1. Introduction

The tourism experience is increasingly a collective experience based on sociability (

Amirou, 2008) and authenticity (

Huang et al., 2023). Interacting, making new acquaintances and building a network of friendships are all major aspects of travel. The tourism sector is seeing the emergence of innovative new forms of travel, such as couchsurfing, that encourages encounters between visitors and residents or both urban and rural areas (

Santos et al., 2020), which are expected to impact rural development.

Couchsurfing is a form of tourism that appeared in 2004 and is gaining in popularity, attracting millions of members every year. Couchsurfing involves staying for free with residents who make contact via a hospitality network called “couchsurfing.org” (

Decrop & Degroote, 2014;

Wang, 2024). Thanks to this network, travellers can contact other people and can host them or use their “couch” for free (

Consalter, 2024). According to

Sacks (

2011), the couchsurfing experience satisfies the expectations of travellers who want to rub shoulders with the locals, explore the country in a more active and authentic way and immerse themselves in a whole system of habits and operations. This search for authenticity is expressed in the form of a return to nature and authentic values or disinterested exchanges with local people (

Huang et al., 2023;

Bao, 2023).

The couchsurfing experience is therefore a potential source of multiple values for travellers (

Rafi et al., 2023). However, to the best of researchers’ knowledge, there is no empirical research that has identified the perceived values of the couchsurfing experience, and most research focuses solely on the motivations for couchsurfing and the reasons why travellers choose to stay with strangers (

Decrop & Degroote, 2014;

Wang, 2024;

Consalter, 2024). This research addresses the values that couchsurfers perceived in their tourism experience. Thus, it is worthwhile to construct a scale in order to assess the perceived values of the couchsurfing phenomenon. Understanding the tourism experience should contribute to tourism development, particularly in rural areas, where tourism is critical to the local community and its economy. In addition, this should help in understanding tourist preferences and experiences in tourism development (

Chomać-Pierzecka & Stasiak, 2023). Couchsurfing could be a tool for enhancing domestic tourism and rural development due to its non-commercial aspect, which is needed by many travellers (

Chomać-Pierzecka & Stasiak, 2023).

The purpose of our exploratory study is to identify the dimensions of the perceived value of a couchsurfing experience and to propose a reliable and valid measurement to understand the traveller experience in this type of tourism. Following the steps of Churchill’s paradigm (1979), our research is structured as follows: definition of the domain of the construct, generation of a list of items and validation of the structure of the scale through two data collections. The next parts of the paper start with reviewing related studies. It then shows the study methodology by discussing Churchill’s paradigm and the use of missed methods. It then shows the results of the qualitative and quantitative study. The results are then discussed, and implications are elaborated. The paper ends with the final remarks and presenting the limitations and future study opportunities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Couchsurfing: A Form of Participative Tourism

Couchsurfing is characterised by the search for experience, fulfilment and sociability through increased social interaction (

Cao et al., 2022). According to

Coquin (

2008), individuals interested in couchsurfing share a common interest in meeting people from other countries with a combination of respect and discovery. Couchsurfing is characterised by the involvement of residents in welcoming tourists: guided tours, walks, sea trips, etc. (

Coquin, 2008). According to

Sacks (

2011) and

Huang et al. (

2023), a new sharing economy is emerging. This form of tourism allows individuals to live their experience to the full: sharing something with the host (a walk, a dish, a story or even a coffee), respecting everyone’s differences, participating by spending time with their host or surfer, or connecting with the place and the people they meet to learn from the outside world. In addition, it can be seen as a utopia of socio-romantic sharing (

Hellwig et al., 2014). The latter is characterised, on the one hand, by the importance of shared experiences rather than on material sharing and, on the other hand, by the development and appropriation of calculated and temporary social relationships. This type of tourism is important for rural development.

Within this context, the phenomenon of couchsurfing, which emerged in 2004, has gained substantial traction, attracting millions of members annually. Couchsurfing has evolved into a global community of over 14 million members spread across more than 200,000 cities. It has facilitated more than 500,000 events worldwide, fostering connections and cultural exchanges among travellers and hosts (

Couchsurfing.com, 2025). This platform has the particularity to be based on voluntary participation and non-monetary exchange. According to the latest statistics made by the Couchsurfing.com site in September 2024, the couchsurfing experience has slightly more appeal among men (55.69%) with an age group of 25–34 years old than women (

Couchsurfing.com, 2025).

Couchsurfing could also be considered a practice of slow tourism (

Vera et al., 2024), which is characterised by a different behaviour and a different rhythm of life that manifests itself in the slow, deep, sincere and authentic discovery of a place, its inhabitants and their culture (

Matos-Wasem, 2004). Travellers adopting couchsurfing are enjoying a stay in human-scale facilities that are open to the world but very much imbued with their locality (

Priskin & Sprakel, 2008).

2.2. Perceived Value

Marketing literature shows that perceived value has mainly been approached through three different approaches: firstly, purchase value, which reflects the overall assessment of the usefulness of an offer following compensation between perceived benefits and sacrifices (

Zeithaml, 1988); secondly, the consumption value, which refers to the relative preference characterising the experience of contact between a subject and an object, and results from the experience of consuming/possessing a good. It follows an experiential approach and presents a multifaceted vision of value (

Bourliataux-Lajoinie & Rivière, 2013) based on Holbrook’s approach (1994) which is the most cited in the perspective of the typology of dimensions of consumer value. Three axes are then presented to differentiate them: value oriented towards oneself/others, active/reactive value and extrinsic/intrinsic value. The intersection of these three dimensions of value constitutes a typology of value (

Table 1), and finally there is the mixed approach to value, which combines the analytical framework of purchase value and the wealth of components of consumption value. A great deal of research has proposed studying value in relation to the consumption experience and has defined and measured it in a multidimensional way (

Jarrier et al., 2019). Value is therefore a consumer’s affective reaction to the consumption object.

Perceived value has mainly been studied in the context of shopping experiences (

Mathwick et al., 2001;

Filser & Plichon, 2004). The results have shown that the elements of the consumption experience valued by consumers are different. Some dimensions are cognitive (knowledge, expertise), while others are experiential and emotional (experiential stimulation, enchantment) or social (exchange, sharing). The work of

Sanchèz et al. (

2006),

Bonnefoy-Claudet (

2011),

Gallarza and Saura (

2006) and

Williams and Soutar (

2009) complements these in the tourism sector, such as ski resorts (

Bonnefoy-Claudet, 2011), travel agencies and adventure tourism products (

Williams & Soutar, 2009).

It turns out that few empirical studies exist in tourism focusing on cases such as the couchsurfing experience, and the few works that have studied this phenomenon have focused solely on exploring its motivations (

Decrop & Degroote, 2014;

Zgolli & Zaiem, 2018;

Vera et al., 2024;

Bao, 2023), but no study has been conducted on the nature of this value. However, the couchsurfing experience is very rich, diverse and multi-faceted as indicated by exploratory qualitative research on the subject (

Chen, 2018;

Liu, 2012;

Zaki, 2015). Following the elements mentioned, it seems clear that the marketing literature is facing an absence of instruments that measure the perceived values of the couchsurfing experience.

2.3. Couchsurfing and Rural Development

Approaching the subject of couchsurfing from the perspective of its sustainability implies considering it in the prism of sustainable development, particularly in rural development. According to

Huang et al. (

2023), couchsurfing is a reaction to past practices and leaves room for a new vision of development dynamics or activities that do not conflict and are embodied in the specific products of sustainable tourism.

Coquin (

2008) argued that couchsurfing in a rural context strengthens, nurtures and encourages the community’s ability to maintain its traditional skills. According to

SEATM (

2000), the rural environment is an object worthy of interest. If the awareness of couchsurfers contributes to the ecosystem, it can also be considered as a vector of information, and couchsurfers combine learning with relaxation. However, this tourist offering can only be based on a quality environment. In rural areas, the presence of couchsurfers and their practices in contact with nature gives them a central place. Thus, the phenomenon of couchsurfing is mainly about protecting and managing natural resources in a rural context, but these actions go beyond the natural framework to highlight its relationship with hosts (

François, 2004). This makes the exchange of values between visitors and hosts economic, social and cultural.

3. Methodology

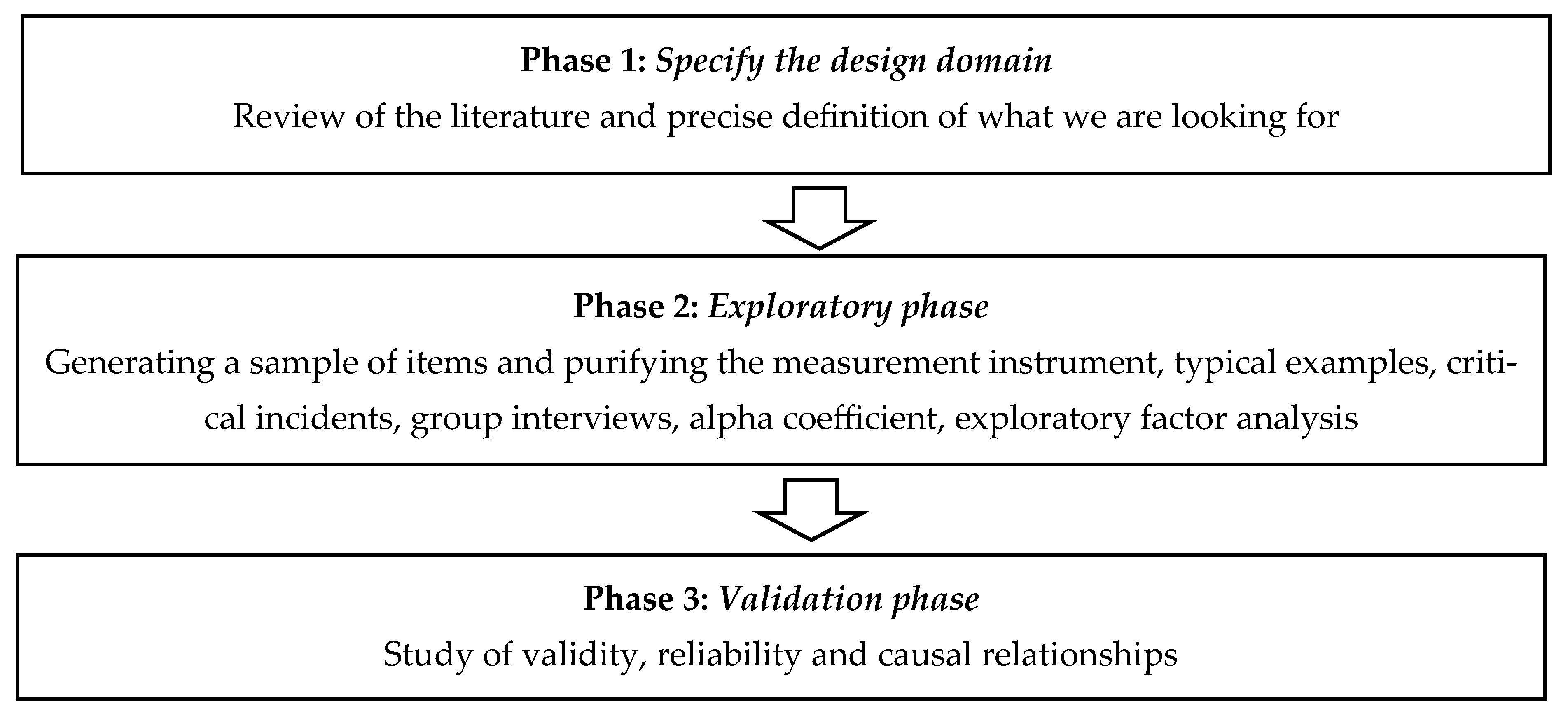

When constructing a measurement scale, it is undeniable that a purely scientific approach must be followed to protect the validity and relevance of the construct being measured. In this respect, it is important to remember that the primary role of a scale is to replicate the best original assessment possible of the phenomenon in question (

Igalens & Roussel, 1998). Churchill’s paradigm (1979) seems to be concerned with this task. Churchill’s paradigm seems to be concerned with this task through the successive use of validity tests (the measurement instruments chosen must provide the best possible understanding of the phenomenon being measured) and reliability tests (if a phenomenon is measured several times with the same instrument, the same result must always be obtained). To condense random error (Ea) and systematic error (Es),

Churchill (

1979) outlines an approach, which is summarised in

Figure 1, for developing measurement scales capable of ensuring that the value obtained (M) is as representative as possible of the true value (V) of the phenomenon being measured. Therefore, to construct the measurement scale for the couchsurfing experience, we are going to look at the various tests of content validity, in particular convergent validity and discriminant validity, the reliability of the measurements and the dimensionality of the construct being measured.

Note: The “true score model” of Churchill’s paradigm (1979) is presented as follows:

where

M = measurement obtained;

V = true value: this is the ideal measurement. This is the measure that would correspond perfectly to the phenomenon under study; it is most often impossible to reach directly and constitutes the horizon of empirical measurement;

Es = systematic error: this type of error arises from the fact that the measuring instrument may have a systematic deviation from the phenomenon being studied (for example, a scale that displays 900 g instead of 1 kg);

Ea = random error: the phenomenon measured by a single instrument may be subject to random factors, such as circumstances and the mood of the people questioned.

3.1. Generating the List of Items

To identify various facets of the perceived value of a couchsurfing experience and following our literature review, the first phase of this research, a qualitative study, included semi-structured interviews with a sample of 26 European couchsurfers (containing twelve French, nine Italian, four Belgian and one German) in their capacity as guests. They were identified via the research team network. Our participants were selected via forums and blogs relating to couchsurfing (Oiseaurose.com, TripAdvisor, Couchers.org). This number was decided once there was data saturation, and no more new thoughts were added. These are people who have had recent experience of using the couchsurfing network. Our sample is heterogeneous in terms of gender (as many women as men), age (from 18 to 55), and professions (students, employees, professionals, artists, etc.). These people then referred us to others who, in turn, had tried couchsurfing, enabling us to complete our sample using the “snowball” principle (

Ritchi, 2013). European couchsurfers were purposively chosen because they are the most active on couchsurfing platforms and Facebook pages. Furthermore, according to statistics from the website of Couchsurfing.org, couchsurfers are mainly from Western industrialised countries, with Europe accounting for approximately half of all members worldwide (

Priskin & Sprakel, 2008). The interview guide was built around three main themes: (1) how to organise a trip in general, (2) the reasons why travellers choose couchsurfing and (3) the experience and feelings of couchsurfers (

Appendix A).

This study relied on common language, because it contains a treasure trove of social quintessence. The answers gathered during the interviews enabled us to list a certain number of situations describing the experience, lived experience and feelings of couchsurfers. Drawing on the redundancy of specific terms and words mentioned by participants, we have summarised them in

Table 2.

The thematic analysis adopted to analyse responses enabled us to identify three groups corresponding to three lexical fields. These three groups are organised based on their order of significance as identified by participants. Once full transcriptions of the speeches had been made and after thematic content analysis, we were able to generate 108 items of connivance with the couchsurfing experience, based on the three dimensions mentioned above in

Table 2. This classification reminds us of that of

Holbrook (

1999), who, based on his survey, distinguished four dimensions:

- -

Intrinsic, self-oriented values: exploration, personal fulfilment;

- -

Extrinsic self-oriented values: economic, freedom, etc.;

- -

Intrinsic values oriented towards others (altruistic): societal, cultural, solidarity;

- -

Extrinsic values oriented towards others: social

It should be pointed out that the categorisation we have highlighted is based on the results of

Holbrook (

2009),

Sanchèz et al. (

2006),

Bonnefoy-Claudet (

2011),

Gallarza and Saura (

2006) and

Williams and Soutar (

2009), who have worked on perceived values in tourism contexts. In order to be even more certain of our categorisation, we submitted this list of 108 items to three experts (two tourism marketing professors with work on alternative tourism and a tourism expert) and asked them to classify them according to the three dimensions explained above. Any disagreements between the three experts were settled by calling in a fourth judge (a marketing professor). At the end of this procedure and after eliminating redundancies, sixty-eight items, measuring the three dimensions mentioned above, i.e., economic, exploration and socio-cultural values, were retained. Once the principal component analysis had been carried out, we eliminated the items that revealed factorial contributions of less than 0.5.

3.2. Purification and Validation of the Measurement Scale

The second phase of the research, the quantitative study, included two steps. Step number 1, the administration of a questionnaire to a sample of 102 couchsurfers, was based on 68 items developed from the first phase. We undertook an exploratory factor examination and a reliability analysis using SPSS version 23 and retained only nine items divided into three dimensions linked to the value of couchsurfing. These were economic, exploration and socio-cultural. Step number 2 was carried out on a new convenience sample of 243 Europeans selected from forums, blogs and Facebook pages relating to couchsurfing (Oiseaurose.com, TripAdvisor, Couchers.org). It should also be pointed out that we chose to keep only those dimensions that had good psychometric qualities (for example, we were obliged to eliminate societal and emotional values as they did not meet statistical standards), while for others we chose to merge them, such as the social value and the cultural value.

3.2.1. The First Dimension: Economic Value

The first dimension, “economic value”, containing three items, which is explained by the free nature of this mode of tourism, accounts for 78.446% of the total variance explained (

Table 3).

Furthermore, the KMO ratio (

Table 4) for the data consistent with this dimension is of the order of 0.707 for the final sample, which authenticates the relevance of the factorial analysis. This KMO reveals that the data relating to the measurement of such dimension offer themselves well to factor analysis.

The reliability examination of the final sample shows a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.862 (

Table 5 and

Table 6). This shows that the consistency of this dimension is very satisfactory. This result is endorsed by Evrard et al., who state that an alpha coefficient between 0.60 and 0.70 is acceptable (

Evrard et al., 2000).

3.2.2. The Second Dimension: Exploration Value

The value exploration, alluding to the disconnection that the couchsurfer makes through surprise and adventure trips, explains around 78% of the total variance (see

Table 3). This dimension shows a KMO indicator (

Table 4) of around 0.718 for the final sample, which means that this dimension lends itself well to factor examination. Furthermore, the reliability displays a Cronbach’s alpha (

Table 5) of 0.859. Here we can see that the consistency of this dimension is very satisfactory (

Table 6).

3.2.3. The Third Dimension: Socio-Cultural Value

The third dimension is “socio-cultural value”, which manifests itself in sociability and exchange between couchsurfers and hosts, as well as personal enrichment and cultural mixing, explaining around 83% of the total variance. The KMO and Cronbach’s alpha, respectively, show the following indices (0.729) and (0.897), which indicates the factorizability and good internal consistency of the data for this dimension (

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6).

4. Measurement Results

Once the data had been collected using the study questionnaire, we carried out a dual examination. The first was an exploratory analysis (see above) to evaluate the quality of the measurement scale with a view to purifying the research questionnaire. For this we used a principal component analysis (PCA) accompanied by an internal consistency analysis. The second analysis is of a confirmatory type, likely to validate the dimensions retained from the exploratory analysis. In addition, this analysis will study the causal relationships between the dimensions, using structural equation models. To achieve this, we used statistical software (Amos, version 23).

The interpretation confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) findings started with looking at the fitness indices. These include the Chi

2/ddl parsimony index, which must be less than 5 (

Pedhazur & Schmelkin, 1991); the SRMR, which must be less than 0.05 and the RMSEA, which must be less than 0.08 and, if possible, 0.05 (

Roussel, 2005). Next come the incremental indices with a threshold value of 0.90 (

Bentler & Bonett, 1980). Additionally, there are the parsimony indices via the normalised (χ

2).

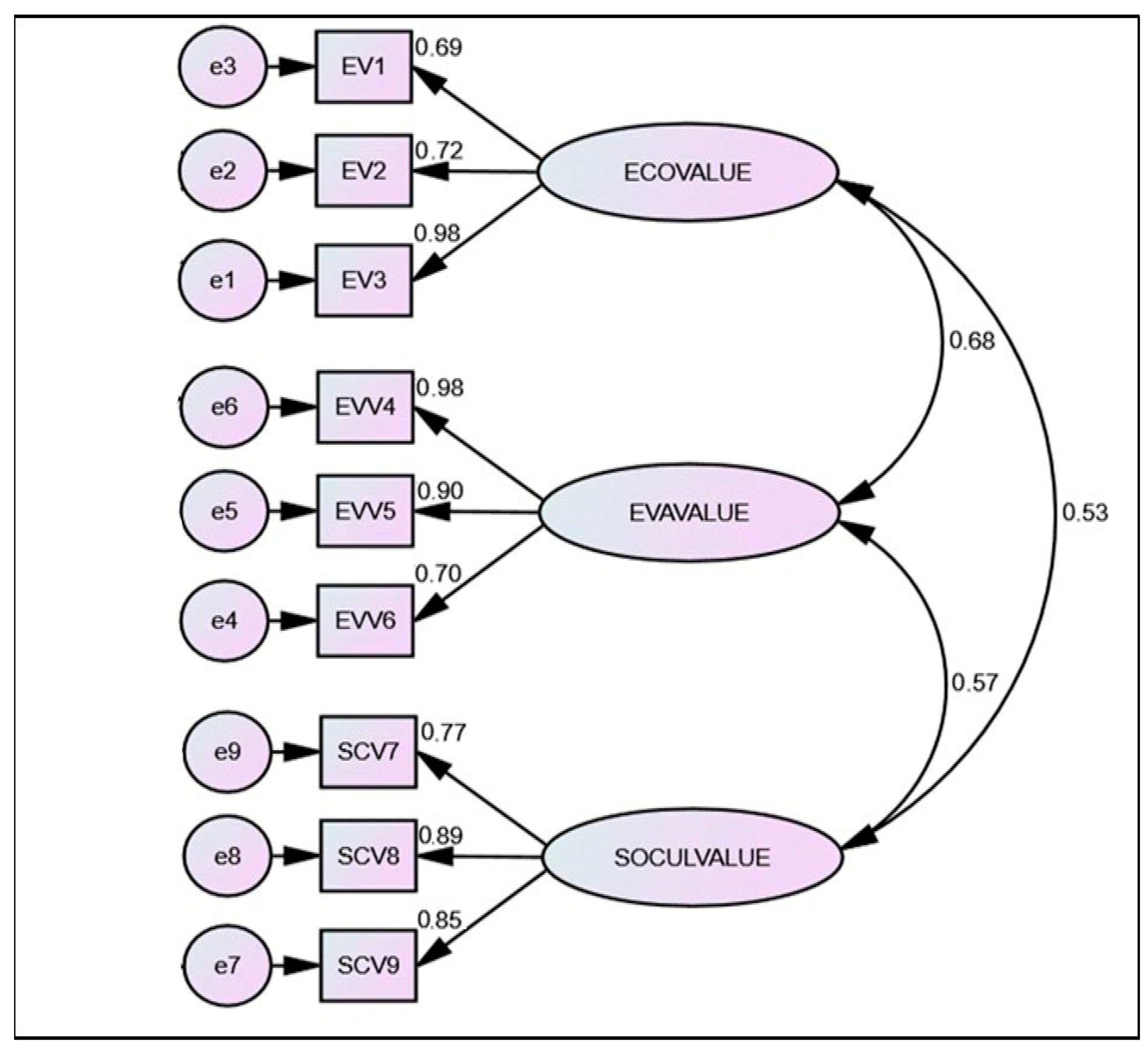

The findings of the first-order CFA showed a satisfactory data fitness (

Table 7,

Figure 2), which meets suggested standards (

Roussel et al., 2005). They show a chi-square related to its degree of freedom χ

2/ddl (3.136). This share is considered acceptable as it is below 5. Furthermore, the RMSEA value equals 0.094, i.e., close to zero; it shows us that the fit is satisfactory. Values, e.g., NFI = 0.958, TLI = 0.947 and CFI = 0.970, also confirmed excellent fit.

Model fit: (χ2 (20, N = 243) = 62.721 p < 0.001, normed χ2 = 3.136, RMSEA = 0.094, RMR = 0.050, GFI = 0.947, AGFI = 0.882, SRMR = 0.0347, CFI = 0.970, TLI = 0.947, NFI = 0.958, RFI = 0.924, IFI = 0.971, *** p < 0.001.

4.1. The Results of CFA

The items on the scale had minimum and maximum values ranging from 1 to 5. Means varied between 3.66 and 4.04, with standard deviation values ranging from 1.094 to 1.302 (see

Table 7, column SD), confirming that collected data are normally distributed (

Bryman & Cramer, 2012).

Two indicators were used to assess the normal distribution or the Gaussian curve. These indicators are skewness and kurtosis coefficients. Firstly, the skewness is able to show whether the observations are evenly distributed about the mean (

Evrard et al., 2000). The Kurtosis indicator reflects the distribution curve (

Evrard et al., 2000). As far as current research is concerned, both indicators show that our data did not interrupt the normality assumption (

Kline, 2015). In this respect, this confirms that the data are fairly distributed (

Table 7 and

Figure 2). Responses had a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 5, and the mean score varied between 3.66 (SD = 1.302) and 4.04 (SD = 1.31) (

Table 7).

4.2. Convergent and Discriminant Validity of Measurements

To ensure that the scale items, which are supposed to measure the same phenomenon, were correlated, we used convergent validity. This was achieved by means of the CR, which had to be above 0.7, and the AVE, which had to be above 0.5. The results (

Table 8) demonstrate that convergent validity was confirmed for all the dimensions of the measurement scale (

Joreskog, 1988). To check whether the theoretical adopted dimensions were also distinct in practice, discriminant validity was thus checked. Therefore, we checked whether the square root of the AVE of a dimension is higher than the associations it shares with the other dimensions.

The results in

Table 8 show that discriminant validity was verified for the three dimensions as well as for the scale in question. The CRs for economic (0.844), exploration (0.980) and socio-cultural (0.874) values were well above 0.7. Moreover, the average extracted variance (AVE) scores for economic value (0.649), exploration value (0.750) and socio-cultural value (0.698) are significantly greater than 0.5, which is the second piece of evidence that discriminant validity has been achieved (

Hair et al., 2014). Regarding the measurement scale. counting all its dimensions, the CR indicates a value of 0.954 > 0.7, and the AVE displays a value of 0.699 > 0.5. Hence, discriminant validity was confirmed (

Hair et al., 2014). In addition, the intercorrelation values for each dimension must not be higher than the values on the diagonal confirming the square roots of the AVE (

Table 8, in bold).

5. Discussion

Following

Holbrook (

2009), we can define perceived value as all the benefits resulting from their experiences. These benefits can be not only utilitarian, relating to efficiency (free accommodation, savings, speed, information), but also hedonic, relating to exploration and enjoyment, which translates into playfulness. Our exploratory study has confirmed the presence of other types of value that are rarely taken into account in research on the perceived value of a tourism experience. This experience is critical for tourism development, particularly in rural areas.

The results of our research show that economic value is of great importance to consumers in terms of their experience (78.178% of the total variance explained). Consumers are attracted to efficient forms of tourism based on practicality and cost reduction. In addition, and in their quest for pleasure, couchsurfers are looking for an experience that allows them to evade and cut themselves off from everyday life (78.178% of the total variance), which concurs with the study of

Vera et al. (

2024) who prove that the desire to evade from the ordinary, from traditional tourism, with the aim of living a personal moment and an authentic experience close to reality is one of the main motivations for couchsurfing. In terms of socio-cultural value, our study shows that couchsurfing helps to create a social link in the sense that it makes couchsurfers interact and meet people around the world while discovering other cultures that enhance their knowledge about the country or region visited through accommodation with a local (83.011% of total variance). In this respect,

Bourliataux-Lajoinie and Rivière (

2013) confirm that the value of the link is much more important than the value of the good itself: the good contributes to the development of links between people. The same is true of

Vera et al. (

2024), who showed that for the Portuguese it is not financial motivation that is most important but rather the creation of social ties. In addition, several respondents criticised traditional forms of accommodation for the lack or absence of contact with the local population and the limited opportunity to discover the country in an authentic and more sincere way, with its traditions and customs (

Decrop & Degroote, 2014). These results explicitly show the synergistic effect that the different facets of value can have on each other. In other words, the more sources of value the tourism experience has, the greater its appeal.

6. Implications

From a theoretical point of view, our research addresses the lack of a multidimensional measurement scale in the literature to capture the different aspects of the perceived value of a couchsurfing experience. Similarly, our research enables us to prove once again the value of placing the couchsurfing experience in a socio-cultural perspective, which is vital for tourism development, particularly rural development.

From a managerial point of view, this scale has the advantage of being easy to administer in the field and to adapt to other types of experience. It is also an indicator that can be used to assess the effectiveness of differentiation strategies by displaying the anticipated values through clear and explicit positioning. To achieve this, it seems necessary for tourism managers to renew themselves and offer new products and services if they wish to remain competitive and continue to exist, and to adapt to the new behaviours and desires of our post-modern society, i.e., the tendency to refocus on essential values, such as conviviality, sociability, hospitality and cultural enrichment. Tunisian villages have a great heritage that could contribute to this tourism experience and create unique experiences for tourists while generating revenue for the community. It is therefore in their interest to use promotional campaigns to highlight the capacity of the tourism offering—for example, culinary, sporting or cultural activities—to create circumstances that are conducive to bringing people together, interacting and sharing (

Marchat, 2019).

Similarly, certain tourist services can be designed with the aim of encouraging this dimension of socio-cultural practice: we are thinking of group leisure activities or segmentation during transport and accommodation, according to the desired level of interaction with others (

Marchat, 2019). Tourism managers can develop and promote activities that are in line with this (culinary workshops on local products, making “typical” objects, etc.). In addition, traditional tourism managers could become more competitive by working on the intrapersonal and interpersonal skills of their contact staff in order to provide their customers with social experience. To stand out from the crowd, they need to propose offers that give consumers the impression of being immersed in the culture they are visiting and thus enjoying an original experience that goes beyond the simple act of consumption. For example, it would be interesting to offer a number of cultural events organised regularly in the group’s hotels, clubs and communal areas to encourage socialisation, incorporating elements designed to promote social integration, such as local activities, day trips, themed evenings, etc. The aim is to design tourist services that reflect the values of couchsurfers.

As well as the social aspect, the economic aspect must also be taken into account by hotel managers, as today’s consumers are looking for the best value for money. Access to the Internet means that new travellers can constantly compare prices on comparison sites or find the best deals on forums or last-minute sites. The traditional hotel industry must therefore offer a human experience at an affordable price.

7. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Avenues of Research

This study aimed at developing a reliable and valid measurement scale for examining perceived value by couchsurfers. The study started by reviewing the related literature and two main phases of primary data collection using Churchill’s paradigm. The first phase included an interview with 26 European couchsurfers to identify the main themes and perceived values. The results of the first phase informed the second phase including two steps: step 1 included the administration of a questionnaire to a sample of 102 couchsurfers to assess the 68 items collected from phase one. The results of this step showed the three main values of the couchsurfing experience. These were economic, exploration and socio-cultural. Step 2 included a questionnaire directed to a sample of 243 Europeans. The results showed a reliable and valid scale with three main values: economic, exploration and socio-cultural. Each value had three factors. This scale will help policymakers and service providers better understand the experience of couchsurfers. This contributes to tourism development overall, including rural development.

As with all research, there are limitations to this study, some of which could be explored in future work. Firstly, our sample was limited to couchsurfers, so it would be interesting to work on the perceived values of hosts in welcoming strangers and providing a service. It would also be interesting to test the effect of the perceived value of couchsurfing on satisfaction with the stay and its effect on the intention to repeat the experience. It would be interesting to examine the economic impact of this tourism experience on rural development within the case of Tunisa or other similar countries.

Author Contributions

All authors had equal participation in the research. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, grant number KFU250869. This research was funded by the General Directorate of Scientific Research & Innovation, Dar Al Uloom University, through the Scientific Publishing Funding Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Deanship of Scientific Research Ethical Committee, King Faisal University (project number: KFU250869, date of approval: 1 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data from the interviews can be shared with researchers who meet the eligibility criteria after consent from the KFU Ethical Committee.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Interview Guide

Hi, first I would like to thank you for taking part in this study. The subject is the phenomenon of couchsurfing as a new form of tourism. Before we start, I would like to inform you that this interview is strictly confidential and that the data collected will be used for scientific research purposes only. Finally, there are no right or wrong answers; you can answer according to your own experience.

- -

How do you organise your holidays in general?

- -

Can you tell me why you chose couchsurfing?

- -

Overall, can you tell me about your couchsurfing experience?

- -

What benefits did you gain from your couchsurfing experience?

- -

Relaunch: And again? Could you comment on each of the benefits you have just mentioned?

- -

If you had to bring back one memory from couchsurfing, what would it be?

- -

What did this experience bring to you as a way of travelling?

- -

Do you have anything to add?

If you are interested, I will send you the results of the study very shortly. Thanks again, and see you soon.

References

- Amirou, R. (2008). Les communautés de consommateurs comme espace transitionnel: Le cas du tourisme. Décisions Marketing, 4, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, T. D. Q. (2023, November 3–4). Shareable tourism and beyond: Understanding the determinants of continued hosting on couchsurfing. 11th International Conference on Emerging Challenges: Smart Business and Digital Economy 2023 (ICECH 2023) (pp. 547–554), Ninh Binh, Vietnam. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnefoy-Claudet, L. (2011). Les effets de la thématisation du lieu sur l’expérience vécue par le consommateur: Une double approche cognitive et expérientielle [Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Grenoble]. [Google Scholar]

- Bourliataux-Lajoinie, S., & Rivière, A. (2013). L’enjeu des m-services en marketing touristique territorial: Proposition d’un cadre d’analyse. Recherches en Sciences de Gestion, 2, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A., & Cramer, D. (2012). Quantitative data analysis with IBM SPSS 17, 18 & 19: A guide for social scientists. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, A., Shi, F., & Bai, B. (2022). A comparative review of hospitality and tourism innovation research in academic and trade journals. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(10), 3790–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. J. (2018). Couchsurfing: Performing the travel style through hospitality exchange. Tourist Studies, 18(1), 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E., & Stasiak, J. (2023). Domestic tourism preferences of Polish tourist services’ market in light of contemporary socio-economic challenges. In The international conference on strategic innovative marketing and tourism (pp. 479–487). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G. (1979). A better paradigm for Developing Measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consalter, L. (2024). Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence: The Case of Couchsurfing.com [Master’s Thesis, Linköping University]. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384933712_Technology-Facilitated_Gender-Based_Violence_The_Case_of_Couchsurfingcom (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Coquin, S. (2008). La longue marche vers le tourisme participatif. Espaces, 264, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Couchsurfing.com. (2025). Available online: https://www.semrush.com/website/couchsurfing.com/overview/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Decrop, A., & Degroote, L. (2014). Le Couchsurfing. Un réseau d’hospitalité entre opportunisme et idéalisme. Revue de Recherche en Tourisme, 33(33), 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Evrard, Y., Pras, B., & Roux, E. (2000). Market: Etudes et recherche sen marketing, avec la collaboration de Choffray JM. Dussaix AM et Claessens M. Dunod. [Google Scholar]

- Filser, M., & Plichon, V. (2004). La valeur du comportement de magasinage. Statut théorique et apports au positionnement de l’enseigne. Revue Française de Gestion, 1(148), 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, H. (2004). Le tourisme durable une organisation du tourisme en milieu rural. Revue D’économie Régionale & Urbaine, 1, 57–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gallarza, M. G., & Saura, I. G. (2006). Value dimensions, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: An investigation of university students’ travel behavior. Tourism Management, 27(3), 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. R., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (2014). Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig, K., Felicitas, M., & Bruno, K. (2014). Sharing as a staged performance. An analysis of the hospitality platform Couchsurfing as a socio-romantic sharing utopia. HEC Lausanne. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M. B. (1994). The nature of customer value: An axiology of services in the consumption experience. In R. T. Rust, & R. L. Oliver (Eds.), Service quality: Newdirections in theory and practice (pp. 21–71). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M. B. (1999). Consumer value: A framework for analysis and research. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M. B. (2009). The conceptualization and measurement of consumer value in services. International Journal of Market Research, 45, 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X., Cui, Q., & Chen, Z. (2023). Couchsurfing in China: Guanxi networks and trust building. Tourist Studies, 23(1), 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igalens, J., & Roussel, P. (1998). From research methods in human resource management. Economica. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrier, E., Bourgeon-Renault, D., & Belvaux, B. (2019). Une mesure des effets de l’utilisation d’un outil numérique sur l’expérience de visite muséale. Management & Avenir, 108(2), 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog, K. G. (1988). Analysis of Covariance Structures. In R. B. Cattell (Ed.), The handbook of multivariate experimental psychology (pp. 207–230). Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. (2012). The intimate stranger on your couch: An analysis of motivation, presentation and trust through couchsurfing. Uppsala University. [Google Scholar]

- Marchat, J. F. (2019). Sociologues au CRIDA. Connexions, 111(1), 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwick, C., Malhotra, N. K., & Rigdon, E. (2001). Experiential value: Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and internet shopping environment. Journal of Retailing, 77, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos-Wasem, R. (2004). Le tourisme lent contre le bruit et la fureur des vacances. La Revue Durable, 11, 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Pedhazur, E. J., & Schmelkin, L. P. (1991). Measurement design, and analysis, an integrated approach. Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Priskin, J., & Sprakel, J. (2008). “Couchsurfing”: À la recherche d’une expérience touristique authentique. Téoros, 27(1), 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, A., Rehman, M. A., Sharif, S., & Lodhi, R. N. (2023). The role of social media marketing and social support in developing value co-creation intentions: A Couchsurfing community perspective. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchi, J., Lewis, L., Nicholls, C., & et Ormston, R. (2013). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (456p). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Roussel, P. (2005). Ladders Development methods for survey questionnaires. In P. Roussel, & F. Wacheux (Eds.), Human resource management: Social science research methods. De Boeck. [Google Scholar]

- Roussel, P., Durrieu, F., Campoy, E., & Akremi, A. (2005). Analyse des effets linéaires par modèles d’équations structurelles. Dans Management des Ressources Humaines, 11, 297–324. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, D. (2011). The sharing economy. Fast Company, 155, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchèz, J., Callarisa, L., Rodriguez, R. M., & Moliner, M. A. (2006). Perceived value of the purchase of a tourism product. Tourism Management, 27(3), 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G., Mota, V. F., Benevenuto, F., & Silva, T. H. (2020). Neutrality may matter: Sentiment analysis in reviews of Airbnb, Booking, and Couchsurfing in Brazil and USA. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEATM (Service d’Études et d’Aménagement Touristique de la Montagne). (2000). Quatrième partie: « Un plan d’action pour le tourisme en “moyenne montagne” », Contribution du tourisme au développement durable de la montagne, 200 ko, 36 pages. Available online: https://www.vie-publique.fr/files/rapport/pdf/014000281.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Vera, L. A. R., de Sevilha Gosling, M., Silva, J. A., & de Freitas Coelho, M. (2024). Alternative Tourism and Shared Accommodation Motivation: A cross-national study. Almatourism, Journal of Tourism, Culture and Territorial Development, 14(25), 107–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. (2024). How Platform Exchange and Safeguards Matter: The Case of Sexual Risk in Airbnb and Couchsurfing. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 8(CSCW1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P., & Soutar, G. N. (2009). Value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions in an adventure tourism context. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(3), 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, T. (2015). The study of online hospitality exchange: The case of couch surfing network. University of Applied Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price quality and value: A means-end model synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgolli, S., & Zaiem, I. (2018). Couchsurfing: A new form of sustainable tourism and an exploratory study of its motivations and its effect on satisfaction with the stay. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 12(1), 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).