A Systematic Review of Industry 4.0 Technology on Workforce Employability and Skills: Driving Success Factors and Challenges in South Asia

Abstract

1. Introduction

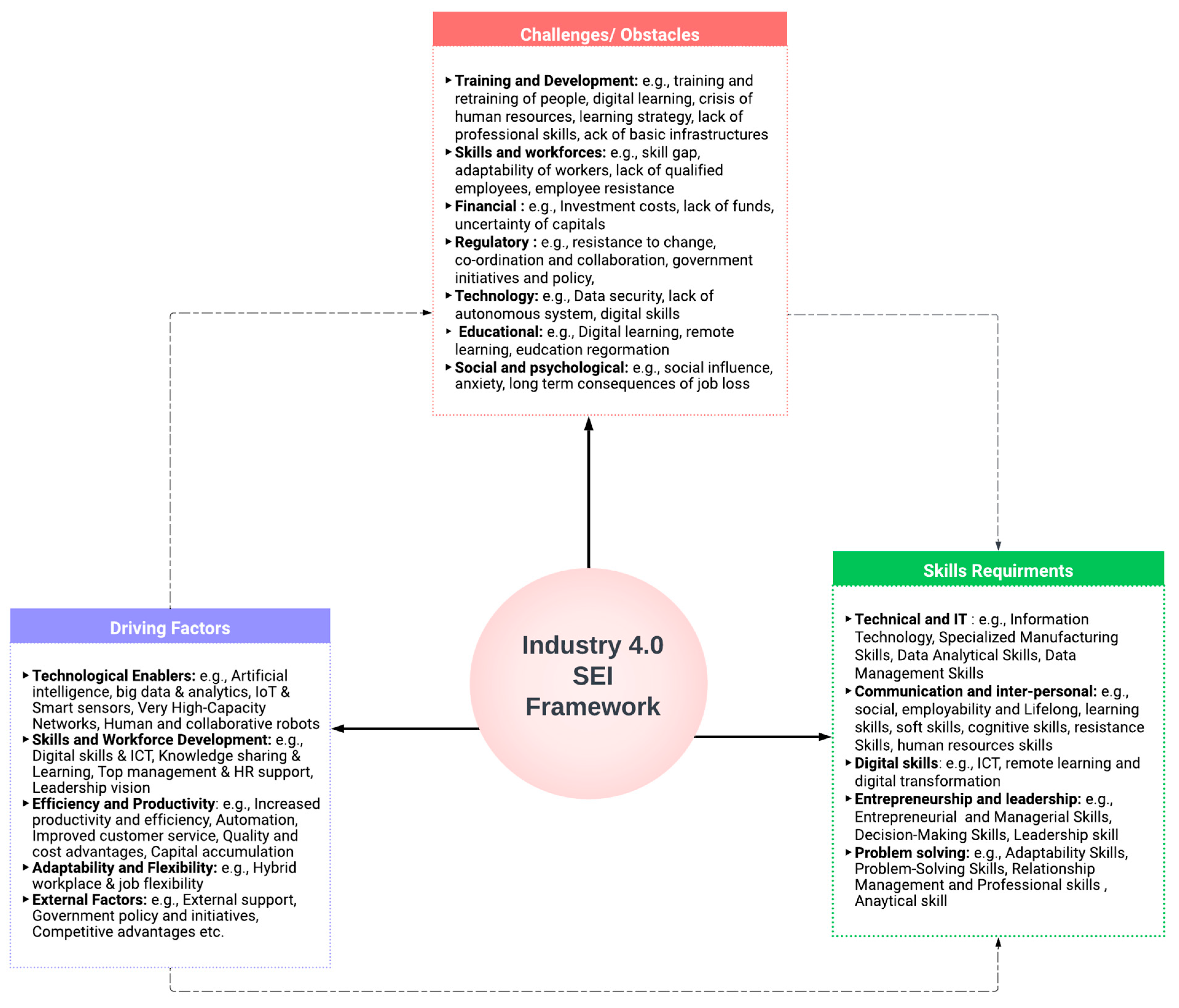

- RQ1: What are the key driving factors contributing to the success of I4.0 technology implementation in South Asia?

- RQ2: What challenges exist regarding the adoption of I4.0 technologies in the region, and how do they impact the labor market and workforce skills?

- RQ3: What are the key skill requirements and gaps resulting from the integration of I4.0 technologies?

2. Literature Reviews

2.1. Concept of Industry 4.0

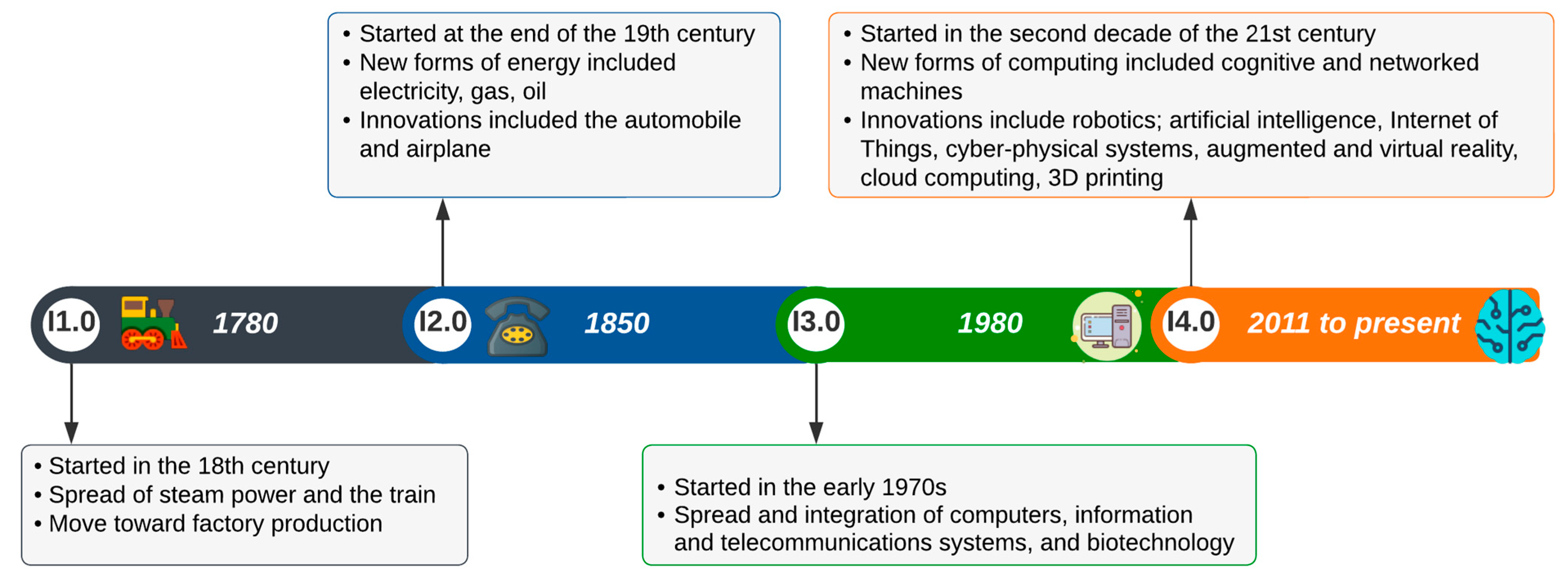

2.2. Historical Overview of the Industrial Revolution

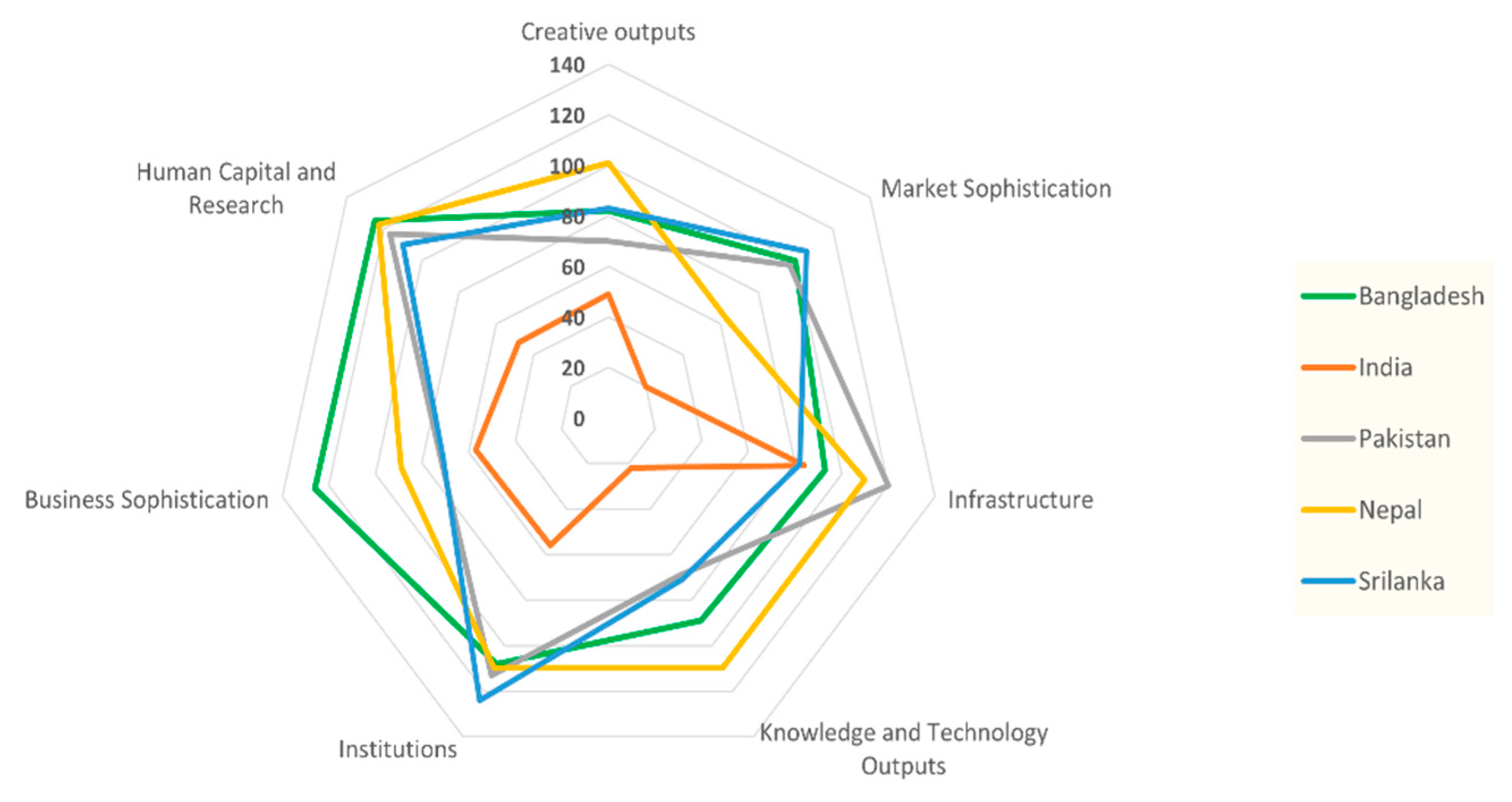

2.3. South Asia and Industry 4.0

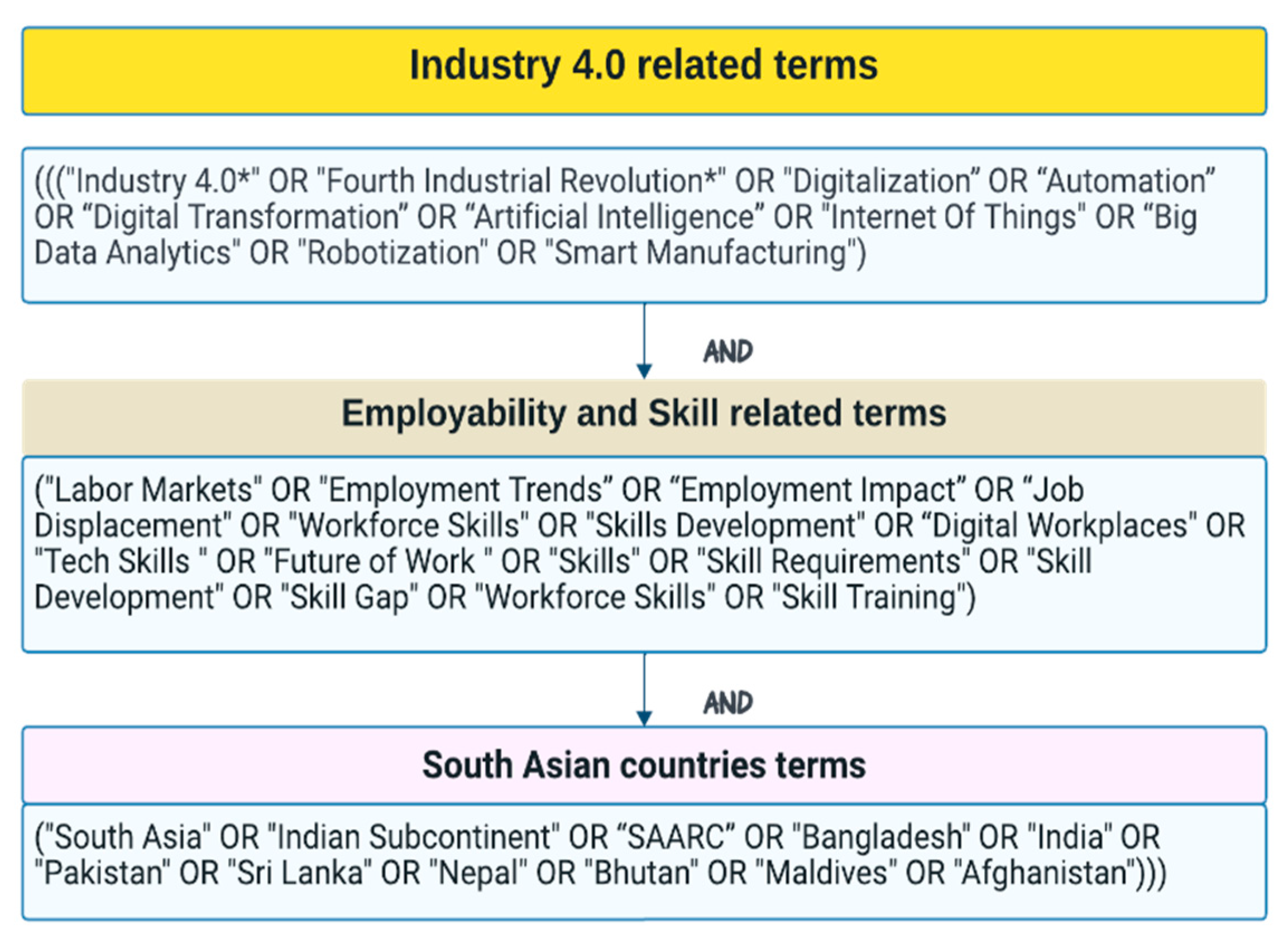

3. Methodology

3.1. Identification

3.2. Screening

3.3. Inclusion

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

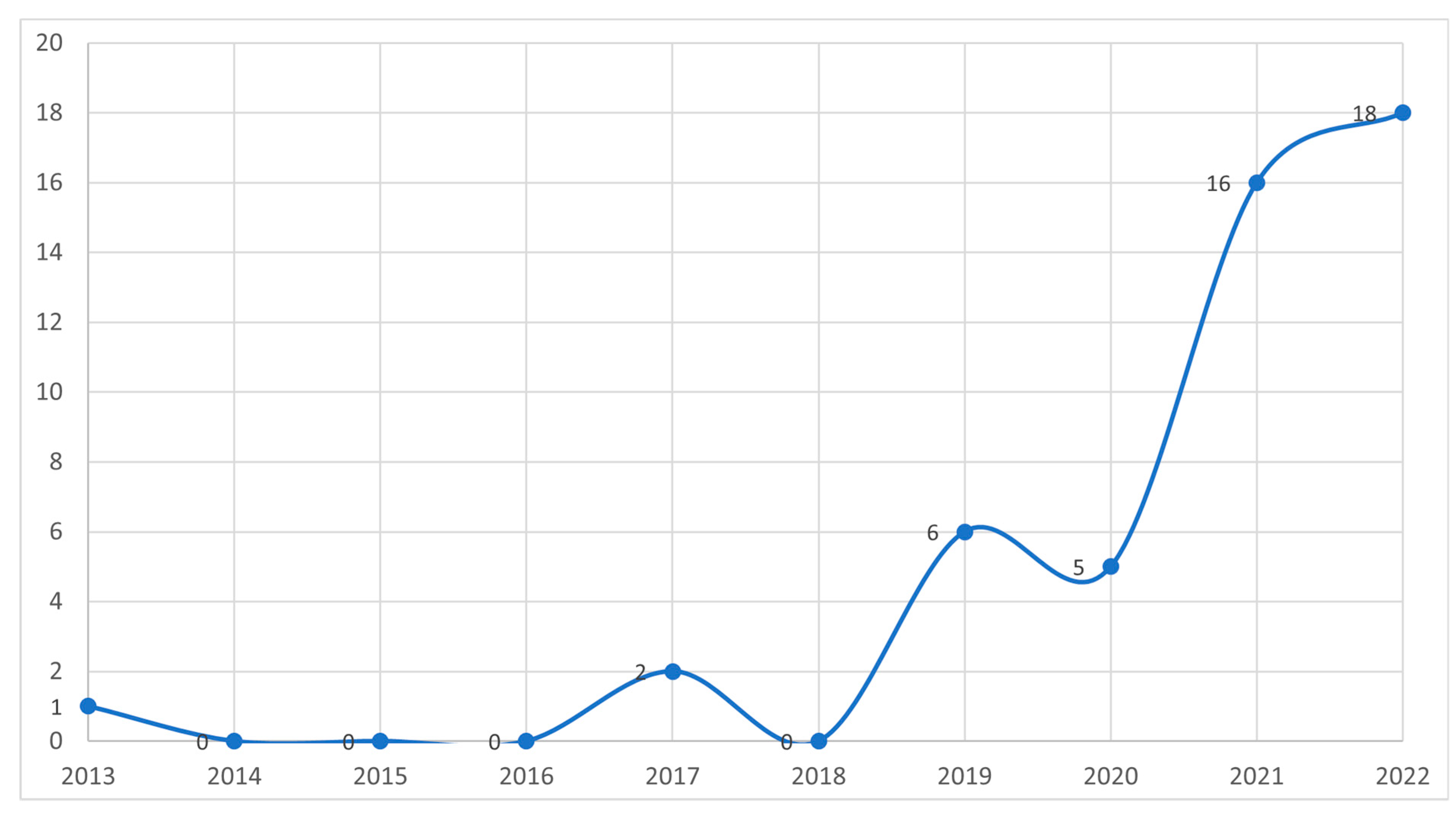

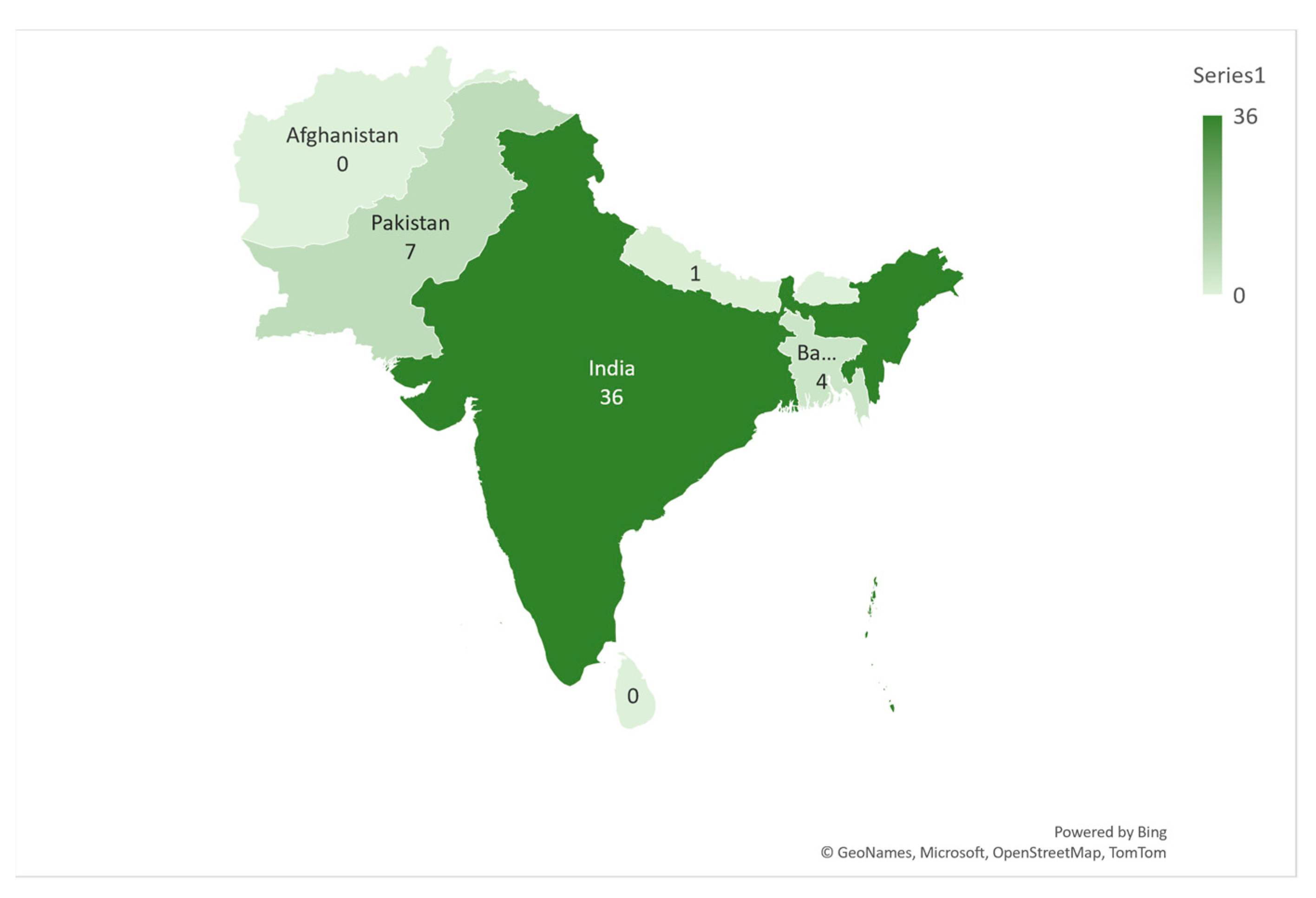

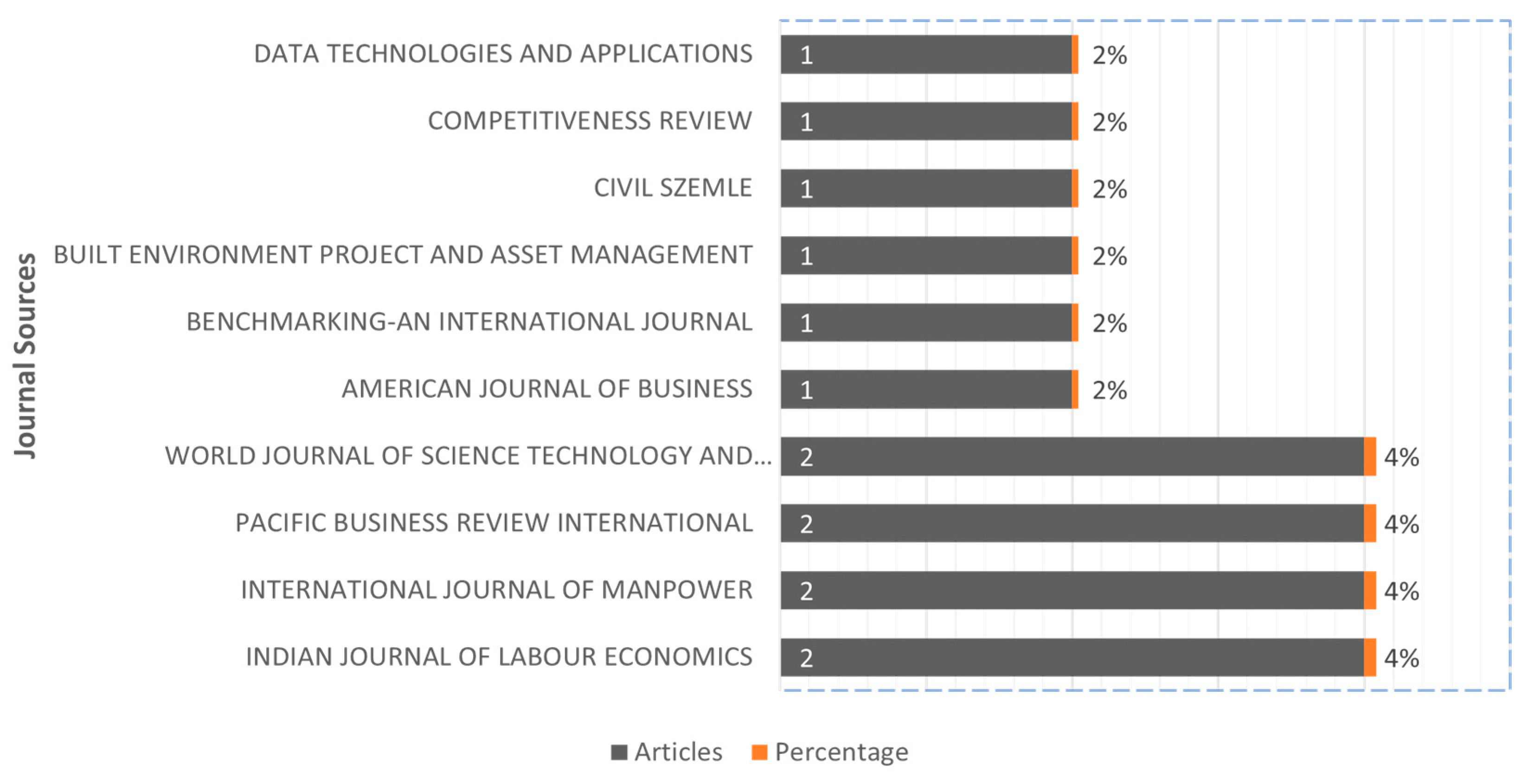

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of Systematic Review

4.2. Findings and Discussion

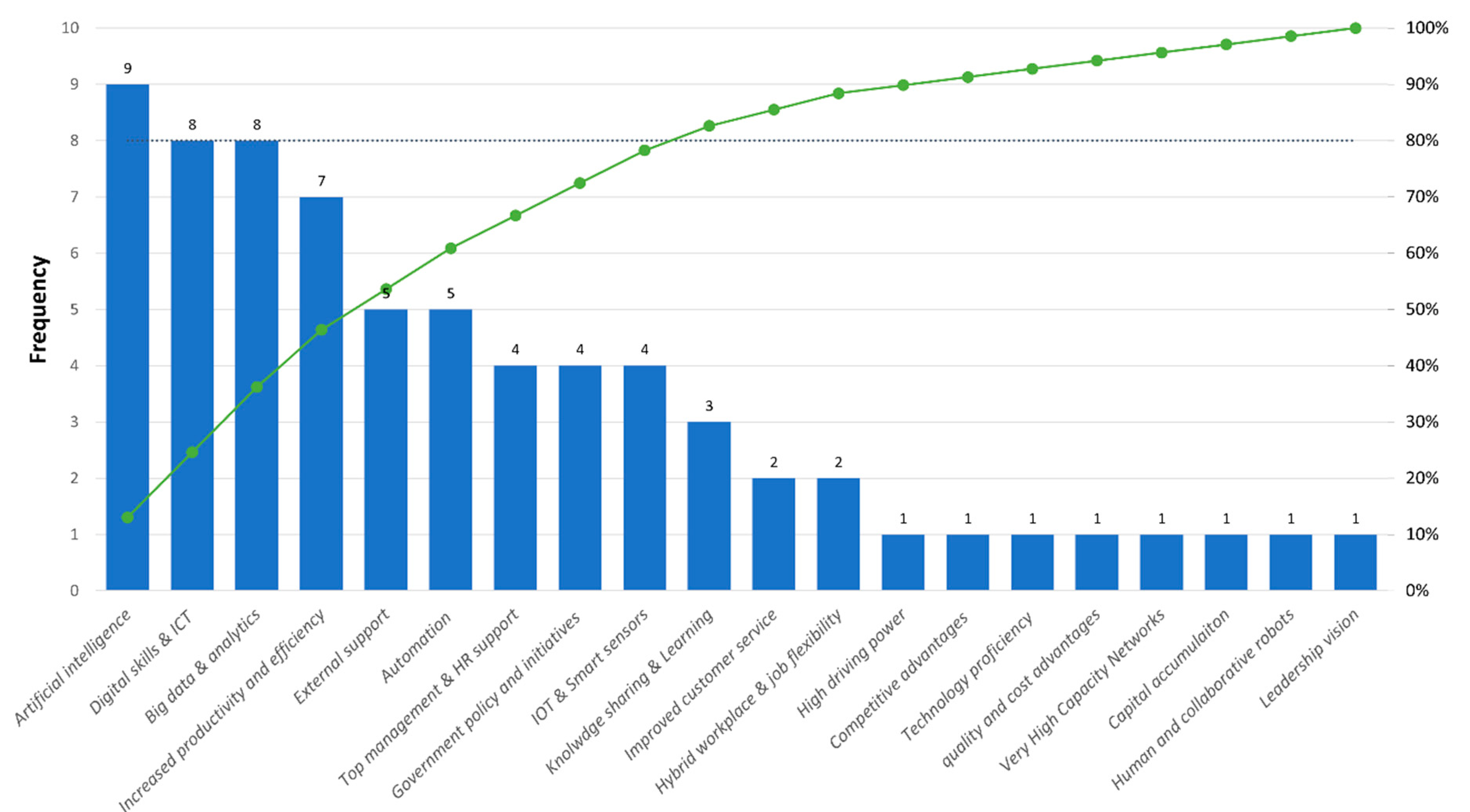

- RQ1: What are the key driving factors contributing to the success of Industry 4.0 technology implementation in South Asia?

- RQ2: What challenges exist regarding the adoption of I4.0 technologies in the region, and how do they impact the labor market and workforce skills?

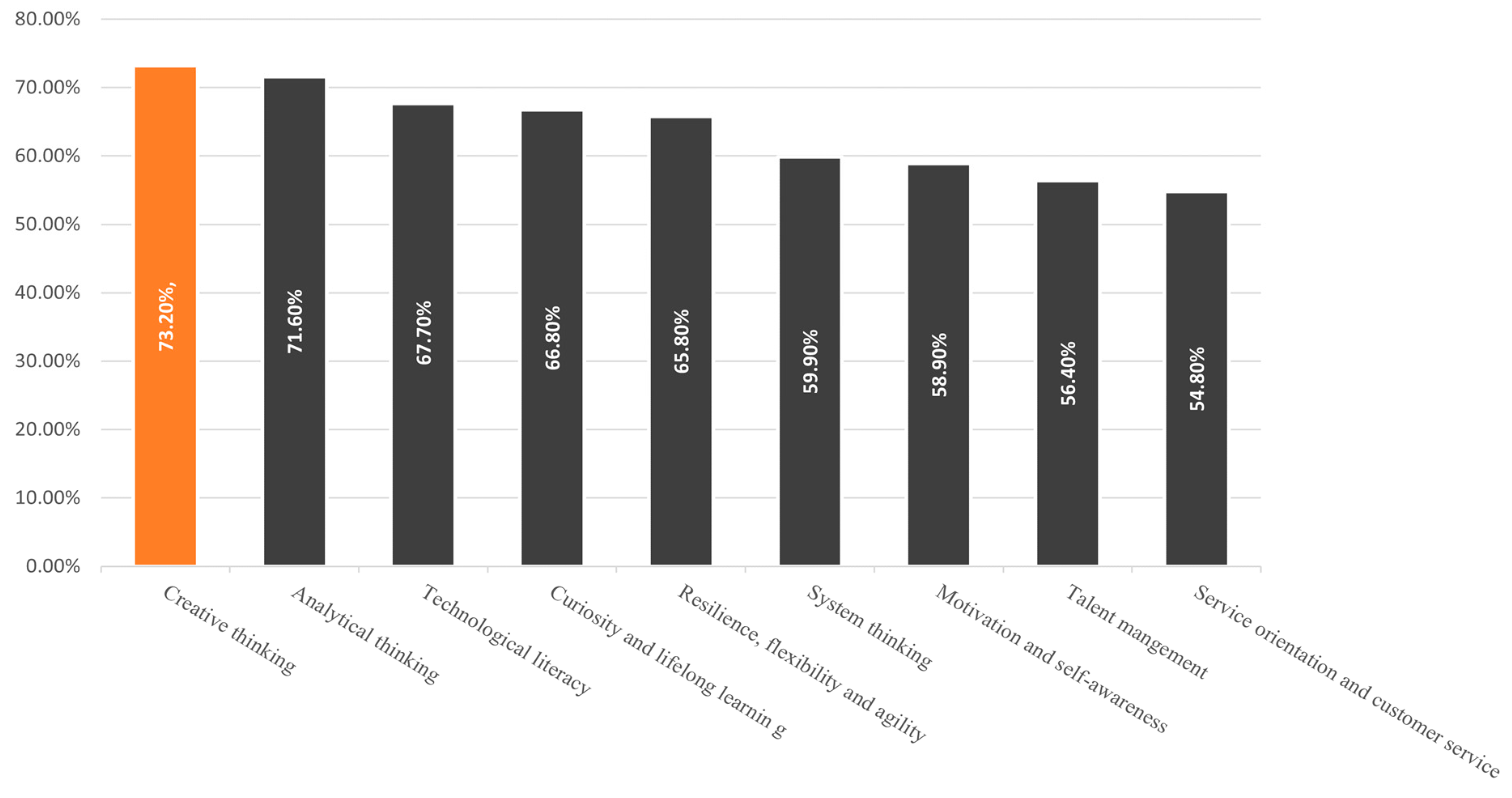

- RQ3: What are the key skill requirements and gaps resulting from the integration of I4.0 technologies?

4.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

6. Limitation and Future Research Agenda

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abuzaid, Mohamed M., Wiam Elshami, Jonathan McConnell, and H. O. Tekin. 2021. An Extensive Survey of Radiographers from the Middle East and India on Artificial Intelligence Integration in Radiology Practice. Health and Technology 11: 1045–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, Daron, and Pascual Restrepo. 2020. Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets. Journal of Political Economy 128: 2188–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, A. H. M., A. M. Rahmat, N. M. Mohtar, and N. Anuar. 2021. Industry 4.0 Critical Skills and Career Readiness of ASEAN TVET Tertiary Students in Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1793: 12004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Shafiqul, and Pavitra Dhamija. 2022. Human Resource Development 4.0 (HRD 4.0) in the Apparel Industry of Bangladesh: A Theoretical Framework and Future Research Directions. International Journal of Manpower 43: 263–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhloul, Abdelkarim, and Eva Kiss. 2022. Industry 4.0 as a Challenge for the Skills and Competencies of the Labor Force: A Bibliometric Review and a Survey. Sci 4: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Shahbaz, and Yongping Xie. 2021. The Impact of Industry 4.0 on Organizational Performance: The Case of Pakistan’s Retail Industry. European Journal of Management Studies 26: 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, Cristiana Renno D’Oliveira, and Claudio Reis Goncalo. 2021. Digital Transformation by Enabling Strategic Capabilities in the Context of ‘BRICS’. Rege-Revista de Gestao 28: 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuşlu, Merve Doğruel, and Seniye Ümit Frat. 2019. Clustering Analysis Application on Industry 4.0-Driven Global Indexes. Procedia Computer Science 158: 145–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artifice, Andreia, Fernando Luis-Ferreira, João Sarraipa, and Ricardo Jardim-Goncalves. 2019. Computational Model for Knowledge Transfer Skills in Industry 4.0 in an Enhanced and Effective Way. Paper presented at ASME 2019 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. Volume 2B: Advanced Manufacturing, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, November 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. 2021. Reaping the Benefits of Industry 4.0 through Skills Development in High-Growth Industries in Southeast Asia. Metro Manila: ADB Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, Kudrat-E-Khuda. 2021. Artificial Intelligence in Bangladesh, Its Applications in Different Sectors and Relevant Challenges for the Government: An Analysis. International Journal of Public Law and Policy 7: 319–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, Shweta, Ruchi Garg, and Monika Sethi. 2018. Total Quality Management: A Critical Literature Review Using Pareto Analysis. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 67: 128–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliester, Thereza, and Adam Elsheikhi. 2018. The Future of Work: A Literature Review. ILO Research Department Working Paper 29: 1–54. Available online: https://englishbulletin.adapt.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/wcms_625866.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Battista, Attilio Di, Sam Grayling, and Else Hasselaar. 2023. Future of Jobs Report 2023. Geneva: World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2023.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Behl, Abhishek, Meena Chavan, Kokli Jain, Isha Sharma, Vijay Edward Pereira, and Justin Zuopeng Zhang. 2022. The Role of Organizational Culture and Voluntariness in the Adoption of Artificial Intelligence for Disaster Relief Operations. International Journal of Manpower 43: 569–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasin, Narinder Kumar, and Anupama Rajesh. 2022. The Role of Emerging Banking Technologies for Risk Management and Mitigation to Reduce Non-Performing Assets and Bank Frauds in the Indian Banking System. International Journal of E-Collaboration 18: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, Sanjay, Kirankumar S. Momaya, and K. C. Iyer. 2021. Bridging the Gaps for Business Growth among Indian Construction Companies. Built Environment Project and Asset Management 11: 231–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, Sujatra, and Arup Mitra. 2020. Fourth Industrial Revolution and India’s ‘Employment Problem’. International Journal of Social Economics 47: 851–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, Som Sekhar, and Srikant Nair. 2019. Explicating the Future of Work: Perspectives from India. Journal of Management Development 38: 175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, Abul Bashar, Md Jafor Ali, Norhayah Zulkifli, and Mokana Muthu Kumarasamy. 2020. Industry 4.0: Challenges, Opportunities, and Strategic Solutions for Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management Future 4: 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkle, Caroline, David A Pendlebury, Joshua Schnell, and Jonathan Adams. 2020. Web of Science as a Data Source for Research on Scientific and Scholarly Activity. Quantitative Science Studies 1: 363–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishwakarma, Jham Kumar, and Zongshan Hu. 2022. Problems and Prospects for the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). Politics & Policy 50: 154–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolbot, Victor, Ketki Kulkarni, Päivi Brunou, Osiris Valdez Banda, and Mashrura Musharraf. 2022. Developments and Research Directions in Maritime Cybersecurity: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. International Journal of Critical Infrastructure Protection 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongomin, Ocident, Gilbert Gilibrays Ocen, Eric Oyondi Nganyi, Alex Musinguzi, and Timothy Omara. 2020. Exponential Disruptive Technologies and the Required Skills of Industry 4.0. Journal of Engineering 2020: 4280156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brás, Gonçalo Rodrigues. 2023. Pillars of the Global Innovation Index by Income Level of Economies: Longitudinal Data (2011–2022) for Researchers’ Use. Data in Brief 46: 108818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigitta, C. 2022. The Past and Present of Indian Civil Society. Civil Szemle 19: 81–108. [Google Scholar]

- Cannavacciuolo, Lorella, Giovanna Ferraro, Cristina Ponsiglione, Simonetta Primario, and Ivana Quinto. 2023. Technological Innovation-Enabling Industry 4.0 Paradigm: A Systematic Literature Review. Technovation 124: 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Weiru, Wu He, Jiayue Shen, Xin Tian, and Xianping Wang. 2023. Systematic Analysis of Artificial Intelligence in the Era of Industry 4.0. Journal of Management Analytics 10: 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenoy, Dilip, Shobha Mishra Ghosh, and Shiv Kumar Shukla. 2019. Skill Development for Accelerating the Manufacturing Sector: The Role of ‘new-Age’ Skills for ‘Make in India’. International Journal of Training Research 17: 112–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culot, Giovanna, Guido Nassimbeni, Guido Orzes, and Marco Sartor. 2020. Behind the Definition of Industry 4.0: Analysis and Open Questions. International Journal of Production Economics 226: 107617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Ron. 2015. Industry 4.0 Digitalization for Productivity and Growth. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1335939/industry-40/1942749/ (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Devkota, Niranjan, Sharad Rajbhandari, Udaya Raj Poudel, and Seeprata Parajuli. 2022. Obstacles of Implementing Industry 4.0 in Nepalese Industries and Way-Forward. International Journal of Finance Research 2: 286–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dregger, Johannes, Jonathan Niehaus, Peter Ittermann, Hartmut Hirsch-Kreinsen, and Michael Ten Hompel. 2016. The Digitization of Manufacturing and Its Societal Challenges: A Framework for the Future of Industrial Labor. Paper presented at the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Ethics in Engineering, Science and Technology (ETHICS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, May 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- D’souza, Brayal, Shreyas Suresh Rao, Chepudira Ganapathy Muthana, Reshmi Bhageerathy, Nikitha Apuri, Varalakshmi Chandrasekaran, Deena Prabhavathi, and Sapna Renukaradhya. 2021. ROTA: A System for Automated Scheduling of Nursing Duties in a Tertiary Teaching Hospital in South India. Health Informatics Journal 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Sunasir. 2017. Creating in the Crucibles of Nature’s Fury: Associational Diversity and Local Social Entrepreneurship after Natural Disasters in California, 1991–2010. Administrative Science Quarterly 62: 443–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echchakoui, Saïd, and Noureddine Barka. 2020. Industry 4.0 and Its Impact in Plastics Industry: A Literature Review. Journal of Industrial Information Integration 20: 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, Shah Md Azimul. 2021. Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Labor Market in Bangladesh. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erboz, Gizem. 2017. How to Define Industry4.0: The Main Pillars of Industry 4.0. In Managerial Trends in the Development of Enterprises in Globalization Era. Edited by I. Kosiciarova and Z. Kadekova. 761-67. Tr A Hlinku2, Nitra, 94976. Slovakia: Slovak Univ Agriculture Nitra. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326557388_How_To_Define_Industry_40_Main_Pillars_Of_Industry_40 (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Freund, Lucas, and Salah Al-Majeed. 2021. Managing Industry 4.0 Integration—The Industry 4.0 Knowledge & Framework. Logforum 17: 569–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gadre, Monika, and Aruna Deoskar. 2021. Interpretations and Impact of New Education Policy 2020 on Indian Higher Education for Industry 4.0. Pacific Business Review International 14: 93–105. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355668078_Interpretations_and_Impact_of_New_Education_Policy_2020_on_Indian_Higher#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Ghislieri, Chiara, Monica Molino, and Claudio G. Cortese. 2018. Work and Organizational Psychology Looks at the Fourth Industrial Revolution: How to Support Workers and Organizations? Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, Morteza. 2020. Industry 4.0, Digitization, and Opportunities for Sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 252: 119869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, Mohit, and Yash Daultani. 2022. Make-in-India and Industry 4.0: Technology Readiness of Select Firms, Barriers and Socio-Technical Implications. TQM Journal 34: 1485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, Michael, and Neal R Haddaway. 2020. Which Academic Search Systems Are Suitable for Systematic Reviews or Meta-analyses? Evaluating Retrieval Qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 Other Resources. Research Synthesis Methods 11: 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Anita, and Suparna Karmakar. 2021. Automation, AI and the Future of Work in India. Employee Relations 43: 1327–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Joshua D., Carmen E. Quatman, Maurice M Manring, Robert A Siston, and David C Flanigan. 2014. How to Write a Systematic Review. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 42: 2761–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Md. Zahid, Avijit Mallik, and Jia-Chi Tsou. 2021. Learning Method Design for Engineering Students to Be Prepared for Industry 4.0: A Kaizen Approach. Higher Education Skills and Work-Based Learning 11: 182–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Jonathan, Andrew J Thomas, R. K. Mason-Jones, and Sherien El-Kateb. 2018. The Implementation of a Lean Six Sigma Framework to Enhance Operational Performance in an MRO Facility. Production & Manufacturing Research 6: 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, Nandeesh V., Amiya Kumar Mohapatra, and Anil Subbarao Paila. 2021. A Study on Digital Learning, Learning and Development Interventions and Learnability of Working Executives in Corporates. American Journal of Business 36: 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hizam-Hanafiah, Mohd, Mansoor Ahmed Soomro, and Nor Liza Abdullah. 2020. Industry 4.0 Readiness Models: A Systematic Literature Review of Model Dimensions. Information 11: 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, Jacob Rubæk, and Edward Lorenz. 2022. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Skills at Work in Denmark. New Technology, Work and Employment 37: 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Imranul, and Md. Shahinuzzaman. 2021. Task Performance and Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems in the Garment Industry of Bangladesh. International Journal of Workplace Health Management 14: 369–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, Dóra, and Roland Zs Szabó. 2019. Driving Forces and Barriers of Industry 4.0: Do Multinational and Small and Medium-Sized Companies Have Equal Opportunities? Technological Forecasting and Social Change 146: 119–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Sourav, Sanjida Hassan, and Rubayet Karim. 2023. Assessment of Critical Barriers to Industry 4.0 Adoption in Manufacturing Industries of Bangladesh: An ISM-Based Study. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management 20: 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husin, Mohd Heikal, Noor Farizah Ibrahim, Nor Athiyah Abdullah, Sharifah Mashita Syed-Mohamad, Nur Hana Samsudin, and Leonard Tan. 2022. The Impact of Industrial Revolution 4.0 and the Future of the Workforce: A Study on Malaysian IT Professionals. Social Science Computer Review 41: 1671–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, Muhammad, Waseem ul Hameed, and Adnan ul Haque. 2018. Influence of Industry 4.0 on the Production and Service Sectors in Pakistan: Evidence from Textile and Logistics Industries. Social Sciences 7: 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrana, Syed Muhammad, Syed Mumtaz Ali Kazmib, Farva Jawadc, and Iqra Ghousd. 2021. The Impact of Human Capital on Innovation: Empirical Evidence from South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change 15. Available online: https://www.ijicc.net/images/Vol_15/Iss_8/15919_Imran_2021_E_R.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- International Monetary Fund. 2023. World Economic Outlook: Navigating Global Divergences. Washington, DC. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2023/10/10/world-economic-outlook-october-2023 (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Iqbal, Mohammed Masum, K M Anwarul Islam, Nurul Mohammad Zayed, Tahrima Haque Beg, and Shahiduzzaman Khan Shahi. 2021. Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Economy on Industrial Revolution 4: Evidence from Bangladesh. American Finance & Banking Review 6: 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, Iram. 2023. The Impact of Industry 4.0 on Employability and the Skills Required in India. Global Economics Science 4: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.Y.M. Atiquil, Khurshid Ahmad, Muhammad Rafi, and Zheng Jian Ming. 2021. Performance-Based Evaluation of Academic Libraries in the Big Data Era. Journal of Information Science 47: 458–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Tarikul, Subhas Chandra Mukhopadhyay, and Nagender Kumar Suryadevara. 2017. Smart Sensors and Internet of Things: A Postgraduate Paper. IEEE Sensors Journal 17: 577–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, Abhijitkumar Anandrao, Deepali Aanandrao Suryawanshi, Sandeep Sureshrao Ahankari, and Sanjay Bhaskar Zope. 2022. A Technology-Enabled Assessment and Attainment of Desirable Competencies. Education for Chemical Engineers 39: 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Vineet, and Puneeta Ajmera. 2021. Modelling the Enablers of Industry 4.0 in the Indian Manufacturing Industry. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 70: 1233–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Vineet, and Puneeta Ajmera. 2022. Modelling the Barriers of Industry 4.0 in India Using Fuzzy TISM. International Journal of Business Performance Management 23: 347–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Vineet, Puneeta Ajmera, and Joao Paulo Davim. 2022. SWOT Analysis of Industry 4.0 Variables Using AHP Methodology and Structural Equation Modelling. Benchmarking-An International Journal 29: 2147–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, Akanksha, C. Joe Arun, and Arup Varma. 2022. Rebooting Employees: Upskilling for Artificial Intelligence in Multinational Corporations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 33: 1179–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, Sadia. 2022. Evolving Newsrooms and the Second Level of Digital Divide: Implications for Journalistic Practice in Pakistan. Journalism Practice 17: 1864–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, Pratiksha. 2021. Digitization and Industry 4.0 Practices: An Exploratory Study on SMEs in India. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jony, Sheikh Saifur Rahman, Tsuyoshi Kano, Ryotaro Hayashi, Norihiko Matsuda, and M. Sohel Rahman. 2022. An Exploratory Study of Online Job Portal Data of the ICT Sector in Bangladesh: Analysis, Recommendations and Preliminary Implications for ICT Curriculum Reform. Education Sciences 12: 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Seema. 2021. Rising Importance of Remote Learning in India in the Wake of COVID-19: Issues, Challenges and Way Forward. World Journal of Science Technology and Sustainable Development 18: 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, Bzhwen A., Ole Broberg, and Carolina Souza da Conceição. 2019. Current Research and Future Perspectives on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Industry 4.0. Computers and Industrial Engineering 137: 106004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagermann, Henning, Wolf-Dieter Lukas, and Wolfgang Wahlster. 2011. Industrie 4.0: Mit Dem Internet Der Dinge Auf Dem Weg Zur 4. Industriellen Revolution. VDI Nachrichten 13: 2–3. Available online: https://www-live.dfki.de/fileadmin/user_upload/DFKI/Medien/News_Media/Presse/Presse-Highlights/vdinach2011a13-ind4.0-Internet-Dinge.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Kagermann, Henning, Wolfgang Wahlster, and Johannes Helbig. 2013. Recommendations for Implementing the Strategic Initiative Industrie 4.0: Final Report of the Industrie 4.0 Working Group. Berlin, Germany: Available online: https://www.din.de/resource/blob/76902/e8cac883f42bf28536e7e8165993f1fd/recommendations-for-implementing-industry-4-0-data.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Kanji, Repaul, and Rajat Agrawal. 2020. Exploring the Use of Corporate Social Responsibility in Building Disaster Resilience through Sustainable Development in India: An Interpretive Structural Modelling Approach. Progress in Disaster Science 6: 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, Sudatta, Arpan K. Kar, and M. P. Gupta. 2021. Industrial Internet of Things and Emerging Digital Technologies-Modeling Professionals’ Learning Behavior. IEEE Access 9: 30017–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, Samrakshya, and Bonaventura Hadikusumo. 2023. Machine Learning for the Identification of Competent Project Managers for Construction Projects in Nepal. Construction Innovation-England 23: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppusami, Gandhinathan, and R. Gandhinathan. 2006. Pareto Analysis of Critical Success Factors of Total Quality Management: A Literature Review and Analysis. The TQM Magazine 18: 372–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katekar, Vikrant, and Sandip S Deshmukh. 2021. En Route for the Accomplishment of SDG-7 in South Asian Countries: A Retrospective Study. Strategic Planning for Energy and the Environment 40: 195–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattimani, Shivaputrappa Fakkirappa, and Ramesh R. Naik. 2013. Evaluation of Librarianship and ICT Skills of Library and Information Professionals Working in the Engineering College Libraries in Karnataka, India: A Survey. Program-Electronic Library and Information Systems 47: 344–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, Cristina Orsolin, Marco Antônio Viana Borges, and José Antônio do Vale Antunes. 2022. Industry 4.0: What Makes It a Revolution? A Historical Framework to Understand the Phenomenon. Technology in Society 70: 102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalikova, Petra, Petr Polak, and Roman Rakowski. 2020. The Challenges of Defining the Term “Industry 4.0”. Society 57: 631–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Surendra. 2019. Artificial Intelligence Divulges Effective Tactics of Top Management Institutes of India. Benchmarking-An International Journal 26: 2188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Marguerita, and Anne Saint-Martin. 2021. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Labour Market: What Do We Know So Far? OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 256. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Wai Yie, Joon Huang Chuah, and Tee Boon Tuan. 2020. The Nine Pillars of Technologies for Industry 4.0. Selangor: Institution of Engineering and Technology, p. 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Ling. 2022. Reskilling and Upskilling the Future-Ready Workforce for Industry 4.0 and beyond. Information Systems Frontiers, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, Meena, Sutee Wangtueai, Mohammed Ali Sharafuddin, and Thanapong Chaichana. 2022. The Precipitative Effects of Pandemic on Open Innovation of SMEs: A Scientometrics and Systematic Review of Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 8: 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisiri, Whisper, Hasan Darwish, and Liezl van Dyk. 2019. An Investigation of Industry 4.0 Skills Requirements. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering 30: 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manda, More Ickson, and Soumaya Ben Dhaou. 2019. Responding to the Challenges and Opportunities in the 4th Industrial Revolution in Developing Countries. Paper presented at the 12th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Melbourne, Australia, April 3–5; pp. 244–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, Saman, Ali Sher, Azhar Abbas, Abdul Ghafoor, and Guanghua H. Lin. 2022. Empowering Shepreneurs to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals: Exploring the Impact of Interest-Free Start-up Credit, Skill Development and ICTs Use on Entrepreneurial Drive. Sustainable Development 30: 1235–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, Balwant Singh, and Ishwar Chandra Awasthi. 2019. Industry 4.0 and Future of Work in India. FIIB Business Review 8: 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezina, T. V., A. V. Zozulya, P. V. Zozulya, T. F. Chernova, and A. V. Pletnyova. 2022. Impact of Industry 4.0 on the Economy and Production. Vestnik Universiteta 2: 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G Altman, and PRISMA Group*. 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 151: 264–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, Muhammad, Md. Samim Al Azad, Selim Ahmed, Slimane Ed-Dafali, and Mohammad Nurul Hasan Reza. 2022. Evolution of Industry 4.0 and Its Implications for International Business. In Global Trade in the Emerging Business Environment. London: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, Arpita, and Divya Satija. 2020. Regional Cooperation in Industrial Revolution 4.0 and South Asia: Opportunities, Challenges and Way Forward. South Asia Economic Journal 21: 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizami, Nausheen, Tulika Tripathi, and Meha Mohan. 2022. Transforming Skill Gap Crisis into Opportunity for Upskilling in India’s IT-BPM Sector. Indian Journal of Labour Economics 65: 845–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudurupati, Sai Sudhakar, Pawan Budhwar, Raja Phani Pappu, Soumyadeb Chowdhury, Mukesh Kondala, Ayon Chakraborty, and Sadhan Kumar Ghosh. 2022. Transforming Sustainability of Indian Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises through Circular Economy Adoption. Journal of Business Research 149: 250–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterreich, Thuy Duong, and Frank Teuteberg. 2016. Understanding the Implications of Digitisation and Automation in the Context of Industry 4.0: A Triangulation Approach and Elements of a Research Agenda for the Construction Industry. Computers in Industry 83: 121–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, and Sue E. Brennan. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. International Journal of Surgery 88: 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park-Poaps, Haesun, Md. Sadaqul Bari, and Zafar Waziha Sarker. 2021. Bangladeshi Clothing Manufacturers’ Technology Adoption in the Global Free Trade Environment. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 25: 354–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, Saurabh, and Bhawna Sharma. 2022. Artificial Intelligence for Improving Employee Engagement in South Asian Banking Industry: A Systematic Literature Review. NeuroQuantology 20: 17. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Gustavo Bernardi, Adriana de Paula Lacerda Santos, and Marcelo Gechele Cleto. 2018. Industry 4.0: Glitter or Gold? A Systematic Review. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management 15: 247–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Perales, David, Faustino Alarcon Valero, and Andres Boza Garcia. 2018. Industry 4.0: A Classification Scheme. In Closing the Gap between Practice and Research in Industrial Engineering. Edited by E. Viles, M. Ormazabal and A. Lleo. Lecture Notes in Management and Industrial Engineering. Cham: Springer International Publishing Ag, pp. 343–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phethean, Christopher, Elena Simperl, Thanassis Tiropanis, Ramine Tinati, and Wendy Hall. 2016. The Role of Data Science in Web Science. IEEE Intelligent Systems 31: 102–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccarozzi, Michela, Barbara Aquilani, and Corrado Gatti. 2018. Industry 4.0 in Management Studies: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 10: 3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Alex, and Eivind Berge. 2018. How to Do a Systematic Review. International Journal of Stroke 13: 138–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, Raminta. 2021. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 9: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puriwat, Wilert, and Suchart Tripopsakul. 2020. Preparing for Industry 4.0—Will Youths Have Enough Essential Skills? An Evidence from Thailand. International Journal of Instruction 13: 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, Fakhreddin F, Pejvak Oghazi, Maximilian Palmie, Koteshwar Chirumalla, Natallia Pashkevich, Pankaj C Patel, and Setayesh Sattari. 2022. Industry 4.0 and Supply Chain Performance: A Systematic Literature of the Benefits, Challenges, and Critical Success Factors of 11 Technologies. Industrial Marketing Management 105: 268–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Noorul Shaiful Fitri Abdul, Abdelsalam Adam Hamid, Taih-Cherng Lirn, Khalid Al Kalbani, and Bekir Sahin. 2022. The Adoption of Industry 4.0 Practices by the Logistics Industry: A Systematic Review of the Gulf Region. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain 5: 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, Alok, Gourav Dwivedi, Ankit Sharma, Ana Beatriz de Sousa Jabbour, and Sonu Rajak. 2020. Barriers to the Adoption of Industry 4.0 Technologies in the Manufacturing Sector: An Inter-Country Comparative Perspective. International Journal of Production Economics 224: 107546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamanickam, Srinivasan. 2016. Exploring Landscapes in Regional Convergence. In Handbook of Research on Global Indicators of Economic and Political Convergence. Pennsylvania: IGI Global, pp. 474–510. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, Narasimha D. 2020. Future of Work and Emerging Challenges to the Capabilities of the Indian Workforce. Indian Journal of Labour Economics 63: 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Hafiz Mudassir, Au Yong Hui Nee, Choong Yuen Onn, and Mobashar Rehman. 2021. Barriers to Adoption of Industry 4.0 in Manufacturing Sector. Paper presented at the 2021 International Conference on Computer & Information Sciences (ICCOINS), Kuching, Malaysia, July 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rethlefsen, Melissa L, Shona Kirtley, Siw Waffenschmidt, Ana Patricia Ayala, David Moher, Matthew J Page, and Jonathan B Koffel. 2021. PRISMA-S: An Extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews 10: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Gonçalo, Bruno Carvalho, Andreia Reigoto, Ana Elias, Pedro Batista, Sandra Jardim, and Nuno Madeira. 2017. Training at Instituto Politécnico de Tomar: Skill Alignment to Respond to the Industry 4.0 Challenges. Superavit 2: 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Leonardo, Fabian Quint, Dominic Gorecky, David Romero, and Héctor R Siller. 2015. Developing a Mixed Reality Assistance System Based on Projection Mapping Technology for Manual Operations at Assembly Workstations. Procedia Computer Science 75: 327–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Philip, and Kasia Maynard. 2021. Towards a 4th Industrial Revolution. Intelligent Buildings International 13: 159–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, Anish, Vinay Kumar Sharma, and Lakhwinderpal Singh. 2022. Industry 4.0 and Indian SMEs: A Study of Espousal Challenges Using AHP Technique. Paper presented at the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, December 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sallati, Carolina, Júlia de Andrade Bertazzi, and Klaus Schützer. 2019. Professional Skills in the Product Development Process: The Contribution of Learning Environments to Professional Skills in the Industry 4.0 Scenario. Procedia CIRP 84: 203–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniuk, Sebastian, Dagmar Caganova, and Anna Saniuk. 2021. Knowledge and Skills of Industrial Employees and Managerial Staff for the Industry 4.0 Implementation. Mobile Networks and Applications 28: 220–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savytska, O., and V. Salabai. 2021. Digital Transformations in The Conditions of Industry 4.0 Development. Financial and Credit Activity-Problems of Theory and Practice 3: 420–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayem, Ahmed, Pronob Kumar Biswas, Mohammad Muhshin Aziz Khan, Luca Romoli, and Michela Dalle Mura. 2022. Critical Barriers to Industry 4.0 Adoption in Manufacturing Organizations and Their Mitigation Strategies. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 6: 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöning, Harald. 2018. Industry 4.0. IT—Information Technology 60: 121–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, Klaus. 2017. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Geneva: World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Arun Kumar, Rakesh Bhandari, Camelia Pinca-Bretotean, Chaitanya Sharma, Shri Krishna Dhakad, and Ankita Mathur. 2021. A Study of Trends and Industrial Prospects of Industry 4.0. Materials Today: Proceedings 47: 2364–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Manu, Sunil Luthra, Sudhanshu Joshi, and Anil Kumar. 2022. Implementing Challenges of Artificial Intelligence: Evidence from Public Manufacturing Sector of an Emerging Economy. Government Information Quarterly 39: 101624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreenath, A., and S. Manjunath. 2021. Impact of Learning Virtual Reality on Enhancing Employability of Indian Engineering Graduates. Pacific Business Review International 13: 80–88. Available online: https://archives.palarch.nl/index.php/jae/article/view/9680 (accessed on 19 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Singhal, Neeraj. 2021. An Empirical Investigation of Industry 4.0 Preparedness in India. Vision-The Journal of Business Perspective 25: 300–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolka, David, and Zuzana Papulova. 2023. Industry 4.0 Adoption—A Case of Manufacturing Companies. In Human Interaction & Emerging Technologies (IHIET 2023): Artificial Intelligence & Future Applications. New York: AHFE Open Access, vol. 111, pp. 934–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoettl, Georg, and Vidmantas Tūtlys. 2020. Education and Training for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Jurnal Pendidikan Teknologi Dan Kejuruan 26: 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, Sunil Kumar. 2018. Artificial Intelligence: Way Forward for India. JISTEM-Journal of Information Systems and Technology Management 15: e201815004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Shun-Feng, Imre J Rudas, Jacek M Zurada, Meng Joo Er, Jyh-Horng Chou, and Daeil Kwon. 2017. Industry 4.0: A Special Section in IEEE Access. IEEE Access 5: 12257–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Suha, Sayma Alam, and Tahsina Farah Sanam. 2022. Challenges and Prospects of Adopting Industry 4.0 and Assessing the Role of Intelligent Robotics. Paper presented at the 2022 IEEE World Conference on Applied Intelligence and Computing (AIC), Sonbhadra, India, June 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Szabó-Szentgróti, Gábor, Bence Végvári, and József Varga. 2021. Impact of Industry 4.0 and Digitization on Labor Market for 2030-Verification of Keynes’ Prediction. Sustainability 13: 7703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, Shu, Lee Te Chuan, A Aziati, and Ahmad Nur Aizat Ahmad. 2018. An Overview of Industry 4.0: Definition, Components, and Government Initiatives. Journal of Advanced Research in Dynamical and Control Systems 10: 14. Available online: https://simbotix.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/I4.0-Defintiions.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2023).

- Tiwari, Saurabh. 2021. Supply Chain Integration and Industry 4.0: A Systematic Literature. Benchmarking-An International Journal 28: 990–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschang, Feichin Ted, and Esteve Almirall. 2021. Artificial Intelligence as Augmenting Automation: Implications for Employment. Academy of Management Perspectives 35: 642–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushar, Saifur Rahman, Md Fahim Bin Alam, Sadid Md Zaman, Jose Arturo Garza-Reyes, A. B. M. Mainul Bari, and Chitra Lekha Karmaker. 2023. Analysis of the Factors Influencing the Stability of Stored Grains: Implications for Agricultural Sustainability and Food Security. Sustainable Operations and Computers 4: 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, Saurabh, Prashant Ambad, and Santosh Bhosle. 2018. Industry 4.0—A Glimpse. Procedia Manufacturing 20: 233–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos Oliveira, Rita. 2021. Social Innovation for a Just Sustainable Development: Integrating the Wellbeing of Future People. Sustainability 13: 9013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, Surabhi, and Vibhav Singh. 2022. The Employees Intention to Work in Artificial Intelligence-Based Hybrid Environments. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 71: 3266–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuksanović Herceg, Iva, Vukašin Kuč, Veljko M Mijušković, and Tomislav Herceg. 2020. Challenges and Driving Forces for Industry 4.0 Implementation. Sustainability 12: 4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasekara, Sachini, Zhenyuan Lu, Burcu Ozek, Jacqueline Isaacs, and Sagar Kamarthi. 2022. Trends in Adopting Industry 4.0 for Asset Life Cycle Management for Sustainability: A Keyword Co-Occurrence Network Review and Analysis. Sustainability 14: 12233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortmann, Felix, and Kristina Flüchter. 2015. Internet of Things: Technology and Value Added. Business & Information Systems Engineering 57: 221–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woschank, Manuel, Elena Del Río, Helmut E. Zsifkovits, and Patrick Dallasega. 2020. Comparison of Industry 4.0 Requirements between Central-European and South-East-Asian Enterprises. Paper presented at the 5th NA International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Detroit, MI, USA, August 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, An-Chi, and Duc-Dinh Kao. 2022. Mapping the Sustainable Human-Resource Challenges in Southeast Asia’s FinTech Sector. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuni, Ibrahim Yahaya. 2022. Mapping the Barriers to Circular Economy Adoption in the Construction Industry: A Systematic Review, Pareto Analysis, and Mitigation Strategy Map. Building and Environment 223: 109453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, Akhliesh K. S. 2022. The Essential Skills and Competencies of LIS Professionals in the Digital Age: Alumni Perspectives Survey. Global Knowledge Memory and Communication 71: 837–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, Seda, and Seda H. Bostanci. 2021. The Efficiency of E-Government Portal Management from a Citizen Perspective: Evidences from Turkey. World Journal of Science Technology and Sustainable Development 18: 259–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Keliang, Taigang Liu, and Lifeng Zhou. 2015. Industry 4.0: Towards Future Industrial Opportunities and Challenges. Proceedings of the 2015 12th International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (FSKD), Zhangjiajie, China, August 15–17; pp. 2147–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Driving Success Factors | Challenges/Obstacles | Skills Requirement and Gaps | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased efficiency, productivity improved customer service and cost savings, automation, quality, and cost advantages | Investment cost, skill gap, reluctant to implement industry 4.0, lack of funds, uncertainties of the investment, data security and lack of qualified employees, employee resistance | Analytical skills, skills in data security, and data management | (Hoque and Shahinuzzaman 2021; Singhal 2021) |

| Top management support, high driving power, financial support | Employee resistance, insufficient maintenance of support systems | Specialized training and skills | (Jain and Ajmera 2022, 2021) |

| Flexibility, accuracy, and speed to business operations. | Technical and interpersonal skills, conceptual skills, social skills, managerial skills | (Joshi 2021) | |

| Competitive advantages | Resistance to change, barriers of adoptions, coordination and collaboration, government initiatives and policy, customer pressure, environmental regulation | Analysis, skills and expertise, digital transformation | (Goswami and Daultani 2022; Nudurupati et al. 2022; Chenoy et al. 2019) |

| Holistic development, lifelong learning, and outcome-based education | Lacks the availability of basic infrastructure | Research skills, computing skills, data management and soft skills | (Gadre and Deoskar 2021; Yadav 2022) |

| Technology proficiency | Training retraining of people | Technical skills, entrepreneurial and soft skills, communication, and interpersonal skills | (Mehta and Awasthi 2019; Jain et al. 2022; Jadhav et al. 2022) |

| External support, investments in technologies, transformation, knowledge sharing | Readiness in operations technology, international finance, international experience, and international network | Leadership skills, adaptability skill, team development | (Dutta 2017; Karki and Hadikusumo 2023; Chen et al. 2023) |

| Networking and automation, government policies for bridging skill gaps, forging partnerships and policies | Digital learning, crisis of human resources, learning strategy, professional skills | Virtual reality, non-cognitive skills, | (Shreenath and Manjunath 2021; Hiremath et al. 2021; Joshi 2021; Kumar 2019; Hasan et al. 2021; D’souza et al. 2021) |

| Hybrid workplaces, industry 4.0, humans and collaborative robots, leadership vision, | Institutional pressure on workforce skill, capital accumulation, cost of employment | Creativity, human resources, digital transformation skill, technical and managerial skills | (Verma and Singh 2022; Bhattacharyya and Mitra 2020; Vasconcellos Oliveira 2021; Alam and Dhamija 2022; Nizami et al. 2022) |

| Robotics, artificial intelligence, internet of things, automation, very high-capacity networks, big data analytics, Internet of Things, ICT, learning, smart sensors | Adaptability of workers and reforms in education sector, public investment and public provision, job security | Digital transformation and entrepreneurship, and sustainable knowledge management, ICT job skills, software developers, technical skill, digital skills, | (Nizami et al. 2022; Reddy 2020; Brigitta 2022; Mazhar et al. 2022; Jony et al. 2022; Hammer and Karmakar 2021; Islam et al. 2021; Islam et al. 2017; Bhasin and Rajesh 2022; Abuzaid et al. 2021; Tiwari 2021; Behl et al. 2022; Sachdeva et al. 2022; Tay et al. 2018; Kattimani and Naik 2013) |

| Personal innovativeness, leadership vision | Social influence, anxiety, long-term consequences, and job relevance, security, and access options | Communication skills, technical skills, problem-solving, relationship management skills. | (Yildirim and Bostanci 2021; Kar et al. 2021; Bhattacharya et al. 2021) |

| Job flexibility, human capital and knowledge transfer, digital transformation | Lack of autonomous system | Data analysis, complex cognitive, decision making and continuous learning skills, digital skill, technical skill | (Jaiswal et al. 2022; Bhattacharyya and Nair 2019; Jamil 2022; Park-Poaps et al. 2021; Andrade and Goncalo 2021) |

| Challenges of Industry 4.0 Technology Adoption in South Asia | Occurrences | Percentages (%) | Cumulative (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Training and development (training and retraining of people, digital learning, crisis of human resources, learning strategy, lack of professional skills, digital learning, remote learning, education reform, lack of basic infrastructures) | 9 | 27 | 27 |

| 2. | Skills and workforces (skill gap, reluctant to implement industry 4.0, institutional pressure on workforce, adaptability of workers, lack of qualified employees, employee resistance, insufficient maintenance support system) | 7 | 21 | 48 |

| 3. | Financial challenges (investment cost, lack of international supports, cost of employment, capital accumulation, lack of funds uncertainty of investment) | 6 | 18 | 66 |

| 4. | Regulatory challenges (resistance to change, co-ordination and collaboration, government initiatives and policy, environmental regulation) | 4 | 12 | 79 |

| 5. | Technology challenges (data security, lack of autonomous system, data access option, readiness to operate technologies) | 4 | 12 | 91 |

| 6. | Social and psychological challenges (social influence, anxiety, long term consequences of job loss) | 3 | 9 | 100 |

| Skills Requirements and Gaps in South Asia | Occurrences | Percentages (%) | Cumulative (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Technical and ICT (Technical Skills, Information Technology, Specialized Manufacturing Skills, Information Technology, Data Analytical Skills, Data Management Skills, Conceptual Skills) | 10 | 26 | 26 |

| 2. | Communication and Interpersonal (Social Skills, Employability and Lifelong Learning Skills, Soft Skills, Cognitive Skills, Resistance Skills, Human Resources Skills) | 6 | 26 | 52 |

| 3. | Problem-Solving and Relationship (Adaptability Skills, Problem-Solving Skills, Stakeholder/Relationship Management Skills, Professional Skills, Analytical Skills) | 5 | 19 | 91 |

| 4. | Digital (ICT Skills, Digital Skills, Digital Transformation Skills, Remote Learning Capacity) | 4 | 15 | 66 |

| 5. | Entrepreneurial and Leadership Skills (Entrepreneurial Skills, Managerial Skills, Decision-Making Skills, Leadership Skills) | 2 | 15 | 79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miah, M.T.; Erdei-Gally, S.; Dancs, A.; Fekete-Farkas, M. A Systematic Review of Industry 4.0 Technology on Workforce Employability and Skills: Driving Success Factors and Challenges in South Asia. Economies 2024, 12, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12020035

Miah MT, Erdei-Gally S, Dancs A, Fekete-Farkas M. A Systematic Review of Industry 4.0 Technology on Workforce Employability and Skills: Driving Success Factors and Challenges in South Asia. Economies. 2024; 12(2):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12020035

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiah, Md. Tota, Szilvia Erdei-Gally, Anita Dancs, and Mária Fekete-Farkas. 2024. "A Systematic Review of Industry 4.0 Technology on Workforce Employability and Skills: Driving Success Factors and Challenges in South Asia" Economies 12, no. 2: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12020035

APA StyleMiah, M. T., Erdei-Gally, S., Dancs, A., & Fekete-Farkas, M. (2024). A Systematic Review of Industry 4.0 Technology on Workforce Employability and Skills: Driving Success Factors and Challenges in South Asia. Economies, 12(2), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12020035