugitive emissions, disaggregating the emissions may be of interest for future studies. This is because green trade and cap-and-trade systems (carbon markets) may be industry-specific, but are globally acknowledged as crucial tools to reduce carbon emissions.