Corporate Concentration and Market Dynamics in Hungary’s Food Manufacturing Industry Between 1993 and 2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Food Systems

2.2. Genealogy of the Hungarian Food Industry

2.3. Historical Background of Corporate Concentration

2.3.1. Factors of Corporate Concentration

2.3.2. Concentration in the European Food Industry

2.3.3. The Consequences of Corporate Concentration

3. Materials and Methods

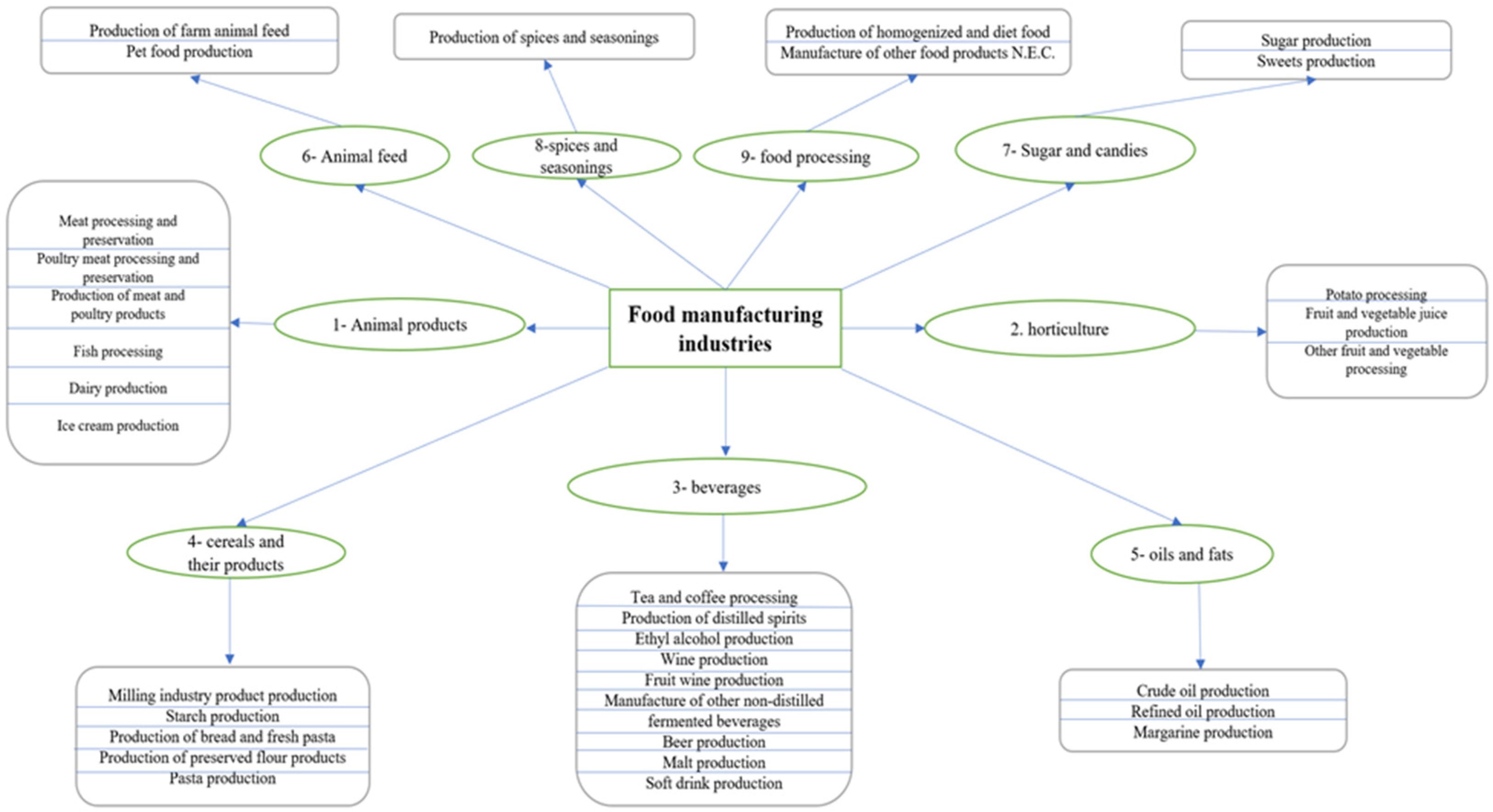

3.1. Data Collection and Categorization

Data Design

3.2. Data Assessment and Statistical Analysis

3.2.1. Assessment of Corporate Concentration

- Unconcentrated Markets: HHI below 1500

- Moderately Concentrated Markets: HHI between 1500 and 2500

- Highly Concentrated Markets: HHI above 2500

3.2.2. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.1. Overall (30 Years) Trend

4.1.2. Short-Term Timeframes

4.2. Annual Trends

4.3. Assessment of Trends over Different Periods

4.4. Assessment of Trends Within Different Sectors

4.5. Assessment of Trends Contributed to Various Priorities

4.6. Assessment of Trends Within the Firm’s Size

5. Discussion

5.1. Corporate Concentration Trends

5.1.1. Periodic Trend of Corporate Concentration

5.1.2. Effects of Corporate Concentration Trends on Operational Factors

5.2. Market Share Structure over Time

5.3. Trends Related to Various Categories

6. Conclusions

7. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aalto-Setälä, V. (2002). The effect of concentration and market power on food prices: Evidence from Finland. Journal of Retailing, 78(3), 207–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, J. (1995). The transition to a market economy in Hungary (6th ed., Vol. 47). Europe-Asia Studies. [Google Scholar]

- András, S. (2014). Foreign direct investments in food industry in Hungary. International Journal of Business and Management Studies, 3(3), 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, H. (2022). Addressing consolidation in agriculture. Center for Agriculture and Food Systems, Issue Brief, 1(9), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Anita, B. (2017). OECD guidelines on corporate governance of state-owned enterprises from Hungarian state-owned enterprises’ point of view. Pro Publico Bono–Public Administration, 5(1), 6–25. [Google Scholar]

- Autor, D., Dorn, D., Katz, L. F., Patterson, C., & Van Reenen, J. (2017). Concentrating on the fall of the labor share. American Economic Review, 107, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor, D., Dorn, D., Katz, L. F., Patterson, C., & Van Reenen, J. (2020). The fall of the labor share and the rise of superstar firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2), 645–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakucs, L. Z., Fertö, I., Hockmann, H., & Perekhozhuk, O. (2018). Market power: An investigation of the Hungarian dairy sector. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/42320686/Perekhozuk_KTI_09-libre.pdf?1454870203=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DMarket_power_An_investigation_of_the_Hun.pdf&Expires=1747213042&Signature=QX7otuM8qDGmIBnUzCPPrfS9TK-U9Ejj8-5DEocMhiyEhOtaRHJ62HpMhFup57OwbGiEjeLRmNLUTq~R2rf-VC6hbliO~ryRBVlzr7HJVUIchl7ak6KNwYqFw84EMgJG9y4luL20E11YZPzrFSUuOjoIO3YXsYs7wusoIERD49oM66dVU0vi0aPTbgmYHs3INA588QDS4cE7m0lfbmhWVCG~4SDTY85qlpmYShAAZ31o7Szm~MZHmdEZxYkorC0z0B4Cv3n4-x2ZX8ijqAthVUvu6~z7j0Bc8Bz~0OcolvaoT4j4OSGHsM7TPBbJfD1E0u6tESNudsDKm9REbINShg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Blažková, I. (2016). Convergence of market concentration: Evidence from czech food processing sectors. Agris On-Line Papers in Economics and Informatics, 8(4), 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blažková, I., & Dvouletý, O. (2017). Drivers of ROE and ROA in the czech food processing industry in the context of market concentration. Agris On-Line Papers in Economics and Informatics, 9(3), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blighe, K., Rana, S., Turkes, E., Ostendorf, B., Grioni, A., & Lewis, M. (2024). EnhancedVolcano: Publication-ready volcano plots with enhanced colouring and labeling. R package version 1.24.0. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/EnhancedVolcano.html (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Bonny, S. (2017). Corporate concentration and technological change in the global seed industry. Sustainability, 9(9), 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M. (1999). Framework issues in the privatisation strategies of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland. Post-Communist Economies, 11(1), 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, J. (2016). Rising corporate concentration, declining trade union power, and the growing income gap: American prosperity in historical perspective. Levys Economics Institute. Available online: https://www.levyinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/e_pamphlet_1.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Brumfield, C., Tesfaselassie, A., Geary, C., & Aneja, S. (2020). Concentrated power, concentrated harm: Market power’s role in creating & amplifying racial & economic inequality. Available online: https://www.georgetownpoverty.org/issues/concentrated-power-concentrated-harm/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Bunce, V., & Csanádi, M. (1993). Uncertainty in the transition: Post-communism in Hungary. East European Politics and Societies, 7(2), 240–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, D., & Lawrence, G. (2013). Financialization in agri-food supply chains: Private equity and the transformation of the retail sector. Agriculture and Human Values, 30(2), 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X., Cao, L., & Gary Krueger, P. (2023). Market concentration and political outcomes market concentration and political outcomes market concentration and political outcomes. Available online: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/economics_honors_projects/115 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Chung, D., & Keles, S. (2010). Sparse partial least squares classification for high dimensional data. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology, 9(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clapp, J. (2018). Mega-mergers on the menu: Corporate concentration and the politics of sustainability in the global food system. Global Environmental Politics, 18(2), 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J. (2021). The problem with growing corporate concentration and power in the global food system. In Nature food (Vol. 2, Issue 6, pp. 404–408). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J. (2022). The rise of big food and agriculture: Corporate influence in the food system. In A research agenda for food systems. Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J. (2023). Concentration and crises: Exploring the deep roots of vulnerability in the global industrial food system. Journal of Peasant Studies, 50(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J. (2024). Countering corporate and financial concentration in the global food system. In Regenerative farming and sustainable diets (pp. 187–193). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J., & Isakson, R. (2018). Speculative harvests: Financialization, food, and agriculture. (Agrarian Change & Peasant Studies). Fernwood. Available online: https://practicalactionpublishing.com/book/2046/speculative-harvests (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Clapp, J., & Purugganan, J. (2020). Contextualizing corporate control in the agrifood and extractive sectors. Globalizations, 17(7), 1265–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J., & Scrinis, G. (2017). Big Food, Nutritionism, and Corporate Power. Globalizations, 14(4), 578–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T. J. (2022). Corporate power and concentration in united states agriculture [Master’s thesis, The University of Utah]. [Google Scholar]

- Csaba, L. (2022). Unorthodoxy in Hungary: An illiberal success story? Post-Communist Economies, 34(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csanádi, M. (2007). Party-state systems and their dynamics as networks. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 378(1), 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cseres, K. J. (2019). Rule of law challenges and the enforcement of EU competition law a case—Study of Hungary and its implications for EU law. Forthcoming in Competition Law Review, 14, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Čechura, L., Žáková Kroupová, Z., & Hockmann, H. (2015). Market power in the European dairy industry. Agris on-line papers in economics and informatics, 7(4), 39–47. Available online: https://online.agris.cz/archive/2015/04/04 (accessed on 6 May 2025). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Daskalova, V. (2020). Regulating unfair trading practices in the EU agri-food supply chain: A case of counterproductive regulation? Yearbook of Antitrust and Regulatory Studies, 13(21), 7–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deconinck, K. (2021). Concentration and market power in the food chain. (OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, Vol. 151). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diprima, G. (2023). The determinants and impact of foreign direct investments. An analysis of Hungary’s FDI inflow [Master’s thesis, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia]. Available online: https://unitesi.unive.it/retrieve/64fe28b8-0247-41b8-b06d-642dd83ddbe9/866993-1273964.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Eddleston, K. A., Otondo, R. F., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2008). Conflict, participative decision-making, and generational ownership dispersion: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Small Business Management, 46(3), 456–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, M., Löf, A., Löf, O., & Müller, D. B. (2024). Cobalt: Corporate concentration 1975–2018. Mineral Economics, 37(2), 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2004). Guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers under the Council Regulation on the control of concentrations between undertakings. Official Journal C, 31, 5–18. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52004XC0205%2802%29 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Expert Market Research. (2024). Top 6 companies in the Europe frozen food market. Expert Market Research. Available online: https://www.expertmarketresearch.com/articles/top-europe-frozen-food-companies (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Fanzo, J., Bellows, A. L., Spiker, M. L., Thorne-Lyman, A. L., & Bloem, M. W. (2021). The importance of food systems and the environment for nutrition. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 113(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehér, I., & Fejős, R. (2006). The main elements of food policy in Hungary. Zemedelska Ekonomika-Praha, 52(10), 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felkai, B. O., & Kuti, B. A. (2022). Situation and development trends of the food industry. Elelmiszervizsgalati Kozlemenyek, 68(4), 4254–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, P. (2006). FDI-led growth and rising polarisations in Hungary: Quantity at the expense of quality. New Political Economy, 11(1), 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Földi, P., Parádi-Dolgos, A., & Bareith, T. (2023). Examination of the performance of food industry enterprises between 2010 and 2021. Regional and Business Studies, 15(2), 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, H., Mcmichael, P., & Friedmann, H. (1989). Agriculture and the state system: The rise and decline of national agricultures* 1870 to the present. Wiley-Blackwell, 29(2), 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, T. (2011). How corporate concentration gives rise to the movement of movements: Monsanto and la via campesina (1990–2011). University of Guelph. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10214/3010 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Golya, G. (2024, February 3). Hungary—Country commercial guide. International Trade Administration. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/hungary-agricultural-sectors (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Gorton, M., & Guba, F. (2000). Foreign direct investment (FDI) and the reconfiguration of dairy supply chains in Hungary. University of Newcastle upon Tyne. Available online: https://www.staff.ncl.ac.uk/matthew.gorton/dualweb.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Greenberg, S. (2017). Corporate power in the agro-food system and the consumer food environment in South Africa. Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(2), 467–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruchy, A. G. (1985). Corporate concentration and the restructuring of the American economy. Journal of Economic Issues, 19(2), 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, A. R., Edwards, D. N., & Sumaila, U. R. (2016). Corporate concentration and processor control: Insights from the salmon and herring fisheries in British Columbia. Marine Policy, 68, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackfort, S., Marquis, S., & Bronson, K. (2024). Harvesting value: Corporate strategies of data assetization in agriculture and their socio-ecological implications. Big Data and Society, 11(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamar, J. (2004). FDI and industrial networks in Hungary. In The emerging industrial structure of the wider Europe (pp. 175–188). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hegyi, J., Troján, S., Kacz, K., & Varga, A. M. (2023). Development of the financial situation of Hungarian food industry enterprises—Changes between 2017 and 2021. Economic and Regional Studies/Studia Ekonomiczne i Regionalne, 16(3), 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, M. K., Howard, P. H., Miller, E. M., & Constance, D. H. (2020). The food system: Concentration and its impacts a special report to the family farm action alliance. Available online: https://www.wfpusa.org/coronavirus/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Herfindahl, O. C. (1963). Concentration in the steel industry (1950). Columbia University. Available online: https://archive.org/details/herfindahl-concentration-in-the-steel-industry-1950-publish/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Hirschman, A. (1945). National power and the structure of foreign trade. California Library Reprint Series. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P. (2021, November 8). How corporations determine what we eat. Welthungerhilfe (WHH). Available online: https://www.welthungerhilfe.org/news/latest-articles/2021/concentration-in-global-food-and-agriculture-industries (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Howard, P. H. (2020). Concentration and power in the food system: Who controls what we eat? (pp. 1–232) Bloomsbury Academic, an Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. Available online: https://www.torrossa.com/it/resources/an/5203342 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Hungarian Ministry of Finance. (2019). The food industry is one of the most promising sectors of the Hungarian economy. Available online: https://2015-2019.kormany.hu/download/4/fb/71000/The%20food%20industry%20is%20one%20of%20the%20most%20promising%20sectors%20of%20the%20Hungarian%20economy.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Hutorov, A., Lupenko, Y., Ksenofontov, M., Bakun, Y., Vlasenko, T., & Sirenko, O. (2022). Strategical development of agri-food corporations in the competitive economic space of Ukraine. Independent Journal of Management & Production, 13(1), 037–055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambor, A., & Gorton, M. (2025). Twenty years of EU accession: Learning lessons from Central and Eastern European agriculture and rural areas. Agricultural and Food Economics, 13(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansik, C. (2000). Foreign direct investment in the Hungarian food sector. Hungarian Statistical Review, SN4(78), 78–104. Available online: http://real.mtak.hu/id/eprint/138506 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Jansik, C. (2004). Food industry FDI-An integrating force between western and eastern European agri-food sectors. Eurochoices, 3(1), 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansik, C. (2002). Determinants and influence of foreign direct investments in the Hungarian food industry in a central and eastern Europan context: An application of the FDI-concentration map method. Agrifood Research. Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:951-687-135-6 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Johnston, P., Frydman, A., Loffredo, J., Péloquin-Skulski, G., Peloquin, G., & Mit, S. (2024). Company towns? Labor market concentration, antitrust opinion and political behavior. MIT Political Science Department Research Paper, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhász, A., Seres, A., & Stauder, M. (2008). Business concentration in the Hungarian food retail market. Studies in Agricultural Economics, 108, 1–13. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/ags/stagec/46443.html (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Juhász, A., & Stauder, M. (2006). Concentration in Hungarian food retailing and supplier-retailer relationships. 16. Available online: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Kaditi, E. A. (2013). Market dynamics in food supply chains: The impact of globalization and consolidation on firms’ market power. Agribusiness, 29(4), 410–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalotay, K. (2006). New Members in the European Union and foreign direct investment. Thunderbird International Business Review, 48(4), 485–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamchedu, A., & Syndicus, I. (2022). Identifying economic and financial drivers of industrial livestock production-the case of the global chicken industry. Tiny Beam Fund, 2022, 40548. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, M. L. (2019). Multisided platforms, big data, and a little antitrust policy. Review of Industrial Organization, 54(4), 695–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, L., Monteath, T., & Wójcik, D. (2023). Hungry for power: Financialization and the concentration of corporate control in the global food system. Geoforum, 147, 103909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadse, A. (2016). Dairy and poultry in India-growing corporate concentration, losing game for small producers. Available online: https://globalforestcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/india-case-study.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Khan, L. M. (2017). Amazon’s antitrust paradox. The Yale Law Journal, 126(3), 567–907. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, E. (2014). Foreign direct investment in Hungary: Industry and its spatial effects. Eastern European Economics, 45(1), 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, J. (1995). Privatization and foreign capital in the Hungarian food industry. Eastern European Economics, 33(4), 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurmai, V. (2016). Market competition and concentration in the world market of concentrated apple juice. Acta Agraria Debreceniensis, 69, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S. Y., Ma, Y., & Zimmermann, K. (2023). 100 Years of Rising Corporate Concentration. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3936799 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Lanier Benkard, C., Yurukoglu, A., & Zhang, A. L. (2021). Concentration in product markets. National Bureau of Economic Research, w28745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- László, V., & Adrienn, B. (2008). Major changes in Hungarian agricultural economy as a result of EU-membership. Gazdalkodas: Scientific Journal on Agricultural Economics, 52(22), 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennert, J., & Farkas, J. Z. (2020). Transformation of agriculture in Hungary in the period 1990–2020. Studia Obszarów Wiejskich, 56, 33–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levins, R. A. (2013). Corporate concentration limits growth in sustainable agriculture. Available online: http://www.leopold.iastate.edu/news/calendar/2009-03-01/2009-shivvers-memorial-lecture-richard-levins-why- (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Lusiani, N., & Divito, E. (2024). Concentrated markets, concentrated wealth. Available online: https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/concentrated-markets-concentrated-wealth/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- MacDonald, J. M. (2020). Tracking the consolidation of U.S. agriculture. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 42(3), 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metabolon. (2025). Partial least-squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). metabolon.com. Available online: https://www.metabolon.com/bioinformatics/pls-da/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Montenegro de Wit, M., Canfield, M., Iles, A., Anderson, M., McKeon, N., Guttal, S., Gemmill-Herren, B., Duncan, J., van der Ploeg, J. D., & Prato, S. (2021). Editorial: Resetting power in global food governance: The UN food systems summit. In Development (Basingstoke) (Vol. 64, Issues 3–4, pp. 153–161). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, P., & Group, E. (2015). CRFA—The changing agribusiness climate: Corporate concentration, agricultural inputs, innovation, and climate change. Canadian Food Studies/La Revue Canadienne Des Études Sur l’alimentation, 2(2), 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordor Intelligence. (2024). Europe plant based food and beverages market size & share analysis—Growth trends & forecasts (2024–2029). Mordor Intelligence. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/europe-plant-based-food-and-beverage-market (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Murphy, S. (2008). Globalization and corporate concentration in the food and agriculture sector. Development, 51(4), 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nes, K., Colen, L., & Ciaian, P. (2021). Market power in food industry in selected EU member states. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiora, K. (2023). Corporate concentration, market structures, and inflationary persistence in Nigeria. Central Bank of Nigeria. [CrossRef]

- Osiichuk, D., & Wnuczak, P. (2023). Do corporate consolidations affect the competitive positioning of non-financial firms in China? Sage Open, 13(4), 21582440231213206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palladino, L. (2019). The American corporation is in Crisis—Let’s rethink it. Boston Review. Available online: https://www.bostonreview.net/forum/lenore-palladino-rip-shareholder-primacy/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Pawlak, K., & Kołodziejczak, M. (2020). The role of agriculture in ensuring food security in developing countries: Considerations in the context of the problem of sustainable food production. Sustainability, 12(13), 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perekhozhuk, O., Hockmann, H., Fertö, I., & Bakucs, L. Z. (2013). Identification of market power in the Hungarian dairy industry: A plant-level analysis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Industrial Organization, 11(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péter, E., & Weisz, M. (2007). Recent trends in the food trade sector of Hungary, the example of the lake Balaton resort area. Journal of Central European Agriculture, 8(3), 381–396. [Google Scholar]

- Pjanić, M., Vuković, B., & Mijić, K. (2018). Analysis of the market concentration of agricultural enterprises in AP Vojvodina. Strategic Management-International Journal of Strategic Management and Decision Support Systems in Strategic Management, 23(4), 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recent Economic Changes in the United States. (1929). Committee on recent economic changes. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Réger, Á., & Horváth, A. M. (2020). Abuse of dominance in the case-law of the Hungarian competition authority—A historical overview. Yearbook of Antitrust and Regulatory Studies, 13(21), 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohart, F., Gautier, B., Singh, A., & Lê Cao, K.-A. (2017). mixOmics: An R package for ‘omics feature selection and multiple data integration. PLoS Computational Biology, 13(11), e1005752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, B. S. (2024). Addressing concentration and consolidation to transform the food system. Drake Journal of Agricultural Law, 29(1), 80–111. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G., Chavas, J., & Stiegert, K. (2010). An analysis of the pricing of traits in the U.S. corn seed market. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 92(5), 1324–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Síki, J., & Tóth-Zsiga, I. (1997). A magyar élelmiszeripar története. MezőGazda Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Snack Food & Wholesale Bakery. (2025). The top candy companies in Europe. snackandbakery.com. Available online: https://www.snackandbakery.com/candy-industry/top-companies-europe#entireList (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Soung-Hun, K. (2008). Market concentration of the processed food in Korea. Journal of Rural Development, 31(5), 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. (2024). Agricultural land area in hungary 2010–2024. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1301421/hungary-agricultural-land-area/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Striffler, S. (2024). Corporate Concentration in the Food Industry. In Oxford research encyclopedia of food studies. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, I., Mroczek, R., Lámfalusi, I., Felkai, B. O., & Vágó, S. (2014). Development of the Polish and Hungarian food industry from 2000 to 2011. Research Institute of Agricultural Economics, 2014, 265–292. [Google Scholar]

- Špička, J. (2016). Market concentration and profitability of the grocery retailers in central Europe. Central European Business Review, 5(3), 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanulmányok, A., I, ván, K., Lukácsik, B., Felkai Beáta, M., Gáborné, O., Valéria, B., Raál, S., Tóth, É., Vágó, P., Közreműködött, S., László, B., Péter, N., & Szerkesztette, T. (2009). Az élelmiszerfeldolgozó kis-és középvállalkozások helyzete, nemzetgazdasági és regionális szerepe (Vol. 9). Agrárgazdasági Tanulmányok. Available online: http://repo.aki.gov.hu/id/eprint/321 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Tesche, J., & Tohamy, S. (1994). Economic liberalization and privatization in Hungary and Egypt. In Working paper series/economic research forum, 9410. Economic Research Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Torshizi, M., & Clapp, J. (2021). Price Effects of Common Ownership in the Seed Sector. Antitrust Bulletin, 66(1), 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, J., & Fertő, I. (2017). Innovation in the Hungarian food economy. Agricultural Economics/Zemědělská Ekonomika, 63, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolomyti, G., Magoutas, A., & Tsoulfas, G. T. (2021). Global corporate concentration in pesticides: Agrochemicals industry. In Springer proceedings in business and economics (pp. 289–297). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. (2010). Horizontal merger guidelines. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2010/08/19/hmg-2010.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- van Dijk, M., Morley, T., Rau, M. L., & Saghai, Y. (2021). A meta-analysis of projected global food demand and population at risk of hunger for the period 2010–2050. Nature Food, 2(7), 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zuilekom, F., & Morrison, A. (2013). Analysing foreign direct investment externalities in the central eastern european region: Evidence from the Hungarian food industry. Utrecht University. Available online: https://studenttheses.uu.nl/handle/20.500.12932/12996 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Vorley, B. (2003). Corporate concentration from farm to consumer. Available online: www.iied.org (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Wall, T. (2023, July 5). 10 top European pet food companies in 2022. Available online: https://www.petfoodindustry.com/news-newsletters/pet-food-news/article/15541758/10-top-european-pet-food-companies-in-2022 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Williams, M. J. (2022). Care-full food justice. Geoforum, 137, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Food Programme. (2024). Food systems. World Food Programme (WFP). Available online: https://www.wfp.org/food-systems (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Wynne-Jones, S. (2024). Top 20 most popular food brands in Europe. European Supermarket Magazine. Available online: https://www.esmmagazine.com/a-brands/top-20-most-popular-food-brands-in-europe-251584 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Yu, W., Chavez, R., Jacobs, M. A., & Feng, M. (2018). Data-driven supply chain capabilities and performance: A resource-based view. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 114, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. (2024). Corporate concentration of power in the global food system: Dynamics, strategies and implications (pp. 815–822). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Sub-Category | Active Companies | Number of Workers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decades | 1993–2002 | 4825 | 429,575 |

| 2003–2012 | 5249 | 326,430 | |

| 2013–2022 | 6414 | 338,781 | |

| Sector | Animal feed | 1531 | 65,016 |

| Animal Products | 3502 | 412,580 | |

| Beverages | 2545 | 177,964 | |

| Cereals and their products | 4247 | 149,477 | |

| Food processing | 904 | 50,416 | |

| Horticulture | 2224 | 79,585 | |

| Oils and fats | 407 | 42,365 | |

| Spices and seasonings | 349 | 24,406 | |

| Sugar and candies | 779 | 92,977 | |

| CR4 of company size and | 0–4 persons | 61 | 8 |

| Company No | 5–10 persons | 101 | 265 |

| 11–20 persons | 201 | 1089 | |

| 21–50 persons | 811 | 4178 | |

| 51–300 persons | 756 | 154,745 | |

| 301–1000 persons | 214 | 96,140 | |

| >1000 persons | 7 | 278,998 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Imani Bashokoh, M.; Tóth, G.; Ali, O. Corporate Concentration and Market Dynamics in Hungary’s Food Manufacturing Industry Between 1993 and 2022. Economies 2025, 13, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050136

Imani Bashokoh M, Tóth G, Ali O. Corporate Concentration and Market Dynamics in Hungary’s Food Manufacturing Industry Between 1993 and 2022. Economies. 2025; 13(5):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050136

Chicago/Turabian StyleImani Bashokoh, Mahdi, Gergely Tóth, and Omeralfaroug Ali. 2025. "Corporate Concentration and Market Dynamics in Hungary’s Food Manufacturing Industry Between 1993 and 2022" Economies 13, no. 5: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050136

APA StyleImani Bashokoh, M., Tóth, G., & Ali, O. (2025). Corporate Concentration and Market Dynamics in Hungary’s Food Manufacturing Industry Between 1993 and 2022. Economies, 13(5), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050136