Abstract

This study focuses on tax evasion within the framework of earmarking taxation, specifically focusing on the evasion of car ownership taxes. We utilize a unique and extensive micro-database that combines information on regular payments of the tax due, late payments following friendly warnings, and non-payment of vehicle ownership taxes, integrated with fiscal data, individual data, and municipal-level data. The empirical analysis examines individual, socio-economic, and institutional factors related to this issue. Drawing a rich dataset from the 2014 Tuscany car tax, we employ a multilevel logistic model for our empirical investigation. Our findings reveal that tax evasion poses an equity problem, as the inclination to evade vehicle ownership taxes is concentrated among specific demographic categories and types of vehicles. We also suggest that regional-level policies, such as friendly warnings, could be more effective if implemented with greater rigour. Lastly, our results indicate that reinforcing civic responsibility and enhancing institutional and political quality could prove particularly beneficial in enhancing tax compliance.

Keywords:

vehicle ownership tax; earmarking taxation; compliance; evasion; friendly warnings; institutional quality; behaviour; regional taxation JEL Classification:

H26; H71; C2

1. Introduction

Vehicle ownership tax is a widespread form of taxation in many European countries. This form of taxation is commonly used as an environmental and earmarked tax aimed at internalizing externalities derived from transportation. In many countries, earmarked taxes are collected to contribute to local governments’ revenues due to the increased accountability in resource utilization, and a higher level of compliance for this type of taxation.

The literature has shown increasing attention to earmarked taxation and its effect on consumer behaviour and emission reduction. A growing number of studies are looking at the effect of carbon taxation on passenger vehicle sales and usage, for example (see, e.g., Alberini et al. 2018; Alberini and Bareit 2019; Alberini and Horvath 2021; Cerruti et al. 2019). Most of these studies show that modifying the vehicle registration tax and linking it directly to carbon emissions has proven to be effective in switching individuals’ preferences toward less polluting vehicles (e.g., Alberini and Bareit 2019; Cerruti et al. 2019). Furthermore, in the context of durable goods, “new car registrations react to tax cuts and fee-bates significantly more than to tax increases” (see Soldani and Ciccone 2019, p. 1).

Other authors have also focused on the effect of earmarking taxation on tax compliance, claiming that direct democracy, decentralization and earmarked taxation can foster tax compliance (Schaltegger and Torgler 2008; Torgler et al. 2010). In a controlled lab experiment, Brockmann et al. (2016) show that governments can increase tax compliance by rewarding honest taxpayers, though the effect seems to affect only females, thus suggesting there is no “one-size fits all” approach to boost tax compliance. Recent development in the literature seems to suggest that earmarking taxation can increase taxpayers’ compliance by enhancing the ‘procedural utility’ (see Frey and Stutzer 2005 for a discussion) of paying taxes. According to Brockmann et al. (2016), this can be achieved via two different mechanisms: (1) earmarking taxation raises taxpayers’ awareness of the potential usefulness of their tax payment; and (2) this opportunity allows taxpayers to actively participate in policy decisions by making them policy-makers rather than policy-takers1.

This paper gives a contribution to that part of the literature that analyses why people choose to engage in tax evasion in the context of earmarking taxation that is regionally administered. In this case, citizens’ involvement in policy choices is greater, and non-payments can be promptly identified by the tax administration2. Our paper focuses on car tax compliance in the Italian region of Tuscany, though vehicle ownership taxation in Italy applies to all vehicles and motorcycles registered within the country’s borders. We use a unique dataset collected in Tuscany over the fiscal year 2014 to identify factors affecting tax dodgers’ behaviour. The dataset gathers car tax information, car characteristics and car owners’ socio-demographics.

In Italy, vehicle taxation represents an important source of tax revenue. Indeed, the tax applies to 52 million vehicles, of which more than 40 million are cars in 2022. The tax has been introduced in 1953 to finance road construction and maintenance costs and it is currently a pillar of local taxation. Italian regions administer the tax and are responsible for enforcing compliance. The tax is levied annually based on the vehicles’ engine power (measured in kW), age and pollution emissions.

Car ownership taxation in Italy is extremely unpopular among taxpayers. Although it is easy to assess thanks to a national vehicle register, the level of tax evasion is significant (13% at the national level in 2014)3. However, this figure is difficult to quantify with certainty, given the high proportion of late payers and the ineffectiveness of enforcement procedures, which varies from region to region. For example, in the region of Tuscany, with 3.7 million inhabitants, 3.8 million vehicles and 2.5 million cars, almost 20% of the tax due was not paid on time in 2014, and this has not changed significantly to date (Baldaccini 2023). In Emilia-Romagna, a region close to Tuscany in geographical and socio-economic terms, tax evasion was estimated at 9% for 2015–2016, with late payers and evaders accounting for more than 40% (Corte dei Conti 2022).

Whilst a vast amount of literature explores the impact of tax morale on individuals’ behaviour (Torgler 2007; Luttmer and Singhal 2014), and estimates the size of the shadow economy (Ahumada et al. 2007; Schneider 2000; Schneider and Buehn 2013), to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first empirical study on taxpayers’ behaviour in the context of vehicle ownership taxation, based on a large dataset on individuals’ characteristics and extensive information at municipal level.

The ‘economic’ analysis of the decision to evade taxes was pioneered in Allingham and Sandmo’s (1972) paper on optimal tax declaration, where individuals consider the net benefits of evading taxes to maximize their expected utility. However, for all the merits of this approach, there are important limitations to the model. First, the model considers the taxpayer as a rational individual, who makes decisions only to maximize their own utility. However, according to Spicer and Lundstedt (1976), the decision to evade taxes does not depend merely on the associated utility, but also on moral aspects and taxpayers’ attitudes towards illegal crimes. Erard and Feinstein (1994b), for example, suggest that moral sentiments drive tax compliance. This indicates that the reasons for taxpayers’ compliance must be sought not only in the economic sphere, but also in the psychological and moral spheres (Bott et al. 2020). Recent developments in neuroscience also provide a foundation of the relevance of moral sentiments for tax compliance (Dulleck et al. 2016). Alongside individual attitude, the social environment and moreover the governance and institutional quality also have importance (Torgler and Schneider 2007). Trust in institutions and transparency regarding the direct use of taxation may encourage compliance, thereby enhancing the provision of public services (Marien and Hooghe 2011).

Our paper contributes to the literature studying the drivers of tax compliance and the relationship between taxpayers and institutions. In this work, we base our analysis on a comprehensive micro-database, which allows us to clearly identify several characteristics of tax evaders. We integrate this individual dataset with an extensive set of information at the municipal level. Another advantage of our setting is that the micro-database collects individual information on regular/late payments after friendly warning/non-payment of vehicle ownership tax in Tuscany. This is particularly valuable when results in the literature are mixed, as is the case for interventions appealing to friendly warning messages (Bott et al. 2020; De Neve et al. 2021). Moreover, there is growing interest on the use of “nudges” to prevent tax evasion, being this seen as a more effective intervention than punishment. This paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents some preliminary data analysis on individual car ownership tax in Tuscany. Section 3 discusses some implications of the Allingham and Sandmo (1972) model and compares expected and experienced car ownership tax evasion in Tuscany. Section 4 presents empirical results. Section 5 briefly discusses the results and concludes.

2. Car Ownership Tax in Italy: Trends and Perspective

Amongst the EU Member States with the highest motorization rates in 2022, Italy ranks first, followed by Luxembourg, with 682 cars per thousand inhabitants (vs. 673 cars per thousand inhabitants in Luxembourg). The Italian motorization rate shows a certain variability between geographical areas, but Tuscany stands out with a very high motorization rate.

All EU countries levy taxes on vehicle ownership, which have increasingly been used to influence driver behaviour and encourage the purchase of low-polluting or more fuel-efficient vehicles. Although the tax base characteristics are quite homogeneous across countries (and based on engine power and emissions), the tax rates vary widely. In Italy, the tax is paid annually by anyone who owns a vehicle registered in the Vehicle Public Registry (Pra). The tax due on cars is based on engine power, expressed in kW/m3, and on environmental classes, so it is higher for cars with high environmental impact and indirectly operates as an environmental levy4. The Italian vehicle ownership tax is administered at a regional level, but with a limited degree of discretional power, which means that the Italian regions can make only minor changes to the basic tax rate and introduce specific exemptions. Tax collection is a regional task, so regional governments are also responsible for strategies to encourage tax compliance. The vehicle ownership tax in Italy was equivalent to more than EUR 7 billion in 2022, representing on average about 13% of total regional revenues.

Despite perfect information on vehicle ownership, there is a significant prevalence of tax evasion for this earmarked taxation in Tuscany, similar to what can be found in other Italian regions.

Car Ownership Tax in Tuscany: Descriptive Statistics and Context

Table 1 presents the vehicle distribution, based on tax due, regular and late payments, and evaded tax for 2014, our year of analysis. We work with this specific year as it is the only period in which we have availability of complete information about car tax and taxpayers. The due revenue in 2014 was EUR 502 million, of which only 340 million was collected in due time and 63 million as late payments. More than 98 million (19.6%) can be classified as tax evasion. It is interesting to note that cars—72% of the vehicles in the region—account for 86% of total tax evasion.

Table 1.

Evasion and compliance for vehicle type in Tuscany (2014), in EUR (millions).

We can categorize the taxpayers as follows:

- Regular: those who paid in due time.

- Late payers: those who have paid after a request for payment (friendly warning).

- Evaders: those who have not paid tax (starting from 6 months after the due date, considered an unwanted delay).

In the same way, we can categorize the amounts of payments, with the sum of regular payments, late payments and evaded amounts representing the total tax due.

Given the high level of tax evasion characterizing a specific subset of homogenous taxpayers, i.e., car owners, we focus our analysis on taxpayers owning at least one car and residing in Tuscany5. After excluding incomplete observations, our final dataset consists of 1,485,283 individuals owning 1,693,083 cars. The dataset comprises information on car features, individuals’ socio-economic and demographic characteristics (at individual and aggregate levels), and economic and institutional aspects of the local municipality6.

The unpaid amount represents 18% of the tax due, for a total of 13% of tax evaders (see Table 2). This shows how widespread the phenomenon is, despite available information on car ownership taxation and specific nudges (such as friendly warning letters)7 put in place by the local authorities. We also observe that this phenomenon is primarily concentrated among individuals with the highest tax liabilities, many of whom own high-performance vehicles.

Table 2.

Breakdown of taxpayers and tax revenue (cars only, excluding incomplete observations).

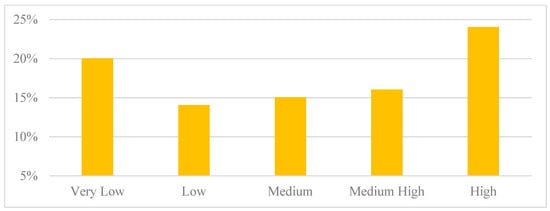

We therefore consider the relationship between tax evasion and income (see Figure 1) and note that higher tax evasion is concentrated both in the first and in the last car tax quintiles (24%). This seems to suggest a U-shaped relationship between the value of the car and the car tax evaded.

Figure 1.

Incidence of car tax evasion by car tax quintile.

Observing the car owners’ distribution of regular and late payers in relation to income quintiles (see Figure 2), the data show that the share of car owners paying in due time increases with income, while the percentage of evaders and late payers decreases with income. However, it is worth noting that for most tax evaders, income data are not available8. We hypothesize that this lack of information could stem from either a correlation between undeclared income and evasion of car taxes or the possibility that many of these taxpayers had no taxable income, being among the poorest segment of the population. This being said, the share of car tax evaders in the group of ‘not-available’ income is much higher than in the overall sample (28% vs. 13%; see Table 2).

Figure 2.

Taxpayer composition for income quintile. Note: I–V represent different income quintiles (in Roman numbers), and NA stands for ‘not available’ income information.

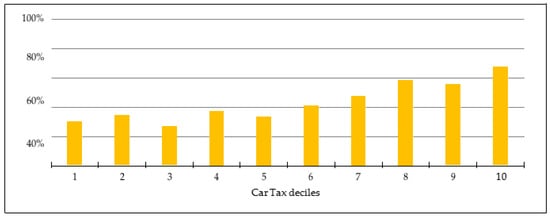

Considering the sample of ‘no-available-income’ taxpayers (i.e., those who are liable for the car tax but are not reporting annual income), as expected, there seems to be a direct link between the car tax due and tax evasion. That is, taxpayers who are due to pay the highest car tax are also those who evade it the most. Presumably, some of these taxpayers are also dodging their income tax and own the most expensive and high-performance vehicles. Figure 3 shows that in the highest car tax decile, corresponding to an average tax of EUR 498, tax evasion reaches a peak of 67%, which is the highest level across all car tax deciles.

Figure 3.

Share of tax evasion for car tax deciles (no-available-income subset).

This evidence highlights that further investigation is needed to better understand the decision to participate in tax evasion in the context of earmarking taxation.

3. Expected and Experienced Tax Evasion

The seminal Allingham and Sandmo (1972) model of tax evasion (hereafter ASY model)9 describes the trade-offs a taxpayer faces when making the decision to evade taxes. This approach requires for the taxpayer to know with certainty the probability of being audited, p.

Based on our classification of compliance behaviour,10 we can consider different expected loss functions, L(T), per type of taxpayer:

- Regular taxpayer: L(T) = T;

- Taxpayer with late payments: L(1 + DT);

- Evader: L(T + 0.3T) or L(1.3T) if caught; L(T) = 0 if not caught,

where T is the due tax and D the fine for late payments equal to 1% or 3,75% depending on the delay (D = 0.01 or 0.0375); for tax evaders, there is a fine equal to 30% applicable to the undeclared car tax, which in this context equals the tax due.11 For simplicity, we assume a linear (or quasi-linear) relationship between L and T. This suggests that if the taxpayer is not caught by the tax authority, L(T) = 0, i.e., the expected loss is equivalent to zero. By contrast, if caught, the loss function will be given by L(1.3T), i.e., the loss is a function of the tax that the individual has to pay, plus a fine (=30%*T). The expected loss E(L) of the taxpayer will therefore depend on a probability p of being caught by the tax authority:

If we compare Equation (1) with the expected loss of the honest taxpayer, E(L) = L(T) = T, and under the standard assumption that an individual will pay taxes honestly if the expected loss from paying taxes honestly is smaller than that expected loss by acting dishonestly, we can then rewrite (1) as follows:

Rearranging (2) and solving for p, in our study, we find that for p 76.92%, it is convenient to pay the fine on time, while for lower probabilities, it is convenient to evade. This is in line with predictions of the ASY model, though it seems to suggest very high levels of tax evasion than those found in the real world (for a discussion, see, e.g., Weber et al. 2014).

Second, the result discussed above reveals interesting insights on how people form expectations on audit probability. For the car tax discussed here, on the one hand, the probability of detection is almost 100%; thus, the conventional ASY tax evasion model would suggest zero tax evasion. On the other hand, given that after receiving the friendly warning letter, the fine increases up to 300 times, one would expect the vast majority of taxpayers to comply within six months to one year from the missed deadline. Nevertheless, only 38% of those who failed to meet the initial deadline paid after the friendly warning (mostly just late payers), with the remaining 62% being tax evaders. Two important aspects are worth noting here. First, even though the tax administration in Italy can promptly identify the car owner, tax evaders appear perceiving the probability of detection and actual prosecution as being very low (or equal to zero). Perhaps, taxpayers act under the rooted assumption that they will not be prosecuted by law and think that they will obtain greater benefit by evading taxes. Second, the use of a friendly warning message in this context seems to be only partially effective. The letter, in fact, has the potential to signal high probabilities of coercive procedures as it revealed that taxpayers’ liability can be identified and monitored. In the case of further non-payment, additional punishments are also applicable.12 However, our data seem to suggest that individuals who pay the car tax after receiving an early warning are predominantly late payers (and might have paid the tax regardless), raising questions about the efficacy of this intervention on tax evaders.

This result is in line with Galmarini et al. (2014), who find that receiving a notice from the tax authority is not effective in reducing tax evasion, thus suggesting that more efficient ways to enhance tax compliance would include reinforcing the strength of the warning, e.g., by making the names of those who refuse to pay publicly available13 (exploiting reputational costs) or making it more difficult for those who evade taxes to access bank loans (reporting tax evaders to banks).

Recent developments in behavioural public policy also suggest that a nudge (such as a friendly warning letter) could become more effective and legitimate if incorporating an element of reflection (the plus), potentially leading to long-term, consistent, and sustainable behaviour change (Banerjee and John 2024). To give an example, in the context of earmarking taxation, a nudge plus could be implemented by adding to the friendly warning message an explanation of how taxpayers’ individual contributions will help finance specific projects.

Going back to our study, an increase in the penalty rate above the current 30% (which seems not to be a deterrent for tax evaders) may also be desirable. Cranor et al. (2020), for example, using data from Colorado on the tax year 2015, show that sending reminders with information about ‘progressive’ (and increasing with delays) financial penalties14 to tax delinquents may have a stronger impact on tax compliance than sending messages highlighting the relevance of social norms. The authors conclude that ‘attention to seemingly minor decisions about the wording of notices’ might have important consequences on taxpayers’ compliance behaviour (Cranor et al. 2020, p. 331). Furthermore, a related recent study suggests that communication that manipulates the taxpayers’ perception about the likelihood of an audit can also help in improving tax compliance (see, e.g., Mazzolini et al. 2022; Carfora et al. 2018; Gangl et al. 2014; Castro and Scartascini 2015; and, more recently, Bott et al. 2020). Under the ASY model, the decision to evade taxes is modelled considering taxpayers’ payoffs, pondered with the adverse event of a tax audit. This approach requires taxpayers to know their probability of being audited. This is a very strong assumption considering that in real life, it is widely expected that this probability is unknown to the taxpayer. Schmeidler (1989) states that the formation of individual probabilities leads to an incorrect estimate of the probability itself, which, instead of reflecting the frequency of the event, reflects the subject’s confidence level, thus providing probability estimates that do not add up to one. Similarly, Snow and Warren (2005a, 2005b) and Dhami and Al-Nowaihi (2007) suggest that, under uncertainty, risk aversion leads individuals to severely overestimate the probability of a tax audit, thus becoming more compliant. However, the opposite is true for risk lovers (i.e., they become less compliant). Therefore, according to (Snow and Warren 2005a, 2005b), given that governments cannot screen taxpayers based on their risk aversion, it might be not advisable to foster uncertainty as a policy tool to boost compliance.

Our findings imply that taxpayers’ confidence in evading taxes without facing legal repercussions appears to be significant and likely reinforced over time. Indeed, tax evasion tends to be recurrent (Angeli et al. 2023), suggesting that a more proactive policy in this regard could prove effective in the Tuscany context.

4. Data and Empirical Strategy

Having established some interesting aspects of earmarking taxation and individuals’ tax compliance, this study seeks to understand the impact of some socio-economic and environmental factors that affect the decision to evade earmarking taxation.

4.1. The Dataset

For the analysis, we consider a comprehensive dataset on car tax in 2014. The base unit for the analysis is a single taxpayer who owns one or more vehicles. In total, our dataset consists of 1,485,283 individuals for 2014. Motorbikes have been excluded from the sample. We focus our analysis on cars as they represent a large proportion of the vehicles included in the database. In addition, people may have different tax attitudes/behaviours when considering different vehicles. We also excluded taxpayers who did exhibit ambiguous behaviour toward vehicle taxation from the sample, e.g., paying the tax for one vehicle but not for another. The dataset is built using a combination of different sources, including the Public Register of vehicles (PRA), which reports data on vehicles for which the car tax is due; the Italian Automobile Club (ACI), which is the institution in charge of collecting car tax; and the National Statistical Office and Regional data on taxpayers. Aside from the binary variable describing taxpayer behaviour, we can distinguish four core macro areas, covering the most common determinants of tax evasion that we collect at the individual, fiscal and municipal levels. These include the following:

- Socio-economic and demographic variables. An extended literature studies the effects of individual characteristics on individual propensity to evade (see, e.g., Alm and Torgler 2006; Halla and Schneider 2008, 2014; Torgler and Valev 2010). Results are mixed, but in general, variables such as age, gender, marital status and income can be crucial in predicting taxpayers’ compliance and risk attitudes, under the standard assumption that risk-loving individuals are also more inclined to commit fraudulent acts.

- Variables associated with car characteristics (e.g., present car value, number of cars owned by a taxpayer, car tax and age). These are used to investigate the relationship between the car value and the tax due, and to test whether the car depreciation has a negative impact on tax compliance. A proxy of the present value of the car is calculated considering the linear link between the car tax, the value of the car, and the effective tax rate (ratio between the car tax and the actual value of the car): the effective tax rate increases as the car value depreciates. Therefore, we consider this effective tax rate as the ratio between the nominal car tax and the depreciation factor for the car. This is provided as follows:where CT is the car tax, ECT the effective car tax rate, i represents the car depreciation rate, and n is the car age. This variable captures the individual’s lower propensity to pay the tax due to the car depreciation. The car tax here is used as a proxy for the present car value.

- Economic environment variables. Collected at the municipal level, these variables proxy the local economic situation faced by different taxpayers. The objective here is to investigate whether wealthier areas of Tuscany are less likely to engage in tax evasion. The literature shows that subjects with high tax compliance are also those who receive benefits from the welfare system, e.g., elderly and most educated people (Rodriguez-Justicia and Theilen 2018). Experimental and survey evidence support the conclusion that citizens are more willing to pay taxes if they receive public goods and services in return (see, e.g., Torgler 2002). More deprived areas may also offer fewer public goods and services, which may lead individuals to evade more taxes. To test whether tax evasion is concentrated in deprived areas of Tuscany, we consider a set of variables as indicators of the local economy. These are the car owners’ income source (taken from the car owner and fiscal datasets and captured by the percentage of individuals with different occupational statuses on total residents), the number of firms per capita and the percentage of firms in the tertiary sector. We finally include the average taxpayer income (municipal statistics).

- Institutional variables. These are included to capture the relationship between the taxpayer and public (regional) administration and proxy the quality of the local institution. Both aspects play an important role in increasing tax compliance (see, e.g., Nicolaides 2014; Hallsworth et al. 2017; Alstadsæter et al. 2018). Considering quality, Torgler and Schneider (2007) show that lower levels of tax evasion are obtained when citizens trust both central and local governments, and even more so when the latter approves the choices in the field of public finance (Buehn et al. 2013). The institutional approach suggests that high institutional quality and open government initiatives enhance tax revenue and compliance by legitimizing tax burdens and expenditures and encouraging open participation in policy and law-making processes (Khaltar 2024). Earmarking taxation can strengthen the legitimacy of the tax burden by providing transparency, ensuring accountability and demonstrating that tax revenues are being used effectively for specific purposes. This process can build and maintain trust in governments, leading to greater tax compliance and a more positive relationship between taxpayers and institutions (see, e.g., Torgler and Schneider 2007). However, the literature also suggests that the greater the (physical and political) distance from the centre of power, the greater the level of tax evasion, as taxpayers may feel they are not engaged with the decision-making process (Pukeliene and Kažemekaityte 2016; Buehn et al. 2013). Moreover, complex tax systems may lead to higher levels of tax evasion (Pukeliene and Kažemekaityte 2016; Daude et al. 2013). This suggests that the tax collection agency must work in a transparent and cooperative manner with the taxpayer to boost taxpayers’ confidence in the government (Lisi 2014). Taxation transparency has proven to be particularly important to enhance tax compliance (see, e.g., Johannesen and Larsen 2016), and might be particularly relevant for earmarking taxation given that people may be more willing to pay taxes if they know how their money is being used (Seely 2011; Perez-Truglia 2020). We proxy the complexity of the regional administration with the regional political fragmentation represented here by the number of parties in the municipalities. In addition, we include variables such as the local municipal tax burden (proxied by the per capita average tax burden per municipality), and specific municipal budget items such as investments in transport and fixed public expenditures to capture the flexibility/rigidity of local public expenditures, which justifies earmarking taxation as a designated budget to finance specific public services. We also use the geographical distance from Florence, the chief town of Tuscany, to capture the perceived distance from the central decisional government.

- Moving to the relationship between citizens and the public authority, we include variables related to civic participation, such as the presence of volunteers (i.e., the percentage of individuals engaged in charity activities per municipality) and individuals’ participation in elections (municipal dataset) to capture citizens’ identification and participation with the local governments. The literature suggests a positive relationship between civic duty and moral attitudes to tax evasion (see, e.g., Orviska and Hudson 2003). Therefore, we expect that higher levels of participation in local government activities are also associated with lower tax evasion, mediated by moral factors.15

All variables used in the empirical analysis are reported in Table A1 in Appendix A.

4.2. The Empirical Strategy

Our data involve different levels of aggregation (i.e., individual and municipal levels). Therefore, we consider a simple random intercept logistic regression as our empirical strategy. A multilevel model will allow us to simultaneously quantify the impact of individual characteristics on tax compliance and better understand how groups’ heterogeneity in different municipalities affects the decision to evade taxes. The model is described below:

where is the dependent variable, i represents the i-th individual of group j, is the intercept, is a matrix of individual explanatory variables also called independent first-level variables with the coefficient vector given by , is a group or second-level variable matrix with coefficient , and are first-level residues or individual residues. The randomly intercepting multilevel structure is given by the second system equation. The intercept is given by a constant, and a random component that varies from group to group and that is called the second-level or group residue.

The dependent variable is a dichotomous variable that takes on a value of 1 if the individual has not paid the tax, and 0 otherwise. Table 3 below reports regression results.16 Calculations were performed in STATA14 using the milogit routine.

Table 3.

Results for logistic multilevel regression.

The results provide us with a clear picture of tax compliance and evasion relating to car ownership taxes in Tuscany. As expected, there are four key drivers of car tax evasion grouped in the macro-areas listed below:

- Car characteristics (at the individual and aggregate levels).

- Economic environment variables (averaged at the municipal level).

- Socio-economic and demographic variables (at the individual and aggregate levels).

- Institutional variables (averaged at the municipal level).

As discussed in Section 2, the car tax has a negative effect on tax compliance with higher levels of taxation corresponding to increased willingness to evade. Similarly, the effective car taxation plays an important role on the decision to evade the tax: when the car depreciates and/or becomes older, tax compliance decreases. It is interesting to note that as taxpayers with several cars tend to be more compliant, probably because of a higher ability to pay.

Civic duty is a significant element in explaining taxpayers’ compliance since municipalities with a higher level of volunteers and participation in elections are less likely to evade. The political fragmentation of the city council, proxied by the number of parties, is also significant: scarce identification with political parties and local government leads to a greater aversion to paying car tax. This is particularly relevant when considering the nature of earmarking taxation. Tax earmarking can mitigate agency problems in public provision, fostering accountability and creating a more direct linkage between private monitoring choices and taxes paid (Dhillon and Perroni 2001). Losing this direct link due to lack of identification with the local government may lead to higher resistance to earmarking taxation.

The effect of individual characteristic emerges clearly from the results, with the elderly, women, and families not surprisingly complying more often than others with their obligations (see, e.g., Barile et al. 2022; Halla and Schneider 2008, 2014).

Among the socio-economic and demographics variables, households’ income and occupational status play a significant role on the willingness to evade taxes (at the individual level). According to the literature, as per other types of income taxation (see, e.g., Torgler and Valev 2010), higher levels of car tax evasion are present among the self-employed, while, as expected, retired people and employees have higher levels of tax compliance. Moreover, in line with what was discussed in Section 2, higher income levels correspond to lower evasion (see Figure 2), while ceteris paribus, no-available-income taxpayers are significantly more likely to engage in tax evasion (by approximately 20%).

A greater propensity to evade taxes is found among foreigners, possibly attributed to their lower incomes, or less familiarity with the tax system.

Looking at the aggregate economic environment variables, industrial areas seem to be less likely to engage in tax evasion. However, different occupational statuses and average household incomes have limited influence on tax compliance, with the percentage of employed and unemployed individuals per municipality only being significant at the 10% level (with income and all other occupational variables remaining insignificant).

The results also suggest that public infrastructures play a role in determining taxpayers’ behaviour, with higher investments in public transport being positively correlated with higher levels of tax compliance. This confirms previous findings in the literature (see, e.g., Buehn et al. 2013): when taxpayers see a return on the amount of taxes paid, they are also more likely to contribute to the public budget. Interestingly, local taxes do not seem to have a significant effect on the willingness to evade the car tax. Note that this result may also be due to the high level of correlation between higher tax burden and public transport investments, with the former being the strongest predictor for tax compliance. In fact, the higher the public revenue (collected via taxation), the greater the investments in infrastructure.

In addition, the distance from the regional capital, Florence, significantly and positively affects the willingness to evade. Further investigation of the data shows that the areas that appear to be distant from Florence, and, in particular, those in the coastal area have a higher level of evasion (see also Section 2). This is in line with the work by Pukeliene and Kažemekaityte (2016), who assert that those living at a greater (geographical or psychological) distance from central governments tend to be reflected less often in government choices, and thus tend to evade more.

In general, many of these factors can be traced back to the concept of institutional quality, understood as civic virtue, and the ability of the administration to respond to citizens and politics’ linkage with citizens. This is an interesting result of our work, which suggests that besides socio-economic and demographic variables collected at the individual level, in the context of earmarking taxation and regional administration—the focus of this analysis—proximity to the political and administrative centre and civic participation are important factors for individuals’ willingness to evade tax. Finally, institutional quality of local administration is found to be a boost towards a collective awareness and civic participation.

4.3. Predicted Probabilities and Car Tax Evasion

We consider predicted probabilities to evaluate the effect of different factors on the decision to evade car tax. For comparison, we consider 12.9% as the average probability of evading car tax (see Section 2).

To account for differences in risk attitudes, we compare four different groups of taxpayers, who, according to the literature and the results described in Section 4.2, may exhibit different attitudes towards tax evasion.

These taxpayers differ by gender and age. In particular, we compare women and men aged 35 or 65 years old. The literature indicates (for example, Borghans et al. 2009) that women exhibit greater levels of risk aversion compared to men, while older individuals tend to opt for less risky decisions when contrasting their life cycle choices with those of younger generations (Tymula et al. 2013). We compare the expected probability to evade the car tax for all four groups. The results are reported below.

| Young Woman | Young Man | Av. Probability | Aged Woman | Aged Man |

| 19.38% | 23.50% | 12.89% | 5.47% | 5.01% |

As expected, the results show that a risk-loving person (i.e., a taxpayer in their younger years) is more likely to engage in tax evasion (differences vary between 14 and 18 percentage points for women and men, respectively)17. This pattern is exacerbated with age. Women are more risk averse than men, but only when in their younger years. In fact, among the elderly, we find a higher level of tax compliance for males. As per Tymula et al. (2013), this phenomenon could stem from either increased risk aversion among older individuals or a heightened sense of civic duty, which may grow with age as individuals gain wisdom.

As discussed in Section 4.2, civic duty, captured by individuals’ engagement with the local administration, plays an important role in our analysis. Communities actively engaged in public life tend to align more closely with political decisions and consequently adhere to taxation principles, actively contributing to public goods. Spatial clustering further supports the perspective of Erard and Feinstein (1994a, 1994b) regarding the contextual significance in shaping individual evasion behaviours, heavily influenced by imitative tendencies. We consider the predicted probabilities of those with high/low civic participation. Our results confirm that taxpayers belonging to municipalities with lower civic participation (first quartile of the distribution) have a 5.3% higher chance of not paying car tax.

| High Civic Virtue | Av. Probability | Low Civic Virtue |

| 11.02% | 12.89% | 16.32% |

The literature indicates that a stronger sense of civic duty may be associated with higher quality of local or central institutions (for example, Torgler 2003) fostering a trusting relationship between the government and citizens, who may feel represented in their preferences. Likewise, living near the central administration may positively influence tax compliance, as citizens may feel more involved in the decision-making process (see, e.g., Pukeliene and Kažemekaityte 2016). We therefore analyze different levels of evasion in municipalities with different institutional quality and consider comparing the 25% of municipalities with high institutional quality against the 25% with low institutional quality. To rank municipalities by institutional quality, we take into account investments in transport, and the distance from the regional capital, as the analysis in Section 4.2 shows a greater propensity to evade taxation in municipalities not in the proximity of Florence (referred to in the literature as a measure of “power distance”, i.e., the perceived distance from decisional centres). The results confirm that areas closer to central administration and with better infrastructures show a lower level of evasion than those in peripheral areas.

| High Institutional Quality | Av. Probability | Low Institutional Quality |

| 10.58% | 12.89% | 15.03% |

We finally consider the impact of tax due on the probability of evading taxes. Our analysis in Section 4.3 suggests that higher taxation is associated with more tax evasion. We compare here the highest tax quintile, with amounts of tax due exceeding EUR 665, and the second quintile, with amounts between EUR 93 and 255.18 The findings indicate a higher likelihood of evasion for exceptionally large tax amounts, with taxpayers evading at more than double the average rate. Conversely, the second quintile of tax amounts, representing the majority of taxpayers, exhibits a non-compliance rate slightly below the average.

| Low Tax Amount | Av. Probability | High Tax Amount |

| 11.01% | 12.89% | 26.48% |

5. Conclusions

Despite the fact that car ownership non-compliance is easily identifiable by the local government, a significant proportion of the tax continues to be evaded by taxpayers in the Italian region of Tuscany. This paper identifies and discusses important factors affecting the decision to engage in vehicle tax evasion, an earmarked levy financing regional governments. These factors encompass socio-economic demographic attributes of taxpayers, characteristics of vehicles, and economic environmental factors, as well as the quality of local institutions and citizens’ sense of civic responsibility. The empirical analysis corroborates some existing results in the literature showing that tax evasion varies within different groups. Those who are typically characterized by high risk aversion exhibit greater reluctance towards tax evasion, notably the elderly and women. Along with individual socio-economic demographic characteristics, our analysis also indicates that institutional quality and a sense of city duty play an important role in increasing tax compliance (Allam et al. 2023). In addition, our findings suggest that tangible returns in the form of public services and investments from the administration, coupled with the perception of having a greater influence on decision-making processes, can enhance citizen compliance. In future studies of this line of research, it would be very interesting to replicate the estimated model in other Italian areas, as the car ownership tax is very unpopular and the level of evasion of this tax is estimated to be very high in all areas of the country. At present, however, data on evasion and enforcement are very limited, both at the national level and for individual regions.

In this paper, we also consider the fact that the regional administration regularly sends friendly warning letters aimed at promoting tax compliance within the context of the analyzed earmarking taxation. While a comprehensive analysis of friendly warning policies is not within the scope of our paper, we find evidence that the approach has been effective in encouraging a portion of the population to pay the tax. However, a significant portion of individuals did not perceive themselves at risk of enforcement and did not view the fine as a deterrent to complying with the law. The literature acknowledges the need for a more rigorous and resolute enforcement policy to overcome resistance to policy implementation. While some strategies, particularly nudging policies, and friendly warning communications, are being explored, finding a balance between political consent and public budget constraints may prove challenging for decentralized administrations due to their close proximity to citizens. In future research, it would be interesting to explore whether a nudge plus intervention (involving both a subtle prompt to pay the tax, the nudge, and an additional element of reflection, the plus) may prove more effective in encouraging tax compliance. Moreover, we plan to extend the present research if information over multiple years becomes available.

Our findings emphasize the importance for local (and central) governments to promote initiatives that cultivate a positive social environment and foster the perception of individual engagement in public decision-making, thereby facilitating the effectiveness of policy implementation. From this standpoint, although earmarking taxation and decentralization may not serve as sole remedies for ensuring compliance, they prove effective in encouraging it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B., G.G., P.L. and M.G.P.; methodology, L.B., G.G., P.L. and M.G.P.; software, G.G.; validation, L.B. and G.G.; formal analysis, G.G.; investigation, L.B., G.G., P.L. and M.G.P.; data curation, G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B., G.G., P.L. and M.G.P.; writing—review and editing, L.B., G.G., P.L. and M.G.P.; visualization, L.B., G.G., P.L. and M.G.P.; supervision, P.L.; project administration, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data required to reproduce the paper’s findings are not publicly available due to legal restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics of the dataset.

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics of the dataset.

| Macro Area | Ariable Name | Description of the Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness to evade car tax | 1 = if taxpayer evades taxes (on all vehicles); 0 = otherwise * | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 | |

| Vehicle variables | Car tax | Car tax due per individual taxpayer | 216.1 | 122.8 | 18.6 | 5658 |

| Average car tax per municipality | Average car tax per municipality | 216.2 | 7.19 | 193.9 | 257.9 | |

| Number of cars | No. of cars owned by taxpayer (individual) | 1.14 | 0.38 | 1 | 4 | |

| Number of cars (per capita) | Total no. of cars owned by taxpayers/total residents (per municipality) | 1.14 | 0.02 | 1.1 | 1.23 | |

| Present car value | Present car value (individual) ** | 40.58 | 56.3 | 0 | 1600 | |

| Average present car value per municipality | Average present car value per municipality | 40.56 | 3.91 | 21.62 | 51.95 | |

| Car age | Car age (individual) | 7.19 | 4.46 | 0 | 62 | |

| Average car age per municipality | Average car age per municipality | 7.19 | 0.46 | 5.99 | 9.5 | |

| Socio-economic and demographic variables | Taxpayer age | Taxpayer age (individual) | 52.47 | 15.01 | 0 | 99 |

| Average taxpayer age per municipality | Average taxpayer age per municipality | 52.45 | 1.31 | 48.92 | 58.53 | |

| Taxpayer income | Taxpayer income (individual) | 25,399 | 31,869 | −73,659 | 10,000,000 | |

| Foreigners | 1 = if taxpayer is not Italian (excluding Chinese); 0 = otherwise (base category: Italian) | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.21 | |

| % foreigners | % foreigners in the municipality on total residents | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.21 | |

| Chinese | 1 = if taxpayer is Chinese; 0 = otherwise | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.06 | |

| % Chinese | % chinese in the municipality on total residents | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.06 | |

| Marital status | 1 = if taxpayer lives as a couple or married; 0 = otherwise | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 | |

| Female | 1 = if taxpayer is female; 0 = otherwise | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0 | 1.00 | |

| % female in municipality | % of females in the municipality on total residents | 0.43 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.50 | |

| Employee | 1 = if taxpayer is an employee; 0 = otherwise | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Self-employed | 1 = if taxpayer is self-employed; 0 = otherwise | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Retired | 1 = if taxpayer is retired; 0 = otherwise | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Other source of income | 1 = if taxpayer has “other” sources of income; 0 = otherwise | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| “Not available” income | 1 = if taxpayer has no source of income; 0 = otherwise | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Economic environment variables | Number of firms per capita | Total number of firms/total residents | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.18 |

| % of firms in tertiary sector | % firms in tertiary sector on total firms | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.29 | |

| Average taxpayer income per municipality | Average taxpayers’ income per municipality | 36,358 | 5115 | 22,247 | 57,413 | |

| % employed | % employed taxpayers on total residents | 47.98 | 3.45 | 30.83 | 56.84 | |

| % self-employed | % unemployed on total residents | 7.89 | 1.84 | 3.06 | 14.93 | |

| % retired | % employed taxpayers on total residents | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.49 | |

| % self-employed | % self-employed taxpayers on total residents | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.22 | |

| % other source of income | % taxpayers with other source of income on total residents | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.17 | |

| % unemployed | % unemployed on total residents | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.15 | |

| Institutional variables | % volunteers | % of taxpayers active in the third sector and volunteer opportunities within the municipality | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.41 |

| Number of parties | Number of political parties that participated in the previous local elections | 6.57 | 3.54 | 1 | 15 | |

| % voters | % of voters in the previous local elections | 0.79 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.85 | |

| Distance from Florence | Distance from the capital Florence (in km) | 66.57 | 44.77 | 0 | 198.4 | |

| Tax burden per municipality | Tax burden pro capite per municipality | 1026.00 | 338.1 | 452.00 | 3574 | |

| Investment in transports | % of investments on transport per municipality | 45 | 50.99 | 0 | 1251 | |

| % Fixed public expenditure | Fixed public expenditure/total expenditures | 29.64 | 5.76 | 5.63 | 50.91 |

Notes: * the terms taxpayers and tax due refer to the earmarking taxation considered in this paper. ** Details provided in Equation (3).

Notes

| 1 | Brockmann et al. (2016) also mention a third mechanism that reinforces these two, which is the “warm glow of giving” (see Andreoni et al. 1998), which, given the direct influence over their use of money, makes individuals perceive themselves as benefactors of society and makes them feeling kind. |

| 2 | There is a difference between identified and prosecuted, since it is often more difficult at the local scale to recover amounts due to the economic, social and political cost of doing so. |

| 3 | Aci-Quattroruote report, Quattroruote, April 2014. |

| 4 | A specific tax surcharge is due for cars with an engine power exceeding 185 kW, depending on the car’s age. |

| 5 | Hereafter, the terms “car” and “vehicle” will be used interchangeably in the paper and refer to car ownership tax evasion. |

| 6 | We have considered in the dataset only those taxpayers on which relevant information was available and who either decided to pay or not to pay the full tax. As shown in Table 2, among those who did not pay, we were also able to further distinguish between late payers and tax evaders. |

| 7 | Once the payment due date has passed, and payment is not received by the local authority, the taxpayer receives a notice to comply with the obligation, the so-called ‘friendly warning’. |

| 8 | In this case, a tax return was not present in the administrative archive. |

| 9 | The ASY model takes its name from further development to the Allingham and Sandmo (1972) model suggested by Yitzhaki (1974). Hereafter, we will use the terms ‘ASY model’ or ‘traditional/conventional tax evasion model’ interchangeably. |

| 10 | In the first year after the due date, the penalty rate is very low and varies from 0.1% to a maximum of 0.375% (when payment is received after six months to one year of delay). If the taxpayer is classified as a tax evader, a fixed amount of 30% of the tax value, in addition to the tax itself, should be paid. |

| 11 | Unlike income taxation, ownership taxes do not allow people to evade part of the due tax. The taxpayer has only two options: evade the tax or pay the tax honestly. |

| 12 | Evidence on the use of friendly warning messages on tax compliance is controversial. Using social norms and public service messages, Hallsworth et al. (2017) found that reminder letters for overdue tax payments in the UK increased compliance. Similarly, according to De Neve et al. (2021), simplifying the communication of the tax administration and deterrence messages have a positive effect on tax compliance and are more efficient than invoking tax morale. However, other papers find no or insignificant effects of friendly warning messages on tax compliance. Galmarini et al. (2014, p. 22), for example, empirically find that receiving a tax notice (i.e., a friendly warning message) is “insufficient to correct the individual incentive to escape tax authorities”. They suggest complementing letters with other policies in order to reinforce the deterrence, such as giving public evidence of evaders and inhibiting loans and bank accounts. |

| 13 | In their study, Perez-Truglia and Troiano (2018) show for example that shaming tax delinquents and friendly warning reminders (varying the salience of financial penalties) increase compliance. However, receiving information on other’s non-compliance did not have any impact on tax compliance. |

| 14 | In this field experiment, after 30 days of receiving the reminder, all taxpayers who did not comply with their tax liability on property taxes received an additional penalty, which increased by 0.5 percentage points per month up to a maximum of 12%. |

| 15 | Many scholars suggest tax morale as being one of the main factors explaining individuals’ tax compliance (see (Torgler 2003) and (Luttmer and Singhal 2014) for a taxonomy). Others stress stigma and reputation costs as possible deterrents to tax evasion (see, e.g., Gordon 1989; and Blaufus et al. 2017). Spicer (1986) and Kirchler (2007) emphasized the relevance of ‘psychic costs’ to determine whether individuals are willing to engage in tax evasion and, more recently, Barile et al. (2022) empirically showed the impact of ‘moral hinterland’ variables on the willingness to engage in tax evasion and benefit fraud. |

| 16 | For each variable, we report the estimated coefficient, the associated standard errors, test statistic, p-value and 95% confidence interval. Different measures of R-squared are also reported, indicating the explicative power of the model. The effect of group effects is captured simultaneously with the effect of group-level predictors by the “municipality” variable using a multilevel random effects model. |

| 17 | The difference is computed by subtracting the expected probabilities for women and men in different age groups. |

| 18 | In this case, we do not consider the lowest quintile, as the small amount of tax due by taxpayers is more likely to lead them to pay late rather than evade the car tax. |

References

- Ahumada, Hildegart, Facundo Alvaredo, and Alfredo Canavese. 2007. The monetary method and the size of the shadow economy: A critical assessment. Review of Income and Wealth 53: 363–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberini, Anna, and Marco Horvath. 2021. All car taxes are not created equal: Evidence from Germany. Energy Economics 100: 105329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberini, Anna, and Marcus Bareit. 2019. The effect of registration taxes on new car sales and emissions: Evidence from Switzerland. Resource and Energy Economics 56: 96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Alberini, Anna, Marcus Bareit, Massimo Filippini, and Adan L. Martinez-Cruz. 2018. The impact of emissions-based taxes on the retirement of used and inefficient vehicles: The case of Switzerland. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 88: 234–58. [Google Scholar]

- Allam, Amir, Tantawy Moussa, Mona Abdelhady, and Ahmed Yamen. 2023. National culture and tax evasion: The role of the institutional environment quality. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 52: 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allingham, Michael G., and Agnar Sandmo. 1972. Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics 1: 323–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, James, and Benno Torgler. 2006. Culture differences and tax morale in the United States and in Europe. Journal of Economic Psychology 27: 224–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alstadsæter, Annette, Wojciech Kopczuk, and Kjetil Telle. 2018. Social networks and tax avoidance: Evidence from a well-defined Norwegian tax shelter. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 25191. International Tax and Public Finance 26: 1291–328. [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni, James, Brian Erard, and Jonathan Feinstein. 1998. Tax compliance. Journal of Economic Literature 36: 818–60. [Google Scholar]

- Angeli, Andrea, Patrizia Lattarulo, Eugenio Palmieri, and Maria Grazia Pazienza. 2023. Tax evasion and tax amnesties in regional taxation. Economia Politica 40: 343–69. [Google Scholar]

- Baldaccini, Damiano. 2023. Gettito e Compliance Nella Fiscalità Regionale: Il Pagamento del Bollo Auto in Toscana. Firenze: Federalismo in Toscana, IRPET, pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, Sanchayan, and Peter John. 2024. Nudge plus: Incorporating reflection into behavioral public policy. Behavioural Public Policy 8: 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, Lory, John Cullis, and Philip Jones. 2022. Ain’t That a Shame: False Tax Declarations and Fraudulent Benefit Claims. Warwick Working Paper, No. 1435. Coventry: Warwick Economics. Available online: https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/id/eprint/171019/ (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Blaufus, Kay, Jonathan Bob, Philipp E. Otto, and Nadja Wolf. 2017. The effect of tax privacy on tax compliance—An experimental investigation. European Accounting Review 26: 561–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghans, Lex, James J. Heckman, Bark H. Golsteyn, and Huub Meijers. 2009. Gender differences in risk aversion and ambiguity aversion. Journal of the European Economic Association 7: 649–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, Kristina M., Alexander W. Cappelen, Erik Ø Sørensen, and Bertil Tungodden. 2020. You’ve got mail: A randomized field experiment on tax evasion. Management Science 66: 2801–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmann, Hilke, Philipp Genschel, and Laura Seelkopf. 2016. Happy taxation: Increasing tax compliance through positive rewards? Journal of Public Policy 36: 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehn, Andreas, Christian Lessmann, and Gunther Markwardt. 2013. Decentralization and the shadow economy: Oates meets Allingham–Sandmo. Applied Economics 45: 2567–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, Alfonso, Rosaria Vega Pansini, and Stefano Pisani. 2018. Regional tax evasion and audit enforcement. Regional Studies 52: 362–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, Lucio, and Carlos Scartascini. 2015. Tax compliance and enforcement in the pampas: Evidence from a field experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 116: 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cerruti, Davide, Anna Alberini, and Joshua Linn. 2019. Charging Drivers by the Pound: How Does the UK Vehicle Tax System Affect CO2 Emissions? Environmental and Resource Economics 74: 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corte dei Conti. 2022. Giudizio di Parificazione sul Rendiconto della Regione Emilia Romagna. Roma: Corte dei Conti. [Google Scholar]

- Cranor, Taylor, Jacob Goldin, Tatiana Homonoff, and Lindsay Moore. 2020. Communicating tax penalties to delinquent taxpayers: Evidence from a field experiment. National Tax Journal 73: 331–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daude, Christian, Hamlet Gutierrez, and Angel Melguizo. 2013. What drives tax morale? A focus on emerging economies. Review of Public Economics 207: 9–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Neve, Jan Emmanuel, Clement Imbert, Johannes Spinnewijn, Teodora Tsankova, and Maarten Luts. 2021. How to improve tax compliance? Evidence from population-wide experiments in Belgium. Journal of Political Economy 129: 1425–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhami, Sanjit, and Ali Al-Nowaihi. 2007. Why do people pay taxes? Prospect theory versus expected utility theory. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 64: 171–92. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon, Amrita, and Carlo Perroni. 2001. Tax earmarking and grass-roots accountability. Economics Letters 72: 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulleck, Uwe, Jonas Fooken, Cameron Newton, Andrea Ristl, Markus Schaffner, and Benno Torgler. 2016. Tax compliance and psychic costs: Behavioral experimental evidence using a physiological marker. Journal of Public Economics 134: 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erard, Brian, and Jonathan S. Feinstein. 1994a. Honesty and evasion in the tax compliance game. The RAND Journal of Economics 25: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erard, Brian, and Jonathan S. Feinstein. 1994b. The Role of Moral Sentiments and Audit Perceptions in Tax Compliance. Public Finance 49: 70–89. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, Bruno S., and Alois Stutzer. 2005. Beyond outcomes: Measuring procedural utility. Oxford Economic Papers 57: 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmarini, Umberto, Simone Pellegrino, Massimiliano Piacenza, and Gilberto Turati. 2014. The runaway taxpayer. International Tax and Public Finance 21: 468–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangl, Katharina, Benno Torgler, Erich Kirchler, and Eva Hofmann. 2014. Effects of supervision on tax compliance: Evidence from a field experiment in Austria. Economics Letters 123: 378–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, James P. 1989. Individual morality and reputation costs as deterrents to tax evasion. European Economic Review 33: 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halla, Martin, and Friedrich G. Schneider. 2008. Taxes and Benefits: Two Distinct Options to Cheat on the State? IZA Discussion Papers No. 3536. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). Available online: http://ftp.iza.org/dp3536.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Halla, Martin, and Friedrich G. Schneider. 2014. Taxes and benefits: Two options to cheat on the state. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 76: 411–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallsworth, Michael, John A. List, Robert D. Metcalfe, and Ivo Vlaev. 2017. The behavioralist as tax collector: Using natural field experiments to enhance tax compliance. Journal of Public Economics 148: 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesen, Niels, and Dan T. Larsen. 2016. The power of financial transparency: An event study of country-by-country reporting standards. Economics Letters 145: 120–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaltar, Odkhuu. 2024. Tax evasion and governance quality: The moderating role of adopting open government. International Review of Administrative Sciences 90: 276–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchler, Erich. 2007. The Economic Psychology of Tax Behaviour. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lisi, Gaetano. 2014. The interaction between trust and power: Effects on tax compliance and macroeconomic implications. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 53: 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttmer, Erzo F. P., and Monica Singhal. 2014. Tax morale. Journal of Economic Perspectives 28: 149–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marien, Sophie, and Mark Hooghe. 2011. Does political trust matter? An empirical investigation into the relation between political trust and support for law compliance. European Journal of Political Research 50: 267–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolini, Gabriele, Laura Pagani, and Alessandro Santoro. 2022. The deterrence effect of real-world operational tax audits on self-employed taxpayers: Evidence from Italy. International Tax and Public Finance 29: 1014–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, Panayiotis. 2014. Tax Compliance Social Norms and Institutional Quality: An Evolutionary Theory of Public Good Provision No. 46. Brussels: Directorate General Taxation and Customs Union, European Commission. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/tax/taxpap/0046.html (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Orviska, Marta, and John Hudson. 2003. Tax evasion, civic duty and the law-abiding citizen. European Journal of Political Economy 19: 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Truglia, Ricardo. 2020. The effects of income transparency on well-being: Evidence from a natural experiment. American Economic Review 110: 1019–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Truglia, Ricardo, and Ugo Troiano. 2018. Shaming tax delinquents. Journal of Public Economics 167: 120–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukeliene, Violeta, and Austeja Kažemekaityte. 2016. Tax Behaviour: Assessment of Tax Compliance in European Union Countries. Ekonomika 95: 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Justicia, David, and Bernd Theilen. 2018. Education and tax morale. Journal of Economic Psychology 64: 18–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, Christoph A., and Benno Torgler. 2008. Direct democracy, decentralization and earmarked taxation: An institutional framework to foster tax compliance. Intertax 36: 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeidler, David. 1989. Subjective probability and expected utility without additivity. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 57: 571–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Friedrich. 2000. The Increase of the Size of the Shadow Economy of 18 OECD Countries: Some Preliminary Explanations. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/73324/1/wp0008.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Schneider, Friedrich, and Andreas Buehn. 2013. Estimating the Size of the Shadow Economy: Methods, Problems and Open Questions. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/97444/1/773137262.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Seely, Andrew. 2011. Hypothecated Taxation—Common Library Standard Note. UK Parliament. Available online: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN01480/SN01480.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Snow, Arthur, and Ronald S. Warren, Jr. 2005a. Ambiguity about audit probability, tax compliance, and taxpayer welfare. Economic Inquiry 43: 865–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, Arthur, and Ronald S. Warren, Jr. 2005b. Tax evasion under random audits with uncertain detection. Economics Letters 88: 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldani, Emilia, and Alice Ciccone. 2019. Stick or carrot? Asymmetric responses to vehicle registration taxes in Norway. Environmental and Resource Economics 80: 59–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, Michael. 1986. Civilization at a Discount: The problem of tax evasion. National Tax Journal 39: 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, Michael W., and Scott B. Lundstedt. 1976. Understanding tax evasion. Public Finance 31: 295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Torgler, Benno. 2002. Speaking to theorists and searching for facts: Tax morale and tax compliance in experiments. Journal of Economic Surveys 16: 657–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, Benno. 2003. Tax Morale: Theory and Empirical Analysis of Tax Compliance. Doctoral dissertation, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Torgler, Benno. 2007. Tax Compliance and Tax Morale: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Torgler, Benno, and Friedrich G. Schneider. 2007. The Impact of Tax Morale and Institutional Quality on the Shadow Economy. CESifo Working Paper, No. 1899. Munich: Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo). [Google Scholar]

- Torgler, Benno, and Neven T. Valev. 2010. Gender and public attitudes toward corruption and tax evasion. Contemporary Economic Policy 28: 554–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, Benno, Friedrich Schneider, and Cristoph A. Schaltegger. 2010. Local autonomy, tax morale, and the shadow economy. Public Choice 144: 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymula, Agnieszka, Lior A. Rosemberg Belmaker, Lital Ruderman, Paul W. Glimcher, and Ifat Levy. 2013. Like cognitive function, decision making across the life span shows profound age-related changes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110: 17143–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Till Olaf, Jonas Fooken, and Benedikt Herrmann. 2014. Behavioural Economics and Taxation (No. 41). Brussels: Directorate General Taxation and Customs Union, European Commission. Available online: https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-09/taxation_paper_41.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Yitzhaki, Shlomo. 1974. A note on income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics 3: 201–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).