Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a field of strategic interest for both the European Union (EU) and its member states, which are making significant efforts to develop and implement AI in a way that is economically and socially beneficial, as well as ethical and secure. This paper analyzes the importance of AI and its impact on the economy and society, highlighting the strategic and regulatory aspects agreed upon at the EU and Romanian levels, given this state’s status as an EU member. Based on the latest specialized literature, the first part addresses the concept of AI and emphasizes its role as a key driver of innovation and economic growth. Subsequently, we examine the EU’s institutional concerns, outlining the key guidelines and steps in harnessing AI opportunities, as well as the strategic and regulatory milestones that govern AI implementation within the EU. In this context, we focus on the complexities involved in the transition to the AI Era, recent developments, the process of drafting and adopting the EU AI Act, and the significance of the AI Pact. Our study fully reflects that Romania is also taking significant strategic and regulatory measures to align with the demands of the AI Era, with particular attention given to improving the legislative framework regarding the ethical implications of AI implementation and preventing deepfakes.

1. Introduction

The AI Era refers to a period of technological development in which artificial intelligence becomes a central and transformative component in nearly all aspects of human life, from the economy and labor markets to international relations and everyday life. This era is characterized by the rapid and widespread integration of AI-based technologies across various fields, leading to significant changes in how people live, work, and interact with the world around them.

The main features of the AI Era cover a broad spectrum, from advanced automation—where AI enables not only the automation of repetitive tasks but also those requiring complex thinking, such as medical diagnostics, financial analysis, and decision-making in critical situations—to the expansion of human cognitive and creative capacities, offering new opportunities for innovation and solving complex problems, to global and geopolitical implications. AI is an important technology with the potential to deliver significant benefits to citizens, businesses, and society as a whole, provided it is developed responsibly, with a human-centered approach that respects ethical principles and sustainability. AI development must be guided by respect for fundamental rights and the core values of society. AI has the ability to boost productivity and efficiency, thus enhancing the competitiveness of the European economy and improving quality of life.

Additionally, AI can play a vital role in addressing major global challenges such as climate crises, environmental degradation, and demographic shifts. It can also contribute to protecting democracy and, where necessary and justified, combating crime, while ensuring a balance between security and citizens’ freedoms (EC, 2020a).

This geopolitical dynamic is further fueled by the race among nations to become leaders in AI, as supremacy in AI is expected to confer significant strategic advantages in the fields of economics, security, and diplomacy.

AI is a powerful driver of economic growth and innovation, yet it comes with major challenges in important areas such as ethics, privacy, and reducing social inequalities.

A relevant example is the phenomenon of deepfakes, which demonstrates that as technology becomes increasingly advanced and accessible, the risks associated with creating digitally falsified content grow considerably. This trend highlights the need to develop effective methods for detecting deepfakes and raising public awareness of these threats. Current research focuses on developing AI algorithms capable of identifying deepfakes, which involve sophisticated techniques for manipulating images and videos to create false content (NCD, 2023). These algorithms analyze highly subtle details that are difficult for the human eye to detect, such as anomalies in eye movement or skin texture.

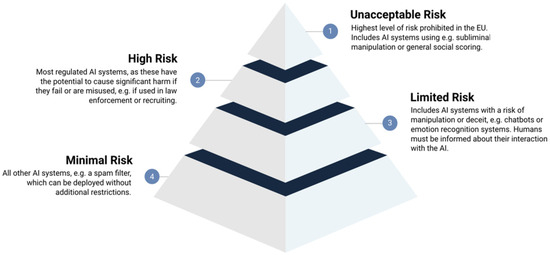

In the face of these challenges, international legislation is beginning to evolve. For example, the European Parliament (EP) has adopted Regulation COM/2021/206 on AI, which aims to protect fundamental rights, democracy, and the environment. The regulation classifies AI systems based on their risk levels—from unacceptable to minimal—and prohibits certain dangerous practices, such as behavioral manipulation of vulnerable individuals or real-time biometric identification. Moreover, this legislative framework addresses the issue of deepfakes, imposing transparency and accountability requirements.

AI systems with unacceptable risk are completely banned, those with high risk must be clearly labeled, and those with minimal or limited risk are not subject to specific restrictions. Deepfake providers are required to inform users about the artificial nature of the content, and online platforms must implement effective measures to prevent the spread of harmful content.

Referring to Romania, we note that there has been progress in AI regulation, in line with European initiatives in this field. A significant step in this process was the adoption of NAIS, which sets the main directions for the development and implementation of this technology. The strategy aims to create an environment conducive to innovation, support the development of digital infrastructure, and integrate AI into important areas such as public administration, healthcare, cybersecurity, and the digital economy. At the same time, the document emphasizes the need to align with the ethical and transparency standards promoted by the EU.

An important aspect of the strategy focuses on improving the national regulatory framework to ensure a clear set of rules regarding the use and development of AI. In this regard, we discuss the AI Law, which refers to establishing ethical principles, transparency requirements, and rules for classifying AI systems based on their risk levels, aiming to ensure the safe and responsible use of technology while preventing abuses and negative effects on society. Additionally, we address a legislative initiative—closely related to the theme of our work—that aims to combat the deepfake phenomenon, in the context of growing concerns regarding disinformation, political manipulation, and digital fraud. In this regard, measures are being considered to mandate the clear labeling of artificially generated content, sanctions for its fraudulent use, and technological solutions for detecting and removing deepfakes.

We emphasize that our paper predominantly addresses the regulatory aspects of AI. In terms of achieving our goal—deepening the complex strategic and regulatory preparations required for the transition to the AI Era, with reference to Romania as a member state of the European Union (EU), and all the constraints and consequences that come with this status—we have chosen to structure our work in a highly specific manner.

Thus, the paper includes an introduction in Section 1, followed by Section 2: AI—Concept and Importance for the Economy and Society, and Section 3: Institutional Concerns in the EU Regarding AI Issues, with Section 3.1 expanding on goals and milestones for maximizing AI opportunities, and Section 3.2 on the strategic and regulatory benchmarks for AI implementation in the EU, including certain analytical approaches (Section 3.2.1 describes the characteristics of the AI strategic framework in the EU; Section 3.2.2 delves into developments following the implementation of the EU AI strategic framework; Section 3.2.3 expands on the drafting and adoption of the EU AI Act; and Section 3.2.4 focuses on the AI Pact). Section 4—Preparations of a strategic and normative nature by Romania for the AI Era—includes Section 4.1: Romania’s Adoption of the NAIS, and Section 4.2: Enhancing/Improving the National Regulatory Framework (further details are given in Section 4.2.1: Drafting an AI Law—The Coordinates for Regulation, Implementation, Use, Development, and Protection of AI in Various Environments, and Section 4.2.2: Legislative Attempts to Prevent the Deepfake Phenomenon). The paper concludes with Section 5: Conclusions, where we also suggest future research directions stemming from the current study’s results.

We believe that the interest in this work may be very high—both in the academic community and practitioners (entrepreneurs or managers)—as, after addressing AI from conceptual perspectives and its importance for the economy and society, it seeks to provide well-founded answers to the following questions:

Q1: What are the institutional concerns in the EU regarding AI issues?

Q2: What are the strategic and regulatory benchmarks for AI implementation in the EU, including certain analytical approaches?

Q3: What developments have occurred following the implementation of the EU AI strategic framework?

Q4: What is the context for the drafting and adoption of the EU AI Act and AI Pact, from Romania’s strategic and normative plans for the AI Era to legislative efforts to prevent the deepfake phenomenon?

Moreover, we note that works with such content are quite limited in the currently available specialized literature. As the title of this paper suggests, our main focus is on the complex preparations undertaken by the Romanian state, both strategic and legislative, necessary for transitioning to the “AI Era”. However, we also pay special attention to the most important institutional and regulatory concerns and efforts at the EU level regarding AI issues.

Regarding the author’s analytical and conceptual contribution, as well as the practical relevance of the formulated conclusions, we note that we have conducted a thorough analysis of the concept of AI and its importance for the economy and society, providing a clear framework for understanding the implications of this technology. The key orientations and stages in the development of European AI strategies have been addressed in connection with EU regulations and initiatives, including the adoption of the AI Act and AI Pact. An important contribution of the author lies in evaluating how Romania is adapting to the AI Era through the NAIS and the development of a specific regulatory framework.

By examining the deepfake phenomenon and prevention measures, we believe we have tackled a highly relevant topic, analyzing Romania’s legislative and strategic efforts to combat deepfakes, while highlighting both challenges and opportunities. The conclusions offered are considered pertinent to strengthening AI’s role in the economy and society, while also emphasizing the need for a balance between innovation and regulation.

2. AI—Concept and Importance for the Economy and Society

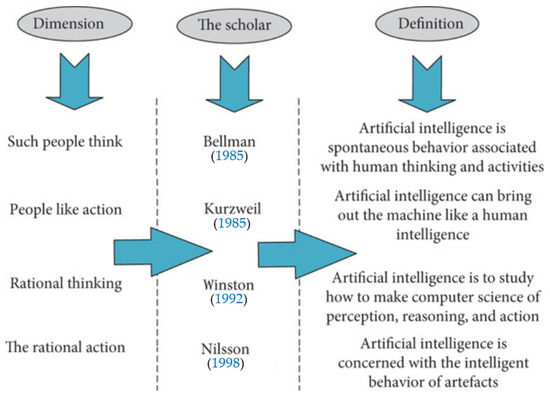

Over the past half-century, several concepts and ideas regarding AI have crystallized in the specialized literature. First, in the context of defining and explaining its purpose, AI refers to the ability of machines to perform tasks that would require human intelligence (Rughinis, 2022; Sfetcu, 2021; Kaplan, 2016).

Intelligence can also be defined as a robot’s ability to learn and apply appropriate techniques to solve problems and achieve goals suitable to the context in uncertain, ever-changing situations (Manning, 2020). The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development defines AI as “a machine-based system that can, for a given set of human-defined objectives, make predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing real or virtual environments” (OECD, 2019).

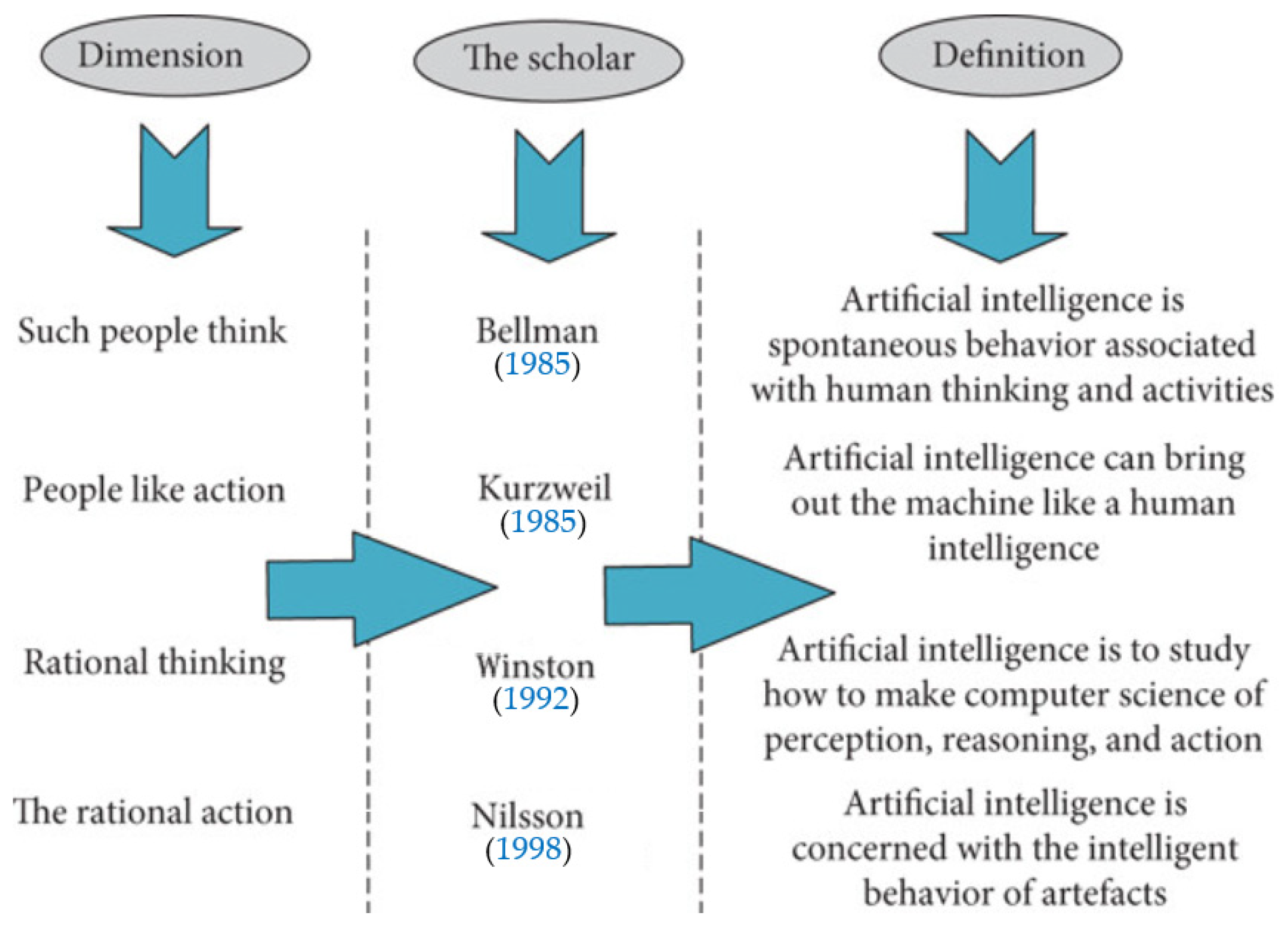

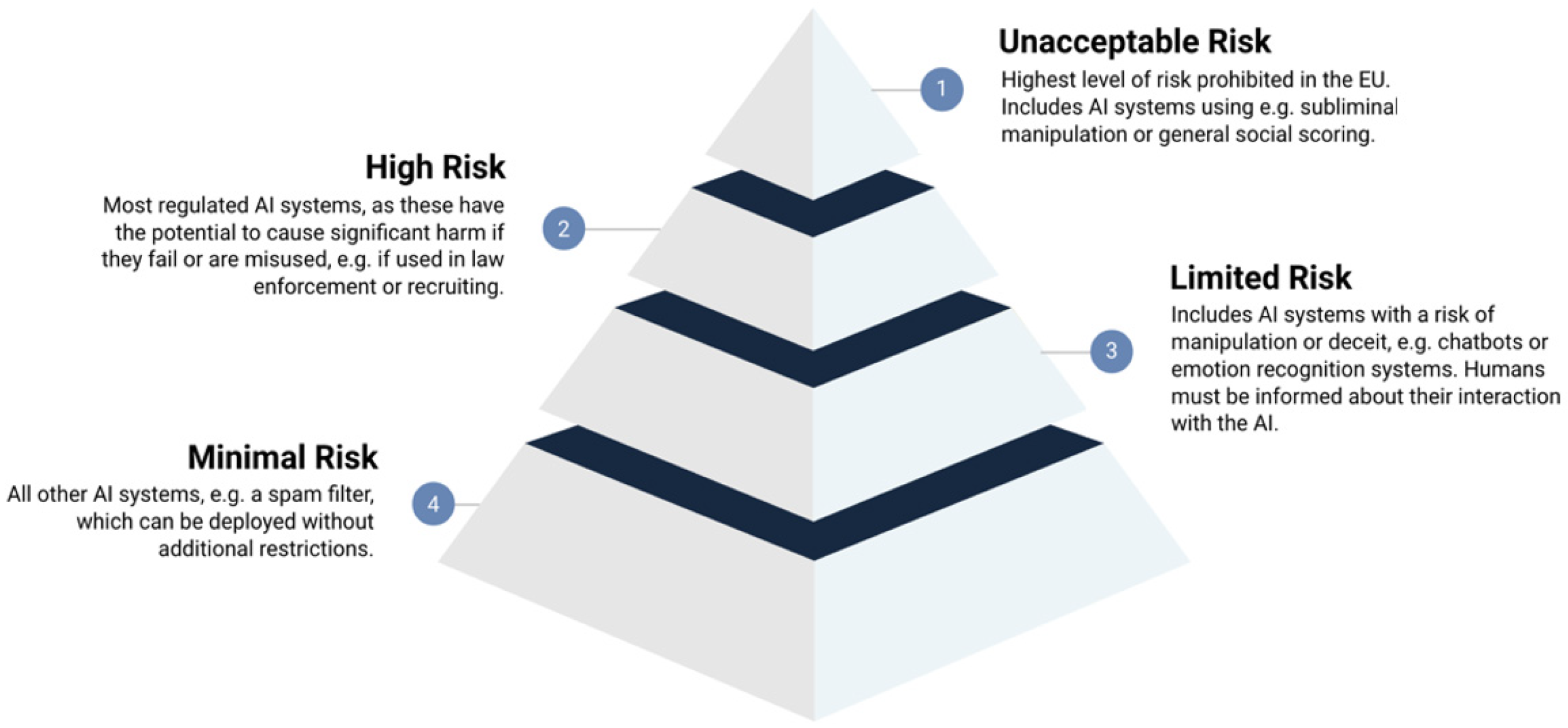

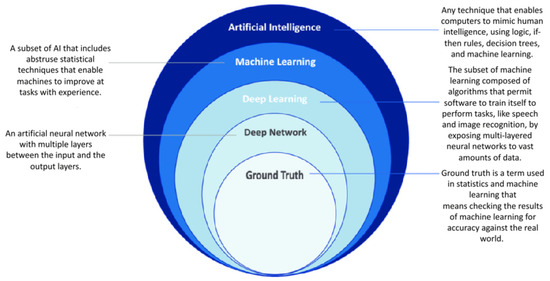

If we consider “human-centered AI”, it is a type of AI that continuously aims to enhance human abilities, address societal needs, and draw inspiration from human behavior and thinking. Figure 1 presents various attempts to define AI across multiple dimensions.

Figure 1.

Definitions of AI in four dimensions (Guan & Ren, 2021; Bellman, 1985; Kurzweil, 1985; Winston, 1992; Nilsson, 1998).

Performing tasks of this nature (which would require human intelligence) is based on learning, reasoning, problem-solving, understanding natural language, and pattern recognition (Vrabie, 2024; Sfetcu, 2024; Popenici, 2023).

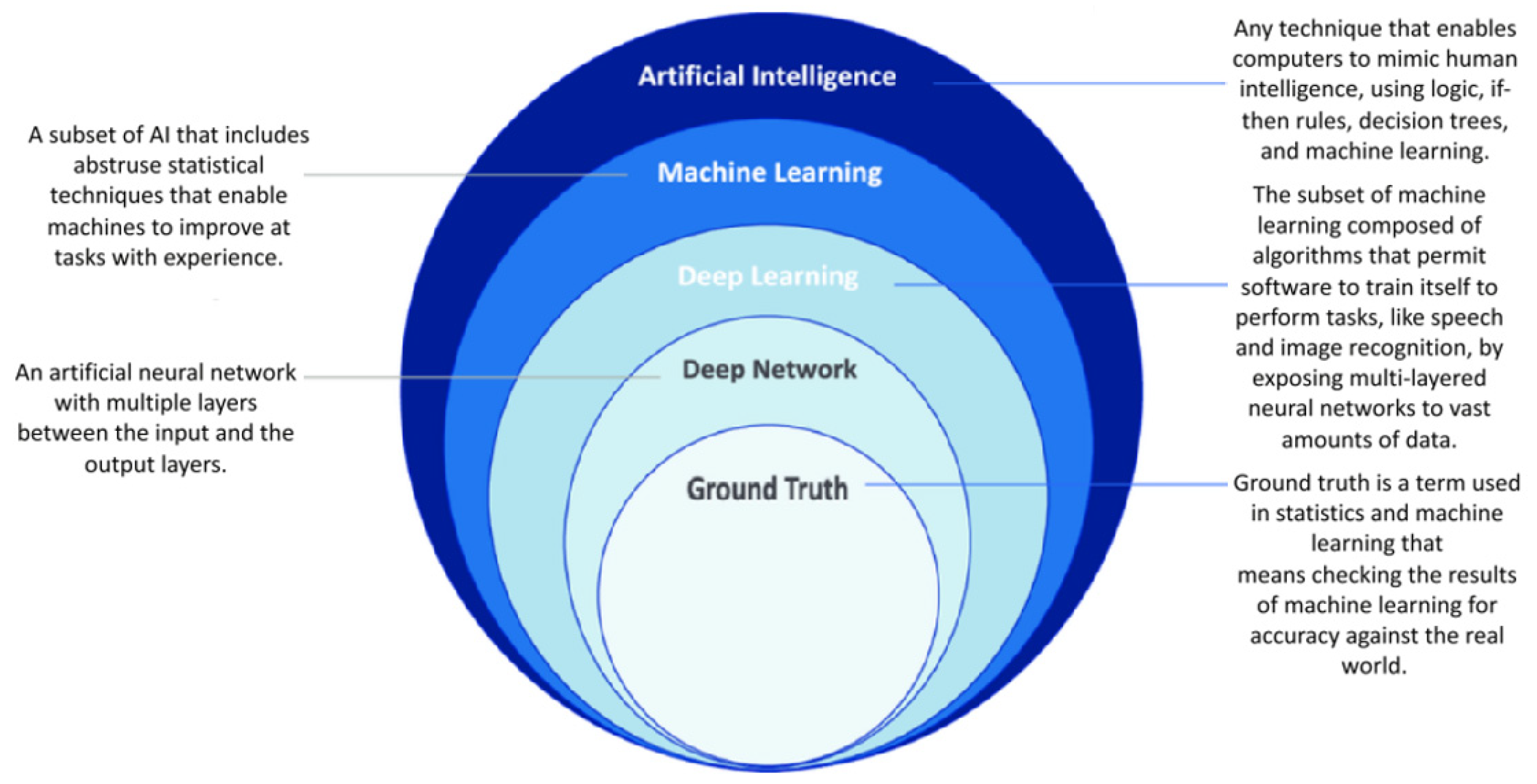

Starting from the basic concepts of AI (Figure 2), it is important to mention that the specialized literature treats “machine learning” distinctly, as a branch of AI that allows machines to learn from data without being explicitly programmed. Machine learning algorithms improve their performance based on experience. Additionally, “deep learning” is recognized as a subset of machine learning, using deep neural networks to analyze and learn from large amounts of data (Kelleher, 2019). The latter is used, for example, in image recognition, natural language processing, etc.

Figure 2.

Basic concepts in AI (Maida et al., 2023).

For deep learning, neural networks (Dumitrescu, 1996) are of particular importance. These models, inspired by the structure and functioning of the human brain, are used to recognize patterns and make predictions. Clearly, the ability for machines to understand, interpret, and generate human language relies on natural language processing, which involves various techniques and algorithms (notable examples include machine translation, chatbots, virtual assistants, and sentiment analysis).

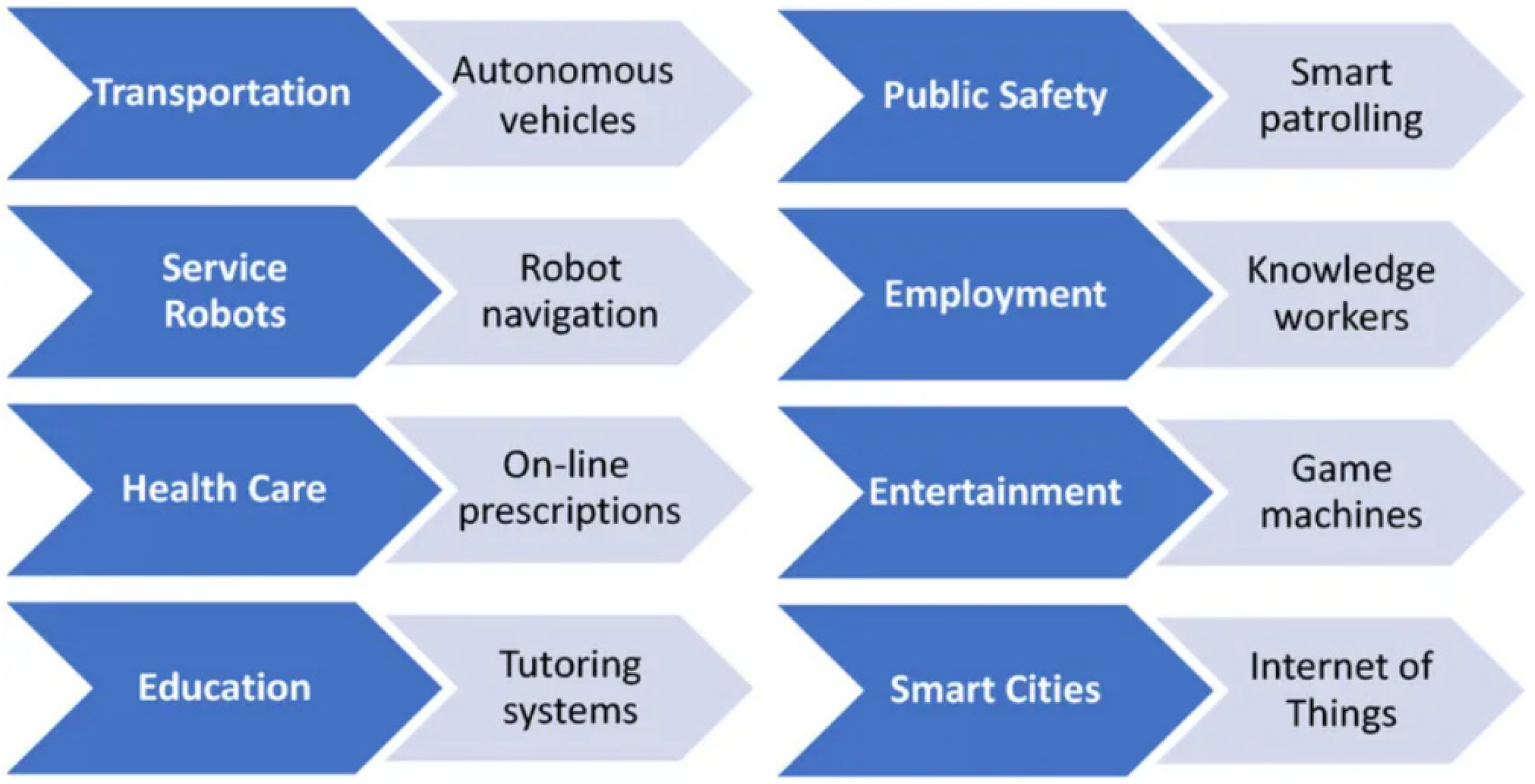

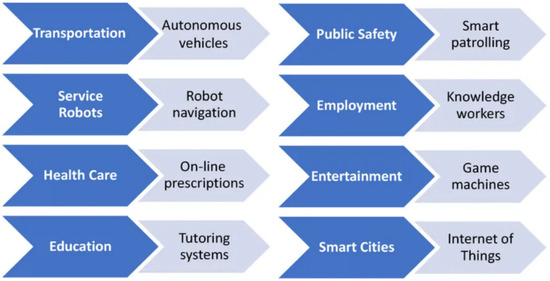

In the context of significant advancements in information and communication technology (ICT) (Lavric et al., 2022; Avătămănitei et al., 2021), AI applications are found across a wide range of fields. Here are just a few examples: medicine—diagnosis, personalized treatments, and medical image analysis; automotives—autonomous vehicles; finance—fraud detection, market analysis, and algorithmic trading; and customer service—chatbots, virtual assistants, etc. (Burgess & WIRED, 2021; Lee et al., 2023; Davenport & Mittal, 2023; Teoh & Goh, 2023; Chaubard, 2023; Lidströmer & Ashrafian, 2021; Martínez, 2021; Attias, 2017).

Figure 3 illustrates this well.

Figure 3.

Fields where AI is used (Constantin, 2022).

Currently, beyond the issues of transparency and interpretability (ensuring that AI decisions are understood and can be explained), there are several technical challenges associated with AI (Krishna, 2024; Mohammad & Chirchir, 2024; Ajami & Karimi, 2023; Oldfield, 2023; Russell & Norvig, 2009). Among these are training algorithms, which require large amounts of data and computational resources, as well as the problem of generalization, which depends on AI’s ability to apply knowledge in new and varied contexts.

In our opinion, the development of strong AI and Superintelligent AI remains a subject of intense debate and research, with potential major impacts on society. On the other hand, it must be considered that there are also some limitations (Lu et al., 2024; Abhivardhan, 2024; Wilks, 2023; Lindgren, 2023; Microsoft.com, 2023; Coeckelbergh, 2020).

Moreover, the motivation for developing this work is also related to aspects concerning ethics, responsibility, and regulation. These aspects are important because they relate to (i) data privacy (protecting personal data used for training algorithms); (ii) safety and security (ensuring that AI systems are safe and do not cause harm); (iii) impact on employment (managing the transition and impact on the labor market due to automation); and (iv) decision-making responsibility (determining accountability for errors or harm caused by AI).

In recent years, several authors have addressed AI issues from the perspective of legal principles and norms. For example, Swan (2024) clarifies the controversial issues surrounding AI use and explores in detail how the creation, distribution, and functioning of AI systems are currently (and will remain for a long time) subject to a broad array of existing laws and regulations worldwide. This author highlights how AI systems are clearly involved in numerous legal regimes, including: “(i) relevant provisions of international law and EU law; (ii) applicable provisions from the laws of the United States, United Kingdom, France, China, India, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore; (iii) national provisions in areas such as health and safety, intellectual property, competition, privacy and data protection, and military engagement”. Furthermore, considering “the lack of international consensus on this important issue, the author suggests that any global agreement on legal responsibilities related to AI use will need to be carefully defined, and provisions will need to be revised to determine how they will apply to any new range of artificial intelligent creations”.

Marwala and Mpedi (2024) show that “AI is rapidly transforming the world, including the legal system. Legal applications in areas such as ethics, human rights, climate change, labor law, health, social protection, inequality, lethal autonomous weapons, criminal justice, autonomous vehicles, contract drafting, legal investigation, criminal analysis, and evidence investigation utilize AI”. Thus, as AI becomes more sophisticated, its impact on the law will increase. These authors provide a starting point for educating lawyers and other legal professionals—and policymakers—about the potential impact of AI on the law, as well as some answers to emerging legal and ethical questions related to AI.

Equally important is another work (Custers & Villaronga, 2022) that provides a comprehensive overview of what is currently happening in the field of law and AI. This includes deepfakes and misinformation, lethal robots, surgical robots, and AI legislation. Here, various contributors to this volume discuss how AI might and should be regulated in public law areas, including constitutional law, human rights law, criminal law, and tax law, as well as private law areas, including liability law, competition law, and consumer law. The author’s contribution covers how AI is changing these areas of law as well as legal practice itself, proving useful for specialists in fields such as law, ethics, sociology, politics, and public administration.

The Romanian scientific literature, in turn, amidst the development of Internet Law (Lazar & Costescu, 2024; Cimpoeru, 2013; Tudorache, 2013; Zainea & Simion, 2009; Garaiman, 2003; Vasiu & Vasiu, 1997), includes a series of works in the same field (Duțu, 2024; Predescu & Predescu, 2023; Banu, 2022; Ciutacu, 2022; Stanila, 2020).

In essence, all of the authors we referred to have demonstrated the necessity and importance of a legal framework addressing AI issues, in the context of preventing any negative future consequences.

3. Institutional Concerns in the EU Regarding AI Issues

3.1. Guidelines and Steps Taken Towards Maximizing the Opportunities Offered by AI

AI is an important component of the European Union’s strategy for developing the digital single market (EC, 2015). In addressing the European Union’s institutional concerns regarding AI-related issues (aiming to provide the most appropriate answer to Question Q1), we first highlight that this type of technology holds a top priority on the European agenda due to its vast potential to transform citizens’ lives—from improving public services to increasing economic efficiency and protecting the environment.

Although the EU lags behind the United States and China in terms of data utilization and massive investments in this field, the EU still has a set of advantages. These include a top-tier academic community in AI research, innovative entrepreneurs, technology-based startups, and a strong industry in strategic sectors such as healthcare, transportation, and space technologies, all of which are very important for AI utilization.

To maintain its global competitiveness, the EU needs to rapidly adopt AI across all sectors of the economy, including SMEs (EC, 2024c). This requires increased investment and easy access to modern AI solutions. At the same time, a well-designed regulatory framework is important to ensure responsible and ethical AI use, protecting citizens’ rights and avoiding associated risks.

European decision-makers have already emphasized the importance of widespread AI implementation, recognizing the major benefits it can bring—from improving healthcare and creating more environmentally friendly transportation solutions to more efficient industrial processes and access to sustainable, low-cost energy. The European Commission’s coordinated plans from 2018 and 2021 aim to position the EU as a global leader in safe and socially beneficial AI (EC, 2024f). This strategy relies on strengthening cooperation between member states, increasing investments, and promoting excellence in research.

However, AI also comes with significant challenges. In addition to risks related to safety and potential disruptive economic and social impacts, the technology requires the rapid adaptation of economies and the workforce. Despite these challenges, the EU remains firmly committed to becoming a global hub for AI development and implementation, where technology evolves from laboratory innovation into practical solutions designed to bring tangible benefits to people and society (ECA, 2024).

The main steps taken by the EU—from initial ideas (Expert Group Debates) to the adoption of the AI Act—are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Steps taken by the EU—from initial ideas (Expert Group Debates) to the adoption of the AI Act (2018–2024).

In recent years, the EU has focused on developing an ecosystem of excellence and trust in the field of AI. These efforts have materialized through two strategic plans that have set out action directions for the Commission and member states, aiming to increase investments and adjust the regulatory framework to support innovation. In addition to these measures, particular emphasis has been placed on mobilizing significant financial resources, both public and private, to stimulate progress in this important field.

The EU has set ambitious investment goals, planning to allocate a total of EUR 20 billion from 2018 to 2020 and to maintain the same level of annual funding over the next ten years. This massive capital mobilization is important for keeping the EU competitive on the global stage, where other major powers are aggressively investing in AI. Additionally, the European Commission (EC) has committed to increasing funding dedicated to research and innovation, allocating EUR 1.5 billion between 2018 and 2020 and aiming to reach EUR one billion annually for the period 2021–2027.

These investments not only reflect the EU’s commitment to advancing in the field of AI but also the need to build a solid research and development foundation that allows for the large-scale implementation of technology for the benefit of citizens and the economy. The AI ecosystem that the EU aims to create is based not only on technological innovation but also on trust, ensuring that AI develops in a responsible, ethical manner, and is oriented towards the common good.

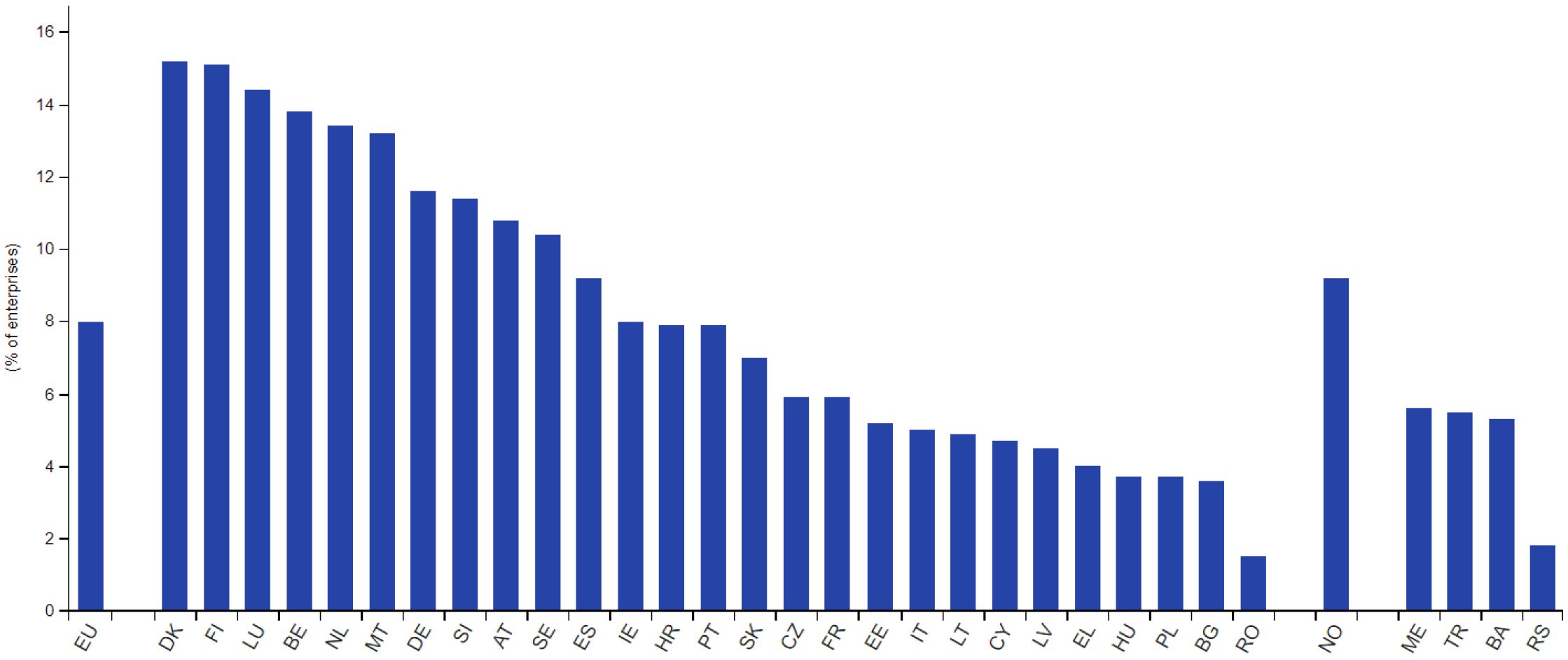

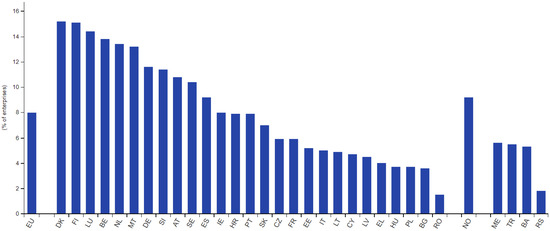

In 2023, 8% of EU enterprises used AI technologies, with 30.4% of large EU enterprises utilizing AI technologies (Figure 4); during the same year, AI was most commonly used by enterprises in the information and communication sector.

Figure 4.

EU enterprises using AI technologies (Eurostat, 2024). Note: break in the time series for France and Sweden.

Clearly, the data reflected in the above graph could see major improvements through the adoption and implementation of appropriate strategies and standards that take into account the various characteristics of the global competitive environment.

3.2. Strategic and Normative Benchmarks for Implementing AI in the EU

3.2.1. Some Features of the AI Strategic Framework in the EU

In 2018, the EC launched the European AI Strategy, focusing on integrating AI across the entire economy, both public and private. Building on this, we will also substantiate the answer to Question Q2 (“What are the strategic and regulatory benchmarks for AI implementation in the EU?”), after which we will add certain analytical approaches. The goal of this strategy is to prepare European society for the changes brought by AI, while ensuring that the development of this technology adheres to a solid ethical and legal framework, in line with the values of the EU. The strategy aims for AI to become a driver of progress, contributing to addressing global challenges such as (EC, 2018e) combating climate change, managing natural disasters, improving transportation safety, and enhancing cybersecurity.

The EU’s approach to AI places people at the center of technology development, with the objective of maximizing the positive impact of AI on citizens’ lives. The strategy is based on three main pillars (EC, 2018e): boosting investments in AI, preparing for the socioeconomic changes brought by technology, and creating a robust ethical and legal framework. These directions are intended to strengthen Europe’s position as a leader in the development of ethical and secure AI.

To ensure the successful implementation of AI, coordination between the EC and member states is very important. This collaboration has led to the development of a coordinated plan aimed at maximizing the impact of investments and encouraging synergies between member states and industry. In this context, member states are required to develop their own national AI strategies aligned with European objectives.

The coordinated plan includes a series of concrete measures, such as (EC, 2018e) promoting investments in secure and ethical AI technologies, fostering collaboration between industry and academia for research and development, adapting educational programs to prepare future generations for an AI-dominated world, and creating important infrastructures such as data spaces and advanced testing centers. Additionally, public administrations are encouraged to adopt AI to become pioneers in technology use.

Moreover, the EU places a strong emphasis on developing clear ethical guidelines for AI use, ensuring the respect for fundamental rights and setting global standards for trustworthy AI. Another priority is updating the European legal framework to address the new challenges brought by AI.

Massive investments are important for the success of the strategy. The EU has set an ambitious goal of reaching annual investments of EUR 20 billion in AI over the next decade (EC, 2018e); between 2018 and 2020, the Commission allocated EUR 1.5 billion for AI research and innovation from the Horizon 2020 program, representing a 70% increase compared to the previous period. Going forward, for the period 2021–2027, the EU aims to invest at least EUR 1 billion annually in AI through the Horizon Europe and Digital Europe programs, thus aligning Europe with global investment levels and preparing for a profound digital transformation.

3.2.2. Developments Following the Launch of the Strategic AI Framework in the EU

In June 2023, the EP adopted its official stance on the EC’s “AI Act” package, the first global set of rules designed to manage the risks associated with AI. This legislative framework aims to protect citizens and ensure a trustworthy environment for AI use, allowing the EU to become a global leader in the data-driven economy and AI applications. A high-quality digital infrastructure, combined with regulations that protect fundamental rights, provides an optimal framework for the safe development and use of this technology.

Wishing to highlight possible developments following the launch of the AI strategic framework implementation in the EU (as an answer to Question Q2), we point out that a report prepared by the European Parliament’s Think Tank estimates that the implementation of AI technology could increase labor productivity by between 11% and 37% by 2035. Additionally, AI could help reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 4%, contributing to the ambitious goals set by the European Green Deal (RG, 2024b).

While the adoption of AI will transform certain jobs, this technology also promises to create new, better-paid employment opportunities. Education and continuous training will play an important role in preventing long-term unemployment and preparing the workforce for new technological requirements. According to OECD objectives, it is estimated that 14% of jobs in member countries will be automated, while 32% will undergo major transformations but will not disappear.

AI’s contribution to economic growth is vast and manifests through multiple mechanisms:

- Increasing productivity by creating a virtual workforce;

- Automating complex processes that can solve problems and improve autonomously;

- Driving innovation, which generates new economic sectors and sources of revenue.

Investments in AI play an important role in realizing these economic benefits. In 2019, the EU invested between EUR 7.9 and 9 billion in AI, 39% more than in 2018, a growth rate that, if maintained, could exceed the annual target of EUR 20 billion before the 2030 deadline (RG, 2024b). According to an AI Watch report, investments by member states have increased significantly, with countries like Ireland, Belgium, and Austria investing over EUR 50 million in 2019 and experiencing notable economic growth (Watch.ec, 2024).

On the other hand, countries like Bulgaria, Slovenia, and Croatia, although having lower investment levels, achieved the highest annual growth rates, reaching 96%, 75%, and 67%, respectively. France and Germany lead the investment rankings in AI, with 22% and 18% of the European total, and together with Spain, these three countries accounted for 53% of total EU investments in AI.

The increase in investments has been largely supported by the private sector, which contributed two-thirds of the total funds, while the public sector saw a one-third increase in investments within a single year, demonstrating a strong commitment from all economic actors to the development of AI in Europe.

3.2.3. Development and Adoption of the EU AI Act

After a lengthy negotiation process, the EC, the Council, the Parliament, and the EU member states reached a final agreement at the beginning of 2024. The AI Act, which came into effect on 1 August 2024, was created to ensure that AI technology developed and used in the EU is safe and trustworthy, providing robust protection measures for citizens’ fundamental rights. The aim of this regulation is to harmonize the internal market for AI across the EU, promoting widespread adoption of this innovative technology while creating an environment that encourages investment and innovation (EC, 2024g).

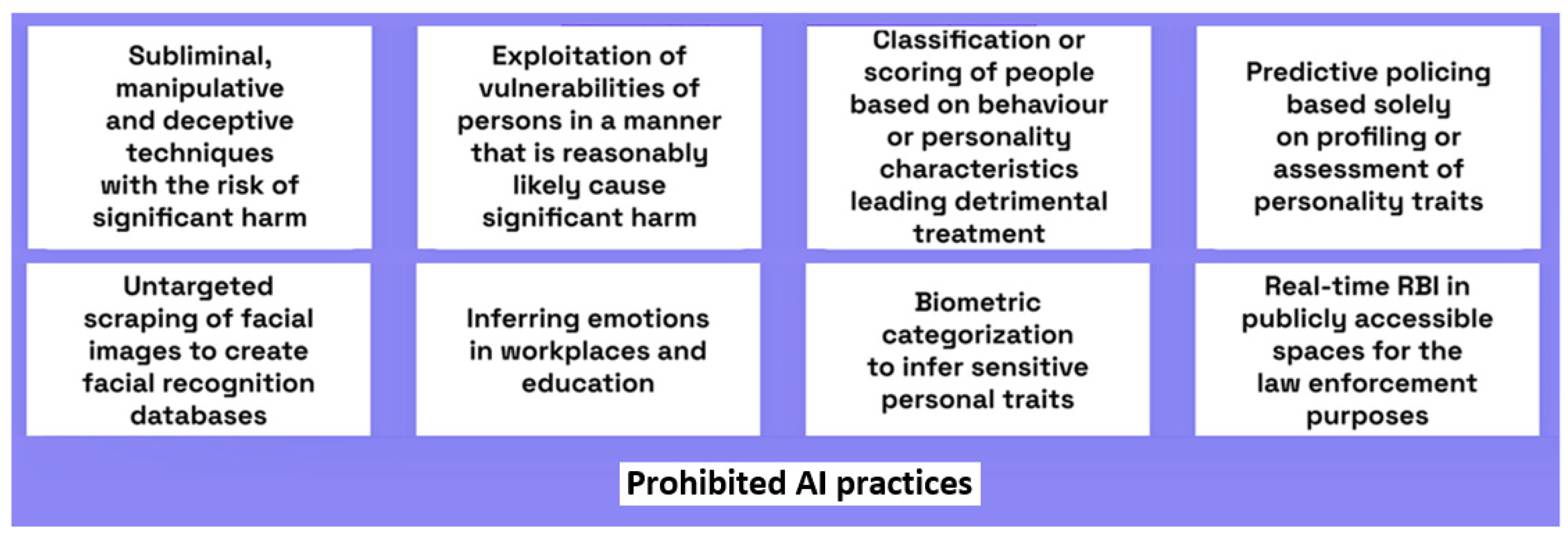

The AI Act introduces a regulatory framework based on four risk levels: minimal risk, high risk, and unacceptable risk (Figure 5). Each of these levels has distinct requirements and regulations designed to ensure the responsible use of AI. Additionally, the regulation includes specific rules for general-purpose AI (GPAI) models to ensure these systems comply with European safety and ethical standards.

Figure 5.

The four risk classes of the EU AI Act (Trail-ml.com, 2024).

Most provisions of the AI Regulation will come into effect on 2 August 2026. However, prohibitions concerning AI systems that present an unacceptable risk will be enforced six months after the regulation’s entry into force, while regulations for GPAI models will apply after 12 months (EP, 2024).

As a regulation, the EU AI Act is directly applicable in all member states starting 1 August 2024. However, a transition period has been provided, allowing developers and companies in the EU time to comply with the new rules. Regulations concerning the use of AI will be enforced from 2 February 2025, while rules for GPAI models will become mandatory from 1 May 2025.

The new rules impose clear obligations on AI providers and users, depending on the level of risk their systems present (EC, 2024g). The AI Act, structured into 13 chapters (Euaiact.com, 2024), covers important aspects such as prohibitions on dangerous AI practices, high-risk AI systems, transparency obligations for developers and users, GPAI models, measures for innovation, governance, and post-market monitoring. Additionally, systems that violate human rights or undermine the rule of law, such as those manipulating individual behavior or exploiting social vulnerabilities, are completely prohibited.

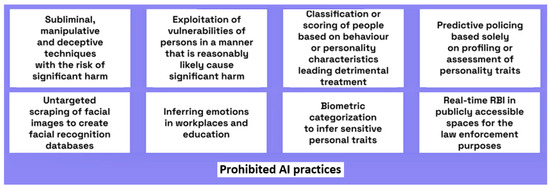

One of the most important articles in the AI Act is Article 5, which lists prohibited AI practices and identifies AI systems with unacceptable risk. This article will be the first to come into force under the regulation’s progressive implementation, which will occur over a period of 24 months from its entry into force (Güçlütürk & Vural, 2024).

In total, eight key AI practices are prohibited within the EU under this regulation (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Prohibited AI practices in the EU under the EU AI Act (Güçlütürk & Vural, 2024).

The new regulation not only imposes strict rules but also offers benefits for start-ups and SMEs, allowing them to develop and test AI models before bringing them to market. An important aspect is the approach to GPAI models, which do not present significant systemic risks and, therefore, will be subject to simpler regulations, primarily focused on transparency.

The regulation is extensive and complex, covering the entire value chain of the AI industry, from developers to end-users. Starting from February 2025, companies in the EU will need to comply with the new rules, especially those using high-risk AI applications in sectors such as energy, healthcare, financial services, and telecommunications (Issuemonitoring.eu, 2024).

Failure to comply with these regulations will result in a ban on using AI technology for those who do not adhere. To ensure proper enforcement of the regulation, both AI developers and users will be required to implement robust governance mechanisms, ensuring compliance with the new EU requirements.

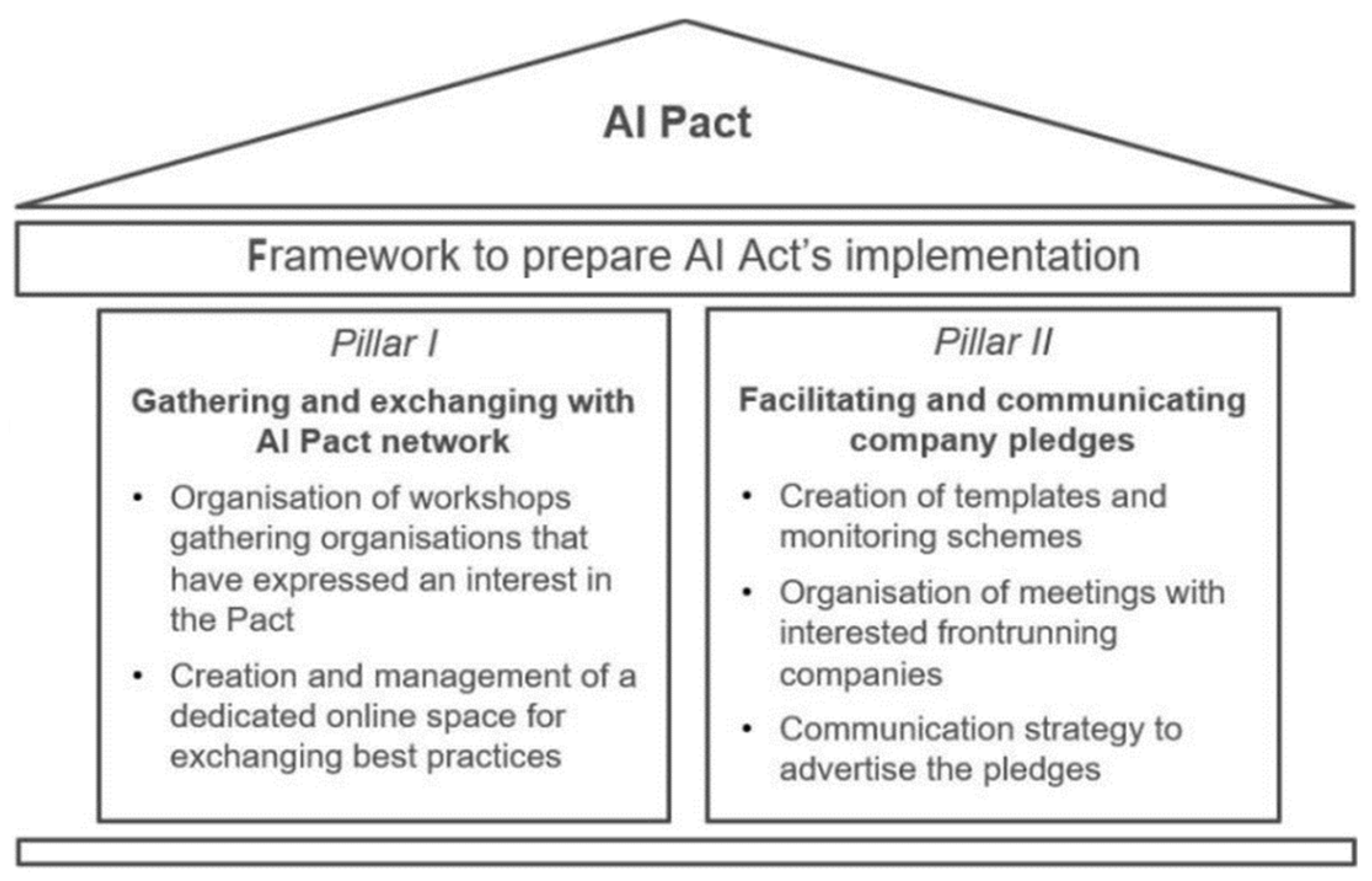

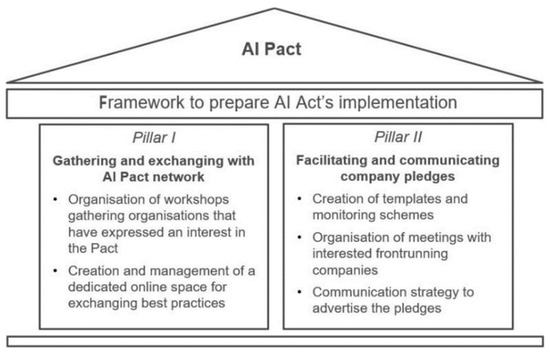

3.2.4. AI Pact

To facilitate the transition to full implementation of the AI Regulation, the EC launched the AI Pact in November 2023 (EC, 2024b). This initiative aims to encourage AI developers to voluntarily adopt the key provisions of the regulation ahead of the legal deadline.

By 2 August 2025, EU member states will need to designate national authorities responsible for overseeing compliance with AI rules and monitoring the market. The Commission’s AI Office will play a central role, supervising the application of the regulation at the European level and ensuring adherence to the rules concerning GPAI models (EC, 2024g).

The AI Pact, created by the AI Office, is based on two important pillars (RG, 2024a). The first pillar provides a central point of connection among Pact network members, facilitating the exchange of best practices and offering useful guidance for implementing the AI Act. The second pillar encourages providers and operators of AI systems to prepare in advance and begin applying the requirements and obligations outlined in the regulation, ensuring a smooth transition to the new standards (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

AI Pact—two-pillar approach (EC, 2024g).

The AI Pact offers numerous advantages to its network members, which includes over 550 organizations from various fields and countries. The Pact provides participants with the opportunity to test their innovative solutions and share results with the entire community, while also benefiting from support from the EC.

This support takes several forms, including fostering a common understanding of the AI Pact’s objectives. Participants are assisted in adopting appropriate measures to prepare for the implementation of the regulation, such as developing internal processes, training staff, and evaluating AI systems. Additionally, the Pact facilitates knowledge exchange among network members and helps increase the visibility and credibility of AI solutions, emphasizing the commitment to ethical and trustworthy AI.

A significant outcome of these initiatives is the substantial increase in trust in AI technologies, both within the participating community and among the general public.

4. Preparations of a Strategic and Normative Nature at the Level of the Romanian State for AI Era

The approaches in this part of our analysis focus on the preparations of a strategic and normative nature at the national level for the AI Era, including legislative attempts to prevent the deepfake phenomenon, in the context of the drafting and adoption of the EU AI Act and AI Pact. In fact, this is precisely where, closely aligned with European regulations, the answer to Question Q4 is thoroughly addressed.

Romania has begun to shape its own guidelines on artificial intelligence in the context of European efforts to regulate this emerging technology. The process of drafting these guidelines has been influenced by the need to align with the AI Act, which aims to ensure the safe, ethical, and responsible use of artificial intelligence in the member states of the EU.

After the COVID-19 pandemic period, Romanian authorities initiated discussions on adopting an NAIS. The drafted document seeks to define strategic directions for the development and implementation of artificial intelligence at the national level. In this process, an important objective is the establishment of ethical and transparency principles in the use of artificial intelligence, in line with European standards. Additionally, efforts have been made to identify priority areas for AI application, such as public administration, healthcare, cybersecurity, and the digital economy. At the same time, authorities have considered creating a legal framework to support innovation and research in this field.

Another important aspect has been aligning with European Union regulations on the classification and governance of risks associated with artificial intelligence, according to the categories defined in the AI Act, ranging from unacceptable risk to minimal risk. As the regulatory project was debated and finalized at the European level, Romania’s connection with the EU AI Act became increasingly stronger.

4.1. Romania’s Adoption of the NAIS

In the current context of technological development, where AI is becoming an important element and transforming nearly all areas of life, the Romanian Government (RG) has responded to the new European regulation by adopting the NAIS for the period 2024–2027. Published on 11 July 2024, and applicable from a later date, this strategy does not impose detailed rules on AI usage but establishes guidelines based on proposals from the National AI Committee and suggestions from the private sector.

The primary goal of this strategy is to support public administration in standardizing and regulating AI development, preparing Romanian society to understand, accept, and leverage the transformative impact of this technology. Additionally, the NAIS aims to strengthen education and skills in research, development, and innovation (RDI) related to AI, promoting the use of specific infrastructure and datasets. Strategic partnerships will facilitate technological transfer and the adoption of new technologies throughout society.

To ensure the effective coordination of the NAIS implementation, an Interministerial Committee has been established, consisting of representatives from 34 relevant institutions. This committee will develop a robust governance and regulatory system for AI, responsible for monitoring and adjusting the implementation process. The Ministry of Digitalization (MCID) and the Authority for Digitalization of Romania (ADR) will initiate a detailed implementation plan, with specific responsibilities, deadlines, and resources required for each involved institution.

In alignment with the EU’s goals to become a global leader in AI, Romania must adapt to these trends by creating a regulatory framework suited to the national context and leveraging expertise in science, technological innovation, investment, and collaboration between academia, the private sector, research, and public administration.

Thus, the NAIS builds on strategic actions at the European level but is tailored to the Romanian context, focusing on key areas such as research, development, innovation, economic competitiveness, education, and digitalization. The strategy defines six general objectives aligned with priority axes from EU strategic documents and details 13 specific objectives (Table 2), providing a comprehensive and clear implementation plan.

Table 2.

General and specific objectives of the NAIS (RG, 2024a).

It is important to emphasize that the NAIS has the potential to position Romania as a regional leader in the technology field, significantly contributing to the development of national capacities and the country’s efficient transition to a knowledge-based society and economy.

Regarding the expected impact of the strategy’s implementation, the benefits will be reflected in several key areas (RG, 2024a):

- Progress in research and innovation in ICT: this will include the development of human resources, increased expertise, and recognition both nationally and internationally.

- Improvement of AI education and training: the strategy will support the development and preparation of AI specialists through the educational system, ensuring a solid skill base in the field.

- Dissemination of AI knowledge and skills: it will promote the spread of these among the population and the business sector, facilitating the integration of AI across various domains.

- Development of AI infrastructure: investments will be made in specific infrastructures, regulations, and datasets, which are important for technological advancement.

- Strengthening the institutional AI ecosystem: the strategy will promote the development of research centers, specialized companies, and spaces for testing and experimenting with AI solutions.

Additionally, the strategy will positively influence the adoption of AI solutions in the public sector, improving digital services, and in the private sector, contributing to increased economic competitiveness. Moreover, it will strengthen AI governance and regulation and support the integration of AI technologies across all sectors of the national economy.

4.2. Enhancing/Improving the National Regulatory Framework

4.2.1. Drafting an AI Law—The Coordinates for Regulation, Implementation, Use, Development, and Protection of AI in Various Environments

Romanian lawmakers, in drafting legislation dedicated to AI, acknowledge that the technological advancements and innovations of recent decades have had a profound impact on all aspects of human life (RP, 2024a). Like other EU member states, Romania is in a continuous process of adapting to the AI Era, with the use of this technology increasing both in the private and public sectors. Currently, AI is being applied in areas such as cybersecurity, data analysis, process automation in public administration, and the optimization of financial and healthcare services. ICT sector companies are the main actors in AI adoption, while academic and research initiatives have started to play an important role in developing advanced solutions.

The challenges that exist are linked to the fact that for a period of time, strategic guidelines were not adopted in this regard—the Romanian Government becoming more involved only after the pandemic stage (COVID-19). The digital infrastructure is underdeveloped, and there is also a shortage of specialists in this field. Additionally, there are concerns regarding the impact of AI on the labor market, personal data protection, and the use of deepfakes for disinformation purposes.

A legislative bill aims to establish a comprehensive framework for the implementation, use, development, and protection of AI in Romania, taking into account recent technological advancements and the necessary measures to secure cyberspace at both the national and European levels. This law seeks to regulate AI across various fields such as the economy, society, technology, medicine, culture, and national security, without affecting the values and norms established by civil law (RP, 2024b).

According to the text approved by the Romanian Senate, AI is defined as an advanced technology that processes large amounts of data, metadata, and information using specific algorithms to execute tasks within an optimal timeframe. The law also introduces key terms such as (i) physical environment—the characteristics of the surrounding environment, including dimensions, surface area, and obstacles; and (ii) virtual environment—the characteristics of a non-physical environment where data are stored and accessible via electronic devices or quantum computers.

The law classifies AI into three categories based on the complexity of its functionality: (i) Narrow AI, which performs a limited set of activities; (ii) General AI, capable of executing tasks similar to those performed by humans; and (iii) Super AI, which surpasses human intelligence. The classification is based on required resources such as human resources, data, technology, and the level of expertise.

AI will be implemented across multiple domains without specific limitations, including economic, social, technological, educational, medical, and military sectors. Its use will be supported by both traditional computing equipment and quantum technology, and its development will involve research and collaboration at the national and international levels. AI protection will encompass physical security measures and legal regulations, prohibiting its use for human resource automation within organizations and biometric data use, except for purposes related to crime prevention and investigation.

Institutions such as the National Cyberint Center, the Special Telecommunications Service, the National Cybersecurity Directorate, and the National Institute for Research and Development in Informatics will be responsible for monitoring and controlling the flow of data and information used in AI, as well as its impact on users and the public. Additionally, violations of the legislation will be considered offenses under special laws or the Penal Code, depending on the severity of the offense and where it was committed.

4.2.2. Legislative Attempts to Prevent the Deepfake Phenomenon

In the context of implementing and utilizing AI, deepfake refers to an advanced digital content manipulation technique that uses machine learning and image generation technologies to produce fake but realistic and convincing audio, video, or photo materials (Bradu & Cădariu, 2024). The term “deepfake“ combines the concepts of “deep learning” and “fake”, highlighting the complexity and sophistication of this technology.

The authors of the referenced study emphasize that multiple techniques are used to create deepfakes, including image generation through generative adversarial networks (GANs). These involve a system consisting of two neural networks with opposing goals: one focuses on generating fake content, while the other aims to detect these falsifications. Through an iterative process, these networks continuously learn and improve, optimizing the quality and credibility of the fakes through adjustments based on positive and negative feedback.

Although the impact of deepfakes in Romania has not yet reached the alarming level observed in other countries, the associated risks are increasing. Their use for disinformation, political manipulation, and digital fraud poses serious threats to information security and public trust in media content. Especially in the context of elections and the rapid spread of information on social media platforms, deepfakes can contribute to the amplification of fake news and influence public perception of events or individuals.

The adoption of specific measures to combat deepfakes in Romania is still in its early stages. Although there are government-level initiatives regarding cybersecurity and the fight against disinformation, the implementation of concrete solutions for detecting and regulating deepfakes remains an ongoing process.

The Need for Responsible Use of Technology in the Context of the Deepfake Phenomenon

In the context of national regulations, a recent legislative proposal has been initiated to address the responsible use of technology in relation to the deepfake phenomenon (RP, 2023a). The Romanian legislator, in the explanatory memorandum, highlights the rapid development of technology, including AI and artificial virtual reality techniques, as well as significant advances in machine learning. It emphasizes the urgent need to intervene in order to mitigate the harmful effects of false content generated by these technologies.

The legislator points out that deepfake represents a much more serious threat than traditional fake news, due to its ability to integrate text, photos, video, and audio into a single media product. Deepfake images and recordings (Severe Fakes) can cause significant harm not only to individuals’ reputations and dignity but also to public and private organizations or even state institutions. The creation and dissemination of such content can affect social, political, and national security interests, eroding trust in state institutions and causing considerable reputational damage.

While deepfakes may seem harmless, they have the potential to cause long-term negative effects. Deepfake technology has evolved to become increasingly convincing and accessible to the public, with the capacity to disrupt the media and entertainment industries and, more recently, contribute to significant financial fraud. According to the cited source, the United States and some European countries have adopted various legislative measures to limit this phenomenon (RP, 2023b).

The Prefiguration of a Special Norm

Currently, Romanian legislation does not specifically regulate the creation and dissemination of images, audio, or video recordings generated through AI or augmented reality techniques, whether for malicious purposes or in artistic and advertising contexts. Therefore, the Romanian legislator has deemed it important to create a legal framework that addresses these issues.

The recently proposed—as a special legal norm—bill aims to establish clear rules for the use of these technologies, allowing for the creation and notification of materials only when they are produced for legitimate, commercial, and clearly identified purposes. In the absence of such notifications, materials created and disseminated for malicious purposes will be prohibited. The law defines deepfakes as “video or audio content created and managed with the help of AI to make it appear as if a person has said or done things they did not actually say or do” (RP, 2023a). It is important that the creation and distribution of deepfake materials be carried out with discernment and clear intent, and such actions will be considered offenses under this legislative proposal.

Specifically, the law prohibits the dissemination of any visual or audio content generated or manipulated through deepfake technology if it is not accompanied by a clear warning. The warning must be visible on at least 10% of the visual material or present at the beginning and end of the audio content, in the form of the message: “This material contains imaginary scenarios.” (RP, 2023b).

Violations of these regulations, if they do not constitute offenses under criminal law, will be considered administrative infractions and will be fined between RON 10,000 and RON 100,000. In cases of repeated violations, the penalty may reach RON 200,000. Infractions will be detected either upon complaint by affected individuals or ex officio by representatives of the National Audiovisual Council, who can order the cessation of the dissemination of unaccompanied deepfake materials and require their removal.

5. Conclusions

The Era of AI offers remarkable opportunities for advancement but also presents major challenges that require careful management and long-term vision. The EU has a solid scientific and industrial foundation for AI development, with a well-established legislative framework that protects consumers and encourages innovation while advancing the creation of a single digital market. All of these elements place the EU in a favorable position to become a leader in the AI revolution, in alignment with its fundamental values.

The approach to AI presented in our paper emphasizes the need for close collaboration at the European level to ensure that all European citizens benefit from digital transformation, that the necessary resources are allocated for AI development, and that the Union’s fundamental values and rights are prioritized in this context.

This paper details the impact and significance of AI on the economy and society, focusing on the strategic and normative approaches of the EU and Romania toward this technology. The author sought to provide convincing answers to a series of essential questions (Q1–Q4) regarding the issue of artificial intelligence in both the European and national (Romanian) contexts. To this end, he analyzed the institutional concerns of the European Union related to AI, highlighted the strategic and normative benchmarks for the implementation of this technology, and integrated relevant analytical perspectives. Furthermore, he aimed to capture the developments that followed the initiation of the process to implement the European strategic framework for AI.

Simultaneously, the context in which key documents such as the EU AI Act and AI Pact were developed and adopted was examined, emphasizing both the strategic and normative efforts undertaken at the national level in Romania to prepare for the AI Era, as well as the legislative initiatives aimed at preventing the deepfake phenomenon.

Based on the conclusions of this paper, we believe that adopting clear strategic directions for the upcoming period is necessary. First, we recommend strengthening the national and European legislative framework regarding artificial intelligence and combating the deepfake phenomenon by continuously updating regulations in line with technological and social developments. Secondly, we emphasize the importance of intensifying digital education and media literacy programs so that citizens are better prepared to recognize and manage the risks associated with manipulated content.

Furthermore, we consider it essential to support cooperation among European Union member states and to develop international partnerships in applied research, particularly for the enhancement of automated deepfake detection technologies and the protection of the information space. Another important aspect is the establishment of effective monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for the impact of adopted legislative and strategic measures, so that rapid adjustments can be made when reality dictates.

Finally, we underline the need to maintain a balance between fostering technological innovation and protecting the fundamental rights and freedoms of citizens, within a solid ethical framework that respects democratic principles.

Future Research Directions

Considering the obtained results, we believe that this study should be continued in several directions, after better problematization of the impact and limitations of the existing regulations, aiming to identify significant improvement directions in the analyzed field. Firstly, it is important to assess the concrete impact of the implementation of the AI Law and the AI Pact on the economies of the member states and the business environment.

Second, future research—conducted within interdisciplinary teams—should focus on a comparative analysis of the national AI strategies adopted by EU member states to identify best practices and potential shortcomings. Additionally, we aim to give our future work a more technical character by involving experts from academia, including computer scientists, statisticians, and hardware engineers.

Undoubtedly, the continuous monitoring of technological and regulatory developments in the field of AI is important to ensure the relevance and effectiveness of policies in the face of rapid changes in this sector.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express their gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their efforts to improve the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADR | Authority for Digitalization of Romania (ADR) |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AI HLEG | High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence |

| ALTAI | Assessment list on trustworthy AI |

| EC | European Commission |

| ECA | European Court of Accounts |

| EP | European Parliament |

| EU | European Union |

| GANs | Generative adversarial networks |

| GO | General objective |

| GPAI | General-purpose AI models |

| ICT | Information and communication technology |

| MCID | Ministry of Digitalization |

| NAIS | National AI Strategy |

| NCD | National Cybersecurity Directorate |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| RDI | Research, development, and innovation |

| RG | Romanian Government |

| RP | Romanian Parliament |

| SMEs | Small- and medium-sized enterprises |

| SO | Specific objective |

| TEF | Testing and Experimentation Facility |

References

- Abhivardhan. (2024). Artificial intelligence ethics and international law (2nd ed.). Practical Approaches to AI Governance. BPB Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ajami, R. A., & Karimi, H. A. (2023). Artificial intelligence: Opportunities and challenges. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business, 24(2), 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attias, D. (2017). The autonomous car, a disruptive business model? In D. Attias (Ed.), The automobile revolution: Towards a new electro-mobility paradigm. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avătămăniței, S., Beguni, C., Căilean, A., Dimian, M., & Popa, V. (2021). Evaluation of misalignment effect in vehicle-to-vehicle visible light communications: Experimental demonstration of a 75 meters link. Sensors, 21, 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banu, M. (2022). Reglementarea sistemelor de inteligență artificială la nivelul Uniunii Europene. Departamentul de Studii Parlamentare și Politici UE. Direcția Pentru Uniunea Europeană. Romanian Parliament, Bucharest. Available online: https://www.cdep.ro/afaceri_europene/afeur/2022/st_3507.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Bellman, R. (1985). Artificial intelligence: Can computers think? Boyd & Fraser Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bradu, R., & Cădariu, N. (2024). AI, deepfake și decredibilizarea unei probe până acum incontestabile. Juridice.ro. Available online: https://www.juridice.ro/731649/ai-deepfake-si-decredibilizarea-unei-probe-pana-acum-incontestabile.html (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Burgess, M., & WIRED. (2021). Artificial intelligence. How machine learning will shape the next decade (WIRED guides). Cornerstone Digital. [Google Scholar]

- Chaubard, F. (2023). AI for retail. A practical guide to modernize your retail business with AI and automation. John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cimpoeru, D. (2013). Dreptul internetului. Publishing House C.H. Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Ciutacu, I. (2022). The effects of the implementation of artificial intelligence in justice on fundamental rights and procedural rights. UNBR—Working Paper WP. Available online: https://www.unbr.ro/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/4_Ciutacu-Ioana_Efectele-implementarii-inteligentei-artificiale-in-justitie.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Coeckelbergh, M. (2020). AI ethics. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Constantin, L. (2022). Ce este inteligența artificială? Cum funcționează, domenii de utilizare, riscuri și viitorul acesteia. Available online: https://techcafe.ro/stiinta/ce-este-inteligenta-artificiala-cum-functioneaza-domenii-de-utilizare-riscuri-si-viitorul-acesteia (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Custers, B., & Villaronga, E. F. (2022). Law and artificial intelligence regulating AI and applying AI in legal practice (B. Custers, Ed.). Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-94-6265-523-2 (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Davenport, T., & Mittal, N. (2023). All-in on AI. How smart companies win big with artificial intelligence. Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu, D. (1996). Inteligenta artificiala. Retele neuronale. Teorie si aplicatii. Teora. [Google Scholar]

- Duțu, M. (2024, April 5). Spre un drept al inteligenței artificiale. Premise, actualități. Perspective. Comunicare Susținută în Cadrul Conferinței Internaționale “Casa Ecologiei”, Bucharest, Romania. Available online: https://www.juridice.ro/essentials/7653/ce-fel-de-reglementare-ce-fel-de-etica-ce-drept-pentru-inteligenta-artificiala (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2015). A digital single market strategy for Europe. Communication from the Commission to the European parliament, the Council, the European economic and social committee and the Committee of the regions {SWD(2015) 100 final}. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0192 (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2018a). Artificial intelligence: Commission kicks off work on marrying cutting-edge technology and ethical standards. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_1381 (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2018b). Artificial intelligence: Commission outlines a European approach to boost investment and set ethical guidelines. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_3362 (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2018c, December 18). Artificial intelligence: Draft Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. Brussels. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/draft-ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2018d). Commission appoints expert group on AI and launches the European AI alliance. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/node/2891/printable/pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2018e). Communication from the Commission to the European parliament, the European council, the Council, the European economic and social committee and the Committee of the regions. Coordinated plan on artificial intelligence, COM(2018) 795 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0795&from=FR (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2018f). Communication from the Commission to the European parliament, the European council, the Council, the European economic and social committee and the Committee of the regions on artificial intelligence for europe. Policy and legislation. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0237 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2018g). Coordinated plan on the development and use of artificial intelligence made in Europe—2018. ANNEX to the Communication from the Commission to the European parliament, the European council, the Council, the European economic and social committee and the Committee of the regions, COM(2018) 795 final. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/european-approach-artificial-intelligence (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2018h). Liability for emerging digital technologies accompanying the document, Communication from the Commission to the European parliament, the European Council, the council, the European economic and social committee and the Committee of the regions. Commission staff working document: Artificial intelligence for Europe {COM(2018) 237 final}. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/european-commission-staff-working-document-liability-emerging-digital-technologies (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2018i). Member states and commission to work together to boost AI “made in Europe”. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_6689 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2018j). Stakeholder consultation on draft ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai/stakeholder-consultation-guidelines-first-draft.html (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2018k). The European AI alliance. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/european-ai-alliance (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2019a). Communication from the Commission to the European parliament, the European Council, the council, the European economic and social committee and the Committee of the regions. Building trust in human-centric artificial intelligence, COM(2019) 168 final. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/communication-building-trust-human-centric-artificial-intelligence (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2019b). Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. High-level expert group on artificial intelligence. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2019c). Pilot the assessment list of the ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai/pilot-assessment-list-ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai.html (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2019d). Policy and investment recommendations for trustworthy AI. High-level expert group on artificial intelligence. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/policy-and-investment-recommendations-trustworthy-artificial-intelligence (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2019e). The first European AI alliance assembly. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/events/first-european-ai-alliance-assembly (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2020a). Artificial intelligence—ethical and legal requirements. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12527-Artificial-intelligence-ethical-and-legal-requirements_en (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2020b). Assessment list for trustworthy AI (ALTAI). High-level expert group on artificial intelligence (AI HLEG) presented their final assessment list for trustworthy AI. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/assessment-list-trustworthy-artificial-intelligence-altai-self-assessment (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2020c). High-level expert group on AI: Sectorial recommendations of trustworthy AI. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/expert-group-ai (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2020d). On artificial intelligence—A European approach to excellence and trust—COM(2020) 65 final. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/d2ec4039-c5be-423a-81ef-b9e44e79825b_en?filename=commission-white-paper-artificial-intelligence-feb2020_en.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2020e). Second European AI alliance assembly. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/events/second-european-ai-alliance-assembly (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2020f). White paper on artificial intelligence—A European approach to excellence and trust. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/node/798/printable/pdf (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2021a). Communication on fostering a European approach to artificial intelligence. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/node/9758/printable/pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2021b). Coordinated plan on artificial intelligence. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/coordinated-plan-artificial-intelligence-2021-review (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2021c). High-level conference on AI: From ambition to action. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/node/10210/printable/pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2021d). Impact assessment of the regulation on artificial intelligence, policy and legislation. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/impact-assessment-regulation-artificial-intelligence (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2021e). Opinion factsheet European approach to artificial intelligence—AI act (opinion number: CDR 2682/2021)—The European committee of the regions CoR). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52021AR2682 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2021f). Opinion of the European central bank of 29 December 2021 on a proposal for a regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (CON/2021/40) (2022/C 115/05), preparatory acts. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52021AB0040 (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2021g). Product liability directive—Adapting liability rules to the digital age, circular economy and global value chains. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12979-Product-Liability-Directive-Adapting-liability-rules-to-the-digital-age-circular-economy-and-global-value-chains_en (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2021h). Proposal for a regulation laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/node/9756/printable/pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2021i). Proposal for a regulation of the European parliament and of the Council laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (AI Act) and amending certain union legislative acts. Available online: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-14278-2021-INIT/en/pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2021j). Proposal for a regulation of the European parliament and of the Council on general product safety, amending Regulation (EU) No. 1025/2012 of the European parliament and of the Council, and repealing Council Directive 87/357/EEC and directive 2001/95/EC of the European parliament and of the council, COM/2021/346 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0346 (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2021k). Regulation on artificial intelligence. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/our-work/opinions-information-reports/opinions/regulation-artificial-intelligence (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2022a). Artificial intelligence act: Council calls for promoting safe AI that respects fundamental rights. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/12/06/artificial-intelligence-act-council-calls-for-promoting-safe-ai-that-respects-fundamental-rights (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2022b). EC. Launch event for the Spanish regulatory sandbox on artificial intelligence. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/node/11008/printable/pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2022c). Liability rules for artificial intelligence. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/business-economy-euro/doing-business-eu/contract-rules/digital-contracts/liability-rules-artificial-intelligence_en (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2023a). Commission welcomes political agreement on artificial intelligence act. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_6473 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2023b). MEPs ready to negotiate first-ever rules for safe and transparent AI. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20230609IPR96212/meps-ready-to-negotiate-first-ever-rules-for-safe-and-transparent-ai (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2024a). AI act. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/node/9745/printable/pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2024b). AI pact. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/ro/policies/ai-pact (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2024c). Benefits of AI. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/excellence-and-trust-artificial-intelligence_ro (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2024d). Commission launches AI innovation package to support Artificial Intelligence startups and SMEs. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/node/12369/printable/pdf (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2024e). European AI office. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/ai-office (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2024f). European approach to artificial intelligence. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/ro/policies/european-approach-artificial-intelligence (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- EC/European Commission. (2024g). European artificial intelligence act comes into force. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_24_4123 (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- ECA/European Court of Accounts. (2024). EU Artificial intelligence ambition. Stronger governance and increased, more focused investment essential going forward. Special report. Available online: https://www.eca.europa.eu/ECAPublications/SR-2024-08/SR-2024-08_RO.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- EP/European Parliament. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024f laying down harmonised rules on AI and amending regulations (EC) No. 300/2008, (EU) No. 167/2013, (EU) No. 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202401689 (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Euaiact.com. (2024). EU AI act. Available online: https://www.euaiact.com/title/13 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Eurostat. (2024). Use of AI in enterprises. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Use_of_artificial_intelligence_in_enterprises (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Garaiman, D. (2003). Dreptul şi informatica. Publishing House C.H. Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y., & Ren, F. (2021). Application of artificial intelligence and wireless networks to music teaching. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, 2021(1), 8028658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güçlütürk, O. G., & Vural, B. (2024). AI red flags: Navigating prohibited practices under the AI Act. Available online: https://www.holisticai.com/blog/prohibitions-under-eu-ai-act (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Issuemonitoring.eu. (2024). Inteligența artificială—Între un cadru European complex și linii directoare simpliste românești. Available online: https://issuemonitoring.eu/inteligenta-artificiala-intre-un-cadru-european-complex-si-linii-directoare-simpliste-romanesti (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Kaplan, J. (2016). Artificial intelligence. What everyone needs to know. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher, J. (2019). Deep learning. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, V. (2024). AI and contemporary challenges: The good, bad and the scary. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 10(1), 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzweil, R. (1985). What Is Artificial Intelligence Anyway? As the techniques of computing grow more sophisticated, machines are beginning to appear intelligent—But can they actually think? American Scientist, 73(3), 258–264. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27853237 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Lavric, A., Petrariu, A. I., Mutescu, P., Coca, E., & Popa, V. (2022). Internet of Things Concept in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multi-Sensor Application Design. Sensors, 22, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, E., & Costescu, N. D. (2024). Dreptul European al internetului (2nd ed.). Publishing House Hamangiu. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, P., Goldberg, C., & Kohane, I. (2023). AI revolution in medicine. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Lidströmer, N., & Ashrafian, H. (Eds.). (2021). Artificial intelligence in medicine. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren, S. (2023). Critical theory of AI. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q., Zhu, L., Whittle, J., & Xu, X. (2024). Responsible AI. Best practices for creating trustworthy AI systems. Pearson Education. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Maida, M., Marasco, G., Facciorusso, A., Shahini, E., Sinagra, E., Pallio, S., Ramai, D., & Murino, A. (2023). Effectiveness and application of artificial intelligence for endoscopic screening of colorectal cancer: The future is now. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy, 23(7), 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, C. (2020). Artificial intelligence definitions. Stanford University. Available online: https://hai.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/2020-09/AI-Definitions-HAI.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Martínez, I. (2021). The future of the automotive industry. The disruptive forces of AI, data analytics, and digitization. Apress. [Google Scholar]