1. Introduction

The Abuja Declaration of 2001 represents a significant commitment by African governments to prioritize healthcare funding, aiming to enhance health outcomes and alleviate poverty across the continent in alignment with United Nations objectives. In sub-Saharan Africa, high out-of-pocket (OOP)

1 household health expenditures are a major contributor to persistent poverty, hindering progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 1 (No Poverty) and Sustainable Development Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being). Many families face substantial healthcare costs that consume a significant portion of their income, forcing them to forgo essential medical services and exacerbating health disparities (

World Bank, 2021a). Despite the Abuja Declaration’s requirement for member states to allocate at least 15% of their annual budgets to healthcare, public health spending in the region remains insufficient and poorly managed, failing to provide essential financial protection and accessible healthcare services to the population (

African Development Bank, 2023). However, adherence to this commitment has been limited. As of 2021, only two countries—South Africa and Cabo Verde—met this target. In 2020, domestic general government spending on health as a percentage of total government expenditure varied significantly across sub-Saharan Africa, ranging from 2.1% to 12% (

WHO, 2020). These figures indicate that, on average, sub-Saharan African countries allocate less than half of the 15% target to health, highlighting a substantial deviation from the Abuja Declaration’s objectives. The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted these deficiencies, emphasizing the urgent need for increased and more effective public health investments to mitigate the impact of out-of-pocket expenses on impoverished households and accelerate progress towards SDG1 and SDG3 (

IMF, 2022). Comprehensive policy reforms are urgently needed to strengthen public health expenditure, improve healthcare infrastructure, and implement robust financial protection mechanisms to prevent healthcare costs from further impoverishing vulnerable populations (

UNESCO, 2024;

UNDP, 2020).

In comparison to other regions, government health expenditure in Africa, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, is relatively low. The region’s average health expenditure as a percentage of GDP is around 5.6%, which is significantly lower than that of high-income countries. For instance, many African countries spend less than USD 44 per capita on health, which is below the minimal level defined by international standards. This is partly due to higher out-of-pocket expenditures and limited budget allocations to the health sector (

World Bank, 2024). As for Average GHE by Region, GHE varies significantly across different regions: The average health expenditure for OECD is approximately 9.2% of GDP, with some countries reaching up to 10% or more. Health expenditure for East Asia and the Pacific averages around 5.2% of GDP. Health expenditures for Latin America and the Caribbean ranges between 6% and 8% of GDP. These figures highlight substantial disparities in health spending, with developed regions typically allocating a higher percentage of their GDP to health compared to developing regions (

World Bank, 2024).

Before the Abuja Declaration of 2001, many African countries, including Nigeria, had limited healthcare policies that struggled with inadequate funding, poor infrastructure, and unequal access to services. The focus was on Primary Health Care (PHC), inspired by the Alma-Ata Declaration, but it was often underfunded and lacked proper implementation. Governments spent little on healthcare, often relying on donor aid and international organizations, which led to fragmented programs. Health systems were weak, with significant disparities between urban and rural areas. The Abuja Declaration aimed to address these issues by urging African governments to allocate at least 15% of their national budgets to healthcare, signaling a shift toward more substantial and sustained domestic investment in health (

WHO, 2001).

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) shows significant variations across its sub-regions, each facing distinct health and economic challenges. East Africa, with countries like Kenya and Ethiopia, has seen rapid economic growth and improvements in healthcare access, but struggles with high poverty rates, underfunded health systems, and over 50% of health expenditure coming from out-of-pocket payments (

WHO, 2020). Southern Africa, including South Africa and Botswana, has a more developed healthcare system but faces inequality and high HIV/AIDS rates, with disparities in healthcare access exacerbating poverty (

Geyer, 2019). West Africa, which includes countries like Nigeria and Ghana, faces challenges such as low per capita health spending, high infant mortality, and health-related costs that exacerbate poverty. According to the

World Bank (

2018), nearly 30% of the population in West Africa is pushed into poverty each year due to healthcare expenses. Central Africa, including Cameroon and the DRC, grapples with instability, poor infrastructure, and limited health funding, leading to high rates of preventable diseases and maternal mortality. In contrast, North and West African countries, while having better health financing, still struggle with political and economic instability, affecting health outcomes. These regional disparities highlight the need for tailored approaches to improving health systems and reducing poverty in SSA.

Despite these efforts, sub-Saharan Africa continues to face significant challenges in healthcare accessibility and affordability, with out-of-pocket household health expenditure often imposing a substantial financial burden on households, particularly those living in poverty (

Wagstaff & Doorslaer, 2003). The region continues to have the highest rates of poverty, with approximately 40% of its population living below the international poverty line of USD 1.90 per day (

World Bank, 2021b). Understanding the dual impact of out-of-pocket expenditures and public health spending on poverty is essential for evaluating the effectiveness of health financing policies in achieving sustainable development goals. While public health expenditure aims to enhance healthcare access and reduce financial barriers, excessive out-of-pocket costs can exacerbate poverty by pushing households further into economic hardship and widening socioeconomic inequalities (

Van Doorslaer et al., 2007). Moreover, the combined influence of these expenditures within the Abuja Declaration framework remains underexplored, underscoring a critical research gap that must be addressed to guide evidence-based policymaking and promote health equity in the region.

Recent studies have provided varying perspectives on the relationship between government health expenditure and poverty reduction in sub-Saharan Africa, a topic often studied separately for out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures or public health spending.

Anyanwu and Erhijakpor (

2020) found a negative correlation, indicating that higher public investment in healthcare significantly reduces poverty by improving access to essential health services and lowering OOP expenses. Their analysis, using fixed effects and random effects models, revealed that a 1% increase in government health expenditure correlates with a 0.5% decrease in poverty rates. However, they also highlighted inefficiencies and corruption in public health spending as potential barriers to poverty alleviation, particularly in countries with weak governance structures. This underscores the importance of effective policy implementation and accountability to ensure that increased health spending effectively reduces poverty. In contrast,

Gupta et al. (

2002) identified a positive relationship between government health expenditure and poverty reduction using dynamic panel data analysis and the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) approach. They found that in certain contexts, a 1% rise in government health expenditure was associated with a 0.2% increase in poverty rates. This paradoxical finding was attributed to inefficiencies, misallocation of resources, and corruption, which hindered the efficient delivery of healthcare services, especially in countries with weak institutional frameworks. These studies highlight the critical role of governance and accountability in shaping the impact of health expenditure on poverty alleviation.

Diarra et al. (

2021) explored the impact of OOP health expenditures on poverty in Burkina Faso using propensity score matching (PSM) and regression analysis. They observed a significant negative correlation between OOP health expenditures and poverty alleviation, indicating that high healthcare costs drive households deeper into poverty. Their analysis demonstrated that households with higher OOP expenditures were 1.5 times more likely to fall below the poverty line compared to those with lower expenditures, particularly affecting vulnerable groups such as individuals with chronic illnesses or without health insurance. However, the study also noted instances where OOP spending on preventive care and effective treatments led to positive health outcomes, potentially reducing long-term healthcare costs and economic hardship (

Diarra et al., 2021).

Idris et al. (

2024) investigated the role of insurance coverage in mitigating the impact of OOP health expenditures on poverty across low- and middle-income countries. Their analysis, using regression and propensity score matching, showed that households without health insurance were more susceptible to catastrophic health expenditures, contributing significantly to poverty. Conversely, in countries with robust health insurance systems, OOP expenditures did not substantially affect poverty rates due to the protective financial coverage provided (

Idris et al., 2024). These findings underscore the dual nature of OOP health expenditures, emphasizing the need for comprehensive health insurance and effective public health policies to protect households from falling into poverty due to healthcare costs.

The combined impact of household out-of-pocket health spending and public health expenditure on poverty is critically important within the context of the 2001 Abuja Declaration. This Declaration, adopted by African Union countries, mandates that signatory nations allocate a minimum of 15% of their annual budgets to healthcare with the aim of improving health outcomes and reducing poverty. Out-of-pocket payments for healthcare disproportionately burden low-income households, exacerbating poverty through catastrophic health costs. Public health expenditure, when effectively implemented according to the Abuja Declaration, aims to alleviate these financial burdens by expanding access to affordable healthcare services and reducing out-of-pocket expenses. This strategic allocation of resources not only aims to enhance healthcare utilization but also seeks to alleviate poverty by ensuring that healthcare costs do not destabilize household economic security. By integrating principles of equity and access aligned with the Abuja Declaration’s objectives, public health expenditure can significantly contribute to addressing health inequalities and promoting sustainable development across African nations.

This study aims to examine the impact of out-of-pocket health expenditure (OOPHE) and government health expenditure (GHE) on poverty in sub-Saharan Africa over the period from 1990 to 2022. Specifically, the study seeks to:

- (i)

Investigate the long-term effects of OOPHE on poverty in sub-Saharan Africa;

- (ii)

Explore how GHE influences poverty reduction in sub-Saharan Africa;

- (iii)

Examine the interaction between OOPHE and GHE, assessing how government expenditure may reinforce or mitigate the impact of OOPHE on poverty in SSA.

The study’s contribution is particularly valuable in addressing a key gap in the existing literature on healthcare financing and poverty reduction in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). While much of the existing research focuses on the isolated impacts of either out-of-pocket health expenditure (OOPHE) or public health spending (government health expenditure, GHE), this study offers a more comprehensive approach by analyzing the combined effect of both OOPHE and GHE on poverty in SSA. By integrating these two perspectives, the study is able to highlight the nuanced and potentially conflicting impacts of healthcare financing on poverty dynamics. Furthermore, the study’s methodological rigor strengthens its contribution. The use of advanced econometric techniques, such as the

Pesaran (

2004,

2015) tests for cross-sectional dependence, the CIPS test (Cross-sectional Augmented Im, Pesaran, and Shin) for cointegration, and the Dumitrescu and Hurlin test for causality, is particularly noteworthy. These approaches allow the study to handle the complexities of panel data and country-specific heterogeneity, which are common in SSA. The application of the Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) technique, which addresses endogeneity and identifies long-run relationships, is an important methodological advance that enhances the robustness of the study’s findings.

This combination of comprehensive theoretical analysis, sophisticated empirical methods, and a focus on both public and private health spending provides new insights into how health financing policies can effectively reduce poverty in SSA. Additionally, by bridging the gap between the Abuja Declaration’s health funding targets and their impact on poverty reduction, the study offers valuable evidence for policymakers in SSA to refine strategies for health financing that are both sustainable and poverty-reducing. The findings could inform future health financing reforms and help align actual expenditure with the goals outlined in the Abuja Declaration, ultimately contributing to better health outcomes and poverty alleviation in the region. In sum, the study makes a significant contribution by filling a critical research gap, offering new empirical evidence on the joint impact of OOPHE and GHE, and employing cutting-edge econometric techniques to explore the long-term relationships between health expenditure and poverty in SSA.

Section 2 reviews the pertinent literature.

Section 3 discusses the data and econometric model. The results are presented in

Section 4, while

Section 5 provides the conclusion and policy recommendations.

6. Discussion

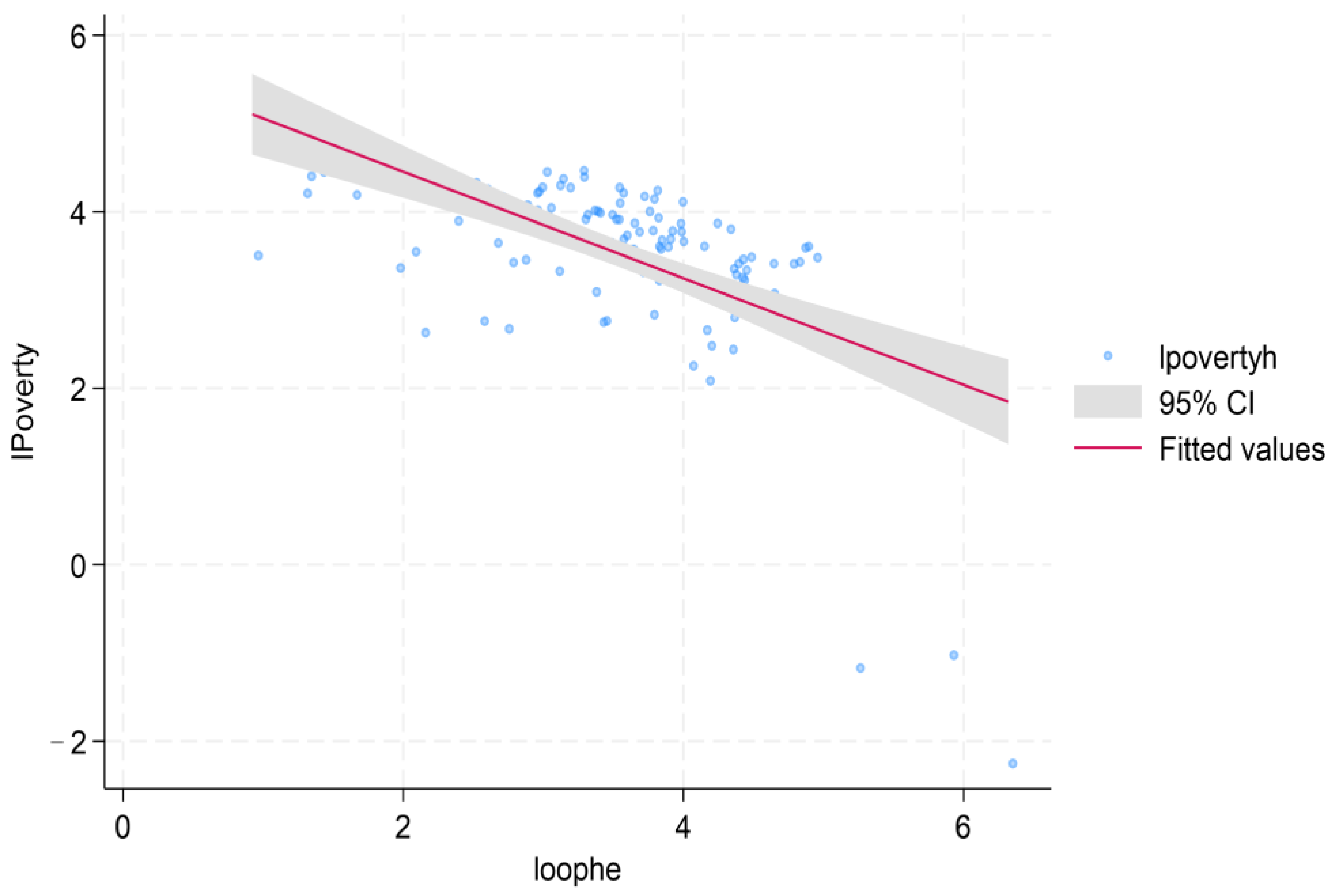

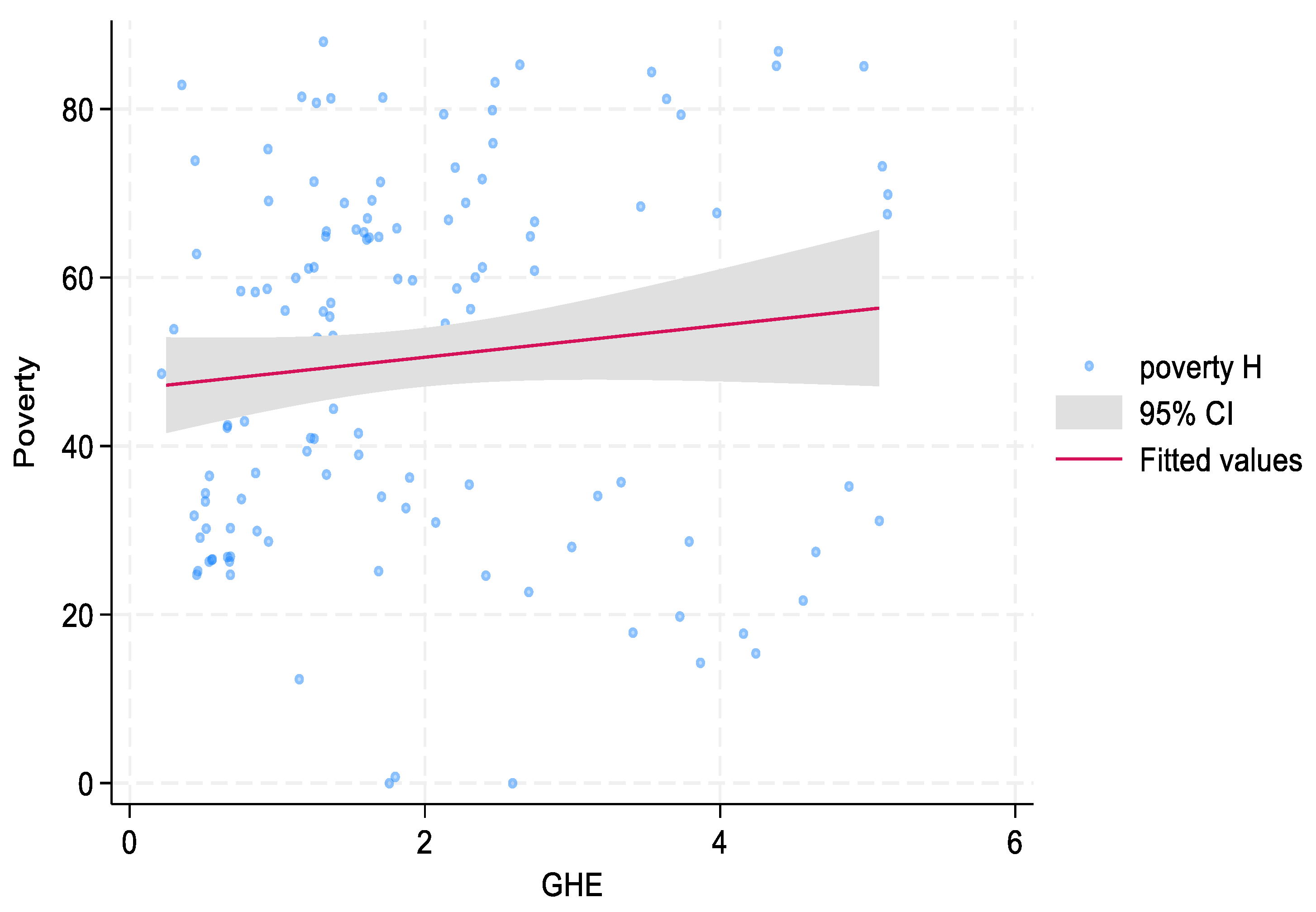

The results presented in column 2 of

Table 10 indicate that both out-of-pocket health expenditure (OOPHE) and government health expenditure (GHE) have significant positive long-run effects on poverty in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Specifically, a 1% increase in OOPHE results in a 0.051% increase in poverty, while a 1% increase in GHE leads to a 0.072% rise in poverty. These findings suggest that both private and public health expenditures are associated with increased poverty levels over time. However, the relationship between GHE and poverty is more complex than anticipated. While we expected that higher government spending on health would reduce poverty, the positive association with poverty could reflect inefficiencies in the allocation of resources within the health sector. The explanation for this relationship is not straightforward. As noted in existing literature, high government health expenditures do not always translate into better health outcomes or broader access to healthcare, particularly in regions where corruption, poor governance, and mismanagement hinder the effective use of resources (

World Bank, 2022). Therefore, the positive correlation between GHE and poverty may be driven by inefficient spending, rather than a lack of expenditure itself. This confirms the causality results. It is essential to note that GHE’s effectiveness depends on how funds are managed and directed to the most vulnerable populations. Without addressing governance challenges and ensuring targeted interventions, increased GHE may fail to alleviate poverty and could even exacerbate economic inequality. To mitigate these issues, it is essential for governments to focus on improving the governance of health systems and ensuring that health expenditures are directed toward targeted interventions that address the needs of the most vulnerable populations. Strengthening institutional frameworks to reduce corruption, enhance accountability, and improve transparency can help ensure that public health funds are used efficiently. Moreover, capacity building in health management and the establishment of robust monitoring and evaluation systems are crucial steps toward improving the effectiveness of GHE.

Gupta et al. (

2020) suggests that the targeting of health interventions is key to ensuring that increased public health spending translates into tangible benefits for the poor. Directing funds toward primary healthcare, preventive measures, and community-based healthcare programs can ensure that health services reach the poorest segments of society, thereby helping to reduce poverty. In addition, policies aimed at reducing out-of-pocket expenditures (OOPHE) can help prevent the poor from being financially burdened by healthcare costs, further alleviating poverty.

The Abuja Declaration of 2001 emphasized the need for African Union countries to allocate at least 15% of their national budgets to health to reduce reliance on OOPHE and reduce poverty. However, many SSA countries have struggled to meet this target, and the gap between actual and targeted health spending is still wide. This underscores the importance of not only increasing GHE but also improving its efficiency and targeting. Enhanced accountability, transparency, and better governance in the health sector are crucial for ensuring that public health spending leads to meaningful improvements in healthcare access and poverty reduction (

Johnson & Lee, 2019). In contrast, the FMOLS results show that OOPHE has a direct and significant impact on poverty, with a 1% increase in OOPHE leading to a 0.051% rise in poverty. This finding is consistent with the Theory of Catastrophic Health Expenditure, which posits that high out-of-pocket costs can push households into poverty by diverting financial resources away from basic needs like food and shelter. When government spending is inadequate, households are left to bear the full financial burden of healthcare, resulting in catastrophic health expenditures that exacerbate poverty. This highlights the need for comprehensive financial protection mechanisms such as health insurance or government subsidies to shield families from high health costs (

Patel & Kumar, 2021). Moreover, the bidirectional causality observed between OOPHE and poverty in

Table 5 suggests a reinforcing relationship: poverty drives increased reliance on OOPHE for healthcare, and high healthcare costs, in turn, deepen poverty. This cyclical relationship emphasizes the need for policy interventions that address both OOPHE and poverty simultaneously. For instance, reducing OOPHE could help alleviate poverty, and policies aimed at poverty reduction could also lower reliance on costly out-of-pocket healthcare (

Miller & Davis, 2020).

The interaction term between OOPHE and GHE further complicates this relationship. This term reinforces the positive association between OOPHE and poverty, suggesting that high OOPHE, coupled with low GHE, creates a significant financial burden on households. Specifically, a 1% increase in the interaction term leads to a 0.84% increase in poverty, highlighting the combined positive impact of both types of expenditures. This finding challenges Wagstaff’s 2016 argument on Healthcare Access and Utilization Theory, which posits that increased public health spending should reduce financial barriers to healthcare (

Wagstaff, 2016). In SSA, when GHE is insufficient, the increased burden of OOPHE worsens the economic strain on households. Thus, policy solutions should aim to increase public health spending and reduce reliance on OOPHE to mitigate poverty. Furthermore, the results from the FMOLS analysis suggest that external health expenditure (EHE) has a negative and significant effect on poverty, with a 1% increase in EHE leading to a 0.064% decrease in poverty in the long run. This indicates that external funding, often provided by international donors or NGOs, plays a role in improving health outcomes and reducing poverty in SSA. However, this conclusion needs to be interpreted with caution. Although EHE can support healthcare infrastructure and improve access to services, its impact on poverty is not always straightforward. In some cases, external funding can foster dependency, undermine local health systems, and result in inefficient resource allocation if not properly integrated into national health strategies (

United Nations, 2019a). The key to leveraging EHE for poverty reduction lies in effective governance, alignment with national priorities, and ensuring that resources are directed toward sustainable, locally managed health interventions. However, the impact of EHE on poverty is not always straightforward, and it is important to interpret these results with caution. While EHE can contribute to improved health infrastructure and increased access to healthcare, its long-term effectiveness is often hindered by dependency, misallocation of funds, and mismanagement. Reliance on external funding can undermine local health systems if the aid is not integrated into national health strategies. External health aid can sometimes be fragmented, with donor priorities not always aligning with the local context or national needs, leading to inefficient spending. Furthermore, over-dependence on foreign aid can weaken the sustainability of health systems by failing to build local capacity and self-reliance. If EHE is not coordinated with domestic health policies, it can result in inefficient resource allocation, particularly when funds are used for short-term solutions rather than long-term health system strengthening.

The analysis also highlights the importance of other factors in addressing poverty in SSA. Institutional quality, for example, has a positive and significant relationship with poverty, with a 1% improvement in institutional quality linked to a 0.043% increase in poverty in the long run. This finding may seem paradoxical, as better governance should ideally reduce poverty. However, it suggests that in SSA, institutional reforms may inadvertently contribute to inequality or redistribution challenges that exacerbate poverty. The relationship between governance and poverty is complex, and improving institutional quality requires addressing broader structural issues that hinder equitable development (

Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012). Information and Communication Technology (ICT) is another factor that could reduce poverty. The FMOLS results show that a 1% increase in ICT access leads to a 0.026% reduction in poverty. This suggests that ICT can play a crucial role in economic empowerment, facilitating access to markets, improving financial inclusion, and promoting education and entrepreneurship. Ensuring equitable access to ICT and developing supportive policies and infrastructure will be critical for maximizing its potential in poverty reduction (

ITU, 2021).

Educational inequality also emerges as a key driver of poverty, with a 1% increase in educational inequality leading to a 0.048% increase in poverty. This underscores the importance of addressing disparities in educational access and quality in SSA. Targeted investments in education, particularly for marginalized groups, are essential to foster human capital development and break the cycle of poverty (

UNESCO, 2020). In conclusion, the results from the FMOLS and DOLS analyses provide important insights into the complex relationships between health expenditure, poverty, and other socioeconomic factors in SSA. While both OOPHE and GHE have significant impacts on poverty, addressing the inefficiencies in health spending and ensuring that resources are targeted effectively will be crucial for mitigating poverty in the region. The roles of external funding, ICT, institutional quality, and education in poverty reduction also highlight the need for integrated, multifaceted policies to achieve sustainable development in SSA.

8. Policy Recommendations

Several policy recommendations emerge from these findings to address the negative impact of OOPHE and GHE on poverty and support the achievement of SDG-1 (poverty eradication):

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) Implementation:

Given the long-term poverty-inducing effects of OOPHE and the unintended negative relationship between GHE and poverty, implementing UHC can protect vulnerable households from catastrophic health costs. Subsidizing essential healthcare services and investing in preventive care can reduce out-of-pocket costs, thereby alleviating the financial strain on low-income populations.

Optimize Government Health Expenditure:

While GHE is expected to reduce poverty, the results suggest inefficiencies in its utilization. Therefore, optimizing GHE through improved governance, transparency, and the reduction of inefficiencies is crucial. Resources should be targeted to the most vulnerable populations to improve healthcare access and reduce financial barriers. Additionally, healthcare infrastructure should be strengthened, particularly in underserved areas, to ensure equitable access to services.

Strengthen Health Insurance Systems:

Expanding and improving health insurance systems can protect households from the economic impact of health expenditures. Ensuring broader coverage and better targeting of subsidies to low-income households would reduce the reliance on OOPHE and mitigate its effects on poverty.

Invest in Human Capital Development:

Investing in education and training for healthcare professionals, particularly in rural and underserved areas, will improve healthcare delivery. Incentivizing the retention of healthcare workers in these areas will ensure that healthcare services are accessible to more populations, reducing disparities in healthcare access.

Governance and Institutional Reforms:

As noted in the study’s results, weak governance and institutional frameworks may contribute to the ineffective use of public health expenditure, which exacerbates poverty. Strengthening accountability and transparency within the health sector, including addressing issues of corruption and resource misallocation, is essential. Effective institutional reforms will improve resource allocation, reduce inefficiencies, and ensure that health spending benefits the most vulnerable populations.

External Health Expenditure Optimization:

While the study shows that external health expenditure (EHE) has a negative effect on poverty, it remains a critical source of funding for health in SSA. However, the impact of external funding is only effective when directed towards building sustainable infrastructure and addressing critical healthcare gaps. Optimizing external health investments by ensuring alignment with national health priorities and improving governance around aid management will increase the effectiveness of these resources.

Domestic Resource Mobilization:

Increasing domestic funding for health through improved tax collection, fiscal reforms, and innovative financing mechanisms can reduce dependency on external funding, providing a more sustainable solution to health financing challenges in SSA. These measures will help strengthen national health systems and provide more equitable access to healthcare.

Integrated Development Approaches:

Health outcomes are strongly influenced by broader development factors such as education, economic empowerment, and infrastructure. Policy interventions should be designed to integrate health with other key development goals, such as improving access to education, reducing inequality, and fostering economic growth. Such integrated approaches will help mitigate the impact of healthcare costs on poverty.

Monitoring, Evaluation, and Resilience Building:

Establishing robust monitoring and evaluation frameworks to track the effectiveness of health and poverty-related policies will help identify successful strategies and areas for improvement. Additionally, strengthening health system resilience, especially against economic shocks and health emergencies, is crucial. SSA countries should invest in preparedness and contingency planning to safeguard healthcare systems and reduce their vulnerability to crises.

In conclusion, the findings of this study highlight the critical importance of effective health expenditure management and targeted policy interventions to mitigate the long-term impact of OOPHE and GHE on poverty. Policymakers in SSA should prioritize universal health coverage, optimize government health expenditure, strengthen health insurance systems, and address governance and institutional challenges to create a more equitable and sustainable healthcare system that contributes to poverty reduction.