1. Introduction

Over the past few years, banks around the world have struggled with poor profitability, which poses significant risk to the stability of the financial system, especially for smaller financial institutions. The problem of poor bank profitability is a major worry even if performance measures like return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE) indicated sporadic gains. These numbers fell and never completely recovered during the financial crisis even with several years of low interest rates. Though banks are usually sufficiently prepared to resist financial crisis, improved profitability is required for the build-up of greater buffers of capital and new investments. Persistently poor profitability might motivate banks to take too much risk in order to produce higher profits, thus weakening the system (

Elekdag et al., 2020).

Since the Great Financial Crisis, this link between profitability and systemic risk has been even more highlighted, especially in light of the close ties between monetary policy and bank profitability. Overall system health depends on bank profitability as it reflects banks’ ability to generate a return on their assets and have sufficient capital buffers. Compromised bank profitability can lead to a number of problems including less lending capacity, more risk-taking, and, eventually, system instability. Financial instability not only compounds such problems but can also weaken the efficacy of monetary policy. Monetary policy must react to this as keeping control over general economic circumstances depends on its countering of such volatility. This reaction is especially important as it reflects the relative importance of prominent traits in policy initiatives. Since it affects interest rates and general economic circumstances, monetary policy is one of the most important factors affecting bank profitability. Long-term rates have reached historical lows while short-term interest rates in key industrialized economies have dropped to levels nearly equal to zero or have gone negative. Central banks’ forward guidance and large asset purchases—often known as quantitative easing (QE)—have mostly caused this evolution. Apart from influencing interest rates, QE has been a significant factor in monetary policy. Its function is to influence financial circumstances just like interest rates do. Although there is agreement that a robust central bank reaction is vital in a crisis in its early stages to avoid financial and economic collapse, there has been a growing worry in recent years that the negative consequences of extended monetary accommodation might outweigh the advantages. Low rates are one such negative consequence; they harm bank profitability, which may therefore compromise stability in the financial system (

Borio et al., 2017).

Given this background, it is especially important to investigate not just the direct consequences of unconventional monetary policy measures, such as QE, on bank profitability but also the influence central bank transparency has in forming these results. Especially in periods of financial stress, the interaction between transparent policy communication and asset purchase programs has grown more significant. The current study is based on this additional importance.

This research investigates the combined impact of central bank transparency and quantitative easing on bank profitability, especially during financial stress. Although much research has been done on the separate influence of QE, we contend that transparency, especially via forward guidance, modulates and intensifies the effect of QE. The research therefore tackles two linked research questions: (1) How does QE affect bank profitability in financial crises? and (2) How does the transparency of central banks affect, support, or shape this interaction? Especially during periods of economic stress or financial crises, central bank transparency and quantitative easing (QE) can coexist in ways that are vital for bank profitability. As an unconventional monetary policy instrument, QE has central banks buying significant quantities of assets, usually government bonds, to reduce long-term interest rates and promote economic activity. Central bank transparency refers to clear, consistent, and forward-looking communication about the central bank’s actions, intentions, and goals. These two components taken together can greatly influence bank profitability. All things considered, QE and central bank transparency cooperate to produce a good climate for bank profitability. While central bank transparency, especially in the form of future guidance, helps banks plan their operations with more certainty (

Yellen, 2017;

Woodford, 2012), QE lowers long-term interest rates, raises asset values, and strengthens bank balance sheets (

Bernanke, 2020;

Gagnon et al., 2011). All of these factors help to boost bank profitability with lower funding costs, more lending possibilities (

Borio & Disyatat, 2010), better market stability, and higher consumer confidence. Central banks guarantee that the advantages of QE are completely realized by banks by clarifying and forecasting monetary policy measures, thereby promoting short-term profitability as well as long-term stability.

Building on this dual viewpoint, it is crucial to frame how and why such unconventional actions were carried out. The broader economic context, especially under the limits of the zero lower boundary (ZLB), called for the use of QE as a calculated reaction to severe financial crises. Knowing the reasons and timing of these actions helps one to see more clearly their effects on bank profitability and financial stability.

Particularly when conventional instruments were useless because of the zero lower boundary (ZLB), the application of unconventional monetary policies, such as quantitative easing (QE), has been a vital reaction to severe economic crises. As

Bernanke (

2020) underlines in his study, central banks, including the European Central Bank (ECB), adopted QE not randomly but rather as a deliberate response to systematic disturbances including the 2007–2009 worldwide financial crisis and the following Eurozone debt crisis. The ECB’s measured approach, postponed until 2015 because of legal and political restrictions (

Bernanke, 2020), emphasizes that QE use depended on the degree of crisis and the depletion of conventional policy space.

To foster economic recovery, central banks reacted to the Great Financial Crisis with qualitative and quantitative easing (QE). Although meant to increase economic activity, these policies had a significant effect on bank profitability. This serves as a warning that, with great caution, central banks must balance short-term economic stimulus with long-term financial stability.

During the global financial crisis and its aftermath, the technique of quantitative easing (QE) came out as a major unconventional monetary policy tool. Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Federal Reserve, was instrumental in developing and executing QE programs in the United States, using his academic study on financial crises and liquidity traps (

Bernanke, 2009). Later, his scientific achievements were acknowledged with the 2022 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences given together with Philip H. Dybvig and Douglas Diamond for their work on the function of banks in the economy (

He & Hu, 2023). President of the European Central Bank (ECB), Mario Draghi, enlarged the ECB’s monetary policy toolbox to cover large-scale asset purchases, thereby assisting in stabilizing the Eurozone during its sovereign debt crisis. Although Draghi’s historic 2012 address did not formally declare QE, his statement that the ECB was “ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro” signaled a major policy change. Though motivated by the Fed’s asset purchases, the ECB’s full-scale QE program (2015–2018) was customized to Europe’s particular financial fragmentation issues. This dedication finally opened the road for it.

Given these events, it is imperative to go beyond a limited perspective of QE as just a transient tool to promote lending. Although the direct consequences of QE on market liquidity and interest rates are widely known, more thorough knowledge is required of how such policies interact with bank characteristics, such as central bank transparency, to influence banking sector results. In times of increased financial uncertainty, this viewpoint is especially relevant since the credibility and communication of central banks could either amplify or stabilize the transmission of policies.

Extensive studies in the literature have looked at how bank performance is affected by monetary and fiscal policies. Foundational studies like

Bernanke and Gertler (

1995) and more recent empirical research (e.g.,

Drechsler et al., 2017;

Silva, 2021) have revealed that both conventional and unconventional monetary policy measures, as well as fiscal conditions, greatly influence bank profitability, risk-taking, and provisioning behavior. These connections are now well known. The main contribution of this thesis is not to reiterate these acknowledged impacts but rather to study a less investigated aspect: the influence of central bank transparency on bank profitability, especially in times of quantitative easing (QE). Although current research has mostly concentrated on interest rate channels and balance sheet impacts, this paper seeks to highlight how variations in central bank transparency might change the flow of nontraditional monetary policy to the banking sector. This study also takes into account a wider range of monetary and fiscal indicators to assist this main goal, but always with proper respect for previous studies and their results.

Understanding the specific effects of unconventional monetary policy is essential because central bank transparency significantly shapes the efficiency and predictability of interest rate transmission, especially in emerging economies where clearer policy communication enhances output and price stability without aggressive rate actions, as shown through variance decomposition and impulse response analysis

To fight economic upheaval and the resulting “Great Recession,” many nations have resorted to unconventional monetary policies such as maintaining relatively low interest rates, increasing central banks’ balance sheets by buying a range of hazardous assets including long-term government bonds, corporate bonds, and mortgage-backed securities, and launching initiatives to encourage bank lending (

Lambert & Ueda, 2014). Some central banks—most notably the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank—have also adopted quantitative easing (QE), a major policy outside interest rate changes. To infuse money into the economy and promote financial stability, QE calls for buying long-term securities like Treasury bonds and mortgages.

Hancock and Passmore (

2015), and

Mamatzakis and Bermpei (

2016) claim that the portfolio rebalancing channel, the signaling channel, and the interest rate channel are the most notable transmission channels of QE. These channels, however, are simply a subset of the larger monetary policy framework, which also include other actions including credit facilities and corporate bond purchases—tools vital during the crisis but usually ignored. Originally used in reaction to the 2007–2008 financial crisis, quantitative easing has subsequently played a major role in ensuring financial stability. Importantly, its consequences go beyond just reducing interest rates; it influences more general financial stability and hence bank profitability. Though they also directly influence bank profitability, these avenues of QE are essential for grasping how unusual monetary policy helps to stabilize the economy. Though essential for economic stimulation, low interest rates can harm bank profit margins as conventional lending becomes less profitable. This raises questions about the efficacy of monetary policy, particularly in the presence of financial instability. Financial instability might, in turn, impair the transmission of QE and other monetary instruments, hence compromising the central bank’s capacity to assist the economy and preserve stability. Therefore, it is indispensable to grasp the larger range of QE’s impact—beyond conventional assets and beyond its direct market consequences. While current research emphasizes certain situations or areas—such as the United States or certain European nations—there is a lack of worldwide data on how QE influences bank profitability and financial stability. By looking at how both QE and central bank openness affect bank profitability in different countries, this study hopes to close that gap and emphasize the need of these elements for the general soundness of the financial system.

Monetary policy transmission operates through multiple interconnected channels. The credit channel model created by

Bernanke and Gertler (

1995) offers salient insights on how traditional interest rate impacts are amplified by financial market imperfections. This model emphasizes the external finance premium, the important difference between internal and external financing costs resulting from market friction, including asymmetric information and collateral limits. Two separate but complementary ways show this premium: (1) the balance sheet channel, where monetary tightening lowers asset values and increases debt servicing costs, thereby harming borrower creditworthiness; and (2) the bank lending channel, where contractionary policy lowers bank reserves and so limits credit availability, especially for bank-dependent businesses like SMEs (Small and Medium-sized Enterprises). Even in unconventional policy settings, these channels remain important since quantitative easing activities seek to enhance borrower balance sheets by means of large-scale asset purchases while simultaneously generating possible negative consequences on bank profitability by means of squeezed interest margins. This dual character of transmission mechanisms emphasizes why the credit channel is a significant analytical tool for comprehending the efficacy of monetary policy across both conventional and crisis-period policy regimes.

Drechsler et al. (

2017) suggest the deposits channel as a main driver of bank behavior influenced by monetary policy. They demonstrate that rises in interest rates cause banks, especially in less competitive markets, to raise deposit spreads and lower deposit volumes, hence affecting funding structures and credit supply. Their results highlight the major influence of monetary policy on bank performance.

The health of financial intermediation is absolutely central for monetary policy transmission, as shown by

Bernanke (

1983)’s study of the 1930s catastrophe. Bank collapses and panics disturbed credit flows, hence causing a contraction that struck hardest those most dependent on bank funding: consumers, farmers, and small enterprises. At the same time, deflation raised actual debt loads and diminished collateral values, hence generating a self-reinforcing credit squeeze. These financial accelerator effects extended the decline far beyond what only monetary factors could account for. The crisis exposed how financial frictions change economic shocks: banks limited lending to maintain liquidity, solvent borrowers experienced increased credit costs, and the breakdown of intermediation networks caused ongoing harm. This historical data predicted contemporary credit channel theory by demonstrating why politicians have to consider financial sector weaknesses when judging monetary transmission. The history of the Great Depression is still a strong case study of how disturbances in the credit market can magnify and extend economic downturns.

The historical insights on the Great Financial Crisis emphasize how changes in financial intermediation can magnify recessions and alter the transmission of monetary policy. Building on this basis, more recent empirical research has looked at other, indirect pathways by which monetary policies function in modern economies. The refinancing channel is one such mechanism; it shows how unconventional monetary policies could affect household behavior and aggregate demand.

By recording a refinancing channel, QE-induced drops in mortgage rates prompted household refinancing, which then increased consumption.

Di Maggio et al. (

2020) show more clearly the spread of unconventional monetary policy. This indirect channel supports profit consequences by demonstrating how monetary policy may affect economic activity via family balance sheets.

Extending this worldwide perspective,

Ha et al. (

2020) emphasize how inflation and exchange rate pass-through differ among countries depending on their monetary policy system. Their study shows that, especially in low-inflation situations, credible inflation-targeting policies reduce pass-through impacts and improve monetary transmission channels, hence stressing the structural diversity in policy effectiveness between nations.

Ottonello and Winberry (

2020) build on this by stressing the varied investment reactions of companies to monetary shocks, therefore indicating that financially constrained companies cut investment far more. This investment channel emphasizes how financial frictions change transmission mechanisms and intensify macroeconomic reactions to policy changes by stressing the whole impact of monetary policy (

Ottonello & Winberry, 2020).

By demonstrating that the influence of monetary policy shocks on asset values changes over time, with more effects during times of economic crisis,

Paul (

2020) emphasizes even more the importance of monetary transmission. Asset markets’ time-varying sensitivity emphasizes how monetary actions can affect financial stability and asset values outside conventional interest rate pathways.

Xiao (

2020) shows the transmission of monetary policy via shadow banks by extending this study; he finds that their reactions to interest rate changes vary greatly from conventional banks, particularly in times of financial stress. This difference underlines the need to include non-bank financial intermediaries in evaluating the whole effect of monetary actions.

Building on this,

Gomez et al. (

2021) show that banks’ financial structures greatly influence the transmission of monetary policy via the bank lending channel. Emphasizing how bank-specific traits critically impact monetary transmission and, thus, profitability consequences, their results highlight that larger capitalization and liquidity buffers reduce contractionary effects of policy shocks.

Building on this body of work,

Miranda-Agrippino and Ricco (

2021) demonstrate that shocks to monetary policy—when stripped of central bank information effects—unequivocally lower output, asset prices, credit conditions, and expectations. Emphasizing the transmission of monetary shocks through both conventional and expectational channels, their identification approach supports how flawed information may magnify the actual consequences of policy changes on financial institutions.

De Groot and Haas (

2023) underline the new signaling channel of negative interest rates complementing previous results; under ZLB limitations, policy rate decreases reliably communicate lower-for-longer expectations. Their findings indicate that, even with closing interest margins, the expansionary signaling impact prevails, hence improving the transmission mechanism and the efficacy of monetary policy in low-rate settings.

Koeniger et al. (

2022) support the international relevance of housing markets in monetary transmission by showing that policy rate shocks have a major impact on mortgage rates, tenure decisions, rents, and house prices all throughout Germany, Italy, and Switzerland. Their household-level study shows that institutional and regional financial disparities increase transmission heterogeneity, hence emphasizing housing’s key importance in influencing policy efficacy all across Europe.

Using a model that considers changes in economic conditions, such as high/low interest rates,

Bianchi et al. (

2022) demonstrate that loose monetary policy raises asset prices and reduces risk premiums. Though their emphasis is on more general markets, their results correspond with previous research, (e.g.,

Montecino & Epstein, 2014), on how unconventional policies influence banks

Many studies have looked at how these policies relate to bank profitability in this setting. Examining how the Federal Reserve’s unconventional monetary policies during the financial crisis greatly helped large financial institutions,

Montecino and Epstein (

2014) show that quantitative easing (QE) has a positive and statistically significant impact on banks’ return on average assets (ROAA). While directly assisting to stabilize the financial system, the Fed’s acquisition of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) improved the profitability of the banks who sold these assets. Montecino and Epstein’s study emphasizes that unconventional monetary policies (UMP) especially benefit certain financial institutions by explicitly linking these policies to bank profitability. Conversely, QE has been demonstrated to have a negative and statistically significant impact on net interest margins (NIM), in line with the results of

Mamatzakis and Bermpei (

2016), and verifying prior studies (

Fawley & Neely, 2013;

Krishnamurthy & Vissing-Jorgensen, 2011) that indicate a drop in lending rates as a consequence of unconventional monetary policies, including large-scale asset purchases (LSAP). This narrowing of interest rate spreads shows how these policies directly affect the financial performance of banks, hence weakening bank profitability. Furthermore,

Mamatzakis and Bermpei (

2016) underline that QE could indirectly influence bank asset values. Market players may see the Fed’s purchases as a sign of deteriorating economic conditions,

Christensen and Rudebusch (

2016) say, which would cause trading asset prices to fall and so lower banks’ portfolio profits. These revelations highlight the need to include materials that extensively investigate how unconventional monetary policy affects bank profitability both directly and indirectly instead of just outlining the policies themselves. These policies have a worldwide influence, hence a united perspective between American and European practices is very integral. Examining the link between unconventional policies and bank profitability is very decisive when it comes to grasping the present monetary situation, even if traditional interest rate fluctuations and other conventional policies are still relevant.

The world financial crisis of 2007–2008 underlined the necessity of more efficient supervisory and regulatory tools in the financial industry. Public authorities and central banks’ subsequent actions addressed systematic risk and developing dangers to financial stability beyond basic bank oversight. The change from a micro-prudential to a macro-prudential, all-encompassing perspective of banks emphasizes the need for information sharing and transparency. By means of informed decision-making, central bank transparency helps to improve communication between the central bank and market players. This openness can affect systematic risk, which goes beyond personal risks to include occurrences impacting the whole financial system. The relationship between systemic risk and central bank transparency shows how central bank transparency may affect systemic risk in a diverse banking environment (

Andrieş et al., 2018). Investors, regulators, and other stakeholders can analyze the health and performance of banks by tracking and analyzing central bank data. This is especially important given the lack of research on the effect of transparency on bank profitability even if it has been studied in connection to systemic risk. One of the most important qualities for the efficacy of monetary policy is central bank transparency, which affects inflation levels, inflation variability, GDP levels, and GDP variability. This study aims to find how central bank transparency affects bank profitability. Reflecting a bank’s capacity to control its risks and offer effective financial products and services to its clients, bank profitability is essential for the growth of the financial industry. Knowing how central bank transparency relates to bank profitability can help one to better the performance and stability of the banking system.

Although

Tiberto et al. (

2020)’s study does not directly address bank profitability, their results imply that if transparency lowers credit spreads, it can possibly reduce banks’ interest margins, hence affecting profitability. The total effect on profitability, however, would also be influenced by other elements such the amount of borrowing, the effectiveness of banks, and other income streams.

Deregulation, technological innovation, and the adoption of the euro have contributed to more competition in the European Union banking industry lately. This study emphasizes how market conditions and significant banking traits interact and affect bank profitability. Though there is a wealth of studies on bank performance and structure, little has been written on how new monetary policies—such as quantitative easing and central bank transparency—affect bank profitability. Competition and returns have been affected by structural changes in the banking sector including foreign bank entrance and more transparency in monetary policy. By use of contemporary international data (2013–2019), this research adds to the body of work by examining how these elements influence bank profitability. Unlike other studies, this one particularly looks at how bank profitability is affected by new monetary policies and transparency. These results are crucial for guiding future policies and knowing their more general consequences for financial systems and the economy at large. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. A thorough literature study is given in

Section 2; the data and methods used are described in

Section 3; the empirical findings are covered in

Section 4; and

Section 5 presents the last comments.

2. Literature Review

A key sign of financial health and stability in the banking industry is bank profitability. Policymakers, regulators, and practitioners must grasp how monetary policy influences bank profitability. This literature review is to examine and combine current studies on the link between bank profitability (ROAA ROAE, NIM) and monetary policy. Furthermore, the study investigates a thorough array of independent variables comprising loan-to-asset (LA), overhead-to-asset (OA), equity-to-asset (EA), performing loans (PLs) ratios, bank concentration (competition) (CONC), real GDP growth rate (GDP), annual inflation rate (INF), government debt-to-GDP (DEPT), short-term interbank rate (STR), money supply (M3), quantitative easing (QE) and central bank transparency (TRNS).

Although much of the current research and literature, as well as the majority of other studies, concentrate on profit-oriented commercial banks, it is crucial to recognize that not all banks operate under a for-profit paradigm. Rather than profit maximization, European cooperative banks and American credit unions run on values of mutualism and community focus. Often showing differing risk profiles, these organizations have been shown to be more resilient during economic downturns (

Birchall & Ketilson, 2009). Though this paper does not specifically examine cooperative banks, understanding their unique character is crucial for interpreting results and might pave routes for more comparison studies.

However, despite the extensive research in this area, some issues and differences in the literature still exist, highlighting the need for a comprehensive review to synthesize existing knowledge and identify avenues for future research.

Molyneux and Thornton (

1992) claim the LA/TA ratio reveals a surprising and extraordinary connection between staff expenses and pre-tax return on assets, suggesting a favorable correlation. This result contradicts conventional wisdom and implies that banks running in controlled sectors might be directing their large earnings toward more payroll expenses. Essentially, European banking markets seem to have a cost allocation bias. According to

Sinha and Sharma (

2016), staff expenses have a major and favorable impact on bank profitability. Banks’ investments in acquiring competent and efficient managerial personnel help to explain this good impact, hence helping them to be profitable. Higher profitability is more attainable with good cost management, and the positive effect of such spending indicates a great degree of cost management maturity among Indian banks. Superior management techniques seem to have a good link with profitability. One may conclude that Indian banks have matured to the point where more expenses are linked to more profit production.

Regarding the equity-to-asset ratio (EA),

Barth et al. (

2008) concluded that there is no linear relationship between equity and return.

Performing loans (PLs) play a determinant role in shaping banks’ profitability, with studies emphasizing the impact of performing loans versus non-performing loans.

Altavilla et al. (

2018) report that banks with higher NPL ratios tend to be less profitable.

Directly affecting bank profitability, the four major banks’ market share is evaluated using the CR4 concentration ratio, which also acts as a main tool for examining the market structure and competitive environment (CONC) in the banking sector.

Bourke (

1989) claims that regression analysis employing the CR4 index produces a surprising outcome that challenges conventional wisdom: profitability declines as the CR4 value rises, suggesting a larger market share controlled by the top four banks. This implies that as greater CR4 values are reached, these top banks’ supremacy grows. These banks have to participate in expansionary activities—which require expenses that might not provide instant profits within the same fiscal year—if they are to improve their market position. Launching a new product or entering a new geographic area, for example, involves major costs but produces quite poor short-term profitability. Consequently, a greater market share among the top four banks relates to a drop in return on assets (ROA). Moreover, bigger banks gain from economies of scale that let them reach cheaper marginal costs. Though decreasing prices could harm general bank profitability as well (

Molyneux & Thornton, 1992;

Staikouras & Wood, 2004), this allows these banks to drop their prices to grab more market share.

Studies have underlined how macroeconomic elements, including GDP growth, influence banks’ profitability ratios (

Molyneux & Thornton, 1992;

Staikouras & Wood, 2004). Usually, the relationship with bank profitability is negative since countries with larger GDP are expected to have a banking sector functioning in a mature setting, hence generating more competitive interest rates and profit margins (

Goldberg & Rai, 1996). Since 1994, EU banks have been functioning amid rather rapid GDP growth and falling interest rates. At 5.6%, Ireland had the greatest real GDP growth rate among EU member states in 2019, over four times the EU27 average of 1.5%

Eurostat (

2020). Growth rates are also followed by Greece and Portugal in line with

Staikouras and Wood (

2004).

Inflation (INF), another macroeconomic factor, has always been shown to be a major influence on bank profitability. Examining the impact of rising inflation on return on average assets (ROAA),

Pasiouras and Kosmidou (

2007) discovered it to be noteworthy. On the other hand, domestic and international banks responded with opposite signals. Differences in knowledge of the country’s economic scene and varying inflation rate forecasts between domestic and international banks could explain such contrasting outcomes on macroeconomic conditions. These banks also frequently cater to diverse consumer groups, who could react differently to the same macroeconomic situation.

Though its importance in the banking sector is rising, the effect of government debt (DEPT) on banks’ profitability ratios is still a rather underexplored topic. Research by

Kosmidou et al. (

2015) reveals that banks are extremely exposed to government debt.

Pagoulatos and Quaglia (

2013) and

Provopoulos (

2014) claim that the first debt crisis in Greece touched off a major financial system crisis with notable bank losses and unfavorable asset returns (

Van Dooren, 2017). According to

Cheng and Mevis (

2018), the resulting economic recession struck banks oriented on retail banking especially hard, hence affecting their profitability even after the crisis.

Extensive studies on the link between bank profitability and interest rates have revealed the intricate trade-offs between STR and profitability. The results show that, when considering the endogeneity of policy measures to anticipated macroeconomic and financial conditions, monetary policy easing—such as reducing short-term interest rates or flattening the yield curve—is not always linked with reduced bank profits. In particular, the study by

Altavilla et al. (

2018) shows an uneven impact of the main bank profitability components under accommodating monetary conditions. The negative impact on net interest income is mostly outweighed by the favorable consequences on non-interest income and loan loss provisions. In addition, a lengthy period of low interest rates can have a deleterious effect on wages, but this effect frequently becomes apparent only after a long period and tends to be countered by improved macroeconomic conditions.

The studies of

Molyneux and Thornton (

1992) have addressed how the money supply (M3) influences bank profitability ratios; they identified a negative link between money supply M3 and bank profitability.

Borio et al. (

2017) claim that contractionary monetary policy is likely to lower the money supply, which would raise interest rates and so generate more net interest income; the opposite is also true. The negative relationship seen between profitability and wide M3 money supply suggests that a rise in broad money supply could harm banks’ profitability. Lending rates fall, which significantly impacts bank profitability, thereby explaining this (

Krishna et al., 2021).

Though much study has been done on the factors influencing bank profitability ratios, several areas still need more study, including the influence of quantitative easing (QE) on bank profitability.

Montecino and Epstein (

2014) looked at how bank earnings were affected by the securitized mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market during QE. Their results imply that banks who sold securitized mortgages to the Federal Reserve (Fed) saw both economically and statistically notable rises in profitability. Banks that were significantly “exposed” to MBS purchases also saw higher profits from asset appreciation. Their findings also support this kind of spillover impact and imply that big banks could have been more impacted.

Building on this, additional research has looked at how unconventional monetary policy influences bank conduct more generally. Some have looked at how balance sheet structure affects banks’ reactions to policy interventions including QE instead of concentrating only on profitability. Particularly in the framework of unconventional policy actions like quantitative easing, considerable empirical studies have examined the link between monetary policy and bank performance. Recent studies indicate that monetary policy’s effects vary amongst banks and are mostly determined by their balance sheet makeup and exposure to certain asset classes. For instance,

Rodnyansky and Darmouni (

2017) find that banks with greater ownership of mortgage-backed securities reacted more strongly to quantitative easing initiatives by increasing their lending activities. Their results draw attention to the need for asset-specific transmission channels and stress the diversity of monetary policy impacts across the banking sector. This line of research does not imply the subject is understudied; rather, it shows the intricacy of the transmission process and the need for more research on how such mechanisms influence bank profitability, particularly under various monetary policy regimes.

Bernanke (

2020) backs this viewpoint by contending that, in the post-crisis environment of continuously low nominal interest rates, unconventional monetary tools—especially quantitative easing and forward guidance—have become noteworthy elements of central banks’ toolkits. Not only during crises, but also when markets are operating properly, these methods have been proved to greatly improve financial conditions. QE can encourage credit expansion, asset price increases, and general confidence by reducing long-term interest rates via both portfolio balance and signaling channels. Especially in banks with significant asset purchases, these techniques are probably going to have a direct impact on bank profitability. Bernanke underlines that by about three percentage points, QE can efficiently increase the policy area, hence providing a strong substitute for increasing the inflation goal. Given this, more research is justified on how these new tools—especially QE—influence bank profitability even in non-crisis times.

The work of

Cortes et al. (

2022) offers empirical evidence for

Bernanke (

2020)’s claim that forward guidance and quantitative easing (QE), two unconventional monetary policies, are now important instruments for central banks, especially in a low-interest-rate setting. Their study of the 2008 subprime crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 (Coronavirus Virus Disease 2019) pandemic shows that these regulations not only reduce disaster risk in domestic equities markets but also affect global financial stability. Coordinated efforts by several central banks during the COVID-19 crisis produced favorable spillover effects, hence lowering tail risk perceptions worldwide—a contrast to the one-sided Fed interventions in 2008, which frequently destabilized emerging markets. The study demonstrates how large-scale asset purchases can calm markets and boost confidence, hence complementing Bernanke’s focus on QE’s dual role in crisis response and regular monetary policy. The results, however, clearly show subtle variations: Although QE reduced catastrophe risk for mid-term bonds and stocks, it raised long-term treasury risk during COVID-19, implying trade-offs in policy execution. Given their growing importance in modern central banking, the study emphasizes the need for more research on how these tools—especially QE—affect financial stability and bank profitability outside of crises

Though much research has been done on the elements affecting bank profitability, the literature still has significant gaps and contradictions that call for more research and analysis. Although earlier research has looked at how macroeconomic variables affect bank profitability, more sophisticated studies taking into account the changing character of economic conditions and their changing influence on bank performance—including central bank transparency (TRNS)—are required.

A crucial yet underappreciated element in studies on bank profitability is central bank transparency (TRNS). Transparent monetary policies, as

Papadamou et al. (

2015) demonstrate, improve interest rate transmission and economic stability, which may then affect bank risk-taking and performance, an issue still under research to supplement macroeconomic studies.

When improving policy predictability and lowering market uncertainty, central bank transparency (TRNS) is absolutely essential for macroeconomic and financial stability. Increased transparency in financial stability frameworks links to better financial stability, but non-linearly, as

Horváth and Vaško (

2016) underline, implying an ideal degree past which too much information can compromise stability. This emphasizes the two effects of TRNS on bank risk-taking and economic performance, hence the closing disparities between the efficacy of monetary policy and the resilience of the financial sector.

By limiting policy uncertainty, central bank transparency (TRNS) lowers stock market volatility, hence improving macroeconomic stability and interest rate transmission (

Papadamou et al., 2014). Although this stabilizes financial conditions, its indirect consequences on bank profitability, through risk-taking channels, remain under-researched, hence stressing a need for macro-financial studies connecting TRNS, market stability, and banking performance.

Research like

Cecchetti and Krause (

2002) shows that transparent central banks create credibility and stability by attaining lower inflation volatility and improved policy results. Although transparency stabilizes financial markets, its indirect consequences on bank risk-taking and profitability call for more investigation to completely grasp its macro-financial consequences.

By anchoring expectations and strengthening interest rate dynamics, central bank transparency (TRNS) lowers inflation and output volatility, hence improving the efficacy of monetary policy (

Papadamou et al., 2016). A stable exchange rate also helps macroeconomic stability by reducing uncertainty, which indirectly improves financial performance. This emphasizes the need for TRNS in promoting financial and economic resilience as well.

Greater transparency, as

Crowe and Meade (

2008) demonstrate, helps the private sector to depend more on public information, therefore aligning expectations and reducing inflation volatility. This supports the function of transparency in promoting economic resilience and efficient monetary policy by underlining its advantages for exchange rate stability and financial performance.

With lowering interest rate volatility and anchoring inflation expectations, central bank transparency improves macroeconomic and financial stability, hence strengthening the efficacy of monetary policy. Research indicates that, especially in developing countries, clear rules help to offset the adverse effects of interest rate fluctuations on stock returns, hence promoting financial resilience and economic stability (

Papadamou et al., 2017)

By lowering uncertainty and increasing policy predictability, central bank transparency strengthens macroeconomic and financial stability. Particularly in nations with flexible currency rates and robust institutional frameworks,

Dincer and Eichengreen (

2007) show that more openness is linked to lower inflation and production volatility. Transparency supports the efficacy of monetary policy by promoting responsibility and matching private sector expectations, hence strengthening financial resilience. This is consistent with studies showing that transparent policies reduce negative consequences of interest rate changes, particularly in developing countries, hence promoting economic stability.

Andrieş et al. (

2018), claim that their results show that more central bank transparency helps the banking sector better handle risk. More transparent central banks might be more likely to clearly inform the public and financial markets about their goals and monetary policies. This transparency could serve to lessen uncertainty and support stability in financial markets, which might cause less risk-taking by banks and maybe lower profits on their assets. Moreover, the research by

Mamoon et al. (

2024) finds that independent and transparent central banks significantly reduce non-performing loans (NPLs), implying that these central banks affect the operational performance and financial stability of banks indirectly.

3. Data and Methodology

The data sources, variables, and techniques used to examine the influence of the determinants of bank profitability are shown below. The study is to examine how changes in these determinants affect bank profitability.

3.1. Data

With particular emphasis on the stated independent variables, the review concentrated on empirical research investigating the relationship between monetary policy, macroeconomic conditions, central bank characteristics, bank-specific characteristics, and bank profitability.

Table 1 shows the variable descriptions, definitions, and data sources for the study.

Comprising 3451 observations, our sample is a panel dataset of 493 banks spread across 25 nations from financially advanced areas including the European Union, North America, Central Asia, and the Far East covering the period 2013–2019. To guarantee relevance and consistency, the sample was built using particular criteria. To preserve homogeneity in regulatory and economic situations, we first concentrated on banks from 25 financially mature nations, OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) members. To prevent gaps in the panel dataset, we included only banks with complete financial reporting data for the whole study period (2013–2019).

Though the nation coverage is extensive, the study’s monetary policy and transparency measures relate particularly to four central banks: the European Central Bank (ECB), the Federal Reserve (Fed), the Bank of Japan (BoJ), and the Bank of Korea (BoK). These central banks were chosen because, during the sample period, they were among the few that carried out well-documented, large-scale quantitative easing (QE) programs, as well as consistently recorded transparency practices. It is considered that banks operating under the direct authority of these central banks are immediately impacted by their policies. But, because of the worldwide character of financial intermediation, spillover consequences from these monetary policies are also likely to affect banks in other nations.

Table 2 lists the number of banks by nation and sample characteristics.

This study’s data come from trustworthy sources. Obtained from banks’ balance sheets, financial data include net interest margin (NIM), return on average assets (ROAA), and return on average equity (ROAE). Sourced from commercial databases like BankFocus, these balance sheets guarantee consistent and comparable data.

While central bank balance sheets (QE) are drawn from the central bank of the relevant nation under consideration, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis provides data on monetary policy tools like interest rates (STR) and money supply (M3). This method guarantees the dependability and correctness of the monetary policy data applied in the research.

Data on central bank characteristics, such as central bank transparency, are obtained from the index developed by

Dincer and Eichengreen (

2018).

Relevant indicators, including GDP growth rate, inflation rate, and public debt, are obtained from official statistical sources and international databases to offset macroeconomic elements possibly influencing bank profitability. Specifically, the World Bank provides the GDP growth rate, the OECD the inflation rate, and the IMF the public debt. The concentration index (CONC) is obtained from the World Bank.

The representativeness and generalizability of the results depend on the choice of banks for the survey. The sample consists of commercial banks running in the chosen countries/areas over a defined time frame. Included in the sample’s bank selection criteria are size, market share, and, most critically, the availability of financial data.

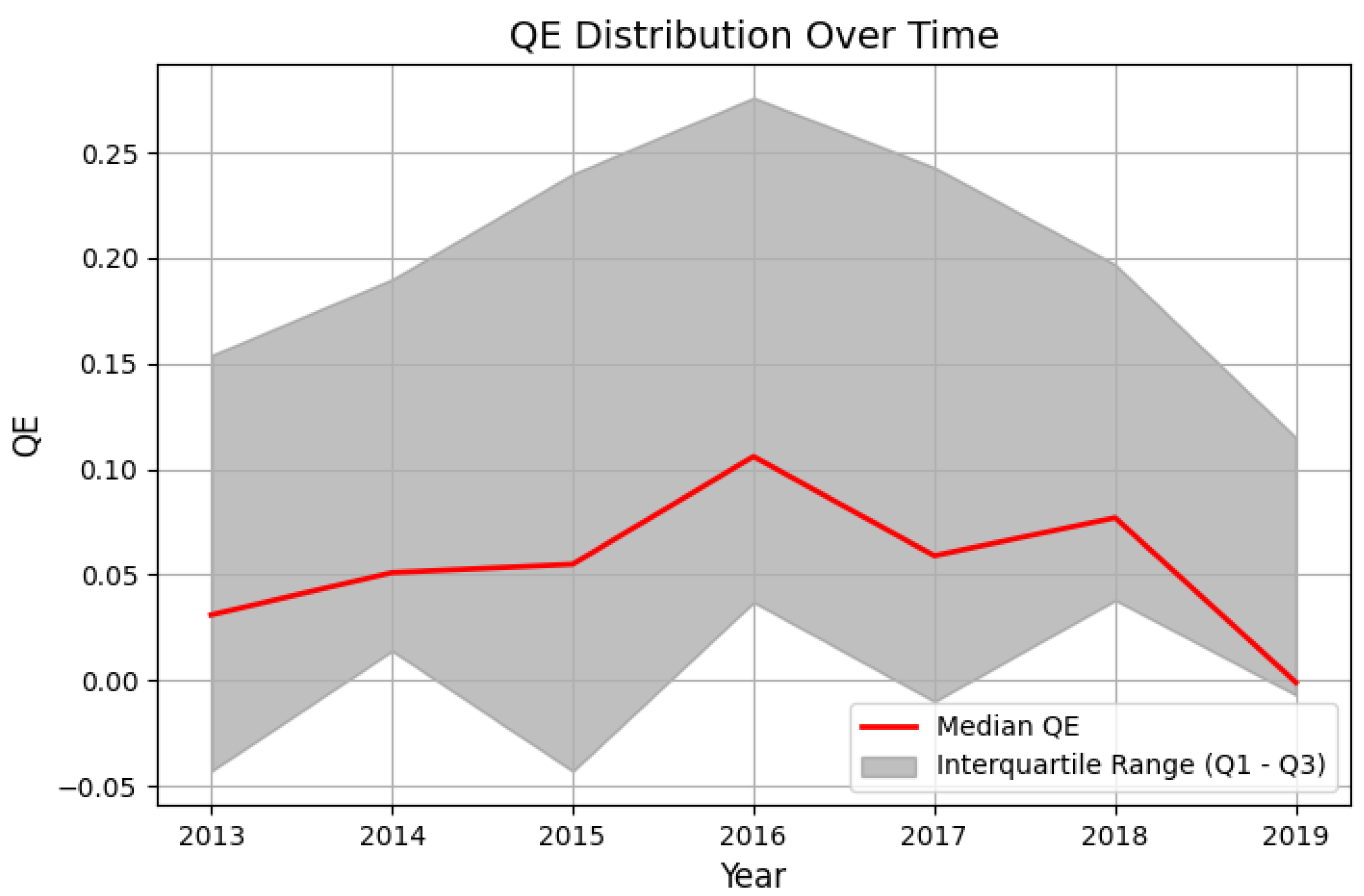

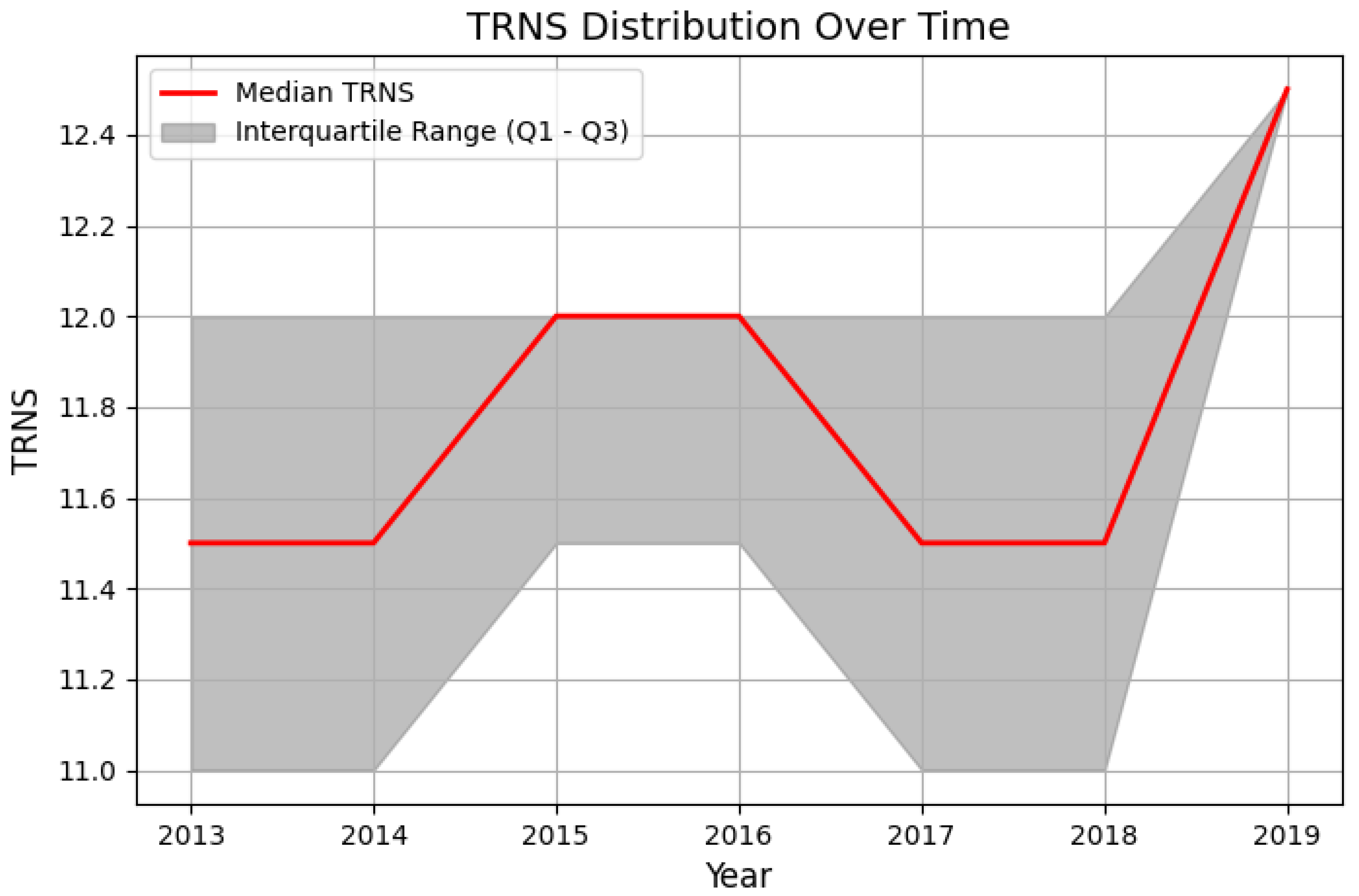

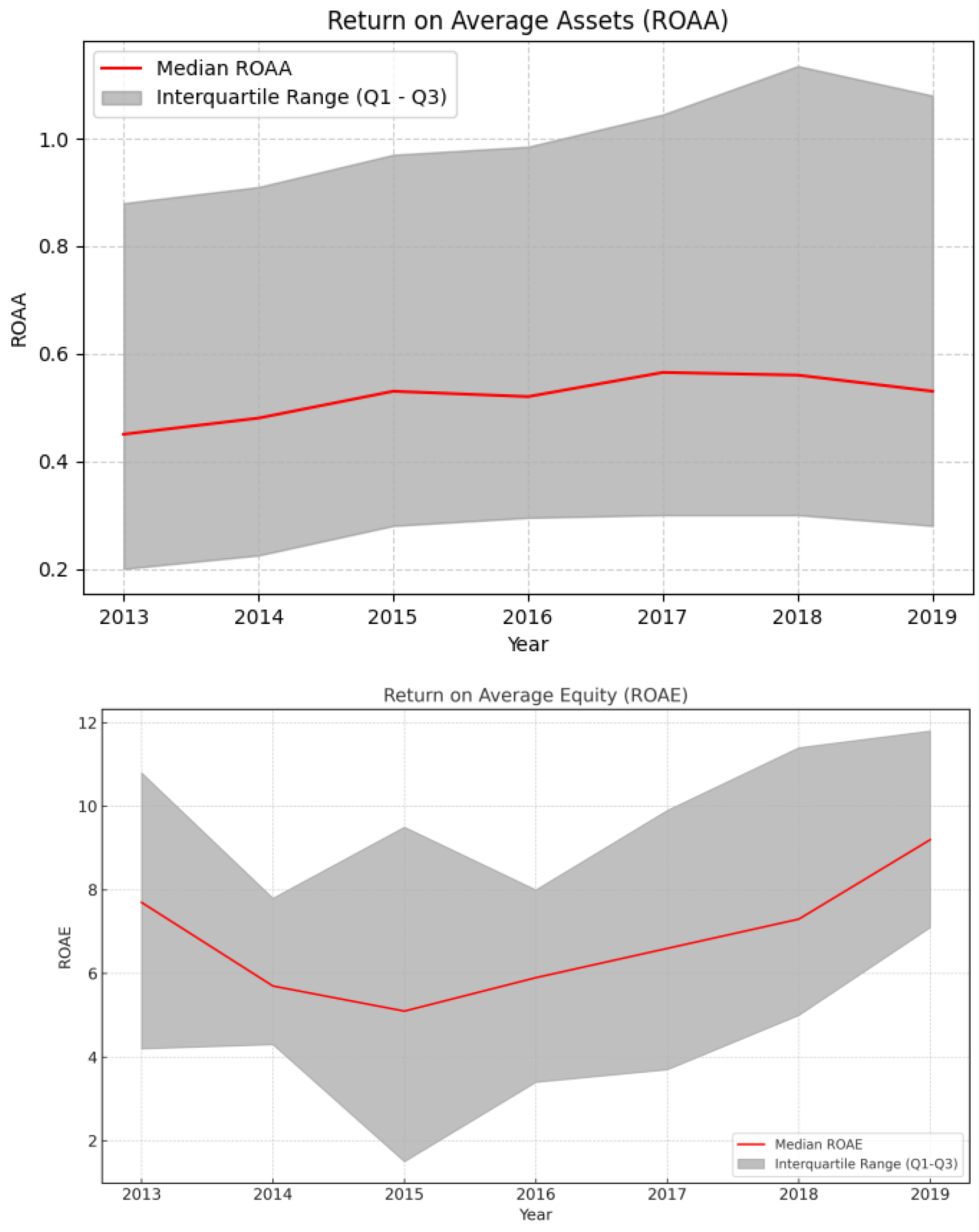

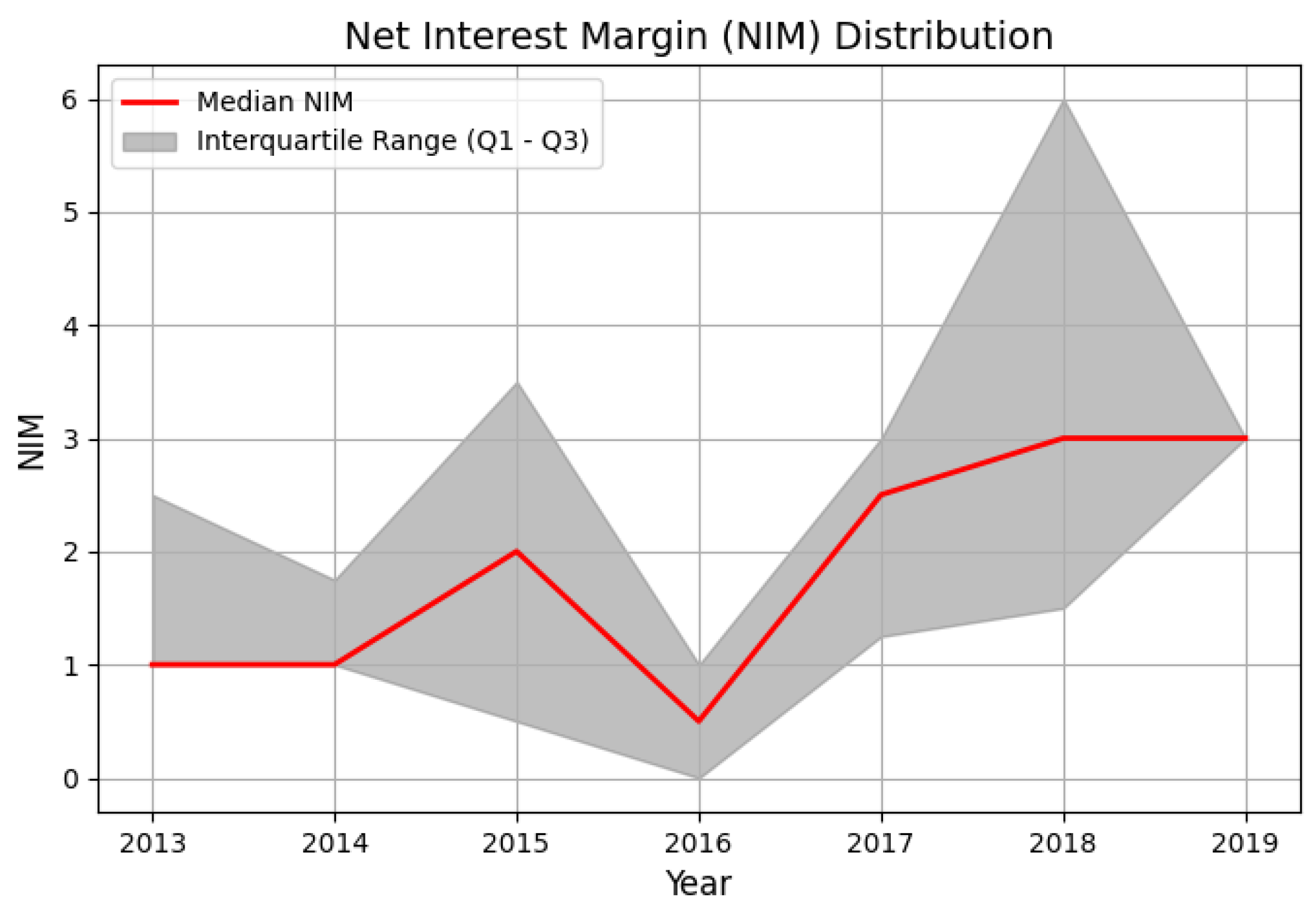

The analysis incorporates descriptive statistics and graphs to offer an overview of the data and highlight key trends and patterns.

It is first required to provide a summary of the descriptive statistics for the variables employed in the study before one explores the empirical investigation. As shown in

Table A1 (

Appendix A), the means and standard deviations of the variables for banks in every country. Among the profitability indicators are net interest margin (NIM), return on average assets (ROAA), and return on average equity (ROAE). The short-term interest rate, money supply growth, and quantitative easing (QE) are among the primary monetary policy variables taken into account.

3.2. Methodology

The effect of monetary policy on bank profitability is examined in the research study using a quantitative method. Panel data analysis and other econometric methods are used in the study to forecast the link between bank profitability and monetary policy measures. By means of the panel data approach, one may control for time and bank-specific effects, hence strengthening the robustness of the results.

The panel regression model was developed to measure how monetary policy affects bank profitability. Furthermore, extra statistical checks, including unit root tests and heteroskedasticity tests, are conducted to guarantee the validity and dependability of the findings.

Endogeneity—when bank profitability might affect the stated balance sheet items and monetary policy choices—is one possible problem. We handle this problem in two ways. First, we lag all bank-specific traits by one period. Second, we apply the dynamic System Generalized Method of Moments (S-GMM) panel approach guaranteeing consistent and unbiased results. This method reduces endogeneity bias and considers the heterogeneity of the data caused by unobservable variables influencing certain banks. Furthermore, our sample’s traits imply that the endogeneity issue might be less important. Though aggregate banking circumstances might influence monetary policy, the performance of a particular bank is less likely to influence the choices of a central bank. Moreover, this danger is reduced even more given that banks operate in several jurisdictions and might not be significant in many of them. For instance, although the status of one nation’s banking system is relevant for macroeconomic circumstances of that nation, it does not affect the economy of another nation in the same manner (

Borio et al., 2017).

Empirical research on monetary transmission raises serious endogeneity issues. Unconventional monetary policies like quantitative easing, which are fundamentally endogenous since they are carried out in direct reaction to macroeconomic conditions, highlight this problem especially. Central banks change their policies reactively, therefore, observed monetary interventions reflect systematic responses instead of exogenous shocks. Following

Bu et al. (

2021), we include annual monetary policy shocks that are both random and free from central bank information influences. This method guarantees that the found shocks show real monetary policy acts instead of endogenous reactions to economic circumstances. Although cross-country applications offer more difficulties because of varied policy transmission mechanisms and data constraints across jurisdictions, this shock-based approach greatly lowers endogeneity. Our shock-based method reduces remaining endogeneity much further. This all-encompassing approach increases the validity of our findings on the influence of monetary policy on bank profitability in many economic settings. Combining lagged variables, dynamic panel methods, and precisely defined monetary policy shocks offers several layers of defense against endogeneity bias while preserving the empirical tractability required for cross-country research. The

Lucas (

1976) Critique highlights how policy changes can systematically alter economic behavior, undermining traditional econometric models. Our method tackles this by: (1) using exogenous central bank monetary policy shocks to find policy-invariant impacts, and (2) contrasting results across institutional contexts, e.g., European vs. U.S. QE, to consider regime-dependent reactions. This combination approach is empirically viable for cross-country research.

With the euro falling by almost 7% after the usual Fed balance sheet increases,

Dedola et al. (

2021) demonstrate that Fed QE announcements cause notable and sustained currency rate fluctuations. Driven mostly by signaling channels and changes in risk premiums, this effect implies that Fed policies not only affect domestic financial conditions but also have far-reaching consequences for overseas banks.

A static panel data model will be used as a further robustness test for the outcomes obtained from the fundamental S-GMM (System Generalized Method of Moments) approach. By means of fixed effects or random effects, this static panel data model allows the verification of the stability and consistency of our results. Validating the robustness of the findings depends on using a static panel model since it provides a counterpoint to the dynamic character of the S-GMM technique.

Furthermore, the static panel model supports the use of techniques like standard error correction and heteroskedasticity testing, which help to confirm the dependability of the estimates. Our goal is to offer a thorough and strong study of the relationship under examination by contrasting the findings from the S-GMM with those from the static panel data model.

3.3. Model

To investigate the factors influencing bank profitability, the following model was created:

Here, i stands for a single bank, t the year, and j the nation where bank i runs. For bank i in year t, the dependent variable Yi,t denotes the return on average assets (ROAA), return on average equity (ROAE) and net interest margin (NIM). X1 is the Bank Characteristics; X2 the Monetary Policy Indicators; X3 the Central Bank Characteristcs; X4 the Macroeconomic Factors; and X5 the Market Structure. The error term is ε.

Expanding Equation (1) to include the variables listed in

Table 1, the model is formulated as follows:

Batten and Vo (

2019) emphasize the need for employing a thorough collection of banking profitability indicators to improve the strength of empirical findings by reflecting many facets of banking activity. Researchers can get a more detailed knowledge of how several elements influence bank performance by using several profitability measures like return on average assets (ROAA), return on average equity (ROAE), and net interest margin (NIM). This multifarious strategy enables the identification and resolution of several aspects of profitability, hence producing more consistent and practical insights.

Bank profitability is evaluated in this paper using net interest margin (NIM), return on average equity (ROAE), and return on average assets (ROAA).

Pasiouras and Kosmidou (

2007) claim ROAA reveals the earnings per euro of assets and suggests how well the bank’s assets are controlled to produce income. Any variations that took place in assets during the financial year are accounted for using average assets. According to

Le (

2017), pre-tax ROAA and ROAE are more complete measures of bank profitability since they reflect operational efficiency and loan loss reserves. Among these two criteria, Le believes ROAA to be more suitable than ROAE for Vietnamese banks, as the equity of these banks is exceptionally low and has experienced notable artificial modifications as a result of government recapitalization initiatives.

A major indicator of a bank’s profitability, the net interest margin (NIM) reveals how well it generates income from loans and investments. Basically, it is the gap between the interest a bank makes on loans and investments and the interest it pays on deposits and borrowed money. Calculating NIM starts with net interest income—the entire interest collected less the total interest paid. To normalize the measure, the resulting value is then divided by the average earning assets over a specified time period. Earning assets include loans and investments producing bank income. Averaging is done by first summing the worth of these assets at the beginning and end of the period and then dividing by two. Expressed as a percentage, NIM measures how well a bank uses its assets to produce profits. While a lower NIM could point to difficulties in generating enough from assets, a greater NIM indicates good profitability. Investors, analysts, and regulators constantly monitor NIM as a sign of financial health and performance as it directly reflects a bank’s capacity to generate income from its main operations.

3.3.1. Bank Determinants

Internal factors of bank efficiency are four banking variables: loan-to-assets (LA), overheads-to-assets (OA), equity-to-assets (EA), and performing loans (PLs). We utilize groups of variables—including monetary conditions, macroeconomic conditions, central bank features and the local bank environment—for the external factors.

The loan-to-assets (LA) ratio is a financial metric utilized in the banking sector to evaluate a financial institution’s risk exposure and its efficacy in using assets for lending activities.

Lin and Zhang (

2009) assert that the ratio (LA) regulates the orientation of the loan portfolio.

Bertay et al. (

2013) utilize it as a customer-centric metric, indicating the degree to which a bank generates loans instead of retaining alternative assets like securities.

The ratio of General Expenses to Total Assets (GO) measures the bank’s overhead or operational expenses, primarily consisting of general wages, and serves to inform about the characteristics of banking expenses within the banking system. This metric is utilized to assess the efficacy of expense management (

Kosmidou, 2008).

This paper uses the equity-to-total-assets ratio (EQAS) as a gauge of capital adequacy. Capital adequacy is the sufficiency of the level of equity to resist any shocks the bank could experience. A bank with a greater ratio of equity to assets will be less reliant on outside financing and hence more profitable. Furthermore, well-capitalized banks are less likely to go bankrupt, which lowers their financing expenses (

Kosmidou, 2008).

Though asset quality is important for all businesses, it is especially crucial for the profitability of banks, which are crucial components of financial markets and the correct operation of banking activities as well as the financial system and hence the national economy. Bank asset quality relates to the quality of loans the bank offers, and the quality of loans can be assessed using non-performing loans (NPLs), which comprises past due loans and monitoring loans (

Altavilla et al., 2018). A major banking indicator measuring the quality and risk connected to a financial institution’s loan portfolio is non-performing loans (NPLs). Serviced loans are those handled by borrowers under specified terms, including consistent principal and interest payments. Basically, these loans are not in default and are seen by the bank as income generating assets.

3.3.2. Market Structure

Yuanita (

2019) claims the concentration ratio (CONC) may also be a sign of competition. Some call it a structural measure of rivalry. Structural data includes market shares, number of companies, entry barriers, and market concentration. Conversely, there is a non-structural assessment that directly assesses competitiveness rather than depending on knowledge of market structure. The Lerner index is one such non-structural method. Structurally speaking, market competition is most often evaluated using the concentration ratio, which indicates the market share held by the largest banks. The structural measure suggests that the concentration ratio affects bank performance.

Using the Loan to Assets (LA) ratio, Overheads to Assets (OA) ratio, Equity to Assets (EA) ratio, the Performing Loans (PLs) ratio, the short-term interest rate (SRT), the money supply (M3), quantitative easing (QE) as a measure of unconventional monetary policy, central bank transparency (TRNS), the real GDP growth rate (GDP), the annual inflation rate (INF), the government debt (DEPT) and the local bank environment (CONC), we investigate how bank profitability relates to bank characteristics, monetary conditions, central bank characteristics, macroeconomic conditions, and market structure.

3.3.3. Macroeconomic Factors

Despite the banking industry’s trend towards increased regional diversification and the increasing use of financial engineering tools to reduce risk, evidence suggests that bank performance is vulnerable to macroeconomic conditions (

Staikouras & Wood, 2004). The three macroeconomic variables used are real GDP growth rate (GDP), annual inflation rate (INF) and government debt (DEPT).

A major macroeconomic indicator reflecting the general economic situation is the growth rate of real GDP (GDP). Now that we are concentrating on the other control factors, we evaluate this important one to reflect macroeconomic stability by including it into our regressions (

Mamatzakis & Bermpei, 2016). Moreover, the national level financial structure is judged by including the GDP growth rate as a gauge of economic activity (

Delis & Kouretas, 2010). Real GDP growth is a consistent sign of the general state and performance of an economy since it reflects the underlying trend in the production of goods and services. Capturing this tendency helps to evaluate stability, offers insightful analysis of economic growth, and enables the methodical tracking of economic performance across time.

The annual inflation rate (INF) is an important economic indicator that reflects the overall price trend in an economy. It is used by governments, businesses and individuals to make decisions about prices, wages and other economic factors.

Public-debt-to-gross-domestic-product (GDP) (DEPT) is a measure of the extent of a country’s public debt in relation to the size of its economy. A nation’s public debt is divided by its GDP to determine it. A country’s fiscal health and sustainability are best indicated by the ratio of public debt to GDP. A high ratio might be worrisome if debt is not controlled, as it suggests that much of the economic output of the nation is utilized to service its debt. Conversely, a low ratio indicates that the nation may be in a better fiscal condition and has quite little debt in relation to its GDP.

3.3.4. Monetary Policy Indicators

The three monetary variables used are the short-term interest rate (STR), the money supply (M3) and quantitative easing (QE)

The way in which changes in the short-term interest rate (STR) influence the return on assets (ROA) of the bank determines the effect of monetary policy on the bank’s profitability. A range of elements that might also affect the planned path of monetary policy and, therefore, the structure of interest rates could cause bank profitability to fluctuate. Changes in ROA might reflect considerations other than those directly related to monetary policy actions (

Altavilla et al., 2018). The overnight interest rate, which relates to the rate at which financial institutions—especially central banks—lend or borrow money from one another on an overnight basis, is what we employ. Monetary policy and the financial stability of a country’s economy are significantly influenced by this interest rate. Central banks utilize the overnight rate as a major instrument to affect the money supply, manage inflation and stabilize the financial system. Central banks utilize this rate to set the price at which banks can access short-term money to cover their reserves or control their liquidity requirements.

The money supply (M3), which is categorized as M1, M2 and M3, is the total quantity of money available in an economy. Often called narrow money, M1 is made up of demand deposits and cash. Often called quasi-money, M2 is M1 plus savings deposits and money market instruments. Referred to as broad money, M3 comprises M3 plus time deposits (

Krishna et al., 2021). Central banks utilize money supply data to evaluate inflationary pressures, economic growth prospects and financial stability, so it significantly influences the formulation of monetary policy. Changes in the money supply M3 also could suggest changes in investor and consumer behavior, hence affecting economic projections and investment choices.

Montecino and Epstein (

2014) claim that when the financial crisis of 2007–2008 broke out, the Federal Reserve lowered short-term interest rates to nearly zero in an effort to assist the financial industry and save the US economy from going into recession. Running out of conventional monetary policy instruments and with nominal interest rates near zero, the Fed resorted to more unorthodox actions. Specifically, it started participating in “quantitative easing,” sometimes known as the Large-Scale Asset Acquisition Program (LSAP), which calls for significant securities purchases (QE). The public argument for these asset purchases was to further encourage economic development by reducing long-term investment returns. Conversely, our study looks at QE at a more granular level utilizing central bank balance sheet size data.

3.3.5. Central Bank Characteristics

Simply said, transparency (TRNS) is the central banks’ revelation of more information. Over the last twenty years, central banks have begun to move toward more transparent policies, hence offering long justifications for their actions and economic projections (

Andrieş et al., 2018). Central bank transparency (TRNS) is the degree to which a country’s central bank freely and efficiently informs the public, financial markets, other pertinent stakeholders of its policies, goals, decision-making processes and financial operations. Such transparency is absolutely necessary to foster financial stability, credibility, responsibility and the efficient operation of monetary policy. As the main entities in charge of a nation’s money supply and interest rates, central banks significantly influence economic conditions. Public confidence, investor confidence, and general economic performance are all directly influenced by central banks’ degrees of openness. Central banks can increase transparency by releasing reports, conducting regular news conferences, offering forward advice on monetary policy, and disclosing details about their balance sheets and operations.

4. Empirical Results

The main results of the research on how monetary policy influences bank profitability are shown in this part. The study draws on a thorough dataset spanning 25 nations over a 7-year period encompassing banks. The paper investigates the link between bank features, monetary policy, central bank traits, macroeconomic conditions, market structure, and several metrics of bank profitability using a strong econometric technique. The following sections summarize and analyze the outcomes.

The ROAE and NIM bank profitability metrics in

Table 3 reveal statistically significant one-year lagged values of the dependent variable influencing present profitability values. The effect of this differs, however, for ROA, ROE, and NIM. GMM estimates showed a non-statistically significant negative lagged profitability coefficient assessed by ROAA, a statistically significant positive lagged profitability coefficient assessed by ROAE, and a statistically significant positive lagged profitability coefficient assessed by NIM at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively, for ROAE and NIM, verifying the dynamic character of the model. (

Elfeituri, 2018;

Uralov, 2020).

Consequently, lagging NIM has a favorable impact on present NIM; lagged ROA values are non-statistically significant, whereas lagged ROE values are statistically significant, and so have a beneficial impact on their present values. This implies that the interest margin in banking systems remains a lucrative source. This fits with the net interest margin being a profit generator for these nations. According to

Bouzgarrou et al. (

2018), lagged ROE’s favorable influence on ROE suggests profit retention for foreign banks. Foreign banks, in particular, are able to keep their profits over time by raising the degree and accessibility of financial services in the domestic financial market.

The next group of findings looks at how central bank transparency (TRNS) relates to bank profitability. The analysis reveals a positive and statistically significant link between higher central bank transparency and measures of bank profitability: ROAA, ROAE, and NIM, at the 5%, 10%, and 10% levels of significance, respectively.

Trabelsi (

2019), who looked at how central bank transparency affected credit markets, found bb using two particular transparency indices—one created by

Dincer and Eichengreen (

2018) for monetary policy transparency and another by

Horváth and Vaško (

2016) on financial stability transparency—whose results imply that if transparency lowers credit spreads, it might lower banks’ interest margins, thereby influencing profitability.

Chen et al. (

2017), who examine how central bank transparency affects several facets of banking including risk-taking behavior, also say that transparency may affect banks’ risk-taking behavior, which could indirectly affect profitability. The analysis indicates that, particularly under expansionary monetary policies, greater transparency in monetary policy could reduce the risk connected with bank operations. This decline in risk could suggest a more stable and maybe profitable financial environment.

The first group of empirical findings emphasizes how bank attributes influence bank profitability. Estimated regression models reveal a statistically significant and positive link at the 1%, 1%, and 5% significance levels (see

Table 3) between the overhead-to-asset (OA) ratio and the three measures of banking profitability: ROAA, ROAE, and NIM. Research efforts between OA and ROAA explore a viewpoint that claims a positive link, implying that higher spending and higher profits might be ascribed to more investment in human capital, hence producing profit (

Molyneux & Thornton, 1992). Other studies investigate a viewpoint indicating a positive correlation between OA and ROAE, as indicated by the work of

Bouzgarrou et al. (

2018), who discovered that domestic banks were marked by the positive effect of structural costs on profitability during the financial crisis. Our results are statistically significant and in line with the above findings suggesting a positive impact on ROAE, probably because banks with greater overhead costs could shift conventional interest-based revenues to commission-based services, which might be less responsive to changes in interest rates and economic crises. During financial crises, this diversification can result in a more stable and greater ROAE. Our results showing a statistically significant and negative relationship between EA and ROAE are consistent with

Tran and Phan (

2020), who found that banks with higher equity might experience a decline in their external debt, thus preventing them from benefiting from financial leverage.

Bouzgarrou et al. (

2018) also claim, thus, that the endogenous character of the capital ratio assessed as equity split by total assets (EA) could account for a negative relationship between EA and ROAE.

Between PLs and bank profitability measures, we have not found a correlation. Similarly, LA is also not statistically significant in relation to bank profitability, as our findings suggest.

Consistent with

Barik and Raje (

2019), where greater operational expenses, which rely on various factors like the effectiveness of the bank’s systems and staff productivity, raise NIM, we anticipate OA to positively influence NIM. This is also in line with our results. The interest margin is mostly explained by operating costs. Operating costs greatly and positively influenced the NIM calculation, according to a

Maudos and de Guevara (

2004) study. Regarding net interest margin (NIM),

Demirgüç-Kunt and Huizinga (

1999) and

Agoraki and Kouretas (

2019) claim EA should have a favorable impact; our results, however, do not corroborate this. By contrast, it is statistically significant and has a favorable impact.

The second group of findings looks at how monetary factors affect bank profitability. Our results confirm past studies showing that interest rates and interest margins are positively related, particularly in a low-interest rate setting (

Argimon et al., 2023). Consistent with

Krishna et al. (

2021), money supply (M3) has a negative and statistically significant impact on ROAA and ROAE since they discovered that rising money supply in a broad sense tends to lower bank profitability by lowering lending rates, therefore greatly lowering bank profits. Modern monetary policy has drawn much interest in terms of the link between quantitative easing (QE) and bank profitability. The research, however, reveals a significant vacuum as no study has looked at all three important profitability indicators—return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), and net interest margin (NIM)—under the impact of quantitative easing at once. By investigating the complex mechanisms at play, our study hopes to close this gap. Emphasizing that quantitative easing affects the key components of bank profitability unevenly might help. Specifically, although it improves the return on average assets (ROAA), this advantage differs from the detrimental effect on net interest margin (NIM). Put otherwise, the increases in profitability from ROAA do not quite offset the NIM losses, implying that, although banks may enhance their general asset returns, they could struggle to keep their interest income during times of quantitative easing. Consistent with the results of

Montecino and Epstein (

2014), quantitative easing (QE) has a positive and statistically significant impact on ROAA. Their research indicates that the Federal Reserve’s unconventional monetary policies during the financial crisis had notable advantages for major financial institutions, particularly the acquisition of mortgage-backed securities (MBS), which boosted the profitability of banks that sold these securities to the Fed. At the same time, these policies aided in stabilizing the financial sector during the crisis. Conversely, quantitative easing (QE) has been shown to have a negative and statistically significant impact on NIM and to be consistent with the results of

Mamatzakis and Bermpei (

2016), as well as being in line with earlier studies indicating that unconventional monetary policy carried out via LSAP has caused lending rates to decline (

Fawley & Neely, 2013;

Krishnamurthy & Vissing-Jorgensen, 2011). So, by reducing interest rate spreads via this route, unconventional monetary policy may affect bank returns. The effect of unconventional monetary policy on bank asset values is yet another mechanism via which bank performance might be harmed. Market players may see the Fed’s acquisitions as a sign that the economic outlook is deteriorating, which would probably affect the worth of trade assets and hence the profits of bank portfolios (

Christensen & Rudebusch, 2016).

The fourth group of findings looks at how bank profitability relates to macroeconomic factors. The study reveals a statistically significant correlation between the measure of bank profitability (ROAA), the annual inflation rate (INF), and the growth rate of real GDP. Previous research (

Yildirim & Philippatos, 2007;

Delis & Kouretas, 2010) has demonstrated a negative association between GDP growth (GDP gr) and bank performance at the country level, according to

Dietsch and Lozano-Vivas (

2000). Additionally, we find that inflation (INFL) has a negative relationship with bank performance, which is consistent with prior empirical evidence (

Wallich, 1977;

Petersen, 1986;

Lozano-Vivas & Pasiouras, 2010) and literature suggesting that bank profits would decline if management is unable to accurately predict the inflation rate and, as a result, adjust interest rates appropriately.

Government debt (DEPT) exhibits a statistically significant and negative relationship with ROAA and ROAE. This result implies that government debt may lower bank profitability. A crisis endangers a nation’s economic future; hence, the expense of impairment is probably rising, which lowers bank profitability. The same is true for the ratio of government debt. Higher impairment expenses mostly explain why increased government debt to GDP lowers net income. A larger public debt ratio lowers the credit rating of government bonds and compels banks to raise loan loss provisions, particularly if they are significantly exposed to government assets (

Cheng & Mevis, 2018).

To ensure the robustness of the findings, numerous robustness tests are performed. These consist of control variables, alternative models, and analyses based on bank characteristics. The results consistently confirm the main findings, reinforcing the validity and reliability of the empirical results.

Robustness tests are an essential methodological issue in the area of econometric research examining how monetary policy influences bank profitability. Robustness tests provide data on the sensitivity of the outcomes, hence evaluating the stability and dependability of empirical results. A basic component in such a study is the decision between static and dynamic models as the principal analytical tool. Often employed in the first analysis, static models offer a quick description of the relationship between variables at a certain moment in time. Their simplicity defines them. By contrast, dynamic models provide a more complete knowledge of the interactions between variables and catch the changing character of economic events throughout time. Robustness tests comparing outcomes from both static and dynamic models are required to guarantee the validity of our results. This approach not only assesses the consistency of the results but also serves to highlight possible problems like endogeneity. A thorough evaluation of the impact of monetary policy on bank profitability should thus comprise robustness tests on various modeling techniques, thereby guaranteeing the robustness and generalizability of our empirical results.