Abstract

Interactions between monetary and macroprudential policy are crucial in safeguarding price and financial stability. This study investigates the macroeconomic and financial impacts of monetary and macroprudential policy interactions in South Africa, a leading African economy in developing macroprudential frameworks. The existing literature largely focuses on the effectiveness of these policies independently, leaving a gap in understanding how their interaction affects their overall efficacy. Employing a Structural Vector Autoregression (SVAR) model and utilizing data from 1980 to 2023, this study uniquely incorporates the financial cycle to represent financial developments. The results reveal significant effects of both policies on key variables such as output, the financial cycle, and the price level. Specifically, policy contractions reduce output and the financial cycle but increase the price level, illustrating the ‘price puzzle’. This study further identifies an endogenous response between the two policies: monetary policy reacts by rising to reduce price levels following a macroprudential shock, while macroprudential policy rises to stimulate financial activity after a monetary shock. These findings underscore the importance of using both policies in conjunction but in opposite directions to balance their effects and achieve price and financial stability. This study suggests that an optimal combination of monetary and macroprudential policies is critical for maintaining macroeconomic equilibrium.

1. Introduction

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis (GFC), there has been a burgeoning interest in the effectiveness of monetary and macroprudential policies in safeguarding price and financial stability within inflation targeting (IT) economies. Scholars and academics have highlighted a significant deficiency in monetary policy within the IT framework, namely its inability to simultaneously target both price and financial stability (Kim and Mehrotra 2017a). This challenge arises because monetary policy often neglects systemic risk developments, leading to the unchecked accumulation of financial vulnerabilities over time (Aikman et al. 2019). To address this issue, scholars advocate that central banks should have explicit financial stability objectives and employ macroprudential policy as an instrument to achieve this goal (Agenor and Da Silva 2019), while monetary policy should continue to focus on price stability. In alignment with this perspective, inflation-targeting economies such as South Africa have adopted explicit financial stability mandates and put in place macroprudential policy frameworks post-GFC to safeguard this objective (Jeanneau 2014). South Africa instituted its financial stability mandate in 2016. To mitigate potential conflicts with the price stability objective, the Prudential Authority (PA) was established to oversee the implementation of macroprudential policy. Furthermore, the Financial System Council of Regulators was established in 2016 to facilitate coordination between monetary and macroprudential policy authorities in South Africa.

While the adoption of macroprudential policy offers advantages in terms of enhancing financial stability, studies and central banks have underscored a policy trade-off between monetary and macroprudential policies, impacting both price and financial stability (Guibourg et al. 2015). The trade-off exists because curbing inflation necessitates tighter interest rates, which in turn can transform debt into higher default rates, thereby exacerbating financial risk. Moreover, a tighter policy rate that achieves low and stable prices may stimulate risk-taking behaviour among agents, as it influences their optimistic economic expectations, thereby leading to exuberant financial behaviour (Nier and Kang 2016; Kim and Mehrotra 2017b). Similarly, stringent macroprudential policy measures increase the cost of credit (Ozkan and Unsal 2014) and constrain its growth below desirable levels, potentially generating macroeconomic instabilities. High credit costs can induce agents to defer spending in the current period, thereby suppressing aggregate demand, which in turn leads to deflationary pressures (Aikman et al. 2019; Sánchez and Röhn 2016). Consequently, it is imperative to understand and quantify the interactions and mutual effects of these policies on each other’s objectives to enable ITs like South Africa to achieve both price and financial stability successfully.

While economic theory indicates that monetary policy influences financial stability and macroprudential policy impacts price stability, there is limited empirical understanding, especially in Africa, of how these policies interact and jointly affect price and financial stability. The literature presents several gaps contributing to this lack of clarity. First, much of the research on monetary and macroprudential policies has centred on advanced economies, focusing on specific financial sectors rather than on broader macroeconomic outcomes such as output, price levels, and the overall financial system (e.g., Nier and Kang 2016; Cerutti et al. 2016; Suh 2012). Other studies like those by Kim and Mehrotra (2016, 2017b), Bussière et al. (2021), and Araujo et al. (2024) have examined macroprudential policy through a cross-country analysis, which often overlooks the unique dynamics in single African countries like South Africa. Second, although research has explored the impact of monetary policy on price and financial stability in advanced economies (e.g., Gerdrup et al. 2017; Garcia-Cicco et al. 2017; Ajello et al. 2016; Wright et al. 2015), it frequently fails to account for macroprudential tools. Given the potential for interactions between monetary and macroprudential policies, it is essential to study both policies within an integrated framework to understand their combined influence on key economic variables.

Third, research in South Africa, such as by Patroba (2017), Liu and Molise (2020), Molise (2020), Nyati et al. (2023), and De Villiers et al. (2024) often focuses on specific financial variables without incorporating the broader financial cycle. These studies also tend to examine individual prudential tools rather than the overall impact of macroprudential policy. While they find that macroprudential measures can mitigate financial shocks, they suggest that coordination with monetary policy is crucial, particularly during crises. This suggestion to coordinate monetary and macroprudential policy further merits an investigation of how these policies interact. The above gaps in the literature leave us with critical questions: Does monetary policy respond to financial developments in African economies? How does macroprudential policy adjust to shifts in price, output, and monetary policy? What are the combined impacts of these policies on output, prices, and financial stability? Finally, how strong or weak are these effects in African economies? Understanding these interactions is key to determining whether monetary and macroprudential policies should be implemented separately or in conjunction.

Against this backdrop, this paper investigates the real and financial effects of the interaction between monetary and macroprudential policies in South Africa from 1980 to 2023, using a Structural Vector Autoregressive (SVAR) model. South Africa provides a unique case study, having developed one of the most advanced macroprudential policy frameworks in Africa. Since 1997, South Africa has used a range of macroprudential tools, including currency exposure limits, capital adequacy ratios, and more recently, countercyclical capital buffers and conservation capital buffers (2016–2024). As a leading economy in this field, South Africa offers valuable lessons for other African countries as they develop their own frameworks. This study contributes to the literature by analyzing monetary and macroprudential policies within a unified SVAR framework, focusing on an African economy. Additionally, this study departs from previous research by incorporating the financial cycle to represent the overall financial system and utilizes a macroprudential policy index to capture the system-wide effects of this policy. The result of the present study indicates that both monetary and macroprudential policy affects output, the price level, and the financial cycle. This indicates that in the case of South Africa, these policies should be used in conjunction. The results also indicate that there is a policy trade-off where macroprudential policy instigates high prices and monetary policy depresses activity of the financial cycle.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows: The next section reviews the literature, followed by a presentation of the data and methodology. The results are then discussed, and this study concludes with final insights.

2. Literature Review

The success of monetary and macroprudential policies in safeguarding price and financial stability depends upon the interactions of these policies (Galati and Moessner 2013). Furthermore, the success of monetary and macroprudential policies is determined by the transmission mechanism of these policies (Agenor and Da Silva 2019). The effects and transmission mechanism of monetary policy are widely known and documented in the literature (see Gali 1999; Sims 1992; Gerdrup et al. 2017; Mishkin 2011a; and Woodford 2008), while the literature on the effects and transmission mechanism of macroprudential policy, and the interactions of monetary and macroprudential policy, is still in its infancy stages. This section reviews the conceptual framework for analyzing interactions between monetary and macroprudential policies. The section also discusses the effects and the transmission mechanism of macroprudential policy.

2.1. Theoretical Review

2.1.1. Complementarity and Substitutability of Monetary and Macroprudential Policies

The relationship between monetary and macroprudential policies has become a topic of significant interest for academics and policymakers, especially following the GFC in 2007–2009 (Aikman et al. 2019; Gelain and Ilbas 2017; Agur and Demertzis 2019; Agénor and Flamini 2016; Liu and Molise 2020). These two policies, while addressing distinct objectives, are increasingly seen as interconnected, influencing each other’s effectiveness and roles in achieving both price and financial stability.

Macroprudential policy refers to the use of prudential tools on a macro-level, aiming to curb the formation of credit and asset price bubbles, manage financial vulnerabilities, and ensure the resilience of the entire financial system (Carreras et al. 2016; Galati and Moessner 2013). These tools are divided into those addressing structural risks and those concerned with cyclical risks (Aikman et al. 2019). Examples of such tools include countercyclical capital buffers (CCyB), loan-to-value (LTV) ratios, and capital adequacy requirements which addresses cyclical risk (Carreras et al. 2016). Others include limits on interbank exposures which addresses structural risk. Monetary policy refers to the deliberate actions by central banks to control inflation and stabilize the currency by regulating interest rates and the money supply (Mathai 2009). In essence, monetary policy’s primary goal is price stability, whereas macroprudential policy focuses on financial stability.

Before the GFC, both monetary and prudential tools were in use, but their roles—especially that of prudential tools—underwent significant refocusing after the GFC. The GFC exposed serious deficiencies in the ability of monetary policy to manage both price and financial stability simultaneously (Verona et al. 2017; Cecchetti and Kohler 2012). Prior to the 2007–2009 GFC, monetary policy was central to macroeconomic management, with a distinct focus on price stability, typically defined as low and stable inflation (Agenor and Da Silva 2019). The monetary policy framework also evolved toward explicit inflation targeting and this framework has an implicit influence on financial conditions (Mishkin 2011a). During the period of the Great Moderation, which saw low interest rates and inflation, this framework was supported by reductions in macroeconomic volatility (Agenor and Da Silva 2019). While some consideration was given to boom–bust cycles in credit and asset prices before the GFC, these were not explicitly incorporated into monetary policy (Ma and Zhang 2016). Consequently, central banks had no explicit financial stability mandates and lacked the necessary tools to address financial disruptions (Aikman et al. 2019).

This limited view of monetary policy was challenged by scholars who advocated for a shift from focusing solely on price stability to a broader mandate. These scholars argued that monetary policy should “lean against the wind” of financial imbalances rather than simply “mop up” after a crisis (Cecchetti et al. 2000; Kontonikas and Ioannidis 2005; Wadhwani 2008; Mishkin 2011b). They suggested that price stability alone, without addressing financial stability, could foster excessive optimism about future economic prospects, encouraging economic agents to take on excessive risk (Cecchetti et al. 2000). Moreover, low and stable inflation without financial stability could fuel asset price bubbles and amplify financial instability (Agenor and Da Silva 2019). This perspective implied that monetary policy frameworks should explicitly incorporate financial developments. However, many still believed that monetary policy should remain focused on price and output stability, leaving financial stability to be managed by other tools (Gelain and Ilbas 2017). As a result, before the GFC, prudential policies were largely discretionary for firms and banks, leaving economies vulnerable to financial disruptions (Galati and Moessner 2013).

The GFC highlighted the failure of price stability to guarantee financial stability, even in periods of low inflation, and strengthened the argument for monetary policy to address financial imbalances. This experience sparked renewed interest in the use of financial regulation to address systemic risks through macroprudential policy (Liu and Molise 2020; Gerdrup et al. 2017; Ozkan and Unsal 2014). In response, inflation-targeting economies like South Africa introduced explicit financial stability mandates alongside price stability goals, supported by macroprudential policy frameworks (Jeanneau 2014).

A central question emerging from these developments is whether monetary and macroprudential policies are complementary or act as substitutes in achieving both price and financial stability. Since both policies influence each other’s transmission mechanisms, understanding their relationship is crucial for effective policy design. Macroprudential policies can affect price stability through their impact on the business cycle, while monetary policy can influence financial stability by affecting credit conditions (Agénor and Flamini 2016). Empirical studies suggest that tightening monetary policy may reduce the quality of borrowers’ credit, increasing default rates and potentially triggering a financial crisis (Nier and Kang 2016). Conversely, an expansionary monetary policy may lead to higher debt levels and asset price bubbles, which macroprudential policy must counteract (Nier and Kang 2016). Tightening macroprudential policy, while increasing the financial system’s resilience, can also reduce output and create deflationary pressures (Kim and Mehrotra 2017b). These findings suggest that achieving the objectives of one policy can frustrate the achievement of the goals of the other.

The question of whether monetary and macroprudential policies are complements or substitutes has important implications for how policymakers should coordinate these policies. If the policies are complements, they should be employed simultaneously and in coordination. However, if they are substitutes, either policy could be used independently to achieve both price and financial stability (Aikman et al. 2019; Ajello et al. 2016; Fahr and Fell 2017). There are divergent arguments on how best to combine these policies (Nier and Kang 2016; Silvo 2016; Claessens and Ghosh 2016).

The first views both policies as countercyclical tools for addressing systemic risks, with monetary policy focusing on price and output stability and macroprudential policy concentrating on financial stability (Agenor and Da Silva 2019; Angelini et al. 2011; Glocker and Towbin 2012). Empirical evidence supports this view, demonstrating the effectiveness of macroprudential policies in mitigating credit supply shocks (Wright et al. 2015), the welfare gains from policy coordination (Ozkan and Unsal 2014), and the role of macroprudential policies in minimizing the stabilization losses caused by monetary policy (Claessens and Ghosh 2016; Ozkan and Unsal 2014). Other studies find that incorporating financial developments into monetary policy leads to significant financial stability gains (Collard et al. 2017; Glocker and Towbin 2012; Paoli and Paustian 2017). This body of research advocates for using monetary and macroprudential policies as complementary tools that should be coordinated.

The second branch suggests that monetary and macroprudential policies are substitutes rather than complements. Cecchetti and Kohler (2012) developed a macroeconomic model showing that both policies can equally achieve price and financial stability. Their findings indicate that price stability, achieved through monetary policy, inherently reduces financial volatility, while macroprudential policies, by mitigating financial vulnerabilities, contribute to macroeconomic stability. Aikman et al. (2019) found that interest rates and capital requirements, representing monetary and macroprudential policies, respectively, operate similarly, supporting the view that these policies are substitutes. Ajello et al. (2016) also concluded that monetary and macroprudential policies could be used interchangeably to achieve the same objectives.

The third branch argues that there is no relationship between monetary and macroprudential policies. Svensson (2018) contends that monetary policy should never respond to financial threats, and macroprudential policy should not address price developments. The study suggests that these policies should be conducted independently by separate authorities, as monetary policy alone cannot simultaneously achieve price and financial stability. Moreover, raising interest rates to stabilize inflation can reduce the quality of borrowers’ credit, increasing default risks and compromising financial stability (Nier and Kang 2016).

The diverging perspectives in the literature on the interaction between monetary and macroprudential policies present challenges for policymakers seeking to coordinate these policies effectively. This divergence underscores the need for further research to better understand the relationship between these two policy areas and to identify the most effective ways to combine them for achieving both price and financial stability.

2.1.2. Channels behind the Effectiveness of Macroprudential Policy

It has been argued that macroprudential policy similarly affects its targets as monetary policy through the bank-risk-taking channel (see Galati and Moessner 2018). In line with this, the literature on the monetary policy transmission mechanism can offer insights on macroprudential policy (Galati and Moessner 2018). In this regard, there are three branches of the literature that offer theoretical underpinnings for macroprudential policy. These include the (i) literature on the banking/finance models (see Diamond and Dybvig 1986; and Diamond and Rajan 2001, amongst others); (ii) literature focusing on three-period general equilibrium models (for example, Bhattacharya et al. 2015; Lorenzoni 2008; and Goodhart 2013); and (iii) literature on the infinite-horizon macroeconomics models with financial frictions (for instance, Kiyotaki and Moore 1997; and Bernanke et al. 1994). These studies appear to be promising in offering analytical tools to examine the impact and effectiveness of macroprudential policy (Brunnermeier and Oehmke 2013; Benigno et al. 2013; Galati and Moessner 2013).

The literature on the banking/finance models aims to show how financial developments are endogenously determined in the economy. These studies introduce information frictions, and commitment and incentive problems, and assess their impact on assets and contracts with the aim of establishing how financial asymmetries lead to default (e.g., Diamond and Rajan 2001). In this regard, Perotti and Suarez (2011) compare the impact of price-based and quantity-based prudential regulation on systemic risk emanating from the bank’s short-term funding. The study finds that an optimal financial regulation is that which includes a Pigouvian tax on short funding, a stable net funding ratio, and a liquidity coverage ratio. Furthermore, this optimal combination has substantial gains in terms of harmonizing financial contracts, which limits defaults (Perotti and Suarez 2011). Hence, macroprudential policy can aid policymakers in maintaining a stable financial system by reducing information asymmetry between lenders and borrowers. Nevertheless, and as argued by Galati and Moessner (2018), this literature has a shortcoming. In particular, it mostly focuses on partial equilibrium; hence, it does not account for feedback mechanisms between the actions of economic/financial agents. To understand the feedback mechanism between the effects of financial agents, a general equilibrium approach is needed (see Kashyap et al. 2014).

The issue of the feedback mechanism is addressed, however, in the literature developing three-period equilibrium models. These studies study the interaction between the influence of the deviation of asset prices from their long-term trend on financial distress (see Goodhart 2013; Bhattacharya et al. 2015; Lorenzoni 2008; and Gersbach and Rochet 2012). In these studies, the fragility of the financial system is contingent on the risk-taking behaviour of heterogeneous agents in the economy (Galati and Moessner 2018). For instance, Goodhart (2013) show that there may be financial amplification during booms and bursts that can spill over to the broader economy. Economic agents do not internalize the consequences of their actions, for instance, the effects that excessive borrowing on asset prices have on fire sales (Gersbach and Rochet 2012). This feedback loop can generate a massive asset price burst, weakens financial constraints, and stimulates fire sales and credit crunches (Carreras et al. 2016). This literature, then, suggests that macroprudential policy can have a significant role in preventing fire sales and credit crunches (Goodhart 2013).

A related type of the three-period general equilibrium literature focuses on the different roles that banks play in the economy and how macroprudential regulation can influence the behaviour of banks. In particular, these roles include providing insurance for savers, improving the risk-sharing opportunities for savers, and increasing the amount of funding available to borrowers, for example, Kashyap et al. (2014). A critical paper in this regard is by Horvath and Wagner (2017). They show that countercyclical bank regulation rescues banks from sector-wide fluctuations, however, at the expense of exposing banks to idiosyncratic shocks. This novel finding implies that there is a trade-off between macroprudential policy geared towards the time dimension of systemic risk and those concerned with the cross-sectional dimension of systemic risk (Carreras et al. 2016). Hence, policymakers should always search for an optimal combination of macroprudential policy if these tools are to be successful. Notwithstanding the contributions of this literature, this literature is highly stylized; hence, it is limited to the analytical tools it can offer for macroprudential policy (Galati and Moessner 2018). Furthermore, it is challenging to incorporate the procyclicality underlying the booms and bursts of the financial system in the three-period general equilibrium framework (Galati and Moessner 2018).

A more promising branch of the literature is that which focuses on infinite-horizon dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models (e.g., Curdia and Woodford 2010; Goodfriend and McCallum 2007). These studies advance from the accelerator mechanism developed by Kiyotaki and Moore (1997) and Bernanke (1999); hence, they have the potential to guide the conduct of countercyclical macroprudential policy. Their unique contribution is that they can introduce financial frictions related to financial intermediaries in their frameworks, thereby offering significant insight on macro-financial dynamics. For instance, Paries et al. (2011) add financially constrained households and firms that are subject to defaults and LTV in their framework. On the other hand, Gertler and Karadi (2011) and Gertler et al. (2012) investigate how the procyclical movement in the bank balance sheet endogenously affects the cost of bank credit. Gertler and Kiyotaki (2015) take a step further and assess how balance sheet conditions affect bank runs in addition to bank credit. The authors complement the financial accelerator mechanism by introducing banks in their model. The study finds that agents face binding constraints, which makes their actions state-dependent (see Gertler et al. 2016, for instance). Using the above framework, Aoki (2021) investigate the macroeconomic impact of bank capital requirements and a tax on foreign currency borrowing. The study find that these instruments have significant effects on welfare.

Some of the literature focuses directly on the issue of endogenous, occasionally binding constraints to borrowers and firms; examples are Bianchi and Mendoza (2010); Jeanne and Korinek (2019); Benigno et al. (2013); Brunnermeier and Sannikov (2014); and Adrian and Boyarchenko (2012). These studies explain how the interaction between falling asset prices, declining net worth, strict financial constraints, and macroeconomic contraction influences the risk of a financial crisis; hence, these studies are also useful in offering macroprudential policy with insight on how risk is determined. A common finding in these studies is that the financial system is inherently unstable. For instance, Brunnermeier and Sannikov (2014) show that financial intermediaries do not internalize the costs of their risk-taking behaviour, thereby resulting in excessive leverage and maturity mismatches. Benes et al. (2014) find that there are non-linear feedback effects between bank balance sheets and borrower balance sheets, which work to exacerbate a financial crisis.

The treatment of financial risk by infinite-horizon DSGE models as endogenously determined puts them in a better position to provide insights about how macroprudential policy works (Galati and Moessner 2018). These models suggest that macroprudential policy ought to be endogenously determined not to come as an exogenous shock. Indeed, Kim and Mehrotra (2017b) show that macroprudential policy is highly effective in curbing excessive credit growth when policymakers take macroprudential policy action after observing financial conditions. Furthermore, when macroeconomic factors such as output and the price levels are analyzed by policymakers before setting macroprudential policy, they tend to improve the effectiveness of macroprudential policy (Angelini et al. 2014). This is also in line with monetary policy, which is typically set after observing the current and lagged values of macroeconomic variables.

2.2. Empirical Review

Evidence on the effectiveness of macroprudential policy has been largely observed amongst emerging market economies, which are the frequent users of macroprudential tools compared to advanced economies (see Shim et al. 2013; Cerutti et al. 2016). In this regard, a substantial number of studies highlight the effectiveness of various macroprudential tools in these economies. For instance, Lim et al. (2013) investigate 49 emerging market economies, which have employed prudential tools such as the LTV cap, the debt-to-income ratio (DTI) cap, ceilings on credit or credit growth, reserve requirements, countercyclical capital requirements, and time-varying/dynamic provisioning. The study finds that these tools are substantially useful in smoothing out significant swings in credit and leverage. Ncube et al. (2023) explored the effectiveness of macroprudential policy in Zimbabwe, a country with a history of hyperinflation and financial instability. They found that macroprudential measures, such as capital controls and reserve requirements, were effective in stabilizing the financial system when coordinated with monetary policy. However, the lack of institutional capacity and regulatory compliance posed significant challenges. In South Africa, Smit and Hollander (2022) examined the role of macroprudential policy in managing systemic risk, focusing on the post-global financial crisis period. They found that while measures such as the implementation of a macroprudential policy index were effective in reducing financial volatility, the lack of coordination with fiscal policy limited their overall effectiveness. The Brzoza-Brzezina et al. (2015) investigates if there is an asymmetry in the impact of these instruments. In particular, the study compares the effects of macroprudential tightening with macroprudential loosening. The study finds that capital requirements affect the credit market, whereas the LTV caps are negatively associated with house prices. This finding is similar to Nier and Kang (2016), who found that DTI and LTV caps have a mitigating effect on credit and housing markets. This implies that the LTV and DTI are useful tools for curbing excessive credit growth.

Some studies have focused on specific regions amongst EMEs. For instance, in Latin America, dynamic provisions have been studied extensively. Dynamic provisions represent an accounting framework which addresses past due payments and expected losses over the business cycle, smoothing provisions throughout the cycle. Alongside dynamic provisions, capital reserve requirements have also been examined. Notable studies include work by Brei and Moreno (2019), Montoro and Moreno (2011), Tovar Mora et al. (2012), Rossini et al. (2019), and Cordella et al. (2014), among others. A common finding in these studies is that these instruments are effective in injecting liquidity back into the economy following a financial crisis. Cordella et al. (2014) note that in the context of Latin America, capital reserve requirements out-perform the policy rates in restoring order to the financial system. Similarly, Pérez-Forero and Vega (2014) find that reserve requirements and dynamic provisions are highly useful in curbing down excessive credit growth. Ampudia et al. (2021) evaluated the impact of macroprudential policies in Latin America using credit registry data and found that the CCyB and dynamic provisioning were effective in stabilizing credit cycles in countries like Brazil and Mexico. However, their impact was mitigated by high levels of dollarization and the presence of shadow banking systems, highlighting the importance of addressing structural vulnerabilities in these economies. Similarly, a study on Colombia by Carreri and Martinez (2022) revealed that the implementation of sectoral capital requirements significantly reduced credit growth in high-risk sectors such as real estate and consumer lending. The study underscored the importance of targeted macroprudential interventions in managing sectoral risks in emerging markets. As a result, these tools have a dual role. This is (i) to restore the economy following a financial disruption; and (ii) to prevent the emergence of financial risk associated with credit growth (see Rossini et al. 2019).

Another frequent user of macroprudential policy has been the Asia economies (see Bruno et al. 2017). In line with this, the Asian economies have been treated as a benchmark for the use of macroprudential policy (Kim and Mehrotra 2017b). These economies have been successful in maintaining and managing financial stability through the use of macroprudential policy (see Kim and Mehrotra 2016, 2017b; Lee et al. 2016; and Jiang et al. 2019). Bruno et al. (2017) assess the impact of macroprudential tools employed by the Asia-Pacific Economies. The study finds that macroprudential policy negatively affects bank and bond inflows. Furthermore, the study finds that macroprudential policy is highly successful when it is complemented by monetary policies. Kim and Mehrotra (2017b) investigate the effects of housing-market-related measures in Australia, Indonesia, Korea, and Thailand. The study finds that tightening macroprudential measures shrinks credit (Kim and Mehrotra 2017b). Cantú et al. (2021) conducted a meta-analysis on the effectiveness of macroprudential policies across the Asia-Pacific region, finding that credit-related tools, such as the LTV cap and the DTI cap, are particularly effective in reducing systemic risk. However, the study emphasized that the effectiveness is contingent on strong institutional frameworks and the degree of financial integration. Similarly, Wijayanti et al. (2021) explored Indonesia’s experience with macroprudential policy and highlighted that combining reserve requirements with the LTV cap was successful in controlling credit growth without stifling economic activity. In China, the rapid expansion of digital finance has posed new challenges for traditional macroprudential tools. A study by Zhang et al. (2018) found that integrating digital financial indicators into macroprudential frameworks helped in better assessing systemic risk and curbing excessive credit growth in the digital lending sector. This suggests that in rapidly evolving financial landscapes, traditional tools need to be adapted to new contexts.

Some of the literature, however, has focused on the effectiveness of macroprudential policy in Europe and the advanced economies. Examples are Turner (2016); Zhang et al. (2018); Agur and Demertzis (2019); Boar et al. (2017); and Richter et al. (2018). A common finding in these studies is that macroprudential policy is distinctively effective in managing financial stability and financial vulnerabilities through its credit channel; however, their effectiveness is superseded by EMEs. Nier and Kang (2016) find that tightening macroprudential policy can raise the cost of credit and contain the build-up of financial risk for 36 advanced economies. By increasing the cost of credit, macroprudential policy lowers bank risk taking, which lowers credit availability, thereby reducing the build-up of financial vulnerabilities. Additional to these effects, tightening macroprudential policy can result in lower asset prices through discouraging the demand for housing as the cost of credit rises. These findings imply that macroprudential policy may be suitable to manage the build-up of financial imbalances that build up over the financial cycle, such as asset price bubbles and excessive credit growth (Borio 2014). Frost et al. (2022) analyzed the impact of macroprudential measures, such as capital buffers and borrower-based measures, across EU countries and found that they effectively mitigated systemic risk, particularly in countries with high private sector indebtedness. However, the study noted that the effectiveness of these measures was sometimes undermined by cross-border regulatory arbitrage. Therefore, macroprudential policy is suitable to manage the financial stability objective. In the European context, the effectiveness of macroprudential policies has been widely studied due to the diverse financial systems and regulatory environments within the EU.

In the United States, macroprudential policies such as stress testing and stringent capital requirements have played a crucial role in strengthening the resilience of the banking sector post-global financial crisis. Laeven et al. (2020) found that these measures were effective in reducing systemic risk and improving financial stability, particularly during periods of economic expansion. However, the study highlighted the need for ongoing adjustments to macroprudential frameworks to address emerging risks, such as those posed by the shadow banking system and fintech innovations. Aikman et al. (2021) focused on the UK’s experience with macroprudential policy, highlighting that measures like limits on LTV and DTI ratios helped curb household indebtedness, particularly in the housing market. The study also emphasized the importance of integrating macroprudential and monetary policies to avoid conflicting policy outcomes.

Biljanovska et al. (2023) conducted a global review of macroprudential policy effectiveness, analyzing data from over 60 countries. They found that while macroprudential policies are generally effective in enhancing financial stability, their impact is highly dependent on the quality of institutions and the level of financial development. The study emphasized the importance of international coordination, particularly in managing cross-border spillovers and regulatory arbitrage. Similarly, the work of Frost et al. (2022) on capital controls and macroprudential policies in advanced economies highlighted that these measures can be effective in managing volatile capital flows and reducing systemic risk. However, the study stressed the need for greater international cooperation to mitigate the potential negative spillovers of unilateral policy.

The success of macroprudential policy in smoothing financial cycles has raised questions about its effect in mitigating the risk of a financial crisis occurring, which is a primary macro-financial concern (see Cerutti et al. 2016). Dell’Ariccia et al. (2016) uses a regression-based analysis to analyze the effects of DTI caps and LTV limits on financial crisis probability. The study finds that these instruments reduce the boom and burst incidents in credit and lower the likelihood of a crisis. Indeed, a major financial crisis is associated with the booms and busts in credit (see Borio et al. 2014). Hence, these macroprudential instruments aid policymakers by smoothing the booms and bursts out. Likewise, Claessens et al. (2013) find that DTI caps and LTV limits shrink the growth of credit, leverage, non-core, and core liabilities. This is in line with the literature that suggests that extended periods of expansion in credit and leverage can generate significant financial crises; hence, macroprudential policy that dampens these cycles is effective (for instance, Borio et al. 2014). In particular, these studies argue that too much credit or too low credit is not the correct ingredient for financial stability; hence, prudential tools that curb down the growth of credit are regarded as effective and successful. The findings are further corroborated by the work of Zhang and Zoli (2016), who found that macroprudential policy reduces the growth of house prices, which is another source of financial vulnerability.

In addition to managing financial stability, macroprudential policy can also affect the real economy. For example, in the context of the Asian economies, Kim and Mehrotra (2017a) argue that a strict macroprudential policy stance lowers credit availability, causing the output to shrink and prices to fall. By reducing credit, macroprudential policy postpones spending, which lowers aggregate demand. This will ultimately lead to deflationary pressures. Therefore, it can be said that output plays the role of channelling macroprudential policy shocks to the price level. In terms of empirical evidence, Aikman et al. (2019), studying the United Kingdom, found that tightening macroprudential policy dampens industrial output, which slows down inflation. Other studies seem to suggest that macroprudential policy can spur on or tame economic growth, which also has significant ramifications for inflation. For example, Sánchez and Röhn (2016), in the context of OECD countries, found that macroprudential policy causes long-term economic growth. These findings suggest that unless macroprudential policy is sensitive to the objectives of monetary policy, its implementation may result in poor performance for monetary policy (Gelain and Ilbas 2017). Put differently, macroprudential policy, in addition to achieving financial stability, can contribute to the achievement of price stability.

It is worth noting how the success of macroprudential policy is contingent on macroprudential policy institutions. In this regard, the literature has yet to find common ground on which institutional arrangement works better for macroprudential policy. For instance, according to Darbar and Wu (2016), adequate institutional arrangements should be judged based on (i) the degree of institutional arrangements in place; (i) the degree of institutional integration between the central bank and prudential authorities; (ii) the role of the government (treasure); (iv) the degree of organizational separation of decision-making and control over instruments; and (v) the existence of a coordinating body for macroprudential policy. Lim et al. (2013), using data for 39 economies, find that a macroprudential policy institutional arrangement that gives the central bank an important role is associated with more timely use of macroprudential policy tools. A similar finding is reached by Nier et al. (2011). These findings are in contrast to Euda and Valencia (2014). The latter study finds that when the central banks react to both price and financial developments, it creates an inconsistency for monetary policy. According to these authors, monetary policy may be abused to reduce the private sector’s real debt burden after a financial shock materializes. Hence, there is no agreed-upon framework for macroprudential policy. Indeed, Darbar and Wu (2016) further propose that macroprudential institutional arrangements should be set up in line with each country’s needs.

The present study makes several key contributions to the existing literature. First, while most studies in this area are panel studies, this research focuses on a single country: South Africa. The challenge with examining a group of countries is the difficulty in separating common macroprudential policy effects from country-specific effects, which can lead to spurious conclusions about the interactions of monetary and macroprudential policies. By focusing on a single country, this study avoids such challenges and provides more precise insights into the interactions of monetary and macroprudential policy. Second, this study examines monetary and macroprudential policies within a unified framework, bridging the gap between studies that focus on macroprudential policy (Lim et al. 2013; Cordella et al. 2014; Galati and Moessner 2018) and those that focus on monetary policy (Ngalawa and Viegi 2011; Galí 2007; Sims 1992; Gerdrup et al. 2017; Gertler et al. 2016; Mishkin 2011a; Woodford 2008). This comprehensive approach allows for a more integrated analysis of the policies’ effects on the financial system. Third, unlike previous studies that focus on specific markets, this study examines the overall financial system, measured by the financial cycle. This broader perspective enables this study to highlight the effects of monetary and macroprudential policies on the entire financial system, offering a more holistic understanding of their impact.

3. Methodology

The effects of monetary and macroprudential policies are crucial to the management of price and financial stability. If the effects of these resemble each other, then policymakers need to be cautious not to put excessive policy pressure in the same direction when they employ both monetary and macroprudential policies. However, if the effects of monetary and macroprudential policies differ from each other, it implies that these policies are pulling in opposite directions, thereby creating a trade-off between price and financial stability. This paper evaluates the real and financial effects of monetary policy and macroprudential policy in South Africa. Existing studies have mainly used reduced panel models to archive this task (for instance, see Kang et al. 2017; Shim et al. 2013; Cerutti et al. 2016; Turner 2016; Zhang et al. 2018; Agur and Demertzis 2019; Boar et al. 2017; and Richter et al. 2018). The challenge with reduced-form panel models is that they do not account for endogeneity between monetary and macroprudential policy (Galati and Moessner 2018). Often, a lag of monetary and macroprudential policy is included to account for endogeneity; however, this is still sub-optimal as there are models that directly account for endogeneity. Moreover, reduced panel models do not account for shocks, responses, and variance decomposition. To bridge these gaps, this study utilizes a Structural Vector Autoregression (SVAR) to identify the effects of monetary policy and macroprudential policy.

The SVAR is chosen because SVAR models have been extensively used in both closed and open economies to evaluate policy transmission mechanisms in a unified framework (see Sims 1992; Christiano et al. 1996; Sims and Zha 2006; and Cushman and Zha 1997, among others). For example, Kim and Mehrotra (2017b) utilize the SVAR technique to evaluate the effects of monetary policy and macroprudential policy’s interaction in four inflation-targeting economies, namely Australia, Indonesia, Korea, and Thailand. The main advantages of the SVAR are that, first, the necessary restrictions of the estimated reduced-form model are provided by theory. As a result, once the identification scheme has been employed, structural shocks can be recovered. Second, in the SVAR, every variable is endogenous as a result of every variable affecting each other (Sims and Zha 2006). This feature of the model allows this study to evaluate the responses of monetary and macroprudential policy to each other’s shocks.

Consider the following structural equation:

where and are matrix polynomials in the lag operator is a vector of independent variables, is an vector of endogenous variables in period , and is the vector of structural shocks such that

The diagonal elements in the VCV () are variances while the off-diagonals are covariances. The structural VAR cannot be estimated directly because of the contemporaneous relations in matrix . Assuming that is invertible, a reduced-form VAR is estimated; afterward, an identification scheme discussed below is imposed on the reduced-form VAR to recover the true structure of the economy. Equation (1) is multiplied by the inverse of to obtain the reduced-form VAR:

where F is the matrix polynomial of parameters and is the reduced-form residuals. To recover the structure of the economy and structural shocks, restrictions are imposed on and matrices. There exist numerous identification schemes, such as the structural factorization, which is based on relevant economic theory, that are usually employed (see Ngalawa and Viegi 2011; Bernanke and Mihov 1998; Sims 1986; and Bernanke 1986). Other scholars employ a zero-long-run identification strategy known as the Blanchard–Quah (Blanchard and Quah 1989; Gali 1999). Blanchard and Quah (1989) argue that imposing long-run restrictions offers more valid results since economic theory is generally concerned about the long run compared to the short run. Another approach is to use Sims (1989) recursive factorization based on the Cholesky decomposition of the matrix. This identification scheme requires that the most endogenous variables be ordered last (Favero 2001). This approach is widely used in the literature (see Sims 1986; Kim and Mehrotra 2017a; and Christiano et al. 1996, for example).

This study follows Kim and Mehrotra (2017b) by imposing a recursive factorization/Cholesky decomposition on Equation (3) to obtain the structural shocks. This study consists of three target variables, namely the real GDP (Y), consumer price index (P), and financial cycle (FC); two policy instruments are included, namely the macroprudential policy index (MPI) and policy rate (PR). Furthermore, two exogenous variables are used: the US policy rate (USPR) and oil prices (USOIL). Table 1 below provides a list and details of all variables used in this study. The latter variable, oil prices, as suggested by Sims (1992), is included to possibly address the ‘price puzzle’. The variables Y and P are targets for monetary policy. The variable FC represents the target for macroprudential policy. This is consistent with Nier and Kang (2016). The MPI is chosen because it captures the number of times macroprudential policy tools are used within a specific timeframe. It also captures the direction (i.e., tightening or easing) of the use of macroprudential policy tools. In its original form, the MPI is a dummy variable. This study follows the rolling window procedure favoured by Kim and Mehrotra (2017b) to transform the MPI into a time series. Accordingly, when macroprudential policy tightening occurs, the index increases by one unit regardless of the type of tool used, or its intensity. Likewise, when macroprudential easing occurs, the index decreases by one unit regardless of the type of tool used or its intensity. The new value of the index is maintained until another policy action is taken. If two tightening measures occur during the same quarter and none in the direction of loosening, the index level increases by two units during the same quarter. Other scholars, such as Bruno et al. (2017) and Zdzienicka et al. (2015) have favoured this approach of accumulating the index. This study’s version of the MPI is different from that of Cerutti et al. (2016), who capture the introduction of or removal of various policy measures in their index, but they do not take into consideration changes in the levels of individual policy tools over time.

Table 1.

Data definition and sources.

The financial cycle was constructed by the authors for the purpose of this study. The FC reflects the evolution of systemic risk over time in the financial system. This study follows Brave and Butters (2011) and constructs the FC by extracting a common factor of financial variables using a principal component analysis (PCA). Thereafter, the Baxter–King filter was utilized to detrend the financial cycle. De Wet and Botha (2022) and Kabundi and Mbelu (2021) also used PCA to construct versions of the South African FC. The following financial variables are used to construct the FC: the balance of payments (BOP), credit-to-GDP ratio (CRG), residential property prices (P.P.), real effective exchange rate (F.X.), aggregate index of equity prices (E.Q.), growth rate of GDP (Y), net international investment position (IIP), long-term interest rates (LRI), and aggregate money supply (M3). These variables were selected as they represent the various segments of the South African financial system.

Moreover, these variables have been favoured by other existing studies as the crucial ingredients in the composition of the FC (see Brave and Butters 2011; Kabundi and Mbelu 2021; Drehmann et al. 2012; Claessens et al. 2011; and Nyati et al. 2023). This is because the movement of these variables and their correlation correspond to most developments in systemic risk over time. The variables CRG, P.P., F.X., and E.Q. were collected from the Bank of International Settlements’ statistics. The variables BOP and IIP were collected from the International Monetary Fund’s International Financial Statistics. The variable GDP was collected from the SARB. The BOP captures S.A.’s fiscal position. The variables CRG, P.P., and E.Q. represent developments in the credit and asset markets. These variables are also considered to be the best indicators of systemic risk. Their cyclical fluctuations occur around episodes of financial distress (Borio 2014). The F.X. captures the exchange rate market, whereas M3 represents the monetary sector. In this study, no weights are attached to variables entering the PCA, allowing each market to affect South Africa’s financial conditions equally. This is consistent with De Wet and Botha, who found that these variables strongly impacted the FC above 0.75 percent in absolute terms.

In line with existing studies such as Kim and Mehrotra (2017b), output, prices, and credit enter the system with contemporaneous relations to both MPI and PR to allow policy stances to be taken after observing the state of the economy (see Quint and Rabanal 2013; and Christiano et al. 1996). The identification scheme presented above is summarized in (4) below, where is a lower triangular matrix, and is a diagonal matrix.

The first 2 rows imply that the South African economy is small enough not to influence oil prices and federal fund rates (Kganyago 2012; Nzimande and Msomi 2016). Y, the CPI, and FC are affected by exogenous shocks. However, they are slow in responding to policy shocks. According to Ngalawa and Viegi (2011), real economic activity is likely to respond to lags of policy shocks because people are generally tense to changes, and it takes time to make plans to match the new policy stances. On the other hand, output and prices respond to financial shocks. The financial sector in EMEs is used to finance spending on the household sides and to finance investments on the firms’ side, leading to immediate responses in output and prices (Agenor and Da Silva 2019). The MPI and PR are endogenous to all the variables in the system.

4. Results

This section presents and discusses the findings of this study. Firstly, the results of the unit root tests are presented and discussed. The unit root tests are conducted using the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and the Philip–Peron (PP) tests. The ADF and PP both test the null hypothesis that the series has unit roots against the alternative hypothesis that the series has no unit roots. The findings of these tests are reported in Table 2. The significance of values in the ADF and PP tests suggests that the null hypothesis of unit roots is rejected. All coefficients in the table are significant except for the price level and the financial cycle. Therefore, the study rejects the null hypothesis of unit roots for variables except for P and FC and concludes that all variables are stationary except for prices and the financial cycle.

Table 2.

Unit roots—Output, price level, financial cycle, policy rate, and macroprudential index.

Despite the finding of unit roots in some variables, the model, SVAR, is estimated without transforming the data. This follows Ngalawa and Viegi (2011). They argued that non-stationarity of the variables in the system does not adversely affect the results. Hence, there is no need to transform the data. This is also argued by Sims (1992). The author posit that imposing many restrictions and transformations on data may lead to spurious results.

To ensure that an optimum number of lags is selected, this study uses the Akaike Information Criteria, Schwarz Information Criterion (SIC), and Hannan–Quinn Information Criterion (HQ). The results are displayed in Table 3. The Akaike Information Criterion suggests the lag length of order two, in line with the Schwarz Information Criterion and the Hannan–Quinn Information Criterion tests, which also suggest a lag length of order 2. Given that the SIC, HQ, and AIC are congruent, this study chooses a lag length of 2.

Table 3.

Lag ordering.

Next, we present the SVAR results. Before delving into the main findings, we first address the autocorrelation results. According to economic theory, the residuals from the SVAR model should be independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.). This non-autocorrelation is essential for accurate parameter estimation, model validity, and prediction reliability. To test this, we employed the Lagrange Multiplier Autocorrelation test (LM test) developed by Godfrey (1978). The null hypothesis of the LM test is that the error terms in one period are influenced by those in the previous period. The results are shown in Table 4. The probability values associated with the LRE statistics and Rao F-statistics indicate that we reject the null hypothesis at lags 1, 2, and 3. This suggests that structural shocks in one variable during the current period are independent of those in the prior period. This crucial finding demonstrates that there is no evidence of autocorrelation in our SVAR model, confirming its validity and the accuracy of the estimated coefficients.

Table 4.

Autocorrelation LM test.

Next, a correlation analysis of structural shocks is reported in Table 5. The table suggests a positive relationship between output and prices, which is consistent with the literature (Kim and Mehrotra 2017b; Garcia-Cicco et al. 2017). Furthermore, it is found that between (i) the financial cycle and output, and (ii) the financial cycle and the price level, there is a sanguine relationship, which is consistent with other studies (for example, Oman 2019; Drehmann et al. 2012; Claessens et al. 2011; and Al-Oshaibat and Banikhalid 2019). The findings imply that financial cycle developments can affect output and the price level, which is in contrast to the pre-2007–09 supposition that financial shocks did not matter in the macroeconomy (Drehmann et al. 2012). However, in the case of South Africa, this study finds that financial shocks affect the macroeconomy, thereby motivating for the inclusion of financial developments in monetary policy decisions in South Africa.

Table 5.

Correlation of output, prices, credit, policy rate, and macroprudential index.

In terms of policy shocks, the correlation between the policy rate and the macroprudential policy index is 0.04, implying that monetary policy and macroprudential policy are positively linked. The positive correlation between the policy rate and the macroprudential policy index is similar to findings in other studies (for example, Alpanda and Zubairy 2017; and Bruno et al. 2017). Bruno et al. (2017) found that there is a positive link between macroprudential and monetary policy action. This finding has in-depth ramifications for the conduct of monetary and macroprudential policies. This essential finding implies that there may be endogenous policy responses between monetary and macroprudential policies to offset the effect of policy shocks to price and financial stability objectives. A similar finding was reached by Kim and Mehrotra (2017b).

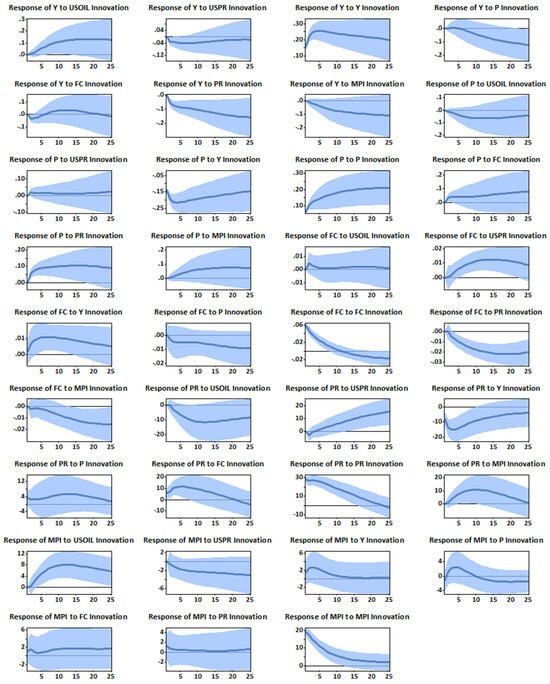

Having performed the correlation analysis, this study turns to the analysis of impulse response functions (IRFs). Figure 1 plots the responses of monetary policy and macroprudential policy alongside the responses of output, the price level, and the financial cycle. All IRFs are represented by the solid blue lines while the shaded blue lines are 95 percent confidence intervals. The x-axis is measured in months and extends to two years while the y-axis is percentage changes. Firstly, this study notes the responses of MPI and PR to exogenous shocks. Shocks to the US policy rate (USPR) and oil prices (USOIL) trigger responses from monetary and macroprudential authorities by the SARB and the PA. Figure 1 shows that after a shock to the US policy rate, both the macroprudential policy index and the policy rate react by falling. The results suggest that the SARB is sensitive to global monetary policy shocks since they may interfere with both price stability and financial stability in SA. Moreover, this confirms the view that the SARB tends to follow the Federal Reserve Bank when deciding the conduct of monetary policy (Kabundi et al. 2020). According to Kabundi et al. (2020) every time the Federal Reserve changes its policy rate, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) tends to follow suit. The Fed tightened earlier in the lead up to the global financial crisis of 2008 and cut earlier immediately following it. Between 2010 and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, the correlation between US and SA monetary policy was weaker, with the effects of South African idiosyncratic events like the 2016 drought clearly visible, for example. SARB’s monetary policy cycles appear to have become more coincident with the US Fed’s since 2020’s COVID-19 pandemic. Since 2000, the correlation between the 3-month lagged fed fund rate and the repo rate is 0.57, suggesting the SARB has tended to follow US monetary policy eventually. Interestingly, the correlation is higher at longer lags, although this should be interpreted with caution as some policy cycles have lasted less than a year.

Figure 1.

Impulse response functions; baseline model.

The responses of MPI and PR to US monetary policy shocks suggest that either macroprudential policy or monetary policy can be used to stabilize the economy after an exogenous US monetary policy shock. In contrast, a shock to the US oil prices triggers a rise in MPI and a fall in PR. That is, the repo rate falls in reaction to a US oil price shock, whereas the macroprudential policy index rises instead. This finding implies that these policies should react in conjunction to oil price shocks in order to bring these polices back into equilibrium. This is consistent with the results of Garcia-Cicco et al. (2017), who also found that monetary and macroprudential policies in Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru react as complements to global commodity price shocks.

Secondly, this study analyzed the responses of macroprudential policy and monetary policy to target variable shocks. All shocks to output, inflation, and the financial cycle trigger monetary and macroprudential policy responses. For example, a shock to output, the price level, and the financial cycle results in a rise in the macroprudential policy index. This suggests that macroprudential policy, in addition to reacting to financial developments, is also affected by developments on the real side of the economy (see Angelini et al. 2014; and Liu and Molise 2020). A macroprudential policy contraction indicates that policymakers are interested in restricting the build of financial imbalances that are contained in financial shocks. These findings are consistent with that of Kim and Mehrotra (2017b). For instance, they found that private credit shocks trigger a contraction of macroprudential policy reaction in the Asia-Pacific region. Furthermore, a contractionary macroprudential policy reaction to output and prices reflects that the Prudential Authority in South Africa must take into account developments in the macroeconomy that have potential to adversely affect the financial sector.

Between 1997 and 2007, during South Africa’s longest financial expansion, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) implemented macroprudential policies to safeguard financial stability and align with Basel standards (Magubane 2024). As part of this effort, the SARB adopted the Basel II framework and introduced several tools to manage financial risks. Beginning on 1 January 1997, prudential limits were set for currency exposure: the cap for major currencies—USD, ZAR, GBP, and EUR—was set at 15% of a bank’s unimpaired capital per currency, while all other currencies had a limit of 5%. The overall foreign currency risk exposure was capped at 30% of a bank’s unimpaired capital. Furthermore, banks were prohibited from exceeding their intraday overall foreign exchange risk position by more than 5% of the overall limit without prior approval from the Bank of Botswana.

In response to growing concerns about credit growth and risk-taking behaviour in the early 2000s, the SARB tightened capital adequacy requirements. For example, in October 1998, the authorities increased the risk weight for new mortgage loans with a loan-to-value (LTV) ratio above 80%. Between 2003 and 2005, the SARB made three significant adjustments to capital adequacy ratios, beginning with Bank Supervision Circular 8/2003, which revised the treatment of preference shares and narrowed the definition of regulatory capital. This was followed by Circular 1/2004, which mandated compliance with Basel II capital requirements, and Circular 19/2004, which stipulated that at least 60% of minimum required capital should consist of primary share capital, excluding hybrid debt instruments. As a result, overall capital adequacy ratios increased from 11.96% in March 2003 to 13.67% in March 2005.

The introduction of Basel III in 2016 further strengthened South Africa’s macroprudential policy framework to mitigate financial vulnerabilities. Key components included the implementation of the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB), capital conservation buffer (CCB), and enhanced capital requirements (CAP). The CCyB, announced on 26 April 2013, and effective 1 January 2016, is applied to all banks and can be adjusted up to a maximum of 2.5%. The CCB, phased in from 2016 to 2019, gradually increased from 0.625% to 2.5%, in line with Basel III guidelines, to ensure that banks build up a capital buffer during periods of credit growth, which can then be used to absorb losses during downturns.

As expected, monetary authorities, following the price level and financial shocks, react by raising policy rates. The monetary policy response to price shocks is an endeavour to arrest the upward pressure on the prices, thereby maintaining a stable price level. A typical example of this is the increase in the repo rate from 3.25 basis points in 2020 to 8.25 basis points in 2024 as a result of inflation rising the upper bound target of 6% during the period. The SARB’s response to financial cycle shocks highlights its consistent focus on financial stability. This is evident in the inclusion of financial variables in the construction of its business cycle indicators, underscoring the central bank’s proactive approach to monitoring and responding to financial developments. In the literature, this focus of monetary policy to financial developments is associated with the ‘lean against the wind’ view on monetary policy and financial stability (see Gerdrup et al. 2017; and Mishkin 2011b). In this view, monetary policy has an active role in containing financial shocks since they may induce higher inflation through their stimulating effects on income and spending, thereby affecting the price stability objective. Indeed, studies, for example, Al-Oshaibat and Banikhalid (2019), suggest that financial expansion causes inflation by financing spending, which increases aggregate demand, and thus the price level. In response to an output shock, authorities respond by lowering the policy rates, suggesting that policymakers are not only concerned about price stability, but they are also concerned with accommodating output. The latter response is likely to occur since monetary authorities have a role to stimulate economic growth (Ngalawa and Viegi 2011). For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the SARB played a crucial role in supporting the economy by easing monetary policy and introducing liquidity measures. To mitigate the economic impact, the SARB initially cut the policy rate by 100 basis points to 5.25% and introduced measures to support banks, including a lower rate for commercial banks to borrow from the central bank. This aimed to alleviate the pressure on banks caused by the pandemic, while also increasing daily repo auctions to twice a day to provide additional liquidity.

In an emergency meeting on 15 April, SARB announced another 100-basis-point rate cut, bringing the policy rate down further. At the same time, it scaled back to one daily repo auction, having successfully injected liquidity into the banking system. On 15 May, SARB reduced the repo rate by an additional 50 basis points, bringing the total rate cuts for 2020 to 275 basis points. These actions were designed to stimulate the economy by lowering borrowing costs and ensuring ample liquidity during the economic downturn caused by the pandemic.

This study further analyzed the responses of output, the price level, and the financial cycle to policy shocks. Figure 1 presents the responses of output, inflation, and the cycle to policy shocks. A shock to macroprudential policy results in higher prices; however, there is a decline in the financial cycle and output. The impact of macroprudential policy on credit has already been established by the literature. For example, Cerutti et al. (2016) found that a shock to macroprudential policy results in a significant statistical shrink in real credit in both advanced economies and emerging economies. Similarly, Nier and Kang (2016) show that tightening the loan-to-value ratio, a macroprudential tool, shrinks credit. The response of the financial cycle to a macroprudential policy shock can explain the impact of macroprudential policy on the price level and output. Firstly, since the financial sector facilitates spending (Kim and Mehrotra 2017a), by lowering the financial cycle macroprudential policy, this reduces spending and shrinks output. Moreover, the adverse macroprudential policy effects on the cycle can be costly in terms of aggregate financing for firms, leading them to retaliate by raising their prices and causing inflation. It is also interesting to note that the upward trend in the price level may be too strong for a macroprudential policy shock in South Africa. Hence, a tighter macroprudential stance may coincide with higher prices.

A monetary policy shock on the other hand results in a fall in output and the financial cycle, but a rise in the price level. The impact of a monetary policy contraction to output and the financial cycle is similar to findings in other studies (see Smets 2014; Gerdrup et al. 2017; and Aikman et al. 2019). However, in this study, it is observed that statistically, the impact of monetary policy is stronger than the impact of macroprudential policy in the financial cycle. According to Figure 1, the response of the financial cycle to MPI is only significant after 15 months, whereas it is significant at all months following a PR shock. Accordingly, macroprudential policy is not sufficient to deliver financial stability in South Africa. This policy must be complemented with monetary policy. The increase in the price level resulting from a monetary policy contraction is known as the ‘price puzzle’ (Ngalawa and Viegi 2011; Sims 1992; Bernanke and Mihov 1997). Several explanations exist for the price puzzle. According to Sims (1992), the price puzzle arises if monetary authorities react to expectations of higher inflation by raising the interest rates but by not enough to actually prevent inflation from rising. Alternatively, the price puzzle may occur if monetary authorities react to supply shocks rather than demand shocks (Sims 1992). Adverse shocks are likely to raise prices and the interest rates. However, if the rise in policy rates is not strong enough to bring down prices, the price puzzle emerges (Sims 1992).

The responses of each target variable to shocks in other target variables was also analyzed. Shocks to the price level trigger financial cycle responses. According to Figure 1, the financial cycle reacts by declining following a price level shock but rises following a shock to output. The results suggest that a high-inflation environment is not conducive for financial stability in South Africa. Likewise, shocks to the financial cycle impact output and prices. Both output and the price level react by rising following a shock to the financial cycle. This finding confirms the procyclicality of the economic system in South Africa. To illustrate, the 2002–2007 credit boom in South Africa was characterized by robust economic growth, fuelled by a significant increase in household credit extension (Hollander and Havemann 2021). During this period, the South African economy expanded at an average annual rate of 4.5%, with consumer price inflation remaining within the target range of 3–6%. The credit boom was primarily driven by increased consumer spending, supported by a surge in credit availability. However, this period of rapid economic growth was also marked by rising household debt levels and concerns about potential financial instability.

Figure 1 also displays some interesting interactions between the macroprudential policy index and policy rate given the interactions between the objectives of these policies. Firstly, in response to a macroprudential policy contraction, the policy rate rises. This response shows the desire of monetary authorities to maintain price stability and output stability following the effects of macroprudential policy on these targets. Studies, for example, Alpanda and Zubairy (2017) and Kim and Mehrotra (2017b), have documented the existence of an endogenous policy response from monetary policy to stabilize the real economy after a macroprudential policy shock. If macroprudential policy depresses output and the price level, monetary policy loosens such as in these studies. However, if macroprudential policy stimulates output expansion and induces inflation, monetary policy contracts such as in this study. Secondly, macroprudential policy shrinks in response to a monetary policy shock. This response can be interpreted as an endogenous macroprudential policy response to the financial cycle after a monetary policy shock. This response occurs if monetary policy pushes credit too low (Angelini et al. 2014). If credit is too low, this may lead to poor economic performance and adversely affect the health of the financial sector.

This study also analyzed the relative importance of each structural shock in explaining fluctuations in the two policies in question and the target variables. To this end, this study turns to the variance decomposition. Table 6 presents the results over a two-year forecast horizon. Given the two objectives of price stability and financial stability, fluctuations in the policy rate dominate the price level compared to the financial cycle. While price shocks account for 3.5 percent of the policy rate fluctuations after six months, 4.1% after a year, and 5.1 percent after two years, FC accounts for 0.4 percent of policy rate fluctuations after six months, 0.2 percent after a year, and 0.9 percent after two years. Macroprudential policy fluctuations on the other hand are dominated by the financial cycle rather than prices. The financial cycle accounts for 0.2 percent of macroprudential policy fluctuations after six months, 1.7 percent after a year, and 4.1 percent after two years. The price level on the other hand accounts for 0.09 percent macroprudential policy fluctuations after six months and 0.1 percent macroprudential policy fluctuations after a year onwards. These findings reflect that the principal objective for macroprudential policy should be financial stability while it should be price stability for monetary policy.

Table 6.

Variance decomposition.

Fluctuations in target variables are dominated by monetary policy rather than macroprudential policy. This suggests that monetary policy can get into all the cracks in the economy compared to macroprudential policy. For example, the policy rate accounts for 32.3 percent of price fluctuations after six months, 34.1 percent after a year, and 33.4 percent after two years. Similarly, the policy rate accounts for 12.2 percent of financial cycle fluctuations after six months, 16.7 percent after a year, and 30.1 percent after two years. Macroprudential policy on the other hand accounts for less than a percentage of price fluctuations throughout the two-year forecast horizon while it accounts for 1.4 percent of financial cycle fluctuations after six months, 2.6 percent after a year, and 5 percent after two years.

Additional exercises were conducted to check the robustness of the main results. This study considers alternative identification in the VAR, namely Blanchard and Quah (1989) decomposition. In contrast to the Cholesky, the Blanchard and Quah (1989) decomposition identifies the long-run effects of both macroprudential and monetary policy. Macroprudential policy is likely to have long-run effects. For example, Boar et al. (2017), in a panel of 64 emerging economies, found that countries that use macroprudential policy experience low volatility per-capita GDP in the long run.

The long-run restrictions this study imposes are identified in the scheme presented in Equation (5) below. The US policy rate, US oil prices, and SA’s monetary and macroprudential policies’ shocks are identified in a similar manner to the Cholesky decompositions in Equation (4), implying that the US variables are not affected by the South African variables, and monetary and macroprudential policies react to all shocks in the system (see Equations (4) and (5)). The third and fourth rows in Equation (5) suggest that the price level and output are sluggish to respond to policy shocks. This restriction is based on the observation that most aggregate real variables such as output and the price level respond with a lag to monetary and macroprudential policy shocks due to inertia and planning delays (Bernanke and Mihov 1997). The fifth equation implies that the financial cycle is contemporaneously affected by all variables in the system. This is in line with Ngalawa and Viegi (2011) who argue that expectations of future economic activity form an important determinant of financial activity today. Given that output, the price level, and monetary and macroprudential policies contain information about future economic activity, the financial cycle may respond contemporaneously to all variables in the system.

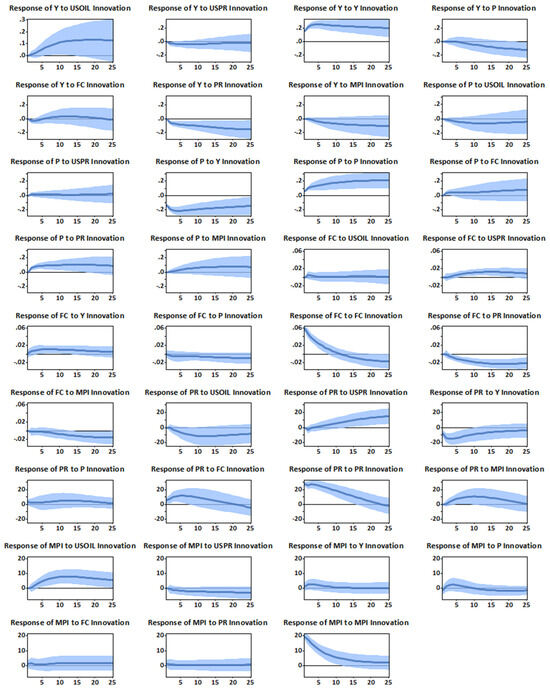

In Figure 2, this study plots the results of the Blanchard and Quah (1989) decomposition. The figure shows that results are robust under alternative identification. Both the impact of macroprudential policy and monetary policy are the same when the identification assumptions are changed from short-run restrictions to long-run effects.

Figure 2.

Impulse response functions; long-run restrictions.

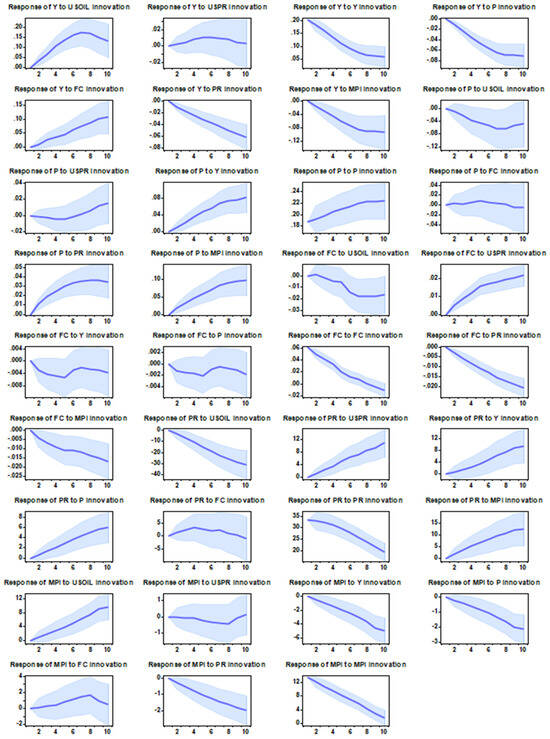

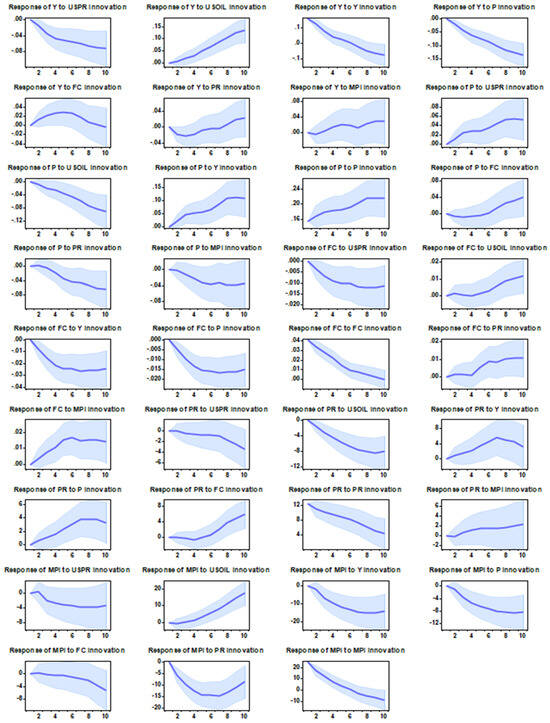

Besides imposing long-run restrictions, this study also analyzed impulse response functions across two sub-periods using the Cholesky restrictions in Equation (4). The first period, from 1980 to 2009, corresponds to a time of low usage of macroprudential policy in South Africa. The second period, from 2010 to 2023, reflects a phase when macroprudential policy began to be used more frequently in the country (Magubane 2024).