Servicification in Global Value Chains in Emerging and Developing Asian Economies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Contribution

3. Empirical Methods

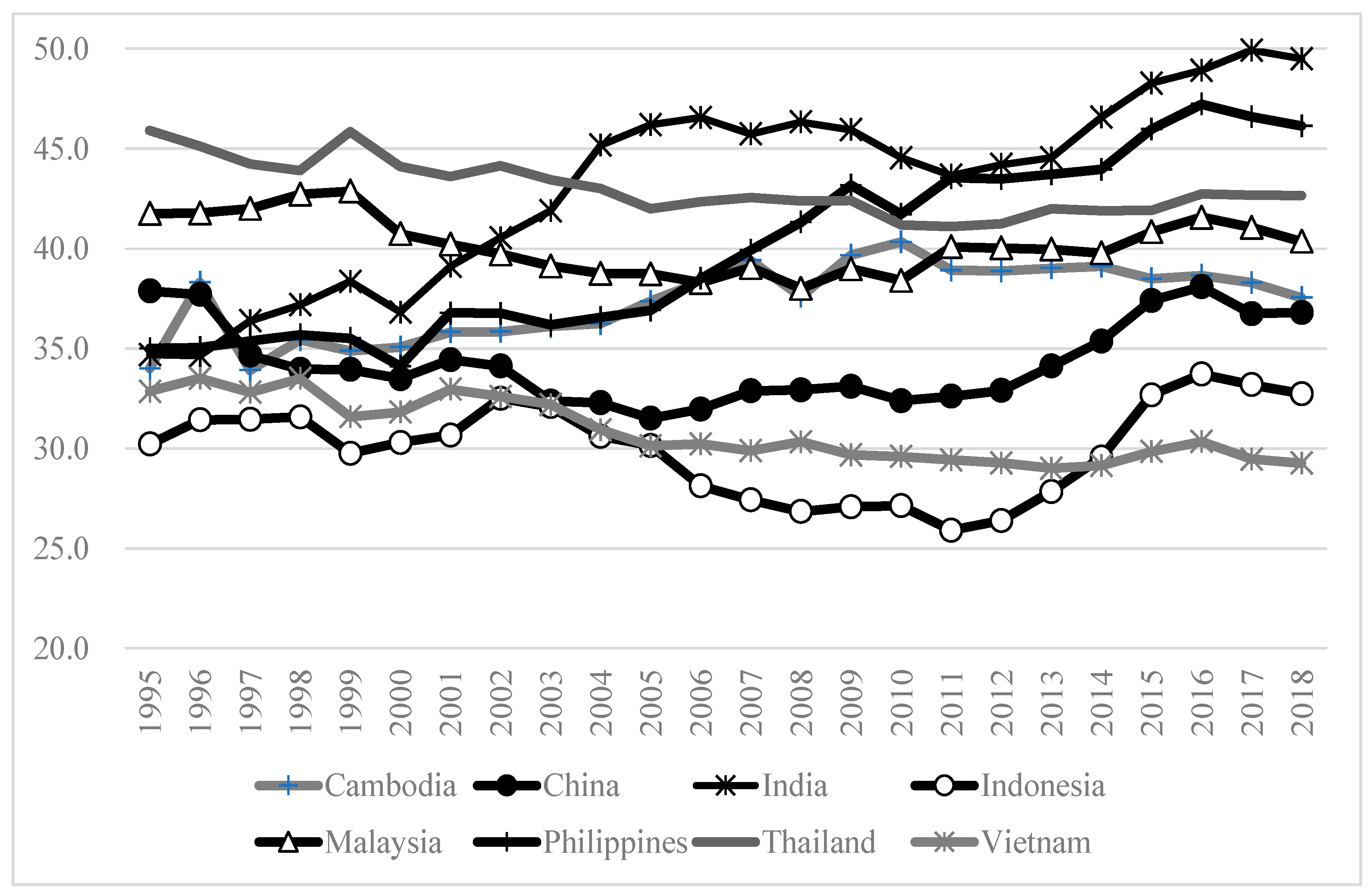

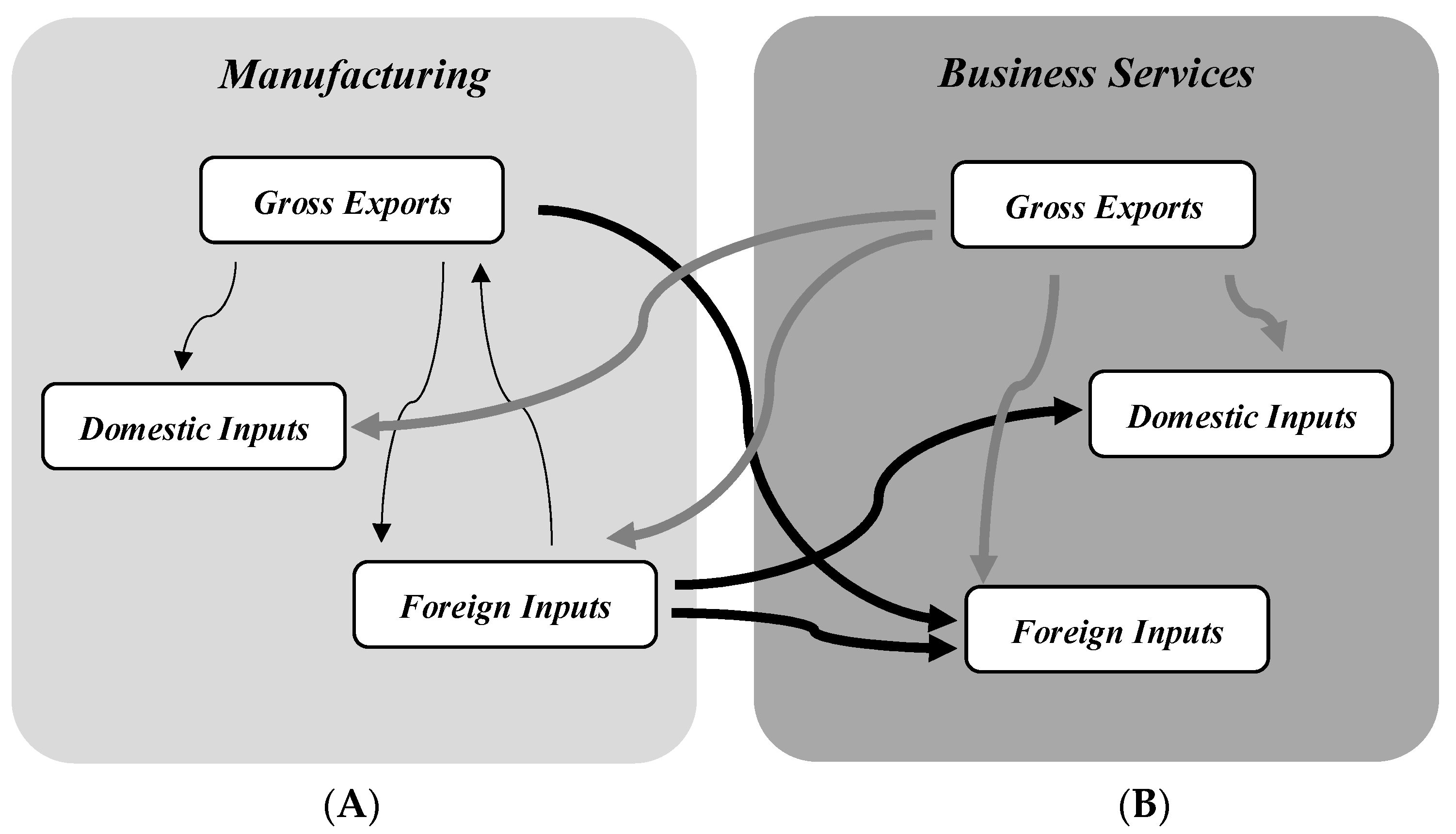

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Variables and Data

3.3. Data Property

3.4. PVAR Model Specification

4. Estimation Results and Discussion

4.1. Causalities between Business Service Inputs and Manufacturing Exports and Inputs

4.2. Causalities between Business Service Inputs and Exports and Manufacturing Inputs

4.3. Summary of Findings and Policy Implications

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | See the website: https://stats.oecd.org/ (accessed on 1 February 2024). |

| 2 | The income classification is based on World Bank’s classification. Please see https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 (accessed on 1 February 2024). |

| 3 | See the website: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/ (accessed on 1 February 2024). |

| 4 | In the variable pcy, a unit-root is rejected; however, when considering only the LLC, a weak significant level is seen. |

| 5 | See the website: https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/brief/services-trade-restrictions-database (accessed on 1 February 2024). |

References

- Alvarez, Julian B., Kristina Baris, Maverick C. Crisostomo, Janine P. de Vera, Yuning Gao, Krizia Anne V. Garay, P. B. Gonzales, Christian J. Jabagat, Angeli S. Juani, Angelo B. Lumba, and et al. 2021. Recent Trends in Global Value Chains. In Global Value Chain Development Report 2021: Beyond Production. Edited by Asian Development Bank, the Research Institute for Global Value Chains at the University of International Business and Economics, the World Trade Organization, the Institute of Developing Economies–Japan External Trade Organization and the China Development Research Foundation. Available online: https://www.adb.org/publications/global-value-chain-development-report-2021 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Baek, Nuri, Kaustubh Chahande, Kodjovi Eklou, Tidiane Kinda, Vatsal Nahata, Umang Rawat, and Ara Stepanyan. 2023. ASEAN-5: Further Harnessing the Benefits of Regional Integration amid Fragmentation Risks. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, IMF Working Papers No. WP/23/191. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, Richard, Rikard Forslid, and Tadashi Ito. 2015. Unveiling the Evolving Sources of Value Added in Exports. IDE–JETRO Joint Research Program Series. No. 161; Available online: https://www.ide.go.jp/English/Publish/Reports/Jrp/161.html (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Beverelli, Cosimo, Matteo Fiorini, and Bernard Hoekman. 2017. Services Trade Policy and Manufacturing Productivity: The Role of Institutions. Journal of International Economics 104: 166–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez, Leticia, Carmen Díaz-Mora, and Belén González-Díaz. 2023. Slowbalisation or a ‘New’ type of GVC participation? The role of digital services. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics 50: 121–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Dazhong, and Zhiguo Xiao. 2021. Producer Services and Productivity: A Global Value Chain Perspective. Review of Income and Wealth 67: 418–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, In. 2001. Unit root tests for panel data. Journal of International Money and Finance 20: 249–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Colin. 1940. The Conditions of Economic Progress. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Mora, Carmen, Rosario Gandoy, and Belén González-Díaz. 2018. Looking into global value chains: Influence of foreign services on export performance. Review of World Economics 154: 785–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, Christopher, and Hein Roelfsema. 2023. Services trade in the ASEAN region and participation in GVCs. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 28: 986–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francois, Joseph, and Bernard Hoekman. 2010. Services Trade and Policy. Journal of Economic Literature 48: 642–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Ulrich Elmar, Ivan Nygaard, Mike Morris, and Glen Robbins. 2022. Servicification of Manufacturing in Global Value Chains: Upgrading of Local Suppliers of Embedded Services in the South African Market for Wind Turbines. The Journal of Development Studies 58: 787–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, Jerry A. 1978. Specification Tests in Econometrics. Econometrica 46: 1251–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuser, Cecilia, and Aaditya Mattoo. 2017. Services Trade and Global Value Chains. In Global Value Chain Development Report 2017: Measuring and Analyzing the Impact of GVCs on Economic Development. Edited by World Bank, Institute of Developing Economies—Japan External Trade Organization, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, University of International Business and Economics and World Trade Organization. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/gvcd_report_17_e.htm (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Im, Kyung So, Mohammed H. Pesaran, and Yongcheol Shin. 2003. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics 115: 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Robert C., and Guillermo Noguera. 2017. A Portrait of Trade in Value Added over Four Decades. The Review of Economics and Statistics 99: 896–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Fukunari. 2006. International production and distribution networks in East Asia: Eighteen facts, mechanics, and policy implications. Asian Economic Policy Review 1: 326–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, Robert, Zhi Wang, and Shang-Jin Wei. 2014. Tracing Value-Added and Double Counting in Gross Exports. American Economic Review 104: 459–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordalska, Aleksandra, and Magdalena Olczyk. 2021. Linkages between services and manufacturing as a new channel for GVC development: Evidence from CEE countries. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 58: 125–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Andrew, Chien-Fu Lin, and Chia-Shang James Chu. 2002. Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of Econometrics 108: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddala, G. S., and Shaowen Wu. 1999. A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 61: 631–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nano, Enrico, and Victor Stolzenburg. 2021. The Role of Global Services Value Chains for Services-Led Development. In Global Value Chain Development Report 2021: Beyond Production. Edited by Asian Development Bank, the Research Institute for Global Value Chains at the University of International Business and Economics, the World Trade Organization, the Institute of Developing Economies–Japan External Trade Organization and the China Development Research Foundation. Available online: https://www.adb.org/publications/global-value-chain-development-report-2021 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), WTO (World Trade Organization), and World Bank Group. 2014. Global Value Chains: Challenges, Opportunities and Implications for Policy. Paper presented at the G20 Trade Ministers Meeting, Sydney, Australia, July 19. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Ying. 2020. Promotion or hindrance? The threshold effect of services on global value chains. Applied Economics Letters 27: 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, Ben. 2019. Services Policies and Manufacturing Exports. In Leveraging Services for Development: Prospects and Policies. Edited by Matthias Helble and Ben Shepherd. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, Hiroyuki, and Mon Soe Thet. 2021. Quantitative linkage between global value chains’ backward participation and logistics performance in the host country: A structural gravity model analysis of emerging ASEAN economies. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science 5: 453–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2020. World Development Report—Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organization (WTO). 2021. World Trade Report 2021: Economic Resilience and Trade. Geneva: WTO. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Description | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| mex | Gross exports: manufacturing | OECD TiVA |

| modm | Domestic industrial origin of mex: manufacturing | |

| mofm | Foreign industrial origin of mex: manufacturing | |

| mods | Domestic industrial origin of mex: total business sector services | |

| mofs | Foreign industrial origin of mex: total business sector services | |

| mods_it | Domestic industrial origin of mex: IT and other information services | |

| mofs_it | Foreign industrial origin of mex: IT and other information services | |

| mods_pr | Domestic industrial origin of mex: professional, scientific and technical activities | |

| mofs_pr | Foreign industrial origin of mex: professional, scientific and technical activities | |

| sex | Gross exports: total business sector services | |

| sodm | Domestic industrial origin of sex: manufacturing | |

| sofm | Foreign industrial origin of sex: manufacturing | |

| sods | Domestic industrial origin of sex: total business sector services | |

| sofs | Foreign industrial origin of sex: total business sector services | |

| sods_it | Domestic industrial origin of sex: IT and other information services | |

| sofs_it | Foreign industrial origin of sex: IT and other information services | |

| sods_pr | Domestic industrial origin of sex: professional, scientific and technical activities | |

| sofs_pr | Foreign industrial origin of sex: professional, scientific and technical activities | |

| pcy | GDP per capita, constant (2015) prices | UNCTAD |

| Variables | Obs. | Median | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mex | 192 | 56,505 | 362,669 | 542 | 1,985,752 |

| modm | 192 | 20,890 | 172,045 | 304 | 950,085 |

| mofm | 192 | 7235 | 28,101 | 73 | 144,141 |

| mods | 192 | 7107 | 74,214 | 52 | 440,950 |

| mofs | 192 | 6794 | 25,860 | 77 | 129,591 |

| mods_it | 192 | 44 | 1716 | 0 | 11,340 |

| mofs_it | 192 | 178 | 792 | 1 | 4685 |

| mods_pr | 192 | 81 | 4370 | 1 | 26,168 |

| mofs_pr | 192 | 614 | 2979 | 6 | 15,292 |

| sex | 192 | 22,765 | 79,381 | 248 | 394,099 |

| sodm | 192 | 1209 | 8583 | 15 | 43,641 |

| sofm | 192 | 1133 | 1919 | 28 | 9447 |

| sods | 192 | 16,258 | 59,220 | 156 | 303,352 |

| sofs | 192 | 1710 | 3154 | 29 | 15,079 |

| sods_it | 192 | 211 | 12,542 | 1 | 71,096 |

| sofs_it | 192 | 71 | 143 | 1 | 706 |

| sods_pr | 192 | 701 | 3657 | 3 | 20,940 |

| sofs_pr | 192 | 173 | 470 | 3 | 2055 |

| pcy | 192 | 2256 | 2491 | 383 | 10,778 |

| Variables | Obs. | Median | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mex | 192 | 56,505 | 362,669 | 542 | 1,985,752 |

| modm | 192 | 20,890 | 172,045 | 304 | 950,085 |

| mofm | 192 | 7235 | 28,101 | 73 | 144,141 |

| mods | 192 | 7107 | 74,214 | 52 | 440,950 |

| mofs | 192 | 6794 | 25,860 | 77 | 129,591 |

| mods_it | 192 | 44 | 1716 | 0 | 11,340 |

| mofs_it | 192 | 178 | 792 | 1 | 4685 |

| mods_pr | 192 | 81 | 4370 | 1 | 26,168 |

| mofs_pr | 192 | 614 | 2979 | 6 | 15,292 |

| sex | 192 | 22,765 | 79,381 | 248 | 394,099 |

| sodm | 192 | 1209 | 8583 | 15 | 43,641 |

| sofm | 192 | 1133 | 1919 | 28 | 9447 |

| sods | 192 | 16,258 | 59,220 | 156 | 303,352 |

| sofs | 192 | 1710 | 3154 | 29 | 15,079 |

| sods_it | 192 | 211 | 12,542 | 1 | 71,096 |

| sofs_it | 192 | 71 | 143 | 1 | 706 |

| sods_pr | 192 | 701 | 3657 | 3 | 20,940 |

| sofs_pr | 192 | 173 | 470 | 3 | 2055 |

| pcy | 192 | 2256 | 2491 | 383 | 10,778 |

| Johansen Fisher Panel Cointegration Test | ||

|---|---|---|

| Group | Trace Test | Max-Eigen Test |

| mex, modm, mofm, mods, mofs | 259.9 *** | 168.1 *** |

| mex, modm, mofm, mods_it, mofs_it | 209.8 *** | 136.3 *** |

| mex, modm, mofm, mods_pr, mofs_pr | 225.8 *** | 157.4 *** |

| sex, sodm, sofm, sods, dofs | 202.2 *** | 134.6 *** |

| sex, sodm, sofm, sods_it, dofs_it | 254.3 *** | 171.9 *** |

| sex, sodm, sofm, sods_pr, dofs_pr | 222.2 *** | 132.6 *** |

| (a) Interactions between IT service inputs and manufacturing exports and inputs. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mex | modm | mofm | mods | mods*d06 | mofs | mofs*d06 | |

| mex−1 | 1.853 *** | 0.457 * | 0.130 * | 0.073 | 0.19 | 0.162 ** | 0.211 ** |

| [3.098] | [1.755] | [1.741] | [0.858] | [1.514] | [2.394] | [2.424] | |

| modm−1 | −0.005 | 0.818 ** | −0.088 | 0.182 | 0.046 | −0.127 | −0.200 * |

| [−0.006] | [2.244] | [−0.843] | [1.516] | [0.261] | [−1.335] | [−1.646] | |

| mofm−1 | 11.216 *** | 4.989 *** | 2.303 *** | 1.280 ** | 1.438 * | 1.496 *** | 1.395 ** |

| [2.987] | [3.054] | [4.902] | [2.381] | [1.822] | [3.511] | [2.559] | |

| mods−1 | −5.588 *** | −2.589 *** | −0.510 *** | 0.287 | −0.398 | −0.514 *** | −0.517 *** |

| [−4.129] | [−4.397] | [−3.012] | [1.484] | [−1.400] | [−3.345] | [−2.631] | |

| mods*d06−1 | 2.698 ** | 1.350 ** | 0.259 | 0.155 | 0.703 ** | 0.221 | 0.176 |

| [2.001] | [2.302] | [1.536] | [0.804] | [2.483] | [1.446] | [0.901] | |

| mofs−1 | −13.703 ** | −6.031 ** | −1.781 ** | −1.798 * | −2.134 | −1.119 | −1.672 * |

| [−2.124] | [−2.149] | [−2.207] | [−1.948] | [−1.574] | [−1.529] | [−1.786] | |

| mofs*d06−1 | −3.719 * | −1.739 ** | −0.398 * | −0.182 | −0.246 | −0.325 | 0.301 |

| [−1.948] | [−2.094] | [−1.668] | [−0.668] | [−0.613] | [−1.503] | [1.087] | |

| pcy | 36.793 *** | 16.550 *** | 4.297 *** | 3.354 ** | 4.761 ** | 3.844 *** | 5.599 *** |

| [3.640] | [3.763] | [3.398] | [2.318] | [2.242] | [3.352] | [3.816] | |

| adj. R^2 | 0.99 | 0.992 | 0.974 | 0.995 | 0.99 | 0.974 | 0.960 |

| (b) Interactions between IT service inputs and manufacturing exports and inputs. | |||||||

| mex | modm | mofm | mods_it | mods_it*d06 | mofs_it | mofs_it*d06 | |

| mex−1 | 0.068 | −0.322 ** | −0.057 | −0.001 | −0.000 | −0.001 | −0.000 |

| [0.212] | [−2.300] | [−1.507] | [−0.444] | [−0.028] | [−0.756] | [−0.003] | |

| modm−1 | 1.791 *** | 1.607 *** | 0.128 * | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| [2.972] | [6.131] | [1.816] | [0.989] | [0.814] | [1.191] | [0.436] | |

| mofm−1 | 6.472 *** | 2.546 *** | 1.669 *** | −0.031 *** | −0.000 | 0.018 *** | 0.022 *** |

| [4.590] | [4.151] | [10.140] | [−2.908] | [−0.034] | [3.338] | [3.579] | |

| mods_it−1 | 13.549 | 6.66 | 0.666 | 1.083 *** | 1.280 *** | 0.065 | 0.247 ** |

| [0.592] | [0.669] | [0.249] | [6.195] | [5.383] | [0.766] | [2.453] | |

| mods_it*d06−1 | 15.936 | 8.72 | 2.021 | −0.161 | −0.018 | 0.03 | −0.091 |

| [0.882] | [1.109] | [0.958] | [−1.169] | [−0.097] | [0.443] | [−1.150] | |

| mofs_it−1 | −210.96 ** | −85.809 ** | −27.825 *** | 1.325 * | −1.395 | 0.092 | −1.103 *** |

| [−2.351] | [−2.199] | [−2.658] | [1.932] | [−1.497] | [0.276] | [−2.796] | |

| mofs_it*d06−1 | −53.719 | −23.444 | −9.343 | −0.531 | 0.585 | −0.193 | 0.749 *** |

| [−1.030] | [−1.034] | [−1.535] | [−1.333] | [1.079] | [−0.990 | [3.267] | |

| pcy | 25.092 ** | 10.586 ** | 4.430 *** | 0.149 ** | 0.063 | 0.125 *** | 0.140 *** |

| [2.531] | [2.455] | [3.829] | [1.962] | [0.611] | [3.377] | [3.207] | |

| adj. R^2 | 0.99 | 0.991 | 0.976 | 0.973 | 0.946 | 0.969 | 0.959 |

| (c) Interactions between professional service inputs and manufacturing exports and inputs. | |||||||

| mex | modm | mofm | mods_pr | mods_pr *d06 | mofs_pr | mofs_pr *d06 | |

| mex−1 | 0.887 ** | 0.008 | 0.07 | −0.013 *** | −0.013 *** | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| [2.386] | [0.047] | [1.510] | [−3.427] | [−2.801] | [1.329] | [0.983] | |

| modm−1 | 1.306 ** | 1.456 *** | −0.023 | 0.041 *** | 0.044 *** | 0 | 0.001 |

| [1.994] | [5.150] | [−0.282] | [6.289] | [5.427] | [0.048] | [0.124] | |

| mofm−1 | 5.666 *** | 2.055 *** | 1.760 *** | 0.073 *** | 0.078 *** | 0.087 *** | 0.074 *** |

| [3.324] | [2.793] | [8.313] | [4.291] | [3.698] | [3.974] | [2.580] | |

| mods_pr−1 | −28.931 | −19.286 * | −2.084 | 1.119 *** | 1.081 *** | −0.077 | 0.673 |

| [−1.097] | [−1.695] | [−0.636] | [4.248] | [3.322] | [−0.228] | [1.513] | |

| mods_pr*d06−1 | 2.466 | 7.037 | 0.357 | −0.540 ** | −0.540 * | −0.140 | −0.921 ** |

| [0.093] | [0.613] | [0.108] | [−2.032] | [−1.646] | [−0.409] | [−2.054] | |

| mofs_pr−1 | −84.806 ** | −29.662 ** | −13.567 *** | −1.176 *** | −1.473 *** | −0.532 | −1.280 ** |

| [−2.510] | [−2.034] | [−3.232] | [−3.484] | [−3.533] | [−1.225] | [−2.247] | |

| mofs_pr*d06−1 | −2.893 | −4.349 | −0.453 | 0.397 ** | 0.678 *** | 0.051 | 1.038 *** |

| [−0.171] | [−0.596] | [−0.216] | [2.350] | [3.249] | [0.234] | [3.644] | |

| pcy | 45.425 *** | 20.759 *** | 5.925 *** | 0.222 ** | 0.191 | 0.561 *** | 0.590 *** |

| [4.625] | [4.897] | [4.856] | [2.266] | [1.579] | [4.440] | [3.561] | |

| adj. R^2 | 0.991 | 0.992 | 0.976 | 0.994 | 0.991 | 0.978 | 0.963 |

| (d) Interactions between business service inputs and exports and manufacturing inputs. | |||||||

| sex | sodm | sofm | sods | sods *d06 | sofs | sofs *d06 | |

| sex−1 | 3.247 *** | 0.350 *** | 0.093 *** | 1.396 *** | 2.473 *** | 0.178 *** | 0.243 *** |

| [4.658] | [4.525] | [3.096] | [3.024] | [4.024] | [3.948] | [4.619] | |

| sodm−1 | −3.776 *** | 0.324 *** | −0.164 *** | −2.033 *** | −3.399 *** | −0.285 *** | −0.388 *** |

| [−3.504] | [2.713] | [−3.521] | [−2.848] | [−3.578] | [−4.083] | [−4.771] | |

| sofm−1 | −1.741 | 0.327 | 0.775 *** | −2.027 | −3.720 | −0.171 | −0.351 |

| [−0.457] | [0.773] | [4.711] | [−0.802] | [−1.107] | [−0.694] | [−1.220] | |

| sods−1 | −2.304 *** | −0.372 *** | −0.093 *** | −0.416 | −2.058 *** | −0.174 *** | −0.242 *** |

| [−3.203] | [−4.662] | [−3.007] | [−0.874] | [−3.246] | [−3.729] | [−4.465] | |

| sods*d06−1 | 0.0787 | 0.027 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.541 *** | −0.002 | −0.007 |

| [0.457] | [1.420] | [0.135] | [0.184] | [3.562] | [−0.208] | [−0.513] | |

| sofs−1 | −4.569 | −0.971 *** | −0.170 | −2.451 | −2.641 | 0.482 ** | −0.111 |

| [−1.546] | [−2.965] | [−1.335] | [−1.252] | [−1.014] | [2.518] | [−0.490] | |

| sofs*d06−1 | −2.082 | −0.357 * | −0.084 | −1.116 | −1.831 | −0.048 | 0.605 *** |

| [−1.204] | [−1.862] | [−1.120] | [−0.974] | [−1.201] | [−0.425] | [4.643] | |

| pcy | 5.647 ** | 0.980 *** | 0.277 *** | 3.094 ** | 5.290 ** | 0.294 * | 0.626 *** |

| [2.373] | [3.714] | [2.699 | [1.962] | [2.522] | [1.908] | [3.489] | |

| adj. R^2 | 0.987 | 0.986 | 0.958 | 0.99 | 0.983 | 0.965 | 0.959 |

| (e) Interactions among IT service inputs, business service exports, and manufacturing inputs. | |||||||

| sex | sodm | sofm | sods_it | sods_it *d06 | sofs_it | sofs_it *d06 | |

| sex−1 | 0.834 *** | −0.016 | −0.000 | 0.015 | −0.003 | 0.001 | −0.000 |

| [4.353] | [−0.711] | [−0.008] | [0.629] | [−0.096] | [0.914] | [−0.485] | |

| sodm−1 | 0.704 | 0.966 *** | −0.031 | 0.045 | 0.192 | −0.004 | 0 |

| [0.517] | [6.100] | [−0.538] | [0.259] | [0.818] | [−0.869] | [0.037] | |

| sofm−1 | 1.231 | 0.477 ** | 0.950 *** | −0.923 *** | −0.798 ** | −0.007 | 0.001 |

| [0.602] | [2.002] | [10.903] | [−3.560] | [−2.267] | [−0.911] | [0.078] | |

| sods_it−1 | 0.73 | 0.012 | 0.001 | 1.232 *** | 0.911 *** | 0.002 | 0.007 |

| [0.974] | [0.143] | [0.025] | [12.977] | [7.062] | [0.676] | [2.174] | |

| sods_it*d06−1 | −0.142 | 0.038 | 0.008 | −0.196 *** | 0.228 ** | −0.003 | −0.004 ** |

| [−0.259] | [0.602] | [0.354] | [−2.832] | [2.421] | [−1.295] | [−2.022] | |

| sofs_it−1 | 0.134 | −2.905 | −0.664 | 11.184 *** | 9.276 * | 0.722 *** | 0.064 |

| [0.004] | [−0.781] | [−0.488] | [2.762] | [1.686] | [6.296] | [0.502] | |

| sofs_it*d06−1 | −22.679 | −3.404 | −1.145 | −2.361 | 0.982 | 0.003 | 0.745 *** |

| [−0.963] | [−1.242] | [−1.143] | [−0.791] | [0.242] | [0.030] | [7.898] | |

| pcy | 4.932 * | 0.847 *** | 0.260 ** | −0.069 | −0.199 | 0.025 *** | 0.041 *** |

| [1.880] | [2.772] | [2.323] | [−0.208] | [−0.440] | [2.692] | [3.880] | |

| adj. R^2 | 0.986 | 0.984 | 0.956 | 0.991 | 0.9836 | 0.944 | 0.937 |

| (f) Interactions among professional service inputs, business service exports, and manufacturing inputs. | |||||||

| sex | sodm | sofm | sods_pr | sods_pr *d06 | sofs_pr | sofs_pr *d06 | |

| sex−1 | 1.114 *** | 0.019 | 0.012 ** | 0.035 *** | 0.039 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.004 ** |

| [8.378] | [1.201] | [2.114] | [4.916] | [4.869] | [3.566] | [2.401] | |

| sodm−1 | −0.643 | 0.777 *** | −0.065 | −0.057 | −0.033 | −0.026 *** | −0.023 * |

| [−0.631] | [6.524] | [−1.496] | [−1.051] | [−0.537] | [−2.623] | [−1.951] | |

| sofm−1 | −0.894 | 0.383 | 0.922 *** | −0.254 | −0.232 | 0.037 | 0.027 |

| [−0.284] | [1.039] | [6.880] | [−1.517] | [−1.221] | [1.230] | [0.757] | |

| sods_pr−1 | −7.245 * | −1.220 ** | −0.197 | 0.154 | −0.396 | −0.001 | −0.010 |

| [−1.726] | [−2.485] | [−1.102] | [0.690] | [−1.564] | [−0.037] | [−0.203] | |

| sods_pr*d06−1 | 5.475 | 0.988 * | 0.08 | 0.378 | 0.846 *** | −0.024 | −0.017 |

| [1.262] | [1.947] | [0.430] | [1.642] | [3.234] | [−0.579] | [−0.354] | |

| sofs_pr−1 | 24.208 | 1.714 | −0.373 | −0.563 | −0.861 | 0.388 | −0.035 |

| [0.909] | [0.550] | [−0.328] | [−0.398] | [−0.536] | [1.517] | [−0.117] | |

| sofs_pr*d06−1 | −25.141 | −3.272 | −0.392 | −0.880 | −0.606 | 0.219 | 0.815 *** |

| [−1.427] | [−1.588] | [−0.522] | [−0.940] | [−0.571] | [1.292] | [4.073] | |

| pcy | 3.604 | 0.630 ** | 0.204 ** | 0.405 *** | 0.426 *** | 0.019 | 0.046 * |

| [1.593] | [2.382] | [2.115] | [3.366] | [3.120] | [0.857] | [1.796] | |

| adj. R^2 | 0.986 | 0.984 | 0.956 | 0.981 | 0.977 | 0.963 | 0.954 |

| (a) Causalities between business service inputs and manufacturing exports and inputs. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Probability |

| mex | modm | 0 | 1 | 0.996 |

| mofm | 8.919 | 1 | 0.003 | |

| mods | 17.049 | 1 | 0.000 (negative) | |

| mofs | 4.512 | 1 | 0.034 (negative) | |

| modm | mex | 3.081 | 1 | 0.079 |

| mods | 19.335 | 1 | 0.000 (negative) | |

| mofs | 4.618 | 1 | 0.032 (negative) | |

| mofm | mex | 3.03 | 1 | 0.082 |

| mods | 9.073 | 1 | 0.003 (negative) | |

| mofs | 4.873 | 1 | 0.027 (negative) | |

| mods | mex | 0.736 | 1 | 0.391 |

| modm | 2.298 | 1 | 0.13 | |

| mofm | 5.669 | 1 | 0.017 | |

| mods*d06 | mex | 2.293 | 1 | 0.13 |

| modm | 0.068 | 1 | 0.794 | |

| mofm | 3.321 | 1 | 0.068 | |

| mofs | mex | 5.729 | 1 | 0.017 |

| modm | 1.781 | 1 | 0.182 | |

| mofm | 12.329 | 1 | 0 | |

| mofs*d06 | mex | 5.878 | 1 | 0.015 |

| modm | 2.711 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| mofm | 6.549 | 1 | 0.011 | |

| (b) Causalities between IT service inputs and manufacturing exports and inputs. | ||||

| Dependent Variable | Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Probability |

| mods_it | mex | 0.197 | 1 | 0.657 |

| modm | 0.978 | 1 | 0.323 | |

| mofm | 8.457 | 1 | 0.004 (negative) | |

| mods_it*d06 | mex | 0.001 | 1 | 0.977 |

| modm | 0.663 | 1 | 0.416 | |

| mofm | 0.001 | 1 | 0.973 | |

| mofs_it | mex | 0.572 | 1 | 0.449 |

| modm | 1.419 | 1 | 0.234 | |

| mofm | 11.144 | 1 | 0.001 | |

| mofs_it*d06 | mex | 0 | 1 | 0.997 |

| modm | 0.19 | 1 | 0.663 | |

| mofm | 12.806 | 1 | 0 | |

| (c) Causalities between professional service inputs and manufacturing exports and inputs. | ||||

| Dependent Variable | Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Probability |

| mods_pr | mex | 11.742 | 1 | 0.001 (negative) |

| modm | 39.555 | 1 | 0 | |

| mofm | 18.416 | 1 | 0 | |

| mods_pr*d06 | mex | 7.846 | 1 | 0.005 (negative) |

| modm | 29.449 | 1 | 0 | |

| mofm | 13.674 | 1 | 0 | |

| mofs_pr | mex | 1.767 | 1 | 0.184 |

| modm | 0.002 | 1 | 0.962 | |

| mofm | 15.79 | 1 | 0 | |

| mofs_pr*d06 | mex | 0.966 | 1 | 0.326 |

| modm | 0.015 | 1 | 0.901 | |

| mofm | 6.657 | 1 | 0.01 | |

| (d) Causalities among business service, IT service, and professional service inputs, business service exports, and manufacturing inputs. | ||||

| Dependent Variable | Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Probability |

| sex | sodm | 12.276 | 1 | 0.001 (negative) |

| sofm | 0.208 | 1 | 0.648 (negative) | |

| sods | 10.256 | 1 | 0.001 (negative) | |

| sodm | 2.391 | 1 | 0.122 (negative) | |

| sodm | sex | 20.478 | 1 | 0 |

| sods | 21.73 | 1 | 0.000 (negative) | |

| sofs | 8.789 | 1 | 0.003 (negative) | |

| sofm | sex | 9.584 | 1 | 0.002 |

| sods | 9.039 | 1 | 0.003 (negative) | |

| sofs | 1.782 | 1 | 0.182 (negative) | |

| sods | sex | 9.142 | 1 | 0.003 |

| sods*d06 | 16.193 | 1 | 0 | |

| sofs | 15.584 | 1 | 0 | |

| sofs*d06 | 21.338 | 1 | 0 | |

| sods_it | sex | 0.396 | 1 | 0.529 |

| sods_it*d06 | 0.009 | 1 | 0.924 | |

| sofs_it | 0.836 | 1 | 0.361 | |

| sofs_it*d06 | 0.235 | 1 | 0.628 | |

| sods_pr | sex | 24.164 | 1 | 0 |

| sods_pr*d06 | 23.711 | 1 | 0 | |

| sofs_pr | 12.718 | 1 | 0 | |

| sofs_pr*d06 | 5.766 | 1 | 0.016 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taguchi, H.; Lar, N. Servicification in Global Value Chains in Emerging and Developing Asian Economies. Economies 2024, 12, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12060125

Taguchi H, Lar N. Servicification in Global Value Chains in Emerging and Developing Asian Economies. Economies. 2024; 12(6):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12060125

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaguchi, Hiroyuki, and Ni Lar. 2024. "Servicification in Global Value Chains in Emerging and Developing Asian Economies" Economies 12, no. 6: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12060125

APA StyleTaguchi, H., & Lar, N. (2024). Servicification in Global Value Chains in Emerging and Developing Asian Economies. Economies, 12(6), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12060125