1. Introduction

The innovation economy has become a central paradigm for global economic growth, with startups serving as a critical component of this ecosystem. Startups play a pivotal role in driving technological advancements and contributing to societal well-being. In developing countries, technology-driven startups are increasingly significant as catalysts for economic and social development, delivering innovative products and services that propel societal progress.

In emerging economies, startups act as accelerators of development, prompting policymakers to strengthen entrepreneurial ecosystems through targeted policies. Yet these ecosystems face numerous uncertainties and risks, including gaps in investment, weak legal and institutional frameworks, and technological barriers that constrain scalability. Such systemic issues are especially visible in technology-driven ecosystems, where scaling innovative products requires consistent regulation and robust infrastructure. Emerging ventures—whether pursuing frugal or digital innovation—also encounter challenges such as resource constraints, ethical concerns, and policy gaps, highlighting the need for collaborative, equity-focused approaches to ensure entrepreneurship contributes to sustainable and inclusive development (

Dote-Pardo et al., 2025).

Prior research on the growth of startups in emerging economies has identified critical barriers, including insufficient policy support, difficulties in transitioning from early-stage to scale-up phases, inconsistent regulatory frameworks, weak infrastructure, and limited access to growth finance (

Pardo-del-Val et al., 2025). These challenges are particularly pronounced in developing nations, where startups operate in precarious conditions. While Iran has developed digital and human capital structures that foster entrepreneurial growth, significant limitations remain (

Jahanbakht & Ahmadi, 2025). Broader comparative evidence shows that many of these obstacles are structural. For example, startup accelerators are disproportionately concentrated in the United States, pushing many entrepreneurs from developing regions to emigrate in order to pursue product innovation (

Moroz et al., 2024). At the same time, the rise of generative AI raises concerns of “data colonialism,” whereby as much as 70% of the projected USD 1.7 trillion value of AI-developed products over the next decade may be captured by the United States and China, due to global asymmetries in data ownership and value creation (

Harari, 2024). For countries such as Iran, attracting investment capital therefore requires policies that build domestic capital funding and support structures, an especially difficult task given persistent political, legal, and cultural barriers.

Beyond firm-level hurdles, developing-country ecosystems face additional policy challenges. Persistent credit gaps and collateral requirements constrain early-stage finance, disproportionately affecting new and women-led ventures unless legal frameworks enable lending against movable assets and targeted instruments such as guarantees (

Beck & Demirguc-Kunt, 2006;

World Bank, 2014). Regulatory instability and weak business climates further increase the risk of firm exit, particularly in developing economies where poor institutional quality constrains entrepreneurial survival (

Naudé, 2010). Digital entrepreneurship also requires complementary policies—capability-building, infrastructure, and market access—without which ventures in emerging economies struggle to scale (

Acs et al., 2017). Meta-reviews of entrepreneurship programs highlight that training and credit schemes alone produce uneven results unless embedded in ecosystem-wide reforms (

McKenzie, 2017). Talent dynamics complicate this further: high-skill migration drains local entrepreneurial capacity unless governments foster “brain circulation” through diaspora engagement (

Wescott & Brinkerhoff, 2006). Finally, macro-fiscal constraints, particularly rising debt-service burdens, limit governments’ ability to sustain ecosystem investments (

World Bank, 2023). Together, these findings underscore the importance of context-specific and resilient policy frameworks in fragile entrepreneurial environments. While these challenges are broadly relevant across many developing economies, this study focuses specifically on Iran as a case study to illustrate how such dynamics materialize in practice.

A persistent challenge in developing countries is the lack of reliable and consistent data on entrepreneurial ecosystems, which hampers evidence-based policymaking. This scarcity also makes local data vulnerable to extraction and commoditization by external actors.

Harari (

2024) has warned of “data colonialism,” in which global asymmetries allow advanced economies to capture disproportionate value from AI-driven innovation. Recent evidence further shows that Chinese firms have engaged in predatory data extraction practices across Africa and Asia, with limited reinvestment in local ecosystems (

Travers, 2024;

Heeks et al., 2024). Such dynamics underscore that government policy is not only about filling domestic information gaps but also about ensuring data sovereignty and anchoring spillover benefits within the local ecosystem. The advent of big data and artificial intelligence offers new ways to bridge these information gaps and enable data-driven policy design. In particular, news media provide one of the few systematic and timely windows into entrepreneurial activity and policy debates in data-scarce environments. Prior studies demonstrate the value of analyzing news coverage as a proxy for policy and economic signals. For instance,

Azqueta-Gavaldón (

2017) used topic modeling to extract policy-related themes from U.S. newspapers. Similar methodologies are increasingly applied in emerging economy contexts, where news serves as a critical proxy for real-time ecosystem dynamics. We acknowledge, however, that news outlets may reflect editorial biases, censorship, or changing reporting practices, which can shape coverage in ways that are not purely reflective of ecosystem dynamics. To mitigate these risks, our approach incorporated source diversity, the deduplication of overlapping articles, and sensitivity checks across outlet subsets. These steps help reduce, though cannot fully eliminate, potential distortions—an issue further discussed in the

Section 7.

Iran provides a compelling case for investigation due to its notable progress in technology-based entrepreneurship, which has stimulated job creation and economic diversification. A highly skilled ICT workforce, cultivated through a robust university system, has shaped the entrepreneurial landscape. Complementing this, supportive policies, technology parks, incubators, and state-backed venture capital initiatives have emerged to strengthen ecosystem infrastructure. Comparable insights from mobile telecommunications firms in other emerging economies show that entrepreneurs often rely on adaptive capabilities to navigate uncertainty and expand regionally (

Jahanbakht et al., 2022). Despite these advances, Iran’s entrepreneurial ecosystem remains constrained by institutional weaknesses and persistent uncertainty—conditions that make it an important and informative case for studying the policy challenges of developing-country ecosystems. It is important to note that a structured search of Persian-language scholarship on entrepreneurship and innovation policy revealed limited peer-reviewed, data-driven research. While government reports and policy briefs exist, systematic analysis is scarce. This gap underscores both the novelty of our study and the contribution of integrating Persian-language sources into broader debates on entrepreneurship ecosystems.

Our analysis applies

Isenberg (

2010) Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Model to Iran, emphasizing the roles of government intervention, financial support, technological infrastructure, cultural context, and the stages of startup development. The findings highlight the need for a cohesive policy framework that sustains both early formation and long-term scaling, fostering a more resilient and dynamic entrepreneurial landscape.

Guided by these aims, the following research questions are addressed: What are the major challenges facing entrepreneurial ecosystems in developing countries? How can big data and natural language processing enhance our understanding of these challenges? How can news media be leveraged as a proxy for ecosystem monitoring in contexts where reliable data are scarce?

Ultimately, this research underscores the importance of developing innovative methodologies to study entrepreneurial ecosystems in data-scarce environments. By leveraging big data analytics and news as a proxy for ecosystem dynamics, it contributes to more informed policy design in contexts where institutional weaknesses and resource constraints hinder traditional data collection. Beyond Iran, these insights advance global debates on entrepreneurship and innovation in developing economies, where resilient and inclusive ecosystems are critical for sustainable growth. Beyond Iran as a case study, these insights advance global debates on entrepreneurship and innovation in developing economies, where resilient and inclusive ecosystems are critical for sustainable growth.

The paper proceeds as follows:

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on entrepreneurship policy challenges and text-based approaches;

Section 3 describes the methodology;

Section 4 presents findings and analysis;

Section 5 offers further discussion with implications for policy and research;

Section 6 concludes; and

Section 7 offers limitations of the study and future research.

2. Review of Related Literature

2.1. Entrepreneurship Policy Challenges in Developing Countries

Entrepreneurship policy challenges in developing countries are multifaceted and require tailored approaches. Collaborative entrepreneurship, including cultural collaboration and community innovations, is crucial for addressing these challenges (

Ratten, 2014). However, the connection between entrepreneurship policy and activity is weaker in developing countries compared to developed nations. This often results from the implementation of poorly aligned policies, resource constraints, and inconsistent execution (

Schøtt & Jensen, 2008). These findings highlight the importance of designing and implementing context-specific policies to promote entrepreneurship and economic development.

Public policies and macro-environmental factors that are unfavorable to entrepreneurship significantly contribute to business failure within the policy domain.

Minniti (

2008) demonstrated that startups often face severe obstacles when legal, regulatory, financial, and political frameworks fail to support their operations. Similarly,

Cantamessa et al. (

2018) highlighted that an adverse governmental environment not only affects startups directly but also discourages potential customers from engaging with these ventures while increasing operational costs. External factors such as economic instability, regulatory changes, and unforeseen events—including natural disasters and global crises—further undermine startup sustainability. Such external shocks disrupt market dynamics and challenge even well-prepared businesses.

Nair and Blomquist (

2019) explained that the influence of the environment on startup failure is highly contextual, varying significantly depending on the venture’s location. This complexity underscores the necessity for policymakers to create resilient entrepreneurial ecosystems that can withstand external disruptions. This aligns with findings from frontier markets where capability-building under uncertainty enabled firms to internationalize despite weak institutions (

Jahanbakht et al., 2022).

Beyond firm-level hurdles, developing-country ecosystems face additional structural policy challenges. Persistent credit gaps and collateral requirements constrain early-stage finance, disproportionately affecting new and women-led ventures unless legal frameworks enable lending against movable assets and targeted instruments such as guarantees are deployed (

Beck & Demirguc-Kunt, 2006;

World Bank, 2014). Digital entrepreneurship also requires complementary policies—support for capability-building, infrastructure, and market access—without which innovative ventures in emerging economies struggle to scale (

Acs et al., 2017). Meta-reviews of entrepreneurship programs across developing countries underscore that training and credit schemes alone produce uneven results unless embedded in broader ecosystem reforms (

McKenzie, 2017). Talent dynamics add further complexity: high-skill migration drains local entrepreneurial capacity unless governments cultivate “brain circulation” through diaspora linkages (

Wescott & Brinkerhoff, 2006). Finally, macro-fiscal constraints—particularly rising debt-service burdens—limit governments’ ability to sustain ecosystem investments, reinforcing the need for high-leverage, system-wide interventions (

World Bank, 2023). An additional but often overlooked policy challenge concerns the governance of data itself. In many developing countries, scarce and fragmented datasets become targets for extraction by foreign firms, resulting in informational resources being captured externally rather than reinvested locally. This has been characterized as a form of algorithmic or digital coloniality, whereby data gathered in the Global South fuels technological development elsewhere with minimal spillover benefits to domestic ecosystems (

Travers, 2024;

Heeks et al., 2024). Addressing this challenge requires policies that protect data sovereignty and ensure that digital resources contribute to local entrepreneurial capacity.

Taken together, these challenges highlight the need for systematic frameworks that capture the multi-dimensional character of entrepreneurial ecosystems.

2.2. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Frameworks

Entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs) are complex networks of interdependent actors and elements that promote high-growth ventures while reducing startup risks. As research in this field evolves, examining both internal dynamics and external influences becomes critical for policy design. Recent studies on IoT startups in emerging economies further emphasize the importance of tailored strategies for technology acquisition and capability development (

Tondro et al., 2025).

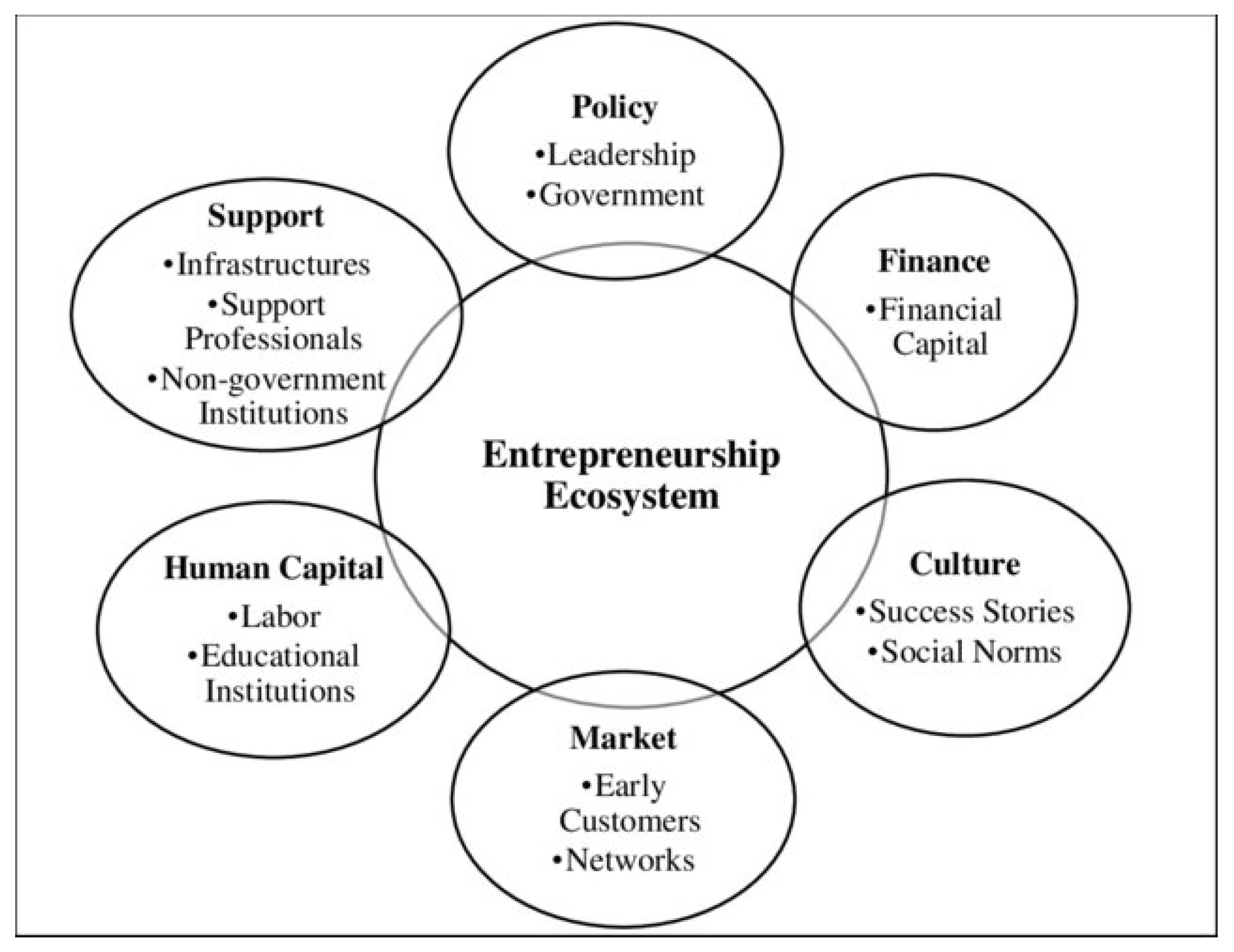

Isenberg (

2010) Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Model provides a widely recognized framework for identifying the core components of a vibrant startup ecosystem. The model organizes 12 interrelated elements into six domains—policy, finance, culture, support systems, human capital, and markets—each of which contributes to entrepreneurial activity in distinct yet interconnected ways (see

Figure 1). This framework has been widely adopted by policymakers, researchers, and practitioners as a tool for diagnosing ecosystem deficiencies and identifying opportunities for targeted interventions.

Policymakers can use this model to identify weaknesses in their local ecosystems. For example, limited access to finance can prompt targeted initiatives to attract investors. The model underscores the interdependence of the six domains, emphasizing collaboration among stakeholders—governments, educational institutions, private sector entities, and entrepreneurs—to establish a cohesive support system. Isenberg’s framework also allows for the customization of interventions based on the unique characteristics of each entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Yet while these frameworks provide valuable conceptual clarity, their practical application is often hampered by limited and unreliable data in developing countries.

2.3. Data Scarcity and News as Proxy for Policy Analysis

Understanding the dynamics of startup ecosystems in developing countries is particularly important due to their potential to drive economic growth, job creation, and innovation. However, these ecosystems often face significant challenges, including limited resources, inadequate infrastructure, and restrictive regulatory environments. Despite growing entrepreneurial activity, many developing countries struggle to translate this dynamism into substantial economic growth due to persistent structural obstacles.

Limited access to reliable data further complicates efforts to effectively analyze and compare entrepreneurial activities across regions (

Audretsch et al., 2022). In the absence of robust datasets, news media serves as a valuable proxy for understanding the dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems and associated policy challenges. News coverage acts as a real-time indicator of ecosystem conditions, enabling researchers and policymakers to derive insights into pressing issues. The integration of Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques enhances the capacity to analyze large volumes of news data efficiently. For instance,

Bejjani (

2023) discusses how digital media influences the development of entrepreneurial ecosystems, highlighting the role of media in shaping public perception and policy decisions.

Ecosystems are characterized by the complex interplay of biophysical, social, and economic factors. Comprehensive data is often necessary to understand these dynamics. However, in data-scarce environments, news coverage can offer valuable insights into emerging challenges and stakeholder concerns. As a reflection of real-time developments, news serves as a critical resource for identifying policy issues requiring immediate intervention.

Leveraging news as a proxy enables policymakers to remain informed about public discourse and emerging ecosystem challenges. This responsiveness facilitates the development of adaptive policy frameworks that address contemporary issues. Furthermore, understanding how news coverage shapes public perceptions can influence the design and acceptance of policies aimed at resolving ecosystem challenges.

Recognizing the value of news as a proxy encourages its integration into broader data collection strategies. By combining qualitative insights from news with quantitative data from traditional sources, policymakers can adopt a hybrid approach that enriches assessments of ecosystem health. The systematic analysis of news content provides a complementary perspective to conventional methods, offering a more nuanced understanding of entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of news as a proxy for capturing social positions on various topics, including environmental concerns (

Balahur et al., 2013). In developing countries where conventional data is often scarce or unavailable, utilizing news media offers an alternative pathway for gathering insights into ecosystem challenges. This highlights the importance of innovative methodologies in entrepreneurship research. For instance, big data analytics can identify ecosystem gaps and inform targeted interventions to enhance entrepreneurial outcomes (

Guerrero et al., 2021).

Recent studies have also shown a growing interest in utilizing news as non-traditional sources of unstructured data to measure policy-related uncertainty. The Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) index, developed by

Baker et al. (

2016), exemplifies this approach by quantifying newspaper dynamics through article counts across topics over time.

Azqueta-Gavaldón (

2017) enhanced the EPU index by automating topic extraction, applying it to the U.S. economy using data from three major newspapers. Subsequent research extended the index to multiple countries.

Baker et al. (

2020) further applied the EPU framework to gauge uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic, while

Nyman et al. (

2022) expanded the keyword lexicon with nearest-neighbor embeddings, showing causal relationships between their expanded set and the original EPU index. These contributions reinforce the credibility of news as a systematic and timely source for measuring uncertainty in economic and policy contexts.

These methodological advances create a natural bridge to the broader application of text mining and topic modeling in policy research.

2.4. Text Mining and Topic Modeling in Policy Research

Entrepreneurship policies in developing countries face additional challenges due to data scarcity, which impedes evidence-based policymaking. The absence of reliable data deprives policymakers of the foundation necessary to design effective programs (

Kantis et al., 2020). To address this issue, text mining and topic modeling techniques are increasingly used in policymaking. These methods analyze large volumes of textual data to provide insights into policy content and discourse (

Lesnikowski et al., 2019). For example, topic modeling has been applied to analyze adaptation policy documents, political statements, and municipal debates on climate change (

Lesnikowski et al., 2019). Text mining also helps overcome policymakers’ bounded rationality, supporting decision-making in complex environments (

Ngai & Lee, 2016). Structural topic modeling has been used to track how research on policy implementation has evolved over time (

Wu & Zhang, 2022), while

Azad et al. (

2024) applied similar methods to identify themes and opportunities in pro-environmental policymaking. Comparable approaches have also been employed to assess how ICT institutions and digital infrastructures shape entrepreneurial ecosystems in developing contexts, using both qualitative evidence and satellite data proxies (

Tondro et al., 2022).

Recent advancements highlight the versatility of these methods across diverse policy domains. In policy discourse analysis,

Nowlin (

2016) used latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) to extract issue frames from U.S. Congressional hearings, while

Lindahl and Börjeson (

2018) employed topic modeling to explore shifts in Swedish housing policy discourse.

Gilbert et al. (

2018) combined computational simulations with topic modeling to replicate public policy processes, demonstrating how machine learning can enhance scenario testing.

Other studies apply these tools in crisis and security contexts.

Altaweel et al. (

2019) examined ecological policy documents and revealed a shift from historical resource management issues to contemporary challenges such as climate change and biodiversity.

Hajdinjak et al. (

2020) used structural topic modeling to analyze migration policy debates in the United States and Canada, uncovering tensions between humanitarian and security narratives. Similarly,

Eckhard et al. (

2023) analyzed United Nations Security Council debates on Afghanistan, using NLP to trace shifts in rhetorical strategies and institutional positioning.

Applications extend to economic and institutional policymaking as well.

Warin and Stojkov (

2023) studied European Central Bank speeches, identifying dominant themes during crisis periods and linking them to central bank independence.

Kaminski et al. (

2023) proposed integrating AI simulations with topic models to support transparent computational policymaking.

Samuel et al. (

2023) emphasized the need for methodological standards in evaluating text-based policy models, while

Meier and Eskjær (

2024) used topic modeling to analyze three decades of Danish climate news, showing how citizens’ reliance on public-service media shaped the framing of environmental policies.

Finally, social and educational policies have become a growing domain for text-based analysis.

Maiya and Aithal (

2023) examined changes in U.S. university admission policies under different administrations,

Lee et al. (

2023) developed a framework for economi policy uncertainty in China, and

Jo and Sim (

2022) analyzed English-language education reforms, illustrating how policy changes influence both classroom practice and academic research.

Taken together, this body of work demonstrates that text mining and topic modeling are powerful tools for analyzing large-scale, unstructured policy data. By enabling researchers to detect discursive patterns, trace the evolution of policy priorities, and simulate decision-making, these methods expand the capacity of policymakers to design evidence-based interventions, particularly in contexts where conventional data are limited.

Topic modeling has emerged as a particularly valuable analytical tool in areas lacking comprehensive data, such as those in local and developing government contexts.

Grassia et al. (

2024) conducted a bibliometric analysis of regional competitiveness literature, emphasizing its role in shaping sub-national economic and social strategies.

Choi et al. (

2023) showed how topic modeling helps identify and prioritize policy themes, such as strengthening official development assistance at the local level in Korea.

Aytaç and Khayet (

2023) applied BERTopic in membrane distillation policy research, illustrating how advanced NLP techniques can guide both global and local policy agendas. These examples highlight the adaptability of topic modeling to diverse contexts, including those with limited data availability—conditions directly comparable to entrepreneurial ecosystems in developing countries.

2.5. Entrepreneurship Research and Topic Modeling

Beyond the policy domain, text mining and topic modeling have gained traction in entrepreneurship research, where they are used to map research trends, uncover cross-disciplinary connections, and assess how external factors shape entrepreneurial ecosystems.

A major stream of work explores the intersection of information technology and entrepreneurship.

Harb and Shang (

2022) applied topic modeling to entrepreneurship literature and identified six key dimensions, including innovation, strategy, and business models, highlighting the extent to which digital transformation is reshaping entrepreneurial activity.

Another area focuses on entrepreneurial universities and academic entrepreneurship.

Arroyabe et al. (

2022) mapped twenty years of scholarship and identified twenty distinct themes centered on knowledge commercialization, university–industry linkages, and the cultivation of entrepreneurial talent. Their study underscores how higher education institutions serve as critical actors in fostering innovation ecosystems.

Topic modeling has also provided insights into the long-term evolution of entrepreneurship research.

Wang et al. (

2023) analyzed the literature from 2000 to 2020, showing a marked shift of entrepreneurship studies into top-tier management journals, signaling greater theoretical and practical recognition of the field.

Singh (

2023) extended this work by identifying eight thematic clusters, ranging from the role of government policy to the influence of entrepreneurial ecosystems on innovation and competitiveness.

Collectively, these studies demonstrate that computational text analysis provides more than a descriptive overview of the entrepreneurship literature. It reveals how research agendas evolve, how ecosystems respond to technological and institutional change, and how entrepreneurship as a field is increasingly integrated with economics, sociology, and information systems. Importantly, the use of these methods in entrepreneurship remains concentrated in developed contexts, leaving significant scope for their application in emerging economies, where entrepreneurial ecosystems face unique institutional and data constraints.

Despite these contributions, most applications remain concentrated in developed-country settings, leaving significant gaps for entrepreneurship and policy research in emerging economies.

2.6. Literature Gaps

One major gap in the existing literature is its predominant focus on developed countries, which largely overlooks significant policy challenges in entrepreneurial ecosystems in emerging economies. Furthermore, prior research has primarily focused on English-language analysis, with limited attention to natural language processing (NLP) in Persian (Farsi). This presents both a technical challenge and an opportunity to advance NLP for non-English languages. Finally, the literature on policymaking to promote entrepreneurship has largely neglected the potential of big-data-driven approaches.

3. Methodology

This research utilized Natural Language Processing (NLP) to extract relevant information from news articles, enabling the construction of a semantic framework based on the content. NLP employs computational techniques to automatically analyze text and extract meaningful information, which can then be used for further analysis.

In policy analysis, the vast volume of textual data—ranging from parliamentary debates to news articles—poses significant challenges for manual processing. NLP has emerged as a cost-effective solution for automating the analysis of such extensive datasets. Its growing importance in policymaking is evident through successful applications in tasks such as classification, information extraction, summarization, and translation. As a result, NLP is increasingly being integrated into policy decisions and public administration practices.

This study combined topic modeling and text analysis techniques to identify and analyze underlying themes and patterns in the corpus. Before applying topic modeling, the text data underwent preprocessing to remove stop words, punctuation, and special characters. For Persian text, preprocessing involved several language-specific steps: normalization of “yeh/kehe” variants, removal of diacritics, half-space handling, and tokenization. Stemming and lemmatization were applied using the Hazm library (v0.7.0), with supplementary checks from Parsivar to validate outputs. Stop-words were removed based on Hazm’s default list, with minor manual additions to account for common Persian function words. The stop-word list is included in the replication package (or available upon request). These steps ensured that Persian-specific linguistic features were systematically handled prior to topic modeling.

Following preprocessing, the data was transformed into a bag-of-words representation, where each document was expressed as a vector of word frequencies. To adjust for word frequency bias, the Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF–IDF) weighting scheme was applied, which down-weights extremely common terms while preserving discriminative vocabulary. This representation was then used as input for topic modeling.

Although Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) is most often estimated on raw count vectors, recent applied studies have shown that TF–IDF pre-weighting can improve interpretability by reducing noise from highly frequent but semantically uninformative words. In this study, the TF–IDF representation was used to enhance topic distinctiveness before fitting the LDA model. We recognize that this design choice may influence word–topic distributions, and therefore note in the limitations that future research should complement LDA with alternative approaches such as Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) or embedding-based models (e.g., BERTopic) to assess the robustness of extracted themes.

To ensure robustness and reproducibility, model selection followed a systematic search procedure. We estimated models across a range of topic numbers (K = 5–25) and evaluated them using the c_v coherence metric. The final model was selected based on the highest coherence score while ensuring interpretability of the topics. Hyperparameters were set to symmetric priors (α = η = 0.01). Training used 500 iterations and 20 passes to ensure convergence. To assess stability, the model was run under multiple random seeds, and topic overlap across runs exceeded 85%, confirming replicability of the extracted themes. A small held-out subset of documents was used to validate coherence trends. These specifications are included in the replication package for transparency.

The preprocessed text data was then input into a Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model, a widely used topic modeling algorithm. LDA operates on the assumption that each document represents a mixture of topics and that each topic comprises a mixture of words. The resulting topic model was interpreted by analyzing the top words associated with each topic. Coherence scores were used to evaluate the topics, providing insights into their semantic meaning and relevance. Based on their content, the topics were labeled and categorized, which facilitated the identification of underlying themes and patterns within the corpus. The methodology is depicted in

Figure 2.

The topic modeling was performed using the Gensim library (v4.3.1) in Python (v3.10), which offers an efficient and scalable implementation of the LDA algorithm. The TF-IDF weighting scheme was implemented using the scikit-learn library (v1.3.2).

We collected longitudinal data from reputable news sources spanning 2017 to 2022. Web scraping techniques were employed to extract information from online news agencies. Web scraping, also known as web crawling, facilitates the automated collection and storage of data from the internet. Tools such as Beautiful Soup (v4.12.2) and Selenium (v4.10.0) in Python were utilized due to their efficiency in handling both dynamic and static web pages.

To respect ethical standards, scraping was limited to publicly available articles, and site-level restrictions (robots.txt) were checked prior to collection. Only full-text news articles (titles and body text) were retained, while advertisements, comment sections, and duplicate syndications were excluded. Duplicate articles across outlets were identified by URL and publication date and removed to avoid overrepresentation.

To ensure the reliability and accuracy of the information, data was sourced from established and credible news platforms as noted in

Table 1. The table below lists the news sources from which information, including the text and body of news links, was extracted.

Data were retrieved between June and August 2023, and retrieval dates per outlet were logged to ensure reproducibility. This approach aligns with best practices in transparent data collection while minimizing compliance risks. While the original scraper code is not publicly shared, we provide detailed documentation of all preprocessing steps (including Persian-specific normalization and stop-word resources), model configurations (priors, seeds, and number of topics), and topic modeling outputs. These materials will be made available upon request to researchers, ensuring transparency and reproducibility.

It should be noted that reliance on domestic news outlets introduces potential limitations, including selective reporting and informational bias. These issues, along with broader data voids in developing-country contexts, are discussed further in the

Section 7.

4. Results

4.1. Media Coverage, ICT Expansion, and Ecosystem Growth

News coverage of the entrepreneurial ecosystem grew significantly throughout the study period.

Figure 3 depicts the annual number of digital news articles on startups included in the dataset.

From 2016 to 2017, article counts rose from just 33 to 544, marking the first substantial jump in ecosystem visibility and providing the rationale for selecting 2017 as the starting point of this study. Between 2017 and 2018, media coverage of Iran’s startup ecosystem rose sharply again, with article counts increasing from 544 to over 2000. Coverage then remained relatively stable through 2022, reflecting a sustained elevation in policy and public attention. This rise reflects growing interest and investment in the sector, highlighting the vital role of startups in driving economic growth and innovation. While rising media coverage reflects growing social and policy attention to startups, parallel developments in ICT infrastructure provided the practical foundation for entrepreneurial activity.

Access to information and communication technologies (ICTs) facilitates the creation and growth of new enterprises (

Del Giudice & Straub, 2011). ICTs enhance entrepreneurs’ ability to collect, process, and interpret information while fostering an environment conducive to innovation and new business opportunities, particularly in online markets. Key indicators of ICT access include mobile-cellular telephone subscriptions, internet usage, and fixed-broadband subscriptions (

Gomes & Lopes, 2022).

Figure 4 illustrates the growth of internet usage and the number of individual internet users in Iran, demonstrating the increasing accessibility of ICTs.

Internet access is essential for mobile technology and significantly impacts the information society by improving information dissemination and supporting entrepreneurship. The widespread adoption of mobile phones and broadband internet has enhanced the business environment, reduced startup costs, and facilitated networking among entrepreneurs, customers, suppliers, and competitors. Consequently, reliable internet services are crucial for fostering innovation and growth in the entrepreneurial landscape. This resonates with earlier findings that IoT and AI-based startups in developing countries adopt disruptive technologies to overcome structural barriers and generate new growth opportunities (

Tondro & Jahanbakht, 2023).

Parallel to rising media coverage, ICT infrastructure expanded substantially during this period.

Figure 4 shows the growth of internet penetration in Iran, which provided enabling conditions for entrepreneurial activity. While our data do not allow us to identify causal effects, the co-movement between ICT indicators and startup-related news coverage suggests that digital connectivity created a supportive environment for startups to emerge and expand. In this sense, ICT development is best understood as a correlated background factor that shaped the opportunities available to entrepreneurs, rather than a direct causal driver of ecosystem growth.

Table 2 below presents the extracted topics in descending order based on their proportion within the dataset, providing an overview of the main themes discussed in startup-related news between 2017 and 2022.

The evolution of themes over time illustrates how Iran’s ecosystem adapted to shifting opportunities and constraints. In 2017, Iran’s startup ecosystem began to expand, driven by government initiatives and the establishment of supportive infrastructure. Despite the challenges faced by startups, particularly in the online ride-hailing sector, advancements in technology and evolving Internet regulations shaped the ecosystem. These developments created both obstacles and opportunities for innovation.

In 2018, Iranian policymakers prioritized the promotion of a knowledge-based economy. This initiative spurred the emergence of domestic social network startups and led to significant advancements in the ecosystem. The growth of Insurtech and increased investments in ride-hailing services signaled a transition toward a more competitive and mature entrepreneurial environment.

By 2019, the ecosystem shifted its focus to enhancing investment and financing mechanisms to facilitate market entry for startups. However, these efforts occurred amid restrictive internet policies that continued to challenge ecosystem development. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic prompted the government to implement proactive policies, including substantial investments and grants for technology-based startups. These measures helped sustain the ecosystem during a period of economic uncertainty. The surge in online activities during the pandemic underscored the importance of high-quality internet services. This demand contributed to the significant growth of video-based startups and drove policymakers to expand stock market opportunities to support emerging companies.

In 2021, the ecosystem faced further challenges due to proposed internet restrictions. Despite these obstacles, the surge in digital currency prices spurred government efforts to regulate emerging businesses. Additionally, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic reshaped the entrepreneurial landscape, fostering innovation in online retail and pharmaceuticals to meet evolving consumer needs.

In 2022, political unrest and restricted internet access hindered entrepreneurial activities in Iran. Nevertheless, the emergence of tourism and health-related startups demonstrated the adaptability of entrepreneurs, particularly in response to the ongoing impacts of the pandemic.

Taken together, the analysis of topics over time shows that Iran’s entrepreneurial ecosystem progressed through multiple phases of development. These descriptive trends highlight the interplay between government policies, internet access, and sector-specific shifts. To deepen this analysis, the extracted topics were subsequently mapped onto

Isenberg’s (

2010) ecosystem framework, which organizes entrepreneurial activity into six interdependent domains.

4.2. Mapping Topics to Isenberg’s Ecosystem Framework

Following this descriptive analysis of annual dynamics, the extracted topics were systematically categorized using

Isenberg (

2010) entrepreneurship ecosystem model. ChatGPT was employed to assign topics to Isenberg’s domains, associating each with relevant indicators. This categorization facilitated a structured evaluation of Iran’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, which is particularly well suited to emerging economies.

To categorize the extracted topics under

Isenberg (

2010) six ecosystem domains, we used a semi-automated coding process. First, the topics were presented to ChatGPT (OpenAI GPT-4, temperature = 0, top-p = 1, April 2024 version) with prompts that explicitly requested domain assignment based on topic keywords. This process was run three times to ensure consistency. Subsequently, two human coders independently reviewed the assignments. Agreement between the coders was high (Cohen’s κ = 0.82), and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The final coded dataset and the exact prompt text are included in the replication package (available upon request). This approach ensured reproducibility and transparency while retaining substantive interpretability.

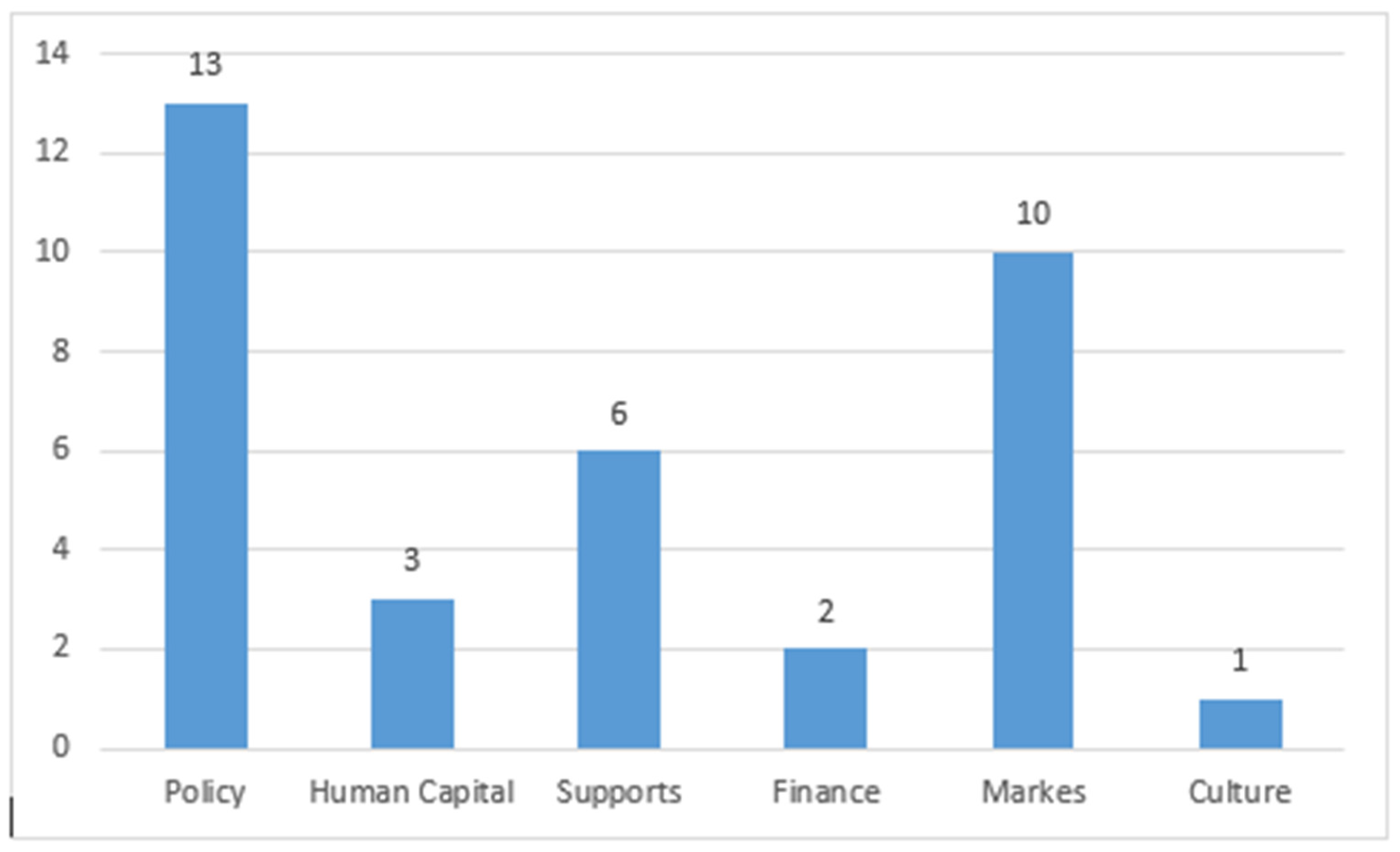

After mapping the topics, dynamic patterns across domains were analyzed (

Figure 5). The results highlight the dominance of policy interventions, the importance of supports (such as infrastructure and urban development), and the relatively underdeveloped state of finance. Notably, financing appeared with relatively low salience in the topic modeling results (

Table 3), suggesting that it was not a dominant theme in news coverage. However, this should not be interpreted as evidence that financing is unimportant. Rather, it highlights the limitations of relying on media sources: news salience does not necessarily reflect problem severity, and financing gaps remain a critical constraint for startups, as emphasized in prior research (

Beck & Demirguc-Kunt, 2006;

Kantis et al., 2020).

The government’s pivotal role in policy formulation—particularly licensing and internet regulation—emerges clearly. Its control over critical technological infrastructures underscores the centrality of policy interventions in shaping the startup landscape. These interventions have been instrumental in creating new markets and stimulating entrepreneurial activity.

4.3. Phased Evolution of the Iranian Ecosystem

Between 2017 and 2022, the Iranian startup ecosystem underwent significant transformation, progressing into its second phase of development. The findings show that Iran’s human capital index did not hinder access to skilled resources during this period, thanks to sustained investments in higher education, research, and entrepreneurship programs. At the same time, the support index proved critical, while financing mechanisms remained weak due to immature markets and structural constraints.

A closer look at the year-by-year narrative provides further detail on how the ecosystem evolved during this period:

2017: Expansion was driven by government initiatives and supportive infrastructure. Despite challenges in the online ride-hailing sector, advances in technology and internet regulation created both obstacles and opportunities.

2018: Policymakers prioritized the development of a knowledge-based economy. This initiative spurred the emergence of domestic social network startups and significant advancements across the ecosystem. Growth in Insurtech and ride-hailing services signaled a transition toward a more competitive and mature entrepreneurial environment.

2019: The ecosystem shifted its focus to enhancing financing mechanisms and investment support. However, restrictive internet policies continued to constrain development despite these financial initiatives.

2020: The COVID-19 pandemic prompted proactive government measures, including substantial investments and grants for technology-based startups. Online activity surged, fueling growth in video-based startups and expanding stock market opportunities for emerging firms.

2021: Proposed internet restrictions created new barriers. Simultaneously, the rise of cryptocurrency markets and the ongoing pandemic reshaped the entrepreneurial landscape, driving innovation in online retail and digital pharmaceuticals.

2022: Political unrest and restricted internet access hindered entrepreneurial activity. Nevertheless, tourism and health-related startups demonstrated resilience and adaptability in responding to pandemic aftershocks.

While this granular chronology highlights short-term developments, Iran’s entrepreneurial ecosystem has also unfolded along a broader three-phase trajectory

1:

Phase 1 (2000–2013): Foundations. This early period was characterized by a limited presence of startups but laid the groundwork for entrepreneurial growth. Advancements in technology and the introduction of startup-focused literature provided a necessary intellectual foundation. Initiatives such as

startup weekends and indirect government support played pivotal roles in fostering entrepreneurial activity. Evidence from Iran’s digital entrepreneurship sector shows that external enablers, such as technology intensity and policy interventions, were already shaping venture creation (

Jahanbakht & Ahmadi, 2025).

Phase 2 (2013–2019): Systematic Development. This period marked systematic ecosystem growth, supported by increased government involvement and the establishment of incubators and venture capital funds. Direct government policies aimed at nurturing startups became a defining feature, while collaboration between startups and established industries further stimulated innovation. The incorporation of entrepreneurship into university curricula, the rise of technology-focused startups, and diverse financing avenues and accelerators spurred a nationwide surge in startup activity. Industry–academia collaborations and entrepreneurship training programs reinforced this expansion, positioning Iran as a regional hub for innovation.

Phase 3 (Post-2019): Stagnation and Challenges. The subsequent period was marked by stagnation, driven by a scarcity of specialized talent, declining infrastructure quality, restrictive cyber laws, and economic recession. Despite ongoing government support, the ecosystem faced setbacks, including the migration of startup teams to more favorable environments abroad. These dynamics underscored the need for strategic interventions to restore growth. Studies on global value chains in frontier markets demonstrate that integration into wider ecosystems requires both institutional support and entrepreneurial experimentation (

Jahanbakht & Mostafa, 2022).

Figure 6 summarizes these three phases—early foundations, systematic development, and post-2019 stagnation—highlighting the oscillating trajectory of Iran’s startup ecosystem and its dependence on institutional capacity, regulatory conditions, and external shocks.

4.4. COVID-19 and Sectoral Shifts in the Ecosystem

The analysis of news data from Iran reveals distinct characteristics of the startup ecosystem in developing countries, which differ significantly from those in developed nations. Entrepreneurial ventures in developing countries exhibit notable differences compared to their counterparts in advanced economies (

Kumar & Singh, 2020). This suggests that the startup ecosystem in developing countries is shaped by a unique combination of environmental, economic, and cultural factors not typically found in other regions. These findings highlight the importance of developing a nuanced understanding of startup ecosystems in developing countries and considering the specific contextual factors influencing their growth and development.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a pivotal event that profoundly altered the paradigm and created novel conditions within the startup ecosystem, with developing countries experiencing unique challenges. This global health crisis triggered a cascade of economic and social changes that impacted startups worldwide. In the aftermath of the pandemic, several issues have become apparent, including reduced startup activity, startup closures, and the widespread adoption of remote working practices.

Table 4 below shows the results of the topic modeling in the years after COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed an accelerated expansion of the Internet’s role in economic and social activities across developing countries. As connectivity deepened, sectors with direct or indirect links to the digital economy demonstrated substantial potential for growth. A notable example is the rapid rise of home entertainment and video-on-demand (VoD) startups, which experienced considerable expansion as improved Internet accessibility and quality created new consumer markets. This underscores the strategic importance of Internet-related ecosystems in driving economic development within these regions.

A significant consequence of the pandemic has been its profound impact on consumer behavior, which reshaped demand patterns and fostered the emergence of new markets. In developing countries, this shift was particularly evident in the rise of medical startups and the proliferation of online shopping platforms. Pandemic-induced changes—such as increased reliance on digital services, heightened health awareness, and a preference for essential goods—opened opportunities for innovative startups to thrive despite broader economic uncertainty.

The emergence of new medical startups was driven by the heightened demand for healthcare solutions and digital health services, including online pharmaceutical delivery and telemedicine. Similarly, e-commerce activities surged as lockdowns and mobility restrictions accelerated the adoption of online shopping. These transformations highlight the ability of developing-country ecosystems to leverage technological advancements and adapt to evolving consumer needs, thereby fostering both economic growth and entrepreneurial innovation in crisis conditions.

4.5. Empirical Synthesis and Theoretical Implications for Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

Beyond these descriptive results, the findings contribute to a broader theoretical understanding of entrepreneurial ecosystems in developing-country contexts. Following

Whetten’s (

2009) call for generating

theories in and from context, the Iranian case highlights mechanisms that not only explain local dynamics but also extend to comparable fragile ecosystems. The phased evolution of Iran’s ecosystem, illustrated through

Figure 6 and the topic trends summarized in

Table 2, demonstrates that ecosystems in developing contexts do not follow linear growth paths. Instead, they oscillate between expansion and stagnation depending on institutional capacity, regulatory restrictions, and external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic (

Table 4). This nonlinearity broadens entrepreneurial ecosystem theory, which often assumes a steady progression from emergence to maturity, by emphasizing the cyclical and contingent nature of development in fragile environments.

At the same time, reliance on news data—documented in the rising coverage shown in

Figure 3 and reinforced by the categorization of themes in

Table 3—illustrates how ecosystems in autocratic or data-scarce contexts are filtered through state or institutional narratives. This reliance produces both “data voids” and optimism bias (

Boyd & Golebiewski, 2018), which constrain what policymakers and entrepreneurs perceive as opportunities and risks. The Iranian case therefore underscores the need to theorize how informational asymmetries affect ecosystem legitimacy, knowledge flows, and decision-making under uncertainty—dynamics often overlooked in conventional ecosystem models.

Finally, while Iran’s trajectory is uniquely shaped by sanctions, cyber laws, and political constraints, the underlying mechanisms—persistent data scarcity, the dual role of the state as both enabler and constraint, and the acceleration of digital sectors during COVID-19 (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5)—are transferable to other developing-country ecosystems. This aligns with

Whetten’s (

2009) argument that contextually grounded studies can generate insights with broader theoretical value. By showing how context-specific barriers and enablers interact, this study contributes

from context by highlighting conditions under which entrepreneurial ecosystems can thrive or falter in fragile institutional environments.

Building on these insights, future research could extend the analysis by conducting comparative studies of nonlinear ecosystem trajectories across the Global South, integrating alternative data sources such as social media, investment records, and venture databases to triangulate and offset media bias, and examining how data colonialism—where external actors extract and monetize local data (

Travers, 2024;

Heeks et al., 2024)—reshapes entrepreneurial capacity by externalizing value creation away from fragile ecosystems. Together, these directions point to the importance of expanding both theory and methodology to better capture the realities of entrepreneurship in developing contexts.

5. Discussion

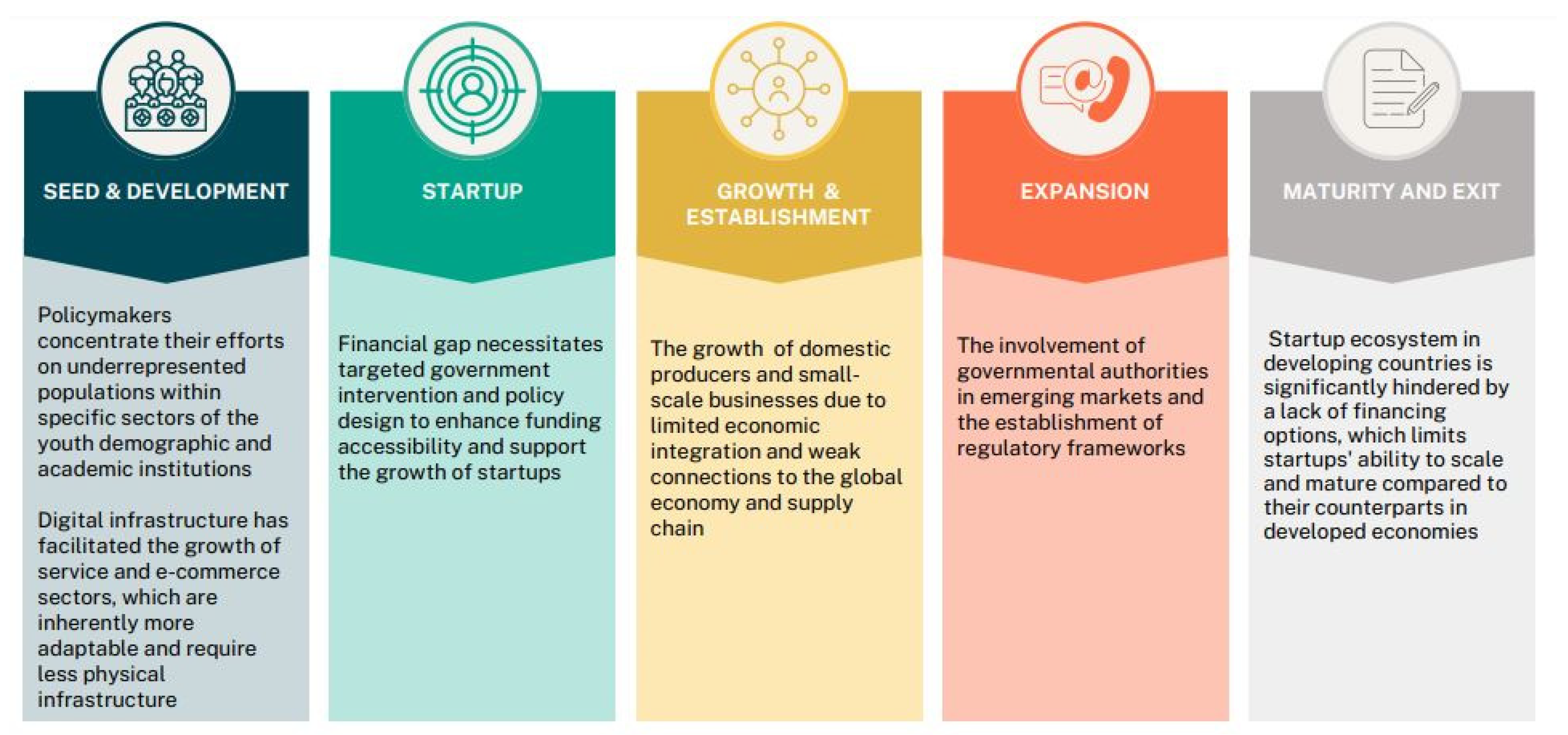

In developing countries, limited economic integration and weak connections to global value chains often result in fragmented markets (

World Bank, 2019).

Figure 7 illustrates the nonlinear stages of startup development in such contexts, showing how ecosystems often oscillate between early growth, stagnation, and selective maturity rather than progressing in a linear fashion. This fragmentation is reinforced by the dominance of local producers and small-scale businesses that typically lack the capital, resources, and networks needed to compete with large exporters and multinational corporations (

Ito et al., 2019).

Our results show that this challenge is particularly acute in Iran, where finance remained the weakest domain of the ecosystem (

Table 3). While ICT-driven services, e-commerce, and digital health startups flourished due to low entry barriers and scalability, ventures remained trapped in the early stages of their lifecycle. This aligns with the relatively low salience of finance in news coverage (

Table 3), a finding that reflects reporting priorities more than actual ecosystem needs. In practice, financing remains a structural bottleneck for scaling ventures, underscoring the importance of not conflating media visibility with policy relevance.

Figure 7 helps explain this dynamic: without adequate financing, ecosystems remain clustered around early-stage activity and cannot transition into sustained growth. Collateral-free loans, credit guarantees, and deeper venture capital markets are therefore critical if developing countries are to unlock broader economic impact.

At the same time, infrastructure and digital connectivity emerged as enabling domains that allowed Iranian startups to thrive in ICT services. Our topic modeling (

Table 2 and

Table 4) revealed how internet penetration, video-on-demand services, and online shopping surged during 2017–2022, particularly under the COVID-19 shock. This pattern, also visible in

Figure 7, reflects the centrality of digital platforms in fragile ecosystems: they require less physical infrastructure, scale quickly, and offer entrepreneurs with limited resources a viable entry point. However, the reliance on ICT sectors has also narrowed diversification, leaving industrial and manufacturing innovation underdeveloped.

The findings also highlight the double-edged role of policy. Government interventions in Iran—from licensing to incubator funding—were central to ecosystem expansion, yet restrictive cyber laws and regulatory volatility after 2019 contributed to stagnation. This reflects an asymmetry within Isenberg’s domains: policy and supports are overdeveloped, while finance and culture lag behind.

Figure 7 visualizes how such imbalances can push ecosystems into stalled phases, despite earlier signs of vibrancy.

Cultural dynamics further deepen this imbalance. Iran’s ecosystem was primarily driven by academic and youth-led startups, while older entrepreneurs, women outside universities, and rural founders remained marginalized. This exclusion limits inclusivity and resilience, producing a narrow entrepreneurial culture concentrated in specific demographics. The predominance of service-oriented and academic startups explains why broader industrial diversification did not occur, even when ecosystem activity peaked between 2013 and 2019.

Taken together, these findings highlight how nonlinear trajectories, informational asymmetries, and state-dominated ecosystems shape entrepreneurial development in fragile contexts. By explicitly linking empirical patterns to

Figure 7, our analysis demonstrates that ecosystems in developing countries do not progress linearly but cycle between growth and stagnation, depending on the balance of enabling domains. Iran’s experience underscores the importance of addressing financing gaps, strengthening digital infrastructure, and broadening participation across social groups to avoid systemic vulnerability.

Ultimately, the discussion positions Iran’s case within a broader theoretical perspective: ecosystems under fragility are characterized by oscillating stages, asymmetries across domains, and susceptibility to external shocks.

Figure 7 thus provides a conceptual tool for visualizing these dynamics, while the empirical results offer comparative insights that can guide both theory-building and policy design in other developing-country contexts.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the evolution of Iran’s startup ecosystem, showing its trajectory from early foundations through a period of structured growth to more recent stagnation. The Iranian case illustrates how government interventions—through regulation, education, and infrastructure—can simultaneously enable and constrain entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Beyond the Iranian context, three broader insights emerge. First, ecosystems in fragile environments rarely follow linear paths; instead, they cycle between expansion and contraction depending on institutional capacity, regulatory shocks, and crises such as COVID-19. Second, in data-scarce settings, big data and NLP techniques offer valuable tools for uncovering policy challenges and ecosystem dynamics in real time. Third, the Iranian experience highlights mechanisms—state dominance, informational bias, and digital acceleration—that resonate across many developing economies.

Taken together, these findings contribute both to contextual understanding of Iran and to the broader theorization of how entrepreneurial ecosystems evolve under conditions of fragility and constraint. While the specifics of sanctions and cyber regulations are unique, the underlying patterns have wider relevance for scholars and policymakers working in emerging markets.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This study has limitations that should be acknowledged. First, there is a data void: in many developing countries, comprehensive and reliable public data on startups, digital activity, or investment flows is scarce or unavailable. Government policies, reporting mechanisms, and institutional opacity can exacerbate these voids, restricting the availability of accurate datasets for research. As

Boyd and Golebiewski (

2018) highlight, such “data voids” can create conditions where critical gaps in reporting lead to distorted or incomplete pictures of reality. Consequently, some findings in this study may be based on incomplete information, limiting their generalizability.

Second, there is a potential bias in news data. This research relies on local and regional news sources to supplement missing datasets. While these outlets provide valuable coverage of entrepreneurial activity, they may also reflect selective reporting, editorial priorities, or state-affiliated agendas. In the Iranian context, this introduces the risk of informational gatekeeping and optimism bias, where successes aligned with official narratives are more visible than failures or risks. Methodologically, the use of bag-of-words and vocabulary pruning in topic modeling may further smooth away rare but policy-relevant terms. To address this risk, human-in-the-loop checks were used to validate topic coherence and ensure substantive interpretability, but residual bias cannot be eliminated.

Finally, although coherence metrics, multi-seed stability checks, and validation subsets confirmed the robustness of the chosen model, topic modeling remains sensitive to hyperparameter choices. Future research should test alternative priors, topic ranges, and modeling approaches to ensure that the identified themes persist across specifications.

Future studies may pursue triangulation with complementary data sources—including official statistics, international databases, and primary survey data—to enhance robustness and mitigate reliance on news-based proxies. Methodological extensions might also combine supervised machine learning with unsupervised topic models to capture both broad patterns and rare signals.