The Coordination of Monetary–Fiscal Policy in South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

Context of SA’s Macroeconomic Policy Coordination

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Literature Review

2.2. Empirical Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Institutional Independence—Policy Reaction Functions

3.2. A Set-Theoretic Approach

| TARGETS | Inflation Shocks (Monetary Policy Targets) | ||

| Positive (P) | Negative (N) | ||

| Growth shocks (Fiscal Policy Targets) | Positive (P) | PP | PN |

| Negative (N) | NP | NN | |

| POLICY RESPONSE | Monetary Policy Response | ||

| Contraction (C) | Expansion (E) | ||

| Fiscal Policy Response | Contraction (C) | CC | CE |

| Expansion (E) | EC | EE | |

3.3. Data and Variables

3.4. Unit Root Test, Lag Selection Tests and Robustness Check

3.5. Limitations

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Interdependence

4.2. The Set Theoretic Approach

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Adam, C., Alberola-Ila, E., & Tejada, A. P. (2022). COVID-19 and the monetary-fiscal policy nexus in Africa. In BIS papers. Bank for International Settlements. [Google Scholar]

- Afonso, A., Alves, J., & Balhote, R. (2019). Interactions between monetary and fiscal policies. Journal of Applied Economics, 22(1), 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A., & Summers, L. H. (1993). Central bank independence and macroeconomic performance: Some Comparative evidence. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 25(2), 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, R., & Guillard, M. (2019). Interaction between monetary and fiscal policies in the presence of sovereign risk. Economic Modelling, 80, 494–508. [Google Scholar]

- Arby, M. F., & Hanif, M. N. (2010). Monetary and fiscal policies coordination—Pakistan’s experience. SBP Research Bulletin, State Bank of Pakistan, 6(1), 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Aron, J., & Muellbauer, J. (2007). Review of monetary policy in South Africa Since 1994. Journal of African Economies, 16(5), 705–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, J., & Muellbauer, J. (2012). Monetary policy and inflation modelling in a more open economy in South Africa. Economic Modelling, 29(3), 938–956. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, A. J., & Gorodnichenko, Y. (2012). Measuring the Output Responses to Fiscal Policy. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 4(2), 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Barrie, M. S., & Jackson, E. A. (2022). The impact of fiscal dominance on macroeconomic performance in Sierra Leone: A DSGE simulation approach. West African Journal of Monetary and Economic Integration, 22(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, R. J. (1974). Are government bonds net wealth? Journal of Political Economy, 82(6), 1095–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R. J., & Gordon, D. B. (1983). Rules, discretion and reputation in a model of monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 12(1), 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F., & Melosi, L. (2017). Escaping the great recession. American Economic Review, 107(4), 1030–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagrave, P., & Gonguet, F. (2020). Enhancing fiscal transparency and Reporting in India.

- Blanchard, O. (2021). Public debt and low interest rates. American Economic Review, 111(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, O., & Johnson, D. R. (2022). Macroeconomics (8th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Bodea, C., & Higashijima, M. (2017). Central bank independence and fiscal policy: Can the central bank restrain deficit spending? British Journal of Political Science, 47(1), 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buthelezi, E. M. (2023). Impact of government expenditure on economic growth in different states in South Africa. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1), 2209959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantore, C., & Leonardi, E. (2025). Monetary–fiscal interaction and the liquidity of government debt. European Economic Review, 173, 104979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z. (2024). How to coordinate the roles of fiscal policy and monetary policy. GBP Proceedings Series, 1. Available online: https://www.gbspress.com/index.php/GBPPS (accessed on 16 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chatelain, J. B., & Ralf, K. (2020). Ramsey optimal policy versus multiple equilibria with Fiscal and Monetary interactions. arXiv, arXiv:2002.04508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibi, A., Zahaf, Y., & Chekouri, S. M. (2024). Strategic interaction between monetary and fiscal policy in Algeria: A game theory approach. International Journal of Business and Economic Studies, 6(4), 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, J. H. (2001). Long-term debt and optimal policy in the fiscal theory of the price level. Econometrica, 69(1), 69–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, J. H. (2023). The fiscal theory of the price level. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corsetti, G., Dedola, L., Jarociński, M., Maćkowiak, B., & Schmidt, S. (2019). Macroeconomic stabilization, monetary-fiscal interactions, and Europe’s monetary union. European Journal of Political Economy, 57, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, H. R., Montiel, P. J., & Ter-Martirosyan, A. (2021). Macroeconomic stability and inclusive growth. IMF Working Paper. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Debelle, G., & Fischer, S. (1994). How independent should a central bank be? In J. C. Fuhrer (Ed.), Goals, guidelines, and constraints facing monetary policymakers (pp. 195–221). Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Debrun, X., & Jonung, L. (2019). Under threat: Rules-based fiscal policy and how to preserve it. European Journal of Political Economy, 57, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grauwe, P., & Foresti, P. (2023). Interactions of fiscal and monetary policies under waves of optimism and pessimism. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 212, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dery, C., & Serletis, A. (2023). Macroeconomic fluctuations in the United States: The role of monetary and fiscal policy shocks. Open Economics Review. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieye, A. (2020). Overview of current macroeconomic policy issues and challenges in mainstream economics. In An Islamic model for stabilization and growth (pp. 11–47). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englama, A., Tarawalie, A. B., & Ahortor, C. R. (2014). Fiscal and monetary policy coordination in the WAMZ: Implications for member states’ performance on the convergence criteria. In Private sector development in West Africa (pp. 61–94). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z. (2024). Research on the coordination mechanism of fiscal and monetary regulation. International Journal of Global Economics and Management, 4(2), 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, J., Smit, B., & Sturzenegger, F. (2008). South Africa: Macroeconomic challenges after a decade of success. Economics of Transition, 16(4), 639–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Galí, J. (2015). Monetary policy, inflation, and the business cycle: An introduction to the new Keynesian framework and its applications (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Astudillo, M. (2013). Monetary-fiscal policy interactions: Interdependent policy rule coefficients.

- Goyal, A. (2018). The Indian fiscal-monetary framework: Dominance or coordination? International Journal of Development and Conflict, 8(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, B. E. (2000). Sample splitting and threshold estimation. Econometrica, 68(3), 575–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodrick, R. J., & Prescott, E. C. (1997). Postwar U.S. business cycles: An empirical investigation. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 29(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsing, Y. (2020). Does the Mundell-Fleming model apply to South Africa? Journal of Management and Business, 6(2), 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2020). Fiscal monitor: Policies for the recovery. IMF. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2023). Fiscal monitor: On the path to policy normalization. IMF. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2024). South Africa: Staff concluding statement of the 2024 Article IV mission. International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2024/11/26/mcs-south-africa-staff-concluding-statement-of-the-2024-article-iv-mission (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Isah, A., Joseph, T., & Dairo, R. (2022). Review of Ricardian equivalence in theory and practice: Empirical data from Nigeria. Applied Journal of Economics, Management and Social Sciences, 3(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E. A. (2024). Economics of fiscal dominance and ramifications for the discharge of effective monetary policy transmission. SSRN Electronic Journal. Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooste, C., Liu, G. D., & Naraidoo, R. (2013). Analysing the effects of fiscal policy shocks in the South African economy. Economic Modelling, 32, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabundi, A., & Mbelu, A. (2018). Has the exchange rate pass-through changed in South Africa? South African Journal of Economics, 86(3), 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabundi, A., Schaling, E., & Some, M. (2015). Monetary policy and heterogeneous inflation expectations in South Africa. Economic Modelling, 45, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, G. (2011). Exchange-rate regimes and the effectiveness of fiscal policy. Journal of Economic Integration, 26(1), 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kydland, F. E., & Prescott, E. C. (1977). Rules rather than discretion: The inconsistency of optimal plans. Journal of Political Economy, 85(3), 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeper, E. M. (1991). Equilibria under ‘active’ and ‘passive’ monetary and fiscal policies. Journal of Monetary Economics, 27(1), 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. (2025). Can Modern Monetary Theory fit the post-Crisis US facts? Evidence from a full DSGE model. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 30(1), 983–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Mankiw, N. G. (2021). Principles of economics (9th ed.). Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Marire, J. (2022). Relationship between fiscal deficits and unemployment in South Africa. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 15(1), 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T., Ondra, V., & Dominik, K. (2022). The role of fiscal vs. monetary policy in modern economics. Fusion of Multidisciplinary Research, An International Journal, 3(2), 2022. Available online: https://fusionproceedings.com/fmr/1/article/view/40 (accessed on 28 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D. F., De Jongh, J., & Van Wyngaard, D. (2018). An assessment of the effectiveness of monetary policy in South Africa. Acta Universitatis Danubius. Œconomica, 14(6). [Google Scholar]

- Mishkin, F. S. (2019). The economics of money, banking, and financial markets (12th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Montiel, P., & Servén, L. (2006). Macroeconomic stability in developing countries: How much is enough? The World Bank Research Observer, 21(2), 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscatelli, V. A., Tirelli, P., & Trecroci, C. (2004). Fiscal and monetary policy interactions: Empirical evidence and optimal policy using a structural New-Keynesian model. Journal of Macroeconomics, 26(2), 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrullah, M. J., Saghir, G., shahid Iqbal, M., & Hussain, P. (2023). Macroeconomic Stability and Optimal Policy Mix. iRASD Journal of Economics, 5(3), 725–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Treasury of South Africa. (2021). Medium term budget policy statement 2021. National Treasury. [Google Scholar]

- National Treasury of South Africa. (2024). Budget review 2024. National Treasury. [Google Scholar]

- Nuru, N. Y. (2020). Monetary and fiscal policy effects in South African economy. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 11(4), 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboh, V. U. (2017). Monetary and fiscal policy coordination in Nigeria: A dynamic approach. Central Bank of Nigeria Journal of Applied Statistics, 8(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, C. D., & Romer, D. H. (2004). A new measure of monetary shocks: Derivation and implications. American Economic Review, 94(4), 1055–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangweni, S. D., & Ngalawa, H. (2023). Inflation dynamics in South Africa: The role of public debt. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 16(1), 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, T. J., & Wallace, N. (1981). Some unpleasant monetarist arithmetic. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 5(3), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulo, H., Rêgo, L. C., & Divino, J. A. (2013). Fiscal and monetary policy interactions: A game theory approach. Annals of Operations Research, 206(1), 341–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šehović, D. (2013). General aspects of monetary and fiscal policy coordination. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 2(3), 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sharaf, M. F., Shahen, A. M., & Binzaid, B. A. (2024). Asymmetric and nonlinear foreign debt–inflation nexus in Brazil: Evidence from NARDL and Markov regime switching approaches. Economies, 12(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, H. E. (2004). Optimal fiscal and monetary policy with sticky prices. Journal of Monetary Economics, 51(3), 575–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Reserve Bank (SARB). (2010). Annual report 2009/10. South African Reserve Bank. [Google Scholar]

- South African Reserve Bank (SARB). (2020). Our response to COVID-19. South African Reserve Bank. Available online: https://www.resbank.co.za/en/home/publications/publication-detail-pages/media-releases/Our-response-to-COVID-19 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- South African Reserve Bank (SARB). (2022). Monetary and fiscal policy interactions in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. [online]. South African Reserve Bank. Available online: https://www.resbank.co.za (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- South African Reserve Bank (SARB). (2023). Is South Africa falling into a fiscal dominant regime? Working Paper WP/23/02. South African Reserve Bank. [Google Scholar]

- South African Reserve Bank (SARB). (2024). Inflation targeting framework. [online]. Available online: https://www.resbank.co.za/en/home/what-we-do/monetary-policy/inflation-targeting-framework (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Statistics South Africa. (2025). Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS)—Q1: 2025 [Media release]. Pretoria. Statistics South Africa. Published 13 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Stawska, J., Malaczewski, M., & Szymańska, A. (2019). Combined monetary and fiscal policy: The Nash Equilibrium for the case of non-cooperative game. Economic research-Ekonomska istraživanja, 32(1), 3554–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitek, M. F. (2023). Measuring the stances of monetary and fiscal policy. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Woodford, M. (1995). Price level determinacy without control of a monetary aggregate. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 43, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, M. (2001). Fiscal requirements for price stability. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 33(3), 669–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2022). Global economic prospects, June 2022. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2023). Global economic prospects, January 2023: A fragile recovery. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, E. (2024). Coordination of monetary and fiscal policies from a game theoretic perspective. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences, 107(1), 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Expected Sign |

|---|---|

| Monetary Policy | |

| Interest rate lag | + |

| Output gap | + |

| Fiscal policy instrument lag | −coordination/+conflict |

| inflation | + |

| Exchange rate | − |

| Fiscal Policy | |

| Monetary policy instrument lag | −coordination/+conflict |

| inflation | +/− |

| Output gap | − |

| Debt lag | − |

| Government expenditure lag | + |

| Variable | ADF Test Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Output Gap | −5.0991 | 0.0000 |

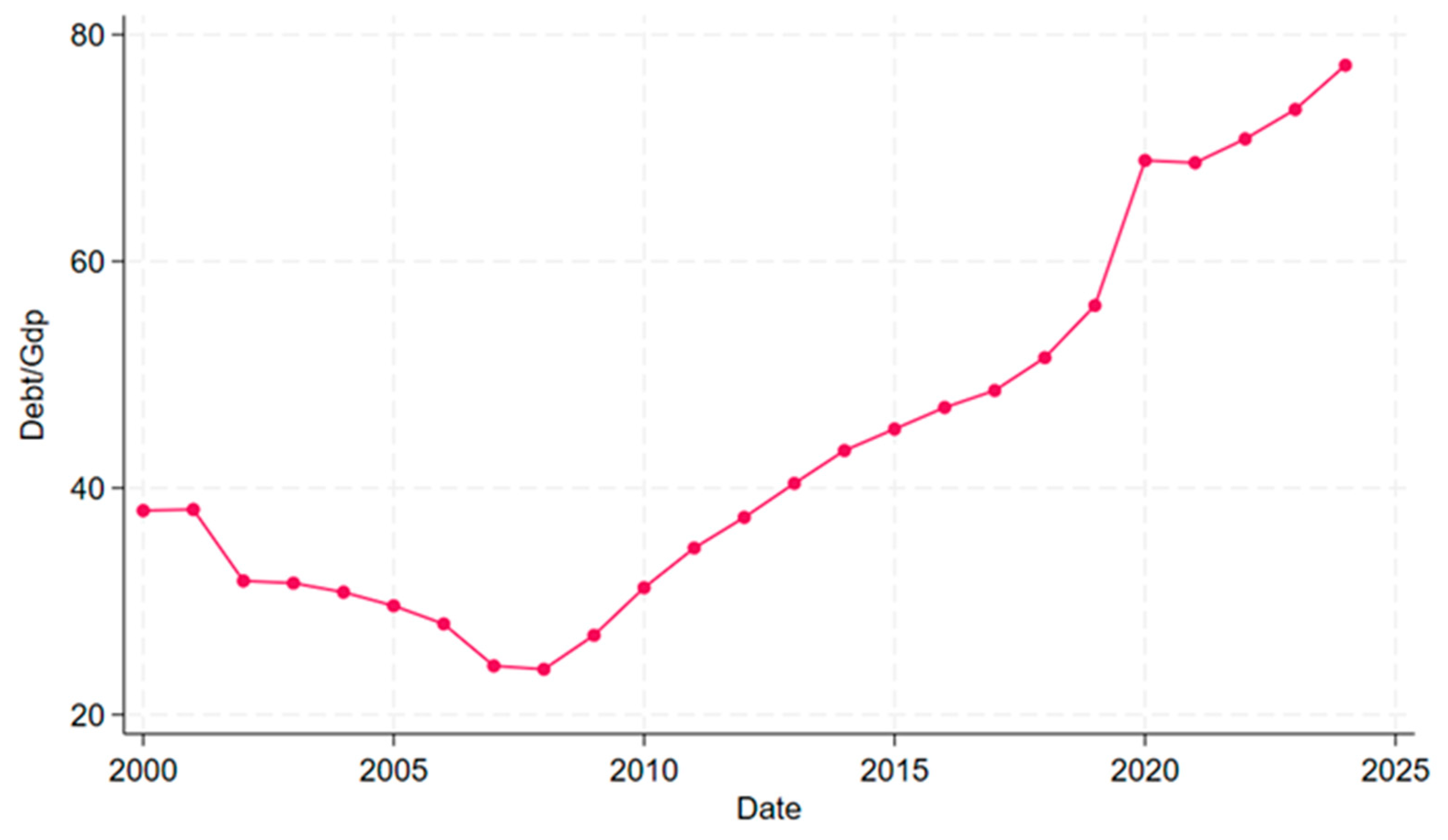

| Government Debt % GDP | −2.7599 | 0.0000 |

| Government expenditure % GDP | −8.0166 | 0.0000 |

| Interest rate | −8.4735 | 0.0000 |

| Inflation rate | −9.1703 | 0.0000 |

| Real effective exchange rate | −11.0458 | 0.0000 |

| Variable | VIF |

|---|---|

| Debt | 1.5458 |

| Government expenditure | 4.9320 |

| Interest rate | 2.1277 |

| REER | 4.1971 |

| Output Gap | 1.0019 |

| Inflation | 1.5149 |

| Dependent Variable: Interest Rate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Coefficients | Standard Error |

| Interest rate −1 | 0.9606 *** | 0.0202 |

| Output gap | 11.6929 *** | 3.1420 |

| Infl | −0.1553 | 0.3183 |

| Gov. Spending | 0.0090 | 0.0236 |

| REER | −0.0573 *** | 0.0156 |

| Dependent Variable: Government Spending | ||

|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Coefficients | Standard Error |

| Gov. Spending −1 | −0.0692 | 0.0835 |

| Output gap | −39.0230 *** | 9.4636 |

| Infl | −1.6809 | 1.0221 |

| Debt −1 | 0.1363 *** | 0.0212 |

| Interest −1 | −0.3161 *** | 0.0627 |

| Variable | Level ADF T-Statistic | First Difference ADF T-Statistic |

|---|---|---|

| Interest rate | −2.5171 (0.1136) | −8.4735 *** (0.0000) |

| Budget deficit | −2.6513 * (0.0854) | −7.6432 *** (0.0000) |

| Null Hypothesis | F-Statistics | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| INT does not Granger-cause DEFICIT | 2.1734 | 0.1178 |

| DEFICIT does not Granger-cause INT | 0.5011 | 0.6070 |

| Dependent Variable | Tau-Statistic | p-Value | Z-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INT | −2.0446 | 0.5130 | −4.8767 | 0.7251 |

| DEFICIT | −2.1686 | 0.4514 | −8.5276 | 0.4089 |

| Variable | Deviation Value |

|---|---|

| Growth (Deviation from sample mean) | 6.35% |

| Inflation (Deviation from threshold) | 4.10% |

| Macroeconomic Targets | Inflation (Deviation from Threshold) | ||

| Positive (P) | Negative (N) | ||

| Growth (Deviation from sample mean) | Positive (P) | A: 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2007, 2008, 2021 | B: 2004, 2005, 2006 |

| Negative (N) | C: 1998, 1999, 2003, 2009, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2022, 2023 | D: 2010, 2020 | |

| Policy Response | Monetary Policy Response | ||

| Contraction (C) | Expansion (E) | ||

| Fiscal Policy Response | Contraction (C) | A: 1996, 2019 | B: 1991, 1992, 1993, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2004, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, 2018, 2020, 2021 |

| Expansion (E) | C: 1990, 1995, 1997, 1998, 2002, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2022, 2023 | D: 1994, 2003, 2005, 2011, 2017 | |

| Years of coordination | 1996, 1998, 2004, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2022, 2023 |

| Years of noncoordination | 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1997, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021 |

| Lag | AIC | SC |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6.8731 | 6.9647 |

| 1 | −0.5745 * | −0.2997 * |

| 2 | −0.4850 | −0.0270 |

| 3 | −0.4207 | 0.2205 |

| Macroeconomic Targets | Inflation (Response to Structural Inflation Shocks) | ||

| Positive (P) | Negative (N) | ||

| Growth (Response to structural growth shocks) | Positive (P) | A: 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994 | B: 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023 |

| Negative (N) | C: | D: | |

| Policy Response | Monetary Policy Response | ||

| Contraction (C) | Expansion (E) | ||

| Fiscal Policy Response | Contraction (C) | A: 1996, 2019 | B: 1999, 2000, 2001, 2004, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, 2018, 2020, 2021 |

| Expansion (E) | C: 1990, 1995, 1997, 1998, 2002, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2022, 2023 | D: 1994, 2003, 2005, 2011, 2017 | |

| Years of coordination | 1999, 2000, 2001, 2004, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, 2018, 2020, 2021 |

| Years of noncoordination | 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2011, 2017, 2019, 2022, 2023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mavundla, A.; Nyati, M.C.; Msomi, S. The Coordination of Monetary–Fiscal Policy in South Africa. Economies 2025, 13, 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100280

Mavundla A, Nyati MC, Msomi S. The Coordination of Monetary–Fiscal Policy in South Africa. Economies. 2025; 13(10):280. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100280

Chicago/Turabian StyleMavundla, Amanda, Malibongwe Cyprian Nyati, and Simiso Msomi. 2025. "The Coordination of Monetary–Fiscal Policy in South Africa" Economies 13, no. 10: 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100280

APA StyleMavundla, A., Nyati, M. C., & Msomi, S. (2025). The Coordination of Monetary–Fiscal Policy in South Africa. Economies, 13(10), 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13100280