Childhood Migration Experiences and Entrepreneurial Choices: Evidence from Chinese Internal Migrants

Abstract

1. Introduction

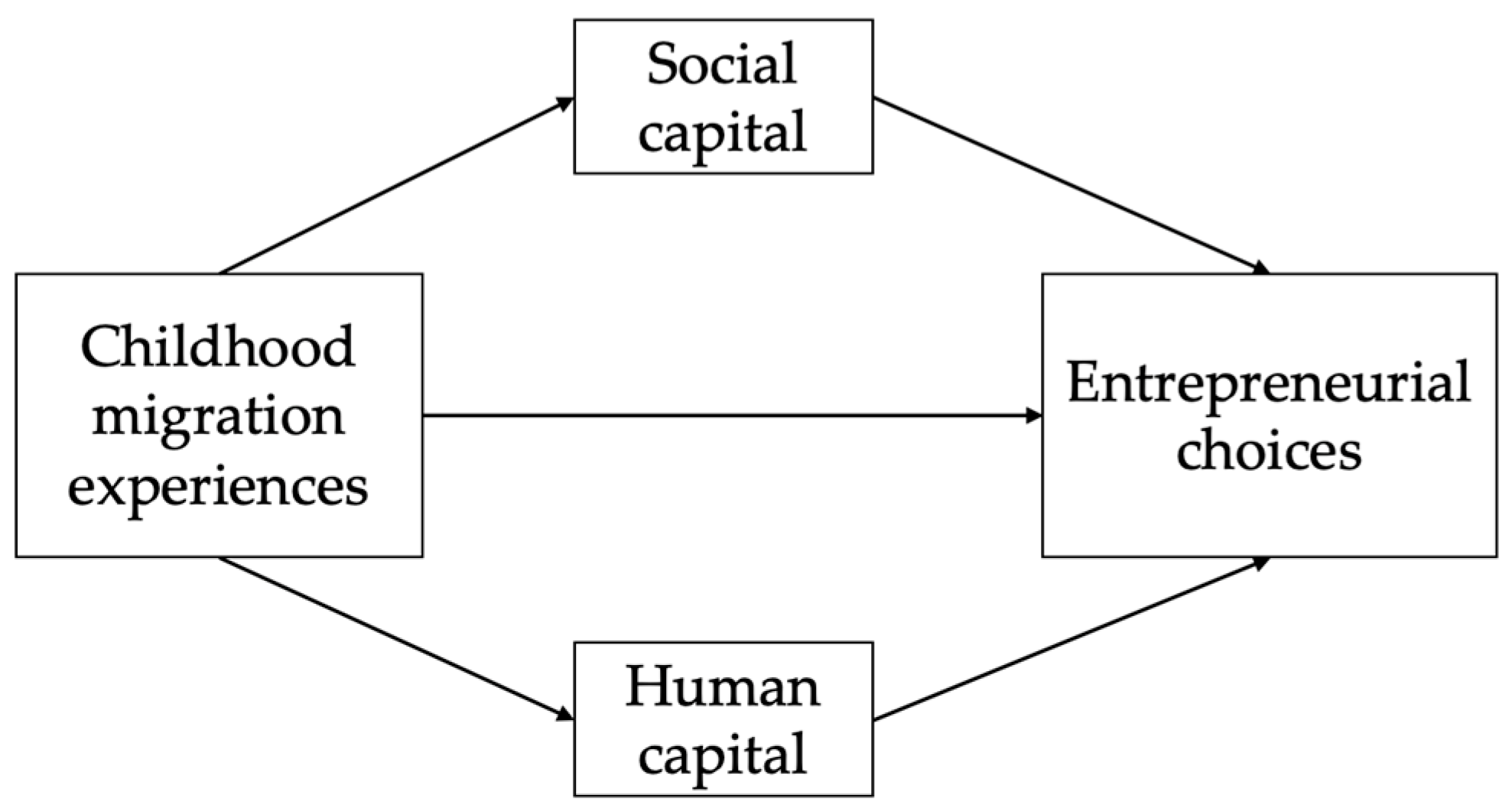

2. Related Literature and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Social Capital

2.2. Human Capital

3. Methodology

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variable

3.2.3. Instrumental Variables

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.2.5. Mediating Variables

3.3. Empirical Design

3.3.1. Baseline Regression

3.3.2. Mediation Analysis

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Summary Statistics

4.2. Baseline Regression Results

4.3. Addressing the Issue of Endogeneity

4.3.1. IV Estimations

4.3.2. Propensity Score Matching

4.3.3. Doubly Robust Estimation

4.4. Robustness Checks

4.5. Mediating Effects Analysis

- Social capital of the hometown exhibits an indirect effect of 0.00038, accounting for merely 0.80% of the total effect. From a life course perspective, childhood migration may enable individuals to retain some social connections and capital from their family or hometown, which could shape adult entrepreneurship through the continuity of such resources. However, this effect is negligible in our analysis. One possible explanation is that migration weakens original ties (Z. Huang et al., 2023), offsetting their positive role and resulting in only a weak positive trend. A more critical reason may lie in the structural limitations of such a type of social capital: migrant populations (and their families) often come from regions with relatively poor rural regions, where the local resources supporting entrepreneurship, such as access to funding, market information, and industrial networks, are inherently scarce (J. Zhao & Li, 2021). Even if individuals’ social ties to their hometowns are not completely severed, the resources embedded in these relationships may be insufficient to meet the demands of entrepreneurship. In other words, for the migrant children in this study, the social capital derived from their hometowns that they possess and can access may be more focused on providing basic support for life adaptation and emotional needs, rather than supporting high-risk entrepreneurial activities. This explains why the mediating pathway shows only a weak trend in our model.

- Social capital of the destination has an indirect effect coefficient of 0.00026, contributing 0.55% to the total effect. While life course theory suggests that early migration experiences are expected to promote the restructuring of social networks and the accumulation of social capital in the destination, our results provide no substantive empirical evidence for this pathway. The absence of a significant effect may be attributed to a dilemma faced by individuals who experienced childhood migration. First, as migrant children or adolescents, their limited social integration capacity (a consequence of early-life migration) hinders the effective establishment of high-quality new networks. Second, structural constraints in the destination further exacerbate this issue: migrant groups (especially those who moved in childhood) often face subtle social exclusion or cultural barriers (Hermansen, 2017; Xia & Ma, 2020). Even if they form new networks, these ties tend to be limited to other migrant groups with similar socioeconomic backgrounds, lacking the diversity and resource richness required to facilitate entrepreneurship.

- Education has an indirect effect coefficient of 0.01689, accounting for 35.14% of the total effect, making it the most core mediator. Among all stages of life, the return on human capital investment in childhood is the highest, and thus the impact of early migration on individuals’ educational trajectories will have long-term effects on their subsequent development. Unlike some studies that emphasize educational exclusion faced by migrant children (Xia & Ma, 2020), we do not observe the negative effects of migration on education here. This discrepancy may originate from the characteristics of our sample. As shown in Table 1, the proportion of respondents who first migrated during high school is 23.6%, which is much higher than that of migrant children in other age groups. For this group, the barriers to urban compulsory education, often tied to hukou, had minimal influence, which may explain why we did not find a negative impact of migration on education. Moreover, our findings align with those of Sieg et al. (2023), which demonstrate that implementing hukou system reforms helps improve the educational quality of migrant children in third-tier cities, thereby increasing their college enrollment rates. Furthermore, for individuals with childhood migration experiences, greater educational attainment plays a positive role in facilitating their entrepreneurial decisions, which validates the positive effect of education on entrepreneurship (Millan et al., 2014), as education enhances individuals’ ability to process information, evaluate risks, and access entrepreneurial resources critical for initiating and sustaining business activities.

- Health status has an indirect effect coefficient of −0.00003, accounting for just −0.06% of the total effect. Early-life migration may have an underlying long-term impact on an individual’s health status due to sudden changes in living environments, which could influence their subsequent economic decision-making (including entrepreneurship). Our results indicate that while childhood migration might indirectly reduce the probability of starting a business by lowering health levels, this is not a primary pathway.

4.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.6.1. Gender Grouped Regression

4.6.2. Childhood Migration Stage Grouped Regression

4.6.3. Age Grouped Regression

4.6.4. Status of First-Time Migration Grouped Regression

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CMDS | China Migrants Dynamic Survey |

| PPS | Probability Proportional to Size |

| GEM | Global Entrepreneurship Monitor |

| IV | Instrumental Variable |

| ECMWF | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts |

| FE | Fixed Effect |

| CPC | Communist Party of China |

| 2SLS | Two-Stage Least Squares |

| MLE | Maximum Likelihood Estimation |

| CMP | Conditional Mixed Process |

| PSM | Propensity Score Matching |

| ATT | Average Treatment Effect on the Treated |

| ATU | Average Treatment Effect on the Untreated |

| ATE | Average Treatment Effect |

| IPWRA | Inverse-Probability Weights Regression Adjustment |

| KHB | Karlson-Holm-Breen |

| APE | Average Partial Effects |

| SUEST | Seemingly Unrelated Estimation and Testing |

Appendix A

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

| Panel A. Entrepreneurial choices | |

| Entrepreneurship | =1 if the respondent was an employer or self-employed; 0 otherwise |

| Self-employment | =1 if the respondent was self-employed; 0 otherwise |

| Employer entrepreneurship | =1 if the respondent was an employer; 0 otherwise |

| Panel B. Migration experiences in childhood | |

| Childhood migration experience | =1 if the respondent had migration experience in childhood (0–18 years old); 0 otherwise |

| First migration during preschool | =1 if the respondent migrated for the first time during preschool (0–6 years old); 0 otherwise |

| First migration during primary school | =1 if the respondent migrated for the first time during primary school (7–12 years old); 0 otherwise |

| First migration during high school | =1 if the respondent migrated for the first time during high school (13–18 years old); 0 otherwise |

| Panel C. Instrumental variables | |

| Proportion of migrant children | The proportion of migrant children (excluding the respondents themselves) in the same origin-county |

| Annual precipitation | The annual precipitation of the origin-county in the year of the respondent’s first migration (unit: meter) |

| Panel D. Control variables | |

| Individual characteristics | |

| Gender | Male = 1; female = 0 |

| Age | Age of the respondent |

| Age2 | Age squared divided by 100 |

| Education | Years of formal education of the respondent (No formal education = 0; primary education = 6; junior high school = 9; senior high school = 12; college’s degree = 15; bachelor’s degree = 16; master’s or doctoral degree = 19) |

| Ethnicity | =1 if the respondent was of Han ethnicity; 0 otherwise |

| CPC membership | =1 if the respondent was member of the Communist Party of China; 0 otherwise |

| Marital status | =1 if the respondent was married/remarried/cohabiting; 0 otherwise |

| Health status | =1 if the respondent considered him/herself healthy; 0 otherwise |

| Chronic disease | =1 if the respondent was clinically diagnosed with high blood pressure and/or type 2 diabetes; 0 otherwise |

| Household characteristics | |

| Homeownership in destination | =1 if the respondent owned the house that currently lives in; 0 otherwise |

| Total household size | Total number of household members live together in current residence |

| Household expenditure | The logarithm of average total monthly household expenditure over the past year (unit: yuan) |

| Household income | The logarithm of average monthly household income over the past year (unit: yuan) |

| Siblings | The number of siblings. |

| Migration characteristics | |

| Scope of current migration | =1 if the respondent migrated from a different province; 0 if the respondent migrated from a different city/county/town within the same province |

| Total years of migration | The cumulative number of years the respondent has migrated |

| Number of migration experience | Total number of cities that the respondent has migrated to |

| Social insurance participation | |

| Health insurance | =1 if the respondent was covered by social health insurance; 0 otherwise |

| Social Insurance Card | =1 if the respondent has obtained a Social Insurance Card; 0 otherwise |

| Residence Permit | =1 if the respondent has obtained a Residence Permit/Temporary Residence Permit; 0 otherwise |

| Regional dummy variable | |

| Origin provinces | 32 provinces/municipalities/autonomous regions/Production and Construction Corps |

| Destination provinces | 32 provinces/municipalities/autonomous regions/Production and Construction Corps |

| Origin cities | 331 cities |

| Destination cities | 351 cities |

| Origin counties | 2459 counties |

| Destination counties | 1285 counties |

| Variables | Definition | Original Items |

|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Social capital | ||

| Social capital of the hometown | =1 if respondent has participated in the activities of fellow-townsmen associations, or hometown chambers of commerce; =0 otherwise. | 1.Have you participated in the activities of the following organizations in your local area since 2016? Options: A. Fellow-townsmen associations; B. Hometown chambers of commerce; C. Trade unions; D. Alumni associations; E. Volunteer associations; F. Others. |

| Social capital of the destination | =1 if the respondent has participated in the activities of trade unions, alumni associations or volunteer associations; =0 otherwise. | Same as above. |

| Panel B. Human capital | ||

| Education | Years of formal education of respondents (No formal education = 0; primary education = 6; junior high school = 9; senior high school = 12; college’s degree = 15; bachelor’s degree = 16; master’s or doctoral degree = 19). | 1.Level of education. Options: A. No formal education; B. Primary education; C. Junior high school; D. Senior high school; E. College’s degree; F. Bachelor’s degree; G. Master’s or doctoral degree. |

| Health status | =1 if the respondent considered him/herself “Health” or “Mostly healthy”; 0 otherwise. | 1.How would you rate your current health status? Options: A. Health; B. Mostly healthy; C. Unhealthy, but able to take care of myself; D. Unable to take care of myself. |

| Variable | Unmatched and Matched | Mean | Bias (%) | Bias Reduction (%) | t-Test | V(T)/ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated | Control | t | p Value | V(C) | ||||

| Gender | Unmatched | 0.608 | 0.554 | 11.1 | 15.01 | 0.000 | . | |

| Matched | 0.608 | 0.622 | −3.0 | 75.7 | −3.05 | 0.002 | . | |

| Age | Unmatched | 30.035 | 36.327 | −81.1 | −106.62 | 0.000 | 0.73 * | |

| Matched | 30.036 | 30.137 | −1.3 | 98.4 | −1.62 | 0.106 | 1.04 * | |

| Education | Unmatched | 9.902 | 9.872 | 1.0 | 1.33 | 0.185 | 0.65 * | |

| Matched | 9.902 | 9.870 | 1.1 | −6.9 | 1.26 | 0.206 | 0.72 * | |

| Ethnicity | Unmatched | 0.912 | 0.915 | −0.9 | −1.17 | 0.241 | . | |

| Matched | 0.912 | 0.913 | −0.5 | 45.7 | −0.52 | 0.602 | . | |

| CPC membership | Unmatched | 0.026 | 0.036 | −5.8 | −7.60 | 0.000 | . | |

| Matched | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.1 | 98.4 | 0.11 | 0.911 | . | |

| Marital status | Unmatched | 0.743 | 0.848 | −26.2 | −37.50 | 0.000 | . | |

| Matched | 0.743 | 0.745 | −0.6 | 97.6 | −0.64 | 0.520 | . | |

| Health status | Unmatched | 0.992 | 0.987 | 4.8 | 6.21 | 0.000 | . | |

| Matched | 0.992 | 0.993 | −1.1 | 76.2 | −1.51 | 0.131 | . | |

| Chronic disease | Unmatched | 0.023 | 0.038 | −8.9 | −11.52 | 0.000 | . | |

| Matched | 0.023 | 0.021 | 1.0 | 88.8 | 1.31 | 0.190 | . | |

| Homeownership in destination | Unmatched | 0.220 | 0.231 | −2.6 | −3.52 | 0.000 | . | |

| Matched | 0.220 | 0.216 | 0.8 | 68.4 | 0.93 | 0.353 | . | |

| Total household size | Unmatched | 3.267 | 3.181 | 7.1 | 9.92 | 0.000 | 1.19 * | |

| Matched | 3.267 | 3.268 | −0.1 | 98.7 | −0.10 | 0.922 | 0.85 * | |

| Household expenditure | Unmatched | 8.064 | 7.985 | 13.0 | 17.89 | 0.000 | 1.08 * | |

| Matched | 8.064 | 8.070 | −0.9 | 93.0 | −1.00 | 0.317 | 1.02 * | |

| Household income | Unmatched | 8.767 | 8.676 | 16.3 | 22.45 | 0.000 | 1.11 * | |

| Matched | 8.767 | 8.770 | −0.6 | 96.0 | −0.70 | 0.482 | 1.00 * | |

| Sample | Pseudo-R2 | LR Statistics (p-Value) | Bias of Mean | Bias of Median | B | R | % of Obs. in the Treated Group with a Suitable Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmatched | 0.150 | 16531.40 (0.000) | 14.9 | 8.0 | 99.7 * | 0.83 | 100 |

| NN matching | 0.000 | 18.99 (0.089) | 0.9 | 0.9 | 3.9 | 1.09 | 60 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | ||||||||

| Childhood migration experience | 0.015 *** (0.004) | 0.013 *** (0.004) | 0.026 *** (0.004) | 0.024 *** (0.003) | 0.029 *** (0.004) | 0.023 ** (0.009) | 0.028 *** (0.004) | 0.031 *** (0.007) |

| Individual characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Household characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Migration characteristics | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Social insurance participation | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dest. Prov. FE | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Orig. Prov. FE | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dest. City FE | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Orig. City FE | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dest. County FE | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Orig. County FE | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| N | 95,825 | 88,258 | 95,584 | 93,131 | 89,312 | 13,427 | 65,771 | 16,598 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Employment | ||||||||

| Childhood migration experience | 0.010 *** (0.004) | 0.015 *** (0.004) | 0.015 *** (0.003) | 0.020 *** (0.003) | 0.016 *** (0.004) | 0.012 (0.010) | 0.015 *** (0.004) | 0.019 *** (0.007) |

| Individual characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Household characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Migration characteristics | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Social insurance participation | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dest. Prov. FE | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Orig. Prov. FE | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dest. City FE | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Orig. City FE | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dest. County FE | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Orig. County FE | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| N | 95,825 | 88,258 | 95,708 | 93,131 | 89,312 | 13,435 | 65,771 | 16,598 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employer Entrepreneurship | ||||||||

| Childhood migration experience | 0.004 *** (0.002) | 0.011 *** (0.002) | 0.011 *** (0.002) | 0.013 *** (0.002) | 0.012 *** (0.002) | 0.009 * (0.005) | 0.012 *** (0.002) | 0.011 *** (0.003) |

| Individual characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Household characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Migration characteristics | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Social insurance participation | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dest. Prov. FE | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Orig. Prov. FE | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dest. City FE | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Orig. City FE | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Dest. County FE | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Orig. County FE | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| N | 95,808 | 88,241 | 93,968 | 76,705 | 89,295 | 13,414 | 65,771 | 16,562 |

| 1 | Since the research is about entrepreneurial behavior in adulthood, the minimum age of the sample is set at 18. The earliest birth year of the sample was set to 1965, considering the impact of the Great famine of 1959–1961 on human capital (Cui et al., 2020). |

| 2 | Specifically, these are individuals who were neither employed by others, self-employed, nor engaged in entrepreneurship. This group accounts for 17.74% of the initial dataset. |

| 3 | Age of first migration = (year of first departure from domicile − year of birth) + (month of first departure from domicile − month of birth)/12. |

| 4 | In fact, the results of the indirect effects from the KHB mediation analyses are highly consistent, irrespective of whether the outcome variable is defined as self-employment alone or as entrepreneurship (combining both self-employment and employer entrepreneurship). |

| 5 | Since the CMP program cannot test the validity of instrumental variables, we used the 2SLS method of the linear model as an alternative. For the 2SLS estimation, the F-test of excluding instruments yields a value of 496.77. The Anderson canonical correlation LM statistic is 983.826 (p < 0.01), and the Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic is 496.772. These results indicate that the instrumental variables are valid. |

| 6 | Rosenbaum and Rubin (1985) suggest that standardized differences of less than 20% between the samples of the treatment and control groups after matching implies that the matching was successful. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | The grouping of migration types is based on the relative economic gap in per capita GDP between the destination and origin provinces, calculated as: Economic Gap = (per capita GDP of destination province − per capita GDP of origin province) ÷ per capita GDP of origin province. |

References

- Ackah, C., Görg, H., Hanley, A., & Hornok, C. (2024). Africa’s businesswomen–underfunded or underperforming? Small Business Economics, 62(3), 1051–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidis, R., Welter, F., Smallbone, D., & Isakova, N. (2007). Female entrepreneurship in transition economies: The case of Lithuania and Ukraine. Feminist Economics, 13(2), 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, S., & Link, A. N. (2018). Under the AEGIS of knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship: Employment growth and gender of founders among European firms. Small Business Economics, 50(4), 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A. R., & Miller, C. J. (2003). “Class matters”: Human and social capital in the entrepreneurial process. The Journal of Scio-Economics, 32(1), 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenius, P., & Minniti, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athukorala, P. C., & Wei, Z. (2018). Economic transition and labour market dynamics in China: An interpretative survey of the ‘turning point’ debate. Journal of Economic Surveys, 32(2), 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, L. V. (2012). Guest-worker migration, human capital and fertility. Review of Development Economics, 16(2), 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, L. V. (2020). Health capital provision and human capital accumulation. Oxford Economic Papers, 72(3), 633–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay, P., Jones, B. F., Kim, J. D., & Miranda, J. (2020). Age and high-growth entrepreneurship. American Economic Review: Insights, 2(1), 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åslund, O., Böhlmark, A., & Skans, O. N. (2015). Childhood and family experiences and the social integration of young migrants. Labour Economics, 35(C), 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y., Yang, N., Wang, L., & Zhang, S. (2022). The impacts of maternal migration on the cognitive development of preschool-aged children left behind in rural China. World Development, 158, 106007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastié, F., Cussy, P., & Le Nadant, A. L. (2016). Network or independent business? Entrepreneurs’ human, social and financial capital as determinants of mode of entry. Managerial and Decision Economics, 37(3), 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A. (2023). Does internal migration contribute to the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic inequalities? The role of childhood migration. Demography, 60(4), 1059–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, X., & Wang, Y. (2025). Family Strategies for rural-to-urban migrant children under the points-based admission policy in China. Sustainability, 17(2), 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonikowska, A., & Hou, F. (2010). Reversal of fortunes or continued success? Cohort differences in education and earnings of childhood immigrants. International Migration Review, 44(2), 320–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P., & Richardson, J. G. (1986). Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. The Forms of Capital, 241, 258. [Google Scholar]

- Carletto, C., & Kilic, T. (2011). Moving up the ladder? The impact of migration experience on occupational mobility in Albania. Journal of Development Studies, 47(6), 846–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., & Hu, M. (2021). City-level hukou-based labor market discrimination and migrant entrepreneurship in China. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 27(5), 1095–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Guo, W., & Liu, M. (2021). Childhood migration and work motivation in Adulthood: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Research, 132(C), 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., & Wang, J. (2015). Social integration of new-generation migrants in Shanghai China. Habitat International, 49, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., & Barcus, H. R. (2024). The rise of home-returning women’s entrepreneurship in China’s rural development: Producing the enterprising self through empowerment, cooperation, and networking. Journal of Rural Studies, 105, 103156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., & Smyth, R. (2021). Education and migrant entrepreneurship in urban China. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 188, 506–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohodes, E. M., Kribakaran, S., Odriozola, P., Bakirci, S., McCauley, S., Hodges, H. R., Sisk, L. M., Zacharek, S. J., & Gee, D. G. (2021). Migration-related trauma and mental health among migrant children emigrating from Mexico and Central America to the United States: Effects on developmental neurobiology and implications for policy. Developmental Psychobiology, 63(6), e22158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronel-Pangol, K., Paule-Vianez, J., & Orden-Cruz, C. (2024). Conventional or alternative financing to promote entrepreneurship? An analysis of female and male entrepreneurship in developed and developing countries. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 20(1), 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, S. R. (2022). Entrepreneurship and economic growth: Does gender matter? International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 14(1), 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H., Smith, J. P., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Early-life deprivation and health outcomes in adulthood: Evidence from childhood hunger episodes of middle-aged and elderly Chinese. Journal of Development Economics, 143, 102417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brauw, A., & Giles, J. (2017). Migrant opportunity and the educational attainment of youth in rural China. Journal of Human Resources, 52(1), 272–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carolis, D. M., & Saparito, P. (2006). Social capital, cognition, and entrepreneurial opportunities: A theoretical framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D., Kaciak, E., & Thongpapanl, N. (2022). Tacking into the wind: How women entrepreneurs can sail through family-to-work conflict to ensure their firms’ entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 12(3), 263–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H., Dong, W., & Qin, C. (2025). Does migrant working experience stimulate returnees’ entrepreneurship: Evidence from rural China. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 229, 106865. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, E. (2021). Social capital and entrepreneurial financing choice. Journal of Corporate Finance, 70, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkafrawi, N., & Refai, D. (2022). Egyptian rural women entrepreneurs: Challenges, ambitions and opportunities. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 23(3), 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1990). Some empirical aspects of entrepreneurship. In The economics of small firms (pp. 79–99). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie, R. W. (2005). Entrepreneurship and earnings among young adults from disadvantaged families. Small Business Economics, 25, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L., Sun, R. C., & Yuen, M. (2016). Acculturation, economic stress, social relationships and school satisfaction among migrant children in urban China. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17, 507–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2015). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Gibb, L. C., & Nielsen, K. (2014). Entrepreneurship within urban and rural areas: Creative people and social networks. Regional studies, 48(1), 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu Keung Wong, D., Chang, Y., He, X., & Wu, Q. (2010). The protective functions of relationships, social support and self-esteem in the life satisfaction of children of migrant workers in Shanghai, China. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 56(2), 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, G., & Impicciatore, R. (2022). Breaking down the barriers: Educational paths, labour market outcomes and wellbeing of children of immigrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(10), 2305–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J., & Rao, N. (2023). Early learning opportunities of preschool children affected by migration in China. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 63, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M., Mandakovic, V., Apablaza, M., & Arriagada, V. (2021). Are migrants in/from emerging economies more entrepreneurial than natives? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halek, M., & Eisenhauer, J. G. (2001). Demography of risk aversion. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 68(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatak, I., & Zhou, H. (2021). Health as human capital in entrepreneurship: Individual, extension, and substitution effects on entrepreneurial success. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(1), 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermansen, A. S. (2017). Age at arrival and life chances among childhood immigrants. Demography, 54(1), 201–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hincapié, A. (2020). Entrepreneurship over the life cycle: Where are the young entrepreneurs? International Economic Review, 61(2), 617–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Song, Q., Tao, R., & Liang, Z. (2018). Migration, family arrangement, and children’s health in China. Child Development, 89(2), e74–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., & Jin, S. (2023). Does migration experience reduce villagers’ social capital? Evidence from rural China. Applied Economics, 55(30), 3514–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J. (2011). Which immigrants are most innovative and entrepreneurial? Distinctions by entry visa. Journal of Labor Economics, 29(3), 417–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvide, H. K., & Panos, G. A. (2014). Risk tolerance and entrepreneurship. Journal of Financial Economics, 111(1), 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, S. L. (2005). The role, use and activation of strong and weak network ties: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 42(6), 1233–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, D. A., Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., & Bonin, H. (2010). Direct evidence on risk attitudes and migration. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(3), 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, S. (2021). Social Norms as a Barrier to Women’s Employment in Developing Countries. IMF Economic Review, 69(3), 576–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaland, O. J. (2021). “We have many options, but they are all bad options!”: Aspirations among internal migrant youths in Shanghai, China. The European Journal of Development Research, 33(1), 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlson, K. B., Holm, A., & Breen, R. (2012). Comparing regression coefficients between same-sample nested models using logit and probit: A new method. Sociological Methodology, 42(1), 286–313. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J., Deng, Q., & Li, S. (2011). The puzzle of migrant labour shortage and rural labour surplus in China. China Economic Review, 22(4), 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontinen, T., & Ojala, A. (2011). Network ties in the international opportunity recognition of family SMEs. International Business Review, 20(4), 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. J. (2022). Lingering male breadwinner norms as predictors of family satisfaction and marital instability. Social Sciences, 11(2), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, M., & Minniti, M. (2006). The effect of aging on entrepreneurial behavior. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(2), 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyden, D. P., Link, A. N., & Siegel, D. S. (2014). A theoretical analysis of the role of social networks in entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 43(7), 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Q., Li, L. M. W., & Lou, N. M. (2022). Who moved with you? The companionship of significant others reduces movers’ motivation to make new friends. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 25(2), 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Qiao, S., & Zhang, D. (2024). Childhood migration experience and adult health: Evidence from China’s rural migrants. Archives of Public Health, 82(1), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J., Wang, H., & Lazear, E. P. (2018). Demographics and entrepreneurship. Journal of Political Economy, 126(S1), S140–S196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z., & Chen, Y. P. (2007). The educational consequences of migration for children in China. Social Science Research, 36(1), 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z., Yue, Z., Li, Y., Li, Q., & Zhou, A. (2020). Choices or constraints: Education of migrant children in urban China. Population Research and Policy Review, 39(4), 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. W. (2020). Return migration, online entrepreneurship and gender performance in the Chinese ‘Taobao families’. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 61(3), 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. (2012). Education of children left behind in rural China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(2), 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G. (2020). Migrant status, school segregation, and students’ academic achievement in urban China. Chinese Sociological Review, 52(3), 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G., & Wu, Q. (2019). Social capital and educational inequality of migrant children in contemporary China: A multilevel mediation analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W., Renwick, A., & Bicknell, K. (2018). Higher intensity, higher profit? Empirical evidence from dairy farming in New Zealand. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 69(3), 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B. C., McNally, J. J., & Kay, M. J. (2013). Examining the formation of human capital in entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis of entrepreneurship education outcomes. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(2), 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migrant Population Service Center of NHC. (2023). China migrants dynamic survey 2017 [dataset]. Population Health Data Archive (PHDA) of China. [CrossRef]

- Millan, J. M., Congregado, E., Roman, C., Van Praag, M., & Van Stel, A. (2014). The value of an educated population for an individual’s entrepreneurship success. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), 612–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minola, T., Criaco, G., & Obschonka, M. (2016). Age, culture, and self-employment motivation. Small Business Economics, 46(2), 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, F., Giones, F., & Riverola, C. (2016). Evaluating the impact of prior experience in entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12, 791–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, K. (2003). Networks in the modern economy: Mexican migrants in the US labor market. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(2), 549–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Sabater, J. (2019). ERA5-Land monthly averaged data from 1950 to present [dataset]. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S. M. (1999). Childhood migration and social integration in adulthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(3), 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, C. M., Sewell, M. N., Yoon, H. J., Soto, C. J., & Roberts, B. W. (2021). Social, emotional, and behavioral skills: An integrative model of the skills associated with success during adolescence and across the life span. Frontiers in Education, 6, 679561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H., & Ye, Y. (2018). Entrepreneurship education matters: Exploring secondary vocational school students’ entrepreneurial intention in China. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 27, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusche, D. (2009). What works in migrant education? A review of evidence and policy options. OECD education working papers. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Perreira, K. M., & Ornelas, I. J. (2011). The physical and psychological well-being of immigrant children. The Future of Children, 21, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. (1998). SOCIAL CAPITAL: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. M., Dana, L. P., Moral, I. H., Anjum, N., & Rahaman, M. S. (2023). Challenges of rural women entrepreneurs in Bangladesh to survive their family entrepreneurship: A narrative inquiry through storytelling. Journal of Family Business Management, 13(3), 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q., & Jiang, S. (2021). Acculturation stress, satisfaction, and frustration of basic psychological needs and mental health of Chinese migrant children: Perspective from basic psychological needs theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resosudarmo, B. P., & Suryadarma, D. (2014). The impact of childhood migration on educational attainment: Evidence from rural–urban migrants in Indonesia. Asian Population Studies, 10(3), 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. (2011). Fitting fully observed recursive mixed-process models with cmp. The Stata Journal, 11(2), 159–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1985). Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. The American Statistician, 39(1), 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozelle, S., Taylor, J. E., & DeBrauw, A. (1999). Migration, remittances, and agricultural productivity in China. American Economic Review, 89(2), 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D. B. (2001). Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: Application to the tobacco litigation. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology, 2, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwank, H. (2024). Childhood migration and educational attainment: Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Development Economics, 171, 103338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settersten, R. A., Jr., & Mayer, K. U. (1997). The measurement of age, age structuring, and the life course. Annual Review of Sociology, 23(1), 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2001). Entrepreneurship as a field of research: A response to Zahra and Dess, Singh, and Erikson. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y., & Sun, L. (2021). Entrepreneurs’ social capital and venture capital financing. Journal of Business Research, 136, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieg, H., Yoon, C., & Zhang, J. (2023). The impact of local fiscal and migration policies on human capital accumulation and inequality in China. International Economic Review, 64(1), 57–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S. H., & Morrison, F. J. (2010). The nature and impact of changes in home learning environment on development of language and academic skills in preschool children. Developmental Psychology, 46(5), 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, O. (2018). Social networks and the geography of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 51, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawser, J. A., Hechavarría, D. M., & Passerini, K. (2021). Gender and entrepreneurship: Research frameworks, barriers and opportunities for women entrepreneurship worldwide. Journal of Small Business Management, 59(Suppl. S1), S1–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S. B., & Fong, E. (2022). The role of human capital, race, gender, and culture on immigrant entrepreneurship in Hong Kong. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 34(4), 363–396. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L., Xiang, X., & Liu, Y. (2024). Family migration and well-being of Chinese migrant workers’ children. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 12862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandor, P. (2021). Are voluntary international migrants self-selected for entrepreneurship? An analysis of entrepreneurial personality traits. Journal of World Business, 56(2), 101142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K., Dun, O., & Stal, M. (2008). Field observations and empirical research. Forced Migration Review, 31, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, H., & Wang, C. C. (2024). Social capital and internal migrant entrepreneurship: Evidence from urban China. Cities, 152, 105222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D. F. K., & Leung, G. (2008). The functions of social support in the mental health of male and female migrant workers in China. Health & Social Work, 33(4), 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., & Sun, L. (2020). Social support networks and adaptive behaviour choice: A social adaptation model for migrant children in China based on grounded theory. Children and Youth Services Review, 113, 104940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q., & Cebotari, V. (2018). Experiences of migration, parent–child interaction, and the life satisfaction of children in Ghana and China. Population, Space and Place, 24(7), e2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q., Tsang, B., & Ming, H. (2014). Social capital, family support, resilience and educational outcomes of Chinese migrant children. British Journal of Social Work, 44(3), 636–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., & Ma, Z. (2020). Relative deprivation, social exclusion, and quality of life among Chinese internal migrants. Public Health, 186, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D., & Dronkers, J. (2016). Migrant children in Shanghai: A research note on the PISA-Shanghai controversy. Chinese Sociological Review, 48(3), 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D., & Wu, X. (2022). Separate and unequal: Hukou, school segregation, and educational inequality in urban China. Chinese Sociological Review, 54(5), 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., & Zhang, X. (2023). Persistence of culture: How the entrepreneurial culture of origin contributes to migrant entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 61(3), 1179–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L. (2023, June 28). China’s job market: Age discrimination hits workers over 35. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/28/business/china-jobs-age-discrimination-35.html (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Zhang, T., & Acs, Z. (2018). Age and entrepreneurship: Nuances from entrepreneur types and generation effects. Small Business Economics, 51, 773–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C., & Li, X. (2022). Living under the shadow: Adverse childhood experiences and entrepreneurial behaviors in Chinese adults. Journal of Business Research, 138, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., & Li, T. (2021). Social capital, financial literacy, and rural household entrepreneurship: A mediating effect analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 724605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Zhang, Q., Ji, Y., Liu, H., & Lou, V. W. (2023). Influence of spousal caregiving and living arrangement on depression among husband caregivers in rural China. Aging & Mental Health, 27(7), 1266–1273. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Obs. | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Dependent variables | |||||

| Entrepreneurship | 95,825 | 0.415 | 0.493 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Self-employment | 95,825 | 0.359 | 0.480 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Employer entrepreneurship | 95,825 | 0.056 | 0.229 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Panel B. Independent variables | |||||

| Childhood migration experiences | 95,825 | 0.263 | 0.440 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| First migration during preschool | 95,825 | 0.010 | 0.102 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| First migration during primary school | 95,825 | 0.017 | 0.129 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| First migration during high school | 95,825 | 0.236 | 0.424 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Panel C. Instrumental Variables | |||||

| Proportion of migrant children | 95,825 | 0.263 | 0.097 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Annual precipitation | 95,825 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.012 |

| Panel D. Control Variables | |||||

| Gender | 95,825 | 0.568 | 0.495 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Age | 95,825 | 34.672 | 8.504 | 18.000 | 52.000 |

| Age2 | 95,825 | 12.746 | 6.066 | 3.240 | 27.040 |

| Education | 95,825 | 9.880 | 3.034 | 0.000 | 19.000 |

| Ethnicity | 95,825 | 0.914 | 0.280 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| CPC membership | 95,825 | 0.034 | 0.180 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Marital status | 95,825 | 0.821 | 0.384 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Health status | 95,825 | 0.988 | 0.110 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Chronic disease | 95,825 | 0.034 | 0.181 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Homeownership in destination | 95,825 | 0.228 | 0.419 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Total household size | 95,825 | 3.204 | 1.189 | 1.000 | 10.000 |

| Household expenditure | 95,825 | 8.006 | 0.610 | 3.912 | 11.513 |

| Household income | 95,825 | 8.700 | 0.554 | 3.912 | 12.206 |

| Siblings | 95,825 | 0.036 | 0.214 | 0.000 | 4.000 |

| Scope of current migration | 95,825 | 0.502 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Total years of migration | 95,825 | 11.156 | 7.443 | 0.167 | 47.333 |

| Number of migration experiences | 95,825 | 2.097 | 1.947 | 1.000 | 88.000 |

| Health insurance | 95,825 | 0.949 | 0.221 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Social Insurance Card | 95,825 | 0.513 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Residence Permit | 95,825 | 0.689 | 0.463 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | Entrepreneurship | Self-Employment | Self-Employment | Employer Entrepreneurship | Employer Entrepreneurship | |

| Childhood migration experiences | 0.033 *** (0.004) | 0.029 *** (0.004) | 0.021 *** (0.004) | 0.016 *** (0.004) | 0.012 *** (0.002) | 0.012 *** (0.002) |

| Individual characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Household characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dest. Prov. FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Orig. Prov. FE | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Observations | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.135 | 0.165 | 0.113 | 0.135 | 0.121 | 0.129 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood Migration Experiences | Entrepreneurship | Childhood Migration Experiences | Self-Employment | Childhood Migration Experiences | Employer Entrepreneurship | |

| Proportion of migrant children | 0.235 *** (0.015) | 0.257 *** (0.015) | 0.267 *** (0.015) | |||

| Annual precipitation | 39.491 *** (1.728) | 43.307 *** (1.770) | 46.814 *** (1.575) | |||

| Childhood migration experiences | 0.382 *** (0.014) | 0.275 *** (0.025) | 0.024 ** (0.010) | |||

| Individual characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Household characteristics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dest. Prov. FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Orig. Prov. FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 |

| Wald test of exogeneity | 36396.03 *** | 27382.49 *** | 16788.90 *** | |||

| atanhrho_12 | −0.844 *** | −0.524 *** | −0.074 | |||

| Effects | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | Self-Employment | Employer Entrepreneurship | Entrepreneurship | Self-Employment | Employer Entrepreneurship | |

| PSM | PSM | PSM | IPWRA | IPWRA | IPWRA | |

| ATT | 0.016 *** [0.006] | 0.003 [0.006] | 0.011 *** [0.003] | |||

| ATU | 0.025 *** [0.007] | 0.015 ** [0.007] | 0.015 *** [0.003] | |||

| ATE | 0.025 *** [0.005] | 0.012 ** [0.006] | 0.014 *** [0.003] | 0.022 *** [0.005] | 0.011 ** [0.005] | 0.011 *** [0.002] |

| N | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 |

| Panel A: Decomposition using the APE Method | ||||

| Effect type | Coefficient | 95% conf. interval | ||

| Total effect | 0.048 *** {0.004} | 0.041 to 0.055 | ||

| Direct effect | 0.031 *** {0.004} | 0.024 to 0.038 | ||

| Indirect effect | 0.018 | |||

| Panel B: Summary of confounding | ||||

| Variable | Confounding ratio | Confounding percentage | Distributional Sensitivity | |

| Childhood migration experiences | 1.573 | 36.43 | 0.999 | |

| Panel C: Effects of mediator variables | ||||

| Mediator Variables | Coefficient | Percentage of indirect effect | Percentage contribution of mediators | |

| Social capital of the hometown | 0.00038 {0.00011} | 2.20 | 0.80 | |

| Social capital of the destination | 0.00026 {0.00029} | 1.50 | 0.55 | |

| Education | 0.01689 {0.00063} | 96.46 | 35.14 | |

| Health status | −0.00003 {0.00005} | −0.16 | −0.06 | |

| Entrepreneurship | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) |

| Male | Female | First Migration Before Age 6 | First Migration Between Age 7–12 | First Migration Between Age 13–18 | Age ≥ 35 | Age < 35 | Alone at the Time of the First-Time Migration | First-Time Migration with Family/Friends | |

| Childhood migration experiences | 0.029 ** (0.005) | 0.030 *** (0.006) | 0.005 (0.015) | 0.043 *** (0.011) | 0.024 *** (0.004) | 0.029 *** (0.007) | 0.018 *** (0.004) | 0.058 *** (0.005) | 0.00004 *** (0.005) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dest. Prov. FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Orig. Prov. FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| p value of the coefficient difference | 0.434 | 0.046 | 0.360 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.000 | |||

| N | 54,447 | 41,374 | 95,825 | 95,825 | 95,825 | 44,004 | 51,813 | 40,390 | 55,429 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.153 | 0.185 | 0.164 | 0.164 | 0.165 | 0.121 | 0.186 | 0.180 | 0.155 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bu, W.; Liu, S.; Li, C. Childhood Migration Experiences and Entrepreneurial Choices: Evidence from Chinese Internal Migrants. Economies 2025, 13, 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13110330

Bu W, Liu S, Li C. Childhood Migration Experiences and Entrepreneurial Choices: Evidence from Chinese Internal Migrants. Economies. 2025; 13(11):330. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13110330

Chicago/Turabian StyleBu, Wei, Shanshan Liu, and Chenxi Li. 2025. "Childhood Migration Experiences and Entrepreneurial Choices: Evidence from Chinese Internal Migrants" Economies 13, no. 11: 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13110330

APA StyleBu, W., Liu, S., & Li, C. (2025). Childhood Migration Experiences and Entrepreneurial Choices: Evidence from Chinese Internal Migrants. Economies, 13(11), 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13110330