The Labour Market in Kazakhstan Under Conditions of Active Transformation of Their Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

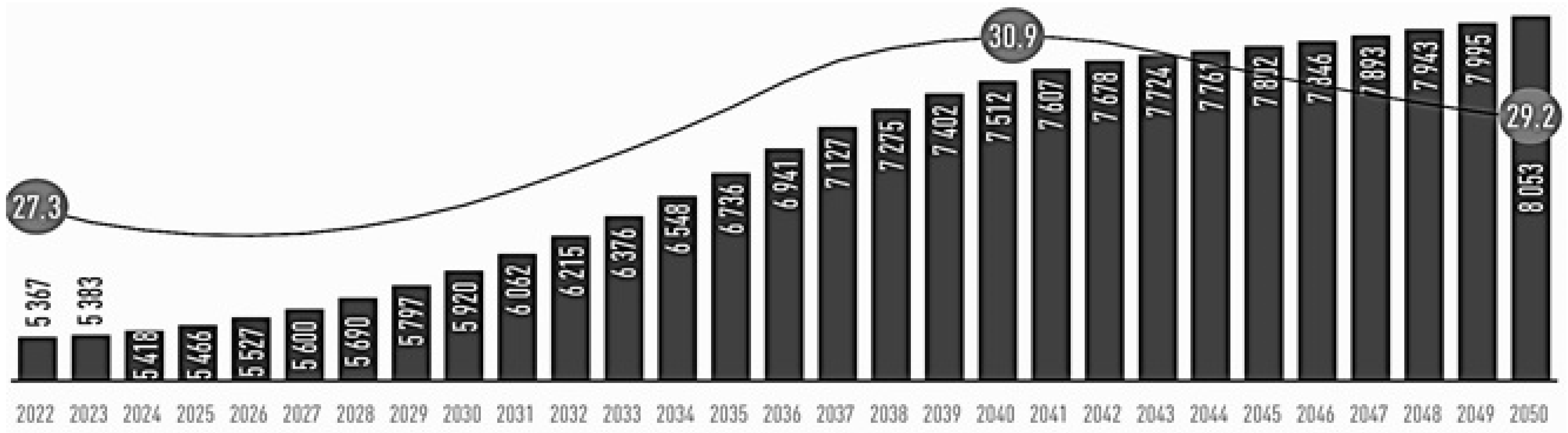

Demographic ageing of the population

Economic shocks caused by crises and natural disasters

Innovation and technological change

External and internal migration

Gender policies

Job role transformation, changing skill requirements, and complex wage dynamics

Trade union participation

The growth of entrepreneurship

2. Methodology

3. Results

- Labour force (LF)—the size of the population participating in labour activity.

- Employment (E)—the number of employed persons.

- Unemployment (U) is the number of people actively looking for work but cannot find it.

- Unemployment rate (UR) is the share of unemployed people in the labour force.

- Youth unemployment rate (YUR) is the percentage of unemployed youth.

- Gross domestic product per capita (GDPpc) indicates economic well-being.

- External migration (NM) is the balance of migration flows that affect demographic and labour potential.

- Economically active population (EA) is the share of the population involved in economic activity.

- Test for autocorrelation of residuals (Ljung–Box Test).

- 2.

- Jarque–Bera test for normality of residuals.

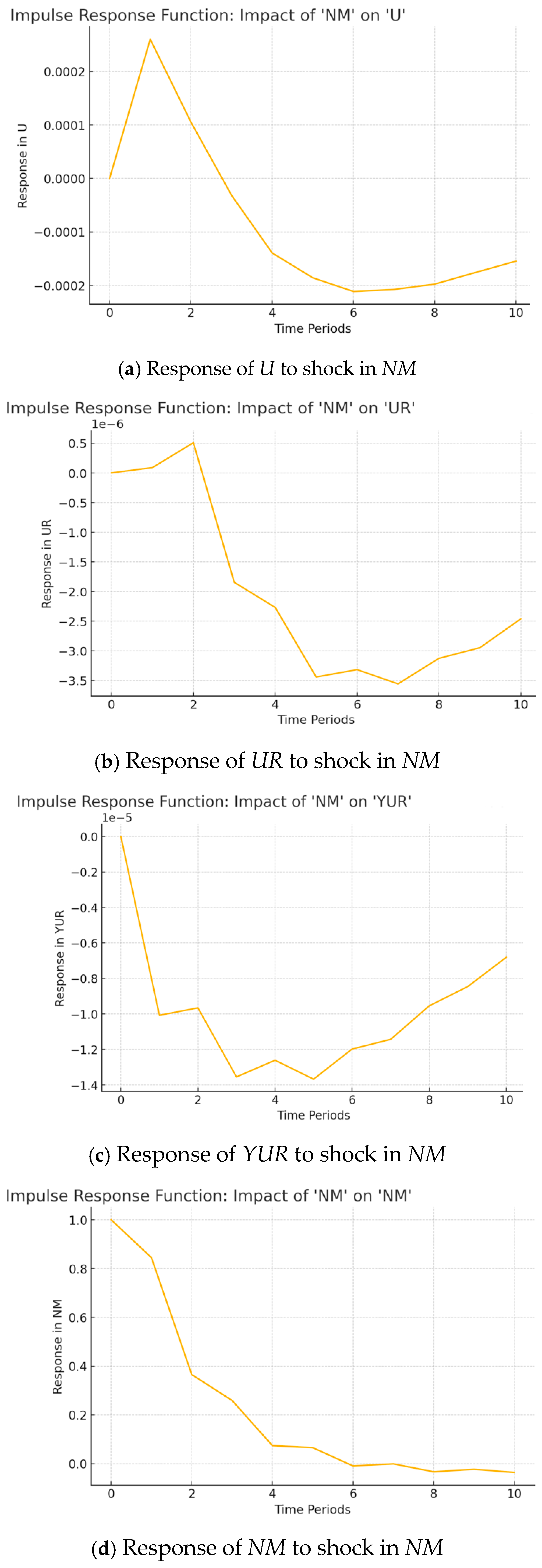

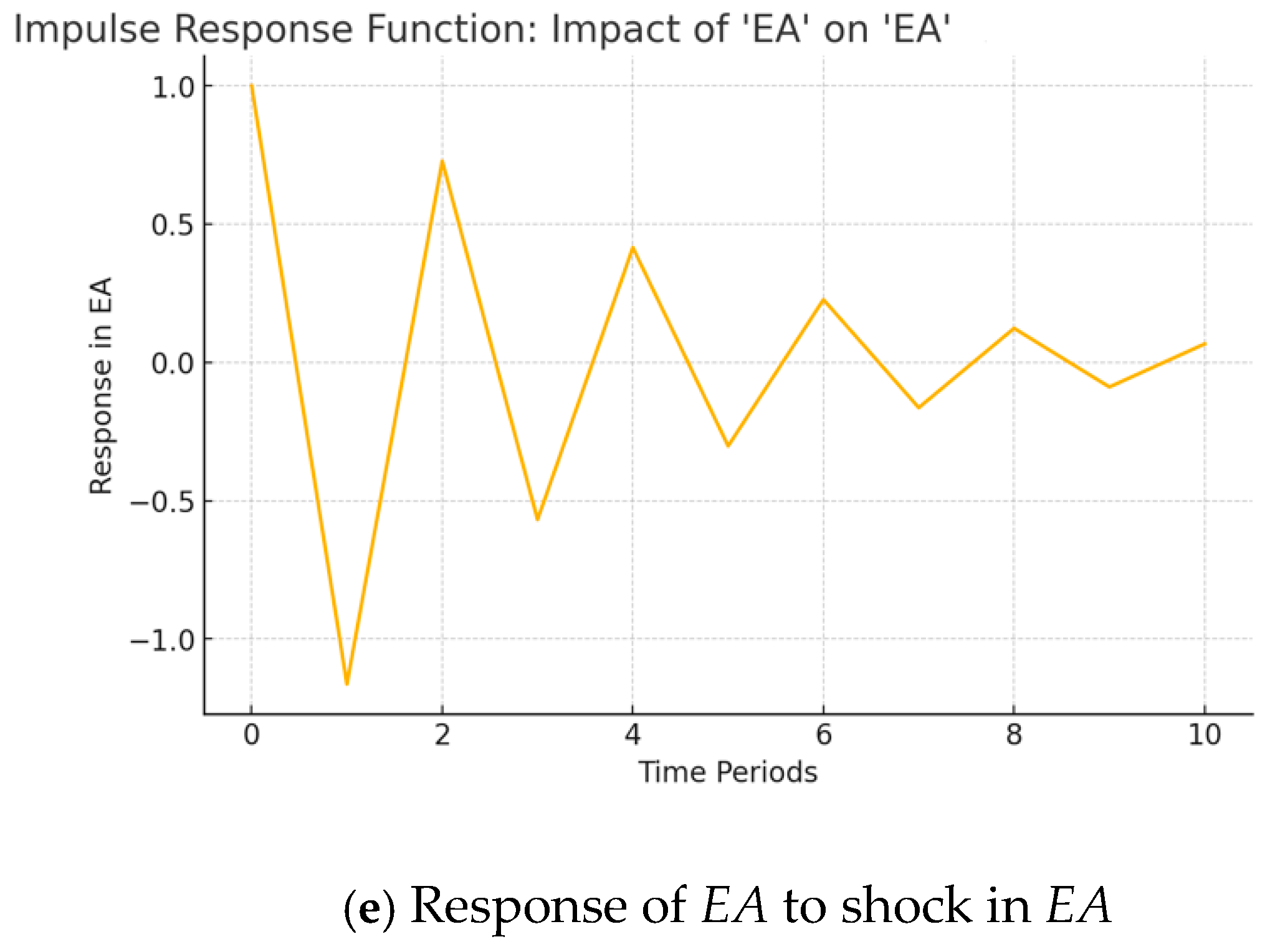

- The direction of the impact: whether the value of the variable increases or decreases in response to the shock.

- The strength of the impact: how much the value of the variable changes.

- The duration of the impact: how many periods before the effect of the shock disappears.

- Relationships between variables.

- Strong relationships: the variables U, UR, and YUR are closely related. Shocks in one of these variables quickly trigger significant responses in the others.

- 3.

- Dynamics of shocks

- 4.

- Practical implications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdramanova, U., Nietalina, G., Orlowska, R., & Spanov, M. (2024). The economic consequences of youth migration in Kazakhstan: An analysis of the loss of human capital. Bulletin of “Turan” University, 4, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency of the Republic of Kazakhstan on Statistics. (2011). Population migration: Results of the national population census of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz/en/industries/social-statistics/demography/publications/79244/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Alba, R., & Foner, N. (2016). Integration’s challenges and opportunities in the Wealthy West. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshanskaya, A. (2024). Youth in the labour market in Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://kisi.kz/ru/molodezh-na-rynke-truda-v-kazahstane/ (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Aminov, I. A., & Aminov, F. I. (2024). Influence of business development on employment in the Sughd region of the Republic of Tajikistan. Bulletin of the Tajik State University of Commerce, 2(52), 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ariansyah, K., Wismayanti, Y. F., Savitri, R., Listanto, V., Aswin, A., Ahad, M. P. Y., & Cahyarini, B. R. (2024). Comparing labour market performance of vocational and general school graduates in Indonesia. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baikulakov, S. (2023). Workforce of the future: Youth in the labour market of Kazakhstan. Ministry of Labour and Social Protection of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://erdo.enbek.kz/storage/news_files/%D0%9D%D0%B0%D1%86%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B4%20%D1%80%D1%83%D1%81%D1%81.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Bardhan, P., & Mookherjee, D. (2006). Decentralisation and local governance in developing countries: A comparative perspective. The World Bank Research Observer, 21(2), 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, D., Wagner, G., & Araki, M. (2024). Labour market reform as an external enabler of high-growth entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 39(6), 106428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasques, F., Hoogerkamp, M. H., Jan Koopman, S., & van de Werve, I. (2021). Dynamic factor models with clustered loadings: Forecasting education flows using unemployment data. International Journal of Forecasting, 37(4), 1426–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunerhjelm, P., Eklund, J., & Kugler, M. (2023). Labour market regulations, innovation and technological change. In Handbook of innovation and regulation. Available online: https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/gbp/eelgar/product_flyer/printpage/id/20532/ (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Bureau of National Statistics. (2023). Migration of the population of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz/en/industries/social-statistics/demography/publications/157661/ (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Bureau of National Statistics. (2024). On the demographic situation for January–December 2024. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz/ru/news/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Carneiro, P., Dearden, L., & Vignoles, A. (2010). The economics of vocational education and training. In International encyclopedia of education. Semantic Scholar. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedefop. (2017). Cedefop European public opinion survey on vocational education and training. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/575587 (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Education in the Republic of Kazakhstan. (2021). Population Census 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz/en/national/2021/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Harding, L., & Neamtu, M. (2018). Dynamic model of unemployment with migration and delayed policy intervention. Computational Economics, 51, 427–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W., Zhang, B., & Zhang, J. (2024, January 12–14). The impact of technology on the labor market: An analysis of the changing landscape. 9th International Conference on Financial Innovation and Economic Development (ICFIED 2024), Ningbo, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, J., & Chen, H. (2015). Statistical mechanics of human resource allocation. Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics, 146, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I., Xue, J., Zaman, S., & Mehmood, Z. (2022). Nexus between FDI, economic growth, industrialisation, and employment. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 14(3), 3153–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L. R. (2013). Mathematical economics: An introduction to the economic analysis. Journal of Economic Literature, 51(4), 1234–1236. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczera, M., & Jeon, S. (2019). Vocational education and training in Sweden. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, A., & Singh, A. (2011). A mathematical model for unemployment. Nonlinear Analysis: Real World Applications, 12, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Sanguinetti, J., & Atienza-Maeso, A. (2024). How effective is equality regulation in reducing gender gaps? Journal of Policy Modelling, 46, 823–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhitdinova, S. (2024). Peculiarities of the regulation of employment of the population in the Union of Independent States countries. Fundamental Research, 10, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- One-Third of Kazakhstani Citizens Have Informal Employment. (2024). Available online: https://ranking.kz/digest/industries-digest/tret-rabotayuschih-kazahstantsev-imeyut-neformalnuyu-zanyatost.html (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Ostapchuk, A., Kustrich, L., Tranchenko, L., Botsula, O., Kolmakova, V., & Patoka, I. (2021). Modeling the labor market stability in conditions of uncertainty. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, 194, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyarzo, M., & Ferrada, L. (2024). Exploring the impact of employment policies on wages and employability. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 16, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhomenko, N. (2024). Trends of labour migration. Economy and Marriage, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliament of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (2015). Labour code of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/K1500000414 (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Rakhmetova, A., & Syzdykbekov, E. (2024). Modern trends of external labour migration in Kazakhstan. Practice, 2024, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (2023). Approval of the concept of labour market development is required. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P2300001050 (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Rigolini, I., Sanchez-Reaza, J., Shulga, I., Ustinova, M., Baikulakov, S., Shumekov, D., & Shegenova, U. (2024). More, better and inclusive jobs in Kazakhstan. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Rollnik-Sadowska, E., & Bartkute-Norkuniene, V. (2024). The efficiency of labour market policies in EU countries. Comparative Economic Research Central and Eastern Europe, 27(2), 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shananin, A., & Trusov, N. (2023). Mathematical modeling of the household behavior in the labor market. Mathematical optimisation theory and operations research. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagulova, G., & Barzhaksyyeva, A. (2024). State regulation of employment in Kazakhstan: Labour market and ways of development. Economy: Strategy and Practice, 19(3), 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syzdykbekov, E. (2022). External labor migration as a factor in the development of the labor market in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Bulletin of Karaganda University “Economics”, 4(108), 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasyev, A. (2017). The gravity model of labor migration behavior. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1863, 560062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textor, C. (2024). Economic slowdown—Impact on the labour market. In Economy & politics/economy. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/239153/employment-rate-in-china/ (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- The Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan. (2023). Resolution ‘On approval of the concept of labour market development of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2024—2029’. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P2300001050#z59 (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Turtaeva, M. (2024). “The perfect storm”: The labor market in Kazakhstan in 2024. Workforce. Available online: https://manpower.kz/media/publication/%C2%ABidealnyij-shtorm%C2%BB-ryinok-truda-kazaxstana-v-2024-godu.html (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Vézina, S., & Bélanger, A. (2020). Literacy skills as an explanation for labour market imbalances by occupational type in Canada: Microsimulation projections for 2014–2024. Population Research and Policy Review, 39, 1019–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyaoui, M., & Amine, S. (2024). Mathematical modelling of unemployment dynamics with skills development and cyclical effects. Partial Differential Equations in Applied Mathematics, 11, 100800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeleseyeva, E. (2024). Zhakupova named the problems of the labour market of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://www.zakon.kz/obshestvo/6452292-problemy-rynka-truda-kazakhstana-nazvala-zhakupova.html (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Zambrano-Monserrate, M. (2024). Labour dynamics and unions: An empirical analysis through Okun’s Law. Economic Analysis and Policy, 82, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarifhonarvar, A. (2024). Economics of Chatgpt: A labour market view on the occupational impact of artificial intelligence. Journal of Electronic Business & Digital Economics, 3, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhumashbekova, S., Kirdasinova, K., Talapbayeva, G., Bekmagambetova, G., Nurpeissova, A., Orynbekova, G., & Aldeshova, S. (2024). Assessment of the migration processes on the example of Kazakhstan. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 16, 12645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Years | Total, Millions of People | Percentage With a Level of Education | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher Education | Incomplete Higher Education | Secondary Special Education | Overall Average Education | Basic Secondary Education | Primary Education | ||

| The Entire Population, Millions of People | |||||||

| 2009 | 12.2 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 1.6 | 0.6 |

| 2021 | 13.5 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

| The Entire Population, % | |||||||

| 2009 | 100 | 19.8 | 3.1 | 27.6 | 30.9 | 13.3 | 4.9 |

| 2021 | 100 | 27.6 | 1.6 | 30.8 | 26.6 | 9.8 | 3.4 |

| Years | Total, Millions of People | Those Who Have Education, People per 1000 Inhabitants of the Country | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher Education | Incomplete Higher Education | Secondary Special Education | Overall Average Education | Basic Secondary Education | Primary Education | ||

| 2009 | 12.2 | 198 | 31 | 276 | 309 | 133 | 49 |

| 2021 | 13.5 | 276 | 16 | 308 | 266 | 98 | 34 |

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republic of Kazakhstan | −12,162 | −13,466 | −21,145 | −22,130 | −29,121 | −32,970 | −17,718 | −21,217 | −6722 | 9293 |

| Abay | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −660 | −393 |

| Akmola | −1497 | −1050 | −1593 | −2231 | −2148 | −2801 | −1738 | −1768 | −1149 | −730 |

| Aktobe | −191 | −606 | −713 | −1071 | −1261 | −1899 | −1336 | −1476 | −580 | 43 |

| Almaty | 419 | 1833 | 2210 | 3753 | 542 | 767 | −145 | −1163 | 1011 | 1196 |

| Atyrau | 370 | 219 | 238 | 185 | 36 | −68 | −2 | 112 | 237 | 500 |

| West Kazakhstan | −565 | −731 | −526 | −786 | −1206 | −1606 | −1005 | −836 | −393 | 582 |

| Zhambyl | −142 | −434 | −626 | −479 | −449 | −946 | −838 | −1041 | −651 | −513 |

| Zhetisu | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −314 | 82 |

| Karaganda | −3403 | −3874 | −5483 | −5571 | −5255 | −5388 | −3771 | −4349 | −2373 | −687 |

| Kostanay | −2260 | −2388 | −3692 | −4169 | −4820 | −4665 | −2542 | −2635 | −1933 | 108 |

| Kyzylorda | 19 | −45 | −51 | −27 | −35 | −38 | −8 | −61 | −21 | −42 |

| Mangistau | 2091 | 2791 | 1381 | 1087 | 1114 | 1965 | 2450 | 2212 | 3336 | 3416 |

| Pavlodar | −2370 | −2966 | −3974 | −3888 | −4173 | −5298 | −2788 | −2855 | −1858 | −380 |

| North Kazakhstan | −2671 | −2099 | −2533 | −2651 | −3210 | −3660 | −1759 | −1863 | −1181 | −183 |

| Turkestan | 1382 | 593 | 501 | 754 | 336 | −24 | 500 | 252 | 314 | 352 |

| Ulytau | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −201 | −146 |

| East Kazakhstan | −3122 | −3511 | −3712 | −4306 | −5582 | −6515 | −3335 | −3650 | −1804 | −979 |

| Astana city | 375 | −25 | −636 | −926 | −1276 | −1068 | −742 | −1000 | 39 | 1461 |

| Almaty city | −597 | −1173 | −1936 | −1804 | −2096 | −2219 | −960 | −1352 | 1226 | 5097 |

| Shymkent city | - | - | - | - | 362 | 493 | 301 | 256 | 233 | 509 |

| Years | Total, Millions of People | Those Who Have Education, People per 1000 Inhabitants of the Country | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher Education | Incomplete Higher Education | Secondary Special Education | Overall Average Education | Basic Secondary Education | Primary Education | ||

| 2009 | 3031.9 | 591.7 | 122.3 | 58.8 | 597.7 | 432.9 | 275.5 |

| 2021 | 2770.5 | 705.2 | 37.5 | 183.2 | 449.3 | 252.8 | 211.6 |

| Indicators | Total | Including | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Population | Rural Population | ||||||||

| Both Sexes | Including | Both Sexes | Including | Both Sexes | Including | ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | ||||

| Unemployed population, total | 445,886 | 200,478 | 245,408 | 276,802 | 123,822 | 152,980 | 169,084 | 76,656 | 92,428 |

| At the age of | |||||||||

| 15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 16–24 | 38,090 | 18,692 | 19,398 | 24,112 | 10,900 | 13,212 | 13,978 | 7792 | 6186 |

| 25–28 | 26,233 | 11,493 | 14,740 | 13,570 | 5514 | 8056 | 12,663 | 5979 | 6684 |

| 29–34 | 58,657 | 25,684 | 32,973 | 40,096 | 17,297 | 22,799 | 18,561 | 8387 | 10,174 |

| 35–44 | 158,353 | 68,256 | 90,097 | 101,537 | 45,284 | 56,253 | 56,816 | 22,972 | 33,844 |

| 45–54 | 99,189 | 44,695 | 54,494 | 61,174 | 27,913 | 33,261 | 38,015 | 16,782 | 21,233 |

| 55–64 | 65,364 | 31,658 | 33,706 | 36,313 | 16,914 | 19,399 | 29,051 | 14,744 | 14,307 |

| 65 and older | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Including those of working age | 444,854 | 200,406 | 244,448 | 276,443 | 123,780 | 152,663 | 168,411 | 76,626 | 91,785 |

| Variable | ADF Statistic | p-Value | Stationary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labour force, thousands of people (LF) | −0.0757 | 0.9518 | False |

| Employed population, thousands of people (E) | −0.4859 | 0.8947 | False |

| Unemployed population, thousands of people (U) | −4.0057 | 0.0014 | True |

| Unemployment rate, % (UR) | −3.8728 | 0.0022 | True |

| Youth unemployment rate, % (YUR) | −4.5799 | 0.0001 | True |

| GDPpc, KZT (GDPpc) | 2.1166 | 0.9988 | False |

| External migration, balance (NM) | −5.8480 | −3.6407 | True |

| Economically active population, thousands of people (EA) | −3.6100 | 0.0056 | True |

| Variable | Unemployed Population, Thousands of People (U) | Unemployment Rate, % (UR) | Youth Unemployment Rate, % (YUR) | External Migration (Balance) (NM) | Economically Active Population, Thousands of People (EA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| const | 333.8475 | 2.398 | −0.5653 | 104,870.8141 | 3203.8523 |

| Unemployed population, thousands of people (U) | 0.2098 | −0.0025 | 0.0105 | −180.2855 | 11.2933 |

| Unemployment rate, % (UR) | −5.0705 | 0.3802 | −1.4417 | 11,622.9049 | −640.4511 |

| Youth unemployment rate, % (YUR) | 14.9310 | 0.2200 | 1.1386 | 781.0184 | −28.6544 |

| External migration (balance) (NM) | 0.0003 | 0.00000008 | −0.00001 | 0.8447 | 0.0076 |

| Economically active population, thousands of people (EA) | −0.0024 | 0.0004 | 0.0010 | −38.6191 | −1.1631 |

| Variable | LB Statistic | p-Value | No Autocorrelation (p > 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployed population, thousands of people (U) | 0.5649 | 0.4523 | Yes |

| Unemployment rate, % (UR) | 1.0846 | 0.2977 | Yes |

| Youth unemployment rate, % (YUR) | 0.0438 | 0.8342 | Yes |

| External migration (balance) (NM) | 0.4557 | 0.4996 | Yes |

| Economically active population, thousands of people (EA) | 0.1940 | 0.6596 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beisembina, A.; Abuselidze, G.; Nurmaganbetova, B.; Kabakova, G.; Makenova, A.; Nurgaliyeva, A. The Labour Market in Kazakhstan Under Conditions of Active Transformation of Their Economy. Economies 2025, 13, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050131

Beisembina A, Abuselidze G, Nurmaganbetova B, Kabakova G, Makenova A, Nurgaliyeva A. The Labour Market in Kazakhstan Under Conditions of Active Transformation of Their Economy. Economies. 2025; 13(5):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050131

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeisembina, Ansagan, George Abuselidze, Begzat Nurmaganbetova, Gulnur Kabakova, Aigul Makenova, and Ainash Nurgaliyeva. 2025. "The Labour Market in Kazakhstan Under Conditions of Active Transformation of Their Economy" Economies 13, no. 5: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050131

APA StyleBeisembina, A., Abuselidze, G., Nurmaganbetova, B., Kabakova, G., Makenova, A., & Nurgaliyeva, A. (2025). The Labour Market in Kazakhstan Under Conditions of Active Transformation of Their Economy. Economies, 13(5), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050131