This section presents the econometric results. First is the impact of the level of education on the economic empowerment of women, then the results of the impact of economic empowerment of mothers on child mortality.

4.1. Level of Education and the Economic Empowerment of Women

This section examines the impact of the level of education of women on their economic empowerment. Nevertheless, for testing robustness, we also focused on the impact of the number of years spent in school and access to literacy by women on their level of economic empowerment.

Table 3 presents the results of an analysis of the impact of the level of education of women on the probability of their economic empowerment.

The results of the estimation of the two-stage least squares (2SLS) demonstrated that the level of education (primary) variable has a negative but insignificant impact on the various indicators of economic empowerment, namely participation by women in income generation, and their decision-making power in terms of the use of their own income and family expenditure. One possible explanation for why the primary school level of education variable lacks significance in regard to the economic empowerment of women could be the low income yields from primary school level education (

Cameron et al., 2001). Furthermore, when the level of education of the woman increases to that of secondary school it reduces her economic independence, notably in regard to contributing to household income. For example, when the level of education of the woman increases from primary to secondary level, income decreases by 0.92%. It is evident that the secondary school level of education has a negative impact on women’s participation in contributing to household income and that the impact becomes significant with its improvement. Such a result is contrary to the economic theory on human capital (

Schultz, 1960;

Becker, 1964), which highlights the significant role played by education on economic growth and development. It is also contrary to the results of several empirical studies (see, for example,

Bussemakers et al., 2017;

Dhanaraj & Mahambare, 2019). However, the result agrees with the results of various researchers (

Ahmed & Hyndman-Rizk, 2018;

Assaad et al., 2020). This result could be due to the low participation of graduates in the labour market due to structural problems in Burkina Faso’s economy, the mismatch between the economic fabric of society and the knowledge acquired through traditional education. Indeed, in Burkina Faso the dominant education system offers general education which does not create enough possibilities for the private sector in regard to the employment of educated women. This leads to a decrease in employment opportunities in the public sector which is seen as the main provider of jobs, resulting in a diminishing of the participation of educated women in the labour market. In addition, this result can be explained by the fact that despite women’s level of education, they still encounter substantial obstacles in transforming their education into meaningful empowerment (

Rana et al., 2024). These problems include restricted freedom and mobility, cultural and societal expectations, family obligations, economic factors, etc.

Further to the level of education, other factors influence the economic empowerment of women, such as the area of residence of the household and the level of education of the spouse. When the level of education of the spouse is above primary of secondary school, it leads to an improvement in the income of their partner which increases from 4.9% to 6.2%. Equally, the decision-making power of the partner increases in the same manner. One of the possible explanations for this result is that women with partners of a certain level of education have more freedom to enjoy their rights than those whose partners have a minimum level of education. This is because the existing literature on women’s rights could be unknown to partners who are illiterate.

Moreover, living in rural areas reduces women’s chances of increasing their income and decision-making power over the management of the income by 19.78% and 4.8% respectively. These results could be explained through the fact that due to socio-cultural burdens, the role of the woman in Burkina Faso is still traditional in rural areas, as compared to the urban areas. The woman’s role is to take care of the needs of family members (among other domestic duties) that do not include the financial needs of the household. Also, rural areas offer fewer employment opportunities than urban areas.

Marital status also has an impact on the empowerment of women. In our study, women with a partner experienced a reduction in their probability of pay out, management power over their income and participation in family responsibilities by 8%, 3% and 2.2%, respectively. These results could be because the family obligations for women with partners are a hindrance to job seeking and income-generating activities. Similarly, it could be justified through the fact that women with a partner could choose to share those responsibilities with that person, whereas single women do not have a choice and have to do everything on their own. In regard to religion, the results highlighted the fact that women in Christian households have better opportunities for improving their participation in household responsibilities. This is probably because contrary to Christianity, Islam could limit access by women to various income-generating activities that could be proscribed by Islamic law, for example. This limits access by such women to resources that could help them become economically empowered.

In order to verify the results of the level of education on the economic empowerment of women, we examined the various indicators of education, namely the number of years spent in school and the literacy level.

Table 4 presents the results of an analysis of the impact of the number of years spent in school on the economic empowerment of women in Burkina Faso.

The results of the estimation using the 2SLS method, as illustrated in

Table 4, indicate that the number of years spent in school has a negative impact on the participation of the woman in contributing to income. However, it is evident that there is a positive impact of the number of years spent in school on decision making in regard to household expenditure. Nevertheless, the negative impact related to the participation of the women in contributing to family income is higher in absolute value than the positive impact resulting from her participation in decision making. Consequently, the more the years spent in school, the more the economic empowerment of the woman increases. This therefore confirms the fact that the level of education promotes the economic empowerment of women.

Table 5 presents the results of an analysis of the impact of literacy on the economic empowerment of women.

The results in

Table 5 suggest that access to literacy programmes promotes the economic empowerment of women, notably through an improvement in the participation of women in terms of contributing to an improvement in household income and in decision making in regard to family expenditure. This result not only agrees with the economic theory of human capital (

Schultz, 1990;

Becker et al., 1994) but also with results from previous empirical studies (

Oyitso & Olomukoro, 2012;

Adelore & Olomukoro, 2015). One of their underlying arguments is that literacy programmes allow women who benefit from them to access more income-generating activities than those that do not benefit from them. In addition, this result differs from that of the impact of the number of years spent in school on the economic empowerment of women highlighted previously. This could be explained through the fact that contrary to the traditional system of education in which general education is emphasized, the strategies that literacy programmes implement are accompanied by specific vocational training made possible by setting up literacy and training centres.

In summary, in Burkina Faso, the level of education and the number of years spent in school do not improve the economic empowerment of women. However, literacy programmes for women have contributed to increasing their economic empowerment. This can be explained by the fact that the transmission of education for women’s economic empowerment requires quality education (

Almugren et al., 2024). Consequently, we can state that although the level of education of the women is necessary in order to improve their human capital, it is not enough to ensure their empowerment.

4.2. Economic Empowerment of Women and Child Mortality

In this section, we propose an examination of the impact of economic empowerment on three main indicators of child mortality. To that effect, various results are given in

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8, through an examination of the mortality of children below one year of age (infant mortality), the mortality of children below one month of age (neonatal mortality) and the mortality of children aged below five years (infant child mortality) respectively as outcome variables. From various estimations, we used the education variable as an instrument.

Overall, the results indicate that the economic empowerment of women seems to have a negative impact on the probability of the death of children. Indeed, when one considers the number of children as an instrument, then the participation of the mother in decision making in regard to family expenditure contributes to a decrease in child mortality in Burkina Faso. For example, the coefficient associated with the variable of participation by the woman in decision making on family expenditure was negative. More specifically, an increase in participation by the wife in decision making in regard to family expenditure was negative. These results are contrary to those arrived at in previous studies such as those in Indonesia (

Titaley et al., 2008), Bangladesh (

Hossain, 2015) and Sierra Leone (

Cornish et al., 2019). However, economic empowerment measured by the participation of the mother in contributing to family income and her management of the family resources does not indicate any impact on the level of neonatal and infant mortality. Such results in the context of our study could be attributed to the existence of a socio-cultural burden that is restrictive and presents an improvement in the decision-making power of women within households (through their income and their contribution to the household budget) which could translate into an improvement in the well-being of children in particular and the family in general.

In addition, the results demonstrate that economic empowerment continues to reduce infant and child mortality for mothers who have a certain level of education and participate in the generation of family income. For example, the probability of death among children aged 5 years and below (infant and child mortality) decreases by 13% when the mother participated in generating family income and by 26% when they participate in decisions concerning family expenditure. The underlying argument is thus that families in which the mothers are not only educated but also participate in decision making about household expenditure are more inclined towards dedicating a significant percentage of their income on healthcare expenditure and on maintaining good nutritional status that is favourable to their well-being (

Smith et al., 2004;

Carlson et al., 2015;

Essilfie et al., 2020). Also, due to a better knowledge and sensitization on healthcare and the prevention of illnesses, educated mothers take care of their child and themselves during and after a pregnancy better than uneducated mothers do.

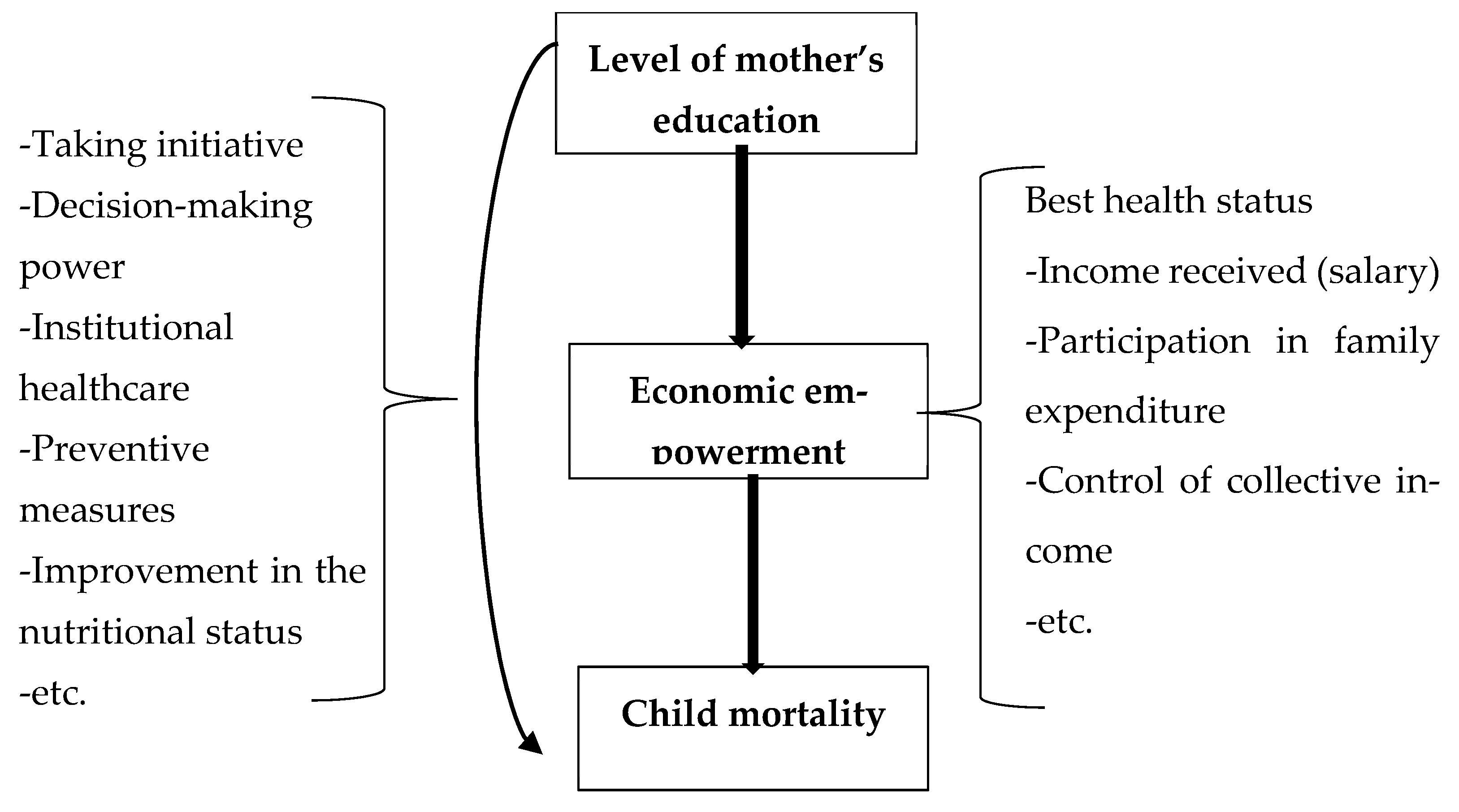

Thus, in conformity with the conceptual framework of this study, economic empowerment of mothers is presented by one of the channels of transmission of the impacts of the level of education of the woman on child mortality in Burkina Faso. However, the results corroborate those of various studies such as those of

Carlson et al. (

2015) and

Essilfie et al. (

2020).

Furthermore, the results reveal that the various mortality rates seem better explained through other socio-economic and demographic aspects; notably, the social class of the family (middle class or rich), the region in which the household lives, the place of birth of the child and the age of the mother at her first child birth have an impact on the probability of the death of the children. Indeed, if the wife belongs to the middle class or the rich, neonatal, infant and child mortality rates are reduced. Similarly, we noted that being born in a health centre reduces the probability of death. However, practising a traditional religion had a positive impact on neonatal, infant and child mortality. This could be explained by the fact that the gender norms are more pronounced within traditional communities. In addition, the healthcare decisions of a family have various impacts on child mortality. For example, if the decision is made by the mother and her partner, the probability of death among the children increases, whereas it decreases if the decision is made by the mother and someone else. The mother’s age at the time of her first childbirth is also a determinant in explaining the risks of deaths among children. If the mother had her first child between 20 and 30 years of age, mortality reduces; however, if she is aged above 30 years, mortality increases.

In summary, we noted that, in Burkina Faso, the improvement in human capital of women is favourable to their economic empowerment. Indeed, access to education, in other words to training in school and in literacy classes for women, improves their income probability. Nevertheless, it seems not to have an impact on their decision-making capacity in regard to household income. It is also evident that the decision-making capacity in terms of household income reduces child mortality in Burkina Faso, especially in rural areas.