Abstract

Digital skills are increasingly vital for enhancing employability, as they equip individuals to meet the evolving demands of the modern workforce. Therefore, this paper examines the impact of digital skills on employability, focusing on the influence of both basic and above-basic levels of information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, problem-solving, digital content creation, and safety skills, considered key components of digital competence. The research employs regression analysis using secondary data extracted from the Eurostat database. Based on data from 32 European countries, the findings indicate that three proxies for digital skills, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, and safety, significantly and positively influence employability. The contribution of this paper to the existing literature on digital skills and employability is twofold. First, by evaluating the influence of five categories of digital skills across different proficiency levels on employment rates, the study sheds light on which specific digital skills have the most substantial impact on employability in today’s labor market. Second, the findings provide a foundation for formulating recommendations aimed at enhancing the digital capabilities of the labor force.

1. Introduction

Digital technology has entered and changed irretrievably the way of living and performing the jobs of the majority of people from all around the world (Kaczorowska-Spychalska, 2018; Tutar & Turhan, 2023). This technology changed the ways people communicate, pay bills, plan holidays, or seek jobs (Good Things Foundation, 2019; Polyakova et al., 2024). It has also reshaped the ways employees perform activities within their job duties (Charles et al., 2022) and caused the appearance of many new jobs (Hooley & Staunton, 2020). The trend of the influence of this technology on everyday activities and the world of work will continue in the future in even more progressive rates and unpredictable ways (Good Things Foundation, 2019).

What recently gave a specifically strong impulse for the intensive use of digital technology by people all over the world was the COVID-19 pandemic (Vărzaru & Bocean, 2024). Due to the “lockdown” that was announced in many countries, people of different ages and educational backgrounds from all around the world, to accomplish their everyday activities or work duties, “were put” into the digital world. Many of them had to acquire digital skills for the first time or to enhance existing ones.

When it is about the area of employment, which is in focus in this paper, in today’s digital business landscape, most of the jobs require some level of digital skills. The digital skills of employees even became one of the basic components of their competitiveness in the labor market and their employability (Gonzalez Vazquez et al., 2019; van Laar et al., 2019).

However, employability is not a concept that has been exclusively connected with digital skills, nor did it emerge in the post-pandemic period. This concept had its origin at the beginning of the 20th century, and during that time was used in several contexts and with a wide range of meanings. Today, this concept is still actual and even gains more importance as it becomes the key mechanism for gaining, maintaining, or obtaining employment.

Having in mind the fact that today’s business environment is digitalized and that most jobs require a certain level of using digital technology, it appears that possessing digital skills is of high importance for persons’ employment (European Commission, 2022). Based on this premise, the paper aims to investigate how distinct digital skill sets, especially at basic and above-basic levels, influence employment outcomes in 32 European countries. Digital skills whose influence on employability will be investigated are selected based on the European Commission framework for digital skills, as well as the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) (European Commission, 2023, 2024a). These skills include skills such as information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, problem-solving, digital content creation, and digital safety at both basic and advanced levels of their development. Employability in this paper will be measured by the employment rate. The findings aim to support policy and educational strategies that foster targeted digital upskilling to enhance workforce readiness in an evolving labor market.

The paper is structured as follows. After the introduction, in the second part of the paper, the theoretical background on digital skills and employability will be given. Afterwards, this part will also address hypothesis development. The third part will present the data and methodology of the research, the fourth the results, and the fifth their discussion. Concluding remarks are given at the end of the paper, along with the contribution of the paper.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Digital Skills

Definitions of what digital skills are started to appear after Gilster (1997). At the end of the 1990s, he defined digital literacy as “the ability to understand and use information in multiple formats from a wide range of sources when it is presented via computers” (Gilster, 1997, p. 1). Since then, many definitions of digital skills have emerged, as well as many terms for representing them. The most known are “digital literacy”, “digital skills”, digital competencies”, and “digital thinking” (Tinmaz et al., 2022).

One of the broadly accepted definitions of digital skills is UNESCO’s definition, according to which digital skills represent the range of abilities to use digital devices, communication applications, and networks to access and manage information (UNESCO, 2018). However, many authors, when defining digital skills, have more operational focus and define digital skills in terms of their content. In that line, van Laar et al. (2020) define digital skills as technical, information, communication, collaboration, critical thinking, creative, and problem-solving digital skills.

The United Kingdom (UK) has established a framework with five essential digital skills necessary for life and work. According to this framework, foundational digital skills are using devices and handling information, creating and editing, communicating, conducting transactions, and being safe and responsible online (UK GOV, 2019). Similarly, ITU (2023) on an international level identifies five types of digital skills, such as communication/collaboration, problem-solving, safety, content creation, and information/data literacy.

One of the most comprehensive views on digital skills is the European Commission framework, upon which digital skills are also divided into five categories. These skills include information and data literacy, communications and collaboration, digital content creation (including programming), safety (including digital well-being and competencies related to cybersecurity), and problem-solving (Vuorikari et al., 2022).

When it comes to the level of development of digital skills, there are also different approaches. According to the ITU (2018), digital skills can be general, domain-specific, and advanced. DigComp indicates that the proficiency level of every digital skills category ranges from foundation level, through intermediate and advanced, to highly specialized levels of proficiency (Vuorikari et al., 2022). At the European Union level (European Commission, 2023, 2024a), digital skills’ components can have a basic or above-basic level (European Commission, 2024a, 2025).

In this study, digital skills will be observed as a five-component category upon the European Commission framework for digital skills, as well as the DESI framework (European Commission, 2024a), with two levels of development: basic and above-basic levels. These skills will be analyzed in the context of influencing the employability of individuals in the contemporary labor market.

2.2. Employability

The concept of employability has a long history that traces back to the beginning of the 20th century (Cheng et al., 2022; Gazier, 2001; McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005). During that time, this concept was used with different meanings (McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005) and from different perspectives (Nauta et al., 2009).

According to Gazier (2001), the concept of employability emerged at the beginning of the 20th century in the UK and the United States of America (USA) and has seven operational meanings. According to this author, the evolution of the concept of employability started with the dichotomic meaning as it was seen in the context of differences between those who are “employable” and those who are “unemployable”. The second meaning of employability was socio-medical. According to this meaning, employability was seen as a useful concept for explaining the difference between the existing work abilities of vulnerable groups of people (socially, physically, or mentally disadvantaged people) and the work requirements of employment. The third meaning of employability was manpower policy. This view on employability was the extension of the socio-medical view as it included considering the employability of additional vulnerable groups of people. According to Gazier (2001), flow employability was the fourth meaning of employability and had a focus on the accessibility of employment within local and national economies. The next meaning of employability was labor market performance employability. From this point of view, employability was seen as a framework for explaining the labor market outcomes achieved by policy interventions. When it is about the sixth meaning, known as initiative employability, the emphasis was put on individuals as a key driver of employability. Upon this meaning of employability to build a successful career employees should develop transferable skills and the flexibility to provide them successful moving between job roles (McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005). When it is about the seventh meaning, interactive employability, it maintained the emphasis on individual initiative, but the employability of the individuals was also assessed relative to the employability but also acknowledged the influence of the institutions and labor market as well Gazier (2001).

According to this historical view on employability, three key subjects that generate the employability of an individual could be identified: governments, organizations, and individuals themselves. Therefore, some authors distinguish three perspectives on employability, such as (a) socio-economical, (b) organizational perspective, and (c) individual perspective (Nauta et al., 2009).

When it comes to the determinants of employability, several approaches also emerged. These approaches are economic, sociological, psychological, managerial, and systemic frameworks (Ouedraogo, 2024). In the opinion of Ouedraogo (2024), from the economic perspective, the main determinants of employability are the human capital of the individual, the regulation and the segmentation of the labor market, the information, and the dynamism of economic activity. When it is about a sociological perspective, the main determinant of employability is the social capital of individuals. From a psychological perspective, the main drivers of employability are motivation, willingness, goal pursuit, self-confidence, and the skills of individuals. Following the management approach, Ouedraogo (2024) states that, from this perspective, the employers are key subjects of employees’ employability as employers by enhancing employees’ competencies, flexibility, and adaptability to meet new technological development requirements of the working environment at the same time as enhancing their employability. However, as the employability of individuals is a complex phenomenon, a new, comprehensive, global, integrated, and dynamic approach is proposed (Ouedraogo, 2024), which includes all previous approaches.

The concept of employability is still evolving and constantly includes many additional determinants. In the contemporary digitalized ambience, the employability of individuals includes not only their core competencies (hard skills) but also many soft skills such as digital skills, communication, teamwork, problem-solving, personal branding, resilience, etc.

In this paper, the individual perspective on employability will be adopted, as the determinants of this construct that will be analyzed are an individual’s digital skills.

2.3. Hypothesis Development

Many researchers regarding the importance of digital skills for employability have been conducted so far. It has been found that digital skills are a prerequisite for employability (Kee et al., 2023; Smaldone et al., 2022), provide better labor market indicators (Başol & Yalçin, 2021) and higher academic achievement, as well as competitiveness in the labor market, and enhance health and civic and political engagement (Tinmaz et al., 2022). Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that individual components of digital skills according to the European Commission and DESI framework can also have a positive influence on employability. This will be more precisely elaborated in the following text.

When it is about information literacy, as a component of digital skills, it refers to people’s ability to obtain, assess, and evaluate information by using digital devices (Mackey & Jacobson, 2011). These skills are of high importance for today’s digitalized landscape as they equip individuals with the skills needed to adapt to new (informational) technologies and make informed decisions (Nikou et al., 2022). It was also found that information literacy equips the graduates for a better employment perspective as it provides better aligning of their competencies with employer expectations (Goldstein, 2016). On the other hand, data literacy as a skill refers to a person’s ability to understand the data, being able to read data, and being able to create them (Pangrazio & Sefton-Green, 2020). Taken together, information literacy, as well as data literacy, enables individuals easily to adapt to new technologies and to successfully manage digital data, which are necessary for companies functioning. In that line is also the fact that developing these skills became part of workforce development strategies for many companies (World Economic Forum, 2023). Based on the previous text, it could be concluded that employees who possess such information and data literacy are highly valuable for employers regardless of the sector they belong to. Therefore, the first hypothesis that is going to be tested in the paper is as follows:

H1.

Information and data literacy skills have a positive influence on the employability of the workforce.

In today’s digitalized landscape, a significant level of everyday and business communication relies on using electronic devices and digital technologies. Thanks to different digital tools and devices, individuals and organizations can interact with each other in real time or exchange messages by using different digital communication platforms. In the world of work, many benefits of digital communication and collaboration have been identified so far. It has been found that digital communication in the virtual workforce has a positive influence on company performance as it reduces expenses (Lin & Roan, 2022). It has been also found that employers may increase profit due to remote labor since it enables lower overhead expenses (Battisti et al., 2022). Digital communication can also enhance effective coordination among organizational members, enhance decision-making, overcome geographical barriers, increase organizational member involvement, etc. In other words, digital communication become a tool for improving organizational performance (Harjono, 2023). As organizations rely significantly on digital tools, there is a growing need for employees who possess digital communication skills, as well as knowledge of using different electronic devices and digital technologies, for such communication. In addition, employees who possess highly developed collaborative skills for virtual workplaces are also highly valued. These skills also enable employees to meet demands for digital communication in different industries. In other words, possessing such transferable skills enables employees to be intra- and inter-sectoral mobile and, hence, to have better job prospects (Hashim & Turiman, 2024). Based on the above, the second hypothesis that is going to be tested in this paper is as follows:

H2.

Communication and collaboration skills have a positive influence on the employability of the workforce.

When digital content creation skill is discussed, it refers to the ability to “digital content creation skills refer to the ability to create and edit various types of digital materials—such as text documents, images, and videos. These skills also include the ability to integrate and adapt existing content or knowledge, produce creative works like media projects or software, and understand how to apply intellectual property rights and licenses appropriately” (Kee et al., 2023, p. 3). As organizations should constantly adapt to the evolving digital landscape (today is almost necessary for companies to create and manage digital content in different digital media), there is a growing need for employees who can produce high-quality digital content that will correspond with the target audience’s needs (World Economic Forum, 2023). Therefore it is reasonable to believe that digital content creation skills are of high value among employers, which in turn may enable employees to have better job prospects (Hashim & Turiman, 2024). In that line is the research of some authors who found that digital skills, including digital content creation, have a significant and positive relationship with perceived employability among youth (Kee et al., 2023). Therefore, the third hypothesis that is going to be tested in this paper is as follows:

H3.

Digital content creation skills have a positive influence on the employability of the workforce.

In today’s digitalized landscape, digital safety skills are also of high importance as they are a prerequisite for cyber-security behavior (Dodel & Mesch, 2018) and are highly important for such contests. These skills also include “the ability to install and update antivirus software, configure mobile security, utilize an anonymous browser, clear browsing history and cookies, and recognize executable files” (Dodel & Mesch, 2018, p. 717). Digital safety skills are particularly important to be possessed by employees who work in companies that highly depend on digital technology and where security is of significant importance, such as finance, insurance, healthcare, and technology etc. Companies from these sectors usually put high emphasis on cybersecurity training of their employees, equipping them with these necessary digital safety skills. As these skills are, in most cases, transferable, it is reasonable to believe that they could be implemented in different industries and, hence, enhance the career prospects of the individuals; in other words, to boost their employability. Regarding the importance of digital safety skills for the employability of individuals, some authors concluded that possessing strong digital safety skills can significantly improve job prospects, especially in roles that require handling sensitive information and maintaining cybersecurity (Pirzada & Khan, 2013). Based on the previous text, the fourth hypothesis that is going to be tested in the paper is as follows:

H4.

Digital safety skills have a positive influence on the employability of the workforce.

Lastly, workers should possess the critical thinking, holistic thinking, data collection, and analysis skills necessary to support supervisors or themselves in making decisions (Chen et al., 2018). These skills are united under the name “problem-solving skills”. Besides teamwork and communication skills, the third identified group of skills desirable to be manifested by an employee is problem-solving skills (Burrus et al., 2013). Problem-solving skills are also the most wanted skills from the point of the employer in the phase when a person is just entering the labor market and searching for a job (Jewell et al., 2020; Smaldone et al., 2022), as it enables individuals to navigate complex challenges, think critically, and develop innovative solutions. Possessing these skills makes employees highly valuable to employers and can significantly enhance their job prospects and career success (Alrifai & Raju, 2019). Based on the above, the fifth hypothesis that is going to be tested in the paper is as follows:

H5.

Problem-solving skills have a positive influence on the employability of the workforce.

3. Methodology

To test the proposed hypothesis, data are derived from the publicly available Eurostat database (European Commission, 2025). A cross-sectional comparison is done based on the dataset for 2023. The reason for such an analysis is anchored in the Digital Decade policy program 2030, which set principles of digital transformation in terms of digital skills until 2030 (European Commission, 2022). The analysis is made in a cross-sectional manner to test the influence of digital skills indicators on the employment rate as a proxy of workforce employability. Even though the employment rate is criticized as an indicator of institutional achievement rather than individual success in obtaining and retaining a job, many educational institutions still use it to assess their accomplishments in the educational process as a reliable indicator (Harvey, 2001). Indicators of the level of digital skills development achieved are based on the renewed DESI methodology (European Commission, 2024b). Precisely, as DESI measures digital skills, it assesses individuals that have at least basic digital skills or above basic digital skills. The assessment in this paper is based on the 2023 data, and it could be also analyzed from the point of view of five separate datasets that make digital skills aggregate measures as follows: information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, problem-solving, digital content creation, and safety (European Commission, 2024a). Table 1 presents the variables used in the research and their data source.

Table 1.

Research variables and their data sources.

The analysis was conducted using multiple regression analysis. The computation was done using Stata software version 15.0. In this analysis, five models are tested. In every model, the employment rate is the dependent variable, while in the first model, independent variables are levels of information and data literacy skills; in the second model, levels of communication and collaboration skills; in the third model, levels of digital content creation; in the fourth model, levels of safety skills; and the fifth model, levels of problem-solving skills.

Furthermore, the dataset for the analysis is made up of 27 EU countries with the addition of Norway, Switzerland, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Turkey, and it is based on the contemporary available datasets provided by Eurostat. Thus, the sample consists of 32 observations and allows for the proposed analysis to be conducted. The descriptive statistics of the sample are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 2 indicates that the employment rate in the selected countries has a mean value of 70.925 per cent, and it ranges between 51.80 per cent in Bosnia and Herzegovina and 82.40 per cent in the Netherlands. Additionally, the mean values of the basic and above-basic levels of the five digital skills’ dimensions are vastly different, but when the safety skills and problem-solving skills are observed, that difference is greater than noted in the other three skills’ categories.

4. Results

The prior step to conducting multiple regression analysis, which is a parametric method, is to test whether the assumptions of that analysis are met. Therefore, it tested the normality, linearity, multicollinearity, and homoscedasticity of the dataset. Table 3 presents the results of the assumptions’ testing.

Table 3.

Multiple regression analysis’s assumptions testing.

The normality of the data is proposed according to the central limit theorem if the size of the sample is greater than 30 observations. According to the central limit theorem, as the sample size becomes larger, the distribution of the sample means tends to resemble a normal distribution, even if the original population distribution is not normal (Cleff, 2019, p. 227). Multicollinearity is assessed by the variance inflation index calculation. The cut-off point for VIF is 10 (Field, 2018). Therefore, the first and fifth models do not meet the requirements for a parametric test. The regression models for information and data literacy and problem-solving skills were excluded due to high multicollinearity (VIF > 10), which violates key assumptions of multiple regression and compromises result validity. This overlap suggests a convergence in skill measurement, possibly due to limitations in how proficiency levels are captured. While their exclusion narrows the analytical scope, it ensures the statistical robustness of the remaining models. Lastly, all models, besides the fifth, do not manifest the problem of heteroskedasticity according to Breusch-Pagan test, while no heteroskedasticity was identified according to the White test (Table 3).

Moreover, correlation analysis was conducted to present the relationship between dependent and independent variables. The results of the correlation analysis are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlation analysis results.

Table 4 presents that between the employment rate and the basic categories of digital skills, i.e., the information and data literacy skills (r = −0.310, p > 0.05), the communication and collaboration skills (r = −0.013, p > 0.05), the digital content creation skills (r = −0.428, p < 0.01), the safety skills (r = −0.364, p < 0.05), and the problem-solving skills (r = −0.592, p < 0.01), there is a negative relationship. Moreover, three correlation coefficients are statistically significant, between the employment rate, on one side, and digital content creation, safety skills, and problem-solving skills, on the other side. On the other hand, between the employment rate and the above-basic categories of digital skills, i.e., the information and data literacy skills (r = 0.365, p < 0.05), the communication and collaboration skills (r = 0.208, p > 0.05), the digital content creation (r = 0.554, p > 0.01), the safety skills (r = 0.596, p < 0.01), and the problem-solving skills (r = 0.599, p < 0.01), there is a positive relationship. That relationship is significant in four of five models since it is not significant between the employment rate and the communication and collaboration skills. The results point out that greater employability of the workforce above the basic level of digital skills is required. It is not even desirable that the worker has only a basic level of digital skills because it is negatively related to their employability.

Bearing in mind previously tested relationships, it is reasonable to expect that a higher level of digital skills would have a positive effect on the employment rate, while the basic digital skills level has a negative or no effect on the employment rate. Therefore, the research models that are going to be tested using multiple linear regression analysis are as follows:

where β0 is intercept, β1–β2 are parameters connected with independent variables and ε is an error term.

Empl_rate = β0 + β1 Info_data_basic_literacy + β2 Info_data_above_literacy + ε

Empl_rate = β0 + β1 Comm_coll_basic_skills + β2 Comm_coll_above_skills + ε

Empl_rate = β0 + β1 Digi_con_basic_skills + β2 Digi_con_above_skills + ε

Empl_rate = β0 + β1 Safety_basic_skills + β2 Safety_above_skills + ε

Empl_rate = β0 + β1 Prob_sol_basic_skills + β2 Prob_sol_above_skills + ε

Due to multicollinearity issues, the proposed first and fifth models will be omitted from the analysis because, in the first and fifth models, multicollinearity was identified, while in the fifth model, heteroskedasticity might be also an issue. Keeping in mind the relatively small and diverse sample size, Table 5 presents the obtained data from the multiple regression analysis with robust standard errors to address potential heteroskedasticity in the cross-sectional data that was not previously captured by Breusch-Pagan and the White test.

Table 5.

Multiple regression analysis results.

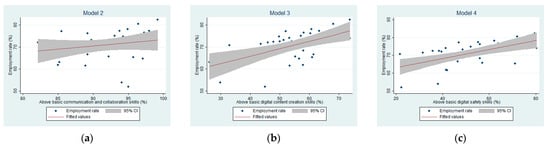

In Table 5, the results of three regression models are presented. Moreover, Figure 1 gives visualisation of the obtained results. Models 2, 3, and 4 are statistically significant, and their regression coefficients are additionally examined.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of regression results showing the relationship between digital skills and employment rate in 32 European countries: (a) Communication and collaboration skills; (b) Digital content creation skills; and (c) Digital safety skills. The plots include regression lines with 95% confidence intervals to illustrate the strength and direction of the associations.

In the second model, the F-statistic is significant (F = 4.53, p < 0.05), indicating that the model is statistically significant at the 5 per cent level. The model explains 18.2 per cent of the employment rate variability. The regression coefficient for the communication and collaboration skills at the basic level is positive and significant at the 5 per cent level (β1 = 1.645, p < 0.05), while the regression coefficient for the communication and collaboration skills above the basic level is also positive and statistically significant (β2 = 1.305, p < 0.01) (Figure 1a). Finally, the influence of the communication and collaboration skills’ levels on the employment rate of the observed sample is positive. Thus, the second hypothesis is confirmed.

The third research model is also statistically significant (F = 6.81, p < 0.01). This model explains 34.5 per cent of dependent variables’ variations. On the other hand, the regression coefficients for the variable “the basic digital content creation skills” have a negative sign but are not statistically significant (β1 = −0.296, p > 0.05). The above-basic level of digital content creation skills has a positive and statistically insignificant influence on the employment rate (β2 = 0.278, p < 0.01) (Figure 1b). Therefore, the model can be observed as significant but with constraints in terms of regression coefficients significance since only the variable “the above basic digital content creation skills” has a positive influence on the employment rate. Thus, the third hypothesis is partially confirmed.

Lastly, the fourth model is statistically significant at the level of 0.1 per cent (F = 9.68, p < 0.001). The coefficient of determination implies that 41.9 per cent of variations in the dependent variable, i.e., the employment rate, are explained by the variations in both levels of digital safety skills. Precisely, the basic level of safety skills has a positive influence but is not significant (β1 = 0.539, p > 0.05), while the safety skills above the basic level have a positive influence at the 0.1 per cent level of significance (β2 = 0.421, p < 0.001) on the employment rate (Figure 1c). Consequently, the fourth hypothesis is partially confirmed.

5. Discussion

In the contemporary context, digital skills are observed as a necessary precondition of a person’s employment status. Even though there are different approaches to digital skills, their components, or proficiency levels, there is no doubt that these skills are an essential asset in today’s labour market conditions. Their importance is growing rapidly, and it is foreseen that the trend will continue in the forthcoming years (World Economic Forum, 2023).

It is proven that digital skills are necessary for almost all occupations, from primary occupations to managerial positions (Curtarelli et al., 2017). In some cases, such as in Gulf Cooperation Council countries, digitalization tends to negatively impact employment in traditional industries but might offer opportunities for new job creation in high-skilled areas if accompanied by targeted skill development (Bousrih et al., 2022). Consequently, there is an importance of studying artificial intelligence (AI) technologies and their effects on employment—specifically, how AI might replace or supplement human labour. While AI is still in its early and experimental stages, its expected growth calls for careful consideration of how it will affect the job market. Furthermore, both theoretical and empirical research suggests that people with greater skill levels are more likely to have complementary skills to digital and AI technologies, which leads to positive employment and salary results. Conversely, workers with lesser levels of expertise are typically more susceptible to being replaced. The complex and multidimensional interaction between AI and job dynamics highlights the AI’s ability to create new tasks and occupational categories that could lessen some of the negative effects of automation (Aum & Shin, 2025; Richiardi et al., 2025). Therefore, contemporary skill sets such as digital skills are a necessity for enhancing the workforce’s employability. The concept of employability stresses the importance of a person’s skills, attitudes, behaviour, etc., for their employment status, no matter the perspective of their observation.

This research’s findings offer proof that some components of digital skills observed through the lenses of DESI indicators influence employment rates as a proxy for employability. Specifically, digital skills categories such as communication and collaboration skills, digital content creation skills, and safety skills positively influence the employment rate of the workforce. Moreover, the study results imply that all three categories of digital skills have a significant positive influence on the employment rate if their level is above basic, while basic levels of communication and collaboration skills has also a strong influence on persons’ employability. On the other hand, the influence of information and data literacy and problem-solving skills on the employment rate could not be tested because models did not meet the conditions for further analysis.

The results of the study are in line with several research studies previously conducted. The results indicate that the higher the basic and above-basic communication and collaboration skills, the better the employability of the workforce. Their relationship with perceived employability (Kee et al., 2023) and GDP per capita (Tran et al., 2023) was also found to be significantly positive. Nevertheless, the communication and collaboration skills of employees are in demand in all companies where collaborative, remote, and virtual work environments stand out (Lin & Roan, 2022). Since employers are emphasizing the upskilling and reskilling of the workforce to become collaborative team players and to effectively communicate with stakeholders (World Economic Forum, 2023), educational institutions have a central role in building these skills. An emergency such as the COVID-19 pandemic catalysed significant advancements in digital communication within higher education contexts. Communication and collaboration skills training can be incorporated both in subjects that build hard skills or in courses for soft skills development (Schulz, 2008). Courses that enhance communication and collaboration skills will create a ready-for-the-labour market workforce and thus increase their employability potential.

The positive influence of the above basic digital content creation skills on the employment rate was also found in this research. Similarly, the research of Hashim and Turiman (2024) through focus groups showed that respondents perceive their digital content creation skills’ development will meet labour market requirements and that it will increase their likelihood of finding a job. What is more, digital content creation proficiency encompasses not only creativity but also a blend of technological literacy, marketing expertise, and an understanding of the user experience. This diverse skill set is essential for generating high-quality content that aligns with organizational objectives (World Economic Forum, 2023). Since organizations prioritize employees with the capability of producing engaging content that effectively connects with target audiences and aligns with their comprehensive business strategies, future employees should track and follow the progress in modern tool development and, thus, upskill following the advancement. The study of Dangprasert (2023) found that a learning activity model significantly enhanced graduate students’ digital content creation and technology skills, with a strong correlation between the two. Keys to this success were interactive, hands-on methods such as flipped classrooms, project-based learning, and online mentorship, which boosted digital content creation skills, as well as other soft skills (i.e., problem-solving and critical thinking).

Both positive influences of basic and above-basic digital safety skills were found in this study. What is more, the higher the level of safety skills, the more probable it will be for the person to have a job. Moreover, the country’s GDP per capita (Tran et al., 2023) and national security (Dodel & Mesch, 2018) are also positively related to the level of digital safety skills. It was found by Kee et al. (2023) that these skills’ influence on perceived employability can be transmitted through the course content, thus implying that educational organizations must put an effort into educating future and current employees on how to perform work in a digitally safe manner. The study of Dodel and Mesch (2018) stressed that education level positively influences the digital security skills of employees. An employee who did not learn how to perform work safely is a threat to the organization and its employment status. Besides technology, advanced digital safety skills are a requirement for protective antivirus behaviour (Dodel & Mesch, 2018). This suggests that workers need to develop higher proficiency in digital security to remain relevant and competitive in the evolving job market.

6. Conclusions

This study provides strong evidence that digital skills, particularly communication and collaboration, digital content creation, and digital safety, play a significant role in enhancing employability across European countries. The findings show that not all digital skills are equally influential, and that above-basic proficiency levels are especially critical for positive employment outcomes in today’s digital economy.

By focusing on individual digital competencies rather than aggregated indices, this research offers refined insights into which skills truly matter in the labour market. It reinforces the strategic importance of fostering advanced digital capabilities, not only as a personal advantage for job seekers but also as a broader imperative for education systems, employers, and policymakers. Importantly, the findings align with the goals of the EU’s Digital Decade Policy Programme 2030, underlining the need to prioritize skills development in areas that yield the greatest impact on workforce participation. This has direct implications for curriculum design, training programs, and digital upskilling initiatives, especially those aimed at boosting competitiveness in an evolving job landscape shaped by remote work, digital platforms, and cybersecurity demands.

This study is not without limitations. First, the impact of digital skill categories on the employment rate had to be analysed separately because the model assessing their combined influence lacked statistical significance. This might suggest that digital skills, as a whole, do not affect employment, a likely misleading interpretation. To address these limitations, future research should consider collecting primary data, such as employee surveys, to allow for the analysis of all digital skill categories within a single, comprehensive model. Second, the analysis relies on data from a single year, as available datasets are limited to 2 non-consecutive years. While a longitudinal approach would offer more robust insights, this study still provides a valuable snapshot of how digital skills currently relate to employability. Thirdly, the key macroeconomic variables, such as GDP per capita and public investment in education, which may also influence employability outcomes across countries, should be included in the analysis, as they are important factors in the development of digital skills. Lastly, future research should also aim to address potential endogeneity between digital skills and employment outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Đ. and S.M.Z.; methodology, S.M.Z.; software, S.M.Z.; validation, B.Đ. and M.R.; formal analysis, S.M.Z.; investigation, B.Đ.; resources, B.Đ.; data curation, M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Đ. and S.M.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.R.; visualization, S.M.Z.; supervision, M.R.; project administration, M.R.; funding acquisition, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of the 101120390-USE IPM-HORIZON-WIDERA-2022-TALENTS-03-01 project, funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the European Research Executive Agency can be held responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: [https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database/ (accessed on 30 January 2025)].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Alrifai, A. A., & Raju, V. (2019). The employability skills of higher education graduates: A review of literature. Iarjset, 6(3), 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aum, S., & Shin, Y. (2025). Labor market impact of digital technologies (No. 33469; NBER Working Paper). Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w33469 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Başol, O., & Yalçin, E. C. (2021). How does the digital economy and society index (DESI) affect labor market indicators in EU countries? Human Systems Management, 40(4), 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, E., Alfiero, S., & Leonidou, E. (2022). Remote working and digital transformation during the COVID-19 pandemic: Economic–financial impacts and psychological drivers for employees. Journal of Business Research, 150, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousrih, J., Elhaj, M., & Hassan, F. (2022). The labor market in the digital era: What matters for the gulf cooperation council countries? Frontiers in Sociology, 7, 959091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrus, J., Jackson, T., Xi, N., & Steinberg, J. (2013). Identifying the most important 21St century workforce competencies: An analysis of the occupational information network (O*Net). ETS Research Report Series, 2013(2), i-55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, L., Xia, S., & Coutts, A. P. (2022). Digitalization and employment, a review. ILO. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/employment/Whatwedo/Publications/WCMS_854353/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Chen, P. S. L., Cahoon, S., Pateman, H., Bhaskar, P., Wang, G., & Parsons, J. (2018). Employability skills of maritime business graduates: Industry perspectives. WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs, 17(2), 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M., Adekola, O., Albia, J., & Cai, S. (2022). Employability in higher education: A review of key stakeholders’ perspectives. Higher Education Evaluation and Development, 16(1), 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleff, T. (2019). Applied statistics and multivariate data analysis for business and economics. In Applied statistics and multivariate data analysis for business and economics. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtarelli, M., Gualtieri, V., Jannati, M. S., & Donlevy, V. (2017). ICT for work: Digital skills in the workplace. European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Dangprasert, S. (2023). The development of a learning activity model for promoting digital technology and digital content development skills. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 13(8), 1242–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodel, M., & Mesch, G. (2018). Inequality in digital skills and the adoption of online safety behaviors. Information Communication and Society, 21(5), 712–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2022). Decisions (EU) 2022/2481 of the european parliament and of the council of 14 December 2022 establishing the digital decade policy programme 2030. Official Journal of the European Union, 2022, 4–26. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2023). Digital Decade indicators and trajectories. Available online: https://digital-decade-desi.digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/datasets/dd-trajectories/charts/dd-trajectories?indicator=dd_bds&breakdownGroup=digital_decade&unit=pc_ind&country=EU (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- European Commission. (2024a). DESI 2024 indicators. Available online: https://digital-decade-desi.digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/datasets/desi/charts/desi-indicators?indicator=desi_einv&breakdown=ent_all_xfin&period=desi_2023&unit=pc_ent&country=AT,BE,BG,HR,CY,CZ,DK,EE,EU,FI,FR,DE,EL,HU,IE,IT,LV,LT,LU,MT,NL,PL,PT,RO,SK,SI,ES (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- European Commission. (2024b). DESI 2024 methodological note. European University Institute. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679&from=PT%0Ahttp://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:52012PC0011:pt:NOT (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- European Commission. (2025). Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gazier, B. (2001). Employability—The complexity of a policy notion. In P. Weinert, M. Baukens, P. Bollérot, M. Pineschi-Gapènne, & U. Walwei (Eds.), Employability: From theory to practice (7th ed.). Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Gilster, P. (1997). Digital literacy. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1354072/Digital_Literacy?bulkDownload=thisPaper-topRelated-sameAuthor-citingThis-citedByThis-secondOrderCitations&from=cover_page (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Goldstein, S. (2016, October 10–13). Information literacy: Key to an inclusive society. 4th European Conference, ECIL 2016 (Communications in Computer and Information Science) (Volume 676, pp. 89–98), Prague, Czech Republic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Vazquez, I., Milasi, S., Carretero Gomez, S., Napierala, J., Robledo Bottcher, N., Jonkers, K., & Goenaga, X. (2019). The changing nature of work and skills in the digital age (E. Arregui Pabollet, M. Bacigalupo, F. Biagi, M. Cabrera Giraldez, F. Caena, J. Castano Munoz, C. Centeno Mediavilla, J. Edwards, E. Fernandez Macias, E. Gomez Gutierrez, E. Gomez Herrera, A. Inamorato Dos Santos, P. Kampylis, D. Klenert, M. López Cobo, R. Marschinski, A. Pesole, Y. Punie, S. Tolan, … R. Vuorikari, Eds.). Publications Office. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good Things Foundation. (2019). Improving digital skills for employability. Good Thing Fundation. [Google Scholar]

- Harjono, P. P. (2023). Building digital communication effectiveness in organizations. Journal of Data Science, 1(2), 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, L. (2001). Defining and measuring employability. Quality in Higher Education, 7(2), 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, H. U., & Turiman, S. (2024). Digital content creation course for malaysian english undergraduate students: Its relevance to promote autonomous employability skills. Atlantis Press SARL. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooley, T., & Staunton, T. (2020). The role of digital technology in career development (pp. 297–312). The Oxford Handbook of Career Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU. (2018). Digital skills toolkit. International Telecommunication Union. Available online: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Digital-Inclusion/Documents/ITU%20Digital%20Skills%20Toolkit.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- ITU. (2023). Measuring digital development—Facts and figures 2023. In ITU publications (Vol. 2). International Telecommunication Union Telecommunication, Development Bureau. Available online: https://www.itu.int/hub/publication/d-ind-ict_mdd-2023-1/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Jewell, P., Reading, J., Clarke, M., & Kippist, L. (2020). Information skills for business acumen and employability: A competitive advantage for graduates in Western Sydney. Journal of Education for Business, 95(2), 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska-Spychalska, D. (2018). Digital technologies in the process of virtualization of consumer behaviour—Awareness of new technologies. Management, 22(2), 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, D. M. H., Anwar, A., Gwee, S. L., & Ijaz, M. F. (2023). Impact of acquisition of digital skills on perceived employability of youth: Mediating role of course quality. Information, 14(1), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. N., & Roan, J. (2022). Identifying the development stages of virtual teams—An application of social network analysis. Information Technology and People, 35(7), 2368–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, T. P., & Jacobson, T. E. (2011). Reframing information literacy as a metaliteracy. College and Research Libraries, 72(1), 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuaid, R. W., & Lindsay, C. (2005). The concept of employability. Urban Studies, 42(2), 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauta, A., van Vianen, A., van der Heijden, B., van Dam, K., & Willemsen, M. (2009). Understanding the factors that promote employability orientation: The impact of employability culture, career satisfaction, and role breadth self-efficacy. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(2), 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S., De Reuver, M., & Mahboob Kanafi, M. (2022). Workplace literacy skills—How information and digital literacy affect adoption of digital technology. Journal of Documentation, 78(7), 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, S. (2024). A systemic approach to the determinants of employability. Global Economics Science, 5(2), 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangrazio, L., & Sefton-Green, J. (2020). The social utility of ‘data literacy’. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(2), 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirzada, K., & Khan, F. N. (2013). Measuring relationship between digital skills and employability. European Journal of Business and Management, 5(24), 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Polyakova, V., Streltsova, E., Iudin, I., & Kuzina, L. (2024). Irreversible effects? How the digitalization of daily practices has changed after the COVID-19 pandemic. Technology in Society, 76, 102447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richiardi, M. G., Westhoff, L., Astarita, C., Ernst, E., Fenwick, C., Khabirpour, N., & Pelizzari, L. (2025). The impact of a decade of digital transformation on employment, wages, and inequality in the EU: A “conveyor belt” hypothesis. Socio-Economic Review, mwaf011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, B. (2008). The importance of soft skills: Education beyond academic knowledge. Journal of Language and Communication, 2, 146–155. [Google Scholar]

- Smaldone, F., Ippolito, A., Lagger, J., & Pellicano, M. (2022). Employability skills: Profiling data scientists in the digital labour market. European Management Journal, 40(5), 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinmaz, H., Lee, Y. T., Fanea-Ivanovici, M., & Baber, H. (2022). A systematic review on digital literacy. Smart Learning Environments, 9(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T. L. Q., Herdon, M., Phan, T. D., & Nguyen, T. M. (2023). Digital skill types and economic performance in the EU27 region, 2020–2021. Regional Statistics, 13(3), 536–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutar, Ö. F., & Turhan, F. H. (2023). Digital leisure: Transformation of leisure activities. Shanlax International Journal of Education, 11, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK GOV. (2019). National standards for essential digital skills. Information Policy Team, The National Archives. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-standards-for-essential-digital-skills (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- UNESCO. (2018). Digital skills critical for jobs and social inclusion. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/digital-skills-critical-jobs-and-social-inclusion (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- van Laar, E., van Deursen, A. J. A. M., van Dijk, J. A. G. M., & de Haan, J. (2019). Determinants of 21st-century digital skills: A large-scale survey among working professionals. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Laar, E., van Deursen, A. J. A. M., van Dijk, J. A. G. M., & de Haan, J. (2020). Determinants of 21st-Century skills and 21st-century digital skills for workers: A systematic literature review. SAGE Open, 10(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vărzaru, A. A., & Bocean, C. G. (2024). Digital transformation and innovation: The influence of digital technologies on turnover from innovation activities and types of innovation. Systems, 12(9), 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorikari, R., Kluzer, S., & Punie, Y. (2022). DigComp 2.2. the digital competence framework for citizens. with new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. (2023). Future of jobs report 2023. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2023/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).