4.2. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics are needed to obtain an initial picture of the behavior of the stock price index data explored for further analysis. Descriptive statistics include the mean, median, maximum, minimum, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis. The standard deviation measures the dispersion of the data, which shows how much risk there is in a stock market in this study. The skewness is a measure of the asymmetry in the spread of statistical data around the mean and which side of the distribution tail is more extended. The skewness of a symmetrical distribution is zero. Positive skewness indicates that the data spread has a long tail on the right side, and negative skewness has a long tail on the left side. This measure of skewness provides in-depth information about the contour and tendency of the distribution, thus enriching our understanding of its asymmetric characteristics. Kurtosis includes information on whether the stock price index distribution is standard, as measured by the height of the probability distribution. A kurtosis value of 3 is said to indicate a mesokurtic distribution of the data in line with normality. If the kurtosis exceeds 3, then the data distribution is said to be leptokurtic to normal. If the kurtosis is less than 3, the data distribution is flat (i.e., platykurtic) compared to normally distributed data.

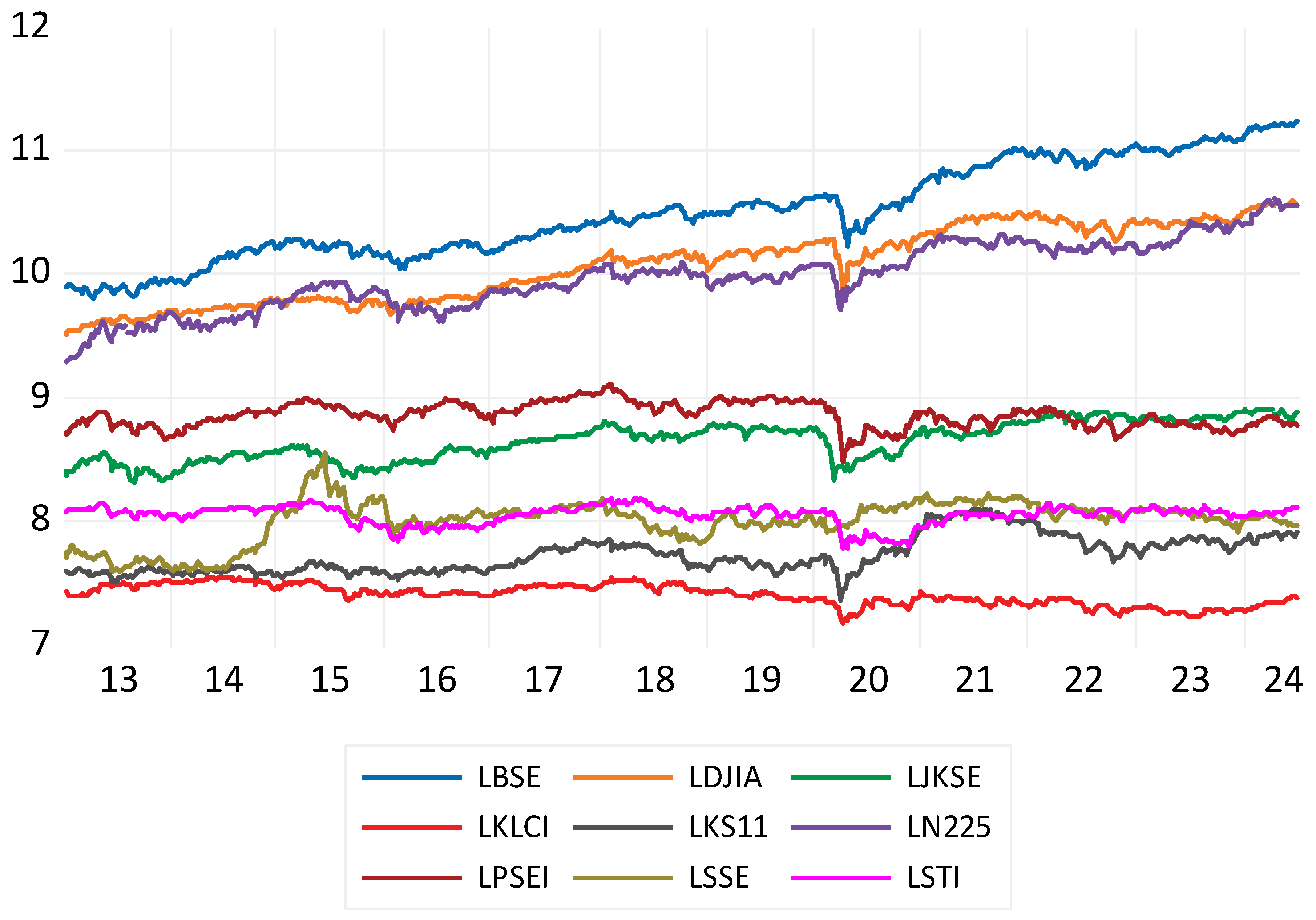

Table 2 shows the results of descriptive statistics that provide an overview of the performance of the stock indices of Indonesia and its major trading partners. During the sampling period, the BSE and DJIA had the highest average values, while the KLCI and KS11 had the lowest. The volatility of the stock price indices, as measured by the standard deviation, shows that the BSE and DJIA had the highest volatility, while the KLCI and STI had the lowest. Investors need to understand the importance of variance in the volatility levels of each market, especially when managing risk when considering a portfolio diversification strategy. The skewness results show positive skewness for the BSE and KS11, indicating that upward movements occur more often than downward movements.

In contrast, the other stock markets show negative skewness coefficients, implying that downward movements occur more often than upward movements. These skewness patterns indicate the potential opportunities and risks related to stock investment in each market, which are clues for investors who want to diversify their portfolios. All kurtosis coefficients displayed a platykurtic distribution during the study period, except for the STI and SSE. In addition, the Jarque–Bera test rejects the null hypothesis of a normal distribution, indicating a non-normal distribution of the data.

4.5. Johansen Cointegration Test

The ADF test results show that the weekly closing values of the stock price indexes become stationary in the first difference form, which allowed for the application of the cointegration procedure. The Johansen and Juselius cointegration technique was used to detect the integration of the Indonesian stock market and those of its major trading partners. The results of the Johansen-Juselius cointegration technique test are sensitive to the lag order chosen. Therefore, it is necessary to test the appropriate lag length criteria through the VAR lag order selection criteria. The optimal number of lags can vary based on the data and research questions, which aim to confirm uncorrelated residuals without unnecessary complexity. Five optimal lag selection criteria, namely, the LR test, Final Prediction Error (FPE), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Schwarz Criterion (SIC), and Hannan–Quinn information criterion (HQ). This study used the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) to determine the optimal lag length, which guides the cointegration test selection.

Table 5 presents the results of the optimal lag length test in the VAR system based on four criteria, namely, FPE, AIC, SC, and HQ, which suggested a lag of “2”. Therefore, a lag of “2” was selected to analyze the Indonesian stock market’s long-term and short-term joint movements with its major trading partners.

The analysis of the Indonesian stock market’s integration with those of its eight major trading partner countries was carried out using the Johansen and Juselius multivariate cointegration test. The Johansen and Juselius cointegration test results, based on the trace statistics and maximum eigenvalues, are presented in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

Table 6 presents the results of the multivariate cointegration test between the Indonesian stock market and those of its major trading partners. Based on the null hypothesis of zero cointegrating vectors, there was one significant cointegration vector with the trace statistic value. The eigenvalue of 220.302 is greater than the critical value of the trace statistic at the 5% confidence level.

Table 6 shows the results of the maximum eigenvalue statistics, which lead to the same conclusion as the findings for the trace statistics, for which there was one cointegrated vector. One cointegrated vector was identified, indicating a stationary long-term relationship between the Indonesian stock market and those of its main trading partners. In other words, the Indonesian stock market and those of its main trading partners are integrated, but the level is still low. This finding also reveals that the trade relationships between Indonesia and its main trading partners impact stock-market integration. The presence of cointegration also indicates convergence among the stock markets that occurs in the long term, with the cointegration results showing eight or four common trends. These results are related to the partial convergence of the index. If there is more than one common trend, this means partial convergence of the index. In addition, the Indonesian stock market and those of its main cointegrated trading partners show stable behavior in the long term. This finding provides an opportunity for long-term portfolio diversification in the Indonesian stock market for investors from Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines, China, India, South Korea, Japan, and the US. In addition, Indonesian investors can minimize risk by diversifying their portfolios internationally by investing in the stock markets of major trading partner countries.

This study’s results align with the findings of

Click and Plummer (

2005), who also proved that one cointegrated vector was found among the five ASEAN stock markets, meaning that the ASEAN5 are integrated.

Wu (

2020) revealed low integration between the ASEAN5 and East Asian (Japan, China, South Korea, and Japan) stock markets, although governments in both regions have supported stronger economic and financial cooperation.

Sher et al. (

2024) confirmed one cointegration vector, meaning a relatively low degree of comovement among the Japanese, US, Chinese, Australian, UK, and German stock markets. This finding provides an opportunity for long-term portfolio diversification in the Chinese stock market for investors from developed countries. Conversely, Chinese investors can reduce risk by investing in developed stock markets.

Chien et al. (

2015) found one cointegration vector in the comovement between the ASEAN5 and Chinese stock markets, meaning that the stock markets are integrated but increasing gradually.

Wang et al. (

2024) proved the existence of joint risk movements between the Malaysian stock market and its trading partners.

Caporale et al. (

2021) proved the existence of long-term dynamic relationships between the ASEAN5 and US stock markets, while China and the US were found to have no cointegration.

Paramati et al. (

2015) confirmed that trade intensity strengthens the interdependence of the Australian stock market and its trading partners.

Abdul Karim and Shabri Abd. Majid (

2010) proved the synchronization of the Malaysian stock market and those of its major trading partners. Different findings were revealed by

Gupta and Guidi (

2012), who found that India’s trade relations with its trading partners (Hong Kong, Japan, the US, and Singapore) had no impact on the integration of this stock market.

Teng et al. (

2013) revealed that the ASEAN5’s stock markets did not respond to external shocks from the following four trading partners: the US, Japan, China, and India.

Pairwise Granger causality tests were conducted on 36 bivariate between the Indonesian stock market and those of its major trading partners. The results of the paired Granger test, as presented in

Table 8, show 16 short-term bidirectional causality. The Indonesian stock market (JKSE) exhibited two-way causality with Singapore (STI), India (BSE), Japan (N225), and the United States (DJIA), which indicates a strong short-term relationship among the stock markets. The DJIA had the most two-way causalities with other countries’ stock markets, which excluded the JKSE, Malaysia (KCLI), the N225, South Korea (KS11), and the Philippines (PSEI). The US stock market strongly influences other countries’ stocks, especially Indonesia. The research results support the findings of

Robiyanto et al. (

2023), which proves the strong integration of the Indonesian and US stock markets, indicating that the movements of the two markets influence each other.

Endri et al. (

2020) proved that the Singaporean, Chinese, and US stock markets influence the Indonesian stock market.

Sarwar (

2019) confirmed that the US stock market strongly influences emerging markets. This raises concerns about the uncertainty of the US economy, which caused the US market’s risk factors to rapidly increase the volatility in this market.

Chevallier et al. (

2018) revealed that greater exposure to US shocks drove ASEAN stock market synchronization.

Yuliadi et al. (

2024) revealed different findings, where the Indonesian stock market only responded positively to the US stock market in the short term but not to the Japanese and Singaporean stock markets. These findings are due to the frequency of the data and study period used and the number of major trading partners included in the research samples.

The N225 also had the same amount of bidirectional causality as the US stock market, in addition to the N225 and JKSE, as well as the BSE, KLCI, and PSEI. Furthermore, there was bidirectional causality between the KLCI and the BSE and STI, and, finally, between the KS11 and the PSEI and STI. The SSE was the only country with no reciprocal causality relationship with any stock market. This finding indicates that the Chinese stock market is segmented, so it is isolated from the influence of changes in other countries’ stock markets, including Indonesia. The strong trade relations between Indonesia and China that have occurred recently have had no impact on increasing the degree of integration of the two countries’ stock markets. As Indonesia’s leading trade partner, China has contributed 26.3 percent of the total trade value. Singapore surpassed China’s foreign investment dominance in Indonesia, which included Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI). The latest data from the Indonesian Investment Coordinating Board show that the realization of foreign investment until the second quarter of 2024 totaled IDR 428.4 trillion, increasing by 6.7% quarter on quarter and growing by 22.5% year on year. China is second after Singapore for foreign investment in Indonesia, and FDI dominates Chinese investment.

Errunza (

2001) revealed that FPI significantly influences capital market integration. FDI is more attractive to Chinese investors because Indonesia’s degree of economic freedom is greater (

Azman-Saini et al. 2010).

Based on the 2024 Economic Freedom Index, Indonesia’s score is higher than China’s, at 63.5 compared to 48.5. However, the Economic Freedom Index of both countries decreased from 2020 to 2024. High economic freedom scores in trade and investment have been met with concerns over dependence on foreign investment, which can crowd out local businesses and increase economic vulnerability (

Szczepaniak et al. 2022;

Ahmad 2017). In addition, institutional quality affects economic freedom.

Liu et al. (

2021) show that a free market economy and strong institutions can increase FDI. Conversely, weak institutions can reduce FDI and economic growth (

Herrera-Echeverri et al. 2014).

Eldomiaty et al. (

2016) proved that economic freedom can reduce stock-market volatility. The US, Japanese, and Singaporean stock markets influence the Indonesian stock market. The research results align with

Yuliadi et al. (

2024), who found that the Chinese stock market has no short-term relationship with the Indonesian stock market.

Jinghua and Kogid (

2024) proved the increasing integration of China’s stock market with Singapore, Malaysia, and Vietnam but not with Indonesia.

Kenani et al. (

2013), using daily data, found that the Indonesian stock market moved in the same direction as China’s after the financial crisis.

The findings also confirm a strong short-run causal relationship between the Indian and Japanese stock markets. Using weekly data,

Wong et al. (

2005) also proved that the Indian stock market was integrated with Japan’s during the post-liberalization period.

Mukherjee and Bose (

2008) revealed that the Japanese stock market is synchronized with Asia, including India.

Gupta and Shrivastav (

2018) found a short-run and long-run dynamic relationship between the Indian and Japanese stock markets. Japan is noted to have a unique role in integrating the Asian stock markets, including India. India and Japan have strong economic ties and strategic geographical positions in both countries. In contrast, using daily data,

Tripathi and Sethi (

2010) found that the Indian stock market is not integrated with the Japanese stock market. These different findings imply that stock-market integration is a time-varying concept, and the results may depend on the frequency of the data used (

Bekaert et al. 2002).

The pairwise Granger causality test also identified unidirectional causal relationships between the Indonesian stock market and those of 10 of its major trading partners. The JKSE influenced the KLCI and PSEI unidirectionally, while the BSE, DJIA, PSEI, and N225 influenced the STI. The BSE had the most unidirectional causal relationships with the STI, KSII, DJIA, and PSEI, meaning that the Indian stock market influenced the Singaporean, Philippine, South Korean, and US stock markets. This finding is supported by

Song et al. (

2021), who stated that the Indian stock market is increasingly synchronized with Asian countries. This is because the economic relations between these countries and India have increased over time.

Pattnaik and Gahan (

2018) proved otherwise, showing that the Indian capital market is not affected by emerging stock markets. The KLCI also had a unidirectional causal relationship with the PSEI.

The Indonesian stock market influenced the Malaysian and Philippine stock markets because, in addition to the geographical proximity and the fact that both are members of ASEAN, they also have strong economic and financial relations.

Anhar et al. (

2024) proved that the Indonesian stock market has strong relationships with the Malaysian and Singaporean stock markets. The results of the Granger causality tests also identified ten stock market pairs that did not have a causal relationship, including the JKSE with the KS11 and SSE. The Chinese stock market (SSE) also did not have unidirectional relationships with the stock markets of other countries, including the US and Indian stock markets. Due to differences in regulations and trade wars,

Sher et al. (

2024) also proved no causal relationship between the US and China.

Eronimus and Verma (

2024) proved that the Indian and Chinese stock markets were integrated.