Corruption as a Key Driver of Informality: Cross-Country Evidence on Bribery and Institutional Weakness

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

1.2.1. Economic Development

- A.

- Developed Economies

- B.

- Developing Economies

- India

- West Africa

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Latin America and the Caribbean

- Russia and Eastern Europe

- Vietnam

- C.

- Emerging Economies

1.2.2. Thematic Sections

- A.

- Globalization

- B.

- Institutional Strength vs. Weakness

- C.

- Digital Technologies

2. Method

- 1.

- Corruption Dimension

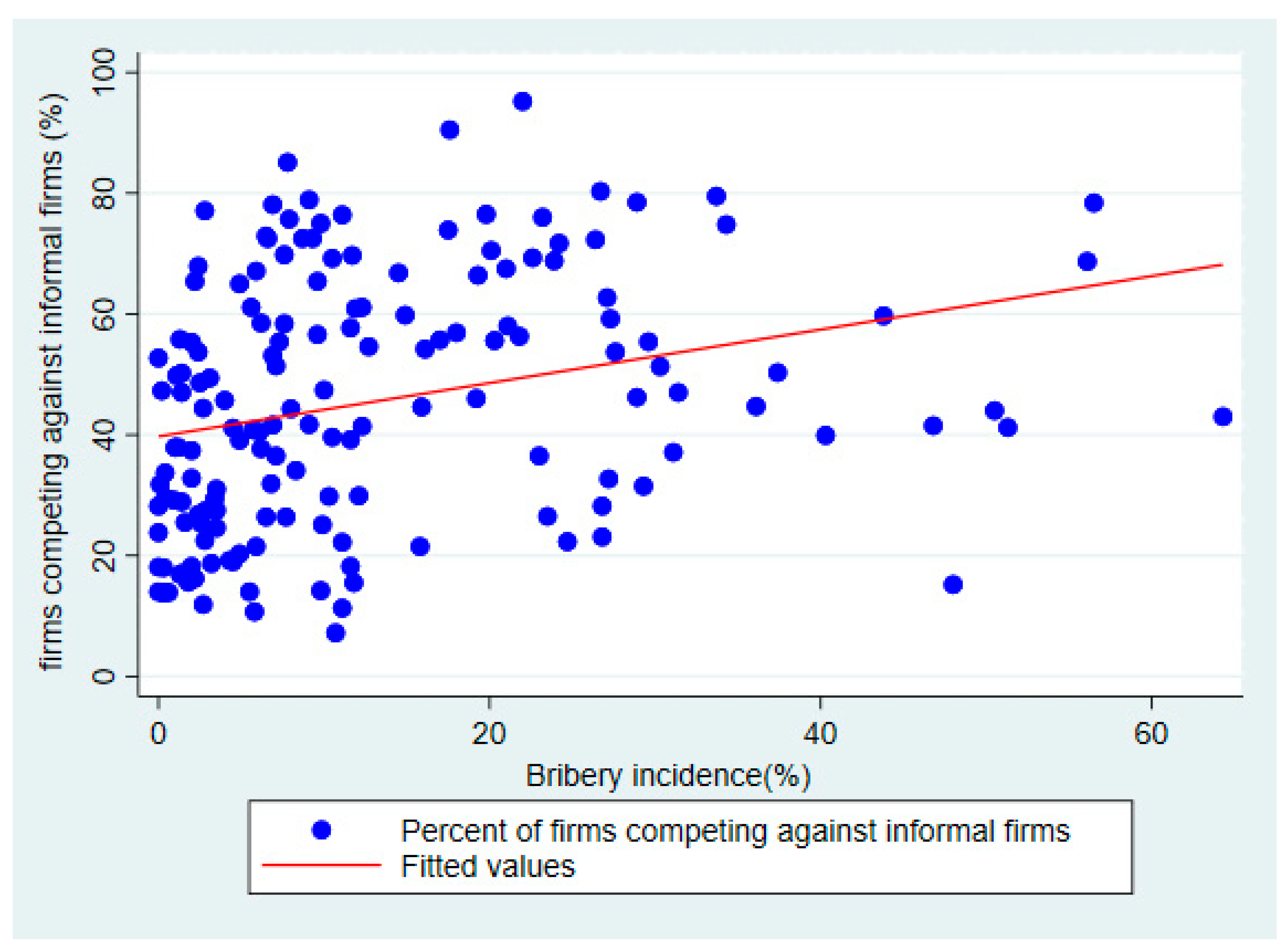

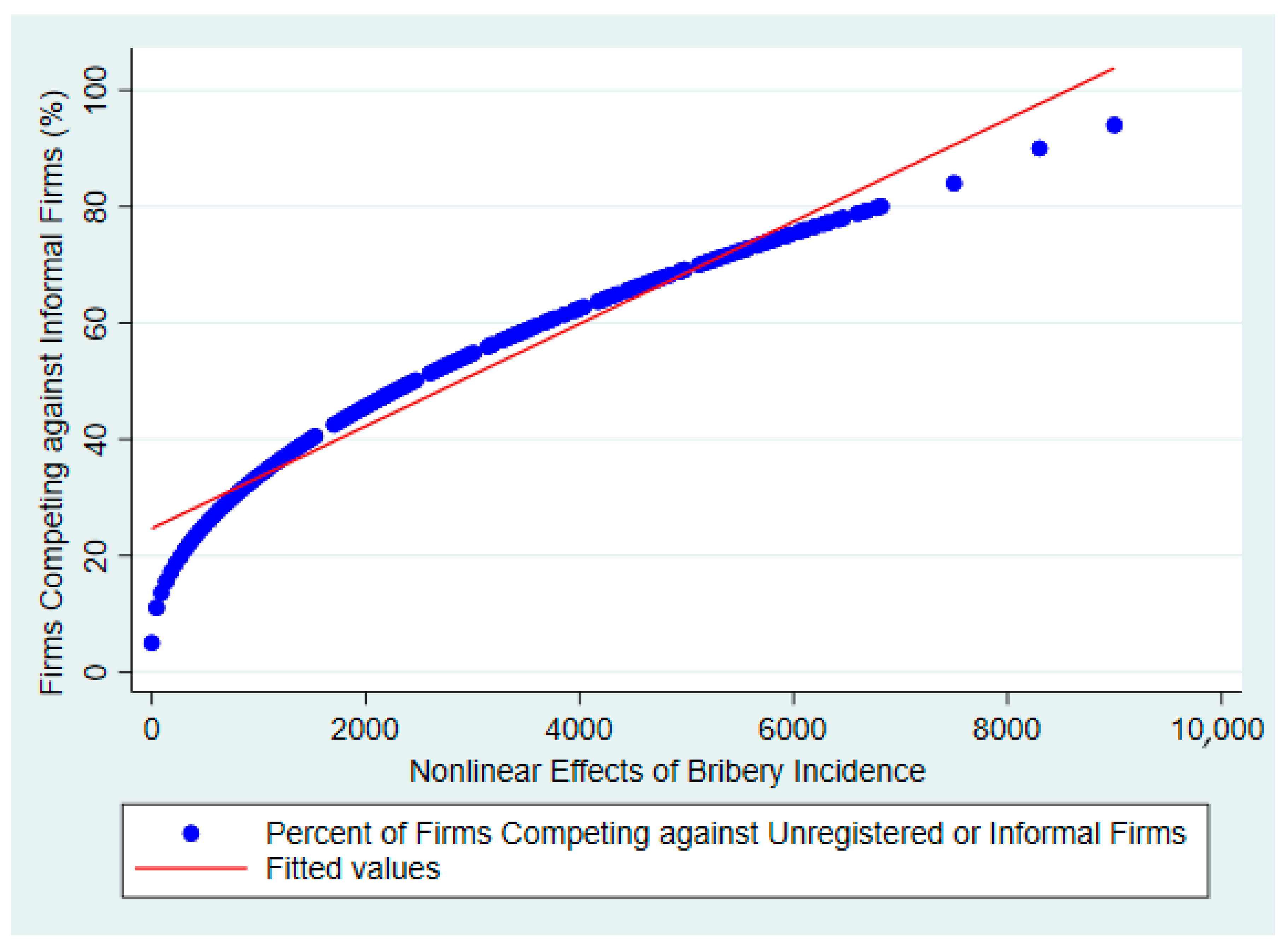

- Bribery incidence—the percentage of firms experiencing at least one request for an informal payment.

- Bribery depth—the share of public transactions where a bribe or gift was requested.

- 2.

- Regulatory Efficiency Dimension

- Days required to obtain an operating license (two separate indicators).

- Senior management time spent dealing with the requirements of government regulation (%).

- 3.

- Infrastructure Constraint Dimension

Endogenous Variables of Informality

- Percentage of firms competing against unregistered/informal firms.

- Percentage of firms formally registered at inception.

- Number of years firms operated without formal registration.

- Percentage of firms reporting informal competitors as a major constraint

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Informality

4.2. Rent-Seeking Behavior and Corrupt Practices

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajide, F. M., & Dada, J. T. (2023). Globalization and shadow economy: A panel analysis for Africa. Review of Economics and Political Science, 9(2), 166–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, M. R., Capasso, S., Ciucci, S., & Spagnolo, N. (2024). The non-linear effect of income on the shadow economy. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 95, 102041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluko, B., Garri, M., Owalla, B., Kim, J., & Pickernell, D. (2024). Informal institutions’ influence on FDI motivation and flow: A configurational fsQCA analysis of corruption as part of the MNEs’ FDI motivation system. International Business Review, 33(6), 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez-Camargo, C., Costa, J., Koechlin, L., Mukono, D., & Lugolobi, R. (2021). Informal networks as investment in East Africa. Basel Institute on Governance. Available online: https://edoc.unibas.ch/server/api/core/bitstreams/b70a7747-da56-4617-a644-fff7817a1ecf/content (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Barasa, L. (2025). Mobile money an antidote to petty corruption? A matched difference-in-differences analysis. Information Technology for Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, N., Beegle, K., Recanatini, F., & Santini, M. (2014). Informal economy and the world bank (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6888). World Bank. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2440936 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Bermúdez, P., Verástegui, L., Nolazco, J. L., & Urbina, D. A. (2024). Effects of corruption and informality on economic growth through productivity. Economies, 12(10), 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilan, I., & Apostoaie, C. (2025). Tax policy, corruption, and formal business entry: Cross-country evidence from emerging economies. Economic Change and Restructuring, 58(2), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodjongo, M. J. M., & Kamdem, W. B. (2024). Analysis of the gap in economic informality between Africa and the advanced and emerging countries. Journal of Economic Integration, 39(1), 198–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M. F., & Guccio, C. (2024). Exploring the corruption-inefficiency nexus using an endogenous stochastic frontier analysis. Southern Economic Journal, 91(3), 811–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caucheteux, J., Fankhauser, S., & Srivastav, S. (2025). Climate change mitigation policies for developing countries. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 19(1), 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes Gil, S. Y. (2025). Small stores, big obstacles: Understanding constraints and opportunities for micro-retail firms [Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology]. MIT DSpace. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/162313 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Chen, C., Pinar, M., & Stengos, T. (2024). Bribery, regulation and firm performance: Evidence from a threshold model. Empirical Economics, 66(1), 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M., Moelders, F., Salgado, E., & Volk, A. (2025). Estimating the number of firms in Africa. International Finance Corporation. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstreams/ad2895d4-8426-4d09-b092-5f82c82a8684/download (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Efthimiou, S. G. (2025). The economic adjustment and regional development of the tourism sector through foreign direct investments. Theoretical Economics Letters, 15(4), 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, R., & Lim, S. (2025). The influence of the informal economy on the growth rate of real GDP within the association of Southeast Asian nations. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 15(3), 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esaku, S. (2021). Does corruption contribute to the rise of the shadow economy? Empirical evidence from Uganda. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1), 1932246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, D. (2019). Informality, harassment, and corruption: Evidence from informal enterprise data from Harare, Zimbabwe. World Bank Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B. (2024). Corruption and informality in business in Serbia and Croatia [Doctoral dissertation, Universität Regensburg]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gindling, T. H., Mata, C., & Rojas, D. (2025). Job transitions and involuntary informality in Costa Rica (Working Paper 25-01). Department of Economics, University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Available online: https://economics.umbc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/243/2025/04/Gindling-Mata-Rojas_complete-manuscript-1.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., & Lagos Mondragon, R. (2025). Learning in the shadows: Informality and entrepreneurship in Brazil. York University & University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Available online: https://yanranecon.github.io/files/Informality_Draft_2.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Guritno, D. C., Kurniawan, M. L. A., Mangkunegara, I., & Wiraatmaja, D. (2025). Do public sector wages moderate the impact of institutional strengthening on corruption? Journal of Financial Crime. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwaindepi, A. (2024). Taxation in the context of high informality: Conceptual challenges and evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Review of Development Economics, 29(2), 1228–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyurko, F. A. (2021). Exploring the socio-legal aspects of low-level corruption: A study on the perceptions of informal practices of long-term local residents and migrants in Scotland and Hungary [Doctoral dissertation, University of Glasgow]. Available online: https://theses.gla.ac.uk/82625/ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Kelmanson, B., Kirabaeva, K., Medina, L., Mircheva, B., & Weiss, J. (2019). Explaining the shadow economy in Europe: Size, causes and policy options (IMF Working Paper No. 19/278). International Monetary Fund. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, A. O. (1974). The political economy of the rent-seeking society. The American Economic Review, 64(3), 291–303. [Google Scholar]

- Kubbe, I., Kırşanlı, F., & Nugroho, W. S. (2025). Corruption and informal practices in the Middle East and North Africa: A pooled cross-sectional analysis. Journal of Institutional Economics, 21, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lah, M. (2024). The economics of informality: The financing of the informal economy, criminal activities, and nonregulatory capital. Pré-publication, Document De Travail. Paris School of Economics & Paris Jourdan Sciences Économiques. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-04721877/ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- La Porta, R., & Shleifer, A. (2014). Informality and development. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavallée, E., & Roubaud, F. (2009). Corruption and the informal sector in Sub-Saharan Africa. Université Paris-Dauphine and DIAL. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/74748712/Corruption_and_the_informal_sector_in_Su20211116-15586-7tlxuk.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Lavallée, E., & Roubaud, F. (2018). Corruption in the informal sector: Evidence from West Africa. The Journal of Development Studies, 55(6), 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhartova, V. (2025). Corruption as an obstacle or an incentive to FDI flows: A panel data analysis. Montenegrin Journal of Economics, 21(3), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loayza, N. V. (1996). The economics of the informal sector: A simple model and some empirical evidence from Latin America. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 45, 129–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, M. R. V. (2023). Essays on the role of informality, corruption, and social networks in Brazil [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Brazil. Available online: https://repositorio.ufc.br/handle/riufc/75215 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Mara, E. R. (2025). Quo vadis shadow economy in a digitalized world? Evidence from panel cointegration for EU countries. Babeș-Bolyai University, Department of Finance, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/127291633/Quo_Vadis_Shadow_Economy_in_A_Digitalized_World_Evidence_from_Panel_Cointegration_for_EU_Countries_1 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Meagher, K. (2013). Unlocking the informal economy: A literature review on linkages between formal and informal economies in developing countries (IEG Working Paper 27). World Bank. Available online: https://www.wiego.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Meagher-Informal-Economy-Lit-Review-WIEGO-WP27.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Mishra, A., & Ray, R. (2013). Informality and corruption. Bath Papers in International Development and Wellbeing No. 21. Centre for Development Studies. Available online: https://researchportal.bath.ac.uk/en/publications/informality-and-corruption (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Nguimkeu, P., & Okou, C. (2019). Informality. In J. Choi, M. Dutz, & Z. Usman (Eds.), The future of work in Africa: Harnessing the potential of digital technologies for all (pp. 107–132). World Bank. Available online: https://books.google.cl/books?hl=es&lr=&id=k7z1DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT14&dq=The+future+of+work+in+Africa:+Harnessing+the+potential+of+digital+technologies+for+all+(pp.+107%E2%80%93132).+World+Bank.+&ots=6iaBUDD9DC&sig=arEiMX0PKqYgsnP8FEk3kSFXyX0 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Nguyen, T. M., Tran, Q. T., & Truong, T. T. T. (2024). Local corruption and corporate investment in an emerging market. Asia And The Global Economy, 4(2), 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noula, A. G., & Petnga, R. D. (2025). Interactions between the informal economy and income inequalities: The influence of political commitment in Africa. iBusiness, 17(1), 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwosu, J., & Folarin, O. (2025). Bridging the formality divide: A cross-national analysis of economic informality determinants. Journal Business and Economic Options, 8(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnsorge, F., & Yu, S. (2022). The long shadow of informality: Challenges and policies. World Bank Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (1999). Public sector corruption. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/public-sector-corruption_9789264173965-en.html (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2015). Consequences of corruption at the sector level and implications for economic growth and development. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017). Shining light on the shadow economy: Opportunities and threats. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2017/09/shining-light-on-the-shadow-economy-opportunities-and-threats_a9a92285/e0a5771f-en.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Orlova, A. V., & Boichev, V. (2017). “Corruption is us“: Tackling corruption by examining the interplay between formal rules and informal norms within the Russian construction industry. Journal of Developing Societies, 33(4), 401–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuma, G., Ayinde, A., Ntokozo, N., & Ehikioya, B. (2024). Evaluating the impact of systemic corruption and political risk on foreign direct investment inflows in Nigeria: An analysis of key determinants. Discover Sustainability, 5(1), 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. K. T. (2024). Impacts of national intellectual capital on informal economy: The moderating role of institutional quality. Competitiveness Review an International Business Journal Incorporating Journal of Global Competitiveness, 34(2), 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. (1993). The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. The American Prospect, 4(13). Available online: https://prospect.org/article/prosperous-community (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Quiros-Romero, G., Alexander, T., & Ribarsky, J. (2021). Measuring the informal economy. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravago, T., Tagal, M. G., Abante, M. V., & Vigonte, F. (2025, February 24). Corruption and trade efficiency in association of Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN): Sectoral impacts, policy insights, and the case of the Philippines. SSRN. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5151627 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Rdhaounia, N., & Elweriemmi, M. (2025). The effect of shadow economy on human capital in Tunisia: An ARDL bounds test approach. The Journal of Developing Areas, 59(2), 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-Ackerman, S. (1978). Corruption: A study in political economy. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Ackerman, S. (1999). Corruption and government: Causes, consequences, and reform. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F., Buehn, A., & Montenegro, C. E. (2010). Shadow economies all over the world: New estimates for 162 countries from 1999 to 2007 (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper). World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F., & Enste, D. H. (2000). Shadow economies: Size, causes, and consequences. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(1), 77–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafutdinova, G. (2018). Informality and corruption perceptions in Russia’s regions: Exploring the effects of gubernatorial turnover in patronal regimes. Russian Politics, 3(2), 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simatele, M., & Bolarinwa, S. T. (2024). How does globalization affect informality in sub-Saharan African countries? Sustainable Development, 33(1), 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, S. (2025). Uncovering the nexus of tax evasion and bribery in Latin America and the Caribbean. In Contemporary examination of Latin America and the Caribbean: Economy, education, and technology (pp. 171–198). IGI Global. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/uncovering-the-nexus-of-tax-evasion-and-bribery-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean/362725 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Smith, N., & Thomas, E. (2015). Determinants of Russia’s informal economy: The impact of corruption and multinational firms. Journal of East-West Business, 21(2), 102–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuong, N. T., & My-Linh, T. N. (2025). The impact of foreign direct investment and public governance on the shadow economy in emerging Asian countries. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 31(1), 300–318. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar Jalles, J., Pessino, C., & Calderón, A. C. (2025). Fiscal consolidations in Latin America and the Caribbean: Do inequality, informality and corruption matter? IDB. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullock, G. (1967). The welfare costs of tariffs, monopolies, and theft. Western Economic Journal, 5(3), 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, N. H., Nguyen, T. A., Hoang, T. B., & Cuong, N. V. (2024). Formal firms with bribery in a dynamic business environment. Journal of Business Ethics, 191, 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism: Firms, markets, relational contracting. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2025). World Bank Enterprise Surveys. Available online: https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/data (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Yao, J. (2024). Unveiling the Informal Economy: An Augmented Factor model approach. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinnbauer, D. (2020). Urbanisation, informality, and corruption: Designing policies for integrity in the city (A. Williams, Ed.). U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre. Available online: https://data.opendevelopmentmekong.net/dataset/a6bc5a82-e35a-469a-b8ea-7839a07c4a42/resource/268e4c1b-a407-473c-8a62-bbc65a12b8e2/download/u4_urbanisation-informality-and-corruption_designing-policies-for-integrity-in-the-city.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

| Indicator | All Countries | East Asia and Pacific | Europe and Central Asia | Latin America and Caribbean | Middle East and North Africa | South Asia | Sub-Saharan Africa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firms competing against unregistered or informal firms (%) | 44.1 | 36.5 | 28.8 | 60.4 | 44.4 | 34.5 | 60.6 |

| Average number of years firm operated without formal registration | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| Firms identifying informal competitor practices as a major or very severe constraint (%) | 23.8 | 10.7 | 16.9 | 32.6 | 32.2 | 17.3 | 33.7 |

| Indicator | All Countries | East Asia and Pacific | Europe and Central Asia | Latin America and Caribbean | Middle East and North Africa | South Asia | Sub-Saharan Africa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bribery incidence (firms experiencing at least one bribe payment request) (%) | 12.7 | 17.5 | 6.6 | 7.5 | 14.4 | 19.9 | 18.4 |

| Bribery depth (public transactions where a gift or informal payment was requested) (%) | 10.0 | 13.8 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 12.9 | 16.9 | 13.8 |

| Firms identifying corruption as a major or very severe constraint (%) | 26.2 | 14.5 | 15.6 | 40.1 | 41.1 | 23.4 | 35.2 |

| Variable | Informality 1 | Informality 2 | Informality 3 | Informality 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corruption 1 | 1.38 ** (0.63) | 0.61 * (0.34) | −0.03 (0.03) | 0.01 (0.40) |

| Corruption 2 | −1.35 * (0.73) | −1.05 (0.40) | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.17 (0.46) |

| Regulatory efficiency 1 | −0.20 (0.25) | 0.22 (0.13) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.16) |

| Regulatory efficiency 2 | −0.03 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.04 (0.03) |

| Infrastructural constraints | 0.56 *** (0.14) | −0.27 *** (0.07) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.68 *** (0.09) |

| _cons | 33.25 *** (3.61) | 91.57 *** (1.93) | 0.83 (0.18) | 10.27 *** (2.27) |

| Variable | Informality 1 | Informality 2 | Informality 3 | Informality 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corruption 1 | 30.64 | 31.04 | 31.04 | 30.64 |

| Corruption 2 | 30.06 | 30.47 | 30.47 | 30.06 |

| Regulatory efficiency 1 | 1.16 | 1.16 | 1.16 | 1.16 |

| Regulatory efficiency 2 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 1.14 |

| Infrastructure constraints | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 |

| Mean VIF | 12.82 | 12.99 | 12.99 | 12.82 |

| Variable | Informality 1 | Informality 2 | Informality 3 | Informality 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corruption 1 | 0.250 ** (0.125) | −0.277 *** (0.068) | −0.003 (0.006) | 0.151 * (0.078) |

| Regulatory efficiency 1 | −0.157 (0.249) | 0.256 * (0.135) | −0.014 (0.012) | 0.010 (0.155) |

| Regulatory efficiency 2 | −0.036 (0.047) | 0.022 (0.026) | 0.003 (0.002) | −0.036 (0.029) |

| Infrastructure constraints | 0.588 *** (0.139) | −0.251 *** (0.075) | 0.010 (0.007) | 0.672 *** (0.086) |

| _cons | 33.454 *** (3.638) | 91.729 *** (1.973) | 0.823 *** (0.182) | 10.248 *** (2.263) |

| Variable | Informality 1 (0.05 Quantile) | Informality 1 (0.1 Quantile) | Informality 1 (0.2 Quantile) | Informality 1 (0.75 Quantile) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corruption 1 | 0.472 *** (0.149) | 0.371 ** (0.163) | 0.267 * (0.160) | 0.357 * (0.210) |

| Regulatory efficiency 1 | −0.388 (0.297) | −0.465 (0.326) | −0.377 (0.318) | 0.218 (0.420) |

| Regulatory efficiency 2 | 0.032 (0.057) | 0.0001 (0.062) | −0.024 (0.061) | −0.011 (0.080) |

| Infrastructure constraints | −0.029 (0.166) | 0.167 (0.182) | 0.344 * (0.177) | 0.629 *** (0.234) |

| _cons | 14.123 *** (4.346) | 17.312 *** (4.767) | 20.185 *** (4.657) | 41.885 *** (6.138) |

| Variable | Informality 1 | Informality 2 | Informality 3 | Informality 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corruption 1 | 0.033 (0.030) | −0.249 *** (0.067) | −0.004 (0.006) | 0.066 (0.062) |

| Corruption 1 squared | 0.010 *** (0.000) | −0.001 *** (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.004 *** (0.000) |

| Regulatory efficiency 1 | −0.098 * (0.059) | 0.248 * (0.132) | −0.014 (0.012) | 0.033 (0.122) |

| Regulatory efficiency 2 | −0.003 (0.011) | 0.017 (0.025) | 0.003 (0.002) | −0.023 (0.023) |

| Infrastructure constraints | 0.008 (0.035) | 0.175 ** (0.078) | 0.007 (0.007) | 0.443 *** (0.072) |

| _cons | 20.460 *** (0.896) | 93.419 *** (2.012) | 0.745 *** (0.190) | 5.103 *** (1.864) |

| Variable | Informality 1 | Informality 2 | Informality 3 | Informality 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corruption 1 | 1.29 | 1.29 | 1.29 | 1.29 |

| Corruption 1 squared | 1.22 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 1.22 |

| Regulatory efficiency 1 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.21 |

| Regulatory efficiency 2 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 1.14 | 1.14 |

| Infrastructure constraints | 1.11 | 1.11 | 1.11 | 1.11 |

| Mean VIF | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.19 |

| Variable | Informality 1 (0.15 Quantile) | Informality 1 (0.25 Quantile) | Informality 1 (0.3 Quantile) | Informality 1 (0.32 Quantile) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corruption 1 | 0.107 * (0.056) | 0.104 * (0.055) | 0.103 ** (0.051) | 0.087 * (0.052) |

| Corruption 1 squared | 0.011 *** (0.000) | 0.010 *** (0.000) | 0.010 *** (0.000) | 0.010 *** (0.000) |

| Regulatory efficiency 1 | −0.184 * (0.110) | −0.240 ** (0.109) | −0.214 ** (0.101) | −0.217 ** (0.102) |

| Regulatory efficiency 2 | 0.002 (0.021) | −0.021 (0.021) | −0.016 (0.019) | −0.015 (0.019) |

| Infrastructure constraints | −0.083 (0.065) | −0.034 (0.064) | −0.054 (0.060) | −0.051 (0.060) |

| _cons | 15.527 *** (1.678) | 18.928 *** (1.661) | 19.351 *** (1.542) | 19.737 *** (1.556) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valdiglesias, J. Corruption as a Key Driver of Informality: Cross-Country Evidence on Bribery and Institutional Weakness. Economies 2025, 13, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100281

Valdiglesias J. Corruption as a Key Driver of Informality: Cross-Country Evidence on Bribery and Institutional Weakness. Economies. 2025; 13(10):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100281

Chicago/Turabian StyleValdiglesias, Jhon. 2025. "Corruption as a Key Driver of Informality: Cross-Country Evidence on Bribery and Institutional Weakness" Economies 13, no. 10: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100281

APA StyleValdiglesias, J. (2025). Corruption as a Key Driver of Informality: Cross-Country Evidence on Bribery and Institutional Weakness. Economies, 13(10), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100281