Parental Informal Occupation Does Not Significantly Deter Children’s School Performance: A Case Study of Peri-Urban Kathmandu, Nepal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Informal Employment and Consequences

3. Parental Employment and Child Education

4. Sampling, Data, and Estimation Strategy

5. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dependent Variables | Informal (All) | Informal (Small forms) | Informal (Job) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informal | −1.181 | ||

| (0.288) | |||

| Past performance | 6.892 *** | 6.868 *** | 7.481 *** |

| (3.298) | (3.279) | (3.826) | |

| School type | 6.863 * | 6.767 * | 9.036 * |

| (7.816) | (7.714) | (10.78) | |

| Wealth index | 0.689 | 0.686 | 0.724 |

| (0.214) | (0.213) | (0.225) | |

| Mother Edu | 1.199 | 1.196 | 1.254* |

| (0.148) | (0.147) | (0.159) | |

| Supporter edu | 1.704 ** | 1.699 ** | 1.659 ** |

| (0.416) | (0.414) | (0.399) | |

| informal_no3 | −1.212 | ||

| (0.319) | |||

| inf_job_1_n3 | −1.173 | ||

| (0.923) | |||

| Constant | 3.72 × *** | 3.89 × *** | 1.35 × *** |

| (1.46 × ) | (1.52 × ) | (6.10 × ) | |

| Observations | 83 | 83 | 83 |

| Pseudo | 0.378 | 0.379 | 0.374 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal job | −1.320 | |||||||

| (1.063) | ||||||||

| Past performance | 7.646 *** | 7.094 *** | 7.111 *** | 7.268 *** | 7.255 *** | 7.077 *** | 6.801 *** | 7.232 *** |

| (3.949) | (3.434) | (3.420) | (3.524) | (3.514) | (3.408) | (3.283) | (3.514) | |

| School type | 9.636 * | 7.670 * | 7.692 * | 8.328 * | 8.270 * | 7.619 * | 7.527 * | 8.178 * |

| (11.57) | (8.716) | (8.529) | (9.329) | (9.259) | (8.457) | (8.349) | (9.254) | |

| Wealth index | 0.731 | 0.715 | 0.684 | 0.718 | 0.717 | 0.686 | 0.601 | 0.719 |

| (0.228) | (0.219) | (0.212) | (0.220) | (0.220) | (0.212) | (0.208) | (0.220) | |

| Mother Edu | 1.265 * | 1.229 * | 1.205 | 1.241 * | 1.240 * | 1.204 | 1.192 | 1.239 * |

| (0.163) | (0.144) | (0.146) | (0.145) | (0.145) | (0.146) | (0.141) | (0.143) | |

| Supporter edu | 1.654 ** | 1.659 ** | 1.695 ** | 1.656 ** | 1.659 ** | 1.692 ** | 1.796 ** | 1.660 ** |

| (0.399) | (0.398) | (0.412) | (0.409) | (0.398) | (0.411) | (0.469) | (0.399) | |

| Father notax | −1.287 | |||||||

| (0.971) | ||||||||

| Mother notax | −2.064 | |||||||

| (2.225) | ||||||||

| Small firmsize | 0.966 | |||||||

| (1.460) | ||||||||

| Father nounion | −1.022 | |||||||

| (0.799) | ||||||||

| Mother nounion | −2.108 | |||||||

| (2.274) | ||||||||

| No pension | −5.404 | |||||||

| (7.499) | ||||||||

| No social security | −1.059 | |||||||

| (0.866) | ||||||||

| Constant | 9.79 × | 2.63 × | 2.94 × | 2.07 × | 2.11 × | 3.08 × | 3.06 × | 2.16 × |

| (All with ***) | (4.47 × ) | (1.04 × ) | (1.15 × ) | (8.14 × ) | (8.30 × ) | (1.20 × ) | (1.20 × ) | (8.53 × ) |

| Observations | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 |

| Pseudo | 0.375 | 0.375 | 0.378 | 0.374 | 0.374 | 0.379 | 0.390 | 0.374 |

References

- Alamneh, T., Mada, M., & Abebe, T. (2023). The choices of livelihood diversification strategies and determinant factors among the peri-urban households in Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(2), 2281047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S., & Sharma, A. (2021). Education–occupation mismatch and dispersion in returns to education: Evidence from India. Social Indicators Research, 153, 251–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S., & Sharma, A. (2024). Informality, education-occupation mismatch, and wages: Evidence from India. Applied Economics, 56(19), 2260–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputi, M., Leece, S., & Pagnin, A. (2016). The role of mother-child and teacher-child relationship on academic achievement. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14(2), 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBS/GoN. (2019). Labor force survey 2019: Employment in the informal sector (Tech. Rep.). Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Government of Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- Chudgar, A., & Shafiq, M. N. (2010). Family, community, and educational outcomes in South Asia. Prospects, 40, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S. (2015). Growing informality, gender equality and the role of fiscal policy in the face of the current economic crisis: Evidence from the Indian economy. International Journal of Political Economy, 44(4), 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Anno, R. (2022). Theories and definitions of the informal economy: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 36, 1610–1643. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, G. (2014). Workers without employers: Shadow corporations and the rise of the gig economy. Review of Keynesian Economics, 2(2), 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerry, C. (1987). Developing economies and the informal sector in historical perspective. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 493(1), 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S., & Steinberg, H. (2022). Parents’ attitudes and unequal opportunities in early childhood development: Evidence from Eastern India. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 20(3), 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gindling, T. (1991). Labor market segmentation and the determination of wages in the public, private-formal and informal sectors in San-Jose, Costa-Rica. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 39(3), 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P., & Sahn, D. E. (2009). Cognitive skills among children in Senegal: Disentangling the roles of schooling and family background. Economics of Education Review, 28(2), 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunther, I., & Launov, A. (2012). Informal employment in developing countries: Opportunity or last resort? Journal of Development Economics, 97(1), 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haanwinckel, D., & Soares-Mada, R. (2021). Workforce Composition, Productivity, and Labour Regulations in a Compensating Differentials Theory of Informality. The Review of Economic Studies, 88(6), 2970–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J., & Todaro, M. (1970). Migration, unemployment and development: A two sector analysis. The American Economic Review, 60(1), 126–142. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1807860 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Heckman, J. J., Lochner, L. J., Todd, P. E., Hanushek, E., & Welch, F. (2006). Earnings Functions, Rates of Return, and Treatment Effects: The Mincer Equation and Beyond. In Handbook of the economics of education (Vol. 1, pp. 307–458). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justino, P. (2007). Social Security in Developing Countries: Myth or Necessity? Evidence from India. Journal of International Development, 19, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jæger, M. M. (2012). The Extended Family and Children’s Educational Success. American Sociological Review, 77(6), 903–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KC, S. (2020). Internal Migration in Nepal. In M. Bell, A. Bernard, E. Charles-Edwards, & Y. Zhu (Eds.), Internal migration in the countries of asia (pp. 299–318). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishwar, S., & Alam, K. (2021). Educational mobility across generations of formally and informally employed: Evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Educational Development, 87, 102505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolm, A.-S., & Larsen, B. (2016). Informal unemployment and education. IZA Journal of Labor Economics, 5, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, W. (1999). Does informality imply segmentation in urban labor markets? Evidence from sectoral transitions in Mexico. World Bank Economic Review, 13(2), 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, W. (2004). Informality revisited. World development, 32(7), 1159–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurin, E. (2002). The impact of parental income on early schooling transitions: A re-examination using data over three generations. Journal of public Economics, 85(3), 301–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaig, B., & Pavcnik, N. (2015). Informal Employment in a Growing and Globalizing Low-Income Country. American Economic Review, 105(5), 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, R. (2008). Skills and productivity in the informal economy (Report). Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ilo/ilowps/994131423402676.html (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Parajuli, S., Paudel, U. R., Devkota, N., Gupta, P., & Adhikari, D. B. (2021). Challenges in transformation of informal business sector towards formal business sector in Nepal: Evidence from descriptive cross-sectional study. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology, 39(2), 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxson, C., & Schady, N. (2007). Cognitive development among young children in Ecuador: The roles of wealth, health, and parenting. Journal of Human Resources, 42(1), 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattri, M., & Watkins, K. (2019). Child labour and education—A survey of slum settlements in Dhaka (Bangladesh). World Development Perspectives, 13, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungo, P., Casal, B., Rivera, B., & Currais, L. (2015). Parental education, child’s grade repetition and the modifier effect of cannabis use. Applied Economics Letters, 22(3), 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, V. J., & Parinduri, R. A. (2016). What happens to children’s education when their parents emigrate? Evidence from Sri Lanka. International Journal of Educational Development, 46, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyanti, A. M. (2020). Informality and the education factor in Indonesian labor. Journal of Indonesian Applied Economics, 8(2), 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. (1976). The efficiency wage hypothesis, surplus labor, and the distribution of labour in LDCs. Oxford Economic Papers, 28(2), 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassie Wegedie, K. (2018). Determinants of peri-urban households’ livelihood strategy choices: An empirical study of Bahir Dar city, Ethiopia. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1562508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa-Parajuli, R. (2015). Determinants of Informal Employment and Wage Differential in Nepal. Journal of Development and Administrative Studies, 22(1–2), 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa-Parajuli, R., Tamrakar, A., & Timsina, M. (2020). Informality and Children’s School Performance in Nepal. Journal of Development and Administrative Studies, 28(1–2), 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, K., Chen, F., & Desai, S. (2018). Mothers’ work patterns and Children’s cognitive achievement: Evidence from the India Human Development survey. Social Science Research, 72, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C. C., & Round, J. (2007). Beyond negative depictions of informal employment: Some lessons from Moscow. Urban Studies, 44(12), 2321–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

| Child School | Household heads were asked whether their child performed batter, |

| Performance | remained the same, or improved their school performance relative to last year and this year. We label this as “degraded” and coded it as 1 if the score decreased, and “zero” if unchanged or improved. |

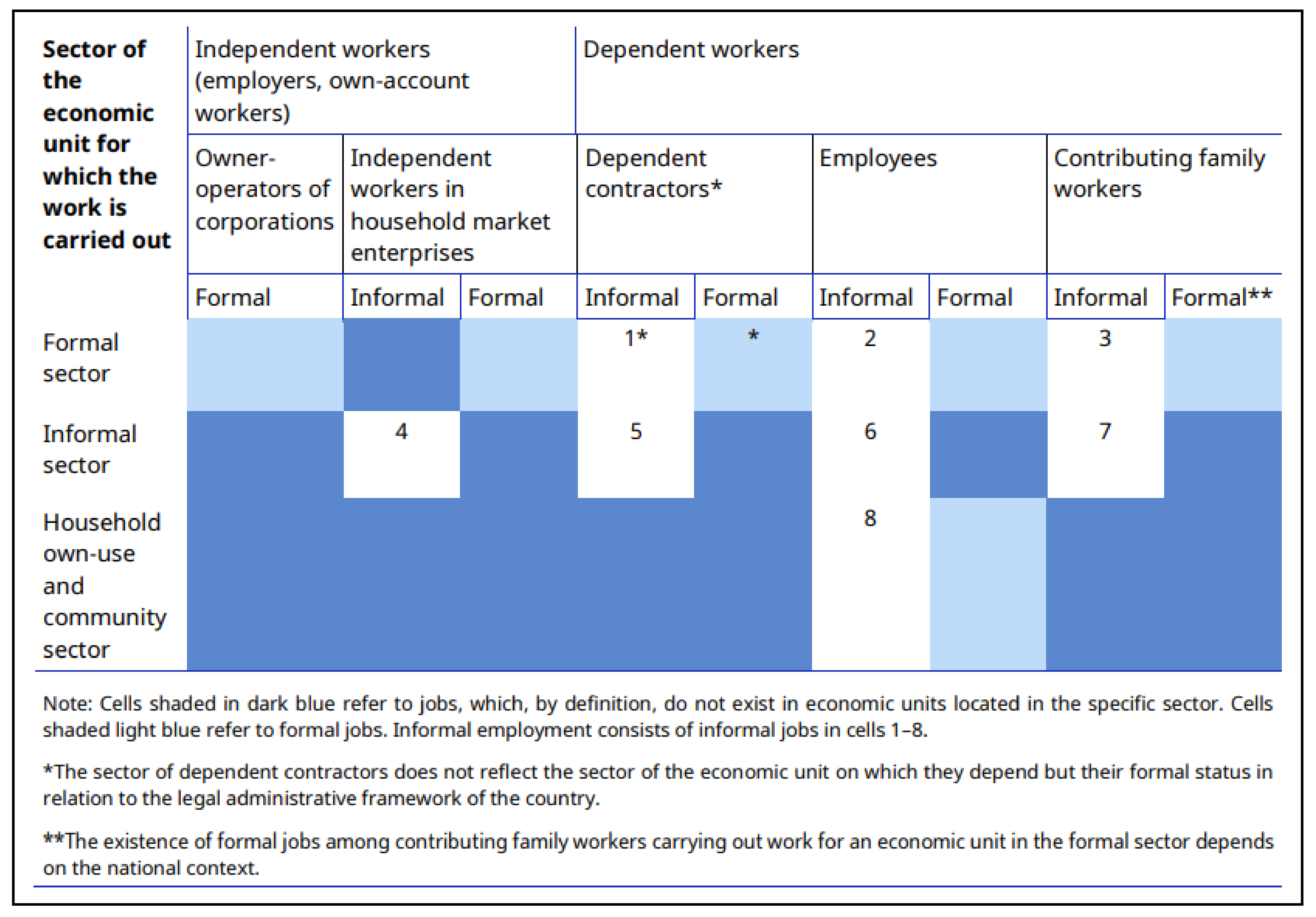

| Informality | Based on the ILO definition, Figure 1, informality was defined by seven indicators; the prevalence of at least one is informal. The indicators are pay tax or not (1.Mother and 2. Father), firm size of the parents (3), no union membership (4. Father and 5.Mother), pension (6), and social security (7). |

| Informal N3 | This variable excludes firm size as a determinant, unlike Informal, where larger firms are formal and smaller ones informal. |

| Informal jobs N3 | This variable is the same as Informal jobs but excludes the third determinant, as explained above, which is size of the firm. |

| Father notax | This variable indicates whether the father pays any direct tax related to his occupation. If no tax is paid, the occupation is considered informal, otherwise formal. |

| Mother notax | Similarly to Father notax, this variable indicates whether the mother works and pays tax. If no tax is paid, the occupation is considered informal. |

| Small firmsize | This determinant is considered the third determinant of informality, where a small firm is informal, and formal otherwise. |

| Father nounion | This variable indicates whether the father is part of a labor union. If the father is part of any form of organized labor union, this is considered formal, otherwise informal. |

| Mother nounion | Similarly to Father nounion, this variable checks whether the mother is formally a member of any labor union organization. |

| No pension | This variable indicates whether the father or mother will receive any pension facility after being terminated from their job. If a pension is received, the employment is considered formal, otherwise informal. |

| No social security | This variable records whether any social security facility covers the parents. If covered, the employment is formal, otherwise informal. |

| Past performance | Parents were asked about their child’s school performance in the previous year (Improved and remained the same are `1’ and `0’ otherwise). |

| School type | Child’s school type is coded as 1 for private and 0 for public. |

| Wealth index | Wealth index is based on household durables using PCA scores. |

| Mother Edu | This variable records the mother’s years of schooling. |

| Supporter edu | This variable records the years of schooling of family members who assist with studying at home. |

| Variables | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender dummy (Male 1, and 0 otherwise) | 0.4861 | 0.5033 | 0 | 1 |

| Age of the children | 9.4306 | 3.4998 | 1 | 15 |

| School dummy (Private 1, 0 otherwise | 0.2639 | 0.4438 | 0 | 1 |

| Family Size | 4.8194 | 1.3250 | 1 | 9 |

| Number of children in family | 2.0417 | 0.8297 | 1 | 5 |

| Household wealth index | −0.3101 | 1.5733 | −2.12 | 3.64 |

| Parental occupation dummy (Informal 1, 0 otherwise) | 0.3750 | 0.4875 | 0 | 1 |

| Past performance improved or remain the same is 1 | 0.7500 | 0.4361 | 0 | 1 |

| School performance degraded is 1 | 0.2892 | 0.4501 | 0 | 1 |

| Income category (Quintile) | 2.9306 | 1.0790 | 1 | 5 |

| Children’s daily time spent for study at home (min) | 77.2917 | 55.0220 | 0 | 220 |

| Own Efforts and Parental Support | Formal (1) (n = 51) | Informal (2) (n = 32) | Difference (1) − (2) | t-Value (n = 83) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study time allocated by the | 80.33 | 72.22 | 8.11 | 0.60 |

| children at home (Minutes/Daily) | (8.82) | (9.23) | (13.46) | (p = 0.27) |

| Parental support at home for | 41.22 | 53.33 | −12.11 ** | −1.89 |

| study (Minutes/Daily) | (3.26) | (6.27) | (6.42) | (p = 0.03) |

| Mother’s level of education | 6.62 | 10.52 | −3.90 *** | −4.22 |

| (Years of Schooling) | (0.56) | (0.74) | (0.92) | (p = 0.00) |

| Father’s level of education | 6.71 | 10.56 | −3.84 *** | 3.77 |

| (Years of Schooling) | (0.60) | (0.85) | (1.02) | (p = 0.00) |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal job | −0.0390 | |||||||

| (0.109) | ||||||||

| Past performance | 0.292 *** | 0.287 *** | 0.284 *** | 0.288 *** | 0.288 *** | 0.283 *** | 0.277 *** | 0.287 *** |

| (0.0666) | (0.0650) | (0.0646) | (0.0650) | (0.0649) | (0.0646) | (0.0645) | (0.0654) | |

| School type | 0.325 ** | 0.298 ** | 0.296 ** | 0.308 ** | 0.307 ** | 0.293 ** | 0.291 ** | 0.305 ** |

| (0.151) | (0.149) | (0.145) | (0.145) | (0.145) | (0.145) | (0.145) | (0.148) | |

| Wealth index | −0.0449 | −0.0490 | −0.0550 | −0.0481 | −0.0483 | −0.0545 | −0.0734 | −0.0480 |

| (0.0444) | (0.0444) | (0.0444) | (0.0439) | (0.0440) | (0.0441) | (0.0499) | (0.0439) | |

| Mother edu | 0.0337 ** | 0.0302 * | 0.0271 | 0.0314 * | 0.0312 * | 0.0268 | 0.0253 | 0.0311 * |

| (0.0170) | (0.0162) | (0.0168) | (0.0160) | (0.0160) | (0.0168) | (0.0164) | (0.0159) | |

| Supporter edu | 0.0722 ** | 0.0741 ** | 0.0765 ** | 0.0733 ** | 0.0735 ** | 0.0760 ** | 0.0845 ** | 0.0736 ** |

| (0.0348) | (0.0352) | (0.0354) | (0.0360) | (0.0349) | (0.0351) | (0.0379) | (0.0350) | |

| Father notax (1) | −0.0383 | |||||||

| (0.120) | ||||||||

| Mother notax (2) | −0.125 | |||||||

| (0.214) | ||||||||

| Small firmsize (3) | 0.0049 | |||||||

| (0.215) | ||||||||

| Father nonunion (4) | −0.0032 | |||||||

| (0.114) | ||||||||

| Mother nonunion (5) | −0.129 | |||||||

| (0.217) | ||||||||

| No pension (6) | −0.346 | |||||||

| (0.335) | ||||||||

| No social security (7) | −0.0084 | |||||||

| (0.122) | ||||||||

| Observations | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 |

| Pseudo | 0.375 | 0.375 | 0.378 | 0.374 | 0.374 | 0.379 | 0.390 | 0.374 |

| Proxy Mean VIF | 1.35 | 1.27 | 1.31 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 1.28 | 1.32 | 1.23 |

| Dependent Variables | Informal (All) | Informal (No Small Form) | Informal Job (Large Form) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informal | −0.0243 | ||

| (0.0360) | |||

| Past performance | 0.281 *** | 0.281 *** | 0.290 *** |

| (0.0647) | (0.0647) | (0.0662) | |

| School type | 0.281 * | 0.278 * | 0.317 ** |

| (0.151) | (0.151) | (0.151) | |

| Wealth index | −0.0544 | −0.0548 | −0.0465 |

| (0.0449) | (0.0448) | (0.0443) | |

| Mother edu | 0.0264 | 0.0261 | 0.0326 * |

| (0.0174) | (0.0174) | (0.0169) | |

| Supporter edu | 0.0777 ** | 0.0772 ** | 0.0730 ** |

| (0.0358) | (0.0356) | (0.0348) | |

| Informal no3 | −0.0281 | ||

| (0.0386) | |||

| Informal job no3 | −0.0227 | ||

| (0.110) | |||

| Observations | 83 | 83 | 83 |

| Pseudo | 0.378 | 0.379 | 0.374 |

| Proxy Mean VIF | 1.35 | 1.34 | 1.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thapa-Parajuli, R.; Bhattarai, S.; Pokharel, B.; Timsina, M. Parental Informal Occupation Does Not Significantly Deter Children’s School Performance: A Case Study of Peri-Urban Kathmandu, Nepal. Economies 2025, 13, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13040095

Thapa-Parajuli R, Bhattarai S, Pokharel B, Timsina M. Parental Informal Occupation Does Not Significantly Deter Children’s School Performance: A Case Study of Peri-Urban Kathmandu, Nepal. Economies. 2025; 13(4):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13040095

Chicago/Turabian StyleThapa-Parajuli, Resham, Sujan Bhattarai, Bibek Pokharel, and Maya Timsina. 2025. "Parental Informal Occupation Does Not Significantly Deter Children’s School Performance: A Case Study of Peri-Urban Kathmandu, Nepal" Economies 13, no. 4: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13040095

APA StyleThapa-Parajuli, R., Bhattarai, S., Pokharel, B., & Timsina, M. (2025). Parental Informal Occupation Does Not Significantly Deter Children’s School Performance: A Case Study of Peri-Urban Kathmandu, Nepal. Economies, 13(4), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13040095