Fuel Price Networks in the EU

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Relative price stability within an OCA is important. Synchronization of fuel prices within member states helps maintain consistent relative prices of goods and services within the relevant common currency area.

- Inflation synchronization. As fuel prices are one of the major components of inflation, synchronization of fuel prices can lead to synchronization of inflation rates across the OCA as well. This has very important policy implications. Centrally implemented monetary policy by the ECB can be effective for all member states and thus be efficient and stabilizing; when fuel prices are divergent, thus rendering inflation rates divergent as well, this leads to asynchronous business cycles: some economies are facing an unemployment gap, while others are facing inflationary gaps. Under this situation, stabilizing monetary policy must be expansionary for the first and contractionary for the latter, which is of course an impossible task within a common currency area such as the Eurozone.

- Business cycle synchronization. Fuel prices play an important role in economic activity and aggregate supply. Increases in fuel prices lead to increased production costs and, thus, a lower aggregate supply. On the other hand, decreasing fuel prices lower production costs and boost aggregate supply. Both situations lead to short-term disequilibria and the need for fiscal and/or monetary policy intervention. As a result, synchronization of fuel prices enhances business cycle synchronization—an important feature of OCA and a common currency area like the Eurozone.

- Integration in goods and capital markets. This is an important criterion according to Mundell for an OCA. A well-integrated market facilitates efficient resource allocation.

- Synchronization of shocks. Positive and negative shocks must be synchronized within an OCA for the integration of the national economies within the union. Major shocks originate from fuel price changes; thus, synchronization of fuel prices is an important component of the EU as an OCA.

2. Materials and Methods

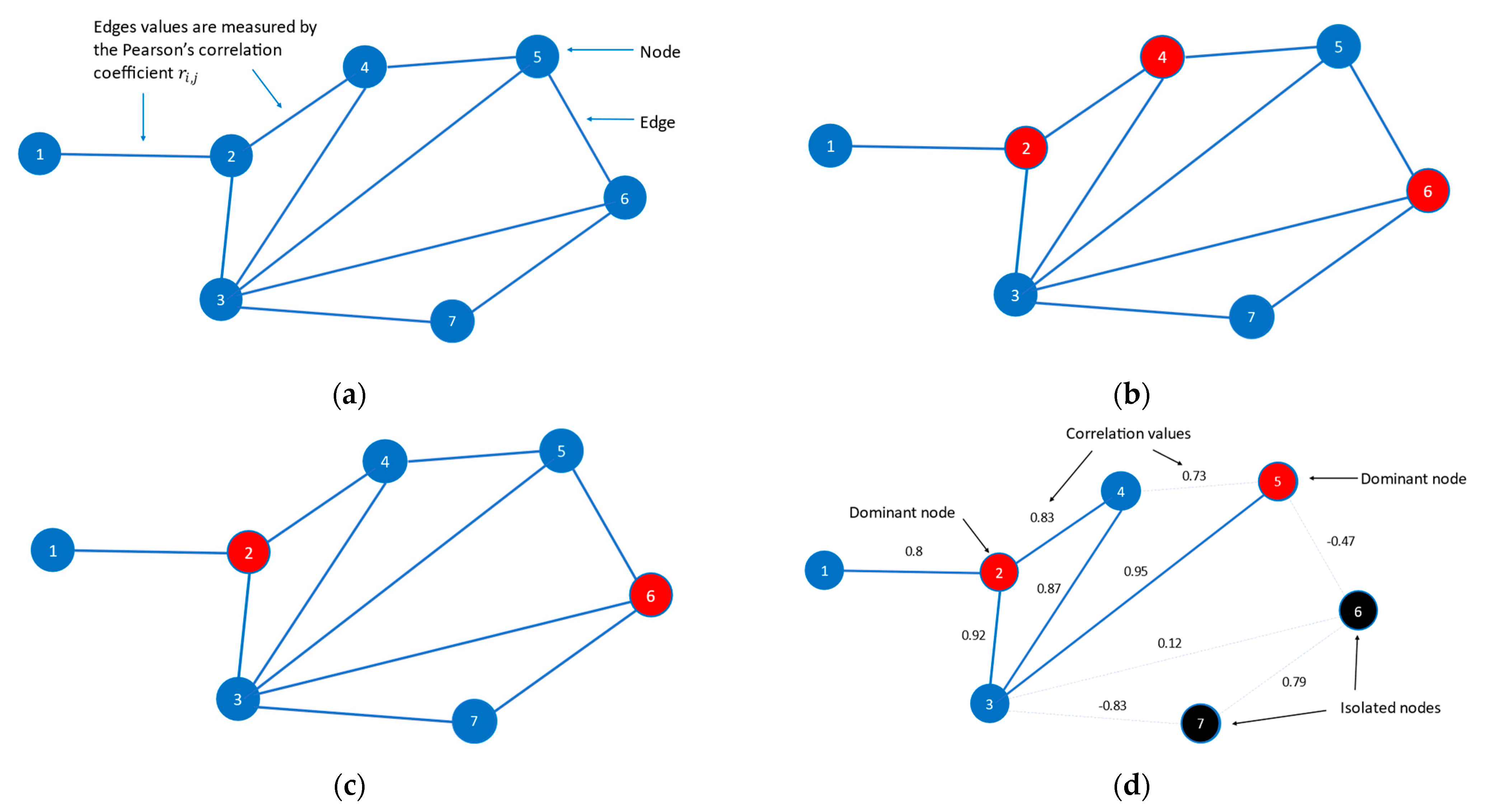

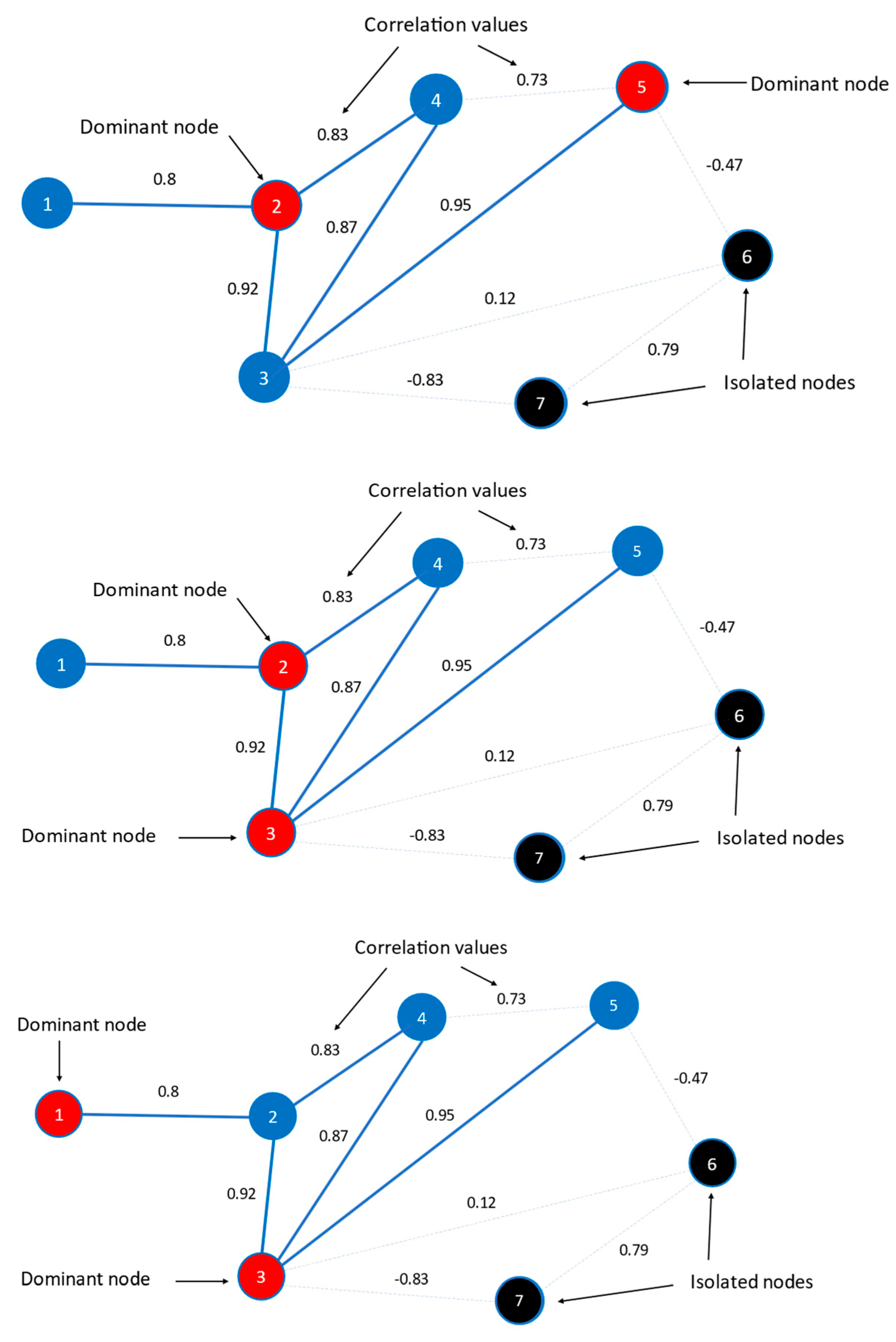

- Step 1:

- A threshold level is applied to the edges’ correlation values, resulting in the removal of edges with correlations lower than the specified threshold.

- Step 2:

- The MDS nodes are identified in the remaining network.

3. Results and Discussion

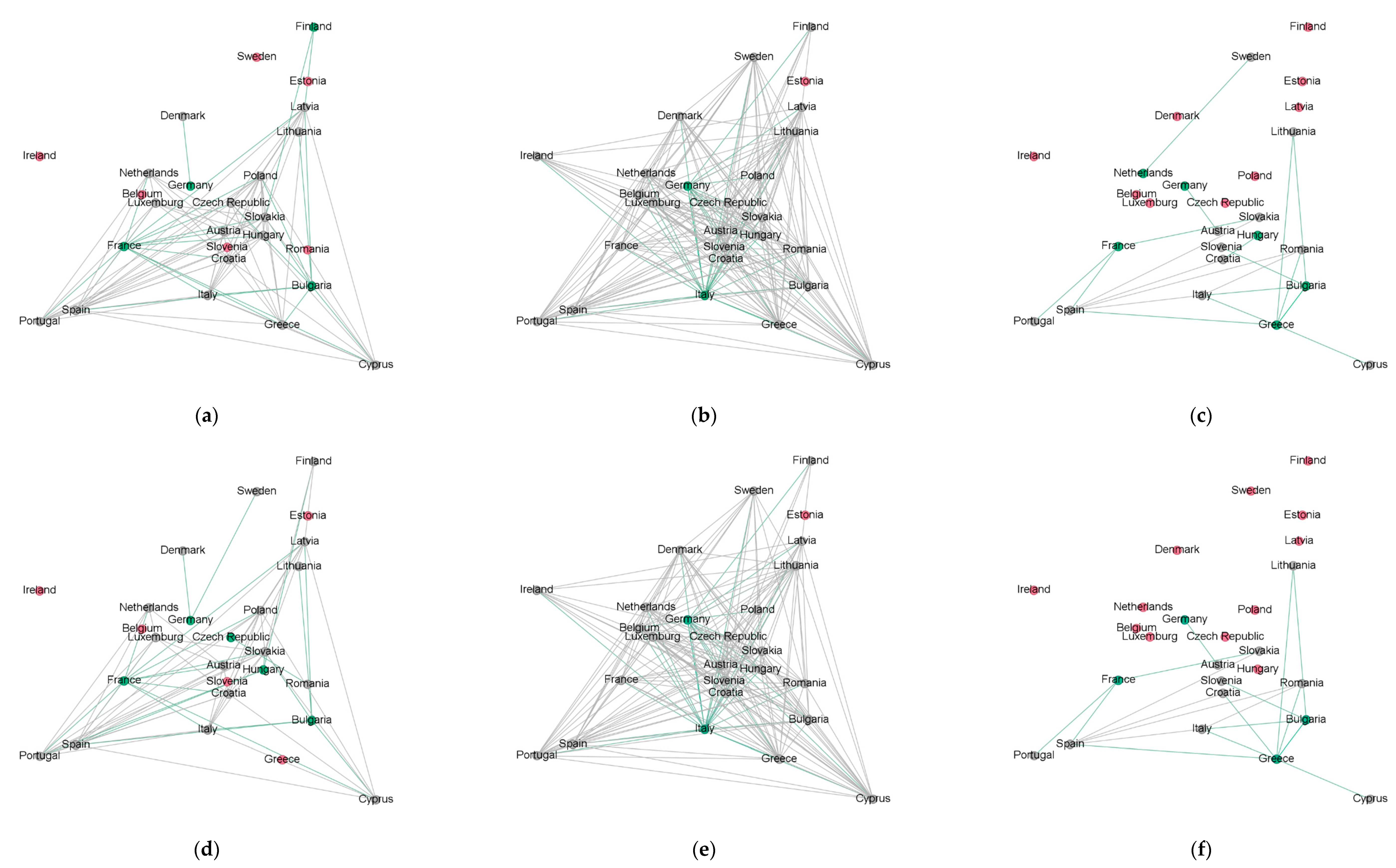

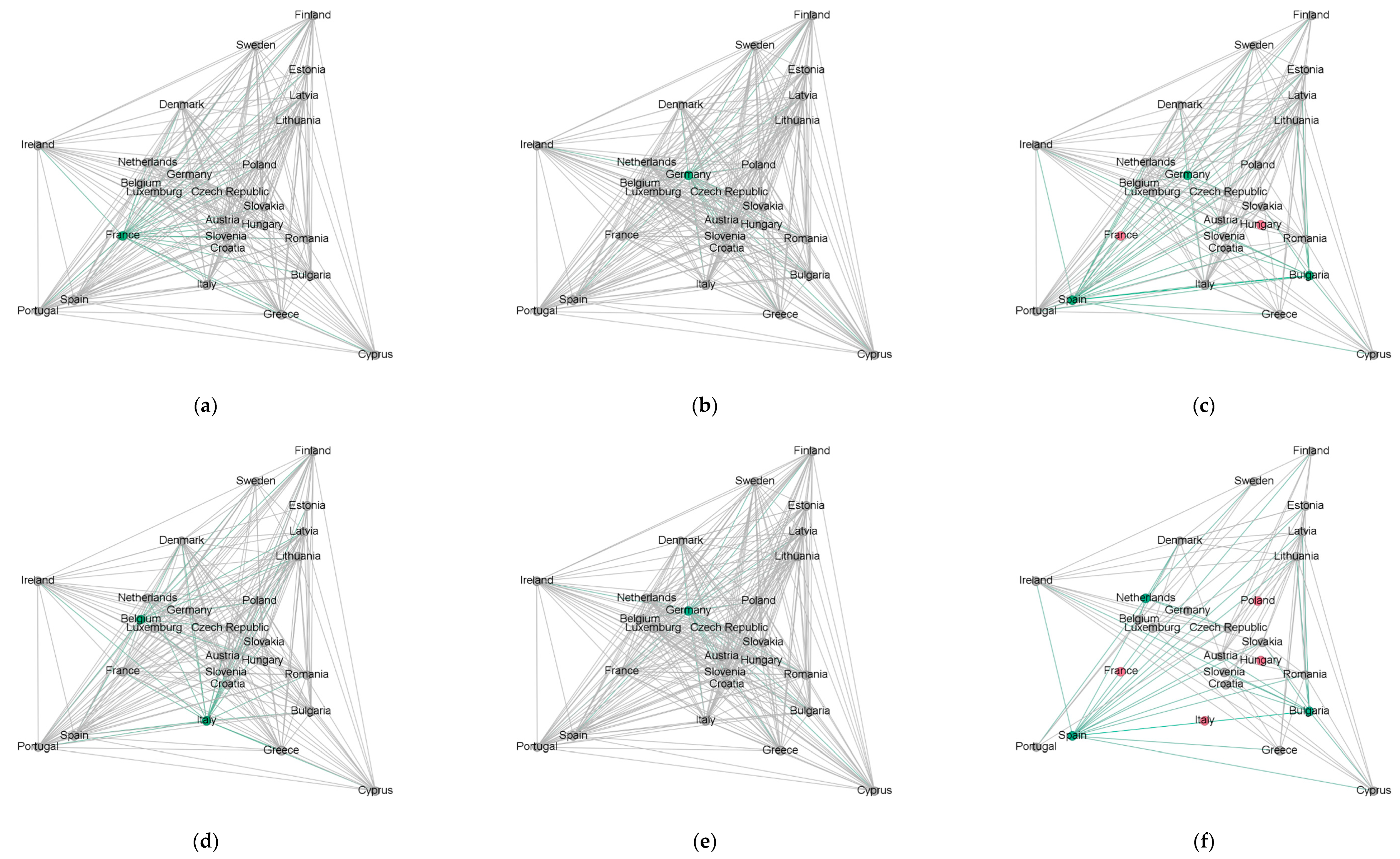

3.1. Euro Super 95 (Gasoline) Prices Net of Taxes and Duties

3.2. Euro Super 95 (Gasoline) Prices Inclusive of Taxes and Duties

3.3. Diesel Prices Net of Taxes and Duties

3.4. Diesel Prices Inclusive of Taxes and Duties

- (a)

- In general, after 2017, both the gasoline and diesel prices in the EU have a similar evolution over time (except for 2019 in the case of diesel and 2022 in both fuel cases), as described by the metrics in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. This interpretation is based on the metrics derived from the implementation of the 0.8 and 0.9 thresholds, which are rather high and strict.

- (b)

- The implementation of taxes and duties on fuels has a negative impact on the network synchronization regarding the strongly correlated upward and downward price co-movements. This is more evident in 2022, where the different fiscal policies applied in the member states lead to different trajectories in the evolution of fuel prices.

- (c)

- The case of diesel is somewhat different from that of gasoline and has two distinct features. The first one deals with the overall level of synchronization, which lies above the corresponding one of gasoline, as more edges are formed within the diesel networks. The second one has to do with the metrics in 2019, when they take a sharp turn for the worse. Given that the EU diesel consumption in 2019 remained stable compared to 2018 (data from the European Commission’s Energy website (Weekly Oil Bulletin (europa.eu)), it is rather unlikely that consumption influenced and caused the shift observed in 2019. It is also not possible that natural gas could have caused any turbulence in the diesel market (due to its role as an input in the refining process and simultaneously as a fuel that can be replaced with diesel in certain situations), as the 2019 prices for both household and non-household consumers are more or less at the same level as in 2018, according to the Eurostat natural gas price statistics. In the absence of any other event in 2019 that could potentially cause such a change in the metrics, it is possible that the observed sparser diesel network may point to different strategies of the oil companies across the EU in terms of profit margins.

- (d)

- Compared to the previous years, the high network density and the corresponding small TW-MDS size observed in 2021 for both fuels—whether net or including taxes and duties—reveals something quite interesting: the member states demonstrate a uniform behavior in terms of the price evolution, even for the remarkably high imposed threshold of 0.9. The specific status is more intense in the diesel network and seems to hold to a considerable extent also in 2020. This can be attributed to the pandemic outbreak that had a horizontal impact across all countries and the consequent measures imposed by governments, which acted in a coordinated manner to deal with the situation. The restriction of citizens’ movement and almost every human activity imposed in 2020 led to a dramatic decrease in fuel demand across all of Europe. In a way, the markets became equivalent to each other. All of the characteristics that shaped the market structures, and may have differentiated the individual European markets from each other in the previous years, were no longer in play, leading to a situation that in a sense could be described as “market homogeneity”. The same holds for 2021 as well. Several restrictions remained in place across the member states despite the recovery, since this was controlled and limited due to the fact that the economies recovered in a gradual and restrained way. At the same time, another factor that maintained the balance regarding the economies’ recovery was the ongoing supply disruptions that all countries suffered. However, the conditions in 2022 were different; the economies opened up at a full scale and reverted to the previous state, where the markets were characterized by features that were not common across all member states. At the same time, the eruption of war between Russia and Ukraine and the consequent turmoil in the oil market did not affect all states to the same extent. These two events may provide an explanation for the deterioration in metrics in 2022 that is observed across all four tables above. It seems that the pandemic outbreak and the Russo-Ukrainian war affected the fuel price co-movements across Europe, but in different directions. The former pushed countries further towards similar behavior, while the latter acted in the opposite direction, reducing the high level of common behavior the countries had previously experienced.

- (e)

- The imposition of a strict threshold has an interesting consequence regarding the formation of neighborhoods. The member states that end up being neighbors display an almost identical behavior. Although it is not a general rule for all neighborhoods, some of the neighborhoods formed in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2022 (after the 0.9 threshold application) are composed of countries that seem to be geographical neighbors, indicating a strong relationship between them and a common behavior in terms of price evolution17.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | Several factors involved in the supply–demand interaction are production/exploration capacity, reserves, technological developments, refining capacity, distribution, geopolitical tensions, natural disasters, etc. |

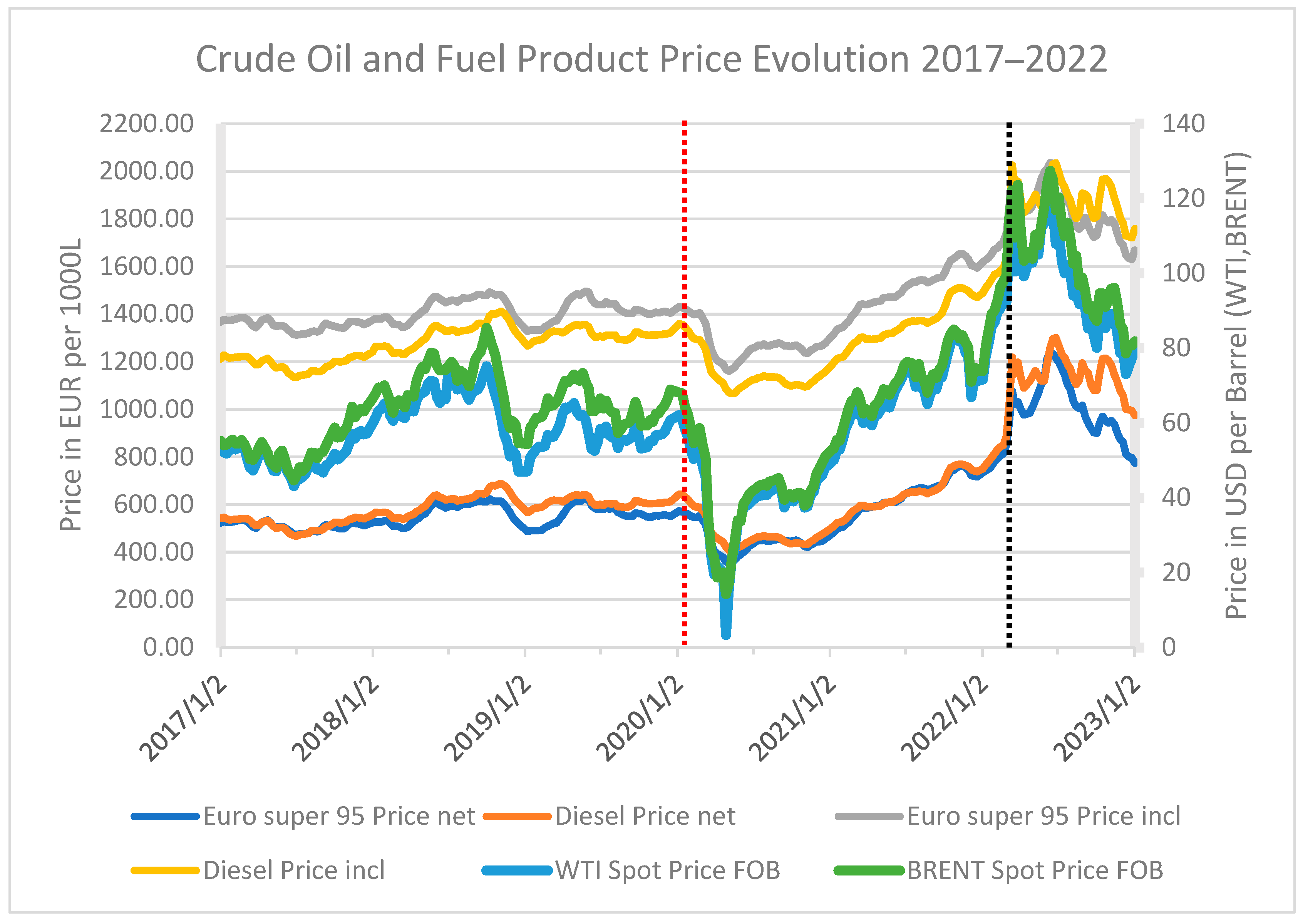

| 2 | This was the case in March–April of 2020, just after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Government-imposed restrictions on citizen movement resulted in reduced oil demand which, combined with inadequate storage capacity, contributed to the sharp decline in crude oil prices (Figure 1). |

| 3 | The six years mentioned are the ones on which the current research was conducted. |

| 4 | EU energy consumption data are available until 2021. |

| 5 | The law imposes the goal of making the EU carbon neutral by 2050 (while some emissions may continue to exist, they should be balanced through carbon capture mechanisms, such as soil and forest management). This commitment involves reducing the dependence on oil, within a reliable framework to ensure that the economic growth and social welfare are not jeopardized. Within this context, vehicles with internal combustion engines will continue to circulate. However, from 2035 onwards, it is obligatory for all new passenger cars and light commercial vehicles that enter the market to be zero-CO2-emitting vehicles, for the EU CO2 goal in 2050 to be met ((Regulation (EU) 2023/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 April 2023 amending Regulation (EU) 2019/631 as regards strengthening the CO2 emission performance standards for new passenger cars and new light commercial vehicles in line with the Union’s increased climate ambition (Text with EEA relevance) EUR-Lex-32023R0851-EN-EUR-Lex (europa.eu)). |

| 6 | The market share of electric vehicles—either BEVs (battery electric vehicles) or PHEVs (plug-in hybrid electric vehicles)—has been gradually increasing over the years, though is still low. According to data from the European Environment Agency, in 2022, only one out of five new car registrations in the EU is regarded an electric vehicle. |

| 7 | Downstream operations refer to the production and sale of finished products to consumers. In the oil industry, downstream products are those that come from the crude oil refining process, such as diesel and gasoline. |

| 8 | In their research, Gharib et al. (2021) study the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on crude oil, diesel, and gasoline prices in 2020. They find that while diesel and gasoline prices are primarily driven by fundamental factors, crude oil prices encounter a negative bubble. |

| 9 | However, persistent supply disruptions continued to impact various sectors. |

| 10 | According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, on average from the U.S. petroleum refineries, gasoline is produced with a yield of about 46.67% from crude oil, while diesel has an approximate yield of 29.98% (averaged over the 2017–2022 period). These yields fluctuate seasonally and geographically as refiners adapt their operations to meet varying fuel demands. |

| 11 | Malta, although it is a member state of the EU, is excluded from the dataset due to its policy on oil price stability at the pumps that was introduced in 2013. Owing to this policy, the oil prices did not fluctuate across long time periods in contrast to the international oil price fluctuations. Therefore, the presence of Malta in the dataset does not serve the purpose of the current research. The UK is also excluded from the dataset, as it withdrew from the EU in 2020. |

| 12 | As stated within the Weekly Oil Bulletin (europa.eu), “The prices communicated by the Member States are the prices most frequently charged, based on a weighted average”. |

| 13 | Due to the price fluctuations, it is plausible that not all edge values remain stable across time. |

| 14 | Given that each isolated node represents solely itself and thus is not represented by any other node, in a sense, it is a dominant node as well. However in the current research, in order for any confusion to be avoided, such nodes are described as isolated nodes. |

| 15 | The density calculation is directly affected by the threshold level. Although in its initial setup, the network of the current study is complete, after the threshold imposition on the edge values, several edges are removed from the network. Thus, Et counts the edges that survived the thresholding step. |

| 16 | See also the penultimate paragraph in “Introduction” where it is stated that “…at large, prices in both the diesel and gasoline markets are expected to move in the same direction”. |

| 17 | All relevant detailed results are available upon request. |

| 18 | This fact brings to the surface the challenges related to security of supply risks that might emerge, due to the persistent high import dependency of the European Union on crude oil and petroleum products over time, according to the Eurostat data for energy import dependency. Although this dependency decreased in 2021, it still remains at elevated levels. This fact becomes even more important under the consideration that a significant portion of the European Union’s imported oil originates from geopolitically unstable regions, including countries like Libya, Iraq, and Russia. |

| 19 | The graphs were created using the Open Graph Viz Platform Gephi (https://gephi.org, accessed on 21 November 2023). |

| 20 | A dominant node is by definition an interconnected one. However, in the visual network representation, it is colored green in order to be distinguished from the rest of the interconnected nodes. |

References

- Akhmedjonov, Alisher, and Chi Keung Lau. 2012. Do energy prices converge across Russian regions? Economic Modelling 29: 1623–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, Nicholas, and Grigorios Vouzavalis. 2018. Asymmetric pass through of oil prices to gasoline prices: Evidence from a new country sample. Energy Policy 114: 519–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asane-Otoo, Emmanuel, and Bernhard C. Dannemann. 2022. Rockets and Feathers Revisited: Asymmetric Retail Gasoline Pricing in the Era of Market Transparency. Energy Journal 43: 103–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhat, Mohcine, Jaume Rosselló, and Andreu Sansó. 2022. Price transmission between oil and gasoline and diesel: A new measure for evaluating time asymmetries. Energy Economics 106: 105766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Julie, Michael Owyang, and E. Katarina Vermann. 2021. Regional Gasoline Price Dynamics. Review 103: 3885398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergantino, Angela S., Claudia Capozza, and Mario Intini. 2020. Empirical investigation of retail fuel pricing: The impact of spatial interaction, competition and territorial factors. Energy Economics 90: 104876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettendorf, Leon, Stéphanie A. van der Geest, and Gerard H. Kuper. 2009. Do daily retail gasoline prices adjust asymmetrically? Journal of Applied Statistics 36: 385–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragoudakis, Zacharias, Stavros Degiannakis, and George Filis. 2020. Oil and pump prices: Testing their asymmetric relationship in a robust way. Energy Economics 88: 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, Markus, Haidi Hong, and Joaquin Vespignani. 2023. Regulation of Petrol and Diesel Prices and Their Effects on GDP Growth: Evidence from China. CAMA Working Paper 17/2023. Canberra: Centre for Applied Macroeconomic Analysis, Crawford School of Public Policy, The Australian National University. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas, Jeisson, Luis H. Gutiérrez, and Jesús Otero. 2017. Investigating diesel market integration in France: Evidence from micro data. Energy Economics 63: 314–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesnes, Matthew. 2016. Asymmetric Pass-Through in U.S. gasoline prices. Energy Journal 37: 153–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, Sara, and Mohamad B. Karaki. 2023. Do increases in gasoline prices cause higher food prices? Energy Economics 127: 107066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovern, Jonas, Johannes Frank, Alexander Glas, Lena Sophia Müller, and Daniel Perico Ortiz. 2023. Estimating pass-through rates for the 2022 tax reduction on fuel prices in Germany. Energy Economics 126: 106948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, Axel, and Tim Krieger. 2008. Do prices for petroleum products converge in a unified Europe with non-harmonized tax rates? Energy Journal 29: 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drolsbach, Chiara Patricia, Maximilian Maurice Gail, and Phil-Adrian Klotz. 2023. Pass-through of temporary fuel tax reductions: Evidence from Europe. Energy Policy 183: 113833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ederington, Louis H., Chitru S. Fernando, Thomas K. Lee, Scott C. Linn, and Huiming Zhang. 2021. The relation between petroleum product prices and crude oil prices. Energy Economics 94: 105079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib, Cheima, Salma Mefteh-Wali, Vanessa Serret, and Sami Ben Jabeur. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on crude oil prices: Evidence from Econophysics approach. Resources Policy 74: 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Mark J., Jesús Otero, and Theodore Panagiotidis. 2021. Convergence in retail gasoline prices: Insights from Canadian cities. Annals of Regional Science 68: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Qiang, and Ying Fan. 2016. Evolution of the world crude oil market integration: A graph theory analysis. Energy Economics 53: 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, Stelios, Yannis Panagopoulos, and Prodromos Vlamis. 2015. Are unleaded gasoline and diesel price adjustments symmetric? A comparison of the four largest EU retail fuel markets. Economic Modelling 48: 281–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Jian-yu “Fisher”, Martin Dresner, and Yuliang Yao. 2014. An empirical analysis of the impact of fuel costs on the level and distribution of manufacturing inventory in the United States. Transportation Journal 53: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, Lutz, and Xiaoqing Zhou. 2022. The impact of rising oil prices on U.S. inflation and inflation expectations in 2020–23. Energy Economics 113: 106228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kpodar, Kangni, and Boya Liu. 2022. The distributional implications of the impact of fuel price increases on inflation. Energy Economics 108: 105909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoufek, Ladislav, and Petra Lunackova. 2015. Rockets and feathers meet Joseph: Reinvestigating the oil-gasoline asymmetry on the international markets. Energy Economics 49: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milewska, Beata, and Dariusz Milewski. 2022. Implications of Increasing Fuel Costs for Supply Chain Strategy. Energies 15: 6934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundell, Robert A. 1961. A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas. The American Economic Review 51: 657–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mutascu, Mihai Ioan, Claudiu Tiberiu Albulescu, Nicholas Apergis, and Cosimo Magazzino. 2022. Do gasoline and diesel prices co-move? Evidence from the time–frequency domain. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29: 68776–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owyang, Michael T., and E. Katarina Vermann. 2014. Rockets and Feathers: Why Don’t Gasoline Prices Always Move in Sync with Oil Prices? St. Louis: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Publications. Available online: https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/october-2014/rockets-and-feathers-why-dont-gasoline-prices-always-move-in-sync-with-oil-prices (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Papadimitriou, Theophilos, Periklis Gogas, and Fotios Gkatzoglou. 2020. The evolution of the cryptocurrencies market: A Complex Networks approach. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 376: 112831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, Theophilos, Periklis Gogas, and Fotios Gkatzoglou. 2022. The Convergence Evolution in Europe from a Complex Networks Perspective. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, Theophilos, Periklis Gogas, Georgios Sarantitis, and Maria Matthaiou. 2014. Analysis of Network Topology Using the Threshold-Minimum Dominating Set. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiteri, Gianfranco, James Fielding, Michaela Diercke, Christine Campese, Vincent Enouf, Alexandre Gaymard, Antonino Bella, Paola Sognamiglio, Maria José Sierra Moros, Antonio Nicolau Riutort, and et al. 2020. First cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the WHO European Region, 24 January to 21 February 2020. Eurosurveillance 25: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvankulov, Farrukh, Marco Chi Keung Lau, and Fatma Ogucu. 2012. Price regulation and relative price convergence: Evidence from the retail gasoline market in Canada. Energy Policy 40: 325–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiezzi, Silvia, and Stefano F. Verde. 2016. Differential demand response to gasoline taxes and gasoline prices in the U.S. Resource and Energy Economics 44: 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Nigel. 2023. Conflict in Ukraine: A Timeline (2014–Present). London: House of Commons Library. [Google Scholar]

- Wlazlowski, Szymon, Monica Giulietti, Jane Binner, and Costas Milas. 2009. Price dynamics in European petroleum markets. Energy Economics 31: 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingbagba, Mark, Rubens Nunes, and Muriel Fadairo. 2020. The impact of diesel price on upstream and downstream food prices: Evidence from São Paulo. Energy Economics 85: 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Austria | 14 | Ireland |

| 2 | Belgium | 15 | Italia |

| 3 | Bulgaria | 16 | Latvia |

| 4 | Croatia | 17 | Lithuania |

| 5 | Cyprus | 18 | Luxemburg |

| 6 | Czech Republic | 19 | Netherlands |

| 7 | Denmark | 20 | Poland |

| 8 | Estonia | 21 | Portugal |

| 9 | Finland | 22 | Romania |

| 10 | France | 23 | Slovakia |

| 11 | Germany | 24 | Slovenia |

| 12 | Greece | 25 | Spain |

| 13 | Hungary | 26 | Sweden |

| Metrics | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| threshold | 0.8 | Density | 0.42 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 0.82 |

| Dominant Nodes | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Isolated Nodes | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Interconnected Nodes | 21 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 25 | ||

| 0.9 | Density | 0.14 | 0.46 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.94 | 0.57 | |

| Dominant Nodes | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Isolated Nodes | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Interconnected Nodes | 16 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 26 | 23 |

| Metrics | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| threshold | 0.8 | Density | 0.35 | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.56 |

| Dominant Nodes | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Isolated Nodes | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Interconnected Nodes | 23 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 24 | ||

| 0.9 | Density | 0.10 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.93 | 0.25 | |

| Dominant Nodes | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Isolated Nodes | 11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | ||

| Interconnected Nodes | 15 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 20 |

| Metrics | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| threshold | 0.8 | Density | 0.66 | 0.95 | 0.30 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

| Dominant Nodes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Isolated Nodes | 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Interconnected Nodes | 25 | 26 | 19 | 26 | 26 | 25 | ||

| 0.9 | Density | 0.28 | 0.67 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 0.54 | |

| Dominant Nodes | 4 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Isolated Nodes | 6 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Interconnected Nodes | 20 | 25 | 17 | 26 | 26 | 24 |

| Metrics | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| threshold | 0.8 | Density | 0.62 | 0.96 | 0.28 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.67 |

| Dominant Nodes | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Isolated Nodes | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Interconnected Nodes | 24 | 26 | 20 | 26 | 26 | 25 | ||

| 0.9 | Density | 0.21 | 0.61 | 0.06 | 0.75 | 0.98 | 0.30 | |

| Dominant Nodes | 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Isolated Nodes | 5 | 1 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 4 | ||

| Interconnected Nodes | 21 | 25 | 14 | 26 | 26 | 22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gkatzoglou, F.; Papadimitriou, T.; Gogas, P. Fuel Price Networks in the EU. Economies 2024, 12, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12050102

Gkatzoglou F, Papadimitriou T, Gogas P. Fuel Price Networks in the EU. Economies. 2024; 12(5):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12050102

Chicago/Turabian StyleGkatzoglou, Fotios, Theophilos Papadimitriou, and Periklis Gogas. 2024. "Fuel Price Networks in the EU" Economies 12, no. 5: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12050102

APA StyleGkatzoglou, F., Papadimitriou, T., & Gogas, P. (2024). Fuel Price Networks in the EU. Economies, 12(5), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12050102