Policy or Circumstances? A Synthetic Control Method for Evaluating Brazil’s Economic Boom Under Lula

Abstract

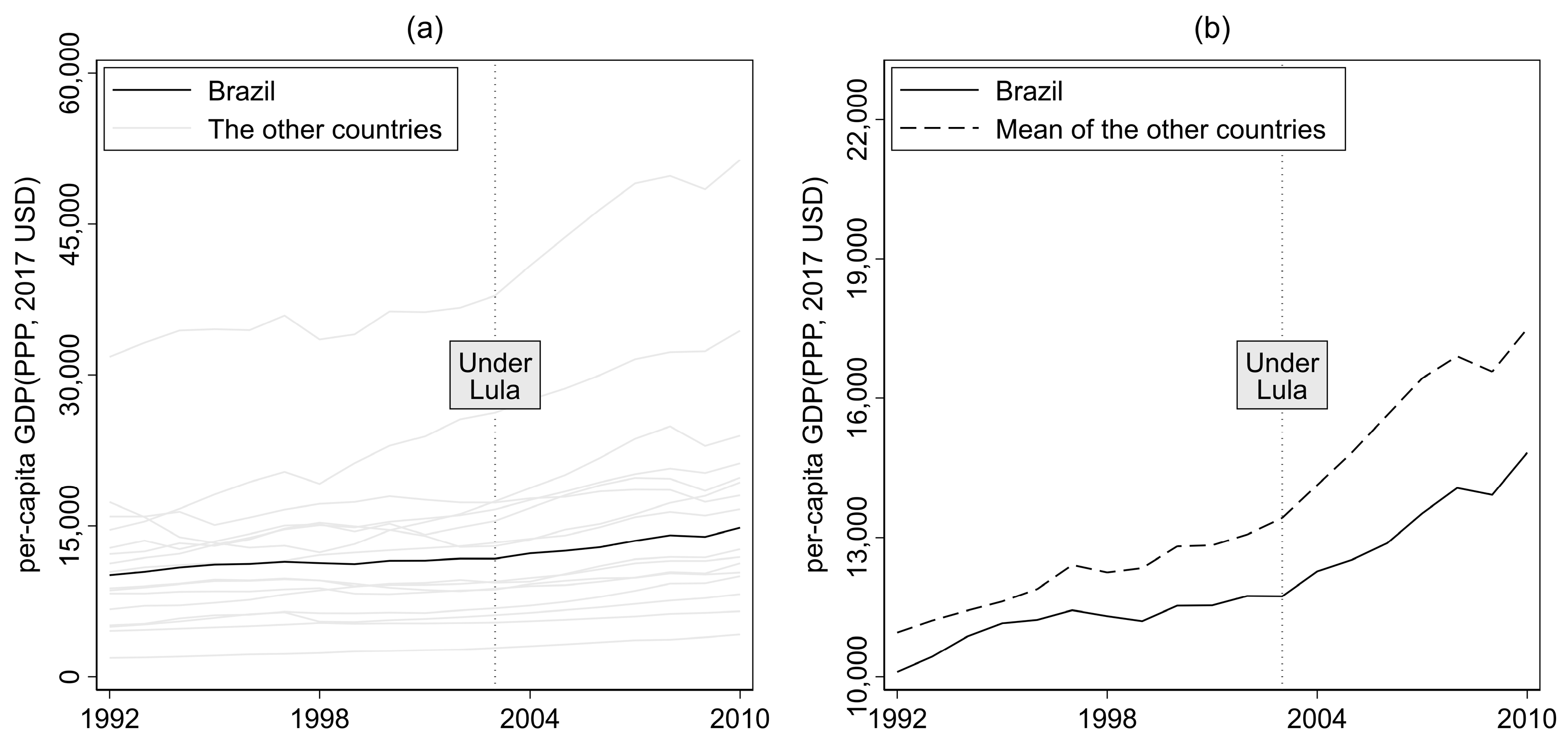

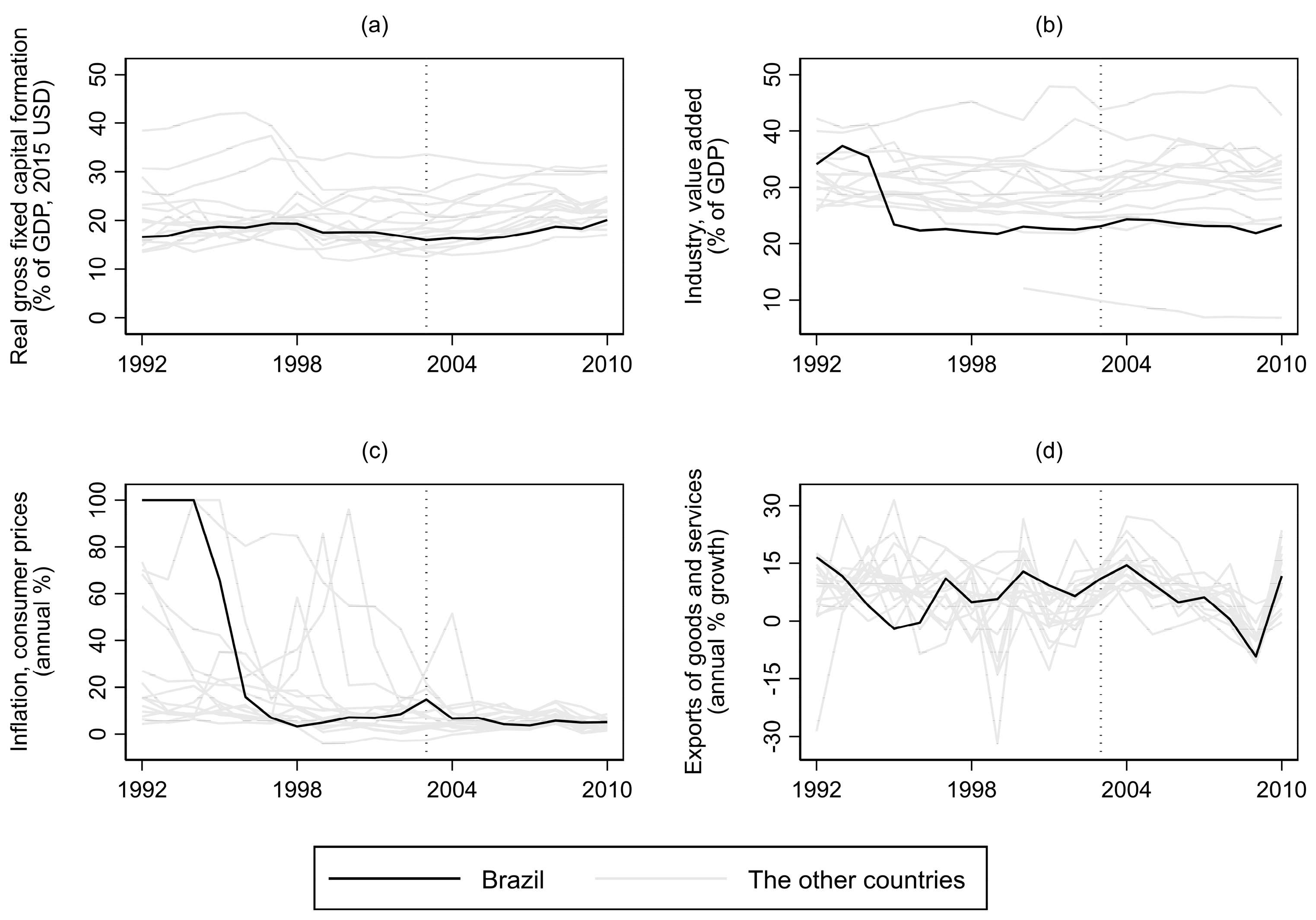

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review: Policy vs. Circumstances

2.1. Policy

2.2. Circumstances

3. Synthetic Control Method

3.1. Baseline Model

3.2. Data

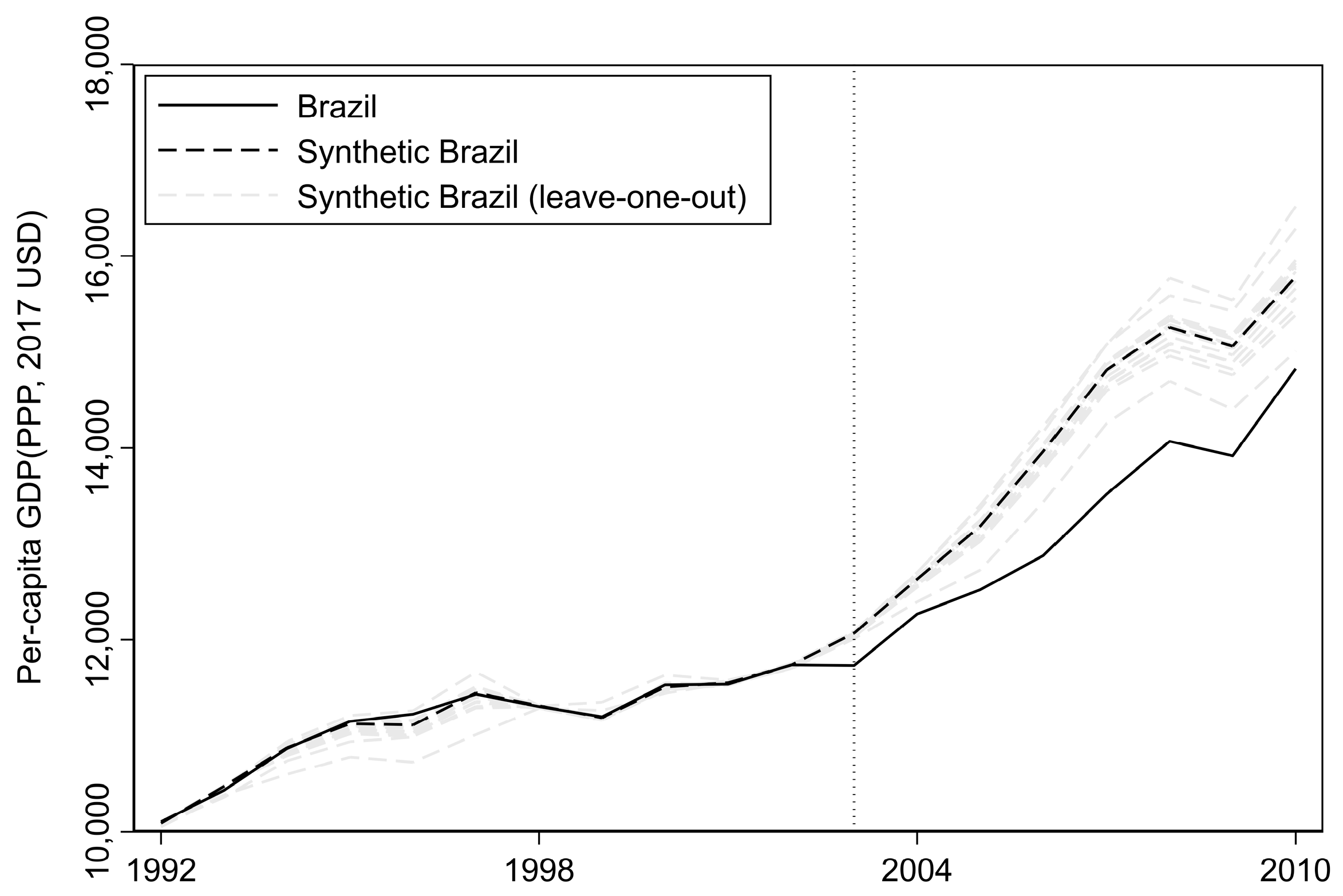

4. Results

4.1. Synthetic Version of Brazil

4.2. Per Capita GDP Trajectory of Brazil and Synthetic Brazil

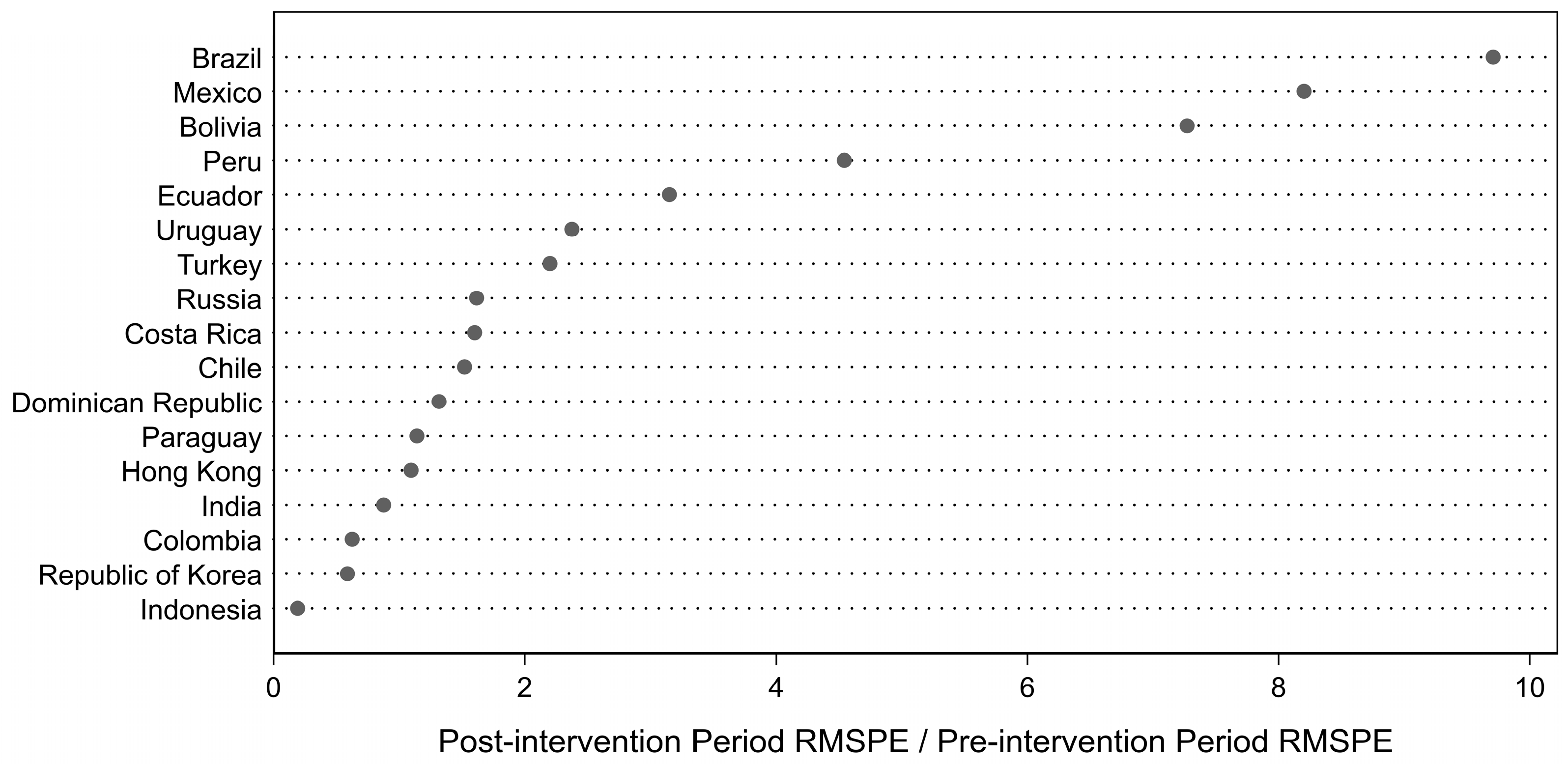

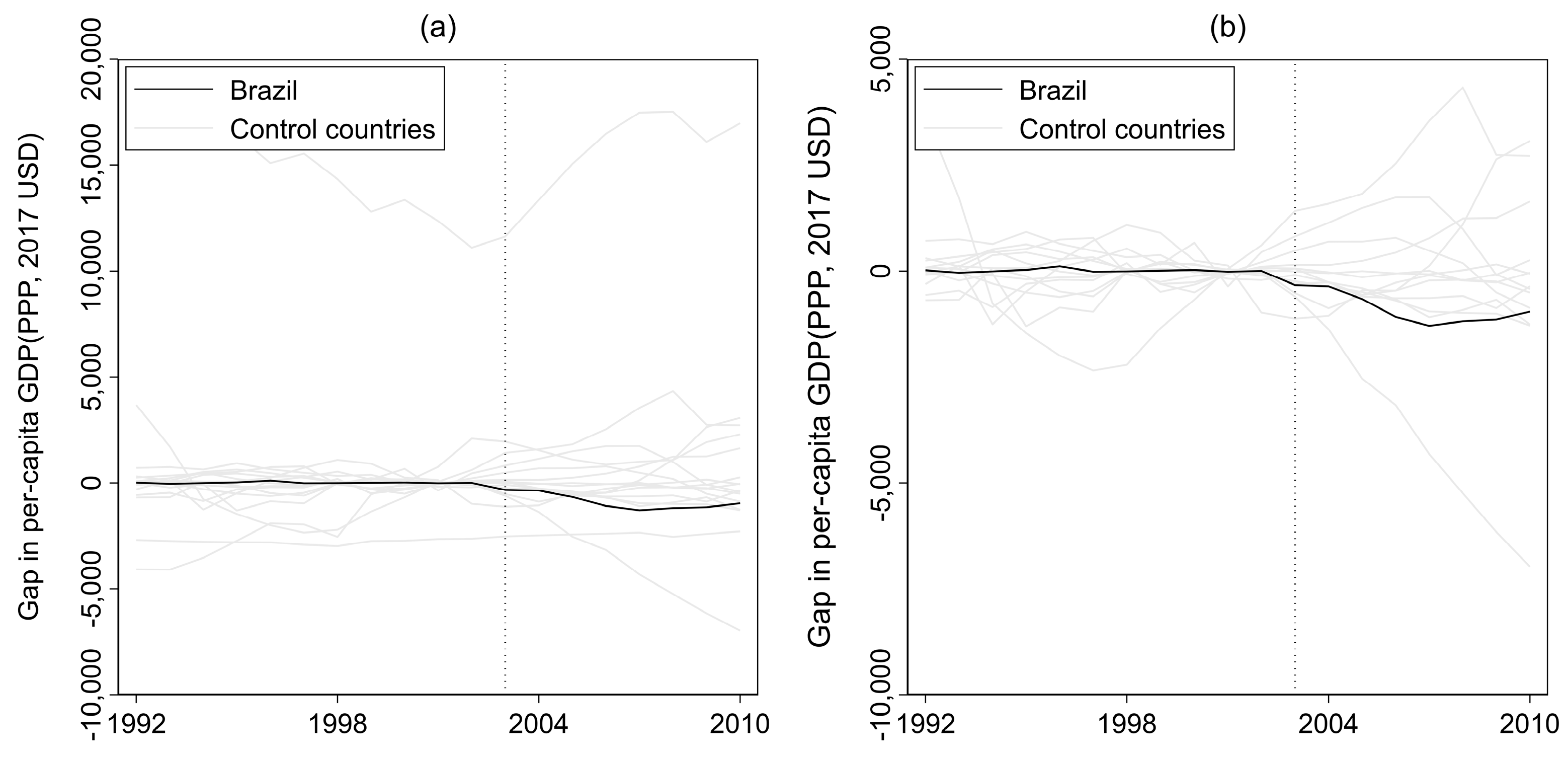

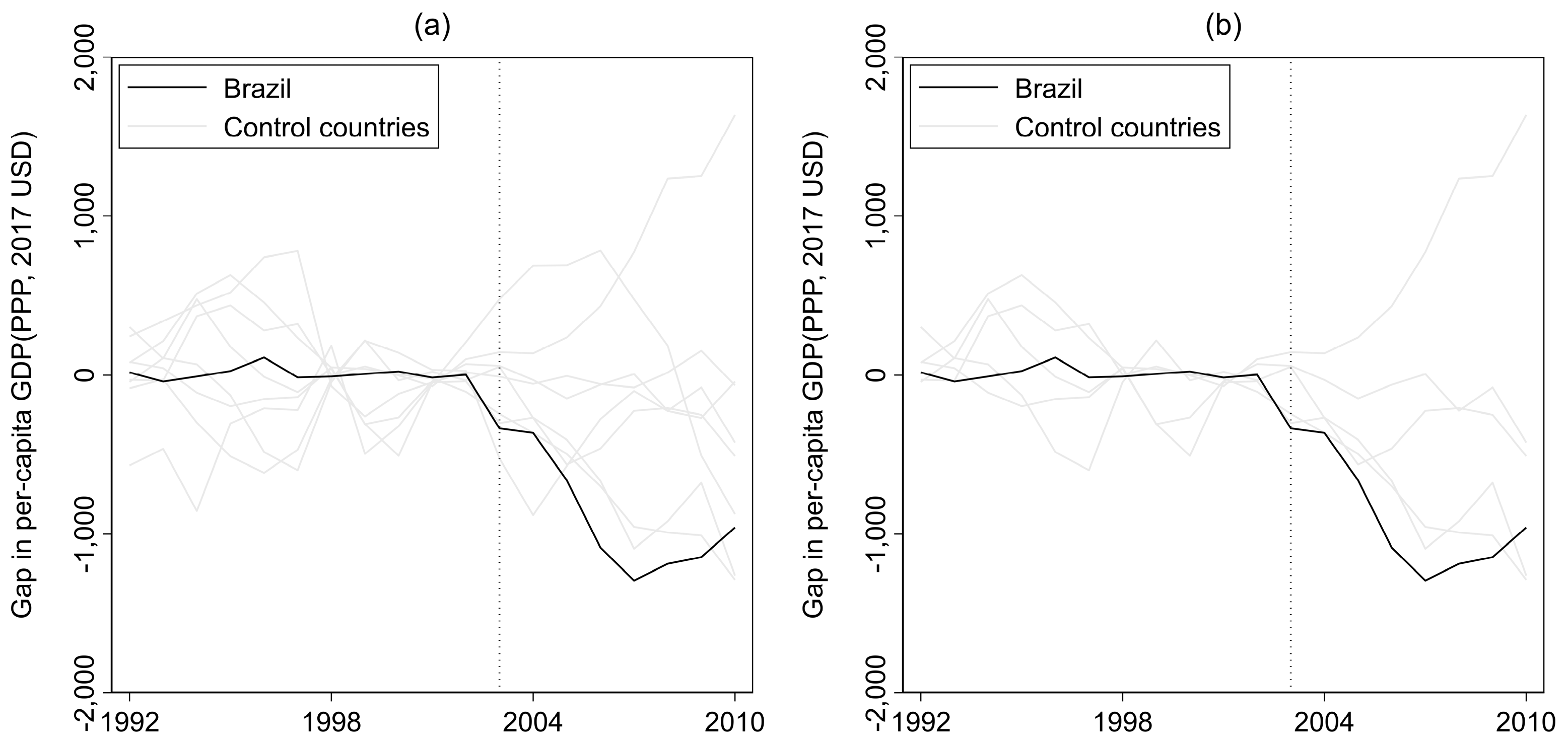

4.3. Robustness Tests

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abadie, A., Diamond, A., & Hainmueller, J. (2010). Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105(490), 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Absher, S., Grier, K., & Grier, R. (2020). The economic consequences of durable left-populist regimes in Latin America. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 177, 787–817. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, C. A. L. (2009). Economia política no Brasil: O primeiro governo Lula [Master’s thesis, PUC-SP]. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P. (2011). Lula’s Brazil. London Review of Books, 33(7), 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, J. M., & Jalles, J. (2014). Brazil: Boosting productivity for shared prosperity. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1135. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgel, F., & Karahasan, B. C. (2016). Thirty years of conflict and economic growth in Turkey: A synthetic control approach. LEQS Paper No. 112. London School of Economics and Political Science, European Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, W., & Silva, A. L. G. d. (2010). Política industrial do governo Lula. Texto para Discussão, IE/UNICAMP, n. 181. Campinas. [Google Scholar]

- Canuto, O. (2023, October). The Brazilian economy’s double disease. Policy Brief No. PB—40/23. Policy Center for the New South. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, V., Mello, J. M. P. d., & Duarte, I. (2014). A década perdida: 2003–2012. Texto para Discussão No. 626. Departamento de Economia, PUC-Rio. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, L., & Rugitsky, F. (2015). Growth and distribution in Brazil in the 21st century: Revisiting the wage-led versus profit-led debate. Working paper. Departamento de Economia, FEA/USP. [Google Scholar]

- Chaise, M. F. (2023). Credit and ideology: The policy of payroll deducted credit during the workers’ party years. Brazilian Political Science Review, 17(1), 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronel, D. A., Campos, A. C., Azevedo, A. F. Z., & Carvalho, F. M. A. (2011). Impactos da política de desenvolvimento produtivo na economia brasileira: Uma análise de equilíbrio geral computável. Pesquisa e Planejamento Econômico (PPE), 41(2), 337–365. [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa, A. (2011, March 20). ‘Futuro chegou’ para o Brasil, diz Obama. BBC Brasil. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/noticias/2011/03/110320_obama_discurso_ac (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Cruz, A. I. G. d., Ambrozio, A. M. H., Puga, F. P., Sousa, F. L., & Nascimento, M. M. (2012). A economia brasileira: Conquistas dos últimos 10 anos e perspectivas para o futuro. BNDES. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas, A. (2019). An eventful two decades of reforms, economic boom, and a historic crisis. In IMF Staff (Ed.), Brazil: Boom, bust, and the road to recovery (Chapter 2). International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, A. M., & Bichara, J. S. (2004). Cambio o continuismo: Una interpretación de la política econômica del gobierno de Lula. América Latina Hoy, 37, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curado, M. (2012). Uma avaliação da economia brasileira no governo Lula. Revista Economia & Tecnologia, 7, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Escher, F., & Wilkinson, J. (2019). A economia política do complexo soja-carne Brasil-China. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural, 57(4), 656–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, M. B. (2009). Retomando o debate: A nova política industrial do governo Lula. Planejamento e Políticas Públicas (PPP), 32, 227–263. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, T. Q. (2018). O boom das commodities dos anos 2000: Uma análise do impacto da alta das commodities nas taxas de investimento direto externo no Brasil. Monografia de Bacharelado, Instituto de Economia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, B., & Gontijo, C. (2024). The limits of Brazilian development between 2003 and 2016. Problemas del Desarrollo, 55(216), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gentil, D. L., & Araújo, V. L. d. (2012). Dívida pública e passivo externo: Onde está a ameaça? Texto para discussão No. 1768. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA), Brasília. [Google Scholar]

- Giambiagi, F., Castro, L., Villela, A., & Hermann, J. (2016). Capítulo 8: Rompendo com a ruptura: O governo Lula (2003–2010). In Economia brasileira contemporânea (3rd ed.). GEN Atlas. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, L. H. M. (2020). Brazil’s economic growth strategy: The last two decades (1999–2019). MPRA Paper No. 118553. Munich Personal RePEc Archive. [Google Scholar]

- Gouvea, R., Li, S., & Vora, G. (2021). The role of China and India in Brazil’s economy. Modern Economy, 12(8), 1263–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A. (2021). The political economy of Brazilian industrial policy (2003–2014): Main vectors, shortcomings and directions to improve effectiveness. Dados, 64(2), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M. (2009). A spatial analysis of Bolsa Familia: Is allocation targeting the needy? In J. L. Love, & W. Baer (Eds.), Brazil under Lula: Economy, politics and society under the worker-president. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Haubert, M., & Spechoto, C. (2022, October 30). Eleito, Lula será cobrado por respostas rápidas na economia. Poder360. Available online: https://www.poder360.com.br/analise/eleito-lula-sera-cobrado-por-respostas-rapidas-na-economia (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Ibrachina. (2024, April 1). China é o maior parceiro comercial do Brasil desde 2009: Relações bilaterais tendem a crescer no futuro próximo. Ibrachina. Available online: https://ibrachina.com.br/china-e-o-maior-parceiro-comercial-do-brasil-desde-2009 (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Kerstenetzky, C. L. (2011). Welfare State e desenvolvimento. Dados, 54(1), 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstenetzky, C. L. (2012). O estado do bem-estar social na idade da razão: A reinvenção do estado social no mundo contemporâneo. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Kerstenetzky, C. L. (2013). Aproximando intenção e gesto: Bolsa Família e o futuro. In T. Campello, & M. C. Neri (Eds.), Programa Bolsa Família: Uma década de inclusão e cidadania (pp. 467–480). IPEA. [Google Scholar]

- Kingstone, P. (2012). The Brazilian miracle and its limits. Law and Business Review of the Americas, 18(4), 455–470. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, M. C., & Nakane, M. I. (2025). Brazilian economy in the 2000’s: A tale of two recessions. Latin American Journal of Central Banking, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A. C. C., & Rodrigues, B. S. (2024). Novo boom das commodities e a crescente participação chinesa na estrutura de comércio exterior do Brasil. Economia e Sociedade, 33(3), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, R. H. D. (2022). What went wrong? The dynamics of the rise and fall of Brazil’s economy (2004–2016) in the perspective of new developmentalism theory. Revista de Estudos Sociais, 24(48), 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, C. A. d. (2015). A influência do salário mínimo sobre a taxa de salários no Brasil na última década. Economia e Sociedade, 24(2), 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M. A. (2008). Unexpected successes, unanticipated failures: Social policy from Cardoso to Lula. In P. Kingstone, & T. Power (Eds.), Democratic Brazil revisited. University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, W. (2022, October 30). Os fatores que explicam a vitória de Lula no 2.º turno da eleição presidencial. Gazeta do Povo. Available online: https://www.gazetadopovo.com.br/eleicoes/2022/lula-os-fatores-que-explicam-a-vitoria-do-petista-no-segundo-turno-da-eleicao-presidencial (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Prates, D. M. (2007). A alta recente dos preços das commodities. Revista de Economia Política, 27(3), 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Quintino, L. (2024, October 2). Brasil a um passo do grau de investimento: Entenda a importância do rating. Veja. Available online: https://veja.abril.com.br/economia/brasil-a-um-passo-do-grau-de-investimento-entenda-a-importancia-do-rating (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Rhee, S.-H. (Ed.). (2011). Modern Brazil: Light and shadow. Seoul National University Latin American Studies Institute, Dosol Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, B. S., & Jabbour, E. (2023). A iniciativa cinturão e Rota e as implicações geoeconômicas para o Brasil. In E. M. Carvalho, D. Veras, & P. Steenhagen (Eds.), A China e a iniciativa cinturão e rota (pp. 93–142). FGV Direito Rio. [Google Scholar]

- Rufín, C., & Manzetti, L. (2022). Institutions and policy choices: The new left in Brazil. Latin American Policy, 13(1), 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santanna, D. (2020). The history of consumer credit in Brazil: From the developmentalist era to Lula. International Journal of Political Economy, 49(3), 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, H. N. L., & Fonseca, R. R. (2022). Crescimento econômico na era Lula (2003–2010): Causas e consequências. Holos, 38(5), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schymura, L. G. (2022). O papel da falta de sorte na década perdida de 2011 a 2020. Conjuntura Econômica, FGV IBRE, 76(2), 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J. A. d. (2016). O crescimento e a desaceleração da economia brasileira (2003–2014) na perspectiva dos regimes de demanda neokaleckianos. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Economia Política, 44, 112–138. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama, N. B. (2008). Theories of diffusion: Social sector reform in Brazil. Comparative Political Studies, 41(2), 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talkington, A. (2011). The postmodern persistence of the Brazilian development state: A comparative study of policies during the Cardoso and Lula administrations. PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal, 5(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valor OnLine. (2011, January 3). Reservas internacionais encerram 2010 em US$288,5 bilhões. Valor OnLine. Available online: https://g1.globo.com/economia/noticia/2011/01/reservas-internacionais-encerram-2010-em-us-2885-bilhoes.html (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Welle, A. C., Grazielle, D., Krepsky, C., Furno, J., Prado, A. D., Araujo, R., & Bastos, P. P. Z. (2022). Dimensões da economia brasileira: Renda, emprego e desigualdade nos governos Lula a Bolsonaro. Nota do CECON N.19. O Instituto de Economia da UNICAMP. [Google Scholar]

- Whitener, B. (2016). From racial democracy to credit democracy: Finance and public security in Brazil. Brasiliana: Journal for Brazilian Studies, 4(2), 221–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wogart, J. P. (2010). Global booms and busts: How is Brazil’s middle class faring? Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, 30(3), 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2008). Global economic prospects 2009: Commodities at the crossroads. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2012). Economic mobility and the rise of the Latin American middle class. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Obs. | Mean. | Std. | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per capita GDP | 323 | 13,497.67 | 8762.21 | 1859.72 | 51,359.81 |

| Investment rate | 323 | 21.15 | 5.67 | 11.69 | 42.13 |

| Schooling | 68 | 19.62 | 8.11 | 5.85 | 39.84 |

| Industry share of value added | 315 | 30.10 | 6.82 | 6.84 | 48.06 |

| Inflation rate | 322 | 32.69 | 173.27 | −4.01 | 2075.89 |

| Export growth rate | 323 | 7.00 | 7.99 | −31.80 | 31.40 |

| Variables | Brazil | Average of 16 Control Countries | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real | Synthetic | ||

| Per capita GDP 1992 | 10,103.8 | 10,086.7 | 10,951.4 |

| Per capita GDP 1998 | 11,304.1 | 11,312.9 | 12,247.6 |

| Per capita GDP 2001 | 11,536.4 | 11,551.8 | 12,831.1 |

| Per capita GDP 2002 | 11,739.4 | 11,736.9 | 13,066.6 |

| Investment rate | 17.9 | 18.2 | 20.9 |

| Schooling 2000 | 14.0 | 18.4 | 18.4 |

| Industry share of value added | 26.1 | 26.3 | 30.7 |

| Inflation rate 1996–2002 | 7.6 | 10.0 | 15.8 |

| Export growth rate | 7.3 | 6.5 | 7.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jung, J.; Kwon, K. Policy or Circumstances? A Synthetic Control Method for Evaluating Brazil’s Economic Boom Under Lula. Economies 2025, 13, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070197

Jung J, Kwon K. Policy or Circumstances? A Synthetic Control Method for Evaluating Brazil’s Economic Boom Under Lula. Economies. 2025; 13(7):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070197

Chicago/Turabian StyleJung, Jaeho, and Kisu Kwon. 2025. "Policy or Circumstances? A Synthetic Control Method for Evaluating Brazil’s Economic Boom Under Lula" Economies 13, no. 7: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070197

APA StyleJung, J., & Kwon, K. (2025). Policy or Circumstances? A Synthetic Control Method for Evaluating Brazil’s Economic Boom Under Lula. Economies, 13(7), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13070197