1. Introduction

Tourism is a powerful economic driver in many countries, influencing local economies and shaping urban development patterns. The relationship between tourism activity and housing markets is particularly significant in tourism-dependent economies like Croatia. Intensified tourism tends to impact the housing demand, prices, affordability, and land-use shifts at the destinations. A clear understanding of these dynamics is crucial to mitigating the risks coming from tourism by formulating policies that balance economic growth with housing affordability and sustainable urban development. Globally, housing units are increasingly being treated as investment assets with potential for economic rent extraction, emphasizing the concept of “rentierization” (

Ryan-Collins and Murray 2023). This trend is particularly pronounced in tourism-dependent economies such as Croatia, where several factors amplify its impact. Croatia’s high homeownership rate, coupled with the absence of property tax, creates a conducive environment for rentier practices. Additionally, the country’s tourism model, which is heavily dominated by private accommodations, exacerbates the issue. Recent research points out several negative consequences of such a tourism and housing market model in Croatia: it reduces housing affordability (

Mikulić et al. 2021), drives up housing prices in tourist areas (

Vizek et al. 2022), and limits business growth opportunities (

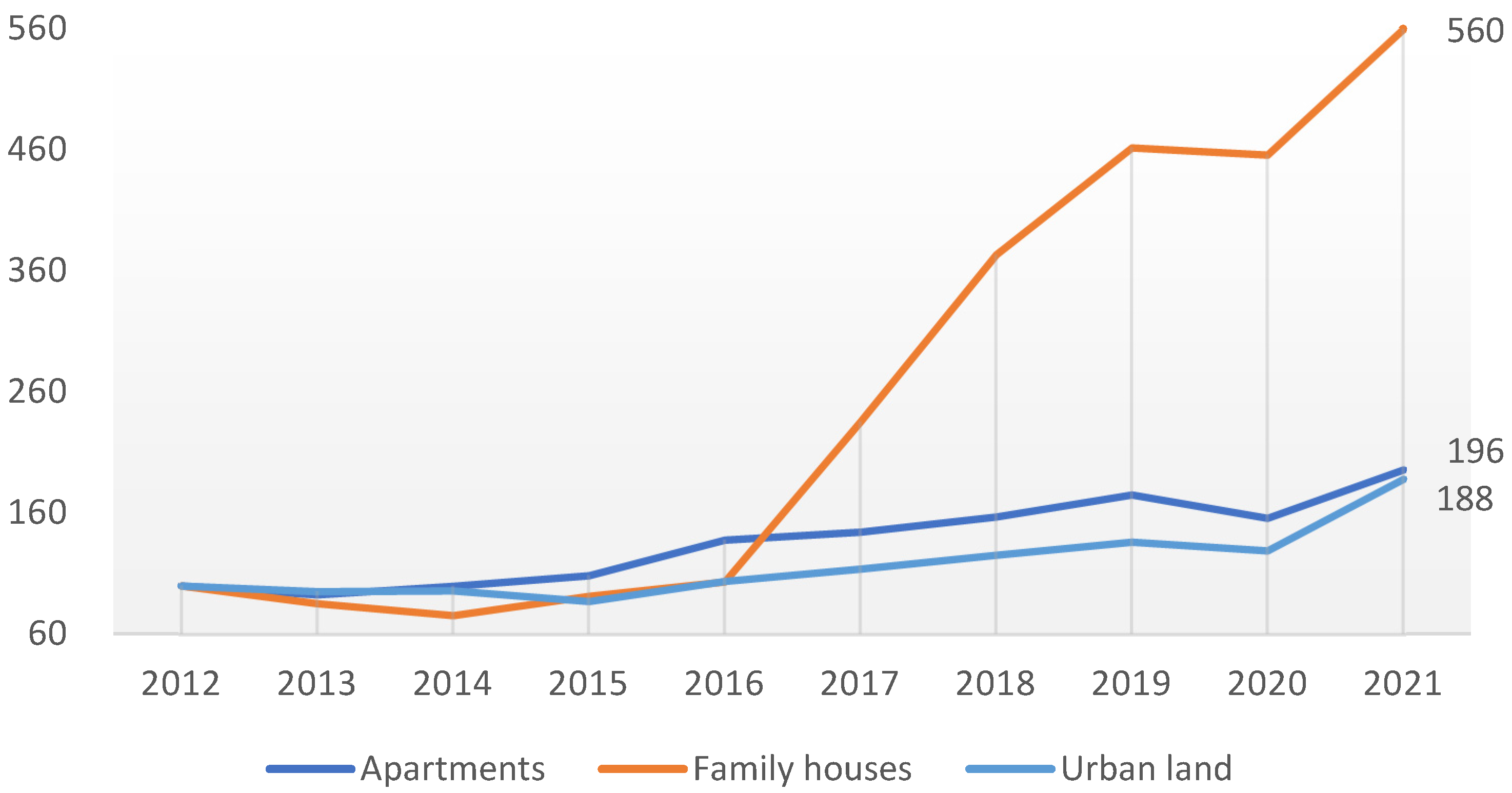

Stojčić et al. 2022). The dynamics of apartment, family house, and urban land purchases in Croatia in 2012–2021 are illustrated in

Figure 1.

The data indicate an upward trend in all property categories, reflecting growing demand and increased investment during the period. These dynamics underline the need for robust policy interventions to address housing market challenges while mitigating the broader economic impacts of tourism. Accordingly, this paper seeks to contribute to this critical discourse by exploring how tourism activity influences decisions to purchase housing units and urban land. Despite the growing body of research on the relationship between tourism and housing markets, existing studies have predominantly focused on its impact on housing prices and affordability (e.g.,

Biagi et al. 2015;

Mikulić et al. 2021;

Vizek et al. 2022). However, limited attention has been paid to how tourism activity influences households’ and investors’ decisions to purchase housing units or urban land. In addition to exploring tourism impact, this research examines how municipal environmental expenditures shape purchase decisions for apartments and family houses in Croatia. By incorporating data at the municipal level and employing a panel data model, this research provides detailed insights into the complex interplay among tourism, public spending, and housing markets. The results of this study provide policymakers and stakeholders with valuable ground for developing strategies that address housing demand in tourism-intensive areas while maintaining affordability and sustainability.

The findings of this paper provide evidence that tourism intensity is one of the drivers of urban housing demand, pointing out the need for policymakers to balance tourism growth with housing affordability through tailored zoning laws and incentives. Additionally, the paper underscores the importance of integrating environmental considerations into urban planning, suggesting that investments in green infrastructure and pollution control can enhance the desirability of locations for potential homeowners. These insights inform policymakers of the necessity of coherent housing policies that address both supply and demand while promoting sustainable urban development.

While addressing an important and underexplored aspect of urban development in tourism-dependent economies, this paper contributes new insights into the relationship among tourism, environmental policy, and housing demand, complementing existing studies by focusing on purchase decisions rather than solely on housing prices. An additional novelty of the paper is adding municipal environmental expenditures to the analysis, a variable often overlooked in previous research focusing on the relationship between tourism and the housing market in tourism-intensive economies. The decision proved justified, as the research findings confirm the critical role of environmental investments in shaping urban living conditions and driving housing demand. The results of this research have practical implications, seeking to provide evidence-based policy recommendations to address the challenges housing markets face in tourism-dependent economies. Focusing on Croatia, a European country heavily reliant on tourism, this paper offers context-specific findings relevant to other regions facing similar challenges.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 1 provides an introduction, and

Section 2 presents an overview of the current state of the literature.

Section 3 discusses the materials and methods utilized in the study. The results are presented in

Section 4, followed by a discussion that includes policy recommendations and suggestions for future research in

Section 5. Lastly,

Section 6 offers concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review

Various factors influence the dynamics of housing and land markets, ranging from macroeconomic conditions to microeconomic behaviors, demographic trends, tourism activity, and public policies. This section provides an overview of the relevant literature while emphasizing key contributions and gaps relevant to understanding the interplay among tourism activity, environmental policies, and housing market dynamics. The first stream of research is instrumental to understanding how factors such as household income, construction costs, interest rates, and inflation influence housing prices. While these studies provide valuable insights into price dynamics, they also help establish a foundation for understanding how these determinants may indirectly shape purchase decisions. By building on this stream of research, this paper seeks to extend the analysis beyond prices to explore how the same determinants, when mediated by tourism activity, influence transaction volumes. Macroeconomic factors, such as household income, construction costs, interest rates, and inflation, significantly affect housing prices and, consequently, the number of housing purchase transactions (

Sivitanides 2015). Rising household incomes increase purchasing power, enabling greater real estate investment. Similarly, lower interest rates reduce borrowing costs, encouraging mortgage uptake and housing purchases, while higher rates suppress demand. Inflation exerts a dual impact: it erodes purchasing power, reducing affordability (

Korkmaz 2020). At the same time, inflation might simultaneously increase the value of existing properties. The studies also found that real estate returns can act as a hedge against inflation (

Bond and Seiler 1998;

Wu and Pandey 2012). High construction costs can deter new developments, negatively limiting the supply of available homes while pushing the prices up. The accumulation of wealth for down payments and the availability of mortgage loans are also critical factors for housing purchases (

Moriizumi 2000). Besides facilitating down payments, wealth accumulation improves creditworthiness, making it easier to negotiate favorable mortgage terms. Social capital considerations, such as the relationship with parents and other relatives, the number of immediate relatives in the same city, and the educational background of families, are significant determinants of homeownership (

Yi et al. 2015). Demographic factors also influence housing purchase decisions. On a microeconomic level, individuals’ expectations about future housing market trends, influenced by recent housing price changes, along with their personal experiences and current homeownership status, may also affect their purchase decisions (

Kuchler et al. 2023). Consumers’ decisions on housing purchases are influenced by the characteristics of desired housing, including housing size, amenities, price, location, and environmental factors that are linked to the location (

Koklic and Vida 2011).

Seminal works in urban economics point out that the value of urban land primarily stems from its location and amenities. Foundational studies established the connection between amenities and land values (

Alonso 1964;

Brigham 1965). Other studies sought to quantify the willingness to pay for such amenities (

Nelson 1978). Additional demand factors that influence land values, including views, proximity to employment, and infrastructure availability, have also been elaborated on in the literature (

Grimes and Liang 2009). This paper explores implications for purchase decisions for housing units and urban land by leaning on the findings from price-focused studies.

Beyond macroeconomic and microeconomic factors, public policies can significantly influence housing and urban land purchase decisions. Policies affecting housing market trends and purchase decisions may result in public expenditures and focus on affordable housing, housing finance, urban planning, demographic outcomes, housing construction standards, taxation, and the environment. Affordable housing initiatives can make homeownership accessible to lower-income households (

Gurran and Whitehead 2011). Housing finance policies, including subsidies and mortgage interest deductions, can reduce the cost of homeownership (

Quigley and Raphael 2004). Urban planning policies can enhance the appeal of certain areas, while housing construction standards ensure quality and safety (

Bramley 1996). Taxation policies, such as property tax incentives, can also influence buying decisions (

Gihring 1999). Environmental policies can enhance the livability and sustainability of housing developments (

Moghayedi et al. 2022).

Local public spending also plays a vital role in housing markets.

García et al. (

2010) analyzed the effect of local public expenditures on housing prices in Barcelona, finding that investments in quality-of-life improvements, such as street maintenance, waste management, and recreational spaces, positively affect housing values. Similarly,

Li et al. (

2017) demonstrated that public service expenditures in Shanghai, particularly those enhancing service accessibility, influence housing prices, reflecting the capitalization of public investments into residential property values.

A substantial body of research has incorporated environmental variables into hedonic price models to analyze their impact on housing prices (e.g.,

Kestens et al. 2004;

Bolitzer and Netusil 2000;

Anderson and West 2006). However, their role in shaping housing demand in tourism-intensive regions remains underexplored. This study bridges the gap between policy-driven environmental considerations and their influence on housing demand in tourism-dependent economies by focusing on purchase decisions rather than solely on housing prices.

Tourism significantly influences land-use patterns and housing markets by altering demand priorities. The influx of tourists creates a need for accommodation and amenities, driving up land prices in tourist-heavy areas (

Biagi et al. 2015;

Kavarnou and Nanda 2018). The relationship between tourism and land-use patterns arises from the diverse ways land is utilized as a resource for tourism-related activities (

Boavida-Portugal et al. 2016). Tourism development leads to increased demand for construction land and continuous spatial disruptions in landscapes (

Mao et al. 2014).

Mao et al. (

2014) concluded that even strict land regulation policies do not necessarily improve land-use patterns. Tourism activity can exert considerable influence on construction land prices by altering demand patterns and land-use priorities. In this context, this paper is interested in exploring further how tourism activity and municipal expenditures on environmental protection and improved housing conditions affect housing and urban land for housing construction purchases. In Croatia, where tourism is a significant economic driver, these factors interact in complex ways to shape housing market outcomes. In recent periods, research has become highly focused on the relationship between tourism activity and various housing market outcomes, offering ample evidence in favor of higher housing prices in tourist destinations (

Biagi et al. 2015;

Kavarnou and Nanda 2018;

Balli et al. 2019;

Paramati and Roca 2019). Additionally, extensive research relates intensive tourism activity to lower housing affordability (

Lee 2016;

Mikulić et al. 2021;

Chen et al. 2022;

Vizek et al. 2022). By focusing on households’ and investors’ purchase decisions rather than solely on prices, this study offers a novel approach that complements existing research and provides a deeper understanding of the behavioral dynamics driving housing and urban land market activity in tourism-dependent economies.

3. Materials and Methods

This analysis seeks to offer a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing housing market activity at the city and municipality levels in Croatia from 2012 to 2021. To identify the determinants of the number of purchase transactions, a statistical analysis was conducted by using data from a total of 556 Croatian cities and municipalities. Only cities and municipalities with recorded transactions in a given year were included in the analysis, which resulted in 196, 375, and 459 cities and municipalities being included in the apartment, family house, and urban land models, respectively. This analysis focuses specifically on the number of purchase transactions for apartments and family houses. Additionally, the study explores the factors influencing the number of purchase transactions for urban land, which are critical, as they lay the groundwork for future housing unit construction.

This research study followed a structured approach, beginning with compiling an extensive and unique dataset incorporating variables related to housing transactions, demographic and economic indicators, tourism activity, and municipal expenditures. Such a dataset is exceptionally rare in housing market studies encompassing an entire country at the granular level of cities and municipalities (in this case, 556 units). Its curation and compilation significantly contribute to the literature, as it provides a uniquely detailed perspective rarely available in similar research. Next, the data were pre-processed to address missing values, ensure consistency, and prepare for analysis. Original data values were used without log transformations as absolute amounts (

Sirmans et al. 2005), as the dataset met the assumptions required for the chosen model specifications. Subsequently, a panel data model with a random effects estimator was selected based on theoretical considerations and statistical tests. The analysis was then conducted separately for apartments, family houses, and urban land purchases to capture the specific dynamics within each market segment. Finally, robustness checks were performed to validate the model outputs, including heteroscedasticity and the joint significance of regressors. Performing additional robustness checks was constrained by the uniqueness and granularity of the dataset. Substituting the variables with similar indicators for validation purposes was not feasible, as data for local government units in Croatia are less abundant than datasets available for entire countries.

For the analysis of apartments, the panel data model was estimated by using data collected from 196 cities and municipalities. For family houses, the model encompassed 375 cities and municipalities, while for urban land purchases, it included 459 cities and municipalities. These models help identify various factors that influence purchase transactions in different housing categories.

For municipality/city

i in period

t, our models can be expressed as

Here, Xit denotes the vector of control variables described in this section for each model, and ε represents the idiosyncratic errors.

The database used for the assessment, in addition to the number of purchase transactions and median apartment, family houses, and urban land prices, also contains data related to demographic and migration statistics (vitality index and net migration), population density, and present and future new-housing supply (surface area of newly finished housing units) and the number of newly issued housing unit construction permits. The housing prices are directly linked to transaction volumes, as higher prices often demotivate purchases due to affordability constraints, while lower prices stimulate demand. Demographic factors such as population density, migration trends, and natural population change are well-documented determinants of housing demand (

Leishman and Bramley 2005;

Biagi et al. 2015;

Kuchler et al. 2023). Population density reflects the spatial pressure on urban land, while net migration captures the movement of residents into or out of an area, directly influencing housing market activity (

Leishman and Bramley 2005). The vitality index, which measures natural population growth, indicates the long-term sustainability of housing demand in a locality. Housing supply metrics, including the number of newly completed housing units and issued building permits, provide insights into the responsiveness of housing supply to demand pressures and are widely used in empirical studies to analyze housing market trends (

Bramley 1996;

Sirmans et al. 2005;

Mikulić et al. 2021). Therefore, a positive correlation between supply indicators, housing units, and urban land purchases is expected.

The employment level is used as an indicator of housing demand, and the number of people employed in the construction industry is used as an indication of demand for urban land. Tourism activity is proxied by the number of overnight tourist stays per capita of a local city or municipality and the number of short-term rental units. Overnight stays per capita serve as a proxy for the intensity of tourism and its spillover effects on local housing markets (

Biagi et al. 2015), while the prevalence of short-term rentals reflects the transformation of housing stock into investment-oriented assets. These indicators align with evidence that tourism influences housing demand through increased competition between residential and rental markets (

Barron et al. 2021). To control for the effect of local public policies on housing purchases, two proxies for city and municipality policies that may positively influence housing and urban land purchase decisions are included: expenditures on environmental protection and expenditures on housing. Local government spending on environmental protection and housing conditions significantly impacts the desirability of urban living spaces. Similarly, municipal housing expenditures influence the availability and quality of housing stock while shaping purchase decisions. Finally, controls for larger cities (all cities that have more than 35 thousand inhabitants), coastal cities and municipalities, and cities and municipalities that are situated on an island are introduced, which is similar to the approach in

Biagi et al. (

2015) and

Mikulić et al. (

2021). Croatia’s geographical diversity results in significant variations in tourism activity across its cities and municipalities. Coastal and island municipalities are highly tourism-oriented, whereas continental municipalities generally experience lower levels of tourism activity.

The same model specification is used for apartment and family house purchases, with one notable difference. In the case of apartment purchases, median apartment prices are used to control for housing market conditions, while median family house prices are used for family purchases. For urban land prices, the model is specified somewhat differently, as it controls for the city’s expenditures for housing, net migration balance, and the number of short-term rentals instead of expenditures for environmental protection, vitality index, and the number of overnight tourist stays that are used for apartment and family house purchase models. It is also the only model which controls the number of construction industry employees. Housing market conditions and expectations are proxied with median apartment and urban land prices.

The variables used in this analysis are comprehensively detailed in

Table 1, providing a clear overview of the data sources and their application within the study. Most of the variables are sourced from the Croatian Bureau of Statistics (CBS), the national statistical office. At the same time, data on housing transactions and prices are provided by the Institute of Economics, Zagreb (EIZ), through their annual real estate trend reports prepared for the Croatian Ministry of Physical Planning, Construction, and State Assets. The data on environmental and housing expenditures are provided by the Croatian Ministry of Finance. The last column specifies the model in which each variable is employed.

4. Results

The results of the assessment are presented in

Table 2. The findings suggest that important determinants of the movement in the number of apartment purchases are the median price of an apartment, the vitality index, the surface area of completed housing units, the number of issued building permits, employment level in the local unit, the number of tourist nights per inhabitant, and the expenditures from the budget of local self-government units for environmental protection.

As the median price of an apartment increases by HRK 1000 per m2 (approximately EUR 132), the number of transactions decreases by 9, likely due to expectations of market overheating. At the same time, an improved demographic situation indicated by an increase in the value of the vitality index decreases the number of apartment transactions. These effects are also present in the model for family houses. An increase in the surface area of completed new housing units and an increase in the number of issued building permits for housing units have a slightly positive impact on increasing the number of apartment purchases, which may suggest that apartment purchases increase as the planned future construction and current supply of higher quality residential space in the market increase. This effect is also present in the models of family houses and construction land but with a lower magnitude. The increase in the number of employed inhabitants in a city or municipality is associated with an increase in the number of apartment purchases, which can be attributed to the positive effect of improved local economic conditions on apartment purchase decisions. The same effect is also present in models for family houses and urban land purchases; however, the magnitude of the effect is ten times higher for apartment purchases when compared with family houses and urban land purchases.

In line with expectations, an increase in the intensity of tourist activity measured by the number of tourists overnight stays per inhabitant of a city or municipality is associated with an increase in the number of apartment purchases. Thus, an increase in the number of nights per inhabitant by 1000 on average increases the number of apartment purchases by 1. This effect can be attributed to several factors related to tourism activity. As tourism activity in a city or a municipality intensifies, one would expect that more tourism-related amenities are offered, and better infrastructure is built to support more intensive tourism activity. Both can, in turn, improve the quality of life in that city or municipality and thus make a city or a municipality a more desirable location for permanent occupation, which may motivate more apartment purchases in that location. In this context, the literature on hedonic price models that examine amenities’ impact on housing price valuations can be particularly insightful. These models capture how the enhanced quality of life provided by these amenities is reflected in housing values, and many studies support the positive impact of amenities on housing prices (

Bolitzer and Netusil 2000;

Anderson and West 2006;

Nicholls and Crompton 2007). In addition, an intensification in tourism activity also offers more opportunities for increasing household income, be it through employment or the short-term renting of housing units, which can also motivate apartment purchases. More apartment purchases in places that exhibit more intensive tourism activity could also result from the domestic and foreign demand for secondary residences.

Results, however, suggest that the positive association between tourism activity and housing unit purchases is not present in the case of family houses, which do not seem to be affected by the changes in the level of tourism intensity. This may suggest that households perceive apartments, and not family houses, as the most important vehicle through which they could realize dwelling benefits that arise with more intense tourism activity. The preference for apartments as primary investment vehicles in tourism-intensive areas can be attributed to a combination of economic, social, and cultural factors. These include the high rental income potential, strategic location advantages, affordability, lower maintenance costs, and alignment with urban living trends. The coefficient of determination for Model 2 is lower compared with the other models, which has been recognized and accepted in the literature (e.g.,

Green and Hendershott 1996;

Lerbs 2014) and is often linked with the intrinsic complexity of factors influencing family house transactions. Additionally, compared with the relative uniformity of apartments or urban land, the heterogeneity of family houses contributes to the lower explanatory power. Even though adding additional variables could enhance Model 2 explanatory power (

Sirmans et al. 2005;

Hill 2011), its statistical significance and consistency with theoretical expectations point out its reliability and the value of its insights.

An increase in expenditures from the budget of local units for environmental protection is also associated with an increase in the number of apartment purchases, suggesting that cities that invest more in environmental protection increase quality of life and living conditions in a city or municipality. This effect is also significant in the family house purchase model; however, in the case of apartment purchases, it is four times as strong.

Estimates for the urban land purchase model suggest that the number of purchases is influenced by the median price of apartments, net migration balance, surface area of completed housing units, issued building permits, the total number of employees, the number of employees in the construction industry, the number of short-term rentals, and expenditures from the budget of local government units for housing. The increase in short-term rentals is positively associated with urban land purchases. For every 1000 newly registered short-term rentals in a city or municipality, three additional urban land purchases are made on average. Here, one could conclude that the potential for future profits from short-term rentals and not the overall level of tourism activity drives demand and urban land purchase decisions. At the same time, an increase in housing expenditures from the budget of a city or a municipality is associated with an increase in urban land purchases in an average city or a municipality. The impact is not as strong as in the case of local environmental protection expenditures, but it is nevertheless statistically significant.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study underline several important insights into the interplay among tourism activity, environmental expenditures, and urban land and housing market dynamics in a tourism-dependent economy. Firstly, the positive correlation between tourism intensity and apartment purchases suggests that tourism can significantly drive housing demand, in this case in terms of the number of purchases. Although focusing on the number of purchases, such findings complement the existing literature evidence on the increase in housing prices on the back of tourism due to increased accommodation demand from tourists and investors seeking rental opportunities (

Biagi et al. 2015;

Balli et al. 2019; (

Cunha and Lobão 2021). The inflow of tourists and the development of short-term rental platforms create a market for short-term rentals, which in turn increases the attractiveness of apartments as investment assets and may lead to a reduction in the availability of long-term rentals (

Barron et al. 2021). Additionally, tourism increases the availability of tourism-related amenities, which improves the quality of life in tourist destinations (

Vizek et al. 2024) and further stimulates the demand for housing units and urban land. For policymakers, our findings imply a need to balance tourism growth with local housing affordability. Policymakers should consider implementing zoning laws and tax incentives that promote sustainable tourism while ensuring high quality of life and affordable housing for long-term residents. In addition, this study complements the existing literature by shifting the focus from housing prices to purchase decisions. Such an approach empowers policymakers with actionable insights for designing more effective and targeted policies.

The importance of the supply-side factors has been confirmed by the positive relationship among the surface area of completed housing units, the number of issued building permits and the number of apartment purchases. The same trend with a lower magnitude is observed in the models for family houses and urban land purchases. These findings imply the need for policies that facilitate new-housing development as a means of maintaining housing market activity and addressing housing demand. Consistent with

Bramley (

1996) and

Sirmans et al. (

2005), the results suggest that policies facilitating new-housing development can play a pivotal role in sustaining housing market dynamics.

This study emphasizes the role of municipal environmental expenditures in shaping housing demand for apartments and family houses in a tourism-dependent economy. The positive relationship between municipal environmental expenditures and housing unit purchases reflects the growing importance of plugging environmental quality information into purchase decision making in the market. In other words, local governments’ investments in environmental protection improve quality of life, making these cities and municipalities more attractive to potential buyers.

Gurran and Whitehead (

2011) also support arguments for the significance of urban planning and sustainability initiatives. In addition, these findings resonate with broader research on the influence of public expenditures on housing market dynamics. Studies have demonstrated how targeted public spending on quality-of-life improvements (

García et al. 2010) or public service accessibility (

Li et al. 2017) shapes housing values. While those studies focus on capitalizing public investments into property prices, this research adopts a unique approach by examining municipal environmental expenditures as a driver of housing demand in a tourism-dependent economy. While shifting the focus from price appreciation to the behavioral dynamics of purchase decisions, this study provides a deeper understanding of how public policies interact with market forces in tourism-intensive regions.

The results of this analysis indicate that the increase in short-term rentals is positively associated with urban land purchases, suggesting that investors view urban land as an asset for future development in tourism-intensive areas. This result complements studies reporting on the influence of short-term rentals on housing markets (

Barron et al. 2021;

Chen et al. 2022). The revealed relationship between short-term rentals and urban land purchases presents opportunities for real estate investors but requires careful oversight by policymakers at both the national and local levels. To prevent housing shortages and affordability issues in local communities, strategies such as regulating the number of short-term rental licenses or taxing short-term rental income at higher rates should be considered. The increase in housing prices can also be partly attributed to foreign demand, which may further reduce housing affordability for residents (

Paramati and Roca 2019).

Paramati and Roca (

2019) conclude that such developments may lead to negative perceptions about tourism by local communities despite the high returns on property investments. Finally, the results of this analysis lay the foundation for further exploration of the dynamics of “rentierization” in Croatia and other tourism-driven economies worldwide. Housing assets, particularly urban land and apartments in tourism-intensive areas, are increasingly used as investment vehicles rather than serving primary residential needs. Such a shift intensifies housing affordability challenges, as residents face growing pressure from investment-driven demand, further reducing opportunities for affordable housing. These findings call for careful policy interventions, such as regulating short-term rentals or promoting affordable housing initiatives, to mitigate the adverse effects of “rentierization” on housing availability and affordability for local communities.

6. Conclusions

This paper examines the interplay among tourism activity, municipal expenditures, and urban housing market dynamics in Croatia, focusing on the purchase decisions for apartments, family houses, and urban land. A random effects panel model is employed with a granular and unique dataset of cities and municipalities in Croatia, a country heavily reliant on tourism. The findings indicate that increased tourism at a destination encourages buying apartments, but this does not appear to influence the purchase of family houses. This finding may suggest that households perceive apartments, not family houses, as the most prominent vehicle for realizing the dwelling benefits that arise from more intense tourism activity. Conversely, municipal investments in environmental protection, often essential in areas dependent on tourism, positively correlate with purchasing apartments and family houses, with a more pronounced effect on apartment purchases. The rise in urban land purchases for housing construction is also linked with increased short-term rentals and higher municipal housing expenditures. The former finding suggests that households perceive that the potential for future profits from tourism activity stems from the increase in short-term rentals and not the overall level of tourism activity, which drives the demand for urban land for housing construction and its purchase decisions. Investors can use these findings to identify high-demand housing segments and locations. The positive relationship between short-term rentals and urban land purchases indicates potential profitability in tourism-intensive areas. However, such developments may further stimulate rentier economy practices and deteriorate housing affordability for residents, and this needs to be adequately addressed.

Consequently, the results described in this analysis have important implications for policymakers. First, policymakers should consider improving zoning laws and tax policies to balance tourism growth with housing affordability; possible policies include limiting the conversion of housing stock into short-term rentals or incentivizing long-term rentals. In addition, local governments should promote investments in environmental protection and the sustainable development of the local communities, which will also positively affect the housing market. Finally, adequate policies should target urban land purchases in tourism-intensive areas to prevent speculative activities and ensure land development aligns with community needs, keeping affordability challenges for residents in mind.

Some limitations to this study’s approach are worth considering. Since the analysis is specific to Croatia, there is a limited opportunity to generalize findings to other tourism-dependent economies with different socio-economic and policy contexts. In addition, this study focuses primarily on quantitative indicators while neglecting qualitative factors, such as community perceptions of tourism or specific local housing policies. Although unique and granular, the dataset does not account for potential macroeconomic shocks, such as pandemics, which could influence housing and tourism markets. Future research should investigate similar dynamics in other tourism-dependent contexts to verify the validity of the findings. Future research would benefit from including additional variables, such as climate change impacts, the energy efficiency of housing stock, and public sentiment toward tourism. Finally, future research should focus on identifying and evaluating policy mechanisms that effectively mitigate housing market distortions and counteract “rentierization” practices in tourism-driven economies.