Bibliometric and Content Analysis on Central Bank Digital Currencies for the Period 2018–2025 and a Policy Model Proposal for Türkiye †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. CBDCs, Consumer Behavior, and Welfare

2.2. The Impact of CBDCs on the Banking Sector

2.3. The Impact of CBDCs on Financial Stability

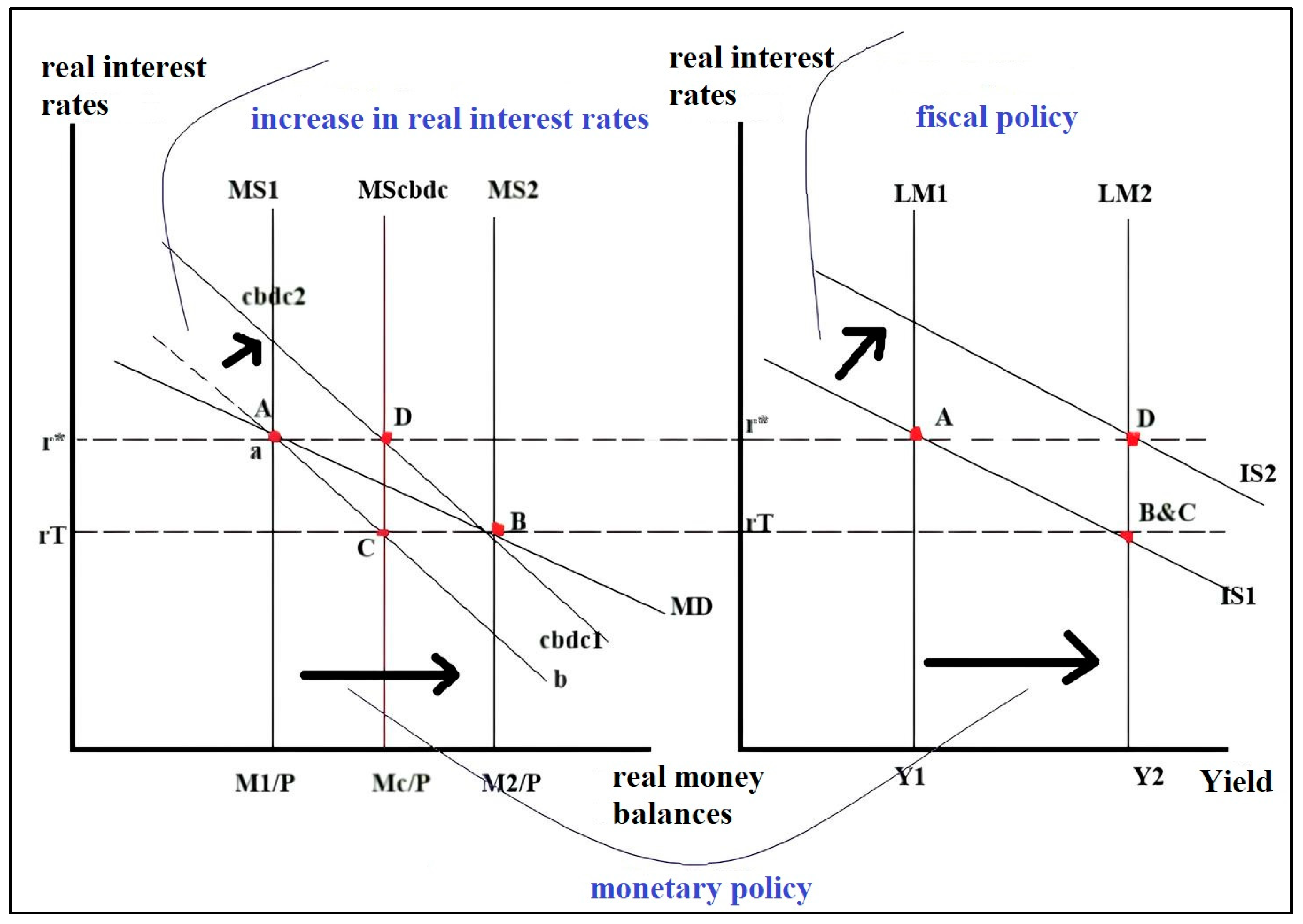

2.4. The Impact of CBDCs on Monetary Policy

2.5. The Impact of CBDCs on Fiscal Policy

2.6. The Harmonization of Monetary and Fiscal Policies Through CBDCs

3. Methodology and Findings

3.1. Methodology

3.1.1. Research Topic and Objective

3.1.2. Research Model

3.1.3. Research Questions

- How has research on CBDCs evolved over the years?

- What are the critical and popular topics related to CBDCs in the scientific literature and research projects? In which fields is CBDC-related research most concentrated?

- What would be the potential contributions of the conceptually proposed CBDC model to Turkey’s monetary and fiscal policies?

3.1.4. Research Population and Sample

3.1.5. Data Collection Technique

3.2. Research Plan

3.3. Research Findings

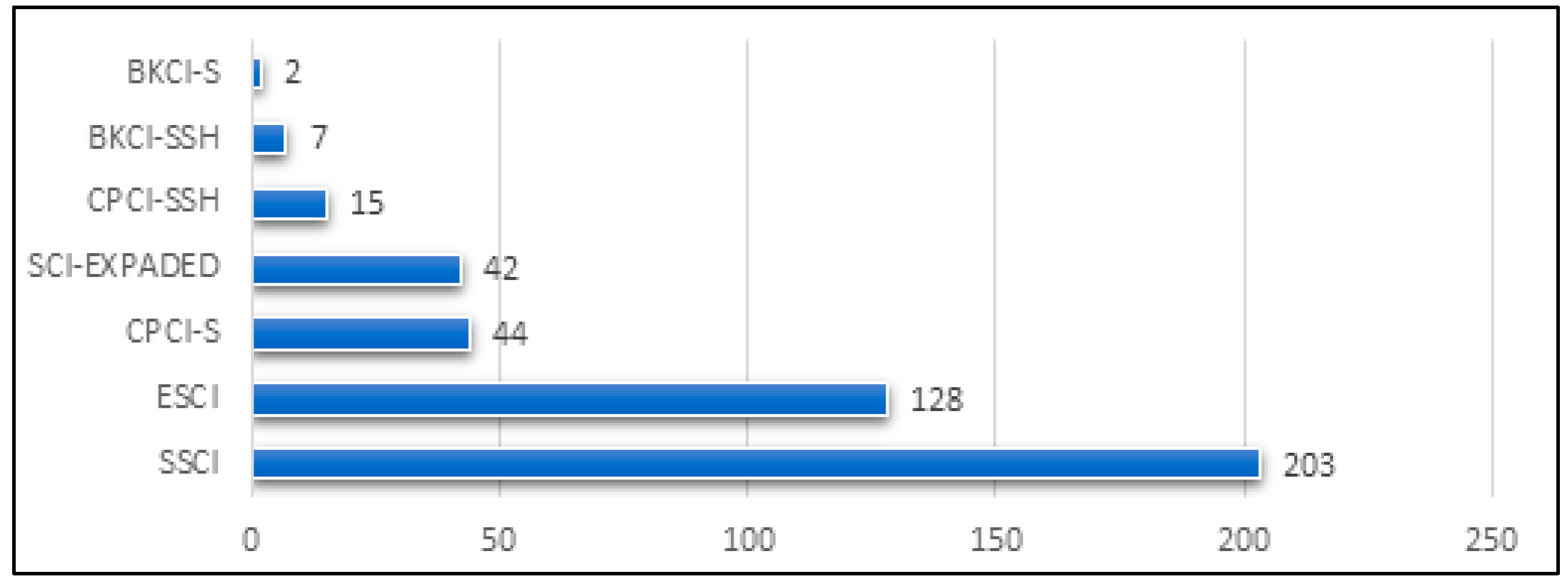

3.3.1. Findings from the Bibliometric Analysis

Description of the Literature Data

Publication Types

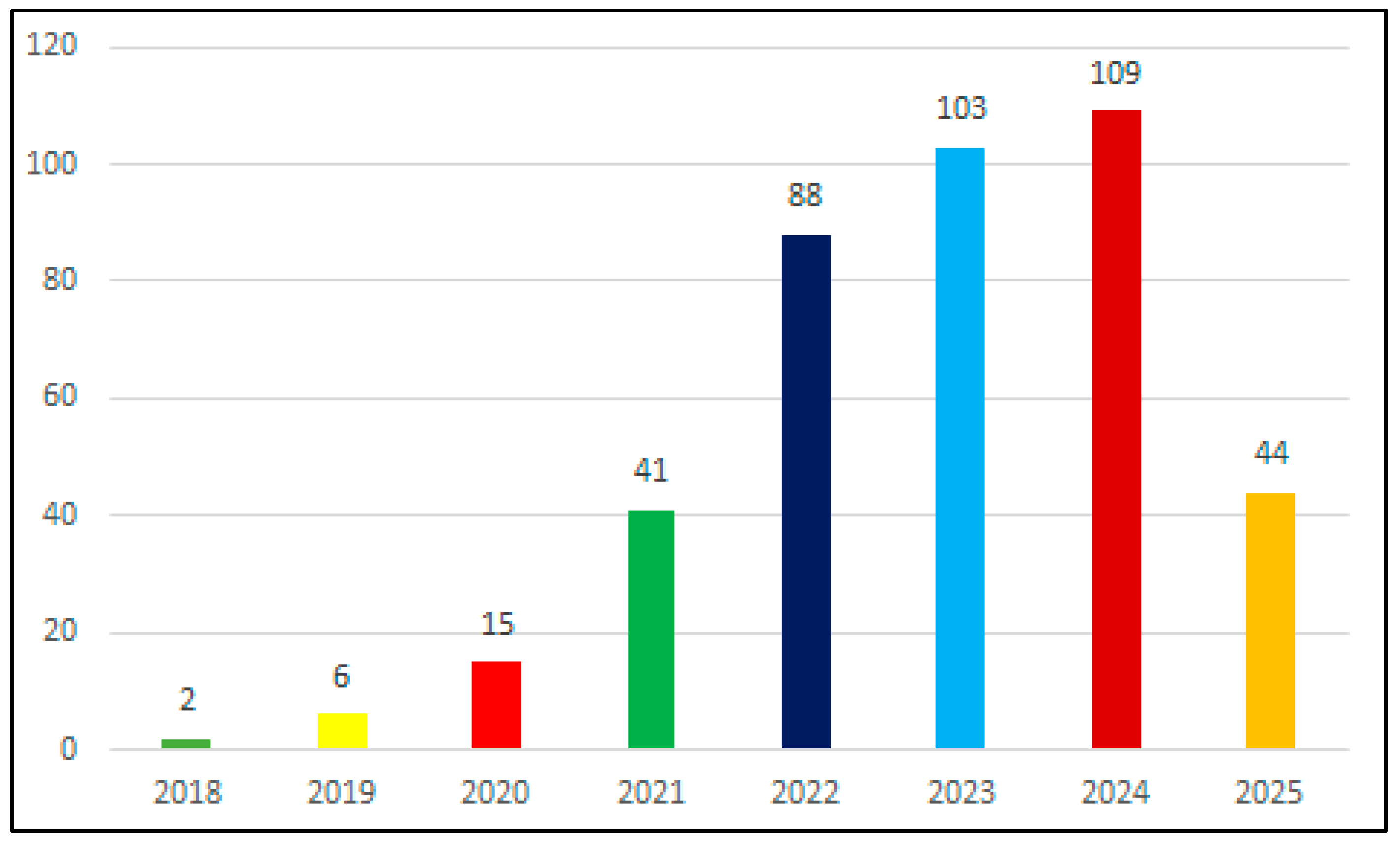

Annual Publications and Citations

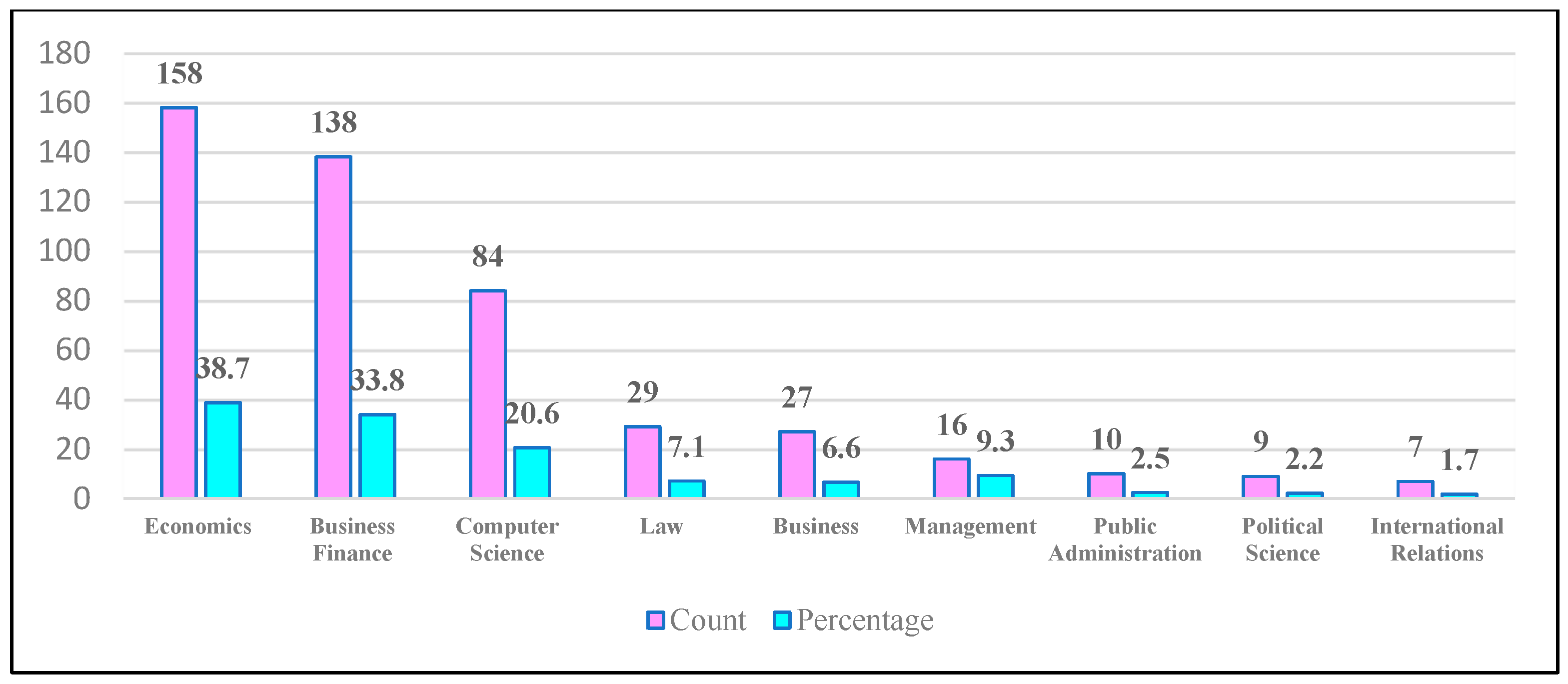

Subject Areas

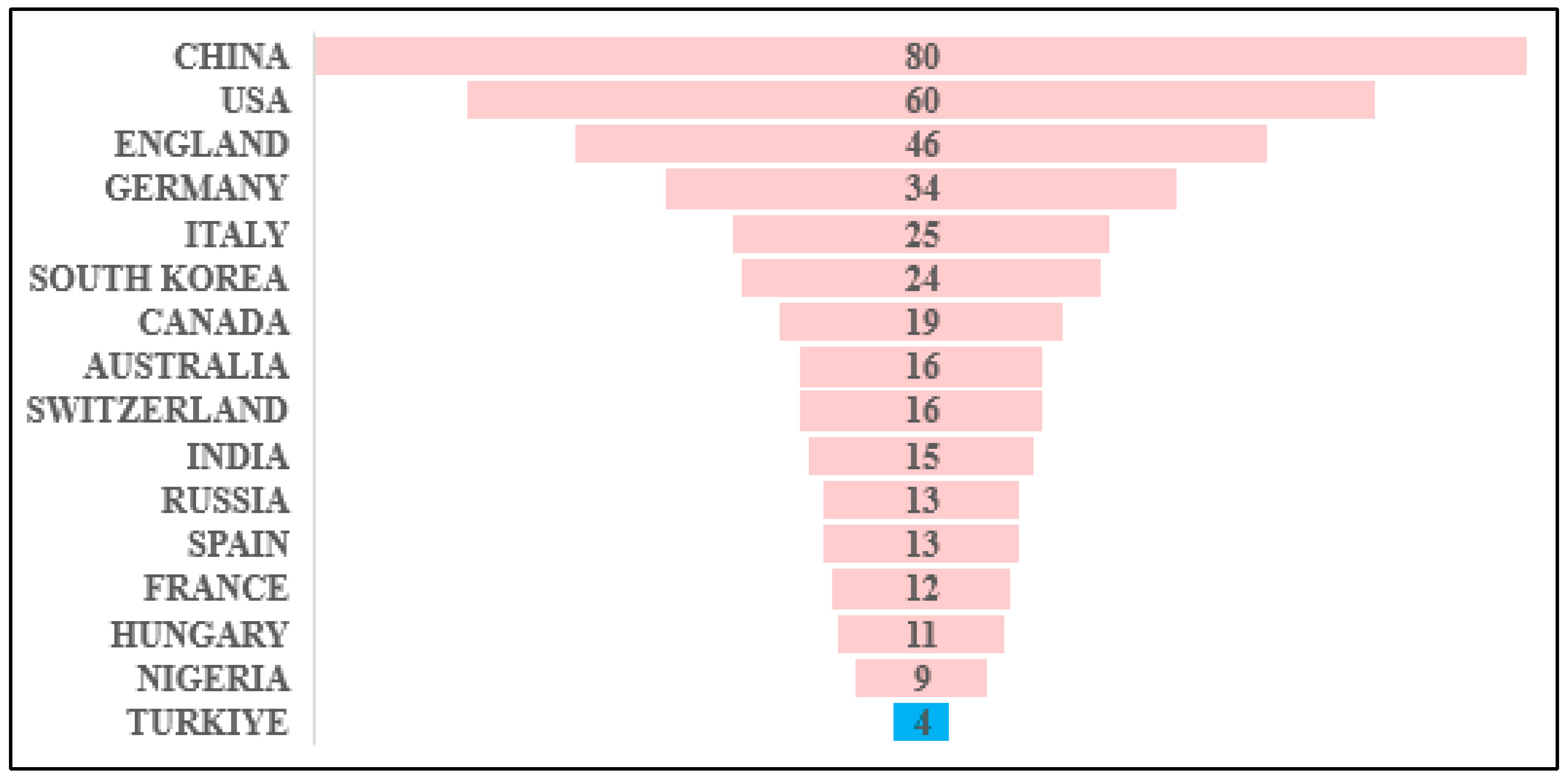

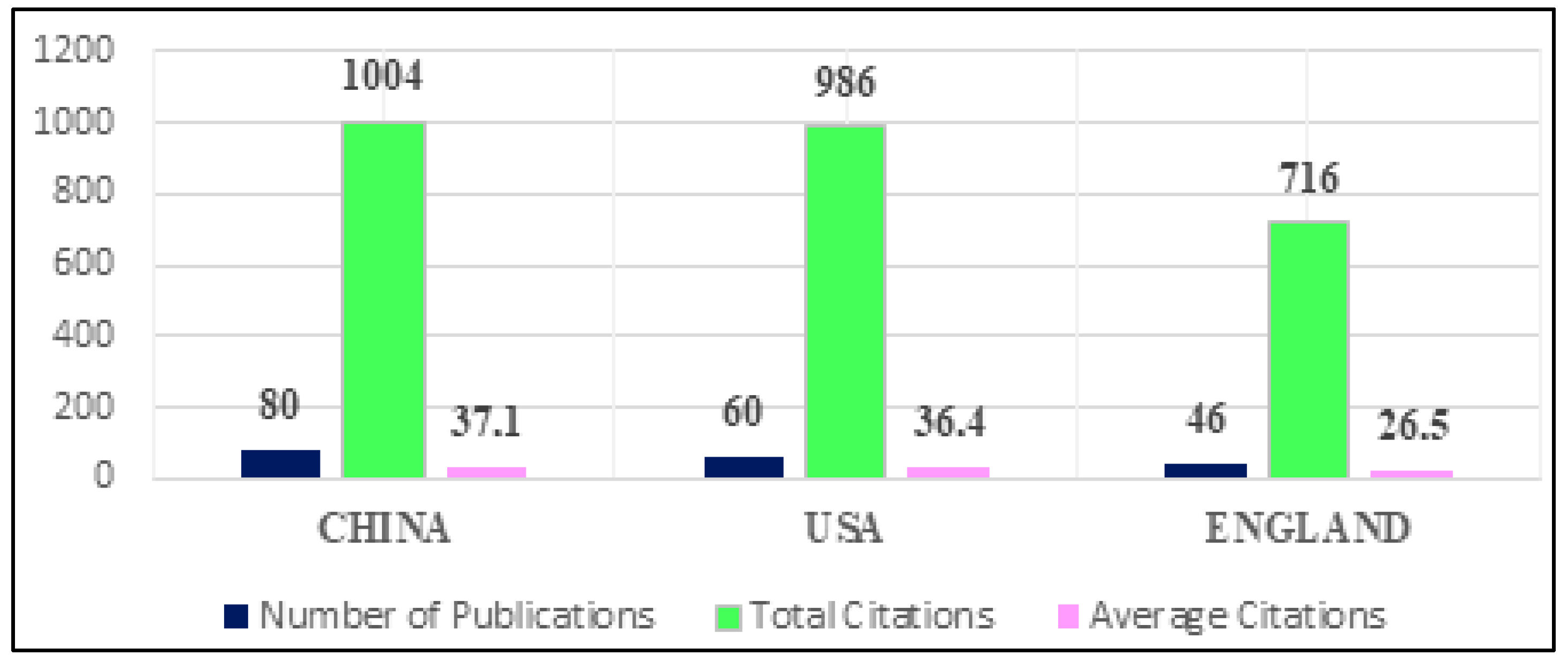

Most Productive Countries/Regions

3.3.2. Bibliometric Network Visualizations

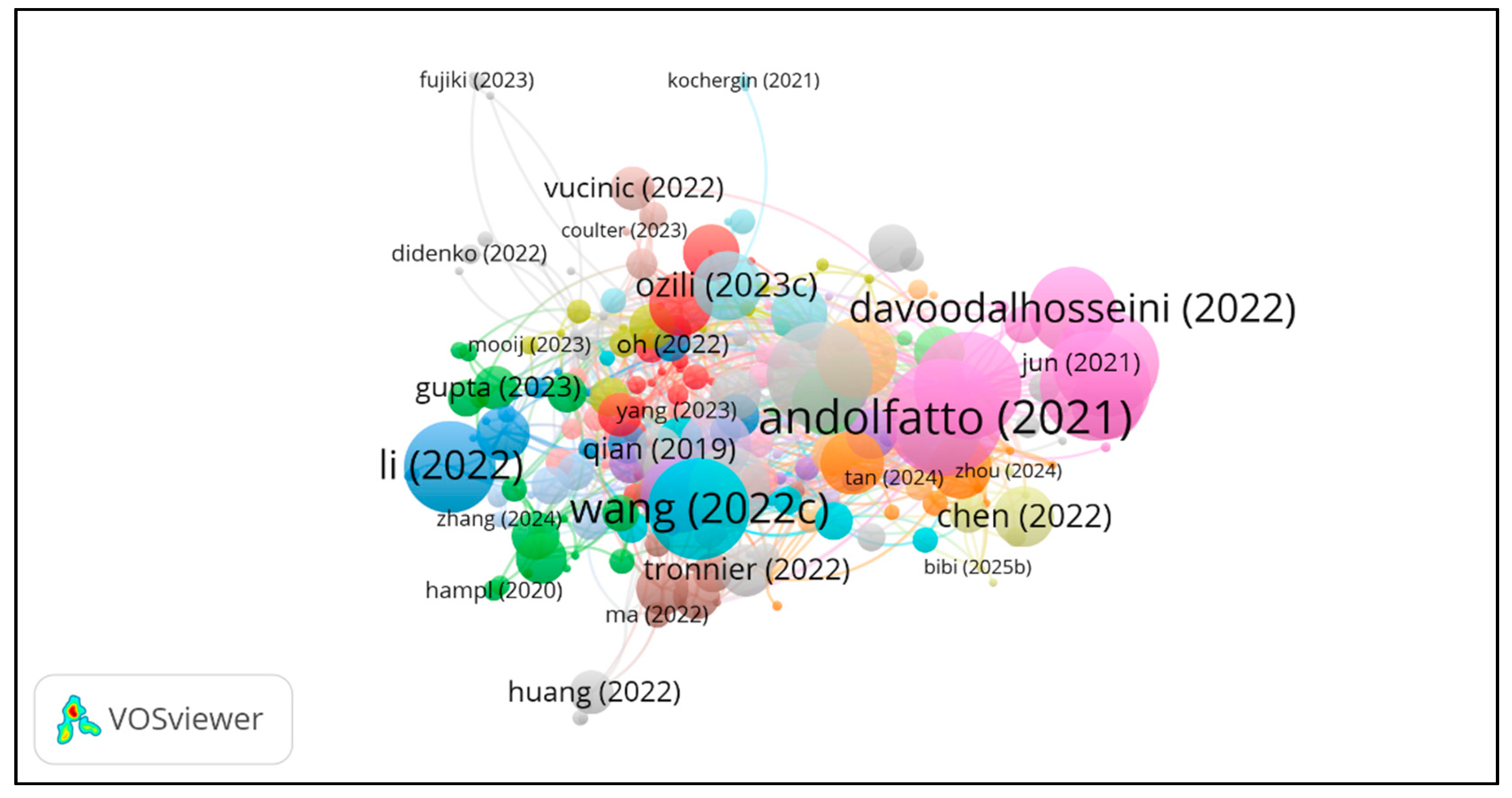

Citation Analysis

Bibliometric Coupling Analysis

Co-Citation Analysis

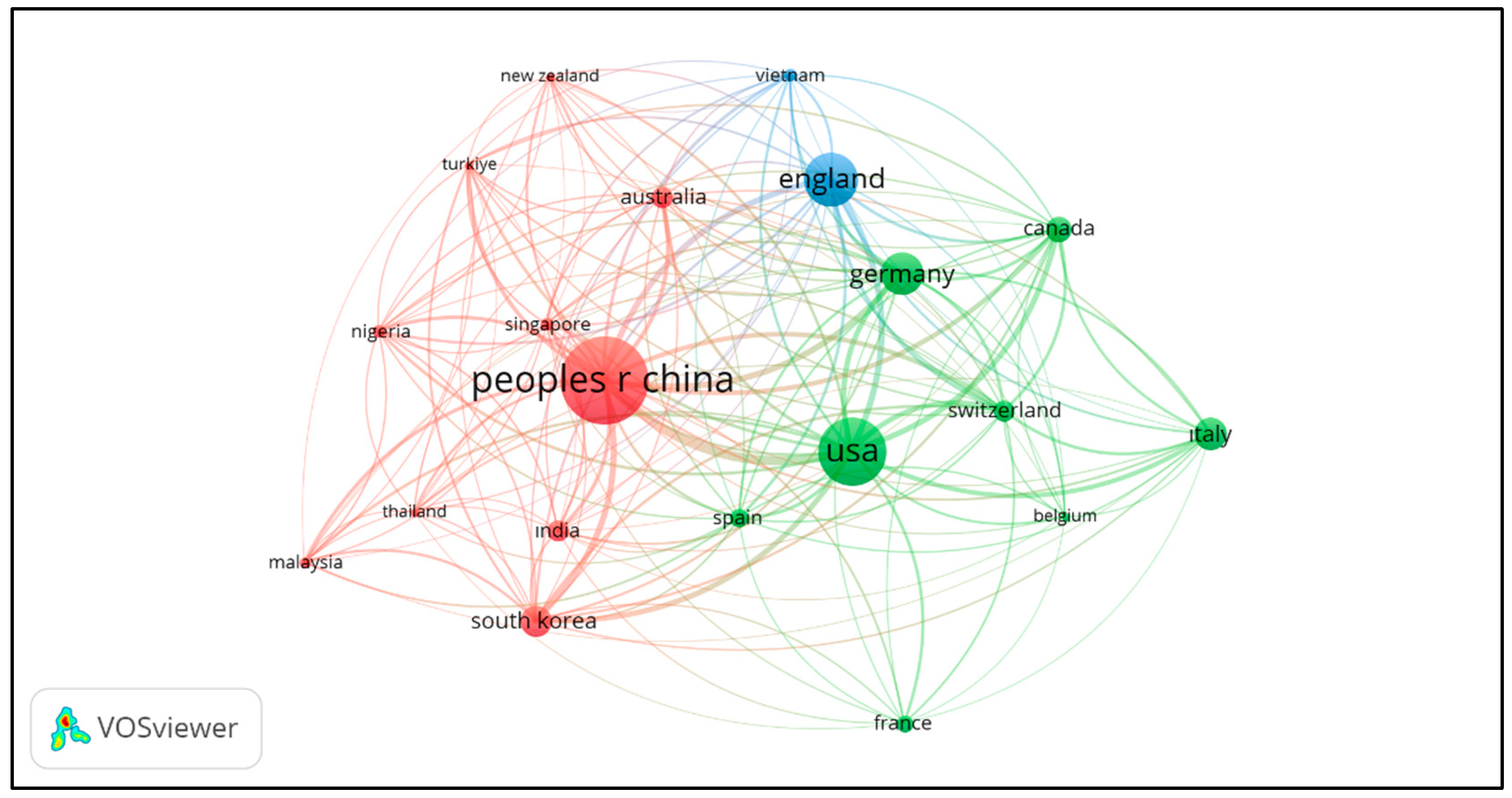

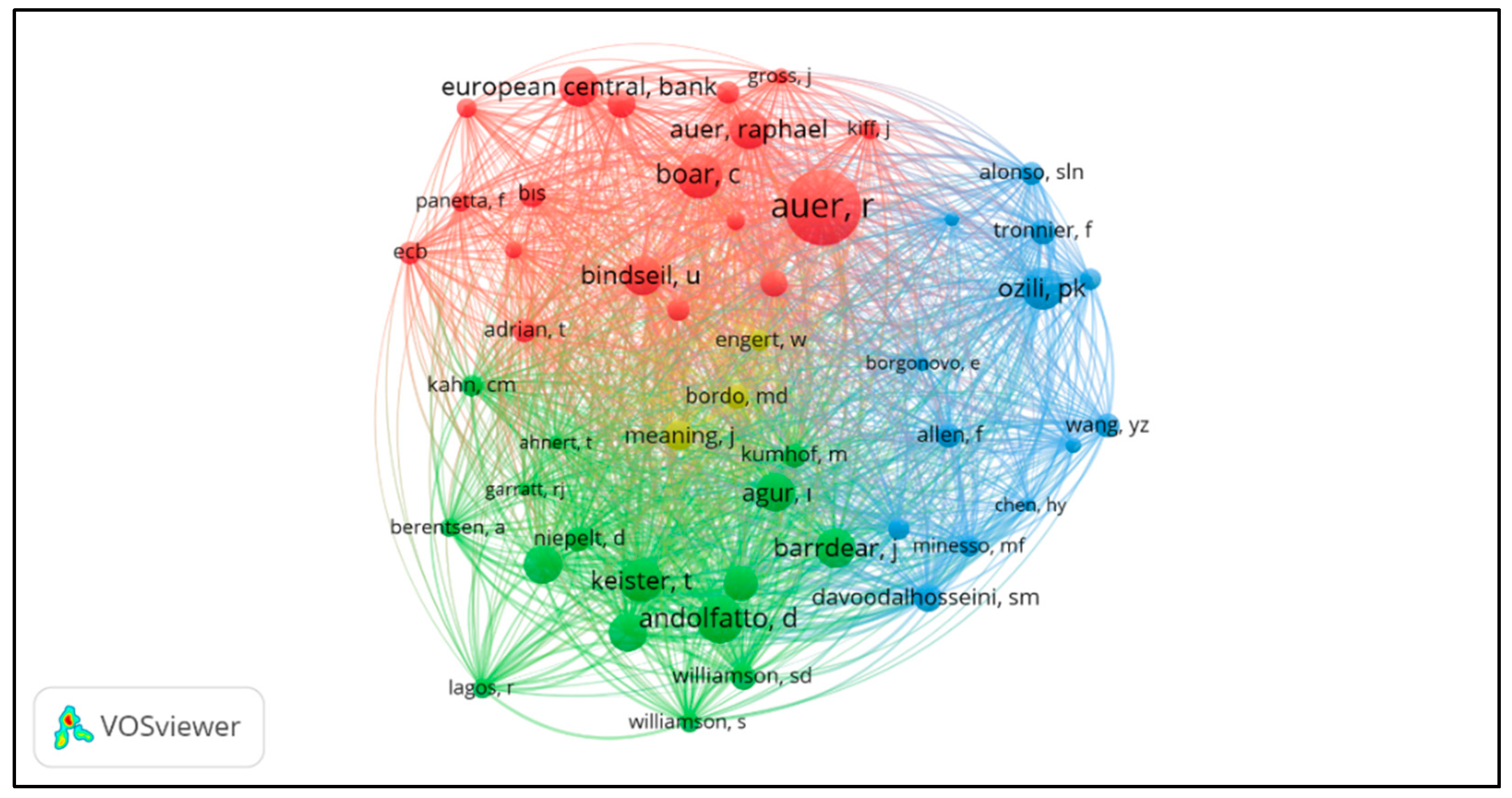

Co-Authorship Analysis

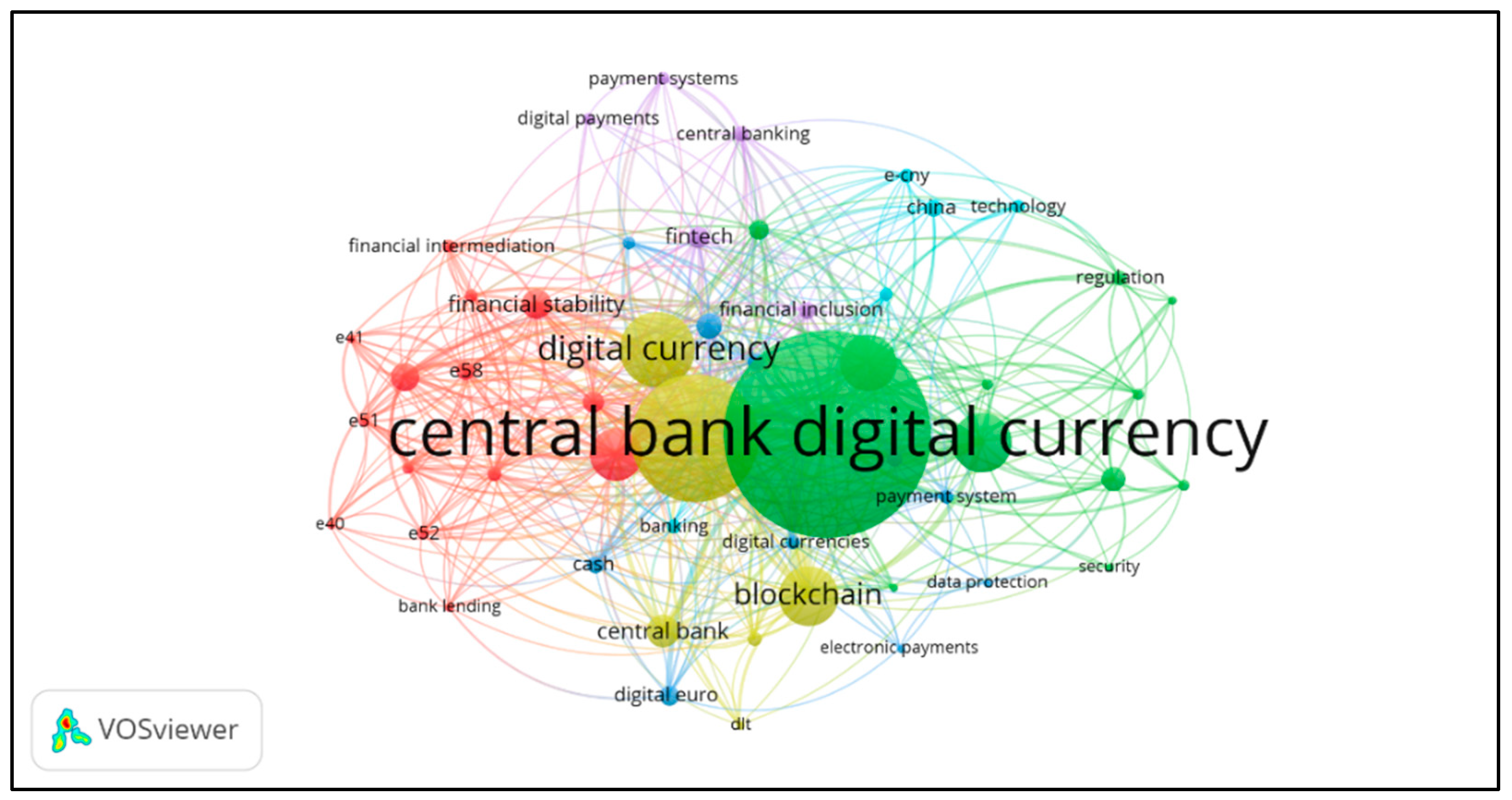

Keyword Analysis

3.3.3. Results of the Content Analysis

Two Case Models

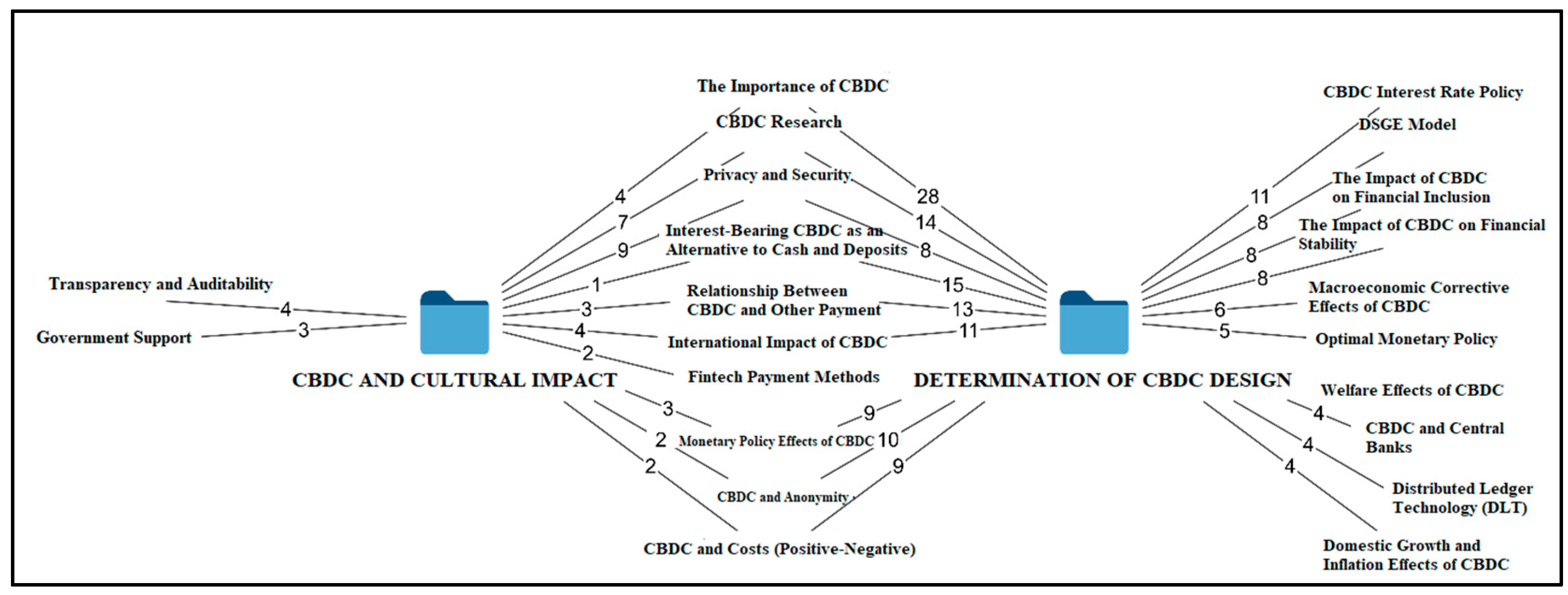

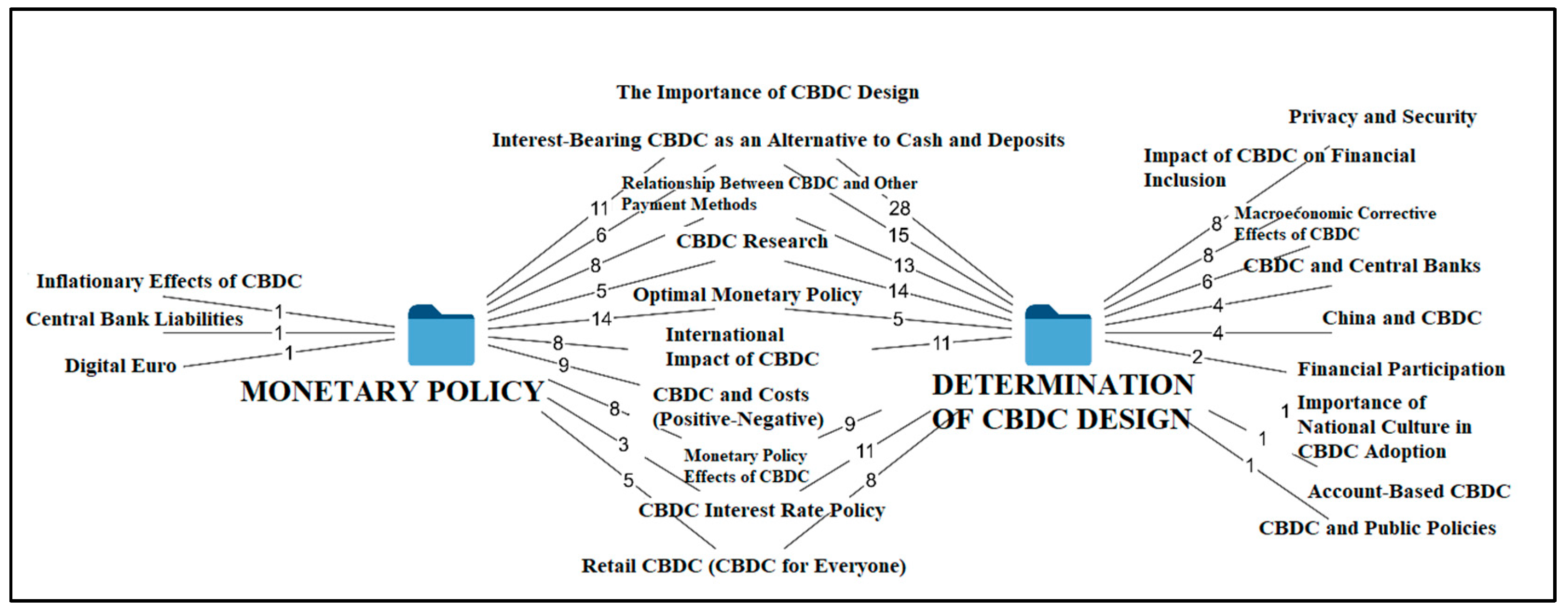

Code Distribution Model

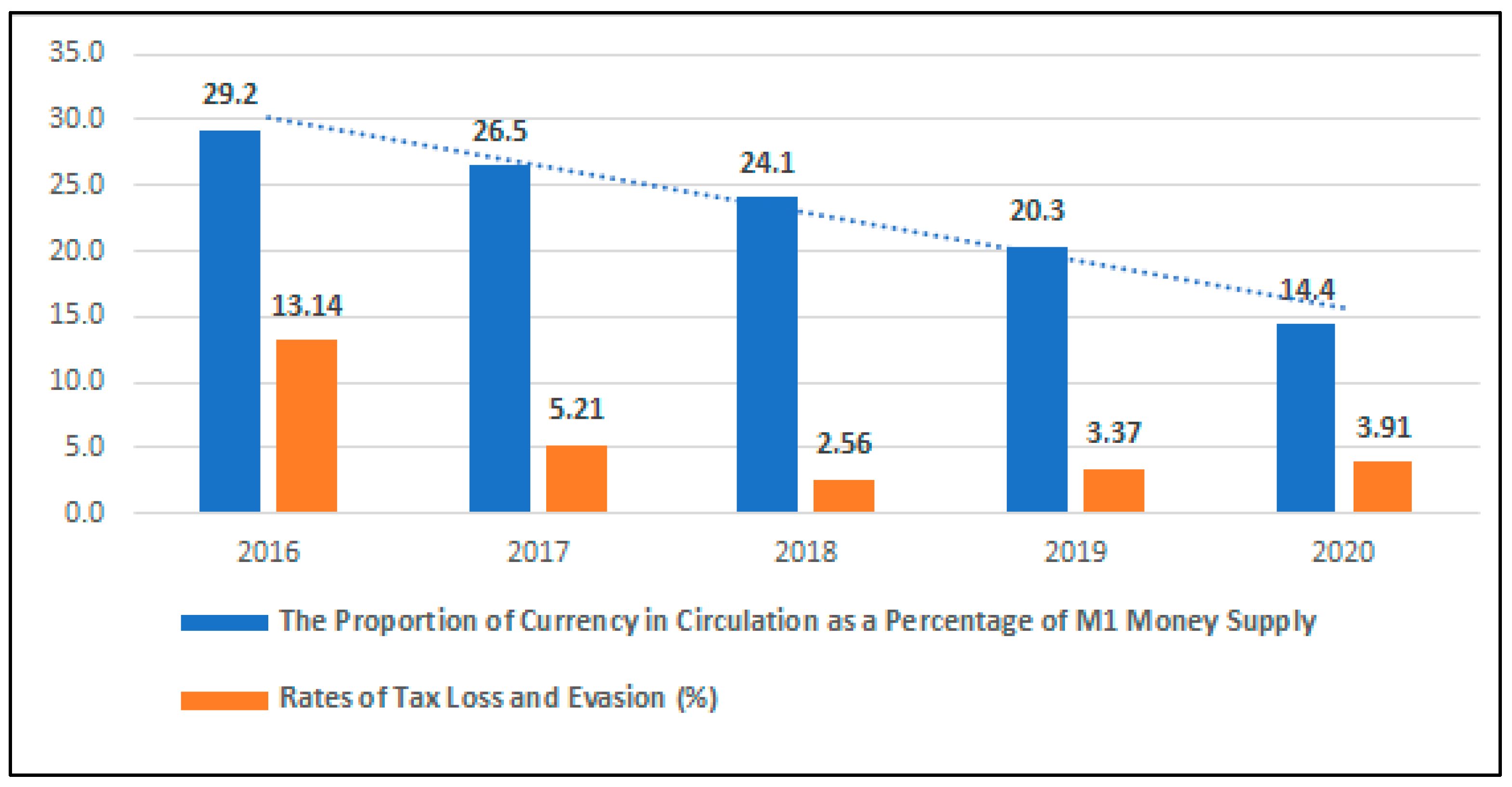

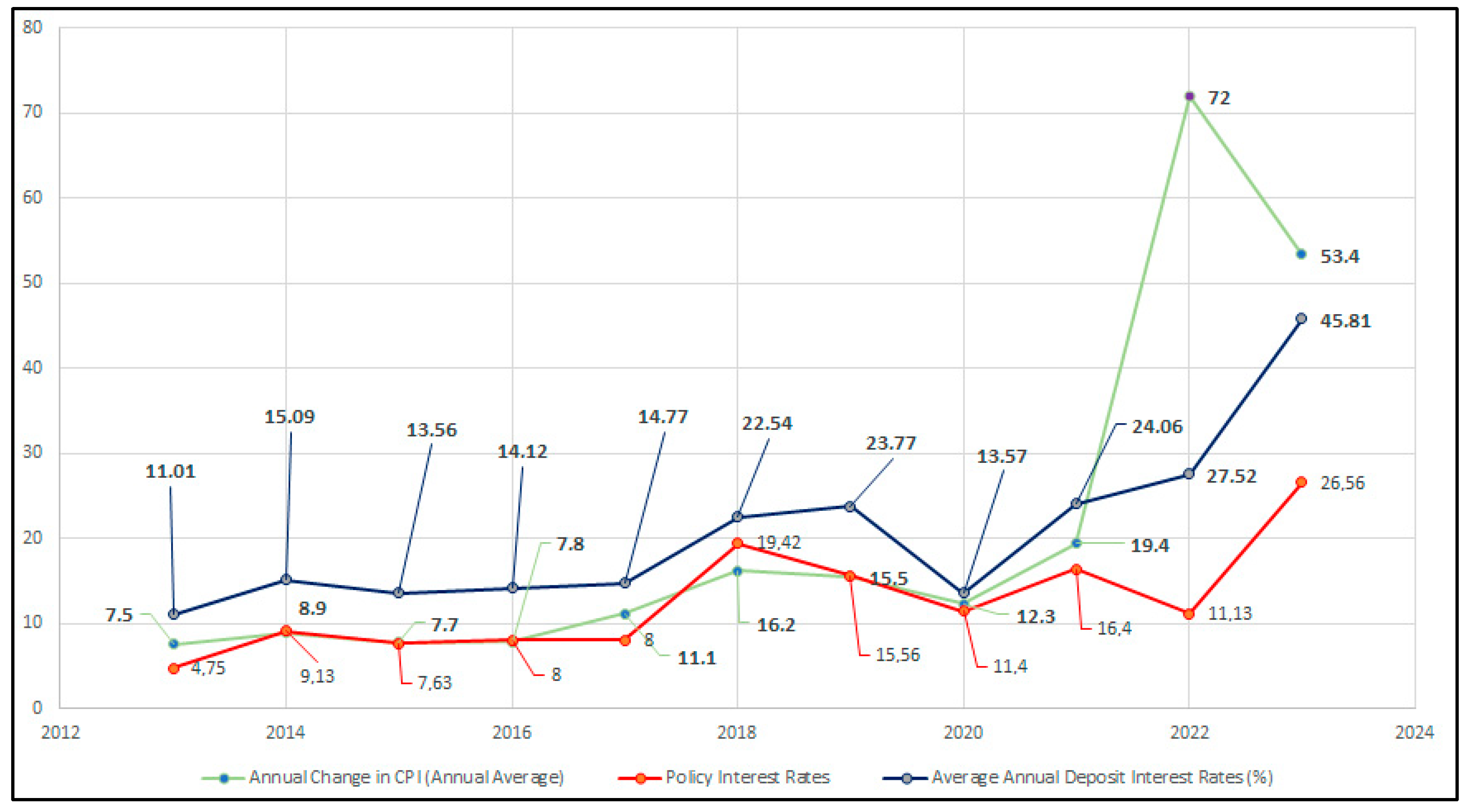

3.3.4. Evaluation of Analysis Results in the Context of Türkiye’s Fiscal Structure

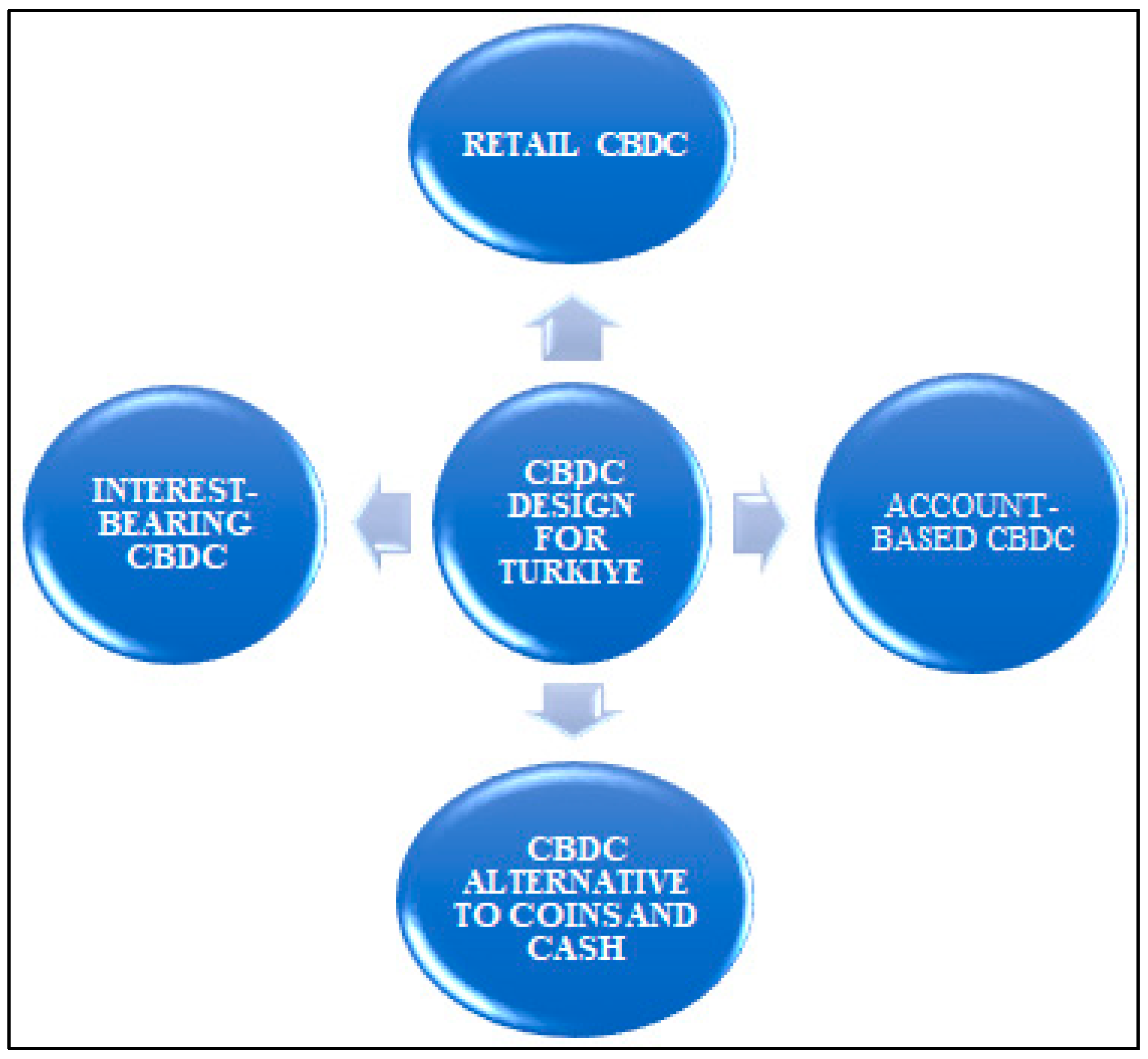

3.4. Proposed CBDC Design for Turkey Based on Analysis Results

- Account-Based CBDC: This system verifies the identity of account holders, aiming to prevent electronic fraud and accurately define relationships between transactions. Under the guarantee of the Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye (CBRT), users will transfer their trust in the Turkish Lira to the CBDC, thereby ensuring the privacy and security of accounts.

- CBDC as an Alternative to Coins and Cash: To address the issue of the informal economy in Türkiye, a CBDC to be used via electronic wallets instead of cash is proposed. This system can monitor transactions, reduce tax loss and evasion, and enhance the effectiveness of fiscal policy.

- Retail CBDC: It is proposed that individuals and firms have direct access to CBDC through CBRT. This model reduces transaction costs, allows the central authority to directly monitor transactions, and ensures centralized control through the use of traditional central bank monetary infrastructure.

- Interest-Bearing CBDC: An interest-bearing CBDC indexed to global interest rates and Türkiye’s policy rate can prevent dollarization and function as an effective medium of exchange and store of value. Additionally, an interest-bearing CBDC enhances price stability, improves the effectiveness of monetary policy, and prevents destabilizing banks from undermining financial stability. For cryptocurrency users, an interest-bearing CBDC offers an attractive, yield-generating alternative.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Abramova, S., Böhme, R., Elsinger, H., Stix, H., & Summer, M. (2022). What can CBDC designers learn from asking potential users? Results from a survey of Austrian residents (Working Paper No: 241). Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/264833 (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Agur, I., Ari, A., & Dell’Ariccia, G. (2022). Designing central bank digital currencies. Journal of Monetary Economics, 125, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahnert, T., Hoffmann, P., Leonello, A., & Porcellacchia, D. (2023). CBDC and financial stability (ECB Working Paper No: 2023/2783). Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4360818 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Andolfatto, D. (2021). Assessing the impact of central bank digital currency on private banks. Economic Journal, 131(634), 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, R., Frost, J., Gambacorta, L., Monnet, C., Rice, T., & Shin, H. S. (2022). Central bank digital currencies: Motives, economic implications, and the research frontier. The Annual Review of Economics, 14, 697–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank for International Settlements. (2020). Annual economic report 2020: Central banks and payments in the digital era. BIS. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2020e3.htm (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Barrdear, J., & Kumhof, M. (2022). The macroeconomics of central bank digital currencies. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 142, 104148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bindseil, U. (2019). Central bank digital currency: Financial system implications and control. International Journal of Political Economy, 48(4), 303–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L., & Mutz, R. (2015). Growth rates of modern science: A bibliometric analysis based on the number of publications and cited references. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(11), 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunnermeier, M. K., James, H., & Landau, J. P. (2019). The digitalization of money (No. w26300). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Carapella, F. (2022). Discussion of “Central bank digital currency and flight to safety”. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 142, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CashEssentials. (2021). Cash and digital payments after the COVID-19 pandemic. CashEssentials. Available online: https://cashessentials.org/publication/cash-and-digital-payments-after-the-covid-19-pandemic/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Cavanagh, S. (1997). Content analysis: Concepts, methods and applications. Nurse Researcher, 4(3), 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CBRT. (2024). Merkez bankası faiz oranları. Available online: https://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/tr/tcmb+tr/main+menu/temel+faaliyetler/para+politikasi/merkez+bankasi+faiz+oranlari (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Chen, H., & Siklos, P. L. (2022). Central bank digital currency: A review and some macro-financial implications. Journal of Financial Stability, 60, 100985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J., Davoodalhosseini, S. M., Jiang, J., & Zhu, Y. (2023). Bank market power and central bank digital currency: Theory and quantitative assessment. Journal of Political Economy, 131(5), 1213–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2000). Research methods in education. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Copestake, A., Furceri, D., & Gonzalez-Dominguez, P. (2023). Crypto market responses to digital asset policies. Economics Letters, 222, 110949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukierman, A. (2019). Welfare and political economy aspects of a central bank digital currency. Alex Cukierman. [Google Scholar]

- Çalık, M., & Sözbilir, M. (2014). İçerik analizinin parametreleri. Eğitim ve Bilim, 39(174), 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Bianco, S. (2020). Central bank digital currency: Aims, mechanisms and macroeconomic impact. In The economics of cryptocurrencies (pp. 77–82). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Davoodalhosseini, S. M. (2022). Central bank digital currency and monetary policy. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 142, 104150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bakker, F. G., Groenewegen, P., & Den Hond, F. (2005). A bibliometric analysis of 30 years of research and theory on corporate social responsibility and corporate social performance. Business & Society, 44(3), 283–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinçer, S. (2018). Content analysis in scientific research: Meta-analysis, meta-synthesis, and descriptive content analysis. Bartın Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 7(1), 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionysopoulos, L., Marra, M., & Urquhart, A. (2024). Central bank digital currencies: A critical review. International Review of Financial Analysis, 91, 103031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enajero, S. (2021). Cryptocurrency, money demand and the mundell-fleming model of international capital mobility. Atlantic Economic Journal, 49(1), 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S., & Bulut, M. (2024). Central bank digital currencies: A comprehensive systematic literature review on worldwide research emergence and methods used. American Journal of Business, 39(3), 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimnia, B., Sarkis, J., & Davarzani, H. (2015). Green supply chain management: A review and bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Production Economics, 162, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegatelli, P. (2022). A central bank digital currency in a heterogeneous monetary union: Managing the effects on the bank lending channel. Journal of Macroeconomics, 71, 103392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Villaverde, J., Sanches, D., Schilling, L., & Uhlig, H. (2021). Central bank digital currency: Central banking for all? Review of Economic Dynamics, 41, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. (2014). An introduction to qualitative research. Torrossa. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki, H. (2023). Attributes needed for Japan’s central bank digital currency. The Japanese Economic Review, 74(1), 117–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiki, H. (2024). Central bank digital currency, crypto assets, and cash demand: Evidence from Japan. Applied Economics, 56(19), 2241–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerçek, A., & Uygun, E. (2022). Türkiye’de vergi kayip ve kaçaklarinin vergi türlerine göre hesaplanmasi ve değerlendirilmesi (2005–2020 yillari). Vergi Raporu, 268, 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- GİB. (2024). Vergi istatistikleri. Available online: https://www.gib.gov.tr/kurumsal/planlar-ve-raporlar/istatistikler (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Glenn, N., & Reed, R. (2024). Cryptocurrency, security, and financial intermediation. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 56(1), 185–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glesne, C., & Peshkin. (1992). Becaoming qualitative researchers: An introduction. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, K. P., Molnar, J., Shcherbakov, O., & Yu, Q. (2020). Demand for payment services and consumer welfare: The introduction of a central bank digital currency. Available online: https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2020/03/staff-working-paper-2020-7/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Jacobs, B. (2017). Digitalization and taxation. In Digital revolutions in public finance. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. S., & Kwon, O. (2023). Central bank digital currency, credit supply, and financial stability. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 55(1), 297–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kumhof, M., & Noone, C. (2021). Central bank digital currencies—Design principles for financial stability. Economic Analysis and Policy, 71, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O., Lee, S., & Park, J. (2020). Central bank digital currency, tax evasion, inflation tax, and central bank independence. Economic Research Institute, Bank of Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, O., Lee, S., & Park, J. (2022). Central bank digital currency, tax evasion, and inflation tax. Economic Inquiry, 60(4), 1497–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawani, S. M. (1981). Bibliometrics: Its theoretical foundations, methods and applications. Libri, 31, 294–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. K. C., Yan, L., & Wang, Y. (2021). A global perspective on central bank digital currency. China Economic Journal, 14(1), 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. D., Tran, S. H., Nguyen, D. T., & Ngo, T. (2023). The degrees of central bank digital currency adoption across countries: A preliminary analysis. Economics and Business Letters, 12(2), 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. (2023). Predicting the demand for central bank digital currency: A structural analysis with survey data. Journal of Monetary Economics, 134, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., & Huang, Y. (2021). The genesis, design and implications of China’s central bank digital currency. China Economic Journal, 14(1), 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, H. N., Do, D. D., Pham, T., Ho, V. X., & Dinh, Q. A. (2023). Cultural values and the adoption of central bank digital currency. Applied Economics Letters, 30(15), 2024–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magin, J., Neyer, U., & Stempel, D. (2023). The macroeconomic effects of different CBDC regimes in an economy with a heterogeneous household sector. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/277656 (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Mancini-Griffoli, T., Soledad Martinez Peria, M., Agur, I., Ari, A., Kiff, J., Popescu, A., & Rochon, C. (2018). Casting light on central bank digital currency. Staff Discussion Notes, 18(8), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2014). Designing qualitative research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Minesso, M. F., Mehl, A., & Stracca, L. (2022). Central bank digital currency in an open economy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 127, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, C., & Keister, T. (2022). Central bank digital currency: Stability and information (Working Paper No. 22.03). Swiss National Bank, Study Center Gerzensee.

- Morgan, J. (2023). Systemic stablecoin and the brave new world of digital money. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 47(1), 215–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, D. (2014). Qualitative research in educational communications and technology: A brief introduction to principles and procedures. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 26(1), 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niepelt, D. (2020). Monetary policy with reserves and CBDC: Optimality, equivalence, and politics. Available online: www.cepr.org (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Oh, E. Y., & Zhang, S. (2022). Informal economy and central bank digital currency. Economic Inquiry, 60(4), 1520–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osareh, F. (1996). Bibliometrics, citation analysis and co-citation analysis: A review of literatüre I. Libri, 46, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruffo, L., Cunha, A. M., & Ferrari Haines, A. E. (2023). China’s central bank digital currency (CBDC): An assessment of money and power relations. New Political Economy, 28(6), 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidency of Strategy and Budget. (2024). The medium term program 2025–2027. Available online: https://www.sbb.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Medium_Term_Program_2025-2027-11102024.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Pritchard, A. (1969). Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics? Journal of Documentation, 25(4), 348–349. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Y. (2019). Central Bank Digital Currency: Optimization of the currency system and its issuance design. China Economic Journal, 12(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rädiker, S., & Kuckartz, U. (2020). Focused analysis of qualitative interviews with MAXQDA. MAXQDA Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, D., Guo, H., & Jiang, T. (2023). Managed anonymity of CBDC, social welfare and taxation: A new monetarist perspective. Applied Economics, 55(42), 4990–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Breu, M. (2022). Discussion of “Central bank digital currency and monetary policy”. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 142, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, K., Dayanandan, A., & Kuntluru, S. (2023). India’s CBDC for digital public infrastructure. Economics Letters, 231, 111302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarcella, L. (2021). The implications of adopting a European central bank digital currency: A tax policy perspective. EC Tax Review, 30(4), 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5(4), 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., Sangari, M. S., & Mashatan, A. (2025). Adoption of central bank digital currencies: A data-driven exploration of key influential factors. Association for Information Systems (AIS) eLibrary. [Google Scholar]

- Siu, R. C. (2023). Social, political, and economic dimensions of the instituted process of central bank digital currency: The case of the digital yuan. Journal of Economic Issues, 57(2), 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, H., & Clarke, D. (2009). Advancements in research synthesis methods: From a methodologically inclusive perspective. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 395–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tercero-Lucas, D. (2023). Central bank digital currencies and financial stability in a modern monetary system. Journal of Financial Stability, 69, 101188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, J. (1958). Estimation of relationships for limited dependent variables. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 26, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W., & Jiayou, C. (2021). A study of the economic impact of central bank digital currency under global competition. China Economic Journal, 14(1), 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, S. (2022). Comment on “Developments and implications of central bank digital currency: The case of China e-CNY”. Asian Economic Policy Review, 17(2), 253–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ültay, E., Akyurt, H., & Ültay, N. (2021). Sosyal bilimlerde betimsel içerik analizi. IBAD Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 10, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oordt, M. R. (2022). Discussion of “Central bank digital currency: Stability and information”. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 142, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, A. (2018). The pros and cons of issuing a central bank digital currency. Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bulletin, Reserve Bank of New Zealand, 81, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, C. A. (2022). Discussion of “designing central bank digital currency” by Agur, Ari and Dell’Ariccia. Journal of Monetary Economics, 125, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, S. (2022). Central bank digital currency: Welfare and policy implications. Journal of Political Economy, 130(11), 2829–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, S. D. (2022). Central bank digital currency and flight to safety. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 142, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2022, June 29). COVID-19 drives global surge in use of digital payments. World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/06/29/covid-19-drives-global-surge-in-use-of-digital-payments (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Xin, B., & Jiang, K. (2023). Economic uncertainty, central bank digital currency, and negative interest rate policy. Journal of Management Science and Engineering, 8(4), 430–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. (2022). Developments and implications of central bank digital currency: The case of China e-CNY. Asian Economic Policy Review, 17(2), 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q. (2018). A systematic framework to understand central bank digital currency. Science China Information Sciences, 61(3), 033101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I., & Čater, T. (2015). Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organizational Research Methods, 18(3), 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Study | Count | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Article | 336 | 76.7 |

| Early Access | 24 | 5.5 |

| Review Article | 13 | 3.0 |

| Proceeding Paper | 46 | 10.5 |

| Editorial Material | 12 | 2.7 |

| Book Chapter | 7 | 1.6 |

| Total | 438 |

| Codes | Sample Statements | Studies Containing the Statements |

|---|---|---|

| The Importance of CBDC Design | For a CBDC to gain widespread acceptance, it must possess features that encourage people to feel willing to use it, including user-friendliness. | Comment on “Developments and Implications of Central Bank Digital Currency: The Case of China e-CNY |

| Effects of CBDC on Banking Operations (Stability-Intermediation-Disintermediation) | The implementation of a CBDC can turn depositors’ withdrawal decisions into strategic substitutions, thereby eliminating the typical equilibrium multiplicity observed in such models. In these cases, the introduction of a CBDC clearly enhances the stability of the banking system. | Central bank digital currency: Stability and information |

| Interest-Bearing CBDC as an Alternative to Cash and Deposits | CBDC serves as an excellent alternative to deposits in terms of payment functions and carries an interest rate set by the central bank. | Bank Market Power and Central Bank Digital Currency: Theory and Quantitative Assessment |

| Codes | Documents | Percentage | Coded Sections of All Documents |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Importance of CBDC Design | 25 | 62.50 | 70 |

| The Effects of CBDC on Banking Operations (Stability-Intermediation-Disintermediation) | 23 | 57.50 | 56 |

| Interest-Bearing CBDC as an Alternative to Cash and Deposits | 20 | 50.00 | 44 |

| CBDC Research | 25 | 62.50 | 41 |

| Optimal Monetary Policy | 15 | 37.50 | 39 |

| Relationship Between CBDC and Other Payment Methods | 23 | 57.50 | 36 |

| CBDC Interest Rate Policy | 13 | 32.50 | 35 |

| Retail CBDC (CBDC for Everyone) | 20 | 50.00 | 33 |

| CBDC and Costs (Positive-Negative) | 15 | 37.50 | 31 |

| Privacy and Security | 17 | 42.50 | 30 |

| Welfare Effects of CBDC | 15 | 37.50 | 27 |

| Monetary Policy Effects of CBDC | 16 | 40.00 | 27 |

| Fintech Payment Methods | 15 | 37.50 | 24 |

| International Impact of CBDC | 8 | 20.00 | 23 |

| Bank Panics, Failures, and CBDC | 6 | 15.00 | 22 |

| CBDC and Anonymity | 11 | 27.50 | 21 |

| Relationship Between CBDC and Informal Economy | 12 | 30.00 | 42 |

| Optimal Interest Rate Policy | 10 | 25.00 | 20 |

| DSGE Model | 7 | 17.50 | 16 |

| Digitalization and Technological Innovations | 15 | 37.50 | 16 |

| Factors Affecting CBDC Adoption (Incentives-Information) | 11 | 27.50 | 18 |

| Impact of CBDC on Tax Policies | 7 | 17.50 | 12 |

| CBDC’s Role in Preventing Tax Loss and Evasion | 6 | 15.00 | 12 |

| CBDC and Central Banks | 7 | 17.50 | 11 |

| Macroeconomic Stability | 7 | 17.50 | 11 |

| Liquidity Feature of CBDC | 7 | 17.50 | 11 |

| Inflationary Effects of CBDC | 5 | 12.50 | 11 |

| Central Bank Liabilities | 7 | 17.50 | 11 |

| Importance of National Culture in CBDC Adoption | 3 | 7.50 | 11 |

| Macroeconomic Corrective Effects of CBDC | 6 | 15.00 | 10 |

| Optimal Consumption, Savings, and Investment Preferences under CBDC | 8 | 20.00 | 9 |

| CBDC and Optimal Policy Effects | 5 | 12.50 | 9 |

| Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) | 7 | 17.50 | 8 |

| Digitalization of Money | 6 | 15.00 | 7 |

| Domestic Growth and Inflation Effects of CBDC | 3 | 7.50 | 6 |

| China’s CBDC | 4 | 10.00 | 6 |

| Digital Euro | 3 | 7.50 | 5 |

| Asymmetry in the Monetary System | 3 | 7.50 | 5 |

| Wholesale CBDC | 4 | 10.00 | 4 |

| Account-Based CBDC | 3 | 7.50 | 4 |

| Transparency and Auditability | 1 | 2.50 | 4 |

| Government Support | 1 | 2.50 | 3 |

| CBDC and Public Policies | 2 | 5.00 | 2 |

| CBDC and Financial Architecture | 27 | 67.50 | 0 (Main Code) |

| Analyzed Documents | 40 | 100.00 | 929 |

| Objectives | Studies | % | f |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensuring the Effectiveness of Monetary Policy |

| 13.56 | 126 |

| Ensuring Financial Stability in the Economy |

| 16.58 | 154 |

| Examining the Effects of CBDC on the Banking Sector and Providing Recommendations |

| 19.80 | 184 |

| The examination of the impact of CBDC on preventing the informal economy and the harmonization of tax policies |

| 15.18 | 141 |

| An Examination of the Design Characteristics and Types of CBDCs in Order to Determine the Most Suitable Technology |

| 26.59 | 247 |

| Examination of the Adaptation of CBDC to the Cultural Structures of Nations |

| 8.29 | 77 |

| Studies | Theoretical Studies | Empirical Studies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | India’s CBDC for digital public infrastructure, Sandhu et al. (2023) | (+) | |

| 2 | Cultural values and the adoption of central bank digital currency, Luu et al. (2023) | (+) | |

| 3 | China’s central bank digital currency (CBDC): an assessment of money and power relations, Peruffo et al. (2023) | (+) | |

| 4 | Comment on “Developments and Implications of Central Bank Digital Currency: The Case of China e-CNY”, Uchida (2022). | (+) | |

| 5 | Developments and Implications of Central Bank Digital Currency: The Case of China e-CNY, Xu (2022). | (+) | |

| 6 | Social, Political, and Economic Dimensions of the Instituted Process of Central Bank Digital Currency: The Case of the Digital Yuan, Siu (2023). | (+) | |

| 7 | The genesis, design and implications of China’s central bank digital currency, S. Li and Huang (2021). | (+) | |

| 8 | Central bank digital currency: Aims, mechanisms and macroeconomic impact, Dal Bianco (2020). | (+) | |

| 9 | Attributes needed for Japan’s central bank digital currency, Fujiki (2023). | (+) | |

| 10 | Discussion of “designing central bank digital currency” by Agur, Ari and Dell’Ariccia, Wilkins (2022). | (+) | |

| 11 | The macroeconomics of central bank digital currencies, Barrdear and Kumhof (2022). | (+) | |

| 12 | Economic uncertainty, central bank digital currency, and negative interest rate policy, Xin and Jiang (2023). | (+) | |

| 13 | A study of the economic impact of central bank digital currency under global competition, Tong and Jiayou (2021). | (+) | |

| 14 | A Global perspective on central bank digital currency, D. K. C. Lee et al. (2021). | (+) | |

| 15 | Central bank digital currency, crypto assets, and cash demand: evidence from Japan, Fujiki (2024). | (+) | |

| 16 | Predicting the demand for central bank digital currency: A structural analysis with survey data, J. Li (2023). | (+) | |

| 17 | Crypto market responses to digital asset policies, Copestake et al. (2023). | (+) | |

| 18 | Informal economy and central bank digital currency, Oh and Zhang (2022). | (+) | |

| 19 | Central Bank Digital Currency: Welfare and Policy Implications, S. Williamson (2022). | (+) | |

| 20 | Central bank digital currency, tax evasion, and inflation tax, Kwon et al. (2020). | (+) | |

| 21 | The degrees of central bank digital currency adoption across countries: A preliminary analysis, T. D. Lee et al. (2023). | (+) | |

| 22 | Discussion of “Central bank digital currency and flight to safety”, Carapella (2022). | (+) | |

| 23 | Bank Market Power and Central Bank Digital Currency: Theory and Quantitative Assessment, Chiu et al. (2023). | (+) | |

| 24 | Central bank digital currency and flight to safety, S. D. Williamson (2022). | (+) | |

| 25 | Central bank digital currency: Stability and information, Monnet and Keister (2022). | (+) | |

| 26 | Assessing the Impact of Central Bank Digital Currency on Private Banks, Andolfatto (2021). | (+) | |

| 27 | Cryptocurrency, Security, and Financial Intermediation, Glenn and Reed (2024). | (+) | |

| 28 | Central Bank Digital Currency: Financial System Implications and Control, Bindseil (2019). | (+) | |

| 29 | Central bank digital currency: Central banking for all? Fernández-Villaverde et al. (2021). | (+) | |

| 30 | Central bank digital currency: A review and some macro-financial implications, Chen and Siklos (2022). | (+) | |

| 31 | A central bank digital currency in a heterogeneous monetary union: Managing the effects on the bank lending channel, Fegatelli (2022). | (+) | |

| 32 | Discussion of “Central bank digital currency: Stability and information”, van Oordt (2022). | (+) | |

| 33 | Central Bank Digital Currency, Credit Supply, and Financial Stability, Kim and Kwon (2023). | (+) | |

| 34 | Central bank digital currencies: Design principles for financial stability, Kumhof and Noone (2021). | (+) | |

| 35 | Central bank digital currency in an open economy, Minesso et al. (2022). | (+) | |

| 36 | Discussion of “Central bank digital currency and monetary policy”, Rojas-Breu (2022). | (+) | |

| 37 | Central bank digital currency and monetary policy, Davoodalhosseini (2022). | (+) | |

| 38 | Central Bank Digital Currency: optimization of the currency system and its issuance design, Qian (2019). | (+) | |

| 39 | Systemic stablecoin and the brave new world of digital money, Morgan (2023). | (+) | |

| 40 | Reflections on welfare and political economy aspects of a central bank digital currency, Cukierman (2019). | (+) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bilgiç Ulun, A. Bibliometric and Content Analysis on Central Bank Digital Currencies for the Period 2018–2025 and a Policy Model Proposal for Türkiye. Economies 2025, 13, 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100303

Bilgiç Ulun A. Bibliometric and Content Analysis on Central Bank Digital Currencies for the Period 2018–2025 and a Policy Model Proposal for Türkiye. Economies. 2025; 13(10):303. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100303

Chicago/Turabian StyleBilgiç Ulun, Ayşegül. 2025. "Bibliometric and Content Analysis on Central Bank Digital Currencies for the Period 2018–2025 and a Policy Model Proposal for Türkiye" Economies 13, no. 10: 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100303

APA StyleBilgiç Ulun, A. (2025). Bibliometric and Content Analysis on Central Bank Digital Currencies for the Period 2018–2025 and a Policy Model Proposal for Türkiye. Economies, 13(10), 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100303