Economocracy: Global Economic Governance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

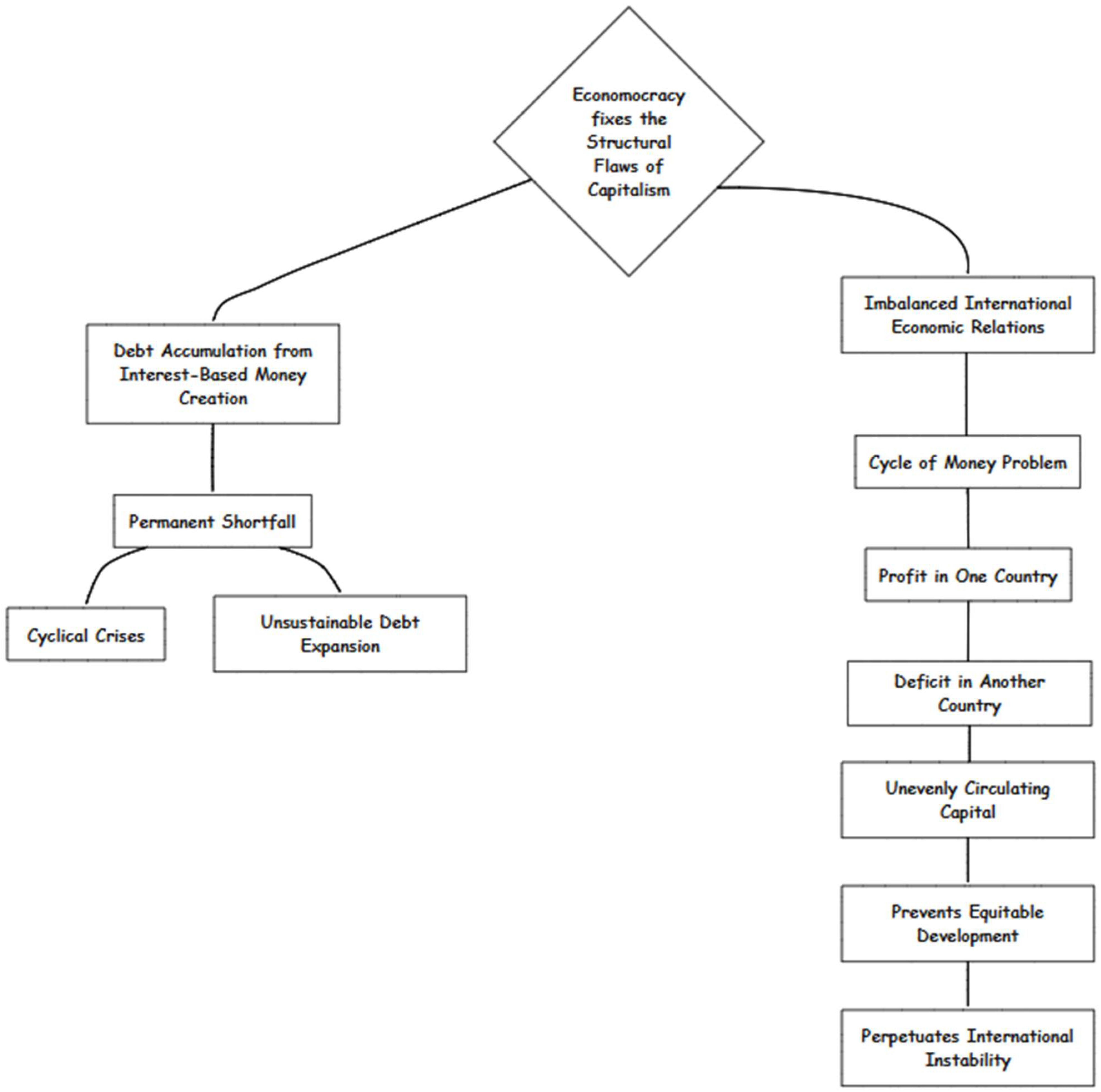

- Debt Accumulation from Interest-Based Money Creation:Under current monetary systems, money is primarily created through bank loans that must be repaid with interest. However, the interest itself is not created within the system, resulting in a permanent shortfall that structurally generates public and private debt. This flaw leads to cyclical crises and unsustainable debt expansion.

- 2.

- Imbalanced International Economic Relations (Cycle of Money Problem):According to the Theory of the Cycle of Money, any profit or surplus generated in one country mathematically implies a deficit in another, due to the finite and unevenly circulating nature of global capital. This zero-sum condition structurally prevents equitable global development and perpetuates international instability (see Figure 1).

2. Literature Review

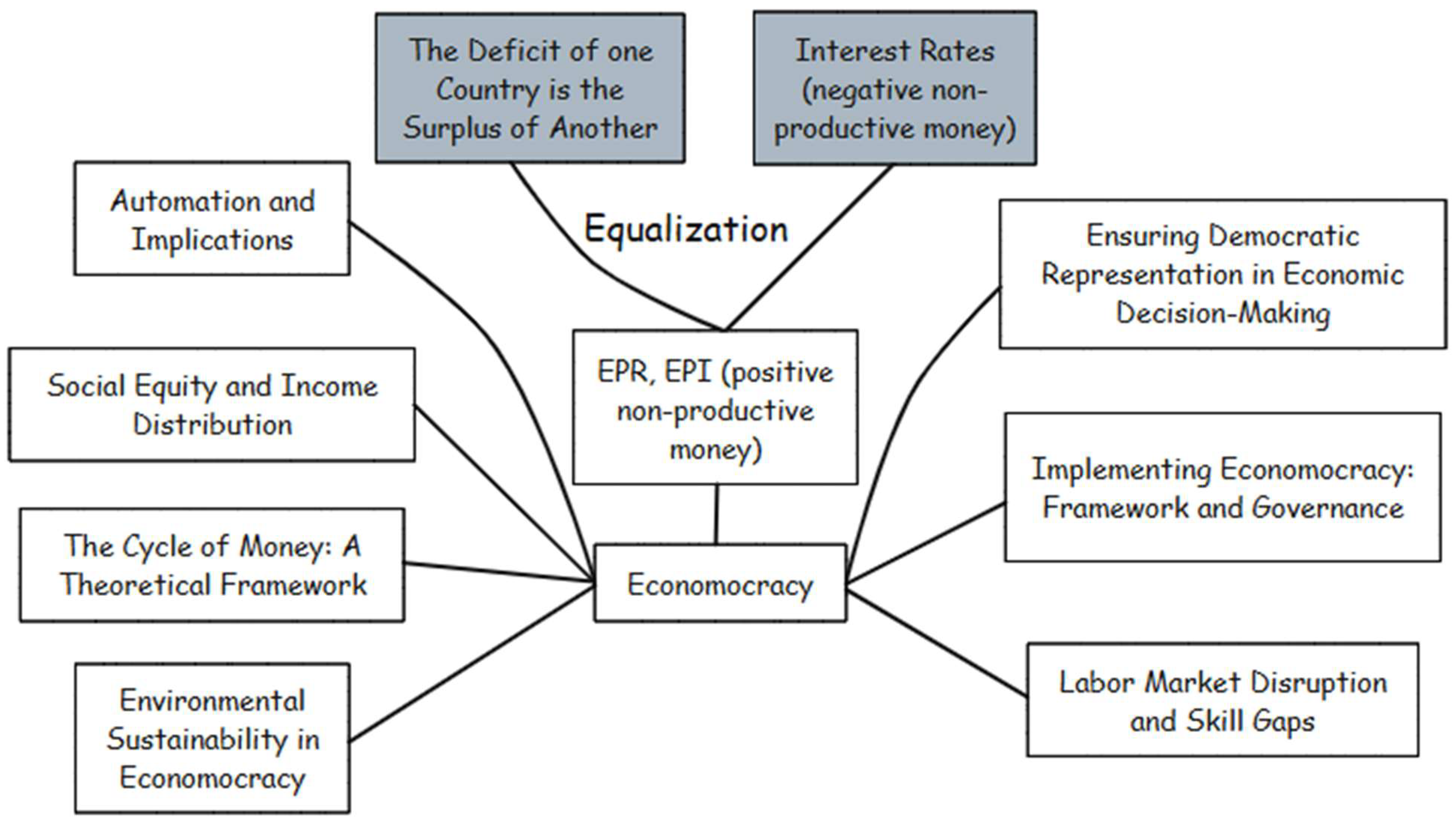

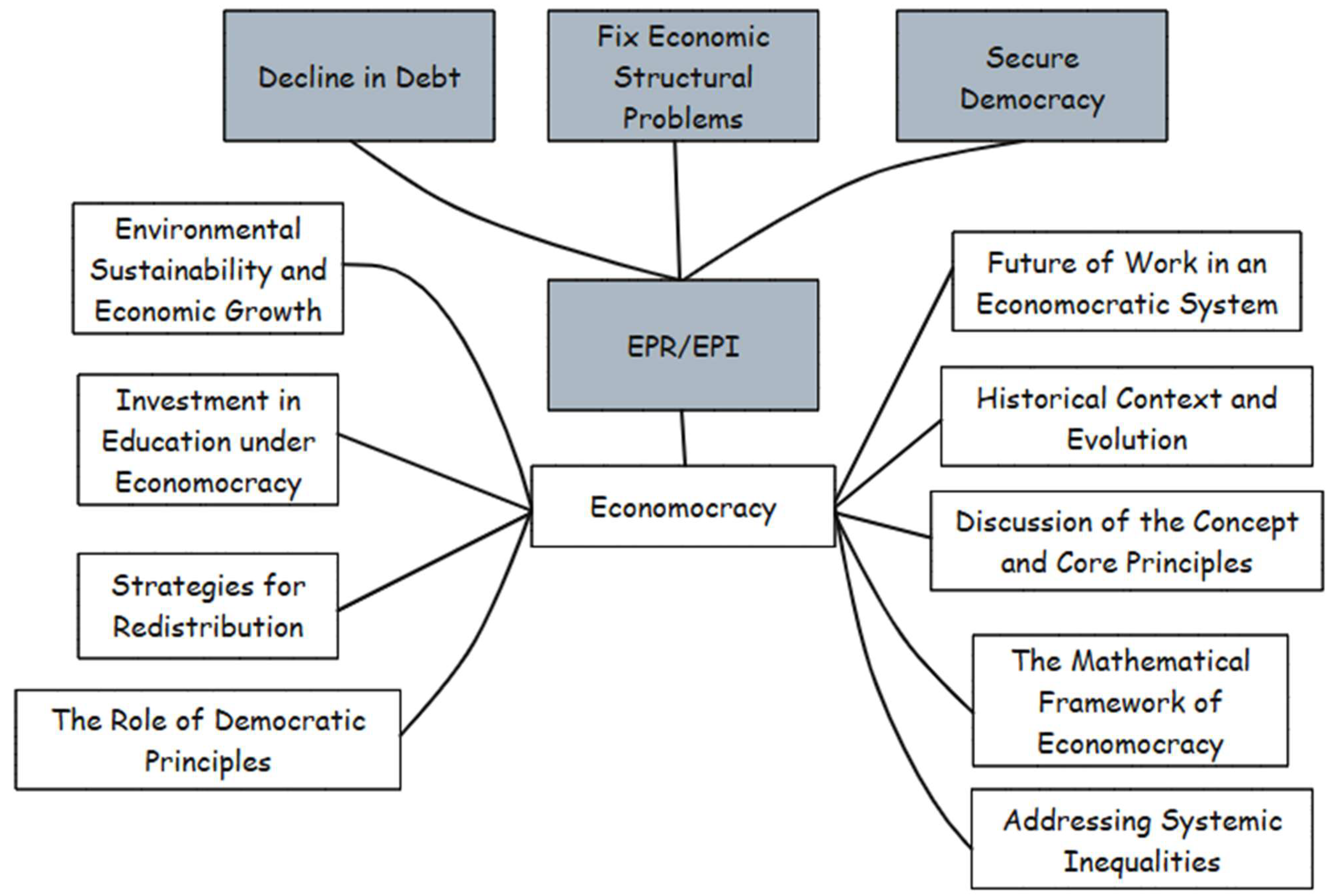

2.1. Economocracy

2.2. Automation and Implications

2.3. Labor Market Disruption and Skill Gaps

2.4. Environmental Sustainability in Economocracy

2.5. Social Equity and Income Distribution

2.6. The Cycle of Money: A Theoretical Framework

2.7. Implementing Economocracy: Framework and Governance

2.8. Ensuring Democratic Representation in Economic Decision-Making

3. Materials and Methods

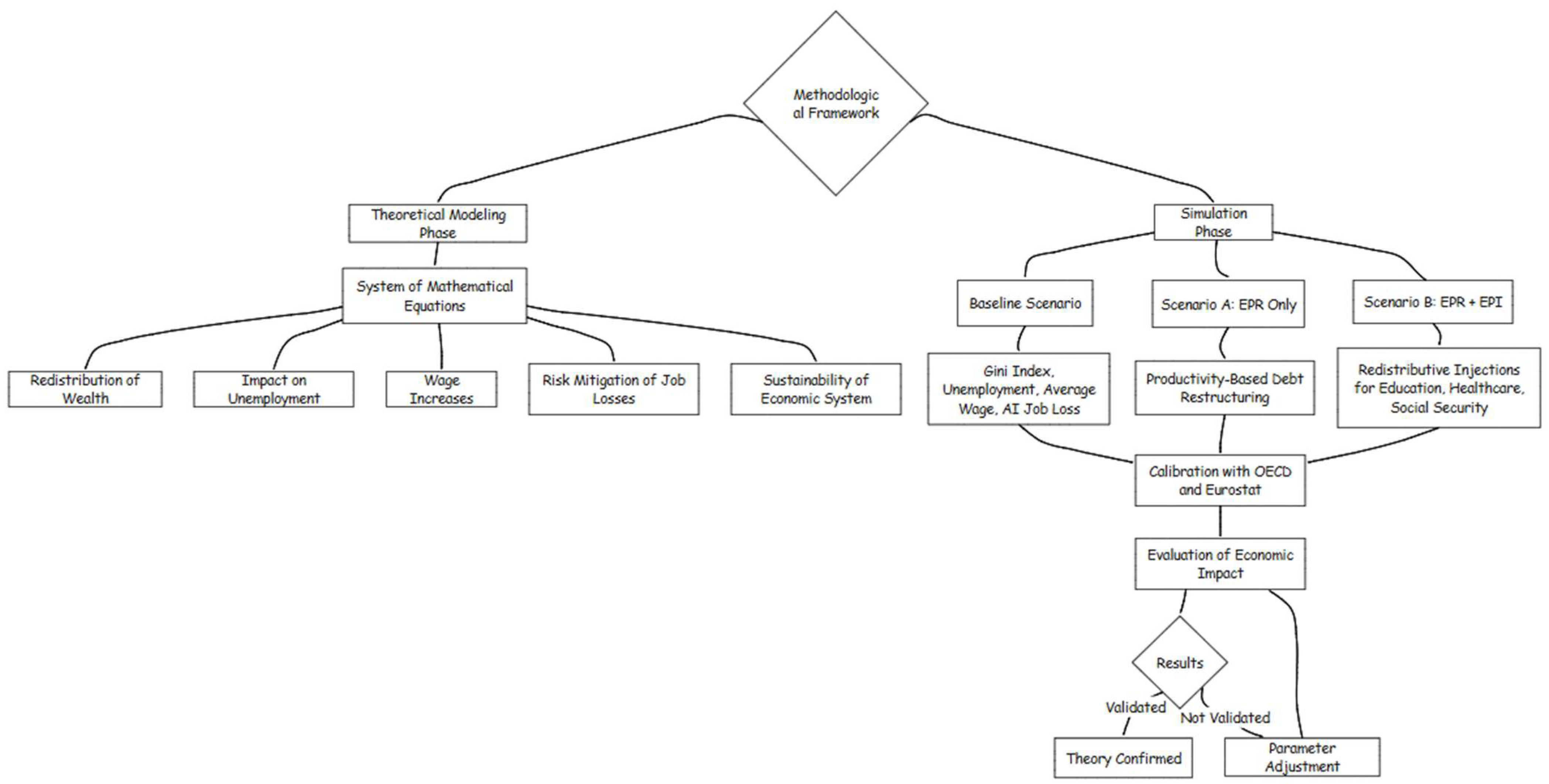

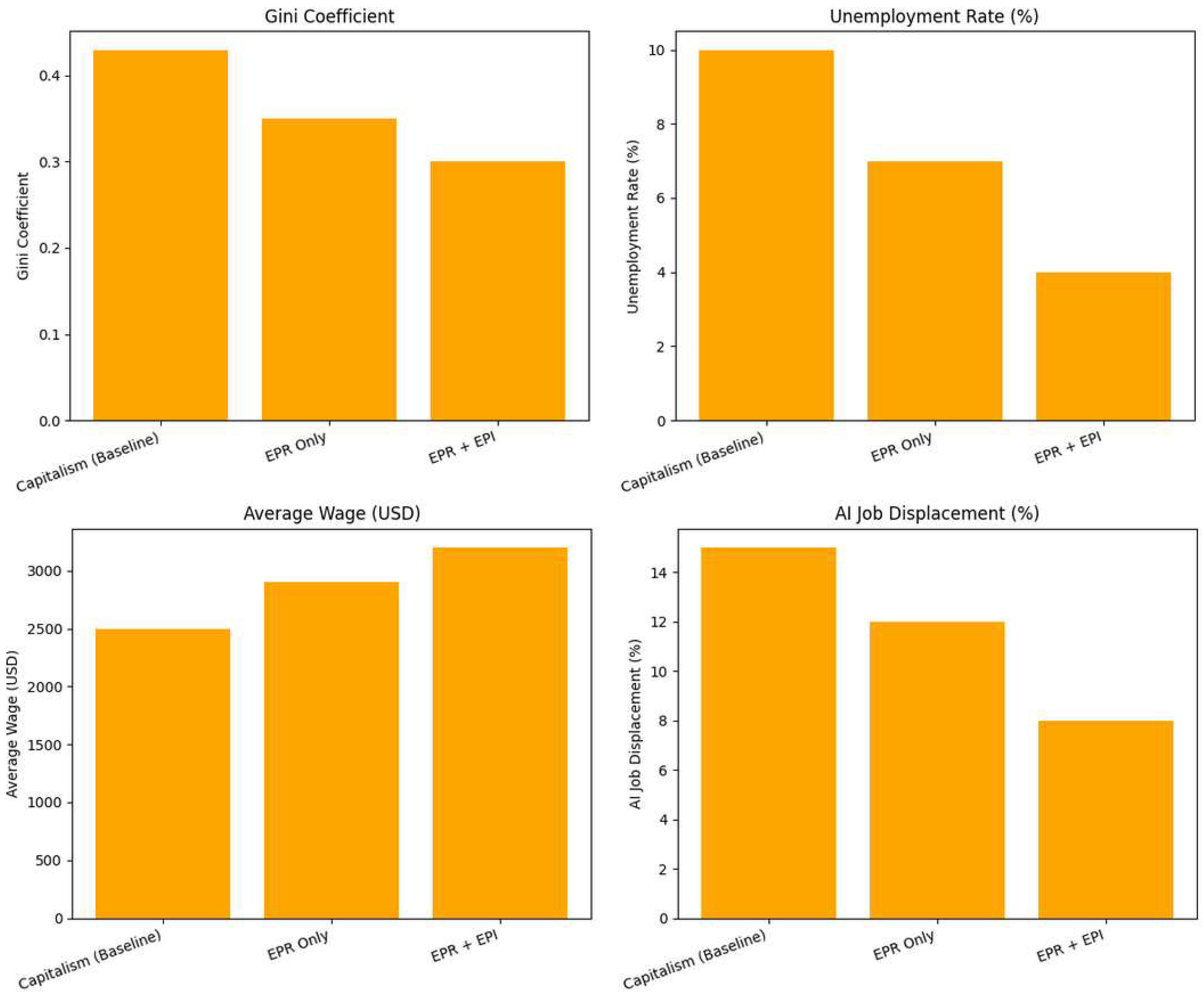

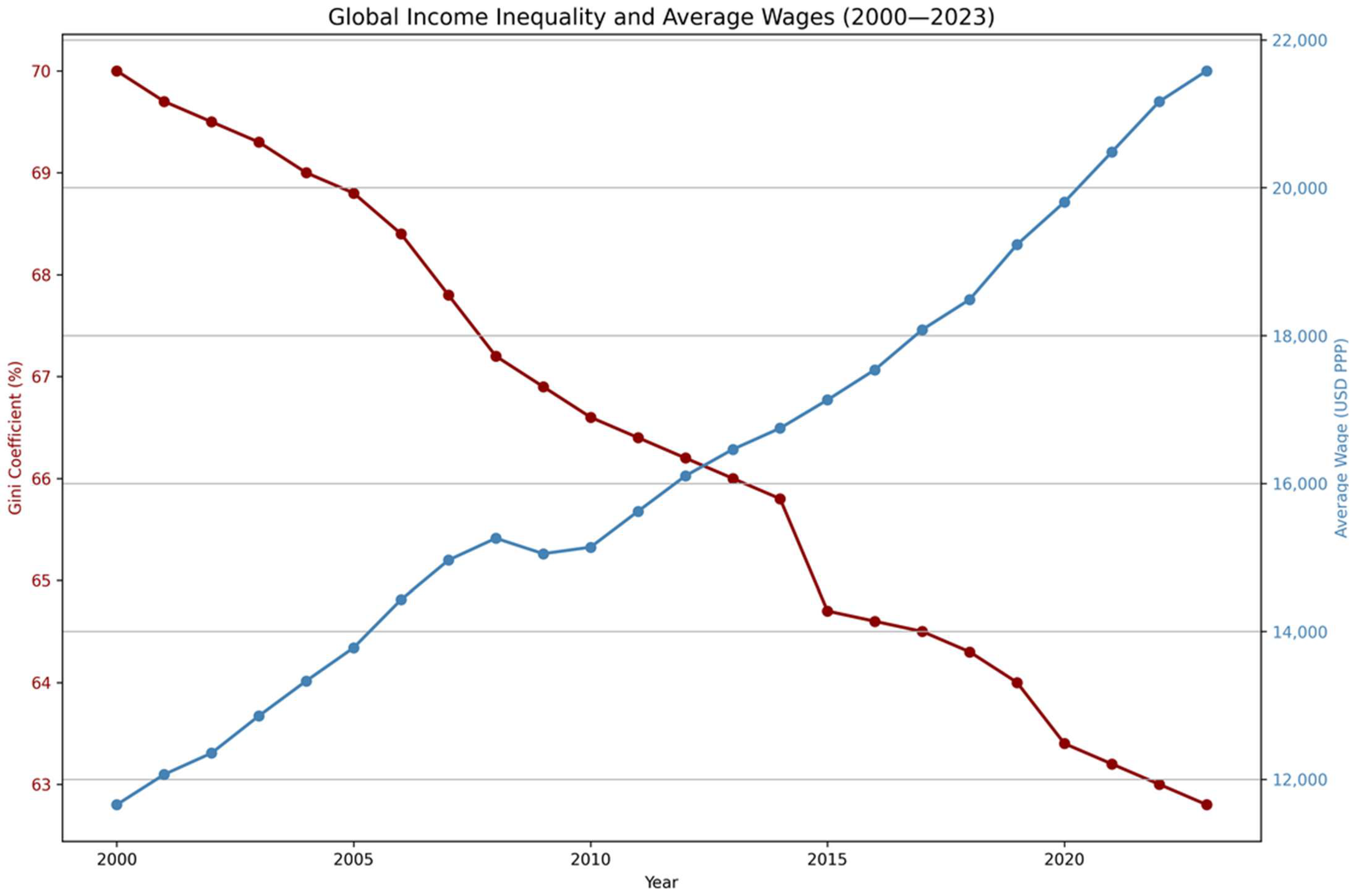

- Redistribution of wealth and inequality levels (via Gini index),

- Impact on unemployment from Economic Productive Resets (EPRs),

- Wage increases under redistributed productivity,

- Risk mitigation of automation-related job losses through targeted EPIs,

- Sustainability of the economic system under a non-debt-based monetary framework.

- Capitalist Baseline: parameters set with Gini index, unemployment, average wage, and AI-induced job loss.

- Scenario A (EPR only): incorporates productivity-based debt restructuring mechanisms.

- Scenario B (EPR + EPI): adds periodic redistributive injections directed to education, healthcare, and social security.

- Gini coefficient: indicator of income inequality.

- Unemployment rate: reflects labor market performance.

- Average wage level: proxy for overall productivity and standard of living.

- AI job displacement (%): represents the risk of automation.

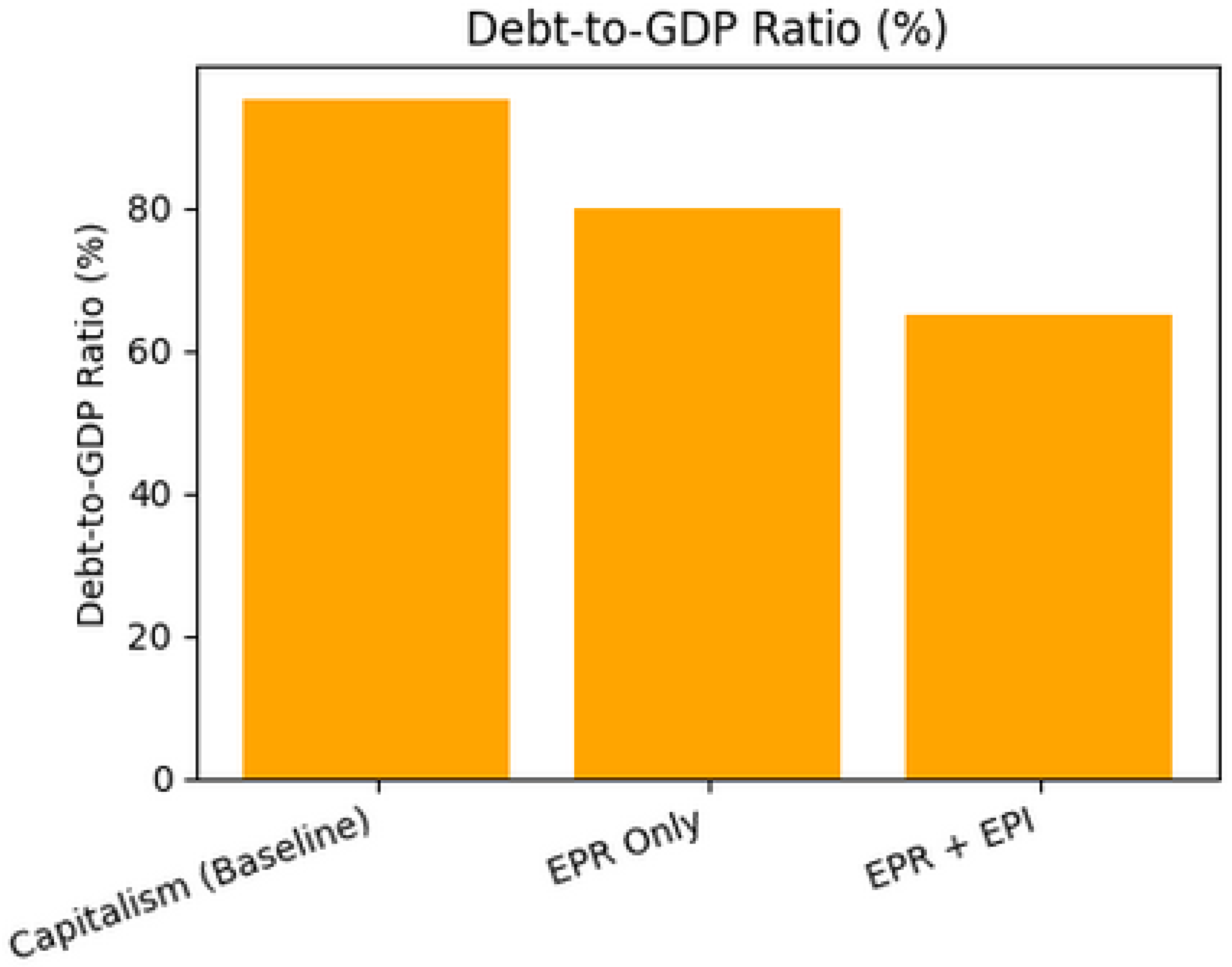

- Debt-to-GDP ratio: used to assess system sustainability.

- Redistributive mechanisms (EPR, EPI): policy tools evaluated for their macroeconomic impact.

4. Results

- Gini Coefficient Values: The baseline Gini coefficient of 0.42 reflects income inequality levels typically observed in advanced capitalist economies, such as the United States or the United Kingdom, as reported by the OECD. This serves as the reference point for the current capitalist model in our simulation. The value of 0.35 in the EPR-only scenario aligns with moderate inequality levels achieved in social-democratic states like Germany or France, where redistributive fiscal policies are in place. The most equitable scenario, at 0.30 under the combined EPR and EPI model, reflects outcomes comparable to Scandinavian countries, where coordinated income redistribution and social investment mechanisms have historically produced low inequality. These values are consistent with international benchmarks and align with the expected outcomes derived from Equation (12) of the Economocracy model (Abeles & Conway, 2020; Dai & Shen, 2025; Gáspár et al., 2023; Kharazmi et al., 2023; Parsons & Naghshpour, 2024; Raffinetti et al., 2015; Sakaki, 2019; Stark, 2024; Tao et al., 2017; Ursu et al., 2020; H.-Y. Wang et al., 2020; Zavyalov, 2024).

- Unemployment Rate: A baseline unemployment rate of 8.0% was selected based on an average of post-crisis labor market data for OECD countries, capturing typical conditions under capitalist economies with uneven labor absorption. The reduction to 6.0% in the EPR-only scenario simulates the effect of productivity-based debt restructuring and job stimulus that accompanies macroeconomic resets. The further decline to 4.5% in the EPR + EPI scenario results from targeted public investment in education, healthcare, and retraining programs that enhance employability. These projections are consistent with empirical trends observed in coordinated market economies and are grounded in Equation (13) of the model, which links job creation and retraining investment to labor market improvement (Balakrishnan & Michelacci, 2001; Belot & Ours, 2001; Bhattarai, 2016; Azmat et al., 2004; Khraief et al., 2020; Koç et al., 2021; Omay et al., 2021; Sahnoun & Abdennadher, 2020; Solarin et al., 2024).

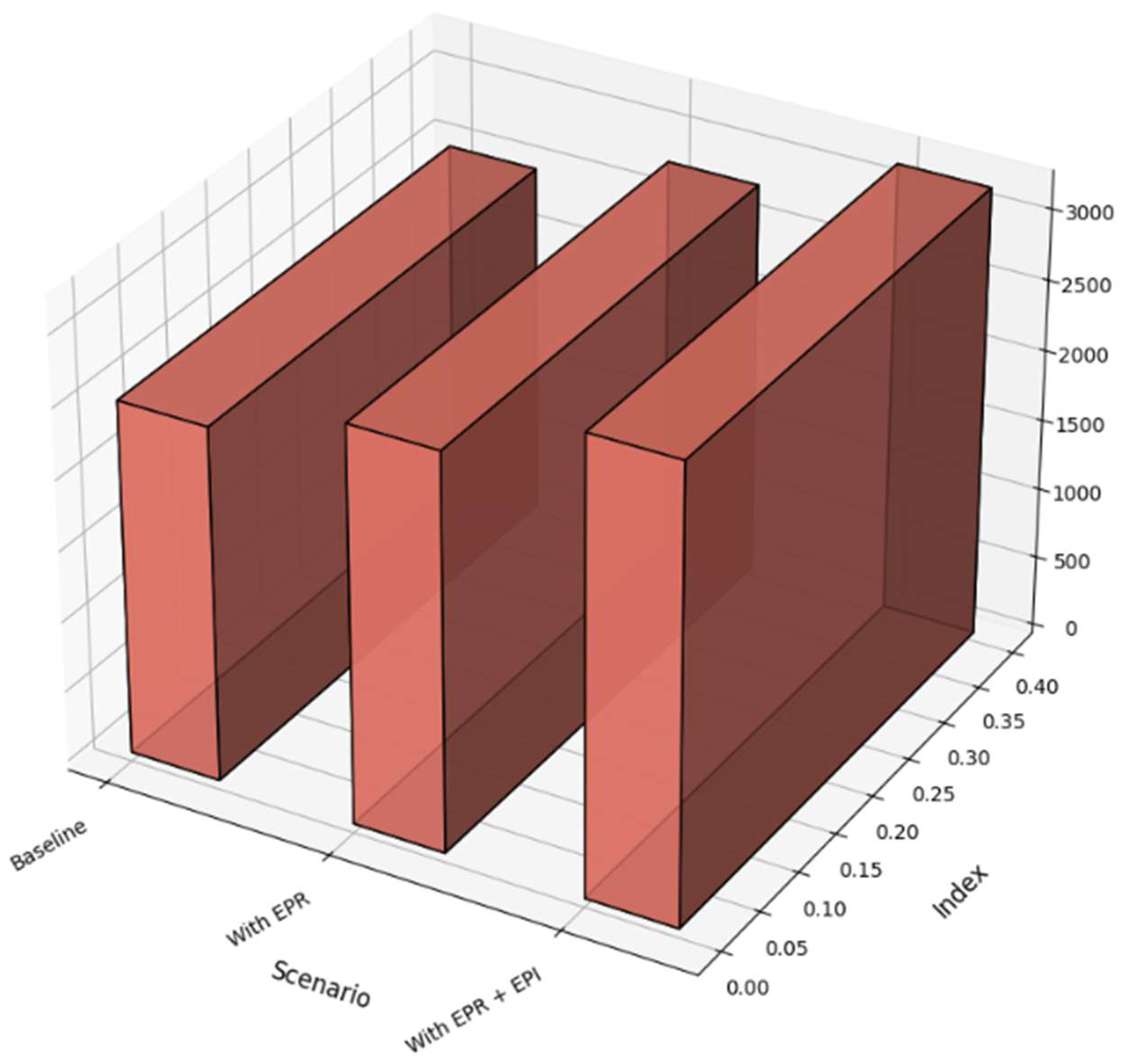

- Average Wages: The baseline average monthly wage of USD 2500 represents typical gross earnings across OECD member states and is used to simulate income conditions under the current capitalist structure. The increase to USD 2800 in the EPR-only scenario models productivity redistribution from non-productive monetary reform. The value of USD 3200 in the EPR + EPI scenario reflects amplified wage gains due to enhanced social investment, educational attainment, and health infrastructure. These upward adjustments are simulated using Equation (14), which expresses wage growth as a function of productivity enhancement and redistribution magnitude. The progression in wage levels across scenarios is grounded in observed patterns from economies undergoing post-crisis wage recovery and structural reform (D. Baker, 2007; Dew-Becker & Gordon, 2005; Dong et al., 2024; Gerritsen & Jacobs, 2014; Lochner & Schulz, 2022; Lollo & O’Rourke, 2020; Moos, 2019; Vergara, 2022).

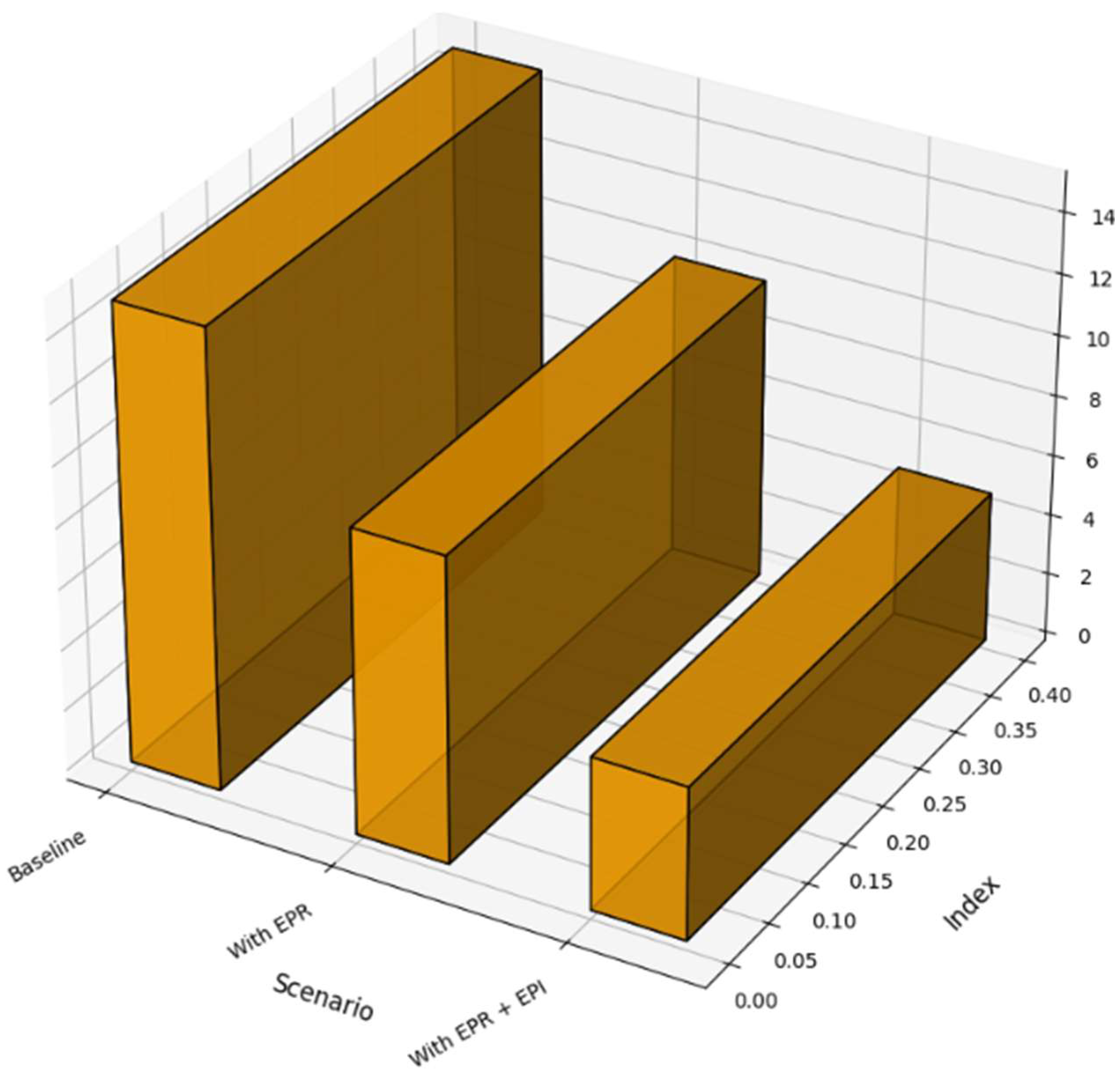

- AI Job Displacement: The simulation assumes a baseline AI-driven job displacement risk of 15%, consistent with projections by McKinsey Global Institute and OECD analyses of automation in high-income economies. In the EPR-only scenario, this risk declines to 10% due to the implementation of counter-cyclical investment and industrial policy reforms. The EPR + EPI scenario lowers the risk further to 5%, simulating the outcome of proactive retraining, sectoral transformation, and employment reallocation, particularly into green and care economies. This evolution is modeled using Equation (15), which adjusts automation displacement according to mitigation investment and labor market adaptability. These estimates correspond to real-world pilot programs where coordinated policies reduced technological unemployment (Camarda et al., 2021; Dahlin, 2024; Jadhav & Banubakode, 2024; Jain, 2023; S. Joshi, 2025; Karangutkar, 2023; Khan et al., 2024; Moradi & Levy, 2020; Shankar, 2024; Soueidan & Shoghari, 2024; Tiwari, 2023; Liu et al., 2023; K. Wang & Lu, 2024; Yang, 2025).

- World Debt (% of GDP):

- Advanced Economies Debt (% of GDP):

- Emerging Market Economies Debt (% of GDP):

5. Implications

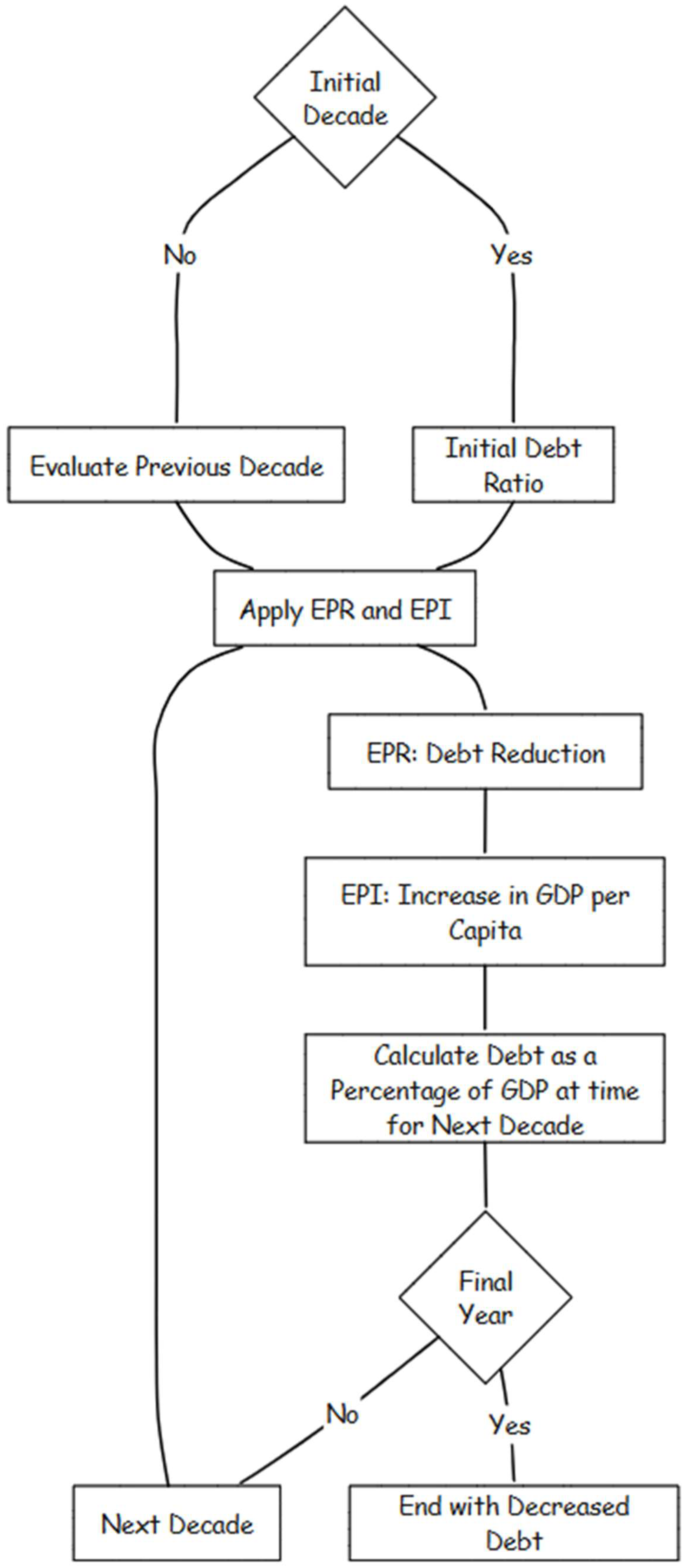

- : debt as a percentage of GDP at time ,

- : initial debt ratio (e.g., baseline year, 1950s),

- : decay rate due to Economic Productivity Reset (),

- : decay rate due to Economic Prosperity Increase (),

- : time index (e.g., number of periods since baseline).

- 1.

- Scenario (GDP-based):This equation reflects the impact of increased systemic productivity on the national debt, assuming that efficiency and automation reduce the need for borrowing to maintain economic growth. Empirical fitting of the model yields

- 2.

- Scenario (GDP per capita-based):This reflects the debt reduction achieved through growth in GDP per capita, driven by improved living standards, education, and technological access. From historical data trends, we have

- 3.

- Combined Scenario:Equivalently, using a compounded decay rate, we haveThis scenario models the strongest and most sustainable decline in debt-to-GDP, under the dual influence of productive efficiency and equitable prosperity (Table 12).

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion of the Concept and Core Principles of Economocracy

6.2. Historical Context and Evolution to Structural Mechanisms

- Preserves the strengths of the free market (as valued by Smith, Friedman, and Hayek) by keeping price mechanisms and private enterprise intact;

- Addresses market failures (as emphasized by Keynes, Sen, and Stiglitz) through automatic rules-based fiscal mechanisms (EPRs and EPIs) rather than arbitrary state control;

- Ensures democratic legitimacy and public accountability (as advocated by Acemoglu and Standing), transforming economic surplus management into a participatory process;

- Reduces inequality and precarity (as discussed by Autor, Standing, and Marx), not through centralized redistribution but through embedded institutional responses grounded in performance, inclusion, and transparency;

- Incorporates ecological sustainability (as stressed by Kallis) by making environmental thresholds a structural part of fiscal decision-making.

6.3. The Mathematical Framework of Economocracy

6.4. Addressing Systemic Inequalities

6.5. Strategies for Redistribution

6.6. An Economocratic System

6.7. Environmental Sustainability and Economic Growth

6.8. Investment in Education Under Economocracy

6.9. The Role of Democratic Principles

6.10. Challenges of Economocracy

7. Limitations and Future Research

8. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

Appendix F

Appendix G

Appendix H

Appendix I

Appendix J

References

- Abdelkafi, I. (2018). The relationship between public debt, economic growth, and monetary policy: Empirical evidence from tunisia. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 9(4), 1154–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeles, J., & Conway, D. (2020). The Gini coefficient as a useful measure of malaria inequality among populations. Malaria Journal, 19(1), 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D. (2001). Book reviews—Comptes rendus. European Review of History: Revue Européenne d’Histoire, 8, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D. (2015). Why nations fail?—(Keynote video lecture). The Pakistan Development Review, 54, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D. (2018). Dave donaldson: Winner of the 2017 clark medal. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 32, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamiak, G. (2006). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes, 3rd ed. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 822–823. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J., Leontief, W., & Duchin, F. (1987). The future impact of automation on workers. Southern Economic Journal, 54, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyeri, T. B. (2024). Economic impacts of AI-driven automation in financial services. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM), 12(7), 6779–6791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A., Derashid, C., & Zhang, H. (2006). Public policy, political connections, and effective tax rates: Longitudinal evidence from Malaysia. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 25(5), 574–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Administration, S. S. (2024). Measures of central tendency for wage data. U.S. Government. Available online: https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/COLA/central.html (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ahmed, Z., Ahmad, M., Rjoub, H., Kalugina, O., & Hussain, N. (2021). Economic growth, renewable energy consumption, and ecological footprint: Exploring the role of environmental regulations and democracy in sustainable development. Sustainable Development, 30(4), 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AICPA. (2017). Guiding principles of good tax policy: A framework for evaluating tax proposals. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. [Google Scholar]

- Almusharraf, A. (2025). Automation and its influence on sustainable development: Economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Sustainability, 17(4), 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M. (2012). Behavioral economics, economic theory and public policy. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, P., & Quintin, E. (2010). Limited enforcement, financial intermediation, and economic development: A quantitative assessment. Wiley-Blackwell: International Economic Review, 51(3), 785–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabyan, O. (2016). Public infrastructure policies and economic geography. Glasnik Srpskog Geografskog Drustva Bulletin of the Serbian Geographical Society, 96(1), 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardakani, O., & Saenz, M. (2023). Evaluating economic impacts of automation using big data approaches. Journal of Data Science and Intelligent Systems, 2(1), 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, K., Featherstone, D., Gidwani, V., & Chari, S. (2022). Series editors’ preface. In Manifesting democracy? Urban protests and the politics of representation in Brazil post 2013. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmat, G., Güell, M., & Manning, A. (2004). Gender gaps in unemployment rates in OECD countries. Journal of Labor Economics, 24, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badmus, A. D. (2023). Leveraging software automation to transform the manufacturing industry. Journal of Knowledge Learning and Science Technology, 2(1), 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D. (2007). The productivity to paycheck gap: What the data show. CEPR reports and issue briefs. Available online: https://consensus.app/papers/the-productivity-to-paycheck-gap-what-the-data-show-baker/3c81d14bf6a153c1bfe457c8c6650c58/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Baker, S. D., Hollifield, B., & Osambela, E. (2020). Preventing controversial catastrophes. Review of Asset Pricing Studies, 10(1), 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, R., & Michelacci, C. (2001). Unemployment dynamics across OECD countries. European Economic Review, 45, 135–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, W. (2024). Gini index (World Bank estimate). World Development Indicators. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=OE (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Bartelsman, E. J., & Beetsma, R. M. W. J. (2003). Why pay more? Corporate tax avoidance through transfer pricing in OECD countries. Journal of Public Economics, 87(9–10), 2225–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baviskar, S., & Malone, M. (2004). What democracy means to citizens—And why it matters. European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, (76), 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belot, M., & Ours, J. (2001). Unemployment and labor market institutions: An empirical analysis. Journal of The Japanese and International Economies, 15, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergler, R., & Borneff, M. (1987). Hygiene als verhaltensproblem [Hygiene as a behavior problem]. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie, Mikrobiologie und Hygiene—Abt. B: Umwelthygiene, Krankenhaushygiene, Arbeitshygiene, Präventive Medizin, 183(4), 384–447. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwati, J. (2008). Democracy and development. Journal of Democracy, 3, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, K. (2016). Unemployment–inflation trade-offs in OECD countries. Economic Modelling, 58, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, Z. (2023). The specter of automation. Philosophia, 51(3), 1093–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S. R., Uddin, M. A., Bhattacharjee, S., Dey, M., & Rana, T. (2022). Ecocentric leadership and voluntary environmental behavior for promoting sustainability strategy: The role of psychological green climate. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(4), 1705–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, J., & Oberfield, E. (2018). Misallocation in the market for inputs: Enforcement and the organization of production (NBER Working Paper Series). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borry, E., & Getha-Taylor, H. (2018). Automation in the public sector: Efficiency at the expense of equity? Public Integrity, 21, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdin, S., & Nadou, F. (2018). French tech: A new form of territorial mobilization to face up to global competition? Annales de Geographie, 2018(723–724), 612–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braudel, F. (1982). The structures of everyday life (Vol. I of civilization and capitalism, 15th–18th century). Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Braudel, F., Reynolds, S., & Reynolds, S. (1981). Civilization and capitalism: 15th–18th century. Vol. 1: The structures of everday life: The limits of the possible. Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y. (2017). Nonlinear analysis of economic growth, public debt and policy tools. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 7(1), 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarda, J., Lee, S., & Lee, J. (2021). The AI displacement risk. In The financial storm warning for investors. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camiña, E., Díaz-Chao, Á., & Torrent-Sellens, J. (2020). Automation technologies: Long-term effects for Spanish industrial firms. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 151, 119828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camous, A., & Gimber, A. R. (2018). Public debt and fiscal policy traps. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 93, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J., Braga, V., & Correia, A. (2019). Public policies for entrepreneurship and internationalization: Is there a government reputation effect? Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 10(4), 975–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, A., Pansini, R. V., & Scandurra, G. (2021). The role of environmental taxes and public policies in supporting RES investments in EU countries: Barriers and mimicking effects. Energy Policy, 149, 112044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2021a). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Belarus. Economy and Banks, 2, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Challoumis, C. (2021b). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Bulgaria. Economic Alternatives, 27(2), 225–234. Available online: https://www.unwe.bg/doi/eajournal/2021.2/EA.2021.2.04.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Challoumis, C. (2021c). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Greece. IJBESAR (International Journal of Business and Economic Sciences Applied Research), 14(2), 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2021d). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Latvia. Economics and Culture, 17(2), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2021e). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Montenegro. Montenegrin Journal for Social Sciences, 5(1–2), 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Challoumis, C. (2021f). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Serbia. Open Journal for Research in Economics (OJRE), 4(1), 1–8. Available online: https://centerprode.com/ojre.html (accessed on 28 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2021g). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Slovakia. Studia Commercialia Bratislavensia Ekonomická Univerzita v Bratislave, 14(49), 176–188. [Google Scholar]

- Challoumis, C. (2021h). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Thailand. Chiang Mai University Journal of Economics, 25(2), 1–14. Available online: https://so01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/CMJE/article/view/247774/169340 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Challoumis, C. (2021i). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Ukraine. Actual Problems of Economics, 243(9), 102–111. Available online: https://eco-science.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/9-10.21._topik_Constantinos-Challoumis-102-111.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Challoumis, C. (2022a). Economocracy versus capitalism. Acta Universitatis Bohemiae Meridionalis, 25(1), 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2022b). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Moldova. Eastern European Journal of Regional Economics, 8(1), 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2022c). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Poland. Research Papers in Economics and Finance, 6(1), 72–86. Available online: https://journals.ue.poznan.pl/REF/article/view/126/83 (accessed on 27 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2023a). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Canada. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Business and Economics, 11(1), 102–133. Available online: http://scientificia.com/index.php/JEBE/article/view/203 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Challoumis, C. (2023b). Index of the cycle of money: The case of Costa Rica. Sapienza, 4(3), 1–11. Available online: https://journals.sapienzaeditorial.com/index.php/SIJIS (accessed on 15 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2023c). Index of the cycle of money—The case of England. British Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 26(1), 68–77. Available online: http://www.ajournal.co.uk/HSArticles26(1).htm (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Challoumis, C. (2023d). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Ukraine from 1992 to 2020. Actual Problems of Economics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2024a, July 31). Economocracy’s equalizer. International Conference on Science, Innovations and Global Solutions (pp. 320–324), Poland. Available online: https://futurity-publishing.com/international-conference-on-science-innovations-and-global-solutions-archive/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Challoumis, C. (2024b). Index of the cycle of money—The case of Georgia. Economic Profile, 19(2(28)), 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2024c). Integrating money cycle dynamics and economocracy for optimal resource allocation and economic stability. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(9), 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2024d). Quantitative analysis of money cycle and economic stability in economocracy. Research Papers in Economics and Finance, 8(2), 149–171. Available online: https://journals.ue.poznan.pl/REF/article/view/1709/1019 (accessed on 1 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2024e). Revolutionary constitutions: The history, economocracy, and cycle of money in the formation of greek independence. Open Journal for Studies in History (OJSH), 7(2), 73–80. Available online: https://centerprode.com/ojsh/ojsh0702/ojsh-0702.html (accessed on 15 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2024f). Rewarding taxes on the cycle of money. Social and Economic Studies within the Framework of Emerging Global Developments, 5, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Challoumis, C. (2024g). The index of the cycle of money: The case of Switzerland. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(4), 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challoumis, C. (2024h). Transfer pricing and tax avoidance effects on global and government revenue. National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Available online: https://www.didaktorika.gr/eadd/handle/10442/56562 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Challoumis, C. (2024i). Transforming qualitative data across scientific disciplines (pp. 111–117). Complex System Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Challoumis, C. (2025). How philosophy shapes economic theories and data interpretation (Working Paper). Academia.edu & ResearchGate. [Google Scholar]

- Challoumis, C., & Eriotis, N. (2025). The impact of artificial intelligence on the Greek economy. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 11(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., Lakshminarayanan, V., & Santos, L. (2005). The evolution of our preferences: Evidence from capuchin-monkey trading behavior (Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper, 1524). Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics, Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Chestnut, H. (1965). Social implications of automation. Nature, 208, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiteji, N. (2002). Promises kept: Enforcement and the role of rotating savings and credit associations in an economy. Journal of International Development, 14, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E. (2020). The social credit system: Not just another Chinese idiosyncrasy. Journal of Public and International Affairs. Available online: https://jpia.princeton.edu/news/social-credit-system-not-just-another-chinese-idiosyncrasy (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Chu, J., Williamson, S., & Yeung, E. (2024). People consistently view elections and civil liberties as key components of democracy. Science, 386, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codoceo-Contreras, L., Rybak, N., & Hassall, M. (2024). Exploring the impacts of automation in the mining industry: A systematic review using natural language processing. Mining Technology, 133, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, C., Hislop, D., Taneva, S., & Barnard, S. (2020). The strategic impacts of Intelligent Automation for knowledge and service work: An interdisciplinary review. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 29, 101600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coonley, H. (1941). Making democracy work. Electrical Engineering, 60, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. (2022). Democracy. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/compass/democracy (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Crick, B. (2007). Citizenship: The political and the democratic. British Journal of Educational Studies, 55, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-Soto, N., Martínez-Muñoz, L., Chiva-Bartoll, Ó., & Santos-Pastor, M. (2023). Environmental sustainability and social justice in higher education: A critical (eco)feminist service-learning approach in sports sciences. Teaching in Higher Education, 28, 1057–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, F. (2003). Eco-localism and sustainability. Ecological Economics, 46, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, E. (2024). Who says artificial intelligence is stealing our jobs? Socius, 10, 23780231241259672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P., & Shen, S. (2025). Estimation of the Gini coefficient based on two quantiles. PLoS ONE, 20, e0318833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaher, J. (2022). Automation and the future of work. In The Oxford handbook of digital ethics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, G. (2021). Democracy’s destiny. California Law Review, 109, 1067–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A., Maracajá, K., Batalhão, A., Silva, V., & Borges, I. (2025). Ecotourism and co-management: Strengthening socio-ecological resilience in local food systems. Sustainability, 17(6), 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalopoulou, I., & Karakitsiou, A. (2020). Regional social capital and economic growth: Exploratory evidence from testing the virtuous spiral vs. vicious cycle model for greece. Sustainability, 12(15), 6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delis, M., Staikouras, P., & Tsoumas, C. (2017). Formal enforcement actions and bank behavior. Management Science, 63, 959–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, A. A. A., Alves, M., Macini, N., Cezarino, L., & Liboni, L. (2017). Resilience for sustainability as an eco-capability. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 9, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew-Becker, I., & Gordon, R. (2005). Where did the productivity growth go? Inflation dynamics and the distribution of income. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2005, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, S. Y., Shults, F. L. R., & Wildman, W. J. (2021). Minding morality: Ethical artificial societies for public policy modeling. AI and Society, 36(1), 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamantina, A., & Yulida, D. (2023). Reinforcement of green constitution: Efforts for manifesting ecocracy in Indonesia. In IOP conference series: Earth and environmental science (Vol. 1270). IOP Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, P. A. (1965). National debt in a neoclassical growth model. American Economic Review, 55(5), 1126–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Dodel, M., & Mesch, G. (2020). Perceptions about the impact of automation in the workplace. Information, Communication & Society, 23, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollery, B. E., & Worthington, A. C. (1996). The evaluation of public policy: Normative economic theories of government failure. Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, 7(1), 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X., Hyslop, D., & Kawaguchi, D. (2024). Skill, productivity, and wages: Direct evidence from a temporary help agency. Journal of Labor Economics, 42, S133–S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, N., Badareu, G., & Puiu, S. (2025). Automation systems implications on economic performance of industrial sectors in selected European Union countries. Systems, 13(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, P., Schäfer, D., & Stephan, A. (2024). Macro-financial policy at the crossroad: Addressing climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental degradation—Introduction to the special issue. Eurasian Economic Review, 14(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Benso Maciel, L., Bonatto, B. D., Arango, H., & Arango, L. G. (2020). Evaluating public policies for fair social tariffs of electricity in Brazil by using an economic market model. Energies, 13(18), 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, M., & Gaggl, P. (2015). On the welfare implications of automation. Macroeconomics: Aggregative Models EJournal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2020). Financing the green transition: The European green deal investment plan and just transition mechanism. European Union. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/%5Beuropa_tokens:europa_interface_language%5D/ip_20_17 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Everyman, K. F., Felix, D., & Maynard, J. (1996). Keynes for everyman. The Review of Politics, 58, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, D. (2010). Law enforcement and firm financing: Theory and evidence. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8, 776–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrègue, B. F. G., & Bogoni, A. (2023). Privacy and security concerns in the smart city. Smart Cities, 6(1), 586–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadele, A., Olukoga, G., Oladimeji, J., & Otolley, P. (2023). Is a democratic government a theory or practice in Nigeria: Free and fair elections. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, A., Chen, V., & McDonald, M. (2023). Breaking down the impact of automation in manufacturing. MIT Science Policy Review, 4, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, M. F. S. (2011). Public policy and public administration. Revista de Administracao Publica, 45(3), 813–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjelstul, J. (2022). Explaining public opinion on the enforcement of the stability and growth pact during the European sovereign debt crisis. European Union Politics, 23, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez-Jiménez, M., Lleó, Á., Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Muñoz-Villamizar, A. (2024). Corporate sustainability, organizational resilience, and corporate purpose: A review of the academic traditions connecting them. Review of Managerial Science, 19(1), 67–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franko, W., Tolbert, C. J., & Witko, C. (2013). Inequality, self-interest, and public support for “robin hood” tax policies. Political Research Quarterly, 66(4), 923–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, R. (2020). Democracy and human rights. In Selling war and peace. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. (1940). Creation and effect of personal liability on mortgage debts in New York. Yale Law Journal, 50, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. (1942). The enforcement of personal liability on mortgage debts in New York. Yale Law Journal, 51, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. (1943). Discharge of personal liability on mortgage debts in New York. Yale Law Journal, 52, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. (1993). George stigler: A personal reminiscence. Journal of Political Economy, 101, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallemore, J., & Jacob, M. (2020). Corporate tax enforcement externalities and the banking sector. Journal of Accounting Research, 58(5), 1117–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E., & Prettner, K. (2020). Automation, stagnation, and the implications of a robot tax. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 26, 218–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gáspár, A., Cervone, C., Durante, F., Maass, A., Suitner, C., Valtorta, R., & Vezzoli, M. (2023). A twofold subjective measure of income inequality. Social Indicators Research, 168, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, A., & Jacobs, B. (2014). Is a minimum wage an appropriate instrument for redistribution? In LSN: Compensation law (Topic). Tinbergen Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M., Asadi, S., Iranmanesh, M., Foroughi, B., Mubarak, M., & Yadegaridehkordi, E. (2023). Intelligent automation implementation and corporate sustainability performance: The enabling role of corporate social responsibility strategy. Technology in Society, 74, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilens, M., & Page, B. I. (2014). Testing theories of American politics: Elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspectives on Politics, 12(3), 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, W., Carey, M. P., Halchin, L. E., & Keegan, N. (2013). Government transparency and secrecy: An examination of meaning and its use in the executive branch. In Government transparency and secrecy: Measures, access, and policies. Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Gödöllei, A., & Beck, J. (2023). Insecure or optimistic? Employees’ diverging appraisals of automation, and consequences for job attitudes. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 12, 100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, G. (2014). Data privacy laws in Asia—Context and history. In Asian data privacy laws. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, D. (2016). Process of public policy formulation in developing countries. Faculty of Public Policy. Graduate Academy of Social Science. [Google Scholar]

- Haskel, J., & Westlake, S. (2021). Capitalism without capital: The rise of the intangible economy (an excerpt). Ekonomicheskaya Sotsiologiya, 22(1), 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselman, L., & Stoker, G. (2017). Market-based governance and water management: The limits to economic rationalism in public policy. Policy Studies, 38(5), 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, F. (1944). The road to serfdom: Text and documents: The definitive edition. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, F. (1961). The constitution of liberty. Revue Économique, 13(1), 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holston, J. (2022). What makes democratic citizenship democratic? Citizenship Studies, 26, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howcroft, D., & Taylor, P. (2022). Automation and the future of work: A social shaping of technology approach. New Technology, Work and Employment, 38(2), 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMF. (2025). 2024 global debt monitor. IMF. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/GDD/2024%20Global%20Debt%20Monitor.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Islam, A., Rashid, M. H. U., Hossain, S. Z., & Hashmi, R. (2020). Public policies and tax evasion: Evidence from SAARC countries. Heliyon, 6(11), e05449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T., Drake, B., Victor, P., Kratena, K., & Sommer, M. (2014). Foundations for an Ecological Macroeconomics: Literature review and model development (p. 39). WWWforEurope Working Paper No 65. WWWforEurope. Available online: http://www.foreurope.eu/fileadmin/documents/pdf/Workingpapers/WWWforEurope_WPS_no065_MS38.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Jadhav, R. D., & Banubakode, A. (2024). The implications of artificial intelligence on the employment sector. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesh, D. (2015). The impact of savings in economic growth: An empirical study based on Botswana. Available online: https://consensus.app/papers/the-impact-of-savings-in-economic-growth-an-empirical-study-jagadeesh/5cf676da47dc50cb9e89bc90315521ed/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Jagadeeswari, V., Subramaniyaswamy, V., Logesh, R., & Vijayakumar, V. (2018). A study on medical Internet of Things and Big Data in personalized healthcare system. Health Information Science and Systems, 6(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. (2023). Job displacement due to artificial intelligence and machine learning—A review. International Journal For Multidisciplinary Research, 5(6), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, H., Rohenkohl, B., Arriagada, P., Ortiz-Ospina, E., & Roser, M. (2023). Global Gini coefficient (inequality data): Our world in data. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/economic-inequality (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Joshi, A., Pradhan, S., & Bist, J. P. (2019). Savings, investment, and growth in Nepal: An empirical analysis. Financial Innovation, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S. (2025). Generative AI: Mitigating workforce and economic disruptions while strategizing policy responses for governments and companies. International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Communication and Technology, 5, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldor, N. (1932). A case against technical progress? Economica, 36(36), 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karangutkar, A. A. (2023). The impact of artificial intelligence on job displacement and the future of work. International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Communication and Technology, 3(1), 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpf, D., Ignatieff, M., Przeworski, A., Carothers, T., Hartnett, B., Vaishnav, M., Ríos, V., Malik, A., Tudor, M., Meléndez-Sánchez, M., Vergara, A., Marks, Z., McCargo, D., Wadipalapa, R., Velasco, K., Baral, S., Tang, Y., & Loxton, J. (2024). Documents on democracy. Journal of Democracy, 35, 114–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keynes, J. (1932). Essays in persuasion. Pacific Affairs, 5, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keynes, J. (1937). The general theory of employment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 51, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keynes, J. (2004). The end of laissez faire: The economic consequences of the peace. Available online: https://consensus.app/papers/the-end-of-laissez-faire-the-economic-consequences-of-the-keynes/e2d13b7541105512850dcf22f0332167/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Keynes, J., Johnson, E., & Moggridge, D. (1936). The collected writings of John Maynard Keynes: Fluctuations in net investment in the United States (1936). The Economic Journal, 46, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest, and money. Harcourt Brace. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A., Shad, F., Sethi, S., & Bibi, M. (2024). The impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on job displacement and the future work. Social Science Review Archives, 2(2), 2296–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharazmi, E., Bordbar, N., & Bordbar, S. (2023). Distribution of nursing workforce in the world using Gini coefficient. BMC Nursing, 22, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, M., & Faik, M. (2024). Tourism as a catalyst for resilience: Strategies for building sustainable and adaptive communities. Community Development, 56, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraief, N., Shahbaz, M., Heshmati, A., & Azam, M. (2020). Are unemployment rates in OECD countries stationary? Evidence from univariate and panel unit root tests. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 51, 100838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, A., & Xiao, Q. (2023). Automation in architecture, engineering and construction: A scientometric analysis and implications for management. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 31(8), 3308–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, T., Dünder, E., & Koç, H. (2021). Fractional regression model for investigating the determinants of the unemployment rates in OECD countries. Journal of Science and Arts, 21(2), 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H., Spannring, R., Hawke, S., Robertson, C., Thomasberger, A., Maloney, M., Morini, M., Lynn, W., Muhammad, N., Santiago-Ávila, F., Begovic, H., & Baranowski, M. (2021). Ecodemocracy in practice: Exploration of debates on limits and possibilities of addressing environmental challenges within democratic systems. Visions for Sustainability, 15, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenik, D., & Wegrzyn, M. (2020). Public policy timing in a sustainable approach to shaping public policy. Sustainability, 12(7), 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J., & Seager, T. (2008). Beyond eco-efficiency: A resilience perspective. Business Strategy and The Environment, 17, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraske, B. (2008). The implications of automation. Journal of The Society of Dyers and Colourists, 95, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. (2023). The transformation of the Indian healthcare system. Cureus, 15(5), e39079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lada, A. (2008). Marrying behavioural economics and growth theory. Behavioral & Experimental Economics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, T. (2019). Lobbying on regulatory enforcement actions: Evidence from U.S. commercial and savings banks. Management Science, 65(6), 2545–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larissa, B., Maran, R., Ioan, B., Anca, N., Mircea-Iosif, R., Horia, T., Gheorghe, F., Speranta, M. E., & Dan, M. I. (2020). Adjusted net savings of CEE and baltic nations in the context of sustainable economic growth: A panel data analysis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(10), 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukyte, M. (2022). Averting enfeeblement and fostering empowerment: Algorithmic rights and the right to good administration. Computer Law and Security Review, 46, 105718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenin, V. I. (1916). Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism. The Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, E., Paolacci, G., & Puntoni, S. (2018). Man versus machine: Resisting automation in identity-based consumer behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 55, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limkar, K. R., & Tamboli, F. A. (2024). Impact of automation. International Journal of Scientific Research in Modern Science and Technology, 3(8), 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, I. (2024). Ironies of automation and their implications for public service automation. Government Information Quarterly, 41, 101974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Meng, X., & Li, A. (2023). AI’s ethical implications: Job displacement. Advances in Computer and Communication, 4(3), 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochner, B., & Schulz, B. (2022). Firm productivity, wages, and sorting. Journal of Labor Economics, 42, 85–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lollo, N., & O’Rourke, D. (2020). Factory benefits to paying workers more: The critical role of compensation systems in apparel manufacturing. PLoS ONE, 15, e0227510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lousley, C. (2020). Ecocriticism. In Oxford research encyclopedia of literature. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, A., & Zuehl, J. (2022). The possibility of democratic autonomy. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 50(4), 467–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenberg-DeBoer, J., Huang, I., Grigoriadis, V., & Blackmore, S. (2019). Economics of robots and automation in field crop production. Precision Agriculture, 21, 278–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lule, E., Mikeka, C., Ngenzi, A., & Mukanyiligira, D. (2020). Design of an IoT-based fuzzy approximation prediction model for early fire detection to aid public safety and control in the local urban markets. Symmetry, 12(9), 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupinacci, J., Happel-Parkins, A., & Turner, R. (2023). Ecocritical perspectives in teacher education. Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, R. (2022). Ecocriticism. The Year’s Work in Critical and Cultural Theory, 30, 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamatzakis, E., Pegkas, P., & Staikouras, C. (2023). The impact of debt, taxation and financial crisis on earnings management: The case of Greece. Managerial Finance, 49(1), 110–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, H., Abbas, S., Rehan, S. T., & Hasan, M. M. (2022). Monkeypox virus: A future scourge to the Pakistani Healthcare system. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 79, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manu, C. A. (2022). Contract enforcement, remittance and economic growth in Ghana. Journal of Economics, Finance And Management Studies, 5, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcet, A., & Marimon, R. (1992). Communication, commitment, and growth. Journal of Economic Theory, 58, 219–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, E. C. L. (2019). Notes on networks, the state, and public policies. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 35, e00002318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, K. (1849). Wage labour and capital. Available online: https://consensus.app/papers/wage-labour-and-capital-marx/c87e9560fdf45bceaa55b2c7a1e1a8bf/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Marx, K. (1981). Research index. South Asia Research, 1, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, K. (2022). The power of money. Marx Matters, 215, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, K., & Engels, F. (2017). The communist manifesto. In The two narratives of political economy. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClellan, C. (2018). Growth effects of VAT evasion and enforcement. Public Finance Review, 47, 530–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIsaac, J. L. D., & Riley, B. L. (2020). Engaged scholarship and public policy decision-making: A scoping review. Health Research Policy and Systems, 18(1), 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messinger, L. (2009). Creating LGBTQ-Friendly Campuses. How activists on a number of campuses eliminated discriminatory policies. American Association of University Professors. [Google Scholar]

- Milakis, D., Arem, B., & Wee, B. (2017). Policy and society related implications of automated driving: A review of literature and directions for future research. Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems, 21, 324–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, K. (2019). Neoliberal redistributive policy: The US net social wage in the early twenty-first century. Review of Radical Political Economics, 51, 581–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, P., & Levy, K. (2020). The future of work in the age of AI. In The Oxford handbook of ethics of AI. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Jiménez, J. M., Pérez-Espés, C., & Velázquez, M. (2014). E-Cognocracy and the design of public policies. Government Information Quarterly, 31(1), 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro Cordero, M. A. (2021). Seguridad y protección de datos (también) en el teletrabajo. Pertsonak eta Antolakunde Publikoak Kudeatzeko Euskal Aldizkaria/Revista Vasca de Gestión de Personas y Organizaciones Públicas, 2021(4), 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munck, G. (2016). What is democracy? A reconceptualization of the quality of democracy. Democratization, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, M., & Rajhi, T. (2013). Banking, contract enforcement and economic growth. International Review of Economics, 60, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, V., Bright, J., Margetts, H., & Lehdonvirta, V. (2017). Public policy in the platform society. Policy and Internet, 9(4), 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaz, A. I., Sikder, A. K., Rahman, M. A., & Uluagac, A. S. (2021). A survey on security and privacy issues in modern healthcare systems. ACM Transactions on Computing for Healthcare, 2(3), 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. N., Tham, J., Khatibi, A., & Ferdous Azam, S. M. (2020). Conceptualizing the effects of transfer pricing law on transfer pricing decision making of FDI enterprises in Vietnam. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 4(2), 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, J., & Manville, B. (2024). Democracy, bargaining, and education. Critical Review, 36, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). Average annual wages. OECD Indicator. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/average-annual-wages.html (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Omay, T., Shahbaz, M., & Stewart, C. (2021). Is there really hysteresis in the OECD unemployment rates? New evidence using a Fourier panel unit root test. Empirica, 48, 875–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2024). Income inequality (indicator). OECD Data. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/inequality/income-inequality.htm (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Parker, W. (1997). Democracy and difference. Theory and Research in Social Education, 25, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, B., & Naghshpour, S. (2024). Political regime and income (re)distribution—Panel data analysis in 126 countries. Economics & Politics, 37(1), 341–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, G. (2018). Macro and micro financial liberalizations, savings and growth. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 10(2), 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plattner, M. (2015). Is democracy in decline? Journal of Democracy, 26, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontius, J., & McIntosh, A. (2019). Sustainability science. In Critical skills for environmental professionals. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, A. (2023). The well-being cost of inflation inequalities. Review of Income and Wealth, 70(1), 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prettner, K. (2017). A note on the implications of automation for economic growth and the labor share. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 23, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przeworski, A. (2024). Who decides what is democratic? Journal of Democracy, 35, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, L. (2021). Fairness of the distribution of public medical and health resources. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 768728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pypłacz, P., & Žukovskis, J. (2023). Implementing robotic process automation in small and medium-sized enterprises—Implications for organisations. Procedia Computer Science, 225, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W. (2023). The organizational correlates of automation depend on job status. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 13(1), 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raby, N. (2013). International transfer pricing 2013/2014: Transfer pricing at your fingertips. 900. Available online: www.pwc.com (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Raffinetti, E., Siletti, E., & Vernizzi, A. (2015). On the Gini coefficient normalization when attributes with negative values are considered. Statistical Methods & Applications, 24, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribaj, A., & Mexhuani, F. (2021). The impact of savings on economic growth in a developing country (the case of Kosovo). Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, K. (2011). Privacy in the wake of olympic security: Wikileaks sheds light on how the U.S. pressured Brazil. Electronic Frontier Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Rosário, A., & Boechat, A. C. (2025). How sustainable leadership can leverage sustainable development. Sustainability, 17(8), 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottleb, T., & Kleibert, J. M. (2022). Circulation and containment in the knowledge-based economy: Transnational education zones in Dubai and Qatar. Environment and Planning A, 54(5), 930–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubolino, E. (2023). Does weak enforcement deter tax progressivity? Journal of Public Economics, 219, 104833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüdele, K., Wolf, M., & Ramsauer, C. (2024). Synergies and trade-offs between ecological and productivity-enhancing measures in industrial production—A systematic review. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 35(6), 1315–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacher, M. (2021). Avoiding the inappropriate: The European Commission and sanctions under the stability and growth pact. Politics and Governance, 9, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarov, I., Erina, T., & Ziyatdinov, N. (2024). Economic benefits of production automation for enterprises. Ekonomika i Upravlenie: Problemy, Resheniya, 3/2(144), 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahnoun, M., & Abdennadher, C. (2020). A simultaneous-equation model of active labour market policies and change in unemployment rate: Evidence from OECD countries. Policy Studies, 43, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiful, J. A., & Setyorini, A. (2022). Ecocriticism course: Development of English pre-service teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge of sustainability. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 24, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaki, S. (2019). Equality in income and sustainability in economic growth: Agent-based simulations on OECD Data. Sustainability, 11(20), 5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, W. J. (1988). An essay on the nature and significance of the normative nature of economics. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 10(3), 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, P. A. (1958). An exact consumption-loan model of interest with or without the social contrivance of money. Journal of Political Economy, 66(6), 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, G. D., & Sharma, J. (2024). Balancing acts: Nurturing environmental sustainability for thriving economic development. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(4), 6776–6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (1999). Health in development. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 77(8), 619–623. Available online: https://consensus.app/papers/health-in-development-sen/b633ce296a4f5aecbc162fef0c5966c0/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Sen, A. (2001). Population and gender equity. Journal of Public Health Policy, 22, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (2005). Human rights and capabilities. Journal of Human Development, 6, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (2006). The argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian history, culture and identity. Foreign Affairs, 85, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (2009). Public action and the quality of life in developing countries. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 43(4), 287–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (2022). Jämställdheten och befolkningsfrågan. Tidskrift för Genusvetenskap, 22(3-4), 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senker, P. (1979). Social implications of automation. Nature, 180, 669–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, V. (2024). Managing the twin faces of AI: A commentary on “Is AI changing the world for better or worse”? Journal of Macromarketing, 44, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J., Yu, J., & Khoso, W. M. (2024). Green finance as a driver for environmental and economic resilience post-COVID-19: A focus on China’s strategy. Heliyon, 10, e35519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, O., Zolkin, A., Khabibullin, F., & Zhiltsov, S. (2025). Economic consequences of automation and robotization in industry. Ekonomika i Upravlenie: Problemy, Resheniya, 1/14(154), 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D. S., Silvestre, B. M., & Amaral, S. C. F. (2020). Assessing the timemania lottery as a sports public policy. Journal of Physical Education (Maringa), 31(1), 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemrod, J. (2019). Tax compliance and enforcement. Journal of Economic Literature, 57(4), 904–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. (1967). On the wealth of nations. South Atlantic Quarterly, 66(2), 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. (2019). Private profit, public good. In Ideals and ideologies. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. (2020). What works and what doesn’t? In Essentials of development economics (3rd ed.). University of California Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. (2019). Adam Smith: Moral and political philosophy. In Philosophy. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarin, S., Lafuente, C., Gil-Alana, L., & González-Blanch, M. J. (2024). Persistence in the unemployment and inflation relationship. Evidence from 38 OECD countries. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 16(1), 1236–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quartely Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65–94. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1884513 (accessed on 15 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Soueidan, M. H., & Shoghari, R. (2024). The impact of artificial intelligence on job loss: Risks for governments. Technium Social Sciences Journal, 57, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiel, C., Schober, B., & Strohmeier, D. (2018). Implementing intervention research into public policy—The “I3-approach”. Prevention Science, 19(3), 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing, G. (2012a). Book review response: Guy standing, the precariat: The new dangerous class. Work, Employment & Society, 26, 690–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing, G. (2012b). The precariat: From denizens to citizens? Polity, 44, 588–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing, G. (2013). Where’s howard? Global Discourse, 3, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing, G. (2014). Understanding the precariat through labour and work. Development and Change, 45, 963–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansbury, A., & Summers, L. (2017). Productivity and pay: Is the link broken? Organizations & Markets: Motivation & Incentives EJournal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, O. (2024). A note on Sen’s representation of the Gini coefficient: Revision and repercussions. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 22(4), 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. (1999). Trade and the developing world. Current History, 98(631), 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. (2009). Moving beyond market fundamentalism to a more balanced economy. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 80, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. (2012). The price of inequality. New Perspectives Quarterly, 30, 52–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, V., & Ilas, A. (2013). Explaining the underdevelopment of rural e-government: The case of Romania. In E-government implementation and practice in developing countries. IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S., Xie, Z., Yu, K., Jiang, B., Zheng, S., & Pan, X. (2021). COVID-19 and healthcare system in China: Challenges and progression for a sustainable future. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S., Krittayaruangroj, K., & Iamsawan, N. (2022). Sustainable leadership practices and competencies of SMEs for sustainability and resilience: A community-based social enterprise study. Sustainability, 14(10), 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svärd, P. (2019). The impact of new public management through outsourcing on the management of government information: The case of Sweden. Records Management Journal, 29(1–2), 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanstrom, T., Dreier, P., & Mollenkopf, J. (2002). Economic inequality and public policy: The power of place. City & Community, 1(4), 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, J., & Karlsson, R. (2018). Ecomodernist citizenship: Rethinking political obligations in a climate-changed world. Citizenship Studies, 22, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, J. (2022). Political economy of illiberal capitalism in Hungary and Poland. Politicka Ekonomie, 70(5), 617–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajane, S. S. T. S. S. (2024). Ecocriticism in literature: Examining nature and the environment in literary works. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(6), 2162–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleghani, M., & Sola, M. J. (2024). Examining the social consequences of automation and artificial intelligence in industrial management. Research in Economics and Management, 9(3), 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z., Xu, Y., Ren, J., Sun, L., & Liu, C. (2017). Inequality in the distribution of health resources and health services in China: Hospitals versus primary care institutions. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C. (2021). Provincializing Europe. In Modern social imaginaries. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R. (2023). The impact of AI and machine learning on job displacement and employment opportunities. Interantional Journal of Scientific Research in Engineering and Management, 7(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touseef, M., Siddiqui, S., & Farah, N. (2023). Understanding the role of automation in society. Pakistan Journal of Engineering, Technology & Science, 10(1), 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNU-WIDER. (2020). A snapshot of poverty and inequality in Asia: Experience over the last fifty years (WIDER Research Brief 2020/2). United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research. Available online: https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/snapshot-poverty-and-inequality-asia (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ursu, A., Childs-Disney, J., Angelbello, A., Costales, M., Meyer, S., & Disney, M. (2020). Gini coefficients as a single value metric to define chemical probe selectivity. ACS Chemical Biology, 15(8), 2031–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, B., & Kapingura, F. (2021). Understanding the nexus between savings and economic growth: A South African context. Development Southern Africa, 38, 828–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlamova, N. V. (2019). Digital rights—New generation of human rights? Proceedings of the Institute of State and Law of the RAS, 14(4), 9–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, D. (2022). Minimum wages and optimal redistribution. Available online: https://consensus.app/papers/minimum-wages-and-optimal-redistribution-vergara/66dd49a218de5983b02ad21a14077fa0/ (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Vlados, C., & Chatzinikolaou, D. (2019). Crisis, institutional innovation and change management: Thoughts from the Greek case. Journal of Economics and Political Economy, 6(1), 58–77. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3401268 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Von Hayek, F. (1933). The trend of economic thinking. Journal des Économistes et des Études Humaines, 2, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vydobora, V. (2022). Savings and investments in the theory of economic growth. Economic Scope, (177), 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y., Chou, W., Shao, Y., & Chien, T. (2020). Comparison of Ferguson’s δ and the Gini coefficient used for measuring the inequality of data related to health quality of life outcomes. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., & Lu, W. (2024). AI-induced job impact: Complementary or substitution? Empirical insights and sustainable technology considerations. Sustainable Technology and Entrepreneurship, 4(1), 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzala, R., & Obokoh, L. (2024). Savings and sustainable economic growth nexus: A South African perspective. Sustainability, 16(20), 8755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, A., Houda, M., Khan, A. M., Qureshi, A. H., & Elmazi, G. (2024). Sustainable leadership practices in construction: Building a resilient society. Environmental Challenges, 14, 100841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, A., Zakari, A., Tawiah, V., & Aleesa, N. (2024). Cultivating resilient economies through responsible mineral resource trade: Does eco-resourcing rebate matter? Resources Policy, 89, 104523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. American Educational Research Journal, 41, 237–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. (2023). Gini index. Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Wu, H., & Xu, Z. S. (2021). Fuzzy logic in decision support: Methods, applications and future trends. International Journal of Computers, Communications and Control, 16(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Yu, Z., Wei, Y. D., & Yang, L. (2019). Changing distribution of migrant population and its influencing factors in urban China: Economic transition, public policy, and amenities. Habitat International, 94, 102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R. (2025). Decoding relationship between human and environment: A Critique of ecocriticism. The Creative Launcher, 10(2), 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. (2025). AI, job displacement, and support for workers. Highlights in Business, Economics and Management, 47, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D., & Zhao, L. (2024). Exploring the relationship among public strategies and natural resource efficiency for green economic recovery. Resources Policy, 92, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagrebina, A. (2020). Concepts of democracy in democratic and nondemocratic countries. International Political Science Review, 41, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala-Alcívar, A., Verdecho, M., & Alfaro-Saíz, J. (2020). A conceptual framework to manage resilience and increase sustainability in the supply chain. Sustainability, 12(16), 6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavyalov, A. (2024). Comparative analysis of methods for measuring inequality. Ekonomika i Upravlenie: Problemy, Resheniya, 6/3(147), 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X., Yu, Y.-C., Yang, S.-Y., Lv, Y., & Sarker, M. N. I. (2022). Urban resilience for urban sustainability: Concepts, dimensions, and perspectives. Sustainability, 14(5), 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Tian, Y., & Lee, C. (2024). Enforcement actions and systemic risk. Emerging Markets Review, 59, 101115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Methodological Focus | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Quantitative Theoretical Validation | Development and mathematical simulation of EPR and EPI equations to test their internal consistency and theoretical behavior under the assumptions of the Cycle of Money theory. | To ensure the mathematical coherence and theoretical robustness of the proposed mechanisms (EPRs and EPIs). |

| Step 2 | Empirical Data Analysis | Examination of macroeconomic indicators using real-world data across countries. Key variables include debt-to-GDP ratios, global income levels, Gini coefficients (inequality), and average wages. Statistical evaluation includes descriptive trends and cross-sectional comparisons. | To demonstrate that the theory aligns with empirical patterns and to reveal the magnitude and direction of the relationships among key global indicators. |

| Step 3 | Global Policy Simulation and Implication Assessment | Application of EPR and EPI mechanisms to historical global debt data (1950–2023) in order to simulate how their implementation would impact global debt reduction. The simulation considers two scenarios: GDP-based and GDP-per-capita-based triggers. | To access potential policy implementing the proposed EPR and ΕΡΙ mechanisms on global debt trajectories and to provide actionable insights for international economic governance frameworks. |

| Countries | GDP per Capita, Current Prices (USD) | Bank Reserves as a Percentage of GDP (%) | Index of the Money Cycle (USD) | General Index of the Money Cycle (from 0 to 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | 1948.112696 | 17.92017652 | 34,910.52339 | 0.148449997 |

| Azerbaijan | 3317.379118 | 10.97020346 | 36,392.32388 | 0.153782067 |

| Egypt | 2066.01787 | 46.97299483 | 97,047.0467 | 0.326424266 |

| Ethiopia | 405.3365435 | 13.84665792 | 5612.556459 | 0.027262768 |

| Haiti | 490.0279348 | 23.12261328 | 11,330.72643 | 0.053551124 |

| Ivory Coast | 1586.736283 | 16.64475862 | 26,410.84242 | 0.116518146 |

| Albania | 2641.97687 | 50.15863333 | 132,517.9491 | 0.398221692 |

| Algeria | 3018.453435 | 34.99794 | 105,639.6522 | 0.345344978 |

| Antigua and Antigua Barbuda | 11,017.60861 | 63.81802093 | 703,121.9768 | 0.778325035 |

| Argentina | 8124.823043 | 14.323615 | 116,376.8372 | 0.367544647 |

| Armenia | 2598.006735 | 15.81307846 | 41,082.48435 | 0.1702274 |

| Aruba | 22,996.91645 | 54.10103125 | 1,244,156.896 | 0.861357987 |

| Australia | 35,040.46702 | 53.87938621 | 1,887,958.856 | 0.904101665 |

| Austria | 34,526.9247 | 62.47739286 | 2,157,152.238 | 0.915052333 |

| Afghanistan | 465.7023333 | 6.633497088 | 3089.235072 | 0.015192043 |

| Vanuatu | 1999.460174 | 84.8095122 | 169,573.242 | 0.458517221 |

| Belgium | 32,050.28565 | 54.43465357 | 1,744,646.196 | 0.897035273 |

| Venezuela | 5090.179907 | 22.77272679 | 115,917.2763 | 0.366625368 |

| Vietnam | 1492.933304 | 9.8459624 | 14,699.36518 | 0.068383222 |

| Bolivia | 1763.186087 | 22.97217483 | 40,504.21904 | 0.16823443 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 4322.342533 | 31.57276476 | 136,468.304 | 0.405281579 |

| Bulgaria | 5524.726478 | 45.68948519 | 252,421.9086 | 0.557618789 |

| Brazil | 5660.105283 | 27.81933776 | 157,460.3806 | 0.440181747 |

| France | 31,031.69072 | 52.18821786 | 1,619,488.636 | 0.889953613 |

| Yemen | 903.8433056 | 17.20925417 | 15,554.46917 | 0.072074553 |

| Germany | 32,679.55983 | 55.71401552 | 1,820,709.503 | 0.900910567 |

| Georgia | 3022.180531 | 14.77167174 | 44,642.65874 | 0.182290067 |

| Gabon | 6643.255783 | 11.51062621 | 76,468.03411 | 0.276332825 |

| Ghana | 1791.979717 | 10.80150879 | 19,356.08467 | 0.088137467 |

| Guineas | 717.4828889 | 7.294438571 | 5233.634859 | 0.025469049 |

| Guatemala | 2369.681283 | 21.31458724 | 50,508.77843 | 0.20141866 |

| Guyana | 4118.676152 | 41.30616724 | 170,126.726 | 0.459326389 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 623.6705217 | 7.710434185 | 4808.770511 | 0.023449967 |

| Grenada | 5970.487174 | 61.73021915 | 368,559.4817 | 0.64794166 |

| Denmark | 41,914.76783 | 40.32705517 | 1,690,299.155 | 0.894075387 |

| Central Africa | 412.0489348 | 5.820025179 | 2398.135175 | 0.011833614 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 820.1641176 | 9.601895652 | 7875.130275 | 0.037837284 |

| Korea (South) | 17,317.95489 | 39.70359966 | 687,585.1479 | 0.774445822 |

| Slovakia | 13,375.48412 | 49.996108 | 668,722.1487 | 0.769549696 |

| Congo | 1945.98687 | 10.7926004 | 21,002.25867 | 0.094921765 |

| Dominican Republic | 4237.6165 | 17.26588724 | 73,166.20866 | 0.267593888 |

| Hong Kong | 27,861.08207 | 241.1424815 | 6,718,490.466 | 0.971055978 |

| Ecuador | 3406.526326 | 15.32637155 | 52,209.68817 | 0.206798848 |

| El Salvador | 2318.983957 | 32.59840755 | 75,595.18411 | 0.274042996 |

| Switzerland | 55,908.56093 | 104.2269404 | 5,827,178.246 | 0.966775855 |

| Greece | 16,216.72004 | 46.64991776 | 756,508.6563 | 0.790694311 |

| Estonia | 14,819.4233 | 36.718408 | 544,145.6312 | 0.730983577 |

| Zambia | 830.7967609 | 15.94235419 | 13,244.85622 | 0.062036443 |

| Zimbabwe | 929.8230833 | 15.92128843 | 14,803.98149 | 0.068836408 |

| United Arab Emirates | 33,150.65748 | 38.40283022 | 1,273,079.071 | 0.864079586 |

| United States | 40,588.94259 | 65.33068966 | 2,651,703.612 | 0.929782899 |

| United Kingdom | 31,229.44409 | 126.56 | 3,952,398.444 | 0.951776304 |

| Jamaica | 3689.156913 | 33.97675439 | 125,345.5783 | 0.384965699 |

| Japan | 33,406.88363 | 149.782981 | 5,003,782.617 | 0.96151905 |

| India | 969.7367174 | 32.68084655 | 31,691.81686 | 0.136633179 |

| Indonesia | 2109.498391 | 28.24749868 | 59,588.05303 | 0.229322047 |

| Jordan | 2758.345 | 67.06397885 | 184,985.5907 | 0.480180286 |

| Iraq | 4560.155043 | 12.59950621 | 57,455.70177 | 0.222945333 |

| Iran | 4844.393152 | 32.34295385 | 156,681.9841 | 0.438960919 |

| Ireland | 41,540.2963 | 56.59063276 | 2,350,791.653 | 0.921500356 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 6565.050522 | 7.425165313 | 48,746.58541 | 0.195767102 |

| Iceland | 39,893.77643 | 40.24109298 | 1,605,369.167 | 0.889093083 |

| Spain | 20,721.4172 | 65.74816724 | 1,362,395.203 | 0.87184836 |

| Israel | 24,128.48048 | 51.3453069 | 1,238,884.235 | 0.860850036 |

| Italy | 25,693.1288 | 57.18511897 | 1,469,264.627 | 0.880051606 |

| Cape Verde | 2173.423826 | 36.52810951 | 79,391.06354 | 0.283896995 |

| Kazakhstan | 6457.822529 | 18.2279012 | 117,712.551 | 0.370201445 |

| Cameroon | 1188.564435 | 11.44988414 | 13,608.92507 | 0.063633165 |

| Cambodia | 762.49265 | 23.1891624 | 17,681.56589 | 0.081131201 |

| Canada | 32,119.78235 | 66.3011898 | 2,129,579.786 | 0.914047019 |

| Qatar | 41,906.77233 | 40.10925034 | 1,680,849.222 | 0.893543263 |

| Kenya | 991.4103478 | 21.88609649 | 21,698.10253 | 0.097759253 |

| China | 4024.179978 | 40.88628182 | 164,533.7567 | 0.45103677 |

| Colombia | 3924.512348 | 16.72194429 | 65,625.47683 | 0.246821961 |

| Comoros | 1026.33563 | 12.32517543 | 12,649.76669 | 0.059414761 |

| Kosovo | 3568.725115 | 37.04882222 | 132,217.0624 | 0.397677086 |

| Costa Rica | 6112.665304 | 21.47514828 | 131,270.3938 | 0.395957164 |

| Kuwait | 21,791.50291 | 58.89016545 | 1,283,305.212 | 0.865016481 |

| Croatia | 11,166.31776 | 48.78632917 | 544,763.654 | 0.731206736 |

| Cyprus | 19,570.18613 | 96.38547321 | 1,886,281.651 | 0.90402458 |

| Laos | 1176.850652 | 10.07284625 | 11,854.23568 | 0.055887051 |

| Lesotho | 737.812587 | 25.16656642 | 18,568.20947 | 0.084854317 |

| Latvia | 11,160.42656 | 27.780044 | 310,037.1409 | 0.607566311 |

| Belarus | 4376.290912 | 18.03565875 | 78,929.28948 | 0.282712558 |

| Lebanon | 4216.301 | 155.7440213 | 656,663.6727 | 0.766306827 |

| Liberia | 572.9561538 | 114.8022563 | 65,776.65925 | 0.247249981 |

| Libya | 7315.118935 | 34.80366514 | 254,592.9498 | 0.559730318 |

| Lithuania | 12,884.44706 | 26.58728 | 342,562.4017 | 0.63108062 |

| Luxembourg | 71,771.91498 | 203.1265164 | 14,578,779.06 | 0.986449971 |

| Madagascar | 428.1648043 | 12.05560143 | 5161.784227 | 0.02512818 |

| Macau | 55,512.1606 | 117.5139441 | 6,523,452.939 | 0.970216386 |

| Malaysia | 6476.299 | 74.66777414 | 483,570.831 | 0.707153556 |

| Malawi | 321.7748696 | 9.875763077 | 3177.772376 | 0.015620645 |

| Maldives | 6137.711391 | 22.22559585 | 136,414.2928 | 0.40518617 |

| Mali | 556.6702826 | 9.735537931 | 5419.484651 | 0.026349641 |

| Malta | 16,371.22865 | 98.15051207 | 1,606,844.475 | 0.889183626 |

| Morocco | 2105.063565 | 39.36468793 | 82,865.17032 | 0.292684099 |

| Mauritius | 5798.680261 | 53.04348276 | 307,582.1964 | 0.605669246 |

| Mauritania | 1358.574611 | 10.41531156 | 14,149.97785 | 0.06599608 |

| Montenegro | 6659.721231 | 39.35027333 | 262,061.8508 | 0.566843018 |

| Mexico | 6753.711522 | 20.36038052 | 137,508.1365 | 0.407112462 |

| Myanmar | 884.0053571 | 10.40086453 | 9194.419962 | 0.043897759 |

| Micronesia | 2971.332645 | 45.15800909 | 134,179.4666 | 0.401211399 |

| Mongolia | 2353.007111 | 24.12824222 | 56,773.92553 | 0.220884185 |

| Mozambique | 378.8300217 | 64.12319 | 24,291.78946 | 0.108180759 |

| Moldova | 2293.259265 | 26.10301111 | 59,860.97207 | 0.230130654 |

| Bangladesh | 816.0283111 | 25.55551703 | 20,854.0254 | 0.094314997 |

| Barbados | 12,250.47987 | 59.274732 | 726,143.9111 | 0.78383387 |

| Bahrain | 16,931.04087 | 52.90511579 | 895,738.6776 | 0.817283515 |

| Belize | 3261.128261 | 44.75982857 | 145,967.5419 | 0.421598684 |

| Benin | 841.8228913 | 13.95752741 | 11,749.76608 | 0.055421823 |

| Botswana | 4544.127109 | 24.6508913 | 112,016.7834 | 0.358714111 |

| Burkina Faso | 507.6985652 | 11.04747155 | 5608.785456 | 0.027244949 |

| Burundi | 214.7511522 | 10.32790037 | 2217.928504 | 0.010954124 |

| Bhutan | 1583.612457 | 35.96195588 | 56,949.8013 | 0.221416939 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 25,530.34 | 60.16403158 | 1,536,008.182 | 0.884662529 |

| Togo | 509.9262826 | 21.44249509 | 10,934.09181 | 0.051773608 |

| Namibia | 3719.805568 | 40.153725 | 149,364.0498 | 0.427217762 |

| New Zealand | 24,730.92985 | 51.30157857 | 1,268,735.741 | 0.863677714 |

| Nepal | 500.352413 | 25.56723448 | 12,792.62747 | 0.060045474 |

| Solomon Islands | 1437.595826 | 23.30498462 | 33,503.14861 | 0.143323147 |

| Niger | 424.9241957 | 8.325938704 | 3537.892807 | 0.01736012 |

| Nigeria | 1747.902889 | 11.9169569 | 20,829.68339 | 0.094215279 |

| Nicaragua | 1488.527313 | 17.32443914 | 25,787.90083 | 0.114083413 |

| Norway | 53,856.5135 | 45.46127931 | 2,448,386.003 | 0.924392827 |

| South Africa | 4432.883065 | 50.76933269 | 225,054.5151 | 0.529152974 |

| South Sudan | 663.147 | 11.71342167 | 7767.720438 | 0.037340487 |

| Congo | 709.075587 | 4.891744529 | 3468.616623 | 0.017025976 |

| Dominica | 5206.765311 | 55.0462 | 286,612.6447 | 0.588685336 |

| Netherlands | 36,325.13478 | 65.76054464 | 2,388,760.648 | 0.922651585 |

| Oman | 11,502.13563 | 24.75447913 | 284,729.3764 | 0.587088143 |

| Honduras | 1591.371043 | 23.3126519 | 37,099.07917 | 0.156301785 |

| Hungary | 9197.030696 | 37.41676944 | 344,123.1771 | 0.632138339 |

| Uganda | 667.6110435 | 9.087937241 | 6067.207265 | 0.029406273 |

| Ukraine | 2385.365941 | 22.49849615 | 53,667.14645 | 0.211351627 |

| Uruguay | 8846.045239 | 27.06401862 | 239,409.5331 | 0.54452605 |

| Pakistan | 785.969275 | 23.0577 | 18,122.64375 | 0.082987116 |

| Panama | 7155.365457 | 42.26210121 | 302,400.7791 | 0.601604463 |