Abstract

The objective of this study was to establish the relationship between certain institutional variables and the effectiveness of fiscal decentralisation in Latin America. To fulfil this objective, we took a sample of 15 Latin American countries for the years 1996 to 2020 to estimate the logarithm of GDP per capita based on the level of fiscal decentralisation, as well as its interaction with six institutional variables plus three control variables. The results show that institutional variables always modulate the effects of fiscal decentralisation, in most cases significantly and negatively, the exceptions being accountability with a positive result and government effectiveness with a non-significant result. It was concluded that in the presence of weak regulations, political conflicts, and corruption, fiscal decentralisation can worsen social or economic circumstances in Latin America.

1. Introduction

The normative thesis of fiscal federalism suggests that a decentralised form of government offers higher economic efficiency by providing a diversified set of goods and services that better match the preferences of geographically clustered consumers (Oates 1977). It is also undeniable that there are public goods that are limited to a specific jurisdiction, where their benefits, the expenditure they entail, and the revenue they require have an impact only in that jurisdiction. Thus, the benefit principle presents a territorial variable, where each jurisdiction is more efficient in terms of the spatial dimension of the services it provides.

On this basis, there is a whole economic tradition in favour of the implementation of decentralised models under the assumption of their greater capacity to respond to citizens’ needs more efficiently, which, in the long run, may result in higher economic growth and better social outcomes (Pinilla-Rodríguez et al. 2014, 2016). However, not all the literature share this idea. There is a significant body of work that gives a negative account of the relationship between decentralisation and efficiency, stating that in certain circumstances (economies of scale, competency confusion, corruption, soft budget constraints, and others), centralised provision may be more efficient (Rodríguez-Pose and Bwire 2005).

In a representative study, Prud’homme (1995) was among the first to point out that the benefits of decentralisation are not as evident as classical theory would have it, and that its implementation has serious drawbacks that must be considered. The problem should not exclusively revolve around the opposites of centralise or decentralise. Consideration should be given to the concrete objectives to be achieved, which sectors and for which regions or jurisdictional levels. Bahl (1999) argued that the literature has focused too much on evaluating decentralising experiences in contrast to practice versus theory and has given little importance to implementation strategies.

However, only a comprehensive understanding of the process, including its institutional framework, allows for the evaluation of a decentralisation strategy. As Rodden (2003) put it, the effects of decentralisation are conditioned by the governance framework in which the process takes place, so that the potential benefits of decentralisation are not based on decentralisation per se but rather on the institutional features that accompany it. It is necessary to integrate political and economic institutions to understand how and in what circumstances decentralisation can be beneficial, which depends significantly on circumstances such as authority structures or the arrangement of intergovernmental relations (Hankla 2009).

Fiscal decentralisation is not a “magic recipe”. It requires the presence of an adequate institutional framework, especially at a local level. It has been evident for several years now that a wide range of variables affects decentralisation efforts. More attention needs to be paid to institutions in the design of decentralisation processes, with a greater focus on accountability, governance, and administrative capacity (Litvack et al. 1998). A crucial factor separating successful and unsuccessful examples of decentralisation is the quality of institutional design, especially at a sub-national level (Hankla 2009).

From an empirical perspective, the evidence also points to demystifying decentralisation and shows that its potential advantages are possible only under certain conditions. Decentralisation by itself is not a possibility (Sharma 2006). It depends on the existing governance creating the right incentive environment. In this respect, Enikolopov and Zhuravskaya (2003) argued that the lack of empirical findings on the effects of decentralisation is because numerous studies do not consider the importance of political institutions. As Voigt and Blume (2012) pointed out, attempts to estimate the economic effects of decentralisation cannot ignore potentially important institutional details. More needs to be known about the transmission mechanisms that decentralisation promotes.

This is especially true for developing countries, where institutional characteristics constitute a challenge to the classical normative theory and have implied the advance of new theoretical proposals or controversial models and empirical results. In this respect, it is important to point out how, without further questioning, many Latin American countries modified their fiscal structures on the conceptual categories and instruments of fiscal federalism, which were developed for industrialised countries with a long federal tradition, ignoring that many of the expected stimuli and incentives would not be realised under certain prevailing conditions (a centralist tradition, limited capacity for displacement, reduced levels of public goods, low tax burden, poor democratic performance, weak local administrative structures, etc.) (González 1994).

As Litvack et al. (1998) point out, much of the literature on decentralisation (normative and empirical) focuses on developed countries and assumes the existence of institutions that do not exist or are very weak in developing countries. Governments in many developing countries are often unresponsive to their citizens, and decision-making is rarely transparent and predictable. Opportunities for participation, punishment, or exit are limited due to weak institutions. Democratic systems are often fragile, making the electoral system a highly problematic method of achieving accountability. Strong, broad-based local participation can overcome weak, formal electoral systems, but local elites make this difficult in many places. Mobility is often constrained by a lack of information, infrastructure, and legal frameworks, resulting in weak markets for land, labour, and capital. There is no doubt that the special characteristics of developing countries represent a challenge for decentralisation, and the theory must be modified to take them into account to realise the advantages of decentralised government (Ahmad and Brosio 2006).

In the presence of weak institutions and political conflict, decentralisation might even worsen social circumstances. The benefits or detriments of decentralisation have conflicting formulations and evidence, depending on the characteristics of the process and the governance framework in which it takes place. In the end, the likelihood of being more responsive to local preferences depends on various incentives and how policy decisions are made. These incentives depend on the institutional structures that facilitate or hinder actors’ behaviour. In this regard, it is increasingly evident that explaining decentralisation processes requires the inclusion of governance. Rules and structures matter (Stein 1999). The question is as follows: what are the rules and structures that “matter”?

Initially, a large body of literature highlighted the importance of democratic intensity in decentralised public action (Tanzi 1995). Most of the benefits derived from decentralisation are in some way related to increased accountability and transparency in local governments (Hankla 2009; Hankla and Downs 2010). Democratic institutions are required to ensure that the community exercises control over government affairs at a local level. Giving powers to local governments that are not accountable to their populations may not improve outcomes but rather worsen them. If accountability is incomplete, decentralisation creates powerful incentives for local elites to capture the local political process and divert public resources to satisfy their own aspirations, rather than those of the wider community (Eckardt 2008).

In this respect, it is often assumed that the geographical proximity between those who govern and those who are governed, which increases with decentralisation, favours citizen participation and accountability. In the long run, this makes it more likely that sub-national authorities will provide citizens with the level of quality and governance they desire. But this will only be possible if each jurisdiction takes responsibility for its competencies, is explicit about its institutional relations with other jurisdictions, and is democratically elected in a competitive regime (Roubini and Sachs 1989; Grilli et al. 1991; Bird and Vaillancourt 1998; Manor 1999; Franzese 2002).

Transparent budgetary processes and public procurement procedures, or the distribution of fiscal powers that link tax levels to the quality of locally provided services, are also valued positively (Litvack et al. 1998). In this respect, Huther and Shah (1998) empirically confirmed that citizen participation promotes public sector accountability, which in turn creates the enabling environment for optimal decentralisation.

However, it is necessary to accept, especially in the case of Latin America, that many sub-national political processes are characterised by a low democratic quality, where representative methods of decision-making are weak or are co-opted by local elites who do not promote the public interest and hijack resources in the absence of transparency and accountability (Narayan 1998). Closeness also brings personalism to relationships, and when this occurs, the public interest is often sacrificed in favour of individuals or groups (Tanzi 1995). Perhaps for this reason, the literature assessing the relationship between decentralisation and corruption stresses the need to include in the analysis factors such as inter-jurisdictional mobility and competition, the effective possibility of monitoring and accountability, the degree of dispersion of decision-making powers, and bureaucratic competence and quality (Shleifer and Vishny 1993; Jin et al. 1999).

A strong rule of law would be a further positive institutional factor. The presence of a certain framework of compliance with and trust in social rules and respect for rights can also be a reason for effective decentralisation. The precise allocation of the revenue and expenditure rights of jurisdictions, a rational transfer system, and effective decentralisation and restraint mechanisms would enhance the benefit of the decentralisation process.

The quality of public administration can also be a determinant of the positive impact of a fiscal decentralisation process. If the civil service in general, but especially the local civil service, is of high quality and is exercised in a technical and independent manner with modern planning and control systems, fiscal decentralisation can achieve better results. The fiscal responsiveness of sub-national governments is related to their administrative competence (Manor 1999). Building strong administrative structures is vital for effective decentralisation (Hankla 2009). Of course, if the quality of local bureaucracies is poor and if the public interest is not the guiding principle for local officials, independence and experimentation by local jurisdictions may not achieve the desired results (Tanzi 1995).

In this respect, it must be highlighted how in Latin America, sub-national governments have received new competencies without renewing their administrative structures. This often generates levels of inefficiency in day-to-day operations (Cabrero Mendoza et al. 1997), aggravated by the shortage of trained civil servants (monopolised by central governments that offer better working conditions), something that impedes decentralisation efforts (Murphy et al. 1991; Prud’homme 1995). In general terms, Latin American governments have advanced fiscal decentralisation without considering the conditions in which their sub-national governments find themselves and, even worse, without implementing any consistent and systematic policy to strengthen their administrative and managerial capacities (Campbell et al. 1991). As Nickson (2023) states, the transfer of new powers and financial resources to local governments does not guarantee an increase in the efficiency and effectiveness of local service delivery if administrative practices are not improved. The first pending challenge would be the constitution of true municipal career systems that break with the current caudillismo and the high bureaucratic turnover.

Likewise, the quality of regulation, especially of fiscal institutions, can make the difference between successful and unsuccessful decentralisation. It is presumed that the government has formulated and implemented sound, effective, coherent, and simple fiscal policies and regulations that are consistent with other regulations and are implemented in an equitable, transparent and proportional manner as part of the decentralisation process. However, Latin American countries are characterised by weak regulations that encourage fiscal indiscipline. Countries in the region have not paid sufficient attention to strengthening institutional capacity in the budgetary framework (Shah 1998; Stein et al. 1998; Alesina et al. 1999).

In addition to the institutional factors outlined above, in empirical terms, a variety of factors have been identified as determinants of an effective decentralisation process: optimal allocation of public expenditures across regions, appropriate coordination channels, instruments such as training and adequate financial planning (Robalino et al. 2001); political and bureaucratic leadership of the central sector (Robalino et al. 2001; Heywood and Choi 2010); income level, democratic and institutional quality, ethnic tensions and ethno-linguistic fragmentation (Khaleghian 2003; Nana 2009); informal governance and political culture (Atkinson and Haran 2004); the effective level of political decentralisation (James et al. 2004); the degree of local voters’ political education, social homogeneity, and coordination of preferences (Ahmad et al. 2006); the proper design of intergovernmental transfers and local fiscal autonomy (Uchimura and Jütting 2009); and the decentralisation of revenue sources (Nana 2009; Akpan 2011; Jiménez 2011).

Kyriacou et al. (2015) found that decentralisation promotes regional convergence in environments of high government quality and leads to wider regional disparities in countries with poor governance. Hanif et al. (2020) showed that the impact of fiscal decentralisation on economic growth is attenuated in the presence of corruption, weak institutions, and/or political instability. Arif and Ahmad (2020) presented evidence regarding the positive effect of fiscal decentralisation on economic growth, provided it is complemented by a strong institutional structure in terms of rule of law (RLaw), low corruption, high bureaucratic quality, and democratic accountability.

In short, decentralisation is a process whose evaluation must be conducted by defining the governance context in which it is being implemented. Institutional details are important. Empirical results can be quite different if aspects of the governance structure are included (Voigt and Blume 2012). It is hypothesised that the process will show better efficiency results if constitutional and legal frameworks are clearly defined and enforced; if political and administrative processes are transparent and oriented towards the public interest; if participation, freedom of expression, and accountability are enhanced; if a framework of political stability is present; and if the government is administratively efficient, accountable, and independent. The success of the process hinges on institutional components such as inter-jurisdictional competence or coordination, effective monitoring and accountability, dispersed decision-making powers, and bureaucratic capacity and quality.

There is a need to focus on the relationship between specific political institutions and the efficient provision of local public goods in fiscally decentralised systems. Few scholars have examined how government institutions support the social welfare gains expected from decentralising processes. An attempt should be made to construct a more robust “decentralisation theorem” (Ponce-Rodríguez et al. 2020).

For this purpose, it is necessary to analyse decentralisation as a specific process, which requires contextual and extensive information for building knowledge in this field. By identifying the institutions that are important for decentralisation and that may be fragile in developing countries, it is also possible to identify ways to compensate for weak institutions in the short term and build key elements of important institutions in the long term.

In this way, the goal is to account for the growing decentralising experience by identifying governance variables beneficial to the decentralising process. To be sure, much of the discussion on fiscal federalism has revolved around a curious combination of strong preconceived beliefs and limited empirical evidence. However, there are now well-established processes and precise effects to assess. It is no longer a debate confined to institutional description or ideology but can be based on results and new theoretical horizons and available data, which recognise that the best design will vary according to circumstances and institutions and that this complexity has sometimes been overlooked.

This is especially true for Latin America in the period under study (1996–2020), as it presents some circumstances that make it productive in validating these hypotheses. Decentralisation in Latin America has been one of the most significant economic and political developments in the last three decades. It has undoubtedly redefined public policies, especially distributive ones. For years now, many components of social policy have been left to sub-national governments in the belief that they will achieve better social welfare outcomes.

Decentralisation in Latin America was first a political and structural reform process driven by the idea that a system of local governments was economically and politically more profitable. This idea, adopted without questioning the institutional framework within which it was to develop, turned decentralisation into an end rather than the means that it really is, under the political motivation of transforming a centralised and authoritarian state into a decentralised and democratic one (Burki et al. 1999; Mascareño 2009). The autonomy of local jurisdictions was promoted with the guarantee of transferring large fiscal resources from the central government, where the transfers became the main instrument of decentralisation.

In the end, the mismatch between local spending and tax effort widened the gap between the institutions and citizens, contrary to the promise of decentralisation. In states such as Oaxaca and Chiapas (Mexico); in municipalities in the northeast of Brazil, such as Alagoas and Maranhão; in provinces such as Formosa and Santiago del Estero (Argentina); or in regions such as Huancavelica and Apurímac (Peru), low-tax-collection Local governments have contributed to dependence on transfers from the central government, which has created the perception that public services are financed and controlled by an external agent, reducing responsibility and accountability at the local level. The dependence on national funds has led citizens to see local services as external services and managed by a distant level of government (Cabrero Mendoza 2004; Hernandez-Trillo and Jarillo-Rabling 2008; Rezende and Afonso 2006; Shah 2004; Porto and Sanguinetti 2001; Ahmad and García-Escribano 2006).

Achieving efficiency in the management of resources by subjecting public services to more direct public scrutiny is not possible if they do not see them as a collective patrimony. Citizen participation in public management did not occur in the terms and at the levels announced because real incentives to encourage participation were lacking. Sub-national governments were fiscally strengthened, but political practices were not transformed. As the drawbacks became evident, central governments adopted a more cautious attitude towards reforms, imposing stricter regulatory frameworks for intergovernmental finances and monitoring systems and evaluating the fiscal performance of sub-national entities. A “comprehensive strategy” that considered public sector governance was required.

In this framework, the objective of this research was to verify the impact that decentralisation processes have had in Latin America and identify which governance determinants modulate their effectiveness and how they do so. In other words, the aim was to estimate the level of economic efficiency of fiscal decentralisation for a set of Latin American countries and to establish the interaction that certain institutional factors have in this respect. We aimed to find which governance variables correct the social efficiency of fiscal decentralisation processes and how intensely they do so. In concrete terms for the case of Latin America, is the quality of accountability or the rule of law the institutional characteristic that has promoted effective fiscal decentralisation? Or are political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, and corruption control the key institutional variables that explain successful fiscal decentralisation processes? Or, on the contrary, some of these institutional variables cause fiscal decentralisation to present negative results.

2. Materials and Methods

To establish the modulating role of certain institutional variables on the possible positive impact of fiscal decentralisation in Latin America, a panel-data-modelling approach was used for a sample of 15 Latin American countries for the years 1996 and 2020. Economic growth was taken as the dependent outcome variable. That is, this variable was adopted as a proxy for the level of economic efficiency that fiscal decentralisation has had in Latin America. The proposal was conducted through a static analysis, in which fixed effects or random effects estimations were developed according to the origin of the unobserved heterogeneity.

Under this modelling system, we intended to estimate a socio-economic outcome variable (logarithm of GDP per capita) by considering the decentralisation variable (sub-national public expenditure as a percentage of general government public expenditure), as well as its interaction with six governance variables. Also included were three control variables, namely social expenditure, gross capital formation, and the degree of openness of the economy, as indicated in Equation (1):

where i refers to countries and t to years; α is a constant; GDPpC is economic output (economic growth); DF is a fiscal decentralisation variable; GI is an institutional governance variable; X is a vector of control variables; and ε is the error term.

The GDPpC variable is the logarithm of GDP per capita in US dollars at constant 2018 prices. The data were taken from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WGI) database. As Baskaran et al. (2016) point out, the theoretical literature on fiscal federalism has identified several channels through which decentralisation affects economic growth. Efficiency is the decentralised provision of public services or the increasing capacity of the political system to innovate and conduct reforms. Other authors argue that decentralisation increases corruption or inefficiency and thus decreases economic growth.

Despite the theoretical ambiguity, and the fact that the results may depend on the characteristics of the empirical models and the sample used, the literature generally finds a positive and significant relationship between levels of decentralisation and the volume of output per capita (Xie et al. 1999; Lin and Liu 2000; Akai and Sakata 2002; Feld et al. 2004; Iimi 2005; Qiao et al. 2008; Gemmell et al. 2013; Blöchliger and Égert 2013). Particularly for Latin America, Pinilla-Rodríguez et al. (2016) provided evidence of the positive, long-term impact of fiscal decentralisation on economic growth. Other authors such as Bojanic (2018) established for the case of 10 Latin American countries, and without the inclusion of institutional variables, that fiscal decentralisation on the income side exerts a negative influence on growth, but the decentralisation indicator of the spending seems to show a positive influence.

With respect to fiscal decentralisation, it is important to point out that its dimensions are multiple since the instruments on which it plays out are the volumes of fiscal resources spent or received by sub-national governments. The concrete autonomy these governments have for managing resources can be diverse. The practical inconveniences derived from the availability of information to construct a valid measure of physical decentralisation in Latin America are also well known (Martner 2005).

In our case, the variable sub-national public expenditure as a percentage of total general government expenditure (FDExp) was adopted. This measure captures regional and local governments’ share of expenditures as a proportion of total general government spending. The measure excludes the portion of spending that is transferred to other levels of government, foreign governments, and international organisations. Measuring only subnational spending may not fully capture fiscal autonomy and responsibility, especially if subnational governments depend largely on transfers from the central government. On the other hand, subnational governments may have different responsibilities in terms of services and functions, which are not adequately reflected through expenditure alone, and in some cases, central governments may impose financial mandates, distorting the real picture of decentralisation. However, despite its limitations, this variable is considered to represent, in a comprehensible way, how fiscal decentralisation has evolved in Latin America in the period under study; although, it is noted that the results are closely linked to the decentralisation variable that has been chosen. The data were taken from the fiscal decentralisation database of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Regarding the exogenous variables, Table 1 details those related to the quality of institutions or governance, which were extracted from the WGI database, which reports aggregate and individual governance indicators for more than 200 countries.

Table 1.

Description of governance variables.

All governance indicator scores have been re-scaled to values of 1 (lowest perception of a governance dimension) and 6 (highest perception).

The control variables are central government social public expenditure (GPS, measured as % of GDP), gross fixed capital formation (GFCF, measured as % of GDP) and the openness rate of the economy (OPEN), represented by the sum of imports and exports as a percentage of GDP. The choice of control variables was guided by the need to consider factors that may affect the relationship between fiscal decentralisation, institutional quality, and economic growth, and whose omission could bias the estimated relationships between these variables. The values for public social expenditure were taken from ECLAC’s Cepalstat database, while the values for OPEN and GFCF were taken from the World Bank’s national accounts database.

To analyse these data, which merge temporal elements with cross-subject comparisons, it was necessary to apply panel data analysis techniques. This approach recognises the need to address the inherent heterogeneity in the data, both across subjects (such as countries) and over time. This uncaptured heterogeneity is reflected in the error term, which is composed of the standard estimation error, random noise, and the error arising from unexplained heterogeneity, which remains constant over time.

When estimating, this heterogeneity can be assumed to be related to the explanatory variables, indicating differences between subjects, or it can be considered as random. In the first scenario, fixed effects methods are employed, while in the second, random effects are chosen. If a correlation is confirmed, the estimation may be biased. To mitigate this, the fixed effects approach adjusts variables and errors to their means, eliminating the impact of unobserved heterogeneity.

Random effects estimation, on the other hand, assumes that there is no correlation between the explanatory variables and the unobserved error and adjusts for differences weighted by a factor related to error variance and heterogeneity. The choice between fixed and random effects is guided by the Hausman test, which determines the appropriateness of random versus fixed effects. As regards selecting fixed effects, it is necessary to validate the absence of heteroskedasticity and its corresponding adjustment using generalised least squares (GLS), which allows an efficient estimation of coefficients considering both autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity.

An initial model was estimated, in which the economic growth variable was a function of the control variables and the decentralisation variable. Similarly, and for each institutional variable, two models were estimated: (a) an unrestricted model in which only the control variables, decentralisation variable, and institutional variable were introduced as determinants and (b) a restricted model in which the interaction between the decentralisation variable and the institutional variable was also introduced.

The results must be interpreted with due caution, as in most of the literature. Firstly, the decentralisation variable is limited, in that it does not capture all of the multiple dimensions of a decentralisation process. Secondly, the GDP per capita variable may not fully reflect the underlying level of a society’s social welfare, others being more informative and conclusive. Thirdly, environmental variables have been adopted as determinants of the realisation of certain social outcomes, as well as of the efficiency of decentralising processes. Yet, it is possible that other variables, for which we do not have a complete or homogeneous series, may be even more relevant.

3. Results

Economic Growth, Decentralisation and Governance

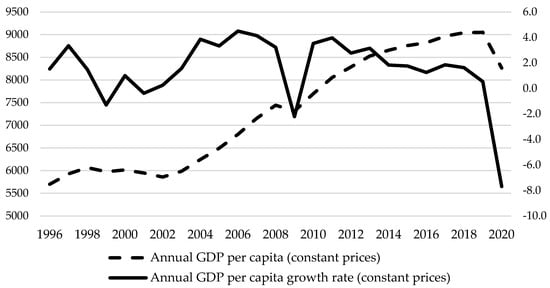

As can be seen in Figure 1, from 1996 to 2020, Latin America experienced various stages of economic growth. In the late 1990s, the region suffered economic turbulence due to the Asian financial crisis that affected several Latin American countries, especially those with more vulnerable economies dependent on external capital flows.

Figure 1.

15 Latin American countries: GDP per capita and its average rate of change (1996–2020). Source: created by the authors based on ECLAC (2024).

There were external imbalances, falling exports, and capital flight in a scenario of macroeconomic imbalances. However, some strengths moderated these negative effects (1998–2003). Starting in the first decade of the 21st century, many Latin American countries benefited from rising commodity prices, such as oil, metals, and agricultural products. There was strong recovery driven by an improvement in the terms of trade. The region enjoyed a higher utilisation rate of productive factors that were underutilised in the previous recessionary period. This boosted economic growth in countries such as Brazil, Chile, and Peru, which are major commodity exporters (2004–2008).

In 2008, the global financial crisis had a significant impact on Latin America, although the region was not as severely affected as other parts of the world due to the possibility of activating contracyclical fiscal policies and controlling exchange rate depreciations. However, there was an economic slowdown in several countries and a fall in foreign investment flows and international trade. Finally, the fall in commodity prices in 2014–2015 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 affected the GDP of all countries across the world, but the swings in Latin American economies were significantly more pronounced. Importantly, economic performance has been heterogeneous across the region. Some countries, e.g., Chile, Peru, and Colombia, achieved strong economic growth and macroeconomic stability, while others, such as Venezuela and Argentina, faced severe economic crises and recessions.

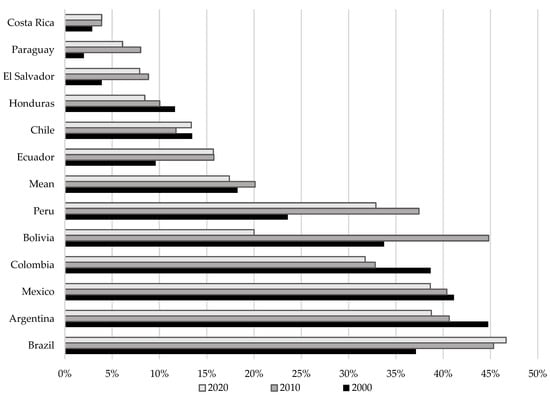

As can be seen in Figure 2, regarding the fiscal decentralisation variable, sub-national expenditure (as a percentage of general government expenditure) shows an average decrease of 0.83%. This slight decrease or stabilisation in decentralisation levels responds to the fact that after a period of increasing sub-national expenditure, a set of reforms at the end of the 1990s put an end to quantitative expansion through transfers, with the aim of imposing new priorities (sound local finances, moderate indebtedness, local tax effort, the promotion of market mechanisms, and a justification of the number of administrative levels) (Restrepo 2004).

Figure 2.

12 Latin American countries: sub-national public expenditure (% of general government public expenditure) (2000, 2010, and 2020). Source: created by the authors based on the IMF’s fiscal decentralisation database.

In the end, the countries with the highest ratios (as an average for the period) are Argentina (42%), Mexico (41%), and Brazil (39%), followed by Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru, with percentages of 30 to 34%. Lower ratios were observed for Ecuador, Guatemala, Chile, and Honduras, with percentages of 15 to 10 percent. Finally, El Salvador, Paraguay, Costa Rica, and Panama had ratios of less than 10%.

With respect to the governance variables, with values of 1 (lowest perception) and 6 (highest perception), the values range between 3.0 and 3.8, which indicates that the level of governance in Latin America is low, especially for rule of law. In contrast, accountability had the highest perception. In temporal terms, there is no evidence of any progress or regression in the governance dimensions in the period studied, with persistent challenges in areas such as democracy, corruption, institutional fragility, and state management capacities.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of all variables. The participation and accountability variable stands out for its highest average value among all institutional variables. It is also true that all these variables present low average values and little progress in the period under study, which denotes very little institutional progress in Latin America in the period under study.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables: Logarithm of GDP per capita, control variables, and governance variables (1996–2020).

Table 3 presents the results of the regression models specified in Equation 1 for the logarithm of GDP per capita as a function of sub-national public expenditure (% of general government public expenditure), the institutional variables (accountability, rule of law, and quality of regulation), the institutional variables in interaction with the sub-national expenditure variable, plus the control variables. The goodness of fit of the models is appreciable if we consider the significance of the variables and of the estimates in general.

Table 3.

Logarithm of GDP per capita, fiscal decentralisation, and governance variables (accountability, rule of law, and regulatory quality) in interaction with the decentralisation variable. Random and fixed effects estimation were corrected for heteroskedasticity.

Model 1 includes only the control variables and the decentralisation variable. All control variables appear to be significant and with the expected sign, except for OPEN. This would indicate that, without considering the governance framework, public social spending, GFCF, and the level of sub-national spending may be explanatory variables for economic growth in Latin America in the period under study.

Models 2 and 3 include the institutional variable of citizen participation and accountability (PA) and its interaction with the decentralisation variable. The results suggest that fiscal decentralisation and especially the institutional variable of accountability promote economic growth (Model 2). The inclusion of the accountability variable maintains the coefficients and significance of the fiscal decentralisation variable, suggesting that there is no omitted variable bias with respect to the accountability variable.

Nonetheless, the role of accountability becomes clear when it interacts with fiscal decentralisation (Model 3). It had been argued that decentralisation could achieve better efficiency gains in the presence of better democratic quality. This expectation is supported by the fact that the interaction term between fiscal decentralisation and the participation and accountability variable is positive and statistically significant. Even the value of the coefficient could indicate that, in the case of Latin America, institutional conditions of accountability have promoted a greater positive impact of fiscal decentralisation.

These results provide evidence of how certain improvements in democratic conditions in Latin America in the period under study have been able to reinforce the positive effects of a certain level of fiscal decentralisation. It is noteworthy that of all the governance conditions analysed, accountability had the highest perception in the period under study, which would indicate the presence of certain conditions that promote the efficiency sought in fiscal decentralisation processes: public control over local public affairs, jurisdictions responsible for their competencies, and competitive local electoral processes. Accountability, or increased information about local government activities, has created incentives for elected officials and civil servants to reduce opportunistic behaviour and improve their performance, which has promoted better local services.

Models 4 and 5 include the institutional variable RLaw and its interaction with the decentralisation variable. The results again suggest that fiscal decentralisation and rule of law promote economic growth (Model 4). However, the role of the quality of RLaw modulates the effects of fiscal decentralisation differently from that of accountability. The negative and significant interaction term between decentralisation and RLaw (Model 5) indicates that, for Latin America, low trust and compliance with rules have limited the efficiency gains expected from decentralisation in relation to economic growth.

It may be that for Latin America, revenue and expenditure entitlements have not been correctly allocated to local authorities. Or it might be that the transfer systems, the main instrument of decentralisation in Latin America, are not very transparent, have poorly defined allocation criteria, or are not adapted to local conditions, which makes the general transfer system an unreliable set of rules or with a high component of discretion.

Models 6 and 7 include the institutional variable of regulatory quality (RQ) and its interaction with the decentralisation variable. The results again suggest that greater fiscal decentralisation and RQ promote economic growth (Model 6). However, the negative and significant interaction term between decentralisation and RQ (Model 7) indicates that, for Latin America, low government capacity to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations has made decentralisation processes harm economic growth.

This is an expected result that is in line with the findings on the interaction with the quality of the RLaw. It is evident that the regulatory quality of sub-national fiscal institutions has been low, which has hampered the potential efficiency gains of decentralisation processes. Such a regulation plays a key role in promoting fiscal discipline and stability, and hence, economic growth. Nevertheless, the processes may not have been adequately designed in consideration of the circumstances of each country or jurisdiction or may not adequately balance fiscal responsibilities between central and sub-national governments.

As seen in Table 4, models 8 and 9 include the institutional variable of political stability and its interaction with the decentralisation variable. The coefficients of Model 8 and their significance indicate that fiscal decentralisation and the perception of political stability promote economic growth, especially on the part of the institutional variable. However, the negative and significant interaction term between decentralisation and political stability (Model 9) indicates that political instability in Latin America has caused decentralisation processes to harm economic growth. Weak national or sub-national political institutions or the presence of politically motivated violence mean that further fiscal decentralisation has limited rather than promoted economic growth.

Table 4.

Logarithm of GDP per capita, fiscal decentralisation, and governance variables in interaction with the decentralisation variable. Random and fixed effects estimation were corrected for heteroskedasticity.

Models 10 and 11 include the institutional variable of government effectiveness (GovEffec)—i.e., the quality of public services and of public policy formulation and implementation—and its interaction with the decentralisation variable. The coefficients of Model 10 and their significance indicate that government effectiveness does not explain economic growth, while fiscal decentralisation retains its explanatory power. However, the non-significant term of the interaction between decentralisation and government effectiveness (Model 11) indicates that the low quality of public services in Latin America makes decentralisation processes less effective in terms of the overall efficiency of the economic system. This confirms what Cabrero Mendoza et al. (1997) established, that the administrative competencies of sub-national governments in Latin America have not been completely updated, which has nullified the expected efficiency effects of decentralisation.

Finally, Models 12 and 13 include the institutional variable of corruption perception (Corr) and its interaction with the decentralisation variable. The results suggest that corruption does not affect economic growth (Model 12). The inclusion of the corruption variable maintains the coefficients and significance of the fiscal decentralisation variable, suggesting that there is no omitted variable bias with respect to the corruption variable. However, the effect of controlling corruption becomes evident when interacting with fiscal decentralisation (Model 13). The interaction term between these variables is negative and statistically significant. This indicates that, given the level of corruption control in Latin America, decentralisation processes have hindered rather than boosted economic growth.

An overview of the estimated models shows that in all of them, the decentralisation variable appears positive and with a positive sign. Although it is accepted that the relationship between fiscal decentralisation and economic growth is complex and varies according to the context, in Latin America, our evidence shows that fiscal decentralisation can be a robust explanatory variable of economic growth in the long run. Greater autonomy may have promoted efficiency, the promotion of collective goods, and the utilisation of productive resources.

Nonetheless, what is also evident is that this relationship is negatively affected by the governance framework in which decentralisation takes place. Most of the governance variables in interaction with decentralisation appear significant and with a negative sign, except for accountability (which appears with a positive sign) and government effectiveness (which appears to be non-significant). This provides empirical evidence on how the governance framework, in most of its dimensions, modulates the possible effects of decentralisation in the region under analysis. If we stick to the value of the coefficients, we can identify corruption as the most determinant institutional factor in reducing the positive impact that decentralisation can have. This is followed by regulatory quality and rule of law.

4. Conclusions

As has been shown, there are many important theoretical and common-sense reasons to expect a productive relationship between decentralisation and the achievement of various social and economic outcomes. Nevertheless, these positive outcomes are linked to an appropriate institutional design and environment. Emphasising the institutional aspects of intergovernmental fiscal relations is, of course, not new. However, there has been a scarcity of empirical exploration into the role of the institutional environment in the success of decentralisation processes and specifically which institutional determinants matter and how they matter.

To help bridge this gap, the links between fiscal decentralisation (local spending as a % of general government spending) and economic growth have been explored for the Latin American case by considering six institutional factors that may determine the effectiveness and direction of this relationship. The structural variables included central government social public expenditure (% of GDP), gross fixed capital formation (% of GDP), and the openness of the economy, represented by the sum of imports and exports as a percentage of GDP. Several models integrating all of these variables were estimated using data from 15 developing countries for the years 1996 to 2020 by means of fixed or variable effects general least squares. Broadly speaking, the fit of the models is sufficient.

We independently estimated that fiscal decentralisation, accountability, rule of law, regulatory quality, and political stability are variables that positively and significantly explain economic growth in Latin America in the period under study. This is especially true for the institutional variables if we consider the value of their coefficients.

Nevertheless, when verifying their interaction, that is, when evaluating the effect of fiscal decentralisation on economic growth by considering the institutional variables at the same time, we obtained, in all cases, significant coefficients with a negative sign. In this way, it was firstly empirically proven that the institutional framework, regardless of the dimension considered, is always relevant in establishing the effects of a decentralisation process. Importantly, our evidence showed that any evaluation of decentralisation processes must consider the governance framework in which they have been developed. It does not seem possible to consider this without considering the overall public action structure in which it has evolved. The theoretical underpinning and the empirical evidence presented do not cast any doubt upon this.

Concerning the question of which rules matter, it is worth noting that the effect of interaction is not the same for all institutional conditionalities. Specifically, for Latin America in the period under study, fiscal decentralisation has a greater positive impact if we consider the framework of democratic quality and accountability, which was the governance dimension that had the highest level of perception. In contrast, low levels of compliance with the rule of law and regulatory quality, political instability, or corruption not only hinder the positive results of fiscal decentralisation but also create negative results. In other words, considering the present level of these institutional factors, decentralisation has reduced rather than promoted economic growth.

Finally, it must be stressed that the level of government effectiveness, i.e., the quality of the bureaucracy and public services, eliminates the positive or negative effect that fiscal decentralisation may have on economic growth. This may confirm for the Latin American case what Murphy et al. (1991) or Prud’homme (1995) stated about how central bureaucracies attract more skilled people, while sub-national governments maintain a low-skilled workforce. If individuals with optimal qualifications are in short supply, it is difficult for sub-national governments to recruit and retain staff who are as qualified as central government personnel. Local talent shortages will undoubtedly hamper fiscal decentralisation efforts. The effectiveness of decentralisation processes is also hampered by cultural factors and a lack of adequate public expenditure management structures.

In this way and in terms of economic policy, the results and their possible interpretations point out the need for Latin America to make progress in improving local democracy and promote the strengthening of local capacities, developing municipal career systems, increasing subnational fiscal transparency, and promoting citizen participation mechanisms in budget decision-making. It would also be optimal to implement performance evaluation systems that measure the efficiency and effectiveness of public spending at the local level.

All these actions to strengthen subnational governments could constitute new lines of research, on more complex theoretical models to explain the mechanisms involved. It is also necessary to build more precise fiscal decentralisation indicators and contrast their effectiveness with respect to other institutional variables other than those used in this research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.E.P.-R.; methodology, D.E.P.-R. and P.H.-M.; software, P.H.-M.; validation, D.E.P.-R. and P.H.-M.; formal analysis, D.E.P.-R.; investigation, D.E.P.-R.; data curation, D.E.P.-R. and P.H.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.E.P.-R.; writing—review and editing, D.E.P.-R. and P.H.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors confirm that this research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in IMF’s Fiscal Decentralization Dataset at https://data.imf.org/ (accessed on 12 February 2024) and World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators | DataBank at https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worldwide-governance-indicators (accessed on 12 February 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad, Ehtisham, and Giorgio Brosio. 2006. Introduction: Fiscal federalism—A review of developments in the literature and policy. In Handbook of Fiscal Federalism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, Ehtisham, and Mercedes Garcia-Escribano. 2006. Fiscal Decentralization and Public Subnational Financial Management in Peru. Working Paper No. 2006/120. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, Junait, Shantayanan Devarajan, Stuti Khemani, and Shekhar Shah. 2006. Decentralization and Service Delivery. In Handbook of Fiscal Federalism. Edited by E. Ahmad and G. Brossio. Gloucestershire: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Akai, Nobuo, and Masayo Sakata. 2002. Fiscal decentralization contributes to economic growth: Evidence from state-level cross-section data for the United States. Journal of Urban Economics 52: 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, Eme O. 2011. Fiscal Decentralization and Social Outcomes in Nigeria European. Journal of Business and Management 3: 167–83. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, Alberto, Ricardo Hausmann, Rudolf Hommes, and Ernesto Stein. 1999. Budget Institutions and Fiscal Performance in Latin America. Working Paper 394. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank (IADB). [Google Scholar]

- Arif, Umaima, and Eatzaz Ahmad. 2020. A framework for analysing the impact of fiscal decentralization on macroeconomic performance, governance and economic growth. The Singapore Economic Review 65: 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Sarah, and Dave Haran. 2004. Back to basics: Does decentralization improve health system performance? Evidence from Ceará in north-east Brazil. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. The International Journal of Public Health 82: 822–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bahl, Roy W. 1999. Implementation Rules for Fiscal Decentralization. Working Paper No. 10. Atlanta: International Studies Program, School of Policy Studies, Georgia State University. [Google Scholar]

- Baskaran, Thushyanthan, Lars P. Feld, and Jan Schnellenbach. 2016. Fiscal federalism, decentralization, and economic growth: A meta-analysis. Economic Inquiry 54: 1445–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, Richard M., and François Vaillancourt. 1998. Fiscal decentralization in developing countries: An overview. In Fiscal Decentralization in Developing Countries. Edited by Richard M. Bird and Francois Vaillancourt. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blöchliger, Hansjörg, and Balázs Égert. 2013. Decentralisation and Economic Growth—Part 2: The Impact on Economic Activity, Productivity and Investment. OECD Working Papers on Fiscal Federalism, No. 15. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bojanic, Antonio N. 2018. The Impact of Fiscal Decentralization on Growth, Inflation, and Inequality in the Americas. Cepal Review 124: 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, Shahid Javed, Guillermo E. Perry, and William R. Dillinger. 1999. Beyond the Center, Decentralizing the STATE. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrero Mendoza, Eduardo, Laura Flamand Gómez, Claudia Santizo Rodall, and Alejandro Vega Godínez. 1997. Claroscuros del nuevo federalismo mexicano: Estrategias en la descentralización federal y capacidades en la gestión local. Gestión y Política Pública VI: 329–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrero Mendoza, Enrique. 2004. Capacidades institucionales en gobiernos subnacionales de México ¿Un obstáculo para la descentralización fiscal? Gestión y Política Pública XIII: 753–84. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Tim, George Peterson, and José Brakarz. 1991. Decentralization in LAC: National Strategies and Local Response in Planning, Spending and Management. LACTD Dissemination Note No. 5. Latin America and the Caribbean Technical Dept., Regional Studies Program. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt, Sebastian. 2008. Political accountability, fiscal conditions, and local government performance—Cross-sectional evidence from Indonesia. Public Administration and Development 28: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enikolopov, Ruben, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya. 2003. Decentralization and Political Institutions. Discussion Papers 3857. London: Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). [Google Scholar]

- Feld, Lars P., Horts Zimmermann, and Thomas Döring. 2004. Federalism, decentralization, and economic growth (No. 2004, 30). In Marburger Volkswirtschaftliche Beiträge, No. 2004, 30. Marburg: Philipps-Universität Marburg, Fachbereich Wirtschaftswissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Franzese, Robert J., Jr. 2002. Macroeconomic Policies of Developed Democracies. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gemmell, Norman, Richard Kneller, and Ismael Sanz. 2013. Fiscal decentralization and economic growth: Spending versus revenue decentralization. Economic Inquiry 51: 1915–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Jorge Ivan. 1994. Un ordenamiento territorial de corte fiscalista, en A. Cifuentes Noyes (coord.). In Diez años de descentralización, Resultados y perspectivas. Bogotá: Fundación Friedrich Ebert de Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Grilli, Vittorio, Donato Masciandaro, and Guido Tabellini. 1991. Political and monetary institutions and public financial policies in the industrial democracies. Economic Policy 6: 341–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, Imran, Sally Wallace, and Pilar Gago-de-Santos. 2020. Economic growth by means of fiscal decentralization: An empirical study for federal developing countries. Sage Open 10: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankla, Charles R. 2009. When is fiscal decentralization good for governance? Publius: The Journal of Federalism 39: 632–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankla, Charles, and William Downs. 2010. Decentralization, Governance, and the Structure of Local Political Institutions: Lessons for Reform? Local Government Studies 36: 759–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Trillo, Fausto, and Brenda Jarillo-Rabling. 2008. Is local beautiful? Fiscal decentralization in Mexico. World Development 36: 1547–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, Peter, and Yoonjoung Choi. 2010. Health system performance at the district level in Indonesia after decentralization. BMC International Health and Human Rights 10: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huther, Jeff, and Anwar Shah. 1998. Applying a Simple Measure of Good Governance to the Debate on Fiscal Decentralization. Policy Research Paper, 1894. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Iimi, Atsushi. 2005. Decentralization and economic growth revisited: An empirical note. Journal of Urban Economics 57: 449–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, K. S., Klaus Frohberg, Abay Asfaw, and Johannes P. Jütting. 2004. Modeling the Impact of Fiscal Decentralization on Health Outcomes: Empirical Evidence from India. ZEF Discussion Papers on Development Policy, No. 87. Bonn: University of Bonn, Center for Development Research (ZEF). [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, Rubio Dolores. 2011. The impact of fiscal decentralization on infant mortality rates: Evidence from OECD countries. Social Science and Medicine 73: 1401–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Hehui, Yingyi Qian, and Barry R. Weingast. 1999. Regional Decentralization and Fiscal Incentives: Federalism, Chinese Style. Working Paper. Stanford: Hoover Institution, Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2011. The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 3: 220–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghian, Peyvand. 2003. Decentralization and Public Services: The Case of Immunization. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 2989. Washington, DC: Development Research Group (DECRG) World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou, Andreas P., Leonel Muinelo-Gallo, and Oriol Roca-Sagalés. 2015. Fiscal decentralization and regional disparities: The importance of good governance. Papers in Regional Science 94: 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Justin Yifu, and Zhiqiang Liu. 2000. Fiscal decentralization and economic growth in China. Economic Development and Cultural Change 49: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvack, Jennie, Junaid Ahmad, and Richard Bird. 1998. Rethinking Decentralization in Developing Countries (English). World Bank Sector Studies Series; Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/938101468764361146/Rethinking-decentralization-in-developing-countries (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Manor, James. 1999. The Political Economy of Democratic Decentralization. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Martner, Ricardo. 2005. Indicadores fiscales en América Latina y el Caribe. Documento preparado para la Reunión de la Red de Gestión y Transparencia de la Política Pública: Efectividad del Desarrollo y Gestión Presupuestaria por Resultados, mayo de 2005. Washington, DC: Instituto Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Planificación Económica y Social (ILPES). [Google Scholar]

- Mascareño, Carlos. 2009. Descentralización y democracia en América Latina, ¿una relación directa? Revisión conceptual del estado del arte. Reforma y Democracia 45: 63–98. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Kevin M., Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. 1991. The allocation of talent: Implications for growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 106: 503–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nana, Nketcha. 2009. Expenditure Decentralization and Outcomes: Some Determinant Factors for Success from Cross Country Evidence. París: Economica. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, Deepa. 1998. Participatory rural development. In Agriculture and the Environment: Perspectives on Sustainable Rural Development. Edited by E. Lutz. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Nickson, Andrew. 2023. Decentralization in Latin America After 40 Years: Work in Progress; A Commentary Essay. Public Organiz Rev 23: 1017–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, Wallace. E. 1977. Federalismo Fiscal. Colección nuevo urbanismo. No. 25. Versión en ingles. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios de Administración Local. [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla-Rodríguez, Diego. E., Juan de Dios Jiménez-Aguilera, and Roberto Montero-Granados. 2014. Descentralización fiscal en América Latina: Impacto social y determinantes. Investigación Económica 73: 79–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla-Rodríguez, Diego. E., Juan de Dios Jiménez Aguilera, and Roberto Montero Granados. 2016. Descentralización fiscal y crecimiento económico. La experiencia reciente de América Latina. Desarrollo y Sociedad 77: 11–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Rodríguez, Raúl A., Charles R. Hankla, Jorge Martinez-Vazquez, and Eunice Heredia-Ortiz. 2020. The politics of fiscal federalism: Building a stronger decentralization theorem. Journal of Theoretical Politics 32: 605–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, Alberto, and Pablo Sanguinetti. 2001. Political determinants of intergovernmental grants: Evidence from Argentina. Economics & Politics 13: 237–56. [Google Scholar]

- Prud’homme, Rémy. 1995. On the Dangers of Decentralization. Washington, DC: The World Bank Research Observer, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Baoyun, Jorge Martinez-Vazquez, and Yongsheng Xu. 2008. The trade-off between growth and equity in decentralization policy: China’s experience. Journal of Development Economics 86: 112–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, Juan Camilo. 2004. La segunda generación de las reformas descentralistas en América Latina. Paper presented at Conferencia Anual de Ejecutivos Competitividad y Desarrollo en la Democracia, Panamá City, Panamá, March 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rezende, Fernando, and José Roberto Afonso. 2006. The Brazilian federation: Facts, challenges, and perspectives. In Federalism and Economic Reform: International Perspectives. Edited by Jessica Wallack and T. N. Srinivasan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 143–88. [Google Scholar]

- Robalino, David A., Oscar F. Picazo, and Al Voetberg. 2001. Does Fiscal Decentralization Improve Health Outcomes? Evidence from a Cross-Country Analysis. Policy Research Working Paper 2565. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Rodden, Jonathan. 2003. Reviving Leviathan: Fiscal Federalism and the Growth of Government. International Organization 57: 695–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, Andres, and Adala P. Bwire. 2005. La ineficiencia económica en los procesos de descentralización. Ekonomiaz: Revista Vasca de Economía 58: 146–75. [Google Scholar]

- Roubini, Nouriel, and Jeffrey Sachs. 1989. Government Spending and Budget Deficits: Industrial Democracies. Working Paper 2919. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Anwar. 1998. Fiscal Federalism and Macroeconomic Governance: For Better or For Worse? Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Anwar. 2004. Fiscal Decentralization in Developing and Transition Economies: Progress, Problems, and the Promise. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications, vol. 3282. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Chanchal Kumar. 2006. Decentralization Dilemma: Measuring the Degree and Evaluating the Outcome. Indian Journal of Political Science 67: 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shleifer, Andrei, and Robert. W. Vishny. 1993. Corruption. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 108: 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Ernesto, Ernesto Talvi, and Alejandro Grisanti. 1998. Institutional arrangements and fiscal performance: The Latin American experience. In Fiscal Institutions and Fiscal Performance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 103–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Robert. M. 1999. Devolution and challenge for state and local governance. In American State and Local Politics: Directions for the 21st Century. Edited by Ronald E. Weber and Paul Brace. New York: Chatham House, pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi, Vito. 1995. Fiscal federalism and decentralization: A review of some efficiency and macroeconomic aspects. In Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics 1995. Edited by Michael Bruno and Boris Pleskovic. Washington, DC: World Bank, pp. 295–316. [Google Scholar]

- Uchimura, Hiroko, and Johannes. P. Jütting. 2009. Fiscal Decentralization, Chinese Style: Good for Health Outcomes? World Development 37: 1926–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, Stefan, and Lorenz Blume. 2012. The economic effects of federalism and decentralization—A cross-country assessment. Public Choice 151: 229–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Danyang, Heng-fu Zou, and Hamid Davoodi. 1999. Fiscal decentralization and economic growth in the United States. Journal of Urban Economics 45: 228–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).