Gender Gaps, Financial Inclusion and Social Integration in Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Refugee Situation in Context

2.2. Study Context

2.3. Theoretical Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Measuring Financial Inclusion and Social Integration

3.3. Models of Financial Inclusion and Social Integration

3.4. Analysing the Gender Gaps in Financial Inclusion and Social Integration

4. Results

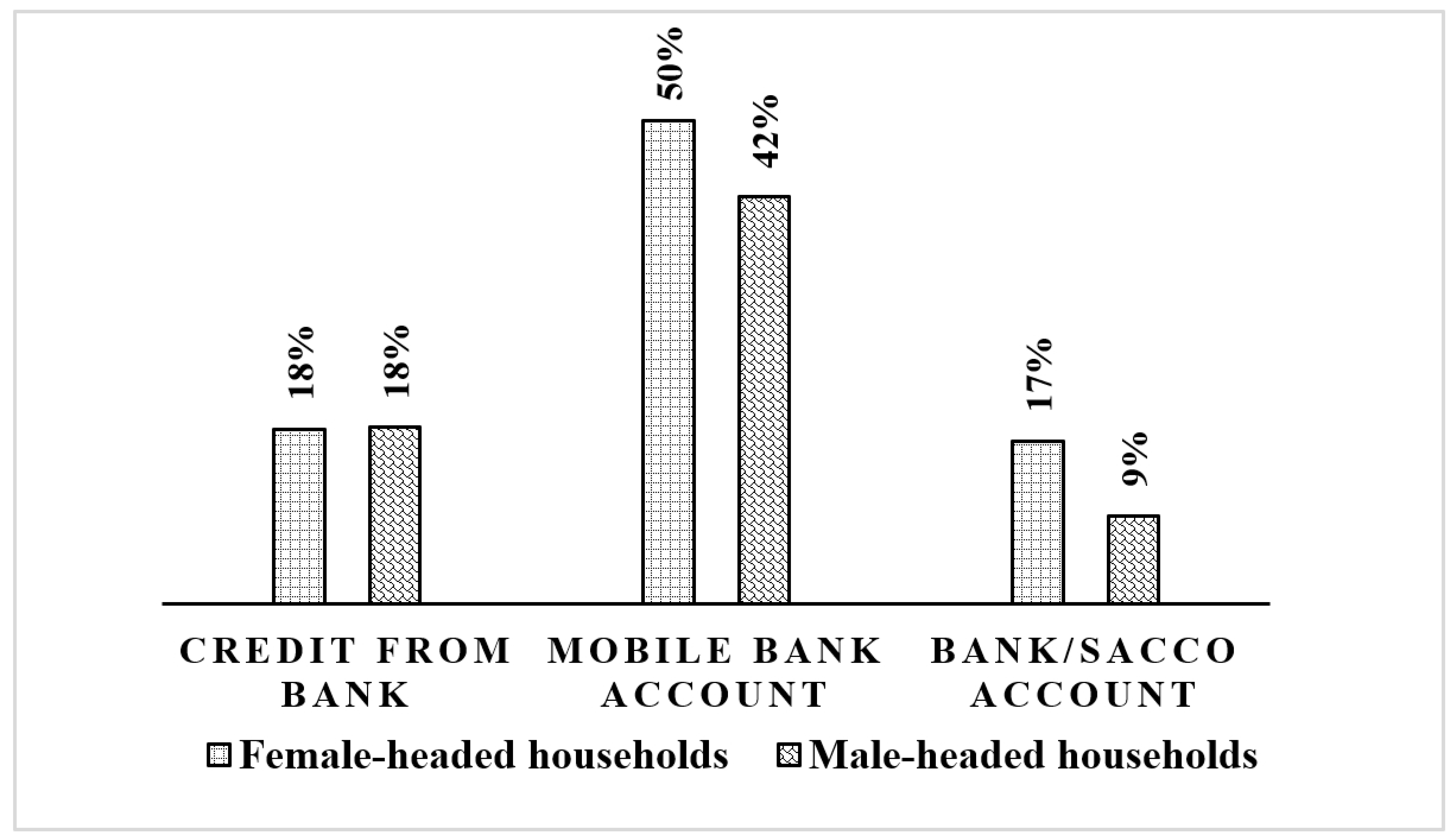

4.1. Social and Economic Profiles of Male and Female-Headed Households in Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya

4.2. Drivers of Financial Inclusion Among Female and Male-Headed Households

4.3. Drivers of Social Integration Among Female and Male-Headed Households

4.4. Estimation of the Gender Gap in Financial Inclusion

4.5. Estimation of the Gender Gap in Social Integration

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Household size (ln) | 1.35 | 0.742359 |

| Age of the household head (ln) | 1.48 | 0.676163 |

| Access to information (yes) | 1.03 | 0.971774 |

| Earned wages (yes) | 1.11 | 0.899302 |

| Married (yes) | 1.05 | 0.951096 |

| Friends/relatives resettled abroad (yes) | 1.11 | 0.899163 |

| Education expenditure (Ksh., ln) | 1.23 | 0.813376 |

| Asset index | 1.27 | 0.78731 |

| Food vulnerability | ||

| 50th quantile | 1.37 | 0.730686 |

| 75th quantile | 1.45 | 0.688415 |

| Interaction with neighbors (yes) | 1.03 | 0.971156 |

| Dependency ratio (ln) | 1.16 | 0.858378 |

| English literacy (yes) | 1.48 | 0.674891 |

| Mean VIF | 1.24 | - |

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Household size (ln) | 1.35 | 0.742097 |

| Age of household head (ln) | 1.47 | 0.681523 |

| Access to information (yes) | 1.04 | 0.964652 |

| Earned wages (yes) | 1.11 | 0.901216 |

| Married (yes) | 1.05 | 0.956099 |

| Friends/relatives resettled abroad (yes) | 1.1 | 0.91186 |

| Education expenditure (log) | 1.25 | 0.801129 |

| Dependency ratio (ln) | 1.17 | 0.854283 |

| English literacy (yes) | 1.49 | 0.673347 |

| Financial inclusion | 1.17 | 0.851299 |

| Own smartphone (yes) | 1.18 | 0.845742 |

| Food vulnerability | ||

| 50th quantile | 1.38 | 0.72658 |

| 75th quantile | 1.45 | 0.691652 |

| Mean VIF | 1.25 | - |

| 1 | The exchange rate: 1 United States Dollar (USD) = 129.3 Kenya Shilling (KES) in August 2024. |

References

- Alinovi, L., Mane, E., & Romano, D. (2009). Measuring household resilience to food insecurity: An application to palestinian households. In R. Benedetti, F. Piersimoni, M. Bee, & G. Espa (Eds.), Agricultural survey methods (pp. 557–582). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, F., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., & Peria, M. S. M. (2016). The foundations of financial inclusion: Understanding ownership and use of formal accounts. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anarfo, E. B., Amewu, G., & Dzeha, G. C. (2020). Financial inclusion and migrant remittances in sub-Saharan Africa: A panel VAR approach. International Journal of Social Economics, 47, 809–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, A. (2022). Impact of financial inclusion on food security: Evidence from developing countries. International Journal of Social Economics, 49, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, A., Bloom, L., & Omata, N. (2022). Refugee economies: Forced displacement and development. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, A., Geervliet, R., MacPherson, C., Omata, N., Rodgers, C., & Sterck, O. (2018). Self-reliance in Kalobeyei? Socio-economic outcomes for refugees in North-West Kenya. Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat, A. (2020). Experimental financial inclusion as refugee management: Shelter insecurities at the bottom of the pyramid in Kenya. International Journal of Housing Policy, 21, 484–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S., & Singh, S. (2019). Empowering women through financial inclusion: A study of urban slum. Vikalpa, 44, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder, A. S. (1973). Wage discrimination: Reduced form and structural estimates. Journal of Human Resources, 8, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemraad, I., Esses, V. M., Kymlicka, W., & Zhou, Y. Y. (2023). Unpacking immigrant integration: Concepts, mechanisms, and context. World Development Report. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas, G. J. (2019). Immigration and economic growth. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper 25836. [Google Scholar]

- Daneshvar, C., Garry, S., López, J., Santamaría, J., & Villarreal, F. G. (2017). Financial inclusion of small-scale rural producers: Trends and challenges. United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan, S. M., Wilson, K., & Zademach, H.-M. (2024). From financial inclusion to financial health of refugees: Urging for a shift in perspective. Third World Quarterly, 45, 926–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J. (2016). Social capital (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion (GPFI). (2020). G20 2020 financial inclusion action plan. Available online: https://www.gpfi.org/publications (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Government of Kenya. (2021). The Kenya poverty report based on the 2021 Kenya continuous household survey. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Kenya. (2023). Third county integrated development plan: 2023–2027. Turkana County Government. [Google Scholar]

- Gujarati, D. N. (2015). Econometrics by example (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, R. R., El-Harakeh, A., Ziadee, M., Younes, E. A., & El Asmar, K. (2020). Social capital, social cohesion, and health of Syrian refugee working children living in informal tented settlements in Lebanon: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Medicine, 17, e1003283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K., & Bushell, H. (2013). A multidimensional approach for measuring resilience. Working paper. Oxfam GB. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). (2018). Kakuma as a marketplace: A consumer and market study of a refugee camp and town in Northwest Kenya. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Jann, B. (2008). The blinder–oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. The Stata Journal, 8, 453–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenson, J. (2010). Defining and measuring social cohesion. No. 1. Commonwealth Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., & Liu, Y. (2022). Does financial inclusion help alleviate household poverty and vulnerability in China? PLoS ONE, 17, e0275577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, G., Pesqué-Cela, V., Tian, L., & Luo, D. (2020). A theory of financial inclusion and income inequality. The European Journal of Finance, 28(1), 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, I., Koomson, P., & Abdul-Mumuni, A. (2023). Trust in banks, financial inclusion and the mediating role of borrower discouragement. International Review of Economics and Finance, 88, 1418–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, I., Villano, R. A., & Hadley, D. (2020). Effect of financial inclusion on poverty and vulnerability to poverty: Evidence using a multidimensional measure of financial inclusion. Social Indicators Research, 149, 613–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, U. (2021). Difficult life in a refugee camp: Gender, violence, and coping in Uganda. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux, B., & Rouanet, H. (2010). Multiple correspondence analysis (Vol. 163). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Link, A.-C., Zhu, Y., & Karutz, R. (2021). Quantification of resilience considering different migration biographies: A case study of Pune, India. Land, 10, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loaba, S. (2023). Gender-related differences in access to financial accounts in sub-Saharan Africa. International Economic Journal, 37, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martey, E. (2022). Blessing or burden: The elderly and household welfare in Ghana. Social Indicators Research, 162, 803–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A. S. (2014). Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 1, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendola, D., & Pera, A. (2021). Vulnerability of refugees: Some reflections on definitions and measurement practices. International Migration, 5, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, H. (2020). Access to finance—Mind the gender gap. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 78, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muricho, D. N., Otieno, D. J., Oluoch-Kosura, W., & Jirström, M. (2019). Building pastoralists’ resilience to shocks for sustainable disaster risk mitigation: Lessons from West Pokot County, Kenya. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 34, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseh, M., Lee, J., Zeng, Y., Nabunya, P., Alvarez, V., & Safi, M. (2024). Understanding economic integration in immigrant and refugee populations: A scoping review of concepts and metrics in the United States. Economies, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njanike, K., & Mpofu, R. T. (2024). Factors influencing financial inclusion for social inclusion in selected African countries. Insight on Africa, 16, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsabimana, A., Swain, R. B., Surry, Y., & Ngabitsinze, J. C. (2020). Income and food engel curves in Rwanda: A household microdata analysis. Agricultural and Food Economics, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oaxaca, R. (1973). Male-Female Wage Differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review, 14, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello, A. O., Nzuma, J. M., Otieno, D. J., Kidoido, M., & Tanga, C. M. (2021). Farmers’ perceptions of commercial insect-based feed for sustainable livestock production in Kenya. Sustainability, 13(10), 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. (2021). Financial inclusion research around the world: A review. Forum for Social Economics, 50(4), 457–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, R. K. (2021). Involuntary dislocation: Home, trauma, resilience, and adversity-activated development. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J., Lee, S., & Park, J. (2024). The economic decision of international migration: Two empirical evidences from the United States and Canada. Economies, 12, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrich, A. C. G., Vieira, K. M., & Kirch, G. (2015). Determinants of financial literacy: Analysis of the influence of socioeconomic and demographic variables. Revista Contabilidade and Finanças, 26, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayitno, G., Dinanti, D., Efendi, A., Hayat, A., & Dewi, P. P. (2022). Social capital of Pujon Kidul communities in supporting the development of the COVID-19 resilience village. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 17, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. (2001). Social capital: Measurement and consequences. Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. (2006). Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarma, M. (2008). Index of financial inclusion. Working paper. Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Swamy, V. (2014). Financial inclusion, gender dimension, and economic impact on poor households. World Development, 56, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. (2018). Global compact on refugees indicator report. UNHCR. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. (2022). The global compact on refugees: Progress report. UNHCR. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. (2023). Global report: East and Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes. UNHCR. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. (2024a). Data-driven support for refugee resilience in East, Horn and Great Lakes of Africa. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/blogs/data-driven-support-for-refugee-self-reliance-in-east-horn-and-great-lakes-of-africa/ (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- UNHCR. (2024b). Global population planning figures. Global Appeal. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. (2024c). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2023. UNHCR. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. (2024d). Kenya registered refugees and asylum seekers as of June 30, 2024. Kenya statistics package. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/ke/what-we-do/reports-and-publications/kenya-operation-statistics (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- UNHCR & World Bank. (2019a). Socioeconomic survey of refugees in Kakuma. UNHCR Microdata Library. Available online: https://microdata.unhcr.org/index.php/catalog/302 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- UNHCR & World Bank. (2019b). Understanding the socioeconomic conditions of refugees in Kenya (Vol. A). Kalobeyei Settlement. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR & World Bank. (2021). Understanding the socioeconomic differences of urban and camp-based refugees in Kenya. Comparative Analysis Brief. [Google Scholar]

- Valentova, M. (2016). How do traditional gender roles relate to social cohesion? Focus on differences between women and men. Social Indicators Research, 127, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Horn, A., Weitz, C. A., Olszowy, K. M., Dancause, K. N., Sun, C., Pomer, A., Silverman, H., Lee, G., Tarivonda, L., Chan, C. W., Kaneko, A., Lum, J. K., & Garruto, R. M. (2019). Using multiple correspondence analysis to identify behaviour patterns associated with overweight and obesity in vanuatu adults. Public Health Nutrition, 22, 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellalage, N. H., & Locke, S. (2020). Remittance and financial inclusion in refugee migrants: Inverse probability of treatment weighting using the propensity score. Applied Economics, 52, 929–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessendorf, S., & Phillimore, J. (2019). New migrants’ social integration, embedding and emplacement in superdiverse contexts. Sociology, 53, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wither, D., Orchiston, C., & Nel, E. (2023). Using the living standards framework to analyse the drivers of social resilience in a disaster management context. Policy Quarterly, 19, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, M. (2001). The place of social capital in understanding social and economic outcomes. Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2021). Refugee policy review framework. Technical note. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

| Social Integration Indicators | Female-Headed Households (N = 1094) | Male-Headed Households (N = 735) | Pooled (N = 1829) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Do you feel that people in this neighborhood are trustworthy? | 4.15 (1.13) | 4.16 (1.12) | 4.15 (1.12) |

| 2. | Do you feel that most people in the host community are trustworthy? | 3.26 (1.28) | 3.37 (1.30) | 3.31 (1.29) |

| 3. | Would you feel safe if you went to Kakuma town by yourself? | 3.80 (1.12) | 3.81 (1.19) | 3.80 (1.15) |

| 4. | Would you feel comfortable if your child or grandchild were to socialize or be friends with children of host community people? | 3.10 (1.33) | 3.17 (1.34) | 3.13 (1.33) |

| 5. | Do you feel safe walking alone in your area/neighborhood during the day? | 4.35 (0.80) | 4.33 (0.89) | 4.34 (0.86) |

| 6. | Do you feel safe walking alone in your area/neighborhood at night? | 2.11 (1.11) | 2.19 (1.17) | 2.14 (1.14) |

| 7. | Do you feel that you are able to express your opinion through the existing community leadership structure? | 3.55 (1.16) | 3.59 (1.18) | 3.57 (1.17) |

| 8. | Do you feel like your opinion is being considered for decisions that affect your well-being? | 3.18 (1.18) | 3.29 (1.24) | 3.23 (1.21) |

| 9. | How much would you say the political system in Kenya allows people like you to have a say in what the government does? | 2.43 (1.37) | 2.53 (1.40) | 2.47 (1.38) |

| Female-Headed Households (N = 1094, 59.81%) | Male-Headed Households (N = 735, 40.19%) | Pooled (N = 1829) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household head characteristics | Mean or % | Mean or % | Mean or % | Difference in means by gender |

| Dependent variables | ||||

| Financial inclusion index | 0.08 (0.03) | −0.12 (0.04) | 6.55 × 10−9 (1.00) | −4.28 *** |

| Social integration index | −0.35 (2.26) | 0.22 (3.89) | −0.12 (3.03) | 3.91 *** |

| Explanatory variables | ||||

| Average age in years | 37.15 (11.11) | 33.39 (11.28) | 35.60 (11.33) | −7.2149 *** |

| Age groups: <18 years 18–60 years >60 years | 1.46 95.16 3.38 | 3.40 95.37 1.22 | 2.24 95.24 2.52 | 15.5119 *** |

| Average household size | 7.68 (3.70) | 5.85 (4.14) | 6.94 (3.99) | −9.8410 *** |

| Dependency ratio | 1.46 (1.32) | 0.83 (0.94) | 1.21 (1.22) | −11.1954 *** |

| Married (% yes) | 23.77 | 6.26 | 16.73 | 96.72 *** |

| Attended school in Kenya (% yes) | 41.77 | 81.63 | 57.79 | 286.34 *** |

| Highest education attained (% Secondary and above) | 28.24 | 47.76 | 36.09 | 72.56 *** |

| Average education expenditure in KES. | 6324.71 (12,178) | 6443 (10,056.73) | 6367.11 (11,463.95) | 0.1833 |

| Earned wages (% yes) | 17.82 | 36.19 | 25.21 | 78.66 *** |

| Average number of economic activities | 0.4 (0.82) | 0.66 (0.97) | 0.5 (0.89) | −6.08 *** |

| Access to needed information (% yes) | 54.48 | 54.56 | 54.51 | 0.0011 |

| Willing to leave Kenya (% yes) | 82.45 | 83.54 | 82.89 | 0.35 |

| Possession of Refugee ID (% yes) | 61.52 | 54.29 | 58.61 | 9.48 *** |

| Asset accumulation index | −0.33 (1.65) | 0.12 (2.04) | 0 (1) | 5.11 *** |

| Friends/relatives resettled abroad (% yes) | 16.36 | 22.31 | 18.75 | 10.2283 *** |

| Interaction with neighbors outside the camp | 54.02 | 49.52 | 52.21 | 3.5651 * |

| Female-Headed Households | Male-Headed Households | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Odds Ratio | ρ-Value | Odds Ratio | ρ-Value |

| Household size (ln) | 0.786 (0.101) | 0.060 | 0.898 (0.109) | 0.375 |

| Age of the household head (ln) | 0.943 (0.233) | 0.811 | 0.575 ** (0.162) | 0.050 |

| Access to information (yes) | 1.558 *** (0.203) | 0.001 | 1.760 *** (0.283) | 0.000 |

| Earned wages (yes) | 0.489 *** (0.086) | 0.000 | 0.422 *** (0.075) | 0.000 |

| Married (yes) | 1.180 (0.184) | 0.287 | 0.772 (0.272) | 0.462 |

| Friends/relatives resettled abroad (yes) | 0.404 *** (0.075) | 0.000 | 0.464 *** (0.099) | 0.000 |

| Education expenditure (KES., ln) | 0.885 ** (0.045) | 0.017 | 0.871 ** (0.061) | 0.048 |

| Asset index | 1.774 *** (0.148) | 0.000 | 1.372 *** (0.115) | 0.000 |

| Food vulnerability | ||||

| 50th quantile | 1.567 *** (0.239) | 0.003 | 1.667 ** (0.347) | 0.014 |

| 75th quantile | 2.114 *** (0.350) | 0.000 | 2.307 *** (0.466) | 0.000 |

| Interaction with neighbors (yes) | 0.669 *** (0.087) | 0.002 | 0.620 *** (0.099) | 0.003 |

| Dependency ratio (ln) | 1.023(0.054) | 0.662 | 1.151 (0.128) | 0.208 |

| English literacy (yes) | 0.990 (0.173) | 0.954 | 0.620 *** (0.115) | 0.010 |

| /Cut 1 | −1.216 (1.102) | −3.571 (1.189) | ||

| /Cut 2 | −0.934 (1.102) | −3.259 (1.188) | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1096 *** | 0.1165 *** | ||

| Observations | 1094 | 735 |

| Female-Headed Households | Male-Headed Households | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Odds Ratio | ρ-Value | Odds Ratio | ρ-Value |

| Household size (ln) | 1.548 *** (0.183) | 0.000 | 1.260 ** (0.137) | 0.034 |

| Age of household head (ln) | 1.319 (0.300) | 0.224 | 3.196 *** (0.834) | 0.000 |

| Access to information (yes) | 1.170 (0.141) | 0.194 | 1.133 (0.169) | 0.403 |

| Earned wages (yes) | 1.280 (0.202) | 0.117 | 1.431 ** (0.235) | 0.030 |

| Married (yes) | 1.329 (0.187) | 0.043 | 1.666 (0.529) | 0.108 |

| Friends/relatives resettled abroad (yes) | 2.275 *** (0.374) | 0.000 | 1.620 *** (0.300) | 0.009 |

| Education expenditure (KES, ln) | 0.979 (0.046) | 0.648 | 0.957 (0.062) | 0.499 |

| Dependency ratio (ln) | 0.880 ** (0.044) | 0.011 | 1.041 (0.106) | 0.694 |

| English literacy (yes) | 0.993 (0.574) | 0.964 | 1.012 (0.177) | 0.946 |

| Financial inclusion | 0.791 *** (0.053) | 0.000 | 0.762 *** (0.060) | 0.001 |

| Own smartphone (yes) | 3.139 *** (0.405) | 0.000 | 3.734 *** (0.599) | 0.000 |

| Food vulnerability | ||||

| 50th quantile | 1.173 (0.168) | 0.266 | 1.107 (0.213) | 0.599 |

| 75th quantile | 1.378 *** (0.208) | 0.033 | 1.386 * (0.258) | 0.080 |

| /Cut 1 | 2.054 (1.006) | 4.788 (1.094) | ||

| /Cut 2 | 3.708 (1.011) | 6.212 (1.104) | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1043 | 0.1354 | ||

| Observations | 1094 | 735 |

| Mean Gender Differential | Coefficients |

|---|---|

| Mean male-headed household financial inclusion | 2.10 *** (0.04) |

| Mean female-headed household financial inclusion | 2.29 *** (0.03) |

| Mean gender gap in financial inclusion | −0.19 *** (0.05) |

| Endowment effect | −0.07 ** (0.03) |

| Coefficient effect | −0.15 *** (0.06) |

| Interaction effect | 0.03 (0.05) |

| Mean Gender Differential | Coefficients |

|---|---|

| Mean male-headed household social integration | 1.097 *** (0.011) |

| Mean female-headed household social integration | 1.092 *** (0.008) |

| Mean gender gap in social integration | 0.005 (0.014) |

| Endowment effect | 0.021 ** (0.008) |

| Coefficient effect | −0.004 (0.016) |

| Interaction effect | 0.011 (0.013) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okello, A.O. Gender Gaps, Financial Inclusion and Social Integration in Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya. Economies 2025, 13, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13030075

Okello AO. Gender Gaps, Financial Inclusion and Social Integration in Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya. Economies. 2025; 13(3):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13030075

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkello, Afrika Onguko. 2025. "Gender Gaps, Financial Inclusion and Social Integration in Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya" Economies 13, no. 3: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13030075

APA StyleOkello, A. O. (2025). Gender Gaps, Financial Inclusion and Social Integration in Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya. Economies, 13(3), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13030075