Abstract

Since their origins, rural development programs have considered the county level as the axis on which to implement their development strategies. Taking Tajo-Salor County (Extremadura, Spain) as a reference, this research analyzes the assessment that some of the agents directly involved in the implementation of these programs make of the suitability of the configuration of their territorial scope, as well as the achievement of their objectives. For it, the case study methodology is used, in which fieldwork is carried out where the main source of information will be interviews with promoters of tourism projects. The results show that Tajo-Salor County can be considered as a paradigmatic example of an “artificial” configuration of the territory, showing that, among those interviewed, there is no feeling of county. This has consequences on the assessment that local actors make of the implementation of the development program: those areas that do not feel part of the county have a much more negative assessment of the results obtained than the rest. This is a lesson that this case study offers; the political and technical managers of these programs should bear in mind in the future definition of the territories that apply this type of development strategy.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Study of the Configuration of the Territory as a Key Factor in Rural Development Strategies

Various documents published by the European institutions in the 1980s pointed to the need to strengthen the European rural milieu in view of the imminent adjustments to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) (European Commission 1981, 1985, 1988). In this context, at the beginning of the 1990s, the European Commission (EC) began to apply, on an experimental basis, endogenous rural development strategies based on the Leader I Initiative (Comisión Europea 1991). From then until now, this type of program has not ceased to be applied, although the way in which it has been implemented has evolved over time. Given the success of the first call for proposals, in the second half of the 1990s, the Leader II Initiative (Comisión Europea 1994) was approved, and at the beginning of the 2000s, the Leader+ Initiative (Comisión Europea 2000) was approved, which would be the last programming period in which this type of program would be implemented through a Community Initiative. Since then, they have constituted another axis of the funds corresponding to the so-called Second Pillar of the CAP, and their application is regulated by the corresponding regulations. In its origins, the response of the European rural environment to the Leader Initiative calls was such that some countries complemented this Initiative with the approval of development programs which, inspired by it, allowed them to meet the development needs of those territories that were excluded from the selection processes inherent in the Leader calls. This is the case of Spain and the two editions of the Rural Development Program (Proder I and Proder II) applied in the second half of the 1990s and the first half of the 2000s (MAPA 1996, 2002).

It was in the second half of the 1990s, with the announcement of the Leader II Initiative (Comisión Europea 1994), that the territorial implementation of the Initiative acquired notable relevance. This was despite the fact that it was not a major investment program but an Initiative of an experimental nature with regard to the viability of modest investments which, being implemented in rural areas, were to be characterized by their innovative nature (Castellano-Álvarez et al. 2020b, 2020c). Therefore, the key to understanding the success of the Leader Initiative lies not so much in the resources committed as in the method inherent in its implementation (González Regidor 2006), a method that is embodied in the so-called “Leader Approach” and that is common to the different calls under both the Leader Initiative and the aforementioned Proder Program.

The European Association for Information and Local Development (AEIDL) defines this approach on the basis of seven characteristics which, for the purposes of this research, include the following: (a) a territorial dimension in which the county is the sphere of action for implementing development strategies; (b) a bottom-up approach, ensuring the participation of the population in the implementation of the program; and (c) the system of governance, where the Local Action Group (LAG) is the highest decision-making body and will be made up of representatives of employers, social groups and local councils in the county.

The characteristics of the Leader Approach show the importance that the different editions of the Initiative attach to a correct definition of the territory; a territory which, following Esparcia Pérez and Tur (1999), must be understood not as a mere continent of resources and population, but as a critical element for the successful implementation of these program. In turn, this territorial approach is materialized in a specific sphere of action: the county. As opposed to a local (too small) or regional (too wide) sphere, the county is defined by Guiberteau Cabanillas (2002), p. 95, as “a territorial area that is sufficiently homogeneous to share problems and solutions”.

The territorial approach has been widely studied by the Leader Observatory. In order to assess the potential of a territory, this Observatory considers that factors such as the following must be taken into account: (1) physical resources and their management; (2) its culture and identity; (3) human resources; (4) available know-how and capacity to extend it; (5) quality of the governance system; (6) activities carried out in the territory and characteristics of the companies that carry them out; (7) markets and external relations; and (8) the image and perception (both internal and external) of the territory (AEIDL 1999). Along the same lines, Esparcia Pérez and Tur (1999), when referring to the elements that condition the competitiveness of a territory, point to human resources, the products obtained, economic resources, etc., but also highlight other less tangible factors such as the identity of the population with its territory, the feeling of belonging to it. The aforementioned authors warn of the risks that an incorrect definition of the territory can have for the implementation of a development strategy and point out that, in certain cases, the application of the Leader Initiative has forced the artificial configuration of certain territories.

The handicap of many of these factors that define the territory on which development strategies are based is, precisely, their intangible or immaterial nature; this fact adds even more complexity to their measurement or valuation. Among many others, Navarro Valverde et al. (2012), Esparcia (2001) and Delgado et al. (1999) recognize the difficulty of this endeavor and stress that systems of analysis that go beyond those usually used by institutions and consultancies in the evaluation of the impacts of rural development program are necessary; they are often focused on the strictly material and quantifiable.

Although this question has been approached from different points of view at a theoretical level, there is still a lack of examples, methodological proposals and practical cases that define measurement systems for these intangible aspects and study their consequences. In fact, this is the gap that this research aims to fill and which has already aroused the interest of the authors of this work in previous studies (Castellano-Álvarez et al. 2020a). Therefore, starting from the case of Tajo-Salor County (Extremadura, Spain), the aim of this research is to study the dimension of the territorial approach and the consequences that can be derived from it for the implementation of the development program. In order to achieve this objective, the following research questions have been formulated: (1) Does a sense of county identity exist in this territory? (2) How does its existence or non-existence influence the assessment of the program implementation by local actors? Finally, based on the results of the research, it is also intended to formulate practical proposals for action for the case of Tajo-Salor County.

1.2. Literature Review

As Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2022) point out in their methodological proposal for analyzing the long-term effects of rural development programs, the interest in evaluating the method is an alternative line of research to that which, for the most part, focuses on measuring the impacts derived from the application of these programs.

Based on their studies of La Vera County (Extremadura, Spain) and using a methodology similar to that applied in this research, Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2020a) study the assessment of the promoters involved in the implementation of the program with respect to the management system, the participatory approach or the territorial dimension inherent to the “Leader Approach”. The results of this work show a recognition of the capacity of rural development programs to strengthen county identity and indicate that actions such as tourism promotion campaigns, the county management system itself or investments in the recovery of heritage have contributed to this purpose (Castellano-Álvarez 2018; Castellano-Álvarez et al. 2021). However, it should be noted that, in general, interviewees also admitted that, in the case of La Vera, the county identity or the sense of belonging to the territory was an issue that already existed before the implementation of the program. Without leaving aside the case of La Vera, Castellano-Álvarez and Robina-Ramírez (2023b) return to the analysis of the territorial approach in rural development programs and conclude that, for the mayors of this county, the assessment of the implementation of the development program is clearly higher at the county level than at the strictly municipal level; in the opinion of the aforementioned authors, this would reflect the deep-rooted county dimension inherent in the implementation of this type of program.

The previous research attempts to evaluate something as intangible or immaterial as the perceptions of local actors on certain issues related to the development of their territory. In this effort, the aforementioned authors follow a similar methodological line to that used in other works (Castellano-Álvarez and Robina-Ramírez 2023a) or to that followed by many other researchers such as Gogitidze et al. (2023), Muresan et al. (2019), Harun et al. (2018), Oroian et al. (2017) and Dumitras et al. (2017).

Pérez Rubio (2007) studies the immaterial factors that condition the development of rural areas, and to do so, he employs a cross-cutting vision that emphasizes questions related to social capital. Also focusing on immaterial elements linked to social capital, Pérez Rubio and Gascón (2010) analyze the characteristics and motivations of neo-rurals in Extremadura (Spain). The analysis of social capital and its interrelations with endogenous rural development is an important line of research to which authors such as Esparcia et al. (2016), Saz-Gil and Gómez-Quintero (2015), Buciega (2012), Camagni (2003), Shucksmith (2002), Moyano Estrada (2001), Woolcock (1998), Putnam (1995) and Granovetter (1985) have made valuable contributions. Other works, such as those by Garrido Fernández and Moyano Estrada (2002), try to define indices that serve to quantify the impact of the application of the Leader II Initiative and the Proder I Program on the social capital of rural areas of Andalusia (Spain).

The interest in the study of social capital comes from the very characteristics of the Leader approach. Together with the territorial issue, the beginning of this section points out two other characteristics of the Leader methodology: the bottom-up approach and the governance system. In the implementation of rural development programs, the active participation of the population is key as a dynamizing element of the social capital of rural areas. Therefore, it is understandable that the bottom-up approach, the quality of the participatory processes implemented at the county level, is also a subject that has attracted the interest of many researchers. Ramos and Garrido (2014) fully address this issue when they try to relate the territorial differentiation strategies of the different LAGs with the involvement of local actors in the development strategies undertaken. Quaranta et al. (2016), Navarro Valverde et al. (2014), Navarro Valverde et al. (2016) and Alberdi Collantes (2008) are just some of the authors who have devoted efforts in this line.

After outlining the research approach and the theoretical framework, the following section deals with methodological issues; the third section shows the results of the research, and finally, the most relevant conclusions and some proposals for action are presented.

2. Methodology

2.1. Geographical Scope of the Research: Tajo-Salor County as a Case Study Object

Yin (2018) defends the usefulness of the case study methodology when the element to be studied is interdependent with its environment. In Tajo-Salor County (Extremadura, Spain), the definition of the territory, the active participation of its population in the development process conditions, without a doubt, the execution of the development program itself.

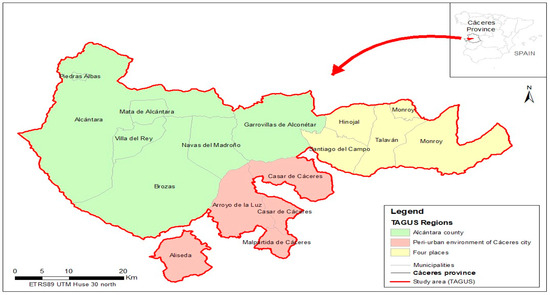

Coller (2000), as a prior condition to the application of this methodology, points out that it is necessary for the case under study to have its limits clearly defined. Leaving aside the skill with which it has been done, in the development strategy of Tajo-Salor County, the scope of action is made up of 15 towns that represent 2176.04 km2 of a territory characterized by its aridity (despite the fact that the rivers that give rise to the name of this LAG flow through it). Figure 1 represents the location and municipalities that make up Tajo-Salor County, delimited to the east by the municipal area of Cáceres (which completely surrounds Aliseda), to the west by the border with Portugal, to the north by the Tajo River and to the south by the Sierra de San Pedro (TAGUS 2016).

Figure 1.

Location and municipalities that make up Tajo-Salor County. Source: own elaboration.

As shown in Table 1, the temporal scope of the research refers to the execution of three programs (Proder I, Leader+ and Leader Approach) executed from the mid-nineties and the 2000s. Given that the current configuration of Tajo-Salor County is a consequence of the different projects developed by the towns of the area to opt for the management of rural development programs in their various calls, it is necessary to clarify that the Proder I Program (MAPA 1996) is executed by the Association for the Integral Development of Salor-Almonte (ADISA), composed of the municipalities belonging to the peri-urban environment of Cáceres City (Casar de Cáceres, Malpartida de Cáceres, Arroyo de la Luz and Aliseda), plus the so-called “Four Places” (Hinojal, Talaván, Santiago del Campo and Monroy). Subsequently, for the application of Leader+ (Comisión Europea 2000) and Leader Approach (Comisión Europea 2006), the TAGUS Association will be the result of the sum of the towns that made up ADISA and the municipalities that, within the Association for the Development of the Alcántara County (ADECA), they had managed, the first two calls for the Leader Initiative (Alcántara, Brozas, Navas del Madroño, Villa del Rey, Piedras Albas, Garrovillas and Mata de Alcántara). This sum of “realities” (not always coincident) may be one of the factors from which the absence of regional identity that currently afflicts the Tajo-Salor region is derived (Diputación de Cáceres 2016). Figure 1, while representing the set of municipalities that make up the region, also tries to differentiate the three subareas that compose it.

Table 1.

Sample of tourism projects in the Rural Tourism measure. Tajo-Salor County.

In research based on case study methodology, it is essential to justify why the chosen case is relevant to the issue to be studied (Coller 2000). The “forced” configuration of the TAGUS LAG is, ultimately, the cause of the problems of territorial identity of this county; it is, therefore, an object case, referring to a specific territory, but also an exemplary case, insofar as it represents a paradigmatic example for studying the difficulties and consequences derived for the application of rural development strategies from the absence of a territorial identity for the whole of the area over which the same strategy is implemented.

2.2. Fieldwork: Phases of the Research, Sample Selection and Interviews Conducted

The methodological approach of this work is very similar to that used by Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2023). In this case, this research raises new concerns, but, in relation to the methodology, the research phases and sources used are very similar.

The fieldwork was differentiated into three stages: in the first one, the LAG technicians were contacted, and the documents related to the development strategy of the region and the executed projects were accessed; in the second phase, based on the selection of a sample of the projects executed under the measure to promote rural tourism, the promoters were interviewed in person. These interviews are the main source of information for this research; they allowed the assessment of the aforementioned promoters regarding the cohesion of the territory and the level of the overall execution of the program; in the final stage, the results obtained in the interview phase were triangulated with the assessment of privileged actors in the territory.

In the aforementioned second stage of fieldwork, the sample of projects was carried out following three conditions: (1) the funds for the projects had to be mostly private; (2) the support of the public funds received must amount to at least EUR 12,000; and (3) the public aid received in the form of a subsidy must represent a minimum of 20% of the total investment made. These criteria are in line with those used by Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2023) and Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2019) and allow us to select a sample of projects representative of the execution of said measure, as shown in Table 1.

Of the 23 projects selected in the sample, 5 had ceased their activity and 1 had been transferred, so it was not possible to contact the initial promoters. As a consequence, fieldwork interviews were carried out with 17 promoters. In order to optimize the interpretation of the answers and to understand the objective of the projects carried out, the interviews were conducted at the place where their investments were implemented.

Regarding the interview model, it was decided to carry out semi-structured interviews. This type of interview facilitates the processing of the information and allows the incorporation of any opinion of interest that the interviewee may have, even if this, in principle, had not been foreseen by the interviewer. Yin (2016), in his considerations on qualitative research, justifies the validity of this interview model as a research tool and source of information. According to this author, this research tool allows one to interact with the person interviewed and contextualize his or her evaluations, thus promoting an optimal understanding of the answers of the person interviewed.

The structure of the interviews was divided into two phases referring to each of the research questions formulated at the end of Section 1.1. The first phase is concerned with the respondents’ sense of belonging to Tajo-Salor County. To this end, by means of a double open question, the promoters were asked the following: Do you believe that there is an idea of a county, do you feel you belong to the county? In the second phase, the assessment of the promoters regarding the contribution of the development program to their general objectives in Tajo-Salor County was obtained. For this purpose, the seven closed questions listed in Table 2 were defined. Regardless of the considerations that the promoters wished to make, in order to measure their evaluations, a Likert scale was used for each of the questions, whereby the interviewees had to rate from 0 to 10 the degree to which they believed that the development program had fulfilled the objective in question.

Table 2.

Closed questions asked of the promoters interviewed.

The final indices result from calculating the simple arithmetic mean of the scores received; in the event that any of the interviewees, for some of the questions, chose not to answer, their response for that specific question did not receive any score and was not taken into account in the calculation of the simple averages.

3. Results

3.1. Feeling of Belonging or Identity in the County

As Figure 1 shows, in Tajo-Salor County three areas can be differentiated: (1) the peri-urban environment of Cáceres City; (2) the four municipalities known as “Four Places” located to the east of the county, between which there has historically been a close connection, although they lack the necessary entity to be able to manage a development program on their own; and (3) Alcántara County, with its own identity and whose municipalities managed the first two calls for the Leader Initiative. Being fully aware of this heterogeneous reality, the first objective of this research takes its entire meaning.

Regarding the first research question, 15 of the 17 promoters considered that there is no such feeling of belonging to Tajo-Salor County. If the responses of the interviewees are analyzed based on their belonging to some of the indicated subareas, it is detected that the most negative evaluations are offered by the promoters of the “Four Places” and the peri-urban area of the city of Cáceres. The five interviewees belonging to the “Four Places”, while denying the existence of a real connection with the rest of the region, recognize that this feeling of identity does exist among the population of the “Four Places”. For their part, the seven interviewees from the peri-urban environment of Cáceres justify the non-existence of this feeling of county identity with three reasons: (1) their proximity to the city of Cáceres: “we are so close to Cáceres that we are detached of the county” argues one of the promoters while recognizing that, in her municipality “people feel like they belong to their town and the surroundings of Cáceres”; “We depend on Cáceres, which is the head of our county” justifies another; (2) a localist feeling: “don’t talk to me about the county; tell me about municipalities” responds one of the promoters; “here people are very closed in to their town,” another recognizes with a critical spirit; and (3) the absence of a “county tourism product” or “a county line of argument.”

Even those interviewed who, at first, responded that this sense of county did exist, when asked to define what Tajo-Salor County means to them, were not even aware that the municipalities of the “Four Places” also make up Tajo-Salor County. Some of them even went so far as to deny it (“for us the Four places are another place”), and they identified the idea of a county with their nearest municipalities.

As in the case of the “Four Places” promoters, among those interviewed from Alcántara County, a majority acknowledge a feeling of identity only with their closest area. Among this group of promoters, both those who offer more positive assessments and those who are more critical of this issue, it is common for them to justify the difficulty for this feeling of county identity to flourish on the basis of the great distances between the municipalities integrated into the Tajo-Salor LAG. One of the five promoters of this area is the only one who considers that this feeling of belonging does exist in the entire Tajo-Salor County “but… in a very relative sense” (he clarifies); there are also those who do not respond openly to the question but consider that this feeling “is being created”.

3.2. Assessment of Program Execution by the Local Promoters

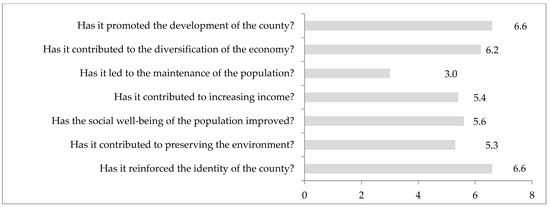

Having addressed the first objective of the research, the study turns to how the absence of this feeling of belonging to the entire region and how this territorial heterogeneity may have influenced the evaluation of the promoters regarding the achievement of the objectives set by the development programs. In this regard, Figure 2 represents the aggregate assessment of the promoters regarding the main objectives that, in general, endogenous rural development programs propose.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the program’s objectives by the promoters of Tajo-Salor County. Source: own elaboration.

As Figure 2 shows, with the exception of the program’s capacity to retain the population, in the rest of the matters raised, the aggregate rating exceeds 5 points. As is well known, depopulation and the aging of the rural population are two of the major challenges that many developed countries face with regard to their rural areas. These issues are, therefore, a fundamental objective of rural development programs; according to the results, it does not seem that those interviewed have a positive assessment of the role that the implementation of these programs is playing in this area in Tajo-Salor County. It is true that, in their answers, many of them also recognize that the economic resources allocated to this type of program are insufficient to meet such a challenge.

The results of the interviews show that the three areas in which the implementation of the program is most highly rated are its contributions to the development of the county, to strengthening the identity of the territory and to the diversification of its economy. Starting with the latter, this may be logical given that the interviewees are tourism promoters; they are therefore one of the best examples of the program’s contribution to the diversification of the economy. In the interviews, the order of the questions is the same as that given in Figure 2 and Figure 3; this was intended to go from the general to the most specific. Therefore, the local actors’ assessment of the program’s contribution to county development could be considered as the closest thing to an overall assessment of its implementation.

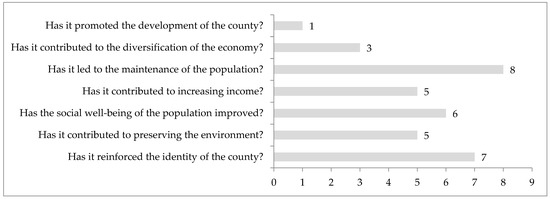

Figure 3.

Promoters who do not value the program’s contribution to some of its objectives. Source: own elaboration.

For its part, the positive assessment of the program’s capacity to reinforce county identity may seem paradoxical. In this regard, is worth clarifying that (1) these data must be assessed regarding the conclusions of the previous section where the lack of a feeling of belonging is recognized but, at the same time, paradoxically, the promoters also positively evaluate the effort made by the program in this matter. To such an extent is this the case that, with the exception of the interviewees belonging to the “Four Places”, most of the interviewees (11 out of 17) consider that the program has reinforced the county identity. The LAG’s own performance, its county logic of operation, is one of the factors that may have contributed to this (“TAGUS is a reference in the county and, with this, reinforces that identity”, says one of the interviewees). It should also be noted that, among the promoters who positively value the role of the LAG in this matter, there are those who critically qualify their response given the efforts made by the LAG in promoting Casar cheese, a product that, in their opinion, does not represent the entire county but only one of its towns. And (2) there is a methodological issue: the evaluations collected in Figure 2 are the average resulting from those offered by those who felt capable of giving their opinion on each of the questions raised. Figure 3 shows the number of interviewees who do not value some of the objectives in which the interviews are interested, and, after the demographic question, the role of the program in reinforcing the identity of the population with the territory is, precisely, the question for which the fewest evaluations are made.

This research aims to study the relevance of the articulation of the territory in the implementation of rural development programs. Having analyzed the feeling of belonging and the assessment that the promoters deserve for the execution of the program, it is now worth asking whether, given this territorial heterogeneity, this global assessment is homogeneous within the region or whether there are appreciable differences depending on the area of the county that is treated. Table 3 compares the assessment offered by the promoters of the entire county regarding the fulfillment of the program’s objectives with that offered by those same promoters but with their responses differentiated depending on the subarea of the county to which they belong.

Table 3.

Comparison by areas of the assessment of compliance with objectives.

As Table 3 shows, the capacity of the program to promote the development of the region and the capacity of the program to contribute to the diversification of its economy are two objectives in which the execution of the program is highly valued and, as Figure 3 shows, are the two issues that the promoters who feel qualified to offer their opinion believe could be an example of the visibility of the program in these matters. Regarding the sectors with which this economic diversification has been promoted, although references to tourism are frequent (the interviewees are tourism promoters), it is no less true that many promoters generalize their answers, referring to the training sector, livestock, etc.

The contribution of the program to the maintenance of the population is the subject that obtains the lowest rating in the county as a whole. To explain these results, it is necessary to return to Figure 3 which shows that almost half of the promoters do not value the role of the program in stopping demographic regression. However, both among those who did and among those who preferred to abstain, a feeling of discouragement in this matter is evident, and among a certain number of interviewees, there is also a feeling of understanding towards the limited resources of the program and the ambitious nature of this purpose. This is shown by some promoters when, regarding this question, they considered that “every day more people leave but TAGUS is not to blame for this” and “this problem is beyond the ability of TAGUS to act”.

The analysis of the data presented in Table 3 shows that the evaluations of the promoters around Cáceres and the Alcántara area are similar and, in both cases, higher than the average for Tajo-Salor County as a whole. However, in the case of the promoters of the “Four Places”, despite a positive assessment of the program’s contribution to the development of the county, the rest of the aspects raised have a much more negative perception. Examples of this would be the assessment of the program’s contribution to the maintenance of the population (0.0), reinforcement of identity of the county (0.0), environmental conservation (2.5) or social well-being (2.8); somewhat less unfavorable are the assessments of this group of promoters regarding the program’s contribution to economic diversification (4.5) or the increase in the population’s income (4.2).

The assessment of the promoters of the “Four Places” regarding the program’s contribution to reinforcing the feeling of belonging to the county could not be more negative. This could be a consequence of the uprooting of this area with respect to the territory with which it shares a development strategy, and ultimately, it could be the reason why the promoters of this area make a much more pejorative assessment of the implementation of the development program than the rest.

4. Discussion

Aside from the objectives of the research and the answers to the questions asked, this work constitutes an effort to try to measure what are known as intangible aspects of rural development. The aforementioned Navarro Valverde et al. (2012), Esparcia (2001) and Delgado et al. (1999) have already spoken about the difficulty and the need to face this task.

This work is in line with others carried out by Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2020c) on the intangibles of rural development in which an attempt is made to evaluate the characteristics of the Leader approach in the application of rural development programs. In line with the good assessment in Tajo-Salor of the program’s contribution to cross-cutting issues such as the development of the county or economic diversification, the results of the aforementioned work also showed a positive assessment of the role of the LAG. However, with regard to the contribution of the program to the identification of the population with its territory, there are differences between the results obtained by both studies; it is true that, in their analysis of the intangibles of rural development, Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2020a) take as a reference La Vera County in which, prior to the implementation of development programs, there was a deep-rooted sense of belonging and identity of the population with its territory. Be that as it may, both works show (a) that the suitability with which the territory is defined conditions the assessment of local agents regarding the results obtained with the execution of the development strategy and (b) that this conditions it structurally. That is to say, issues such as territorial identity are difficult to resolve in the short or medium term, despite the fact that, as concluded by Castellano-Álvarez et al. (2021), in the development strategy of Tajo-Salor County, an important part of the resources committed to non-productive measures have been directed to recovering heritage and cultural elements that strengthen that identity.

The results of this research show that the territorial definition of the Tajo-Salor co-brand can be considered forced, if not artificial. In relation to this issue, Guiberteau Cabanillas (2002) was already critical of the articulation of the LAGs in Extremadura and of the existence of a real participation of the population in them. Previously, Esparcia et al. (2000) argued their misgivings that the structures linked to the implementation of rural development programs were used as tools of legitimization and power by politicians, technicians or even some of those involved in the operation of these groups; this is not a trivial issue because, just as the territory is alive, the LAGs that implement development strategies should be flexible and creative; to what extent can the structures denounced by Esparcia et al. (2000) become elements that hinder or encourage the redefinition of the LAGs’ scope of action, the disappearance of some or the enlargement of others?

In their analysis of local people’s perceptions of tourism development, Gogitidze et al. (2023) and Baloch et al. (2022) argue that the tourism development of a territory depends, among other factors, on the specific characteristics of the area and its cultural heritage. Frînculeasa and Chiţescu (2018) understand that the absence of territorial identity, or of an adequate integration of its tourist resources, conditions the tourist development of the territory and, therefore, the evaluations that this type of promoter makes regarding tourism promotion strategies promoted by rural development programs. In line with the positions of all these authors, the research results show how many interviewees, to deny the existence of a regional identity, alluded to the absence of a “common tourist product” or “a line of argument that built the county”.

For their part, authors such as Saz-Gil and Gómez-Quintero (2015) or Garrido Fernández and Moyano Estrada (2002) have highlighted the relevance that social capital or the interactions of the local population can have in rural development processes and hence the importance of an optimal territorial configuration of LAGs to enhance the involvement of local agents. In relation to tourism development, Gursoy et al. (2019) consider that the lack of identification of the local population with the idea of the county would represent a handicap for the development of the territory; these authors emphasize the importance of LAGs actively involving the local population in the tourism planning and development of the territory as a way of promoting greater perception by them of the benefits of tourism. In fact, the results of the research show that in those areas of Tajo-Salor County where there is no sense of belonging to the territory, the interviewees’ assessment of the results obtained by the program is significantly more negative than in the rest.

5. Conclusions

Tajo-Salor County is a paradigmatic example of an artificially designed territory. There is no sense of county identity; in fact, the current configuration of the county is the result of the sum of different territorial realities in which the perception of the territory itself is not homogeneous: in the “Four Places” or in the peri-urban area of Cáceres city, the idea of a county is practically non-existent. The considerable distances between the different municipalities, or the fact that some of the areas integrated within the current county have historically had, and still have today, their own territorial identity, are two factors that make it even more difficult to construct the idea of a county territory.

The research shows that the lack of a sense of county identity has consequences for the assessment that local promoters make of the implementation of the development program. Those areas of the county that do not feel a sense of belonging to the county have a much more negative assessment of the results obtained with the implementation of the development program than the rest. The best example of this is the “Four Places”.

Therefore, territorial cohesion in the configuration of LAGs has a decisive influence on the assessment that local agents make of the implementation of development strategies. This is an interesting lesson that the case study of Tajo-Salor County offers, and that the political and technical managers of these programs should bear in mind in the future definition of the territories that apply this type of rural development strategy.

Regarding the limitations of the research, those linked to the methodology used and, in particular, the low number of interviews carried out (especially when the region is divided into subareas) should be noted. The results should be considered as an approximation to the subject matter under analysis and always interpreted in the context of the chosen case study. In future research, it could be interesting to extend the interview phase to the promoters of the rest of the productive measures; this could allow researchers to contrast whether the results obtained in the case of the “Four Places” show a certain feeling of uprooting from this area of the region or are a consequence of the bias introduced by the interviewees, given that in all cases, these are tourist projects with limited economic viability (as recognized by most of the promoters).

6. Proposals for Action in the Case of Tajo-Salor County

Perhaps, the linking of the “Four Places” with the area of influence of the Monfragüe National Park could make it advisable to reconsider the current composition of the county so that these municipalities would be incorporated in future programming periods into the Association for the Development of Monfragüe and its Environment (ADEME). In fact, three of these four towns border municipalities already integrated into the aforementioned ADEME. The “Four Places” could benefit the region’s economy, environment and development given the following:

- (1)

- Linking the “Four Places” to Monfragüe’s area of influence could boost eco-tourism and related economic opportunities. Monfragüe received over 300,000 visitors in 2021, benefiting hotels, restaurants, guides and artisans (Junta de Extremadura 2022). Incorporating the “Four Places” could extend this success; Talaván and Hinojal both have castle ruins that could attract cultural tourists (Diputación de Cáceres 2021).

- (2)

- The “Four Places” share Monfragüe’s exceptional biodiversity. They exhibit similar habitats like open oak woodlands, rocky slopes, river valleys and pastures (WWF España 2020). Annexing them could expand conservation for endangered species like the Spanish imperial eagle, black stork and black vulture (SEO BirdLife 2021).

- (3)

- Third, linking these areas would support Monfragüe’s sustainable development goals. Eco-tourism, artisanal food production, renewable energy and sustainable agriculture are priorities in addressing depopulation and unemployment (ADEME 2023). The “Four Places” face similar challenges to those faced by rural areas adjacent to these protected areas.

- (4)

- Grouping these municipalities could improve access to EU and regional development funding. Monfragüe municipalities receive over EUR 9 million annually for business support, training, infrastructure upgrades and environmental stewardship (Junta de Extremadura 2020). Access could aid projects in eco-businesses, heritage restoration, nature education and rural innovation in the “Four Places”.

- (5)

- Residents of the “Four Places” identify more with Monfragüe based on geography, landscape, history and culture (Ayuntamiento de Mirabel 2021). Incorporating them into ADEME could give them an amplified voice in local policies affecting daily life.

In turn, the relationship of Aliseda with the Sierra de San Pedro, or of the municipalities belonging to Alcántara County with the Portugal border, could make a merger of TAGUS with the Association for the Development of the Region of the Sierra de San Pedro-Los Baldíos advisable, placing the headquarters of the LAG in a locality intermediate to what would be the new territorial reality of this Group. There are several reasons that would justify these changes:

- (1)

- Aliseda and other municipalities bordering the Sierra de San Pedro have strong geographic, economic and social ties with the area that could warrant grouping them together (Vázquez 2021). Similarly, the Alcántara area depends on cross-border trade, tourism and transit with Portugal (Mérida 2020). Merging TAGUS with the Association for the Development of the Sierra de San Pedro Region could benefit both sides through increased funding, political visibility and administrative efficiency.

- (2)

- A merged entity could better access EU and regional grants for rural business support, training, infrastructure, nature conservation and cultural heritage programs (Moreno and López 2022; Sánchez-Oro Sánchez et al. 2021). The TAGUS municipalities already benefit from the Leader Approach for locally designed initiatives (TAGUS 2020). Joining forces under the same LAG would amplify these resources. It could fund priority projects like village repopulation, micro-enterprise assistance, renewable energy transitions, sustainable forestry and preserving dryland agriculture (ASPS 2021).

- (3)

- Combining these LAGs could also raise the political profile of rural priorities for depopulated areas struggling with unemployment and inadequate services (Diputación de Cáceres 2022; Leal-Solís and Robina-Ramírez 2022). A merged Association would cover one-third of Cáceres Province. Having a larger constituency could increase lobbying clout for budget allocations and decision-making input (González 2023).

- (4)

- Administratively, housing both associations under a single LAG structure would improve operational efficiency. Joint technical, administrative and management staff could reduce overhead costs (Sánchez 2020). Digital tools and shared offices could also streamline project approvals, monitoring, grant distribution and fiscal compliance (Villalba 2021). Strategically locating the headquarters between the TAGUS and Sierra de San Pedro territories would symbolize the equitable merger and facilitate access for residents of both areas (Pulido and Barrios 2022). Centrally situating leadership could support genuinely balanced development that addresses the needs of all communities being supported under the expanded Group (López and Gómez 2021).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R.; methodology, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R.; software, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R.; validation, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R.; formal analysis, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R.; investigation, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R.; resources, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R.; data curation, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R.; writing—review and editing, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R.; visualization, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R.; supervision, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R.; project administration, F.J.C.-Á. and R.R.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the promoters for their time and availability for the interviews, as well as the kindness shown at all times by TAGUS’s technical staff.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ADEME. 2023. Development Priorities for Sustainable Rural Communities 2023–2027. Cáceres: Association for the Development of Monfragüe and Its Environment. [Google Scholar]

- Alberdi Collantes, Juan Cruz. 2008. El medio rural en la agenda empresarial: La difícil tarea de hacer partícipe a la empresa en el desarrollo rural. Investigaciones Geográficas 45: 63–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación Europea de Información sobre Desarrollo Local. 1999. La competitividad territorial. Construir una estrategia de desarrollo territorial con base en la experiencia de Leader. Innovación y desarrollo rural. Cuaderno nº 6. Observatorio Europeo Leader. Bruselas: Asociación Europea de Información sobre Desarrollo Local. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación para el Desarrollo Integral del Tajo-Salor-Almonte (TAGUS). 2016. Estrategia de Desarrollo Local y Participativo (2014–2020). Casar de Cáceres: TAGUS. [Google Scholar]

- ASPS (Association for the Development of the Sierra de San Pedro Region and Los Baldíos). 2021. Development Priorities for Rural Communities 2021–2027. Valencia de Alcántara: ASPS. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuntamiento de Mirabel. 2021. Historical and Cultural Survey of Municipalities Surrounding Monfragüe National Park. Mirabel: Municipality of Mirabel (Ayuntamiento de Mirabel). [Google Scholar]

- Baloch, Qadar, Syed Naseeb Shah, Nadeem Iqbal, Muhammad Sheeraz, Muhammad Asadullah, Sourath Mahar, and Asia Umar Khan. 2022. Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 30: 5917–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buciega, Arévalo. 2012. Capital social y LEADER. Los recursos generados entre 1996 y 2006. Revista de Estudios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo Rural 14: 111–44. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, Roberto. 2003. Incertidumbre, capital social y desarrollo local: Enseñanzas para una gobernabilidad sostenible del territorio. Investigaciones Regionales 2: 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Álvarez, Francisco Javier. 2018. The Restoration of Religious Heritage as a Rural Development Strategy. In The Restoration of Religious Heritage as a Rural Development Strategy. Edited by José Álvarez-García, María de la Cruz del Río Rama and Martín Gómez-Ullate. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 129–47. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Álvarez, Francisco Javier, Amador Durán-Sánchez, María de la Cruz del Río Rama, and José Álvarez-García. 2020b. Innovation and Entrepreneurship as Tools for Rural Development. Case Study Region of Vera, Extremadura, Spain. In Entrepreneurship and the Community. A Multidisciplinary Perspective on Creativity, Social Challenges, and Business. Edited by Vanessa Ratten. Cham: Springer, pp. 125–40. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Álvarez, Francisco Javier, Ana Nieto Masot, and José Castro-Serrano. 2020a. Intangibles of Rural Development. The Case Study of La Vera (Extremadura, Spain). Land 9: 203. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Álvarez, Francisco Javier, and Rafael Robina-Ramírez. 2023a. Long-Term Survival of Investments Implemented under Endogenous Rural Development Programs: The Case Study of La Vera Region (Extremadura, Spain). Agriculture 13: 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano-Álvarez, Francisco Javier, and Rafael Robina-Ramírez. 2023b. La comarca como ámbito de intervención en los programas de desarrollo rural. El Estudio de caso de la comarca de La Vera. In Organización de la producción, Instituciones y Cooperación empresarial. Estudios aplicados para el desarrollo rural. Edited by Francisco Manuel Parejo Moruno, José Francisco Rangel Preciado and Antonio Miguel Linares Luján. Madrid: Dykinson, S.L., pp. 365–78. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Álvarez, Francisco Javier, José Álvarez-García, Amador Durán-Sánchez, and María de la Cruz del Río Rama. 2021. Ethics and Rural Development: Case Study of Tajo-Salor (Extremadura, Spain). In Progress in Ethical Practices of Businesses. A Focus on Behavioral Interactions. Edited by Marta Peris-Ortiz, Patricia Márquez, Jaime Alonso Gomez and Mónica López-Sieben. Cham: Springer, pp. 297–311. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Álvarez, Francisco Javier, Luís Carlos Loures, and Julián Mora Aliseda. 2022. Análisis de los efectos a largo plazo de los programas de desarrollo rural a partir de la metodología del Estudio de Caso. In Planeamiento ecológico en las Iniciativas de desarrollo. Edited by Julián Mora Aliseda, Rui Alexandre Castanho and Jacinto Garrido. Pamplona: Thomson Reuters Aranzadi. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Álvarez, Francisco Javier, María de la Cruz del Río Rama, José Álvarez-García, and Amador Durán-Sánchez. 2019. Limitations of Rural Tourism as an Economic Diversification and Regional Development Instrument. The Case Study of La Vera Region. Sustainability 11: 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano-Álvarez, Francisco Javier, María de la Cruz del Río Rama, and Amador Durán-Sánchez. 2020c. Effectiveness of the Leader Initiative as an Instrument of Rural Development. Case Study of Extremadura (Spain). Revista Portuguesa de Estudos Regionais 55: 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano-Álvarez, Francisco Javier, Rafael Robina Ramírez, and Ana Nieto Masot. 2023. Tourism Development in the Framework of Endogenous Rural Development Programmes: Comparison of the Case Studies of the Regions of La Vera and Tajo-Salor (Extremadura, Spain). Agriculture 13: 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coller, Xavier. 2000. Estudio de casos. Colección de Cuadernos Metodológicos. Madrid: CIS. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. 1991. Comunicación por la que se fijan las directrices de unas subvenciones globales integradas para las que se invita a los Estados miembros a presentar propuestas que respondan a una Iniciativa comunitaria de desarrollo rural (91/C 73/14). Diario Oficial de las Comunidades Europeas, 19 de marzo de 1991. Brussels: Comisión Europea. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. 1994. Comunicación por la que se fijan las orientaciones para las subvenciones globales a los programas operativos integrados para los cuales se pide a los Estados miembros que presenten solicitudes de ayuda dentro de una iniciativa comunitaria de desarrollo rural (94/C 180/12). Diario Oficial de las Comunidades Europeas, 1 de julio de 1994. Brussels: Comisión Europea. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. 2000. Comunicación a los Estados miembros, por la que se fijan orientaciones sobre la iniciativa comunitaria de desarrollo rural (Leader +) (2000/C 139/05), C 139/05. Diario Oficial de las Comunidades Europeas. Luxemburgo: Oficina de Publicaciones Oficiales de las Comunidades Europeas. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. 2006. Reglamento 1974/2006, de 15 de diciembre de 2006, por el que se establecen disposiciones de aplicación del Reglamento 1698/2005 del Consejo relativo a la ayuda al desarrollo rural a través del Fondo Europeo Agrícola de Desarrollo Rural (FEADER). Diario Oficial de las Comunidades Europeas, L/368. Luxemburgo: Oficina de Publicaciones Oficiales de las Comunidades Europeas. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M. del Mar, Eduardo Ramos, Rosa Gallardo, and Fernando Ramos. 1999. De las nuevas tendencias en evaluación a su aplicación en las Iniciativas Europeas de desarrollo rural. In El desarrollo rural en la Agenda 2000. Edited by Eduardo Ramos. Madrid: MAPA, pp. 323–44. [Google Scholar]

- Diputación de Cáceres. 2016. Estudio de Mejora del Posicionamiento Turístico Tajo-Salor-Almonte. Cáceres: Diputación de Cáceres. [Google Scholar]

- Diputación de Cáceres. 2021. Castles and Archaeological Sites in the Province of Cáceres. Cáceres: Instituto de Estudios de Cáceres, Diputación de Cáceres. [Google Scholar]

- Diputación de Cáceres. 2022. Report on Municipal Budgets and Provincial Decision-Making; Cáceres: Economic Development Department.

- Dumitras, Diana E., Iulia C. Muresan, Ionel M. Jitea, Valentin C. Mihai, Simona E. Balazs, and Tiberiu Iancu. 2017. Assessing Tourists’ Preferences for Recreational Trips in National and Natural Parks as a Premise for Long-Term Sustainable Management Plans. Sustainability 9: 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparcia, Javier. 2001. Las políticas de desarrollo rural: Evaluación de resultados y debate en torno a sus orientaciones futuras. In El mundo rural en la era de la globalización: incertidumbres y potencialidades. Edited by F. García. Madrid: MAPA, pp. 267–309. [Google Scholar]

- Esparcia Pérez, Javier, and Joan Noguera Tur. 1999. Reflexiones en torno al territorio y al desarrollo rural. In El desarrollo rural en la Agenda 2000. Edited by Eduardo Ramos Real. Madrid: MAPA, pp. 9–44. [Google Scholar]

- Esparcia, Javier, Jaime Escribano, and José Serrano. 2016. Una aproximación al enfoque del capital social y a su contribución a los procesos de desarrollo local. Investigaciones Regionales 34: 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Esparcia, Javier, Joan Noguera Tur, and María Dolores Pitarch Garrido. 2000. LEADER en España: Desarrollo rural, poder, legitimación aprendizaje y nuevas estructuras. Documents d Analisi Geográfica 37: 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 1981. Guidelines for the European Agriculture. COM (81) 608. Bulletin of the European Communities, Supplement 4/81. Luxembourg and Brussels: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 1985. Perspectives for the Common Agricultural Policy. The Green Paper of the Commission; Green Europe News Flash 33, COM (85) 333. Brussels: Communication of the Commission to the Council and the Parliament. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 1988. The Future of Rural Society. COM (88) 501. Bulletin of the European Communities, Supplement 4/88. Luxembourg and Brussels: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Frînculeasa, Mădălina Nicoleta, and Răzvan Ion Chiţescu. 2018. The perception and attitude of the resident and tourists regarding the local public administration and the tourism phenomenon. Journal of Business and Public Administration 9: 137–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido Fernández, Fernando E., and Eduardo Moyano Estrada. 2002. Capital social y desarrollo en zonas rurales: Un análisis de los programas Leader II y Proder en Andalucía. Revista Internacional de Sociología 60: 67–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogitidze, Giorgi, Nana Nadareishvili, Rezhen Harun, Iulia D. Arion, and Iulia C. Muresan. 2023. Exploring Residents’ Perceptions towards Tourism Development. A Case Study of the Adjara Mountain Area. Sustainability 15: 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Regidor, Jesús. 2006. El método Leader: Un instrumento territorial para un desarrollo rural sostenible. El caso de Extremadura, en González Regidor, J. (Dir.): Desarrollo Rural de Base Territorial: Extremadura (España). Badajoz: MAPA y Consejería de Desarrollo Rural de la Junta de Extremadura, pp. 13–90. [Google Scholar]

- González, M. 2023. Political Voice of Rural Communities in Extremadura. Journal of Rural Affairs 126: 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, Mark. 1985. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 91: 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiberteau Cabanillas, Antonio. 2002. Fortalezas y debilidades del modelo de desarrollo rural por los actores locales. In Nuevos Horizontes en el desarrollo rural. Universidad Internacional de Andalucía. Edited by Dominga Márquez Fernández. Madrid: AKAL, pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, Dogan, Zhe Ouyang, Robin Nunkoo, and Wei Wei. 2019. Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: A meta-analysis. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 28: 306–33. [Google Scholar]

- Harun, Rezhen, Gabriela O. Chiciudean, Kawan Sirwan, Felix H. Arion, and Iulia C. Muresan. 2018. Attitudes and Perceptions of the Local Community towards Sustainable Tourism Development in Kurdistan Regional Government, Iraq. Sustainability 10: 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Extremadura. 2020. EU Funds for Protected Areas in Extremadura 2020–2025. Badajoz: Department of Sustainability, Junta de Extremadura. [Google Scholar]

- Junta de Extremadura. 2022. Tourism Statistics for Monfragüe National Park 2021. Badajoz: Secretariat of Tourism, Junta de Extremadura. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Solís, Ana, and Rafael Robina-Ramírez. 2022. Tourism Planning in underdeveloped regions—What has been going wrong? The case of Extremadura (Spain). Land 11: 663. [Google Scholar]

- López, J., and A. Gómez. 2021. Achieving Locally-Designed Development Through the LEADER Approach in Cáceres Province. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Economics 14: 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mérida, F. 2020. Cross-Border Trade Flows Between Spain and Portugal in the Alcántara Region. Cáceres: University of Extremadura Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación. 1996. Programa Nacional Proder I; Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación.

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación. 2002. Real Decreto 2/2002, de 11 de Enero, por el que se Regula la Aplicación de la Iniciativa Comunitaria “Leader Plus” y los Programas de Desarrollo Endógeno Incluidos en los Programas Operativos Integrados y en los Programas de Desarrollo Rural (PRODER). Boletín Oficial del Estado, nº 11, 12 de enero de 2002; Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación.

- Moreno, L., and P. López. 2022. EU Rural Development Funds in Spain 2023–2027; Madrid: Ministry of Agriculture, Government of Spain.

- Moyano Estrada, Eduardo. 2001. El concepto de capital social y su utilidad para el análisis de las dinámicas del desarrollo. Revista de Fomento Social 56: 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, Iulia C., Rezhen Harun, Felix H. Arion, Camelia F. Oroian, Diana E. Dumitras, Valentin C. Mihai, Marioara Ilea, Daniel I. Chiciudean, Iulia D. Gliga, and Gabriela O. Chiciudean. 2019. Residents’ Perception of Destination Quality: Key Factors for Sustainable Rural Development. Sustainability 11: 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Valverde, Francisco Antonio, Eugenio Cejudo García, and Juan Carlos Maroto Martos. 2012. Aportaciones a la evaluación de los programas de desarrollo rural. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 58: 349–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Navarro Valverde, Francisco Antonio, Eugenio Cejudo García, and Juan Carlos Maroto Martos. 2014. Reflexiones en torno a la participación en el desarrollo rural. ¿Reparto social o reforzamiento del poder? LEADER y PRODER en sur de España. EURE 40: 203–24. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Valverde, Francisco Antonio, Michael Woods, and Eugenio Cejudo García. 2016. The LEADER Initiative has been a Victim of Its Own Success. The Decline of the Bottom-Up Approach in Rural Development Programmes. The Cases of Wales and Andalusia. Sociologia Ruralis 56: 270–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oroian, Camelia F., Calin O. Safirescu, Rezhen Harun, Gabriela O. Chiciudean, Felix H. Arion, Iulia C. Muresan, and Bianca M. Bordeanu. 2017. Consumers’ Attitudes towards Organic Products and Sustainable Development: A Case Study of Romania. Sustainability 9: 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Rubio, José Antonio. 2007. Los intangibles del desarrollo rural. Cáceres: Universidad Extremadura. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Rubio, José Antonio, and José L. Gurría Gascón. 2010. Neorrurales en Extremadura. Una aproximación a los flujos y orientaciones de los nuevos pobladores. El caso de Las Villuercas y Sierra de Gata (Cáceres). Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido, J., and V. Barrios. 2022. Strategic Planning for Sustainability in Rural Municipalities. Local Environment 27: 118–30. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert D. 1995. Bowling alone. American’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy 6: 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, Giovanni, Elisabetta Citro, and Rosanna Salvia. 2016. Economic and Social Sustainable Synergies to Promote Innovations in Rural Tourism and Local Development. Sustainability 8: 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Eduardo, and Dolores Garrido. 2014. Estrategias de desarrollo rural territorial basadas en las especificidades rurales. El caso de la marca Calidad Rural en España. Revista de Estudios Regionales 100: 101–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, M. 2020. Improving Efficiency in Local Development Associations and LEADER Groups. Journal of European Structural Funds 23: 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Oro Sánchez, Marcelo, José Castro-Serrano, and Rafael Robina-Ramírez. 2021. Stakeholders’ participation in sustainable tourism planning for a rural region: Extremadura case study (Spain). Land 10: 553. [Google Scholar]

- Saz-Gil, María Isabel, and Juan David Gómez-Quintero. 2015. Una aproximación a la cuantificación del capital social: Una variable relevante en el desarrollo de la provincia de Teruel, España. EURE 41: 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEO BirdLife. 2021. Important Bird Areas in Extremadura. SEO BirdLife for the European Commission. Madrid: SEO BirdLife. [Google Scholar]

- Shucksmith, Mark. 2002. Endogenous development, social capital, and social inclusion: Perspectives from Leader in the UK. Sociologia Ruralis 40: 208–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAGUS. 2020. Linking Rural Development Across the TAGUS Territory. Centre for Development of Renewable Energy Sources and Energy Efficiency. Casar de Cáceres: TAGUS. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, E. 2021. Tourism Development and Protected Areas: The Case of Sierra de San Pedro. Pasos: Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 19: 717–31. [Google Scholar]

- Villalba, E. 2021. Digital Transformation in Spanish LEADER Groups: Best Practices. Journal of Rural Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2: 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock, Michael. 1998. Social capital and economic development: Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory and Society 27: 151–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF España. 2020. Habitats of Monfragüe National Park. Environmental Conservation Program. Madrid: WWF España. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 2016. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).