Abstract

Over the past four decades, China’s real estate industry has experienced rapid growth, accompanied by frequent regulatory interventions. These shifts present an ideal context for examining the characteristics of private equity placements (PEPs) under varying industrial policy environments. This study examines the PEPs of Chinese real estate firms from 2006 to 2023, calculating the cumulative abnormal returns during announcement periods and the transaction discounts across various regulatory phases. The analysis reveals significant positive announcement effects, even in times of policy tightening, with these effects becoming more pronounced during periods of policy relaxation. However, regression analyses suggest that the policy environment does not significantly impact the announcement effects. Contrary to traditional views, PEP discounts tend to be shallower during policy tightening and deeper during policy loosening. Further analysis indicates that investors are willing to accept smaller discounts in exchange for more valuable investment opportunities.

1. Introduction

Distinct from public offerings, private equity placements (PEPs) involve the issuance of new shares to a selected group of sophisticated investors, such as investment banks or funds (Wruck 1989). PEPs have emerged as a vital refinancing tool across various countries and markets. For instance, Brophy et al. (2004) noted that fundraising through PEPs in the U.S. grew from 8.1 billion USD in 1990 to approximately 154 billion USD by 2000. Similarly, Xu et al. (2017) reported that PEP capital in Australia increased nearly 20-fold between 1995 and 2009. A similar upward trend has also been observed in East Asia (Baek et al. 2006; Kato and Schallheim 1993).

Market reactions to PEPs, in contrast to other types of seasoned equity offerings (SEOs), have garnered considerable scholarly attention. For instance, a meta-analysis by Veld et al. (2020) found that the average cumulative abnormal return (CAR) for SEOs was −0.98%, with a median of −1.39%. However, positive announcement effects have been documented across various markets (Hertzel and Smith 1993; Kato and Schallheim 1993; Wruck 1989; Xu 2010; Zhang 2007). Nevertheless, most existing research has been based on market-wide samples. For example, Wruck (1989), Hertzel and Smith (1993), and Barclay et al. (2007) focused on the U.S. market, while Cronqvist and Nilsson (2004) examined the Swedish market. Studies on the Chinese market include those by Zhang and Li (2008) and Xu (2010).

However, research on PEPs from an industry perspective is relatively sparse. For example, Folta and Janney (2004) investigated the U.S. biotechnology sector, finding that PEPs help to mitigate long-term information asymmetry issues. Lin and Gannon (2007) observed a negative announcement effect in the Australian biotech and healthcare sectors, contrary to the positive price reactions commonly reported. This suggests that industry-specific characteristics may influence the dynamics of PEPs differently.

Existing research has not fully investigated PEPs at the industry level, while the Chinese real estate sector offers a unique and valuable framework for such studies. Over the past forty years, China’s rapid economic development has been largely driven by the real estate sector. Under government intervention, the real estate industry has worked closely with local governments and the traditional banking system to grow into a key engine of China’s economic growth (Xiong 2023). However, this rapid development has also accumulated significant risks. For instance, Fang et al. (2016) highlighted that the imbalance between high housing prices and resident incomes has elevated household debt levels, which may hinder future consumption capacity. Additionally, declining birth rates exacerbate the supply–demand imbalance (Xiong 2023). Xiong further accentuated that, while high leverage in real estate companies is not inherently problematic, it becomes a significant risk in the context of sluggish economic recovery and frequent government interventions. In recent years, the liquidity crises confronted by real estate companies, such as China Evergrande, have been largely attributed to the “Three Red Lines” policy. This policy, introduced by the central government in 2020, imposes strict regulations on the debt ratios of real estate firms (Bohnenkamp and Kammann 2024). This underscores the substantial impact of government policy on the development of enterprises within the sector. No other industry in China has been subject to such sustained public scrutiny and long-term regulatory intervention faced by the real estate sector.

China’s real estate sector does not experience large economic cycles, making it an ideal environment for studying the impact of policy changes. Given its critical role in China’s economy, local government officials often prioritize real estate development as a means to boost local economic growth, which, in turn, affects their career advancement. Consequently, adjusting the real estate policy has become a tool for the central government to regulate economic growth.1 As Xiong (2023) noted, “When the real estate market is under distress, the central government may adjust its macroeconomic and monetary policies and loosen mortgage requirements to support the market, while local governments may take direct measures to prevent real estate prices from falling”. An and Wang (2013) further confirmed that real estate regulatory policies are key determinants of housing prices. These regulatory measures typically include managing land supply, implementing affordable housing policies, and leveraging fiscal and financial tools. These strategies act as crucial mechanisms through which the government exercises control over the real estate market.

As a capital-intensive industry, the real estate sector has a strong demand for financing. Reliance on traditional bank financing increases the debt burden, whereas PEPs can effectively mitigate this issue. Ning and Jalil (2023) argued that PEPs, as a form of equity financing, not only help to reduce the debt ratios of real estate companies, but also alleviate liquidity issues. Song et al. (2024) found that excessively leveraged firms can mitigate their financing constraints through PEPs, thereby enhancing the firms’ value. Moreover, PEPs serve a certification function, helping to ease information asymmetry and improve long-term corporate governance (Hertzel and Smith 1993; Ning and Jalil 2023; Wruck 1989). Therefore, it is of great significance to understand how PEPs combine with industry characteristics to improve the quality of real estate enterprises.

This study aims to explore how industry characteristics influence PEPs, with a particular focus on the impact of the policy environment on sector-specific refinancing activities. Specifically, we seek to determine whether the announcement effects of PEPs in different industry policy environments align with those observed in market-wide studies. Does the market react more positively during periods of policy relaxation compared to periods of tightening? Is the industry policy environment a significant factor in determining transaction pricing?

Typically, shifts in the policy environment can reshape investors’ expectations regarding the outcomes of PEPs. During periods of policy relaxation, more lenient financing conditions and fewer transaction restrictions foster optimism for stronger property sales, prompting firms to aggressively bid for land and expand their projects. Consequently, the market anticipates this increase in supply and demand, leading to more positive reactions. In contrast, during the policy-tightening period, investors become more cautious, adjusting their pricing strategies to account for amplified risks. Nevertheless, they also need to recognize that companies approved by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) under stricter policies are likely to have stronger management and higher-quality assets. As a result, PEP pricing reflects a balance between these risks and quality signals.

Our study reveals that PEPs in Chinese real estate companies exhibit a significant positive announcement effect, even during periods of policy tightening. This positive effect is even more pronounced during periods of policy relaxation. While the policy environment is not a key determinant of PEP announcement effects, it plays a crucial role in PEP pricing. Contrary to traditional views, PEP discounts tend to be shallower during market tightening and deeper during periods of relaxation. We argue that companies successfully executing PEPs are of a higher quality and are capable of standing out even in unfavorable policy environments. Further analysis reveals that transactions involving major shareholders involve lower discounts, and the long-term returns of PEPs are significantly positive, in contrast to the generally negative outcomes reported in other studies. The evidence suggests that investors are willing to accept shallower discounts in exchange for valuable investment opportunities, rather than being deterred by adverse industry policies.

The findings also indicate that market sentiment, proceeds, leverage changes, and management expenses significantly influence the announcement effects of PEPs in real estate companies. A closer examination of leverage changes reveals that the market’s perception of real estate firms’ investment activities varies depending on the industry’s development stage. The market responds positively to proactive management actions, reflecting its encouragement of companies that seize growth opportunities. During periods of policy relaxation, the market tends to focus more on transaction- and firm-specific characteristics, whereas, during periods of tightening, investor sentiment takes precedence.

In addition to the policy environment and major shareholder involvement, the pricing model plays an important role in pricing negotiation. Specifically, during policy-tightening periods, investors not only pay attention to the signals conveyed by major shareholder participation, but also remain cautious about their motives, particularly concerning potential tunneling behaviors. The significant relationship between proceeds, fractions placed, and discount rates supports the certification (information) hypothesis (Hertzel and Smith 1993). Interestingly, there is a positive correlation between ownership balance and discount rates during periods of policy relaxation. This suggests that investors fear that decreased major shareholder control could lead to missed opportunities in a favorable environment, causing them to demand higher discounts as compensation for this uncertainty. Overall, our findings not only support the certification hypothesis, but also highlight how changes in the policy environment and industry characteristics shape PEP transaction dynamics.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a literature review and research hypotheses; Section 3 details the data selection, calculation methods, and variable definitions; Section 4 provides an overview of the real estate policy evolution history and background information of PEPs in China, and then analyses the impact of industry policy environments on announcement effects and discount rates; and Section 5 summarizes the key findings, research limitations, and implications.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Literature Review

Typically, corporate refinancing activities, such as SEOs, often elicit negative market reactions. This is attributed to the belief that informed managers, who possess superior information, tend to issue new shares when they perceive the company’s stock to be overvalued (Myers and Majluf 1984). However, a substantial body of research has documented that PEPs generally exhibit positive announcement effects. Wruck (1989) reported that companies experienced an average wealth gain of approximately 4.5% during the announcement period, and this finding was corroborated by subsequent studies on the U.S. market (Barclay et al. 2007). Similar positive announcement effects have been observed in other markets, including those of Japan, Singapore, and Sweden (Cronqvist and Nilsson 2004; Kato and Schallheim 1993; Tan et al. 2002). In China, this phenomenon has also been documented (Hu and Zhang 2016; Sun 2015; Wu 2016; Zhang and Guo 2009). For example, Zhang (2007) found that the average cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) in the event windows [−10, +5] and [−5, +5] were 8.59% and 7.20%, respectively. Furthermore, studies have confirmed that PEPs generally lead to an increase in property firm values during the announcement period in China (Liu 2008; Zhang 2017; Zhou 2016).

Another notable characteristic of PEPs is the issuance of shares at a discount. Hertzel and Smith (1993) found that PEPs in the U.S. market were typically issued at a discount of around 20%, a result echoed by Barclay et al. (2007). Xu et al. (2017) reported that the average PEP discount in the Australian market was approximately 7%, while the figure was around 12% in Japan (Kato and Schallheim 1993). Studies have also confirmed the presence of discounted pricing for PEPs in China (He and Zhu 2009; Song et al. 2019; Yu et al. 2013; Zhang and Guo 2009; Zhang and Li 2008).

The literature also highlights negative long-term performances following PEPs. Barclay et al. (2007) documented a post-event stock price decline of approximately 9.8% within six months. Wruck and Wu (2009) observed a CAR of −25.27% over three years. Similar negative long-term performances have been observed in East Asian markets (Baek et al. 2006; Kang et al. 1999; Kato and Schallheim 1993). However, evidence from the Chinese market is mixed. Geng et al. (2011) and Yu et al. (2016) identified a negative long-term performance, whereas Dong et al. (2020) reported positive long-term outcomes. Louisiana et al. (2007) found that private placement in real estate investment trusts (REITs) exhibited a positive long-term performance, which is consistent with the findings of Zhou (2016) on the Chinese real estate industry.

The existing literature explains PEP dynamics primarily through the lenses of agency theory, information asymmetry, and behavioral finance. Wruck (1989) suggested that PEPs enhance corporate governance by involving external investors, thereby increasing firms’ value. Barclay et al. (2007) proposed the managerial entrenchment hypothesis, positing that most investors participating in PEPs are passive, and that discounts serve as compensation for not opposing management’s actions. Zhang et al. (2021) explored the potential for controlling shareholders to expropriate minority shareholders’ interests through PEPs, linking the phenomenon to agency conflicts. The certification hypothesis, an extension of the information asymmetry hypothesis (Myers and Majluf 1984), posits that, as PEP investors are typically sophisticated and well-informed, their participation signals the company’s high quality or undervaluation, leading to positive market reactions (Hertzel and Smith 1993); the authors further argued that these discounts are a kind of compensation for investors, who spend resources to acquire accurate information about a company. Additionally, the over-optimism hypothesis suggests that short-term positive market reactions are driven by investors’ inflated expectations of future gains, which are later corrected as stock prices revert to their intrinsic values (Hertzel et al. 2002; Marciukaityte et al. 2005).

The real estate market is also significantly impacted by industry-specific regulatory laws. For instance, Chen and Lin (2013) found that various regulatory policies influence real estate prices by adjusting supply and demand relationships, based on their study of commercial real estate in Shenzhen, China. Li et al. (2014) observed that market volatility increases during periods of tightening. Ge et al. (2023) confirmed that stricter credit policies for real estate firms reduce investment in both the real estate and manufacturing sectors, contributing to cyclical fluctuations in the Chinese economy.

2.2. Hypotheses

Based on the existing literature, we anticipated that PEPs in Chinese real estate firms would exhibit significant positive announcement effects. The monitoring hypothesis suggests that external investors exert greater oversight, reducing agency costs and eliciting positive market reactions (Wruck 1989). These effects are likely to vary depending on the prevailing policy environment within the industry. From the perspective of the asymmetric information hypothesis, Myers and Majluf (1984) argued that managers of undervalued firms with limited financial flexibility may forgo issuing equity, even when faced with profitable investment opportunities, leading to an underinvestment problem. Hertzel and Smith (1993) proposed that, as PEPs involve fewer investors, they can more effectively signal a firm’s true value while minimizing information costs. This problem can be alleviated when financing constraints are eased during periods of policy relaxation. The overreaction hypothesis suggests that investors often overestimate challenges during pessimistic periods and overestimate opportunities during optimistic times (Hertzel et al. 2002). The market may overreact to perceived financing and sales difficulties in times of policy tightening, resulting in more unfavorable short-term market reactions. Conversely, during periods of policy relaxation, investors tend to be more optimistic, which leads to more favorable announcement effects.

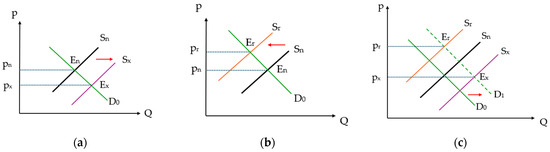

Figure 1 illustrates the equilibrium of capital supply and demand for real estate companies under different policy environments. In the diagram, and represent the supply and demand curves under a neutral policy environment, respectively, with indicating the equilibrium point. When the government announces a more favorable financing policy, the capital supply increases, leading to a new equilibrium point () in Figure 1a, where the cost of capital () decreases. Conversely, in Figure 1b, under tighter policy conditions, the cost of capital () rises.

Figure 1.

(a) The equilibrium of capital supply and demand during policy relaxation. (b) The equilibrium of capital supply and demand during policy tightening. (c) The equilibrium of capital supply and demand following PEP transactions across different policy periods.

Assuming that a real estate company conducts identical PEPs in both policy environments, the market is likely to anticipate a lower weighted average cost of capital during periods of policy relaxation, prompting an upward revision of the company’s valuation and, consequently, a more positive market reaction. In contrast, during periods of policy tightening, higher capital costs lead to a more negative market response. Even when accounting for the increased capital demands from real estate companies through PEPs, Figure 1c shows that the weighted average cost of capital () during policy relaxation remains consistently lower than the cost of capital () during policy tightening.

Therefore, we expect market reactions to be more positive during periods of relaxation compared to periods of tightening. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

In Chinese real estate companies, the announcement effects of PEP transactions are more positive during periods of policy relaxation than during periods of policy tightening.

Stricter financing regulations during policy-tightening periods make it more difficult for real estate enterprises to obtain capital through traditional financial channels, leading them to turn to alternate sources, such as PEPs. Higher discounts are expected as the demand for funds rises. Furthermore, regulations that increase down-payment requirements and place restrictions on real estate transactions for households further reduce sales revenue. Less available land and more stringent requirements for bidding on development projects exacerbate this situation during periods of tightening.

As discussed in Figure 1, there are significant differences in the costs of capital under different policy environments. Investors are likely to demand higher discounts during periods of policy tightening to compensate for the increased risks associated with higher capital costs and potential declines in company value. Consequently, it is reasonable to expect that PEP investors will require greater discounts during periods of policy tightening compared to periods of relaxation, as recompense for heightened risks and potential decreased profits. Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

In Chinese real estate companies, the discount rate for PEP transactions is lower during periods of policy relaxation than during periods of policy tightening.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Selection

This study focuses on Chinese A-share listed real estate companies that conducted PEPs between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2023. The data were sourced from the CSMAR database, excluding companies listed in Hong Kong due to the significant differences in private placement mechanisms. Unlike mainland China, equity placements by Hong-Kong-listed companies only require board approval, without additional regulatory oversight.2 This difference could influence the research results and interpretations. Thus, we excluded mainland real estate companies listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange from this study. We selected this timeframe because PEP transactions in China commenced in 2006, and the real estate industry did not experience significant fluctuations in its economic cycle during this period, providing an ideal context for analyzing the effects of policy environments on PEPs.

To ensure this study’s rigor and relevance, the sample was filtered using the following criteria: (1) Only companies classified within the real estate sector at the time of the PEP transaction were included.3 (2) Companies that engaged in other refinancing activities within a year before or after the transaction were excluded.4 (3) Companies lacking available financial or transaction data were excluded. (4) Cancelled transactions, unrecorded deals, or those still in progress were excluded. (5) Companies with PT or ST status at the time of the transaction were excluded.5 (6) In cases where companies conducted two PEP transactions on the same day, typically issuing shares for asset purchases and raising acquisition funds through new shares, the transactions were consolidated. This was conducted to account for different prices and share quantities, enabling accurate calculations of the discount rate for the PEP announcement effect study.6 After consolidating these same-day transactions, the final sample consisted of 126 events.

Additionally, to account for potential price discrepancies due to long trading suspensions, transactions with suspension periods exceeding seven days were excluded from the announcement effect analysis. This adjustment resulted in a final sample of 109 events for the announcement effect analysis.

The basic statistical descriptions of the sample companies are summarized in Table 1. Table 1a presents key data on the PEPs conducted by Chinese real estate companies. The average discount rate is 10.5%, with a median of 15.50%, which is consistent with findings from the existing literature. On average, the funds raised per transaction amounted to approximately 3.32 billion CNY, with the issuance size representing 26.70% of the total shares. The participating companies have an average total asset size of 30.70 billion CNY, with a median of 8.05 billion CNY, suggesting that primarily small-to-medium-sized real estate firms tend to engage in PEPs. The average ownership stake of major shareholders is 39.79%, with a median of 41.26%, consistent with the findings of Chen and Wang (2005). Such high levels of ownership suggest that the major shareholders in these real estate firms maintain substantial control over the companies and are less concerned about the dilution of control through PEPs. Additionally, the average debt ratio among the participating companies stands at 66.20%, reflecting the high leverage typical of the sector, as also noted in prior studies (Fang et al. 2016; Xiong 2023). Finally, the average return on equity (ROE) for these real estate firms is 9.30%, and Tobin’s Q ratio is 1.65, indicating a strong profitability and financial health during the study period.

Table 1.

(a) Descriptive statistics. (b) Statistics of PEPs across different policy periods.

Table 1b presents statistical data on PEPs across different policy environments. The data show a relatively balanced distribution of transactions between periods of policy tightening and relaxation, with 65 PEPs occurring during tightening periods and 61 during relaxation periods.

3.2. Announcement Effect Estimation

We employed the market model approach of De Jong et al. (1992) to estimate abnormal returns. The specific formula used is as follows:

where is the day relative to the event; is the return for company on date ; is the daily return of the Shanghai Real Estate Industry Index, used as a proxy for the market portfolio of risky assets; is the intercept of the equation; represents the OLS estimates of company ’s market model parameters; and is the error term of company on the sample event day .

The abnormal return () for company on date is calculated as follows:

The is the cumulative abnormal return (CAR) of company over the event window , starting from the lower bound of date , and is given as follows:

As described by Wruck (1989) and Hertzel and Smith (1993), we used the following formulae to calculate the adjusted CAR and AR:

where represents the adjusted CAR according to the method of Wruck (1989) and Hertzel and Smith (1993); represents the adjusted AR according to the method of Wruck (1989) and Hertzel and Smith (1993); is the ratio of shares placed to the total outstanding after the event; represents the close price one day before the event; and is the price of PEPs.

3.3. Discount Calculation

The discount rate was calculated based on the method outlined by Wruck and Wu (2009), as follows:

where is the benchmark price according to Wruck and Wu (2009) and is the price of the private equity placement transaction.

3.4. Regressions and Variable Definitions

We developed a regression model to investigate the impact of the industrial policy environment on the announcement effect, as shown in Equation (7), as follows:

Similarly, we structured the following regression model in Equation (8) for the discount study:

In Equations (7) and (8), the selected dependent variables are the short-term cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) of PEPs and the discount rate (Discount), respectively. The key research variable is Policy, which takes a value of 1 during periods of policy tightening. The control variables (denoted as Control Variables) are those selected to account for other influencing factors, with detailed definitions provided in Table 2. Fixed Effect represents the year or regional indicator variables used to capture time- or region-specific variations. Finally, represents the error term in the regression model.

Table 2.

Variable definitions.

Previous research presents divergent views on the relationship between discount rates and announcement effects in PEPs. Some studies suggest that lower discount rates reflect reduced agency costs and improved information asymmetry (Marciukaityte et al. 2005; Zhang and Li 2008), while others find a positive correlation between discount rates and short-term stock price movements. This implies that firms may offer greater discounts to attract market attention (Chaplinsky and Haushalter 2005; Lu et al. 2011). According to the information asymmetry hypothesis, controlling shareholders possess an information advantage over external investors. Consequently, investors may interpret the participation of controlling shareholders as a signal of undervaluation or high project profitability, leading to lower discount demands (Zhang and Li 2008). On the other hand, Wang et al. (2020) argued that controlling shareholders can manipulate issuance prices through fixed pricing methods, but auction-based pricing in PEPs mitigates the risk of such tunneling behavior.

Gu and Wu (2014) noted that larger fundraising efforts not only demonstrate shareholder confidence, but may also involve significant capital events, such as asset acquisitions, which can influence market expectations regarding profitability. Larger fundraising efforts are likely to attract greater market attention, triggering stronger market reactions. In our model, we also used the natural logarithm of the number of shares issued (Ln_share) as an alternative proxy for Proceed to conduct robustness tests. Hertzel and Smith (1993) argued that a larger fraction placed indicates the greater importance of investment opportunities, necessitating more resources for investors to evaluate the true value of the firm, often leading to a greater discount. Similarly, we employed Rsize as a substitute for Fraction for robustness tests. According to Wruck (1989), PEPs can alter the ownership concentration, potentially leading to changes in voting rights or deterring hostile takeovers, thereby generating positive announcement effects.

Profitability metrics such as ROE, ROA, and Tobin’s Q are key indicators of a firm’s financial health and market expectations. Higher values for these variables indicate a better firm quality and lower risk, which should result in more favorable market reactions and lower discount rates. Hertzel and Smith (1993) observed that smaller firms tend to face more severe information asymmetry, prompting investors to demand greater discounts to compensate for this risk. In contrast, larger firms typically benefit from better financing options and a higher overall quality, resulting in smaller discounts. The variation in announcement effects across firms of different sizes depends on how the market interprets the deal. Larger, less risky firms tend to receive more positive reactions, while smaller firms may see a stronger stock price response if the market anticipates that the PEP will substantially enhance their performance. Since PEPs generally reduce a firm’s leverage, prior studies have found a positive relationship between leverage and announcement effects (Sun 2015). Moreover, changes in leverage signal a reduced risk of bankruptcy, which can lead to stronger announcement effects and smaller discount rates.

Lin and Rao (2009) argued that investor irrationality can amplify extreme market reactions. During bull markets, investors may demand higher discounts to compensate for excessively optimistic sentiments. Board size (Board) is commonly used to assess agency problems within a company. Jensen (1993) argued that smaller boards are more conducive to monitoring, while larger boards can exacerbate agency issues. Similarly, the proportion of independent directors (Indboard) and the variable Balance are used to evaluate the effectiveness of internal governance mechanisms and power balances. Finally, management fees (Mfee), often considered to be a proxy for hidden management benefits (Lu et al. 2008), indicate the severity of agency problems, with higher fees reflecting more significant agency problems. As a result, when agency problems are more severe and internal controls are weaker, investors tend to demand greater discounts to compensate for the increased risk.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Policy Environment History and PEP Transactions in China

Table 3 outlines the evolution of policies in China’s real estate sector since the beginning of its economic reforms. The sector’s marketization began in 1980, when the State Council approved the “Summary of the National Urban Planning Work Conference”. In 1981, the first real estate development company, the China Real Estate Development Group Corporation, was established. By 1987, the land market had emerged, marked by the first public auction of land use rights in Shenzhen. In 1991, China Vanke became the first publicly listed real estate company. Following Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour in 1992, economic growth accelerated, but unregulated investments triggered the Hainan Island real estate bubble. This prompted the government to introduce the “16 Measures for National Economic Stabilization” in 1993, initiating the era of real estate regulation.

Table 3.

Policy trends of China’s real estate industry (source: Huaxi-Security (2023)).

During the 2008 global financial crisis, the government introduced a Four-Trillion Yuan infrastructure investment plan, easing restrictions and implementing supportive policies in the real estate sector to steer the economy back onto the path of growth. Before 2016, the government implemented a series of relaxed policies aimed at reducing real estate inventory, which led to a significant rise in property prices in most Chinese cities (Fang et al. 2016; Rogoff and Yang 2021; Xiong 2023). To curb speculative activities, the government introduced the “housing is for living, not for speculation” principle in 2016, along with the “Three Red Lines” policy to limit real estate companies’ debt. In response to the economic slowdown and the weakening of the real estate market following the COVID-19 pandemic, the government once again adopted a more relaxed policy stance, aiming to support struggling real estate companies and stabilize the sector’s growth trajectory.

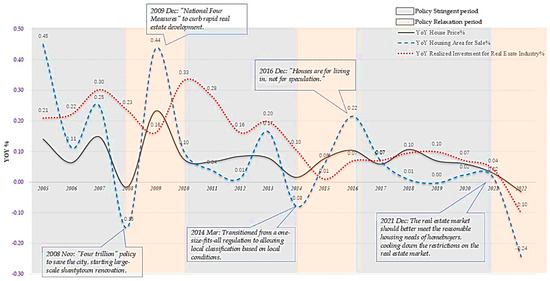

Frequent policy adjustments are illustrated in Figure 2. The solid black line represents the year-on-year change in housing prices, while the dashed dark green line depicts the year-on-year change in real estate sales area and the dashed red dotted line reflects the year-on-year change in real estate investment. The light blue shaded regions indicate periods of policy tightening, whereas the pink shaded areas represent phases of policy relaxation. The data reveal that, since 2005, the number of policy-tightening periods has slightly exceeded that of policy-loosening phases. During periods of policy tightening, there are significant declines in the growth rates of housing sales area, prices, and investment. In contrast, periods of policy relaxation demonstrate significant rebounds in these indicators. This highlights the substantial impact that the policy environment has on the real estate market.

Figure 2.

Policy environment for China’s real estate industry (source: China National Bureau of Statistics, Huaxi-Security (2023), authors).

PEPs in China were introduced in 2006 following the CSRC’s issuance of the “Administrative Measures for the Issuance of Securities by Listed Companies”, which detailed regulations on non-public offerings.7 Compared to other forms of SEO, PEPs offer more flexible issuance requirements. For instance, while public offerings and convertible bonds require a minimum 6% return on equity over the previous three years, PEPs have no such requirement (Xu 2011). PEPs also offer several other advantages, such as lower issuance costs (Xu 2011), more flexible pricing mechanisms (Tao et al. 2018), and a lock-up period that mitigates the immediate impact on stock prices (Yi et al. 2006; Zhang and Guo 2009). Due to these advantages, PEPs have become one of the most important refinancing tools for Chinese listed companies since their inception. Shi et al. (2020) highlighted that the funds raised through PEPs in 2017 had increased nearly tenfold since 2006.

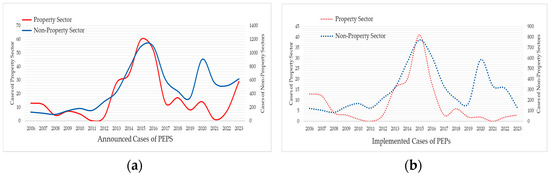

Figure 3 compares the annual issuance frequencies of PEPs between the real estate and non-real estate sectors. Panels (a) and (b) illustrate the number of companies announcing and completing PEP transactions, respectively. This comparison reveals two distinct peaks in PEP announcements and completions for non-real-estate sectors, while the real estate sector experiences only one peak. As depicted in Figure 3, the peak for real estate PEPs occurred around 2015, coinciding with a period of policy relaxation. In contrast, the second peak in non-real-estate PEPs around 2020 occurred during a period of policy tightening, at a time when the real estate sector experienced fewer announcements and successful transactions. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a noticeable rise in PEP announcements in the real estate sector, aligning with a phase of policy relaxation.8 For instance, in August 2023, while the CSRC suspended private placement approvals, real estate enterprises were exempted from these restrictions (Ning and Jalil 2023). This highlights the significant impact of industry policy environments on refinancing activities in the real estate sector.

Figure 3.

(a) The announced cases of PEP transactions during 2006–2023. (b) The implemented cases of PEP transactions during 2006–2023. Data source: China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database.

4.2. Announcement Effects in Various Policy Environments

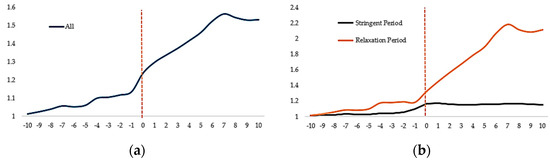

Table 4 compares the announcement effects across different periods using CARs and adjusted CARs, as calculated by Equations (3) and (4), respectively. Consistent with the previous literature, the results indicate a significant positive announcement effect for PEPs in Chinese real estate companies. For example, Table 4a reveals that, within the [−10, +10] event window, the average CAR is 13.35%, which is statistically significant at the 1% confidence level. This positive effect persists across various time windows and adjusted CAR tests. Figure 4a further illustrates these findings.

Table 4.

Comparison of announcement effects across policy periods: (a) comparison of CARs and (b) comparison of adjusted CARs.

Figure 4.

(a) The adjusted CAR of all samples in the [−10, 10] event window. (b) The comparison of the adjusted CAR across the industrial policy environments in the [−10, 10] event window. The left side of the vertical dashed line represents the period before the event, while the right side represents the period after the event. Source: authors.

Moreover, Table 4 demonstrates that PEPs continue to have a significant positive impact on the value of real estate firms even during periods of policy tightening. This suggests that the market perceives PEPs as a mechanism that can enhance oversight, thereby reducing agency problems or addressing information asymmetry (Hertzel and Smith 1993; Wruck 1989). Additionally, the announcement effect is notably more pronounced during periods of policy relaxation compared to those of policy tightening. For instance, in the [−5, +5] window, Table 4a reports a CAR of 6.55% during policy tightening and 14.64% during policy relaxation, with both figures being statistically significant. The 8.09% difference between the two periods was confirmed by subsequent T-tests and Wilcoxon tests, as well as being visualized in Figure 4b. However, when adjusted CAR is used, the difference between tightening and relaxation periods remains positive, but is not statistically significant.

Table 5 extends the analysis by comparing the average abnormal returns (AARs) during the [−10, +10] event window under varying policy environments. The results show that these AARs are generally higher during policy relaxation periods compared to policy-tightening periods—a trend that is also reflected in Figure 4b. This suggests that, during policy relaxation, the market is more optimistic about the potential profitability and prospects of real estate firms conducting PEPs. While PEPs still generate positive market reactions during policy-tightening periods, the response is more muted.

Table 5.

The adjusted AARs in the event window [−10, 10] for different policy environments.

4.3. The Multiple Regression Analysis on CAR in Announcement Periods

In the model of Hertzel and Smith (1993), the CAR of the event window [−5, 0] is used as the dependent variable. However, we observed that the average AR in our sample continued to exhibit significant changes even after the announcement date, as shown in Figure 4 and Table 5. Therefore, it is more appropriate to extend the event window to include post-announcement data. At the same time, selecting a longer time window increases the likelihood of interference from other market events. Considering these factors, we chose the CAR within the [−3, +3] window as the dependent variable for our models, while using the CAR of the [−5, +5] window as the dependent variable for robustness testing. We conducted a regression analysis using a fixed-effects model and performed robustness tests by substituting control variables.

Table 6 presents the regression results for the announcement effects of PEPs. The results show that the relationship between Policy and CAR is opposite in Panels (a) and (b), but neither result is statistically significant. This suggests that the policy environment does not have a significant impact on the announcement effects of PEPs.

Table 6.

Regression results of PEPs’ announcement effects: (a) regression results for event windows [−3, 3] and [−5, 5] and (b) regression results for robustness tests.

The results also reveal a significant positive relationship between fundraising amounts (Proceed) and announcement effects, aligning with the findings of Gu and Wu (2014). This may be because larger fundraising efforts in the real estate sector attract greater market attention, or because PEPs may involve asset acquisitions that significantly enhance a firm’s operational capabilities. Interestingly, in contrast to the findings of other scholars (Lu and Chen 2015; Sun 2015), our regression results reveal a positive relationship between Leverage and CAR, which is significant in all models except Model (3). Furthermore, changes in leverage (Chg_Lev) are also significantly positively correlated with announcement effects. These findings suggest that the market tends to view more aggressive investment behavior by real estate firms favorably. Further analysis in Table 7 indicates that, before 2014, the market responded more positively to leverage-increasing activities by real estate firms. However, after 2014, the market reaction to such aggressive investment strategies became more mixed or conservative, which is consistent with the broader development trends in China’s real estate sector.

Table 7.

Further analysis of the impact of leverage and changes in leverage on announcement effects.

The results show that announcement effects are weaker during bull markets. According to the over-optimism hypothesis, the market discounts investors’ overly optimistic expectations of firms, leading to a more muted market reactions (Marciukaityte et al. 2005). Moreover, we found that higher management fees (Mfee) in Chinese real estate firms were associated with stronger announcement effects. While excessive managerial perks are generally seen as being detrimental to firms’ performance (Edgerton 2012; Lu et al. 2008; Yermack 2006), some studies suggest that management fees should not be viewed solely as transaction costs. Research has shown that increases in both total and per capita management expenses can significantly enhance total factor productivity in Chinese firms (Yao et al. 2022). Our findings suggest that the market interprets higher management fees as an indication of proactive management engagement, which elicits a positive response.

We then conducted a group regression analysis of announcement effects under different policy environments, as shown in Table 8. The VIF values for all variables across the models were below 2.5, with the average VIF being less than 2, indicating no multicollinearity issues. The results reveal a significant positive relationship between changes in leverage and announcement effects during both tightening and relaxation periods. This supports the full sample findings, as follows: the market tends to favor aggressive investment behavior by real estate firms, particularly in unfavorable policy environments, where such strategies are perceived more positively. Consistent with the overall results, the market discounts overly optimistic sentiments during tightening periods.9

Table 8.

Regression results of announcement effects under different policy environments.

Similar to the findings of Chaplinsky and Haushalter (2005) and Lu et al. (2011), we observed that the discount rate has a significant positive effect on short-term stock prices during relaxation periods. This suggests that real estate firms may attract market attention through larger discounts or signal undervaluation to the market (Hertzel and Smith 1993). Interestingly, during policy-loosening periods, the market responds negatively to variables related to firm quality and prospects. For example, both Tobinq and ROE exhibit a negative correlation with CAR, suggesting that the market may question the marginal benefits of PEPs for firm growth and quality during these times. On the other hand, the positive impact of the independent director ratio on short-term performance highlights that corporate governance becomes a more prominent concern for the market during relaxation periods. This indicates that, while the market focuses on transaction- and company-specific characteristics during loosening phases, investor sentiment takes precedence during periods of tightening.

To further investigate, we conducted a comparative analysis of the industry policy environment, as outlined in Table 9. We applied various grouping standards and utilized a permutation test, which performed 500 bootstrap resamples to derive empirical p-values for evaluating the significance of the industry policy environment variable coefficients. For brevity, we present only the analysis results for groupings based on ROE and discount rates in this section.

Table 9.

Heterogeneity analysis of PEP announcement effects.

In Models (1) and (2), the sample is divided into high- and low-ROE groups. The results indicate that, although the policy environment shows a negative correlation with announcement effects in both groups, this relationship is not statistically significant. The empirical p-value is 0.128, suggesting that the property firm’s ROE does not significantly alter the impact of policy environment factors on announcement effects. In the high-ROE group, short-term stock price movements around the event are influenced by factors such as the discount rate, Tobin’s Q, leverage and its changes, and corporate governance quality. Conversely, in the low-ROE group, announcement effects are driven by ownership concentration, market sentiment, and management fees, in addition to the discount rate.

Models (3) and (4) classify the sample based on discount rate levels. The analysis reveals that, although the coefficients for the policy environment variable are negative in both groups, they are not statistically significant. However, the empirical p-value of 0.09 suggests that the impact of the policy environment on announcement effects does vary significantly across different discount rate levels. Furthermore, in the high-discount-rate group, announcement effects are significantly influenced by changes in leverage, market sentiment, and management fees. Meanwhile, in the low-discount-rate group, the key drivers are fundraising, Tobin’s Q, and leverage and its changes.

Overall, while differences in the policy environment lead to significant variations in announcement effects under different discount rates, there is no substantial impact of the policy environment on short-term stock price changes in either the ROE or discount rate groups. This finding is consistent with our conclusion from the full sample analysis.

4.4. Discount Comparisons across Different Policy Environments

Table 10 compares discount rates across different industry policy environments. As shown in Table 10a, during periods of policy relaxation, the discount rate for PEPs reached 16.76%, with an alternative calculation method yielding a discount rate of 25.32%. In contrast, during periods of policy tightening, real estate firms did not offer discounts on newly issued shares, resulting in a premium rate of 5.83%. Even after applying trimming techniques, as illustrated in Table 10b, the results remained consistent. Both T-tests and Wilcoxon tests confirmed that the difference in discount rates between different policy periods was statistically significant. This finding is inconsistent with Hypothesis H2.

Table 10.

Discount comparisons: (a) discount comparison without trimming and (b) discount comparison with trimming at the 5% and 95% percentiles.

4.5. The Multiple Regression Analysis on Discount

Table 11 presents the regression results on discount, utilizing alternative control variables to test the robustness of the findings. The findings reveal a significant negative relationship between the industry policy environment variable (Policy) and the discount rate, indicating that discount rates tend to be lower during stringent periods and higher during relaxation periods. This relationship remained consistent across various robustness checks, confirming the findings in Table 10 and suggesting that the policy environment plays a crucial role in pricing negotiations.

Table 11.

Regression results for discount: (a) regression results for different discounts and (b) regression results for robustness tests.

During periods of tightened policy, real estate companies often struggle to secure traditional bank financing, prompting them to turn to the securities market for PEPs to raise funds or supplement liquidity. Since PEPs in China require approval from the CSRC (Song 2014), companies that complete PEPs effectively receive quality certification from the authorities. As a result, during periods of tightened policy, only high-quality companies can execute PEPs, mitigating the adverse impact of the policy. Additionally, the long-term growth of China’s real estate sector has strengthened investors’ confidence in high-quality firms’ ability to improve their performance during challenging policy periods, leading investors to accept lower discount rates in exchange for promising investment opportunities.

The results in Table 11 also demonstrate that, when major shareholders participate in PEPs, the discount rate is lower. This significant finding contradicts Zhang et al. (2021), who argued that major shareholders manipulate discounts for tunneling purposes; instead, it supports the certification hypothesis, as investors perceive the participation of major shareholders as a positive signal that the company is undervalued. The regression results also confirm that, when the auction pricing model is employed, the discount rate is lower. This is consistent with the argument by Wang et al. (2020) that fixed pricing models are more prone to manipulation by major shareholders, whereas auction models reduce the likelihood of tunneling behavior, thereby leading to lower discount rates.

Table 12 extends the analysis of discount rates across different policy environments. The results indicate that, during periods of tightened policy, the participation of controlling shareholders significantly reduces the discount rate, while no such effect is observed during periods of policy relaxation. This suggests that, in unfavorable policy environments, investors place a greater emphasis on the accuracy of the signals conveyed (Zhang and Li 2008). Controlling shareholders’ participation provides external investors with a clear anchor. Consistent with the findings of Hertzel and Smith (1993), the amount raised is negatively correlated with the discount rate; they argued that the existence of economies of scale leads to a decrease in the unit cost of information production as the amount raised increases. Additionally, the positive correlation between the fraction placed and the discount rate aligns with the conclusion of Hertzel and Smith (1993) that investment opportunities are more difficult to value than existing assets. A larger fraction placed suggests a more significant investment opportunity, which requires investors to commit more resources.

Table 12.

Regression results of discount under different policy environments.

During periods of policy relaxation, the proceeds and the fraction placed are not primary factors for investors in negotiations. This difference likely stems from the fact that, during periods of tightened policy, investors are more concerned with the cost of projects and their likelihood of success. Moreover, the information asymmetry hypothesis suggests that smaller companies typically face higher levels of information asymmetry, which should result in greater discounts (Hertzel and Smith 1993); however, our findings contradict this view. Zhang et al. (2021) offered an alternative explanation, suggesting that larger companies are more likely to engage in tunneling behavior by controlling shareholders, prompting investors to demand higher discounts to compensate for this risk. Table 12 indicates that this phenomenon occurs primarily during periods of tightened policy, reflecting investors’ more cautious approach to PEPs in such environments. On the one hand, investors acknowledge the positive signals from controlling shareholders’ participation, while, on the other hand, they remain wary of potential tunneling behavior.

The results also reveal that, during periods of policy tightening, ROE is positively correlated with the discount rate. This suggests that investors bet on the possibility that PEP-related projects could turn around the company performance during difficult times, rather than relying on the company’s inherent profitability. Finally, ownership balance only significantly affects the discount rate during periods of relaxed policy. Although a higher ownership balance implies greater constraints on controlling shareholders, investors may be concerned that a reduction in the controlling shareholders’ influence could lead to missed investment opportunities due to inefficient decision making in favorable market conditions; as a result, they may demand a higher discount to compensate for this uncertainty.

Table 13 presents a comparative analysis of the variable Policy based on the two following criteria: major shareholder participation in PEP transactions and the pricing model used. Models (1) and (2) indicate that, when major shareholders participate in the PEP transaction, the discount rate significantly decreases during periods of tightened industry policy. This supports the certification role of major shareholders, particularly in adverse policy environments, where both the CSRC and the major shareholders provide a dual certification of the company’s quality. This finding is consistent with the certification hypothesis (Hertzel and Smith 1993). However, the empirical p-value for this group is 0.208, suggesting that the difference in the policy environment’s impact is not statistically significant between the samples with or without major shareholder participation. In Models (3) and (4), a significant negative correlation is observed between the policy environment and the discount rate, regardless of whether the pricing model is an auction or a fixed-price mechanism. However, the empirical p-value is 0.366, suggesting that the impact of the industry policy environment on the discount rate does not differ significantly between the two pricing models. This suggests that investors treat the policy environment as an independent factor during negotiations, regardless of shareholder participation or pricing mechanisms.

Table 13.

Analysis of discount rate heterogeneity in PEP transactions.

Evaluating the long-term performance of PEPs is challenging due to the fluctuations in policy environments over time, which could affect the reliability of such studies. Thus, this paper does not delve deeply into the effect on the long-term performance of PEPs. Nevertheless, long-term buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHARs) are calculated to further explore investors’ motivations for participating in these transactions.10 Previous research shows that companies with CSRC-approved PEPs tend to demonstrate a better long-term performance and ROE, especially when major shareholders are involved (Dong et al. 2020).

Table 14 displays the long-term BHARs for 250, 500, and 750 trading days post-transaction. To minimize the influence of the announcement period, the upper limit of the time window was set at 50 days after the event. The lower limits were set at one, two, and three years post-event, given that the average number of annual trading days in China is approximately 250. The results indicate a positive long-term performance for PEPs in Chinese real estate companies—a finding that contrasts with the results of several studies (Hertzel et al. 2002; Krishnamurthy et al. 2005; Wruck and Wu 2009; Yu et al. 2016), but is consistent with the results of Louisiana et al. (2007) and Zhou (2016). In the Chinese market, this typically takes around a year to implement, and newly subscribed shares usually have a one-year lock-up period. Under these conditions, investors are willing to accept smaller discounts in exchange for valuable investment opportunities, resulting in a significant abnormal return of 15.42% after two years. This finding challenges overly optimistic assumptions and explains why investors may accept lower discounts or even pay premiums to secure valuable opportunities, even in unfavorable policy environments.

Table 14.

The BHARs for long-term performance.

5. Conclusions

This study examined private equity placement transactions in Chinese real estate companies from 2006 to 2023, revealing several key insights. While confirming the positive announcement effects reported in the existing literature, our findings reveal that market reactions are less pronounced during periods of stringent industry policies when compared to more relaxed policy environments. The positive announcement effects observed across the full sample suggest that the market interprets PEPs as an indication of increased regulatory oversight, reduced agency costs, lower capital costs, or alleviated information asymmetry in real estate companies. However, the regression results indicate that the policy environment is not a decisive factor in determining PEPs’ announcement effects in the Chinese real estate sector.

Instead, other variables emerged as significant drivers of announcement effects. During bull markets, market sentiment has a significant negative impact, indicating that investor irrationality leads to discounted valuations for PEP transactions. Additionally, announcement effects are significantly positively related to the amount raised, changes in leverage, and management fees. Notably, the market responded favorably to increases in leverage before 2014, but became more conservative post-2014. This shift reflects broader trends in the real estate sector and changes in investor behavior. Interestingly, higher management fees are interpreted by the market as a sign of proactive business activities, encouraging firms to seize development opportunities, especially during boom phases in the sector.

Our analysis also showed that, during periods of policy relaxation, the market focuses on transaction and company characteristics, while investor sentiment becomes a key focus during tightening periods. Heterogeneity analysis further revealed that, although the policy environment affects announcement effects differently across various discount rate levels, it does not significantly impact these effects across different discount rate or ROE groupings, consistent with our previous findings.

We also found that the industry policy environment plays a significant role in investors’ bargaining power. Contrary to our expectations, discounts on PEPs are smaller during policy-tightening periods. This can be attributed to the fact that successful PEPs require approval from the CSRC, which acts as a quality certification, especially when major shareholders are involved. Additionally, long-term performance data show positive returns for PEPs in the Chinese real estate sector, suggesting that investors are willing to accept smaller discounts in exchange for potentially substantial future gains. This supports the certification hypothesis (Hertzel and Smith 1993) while contradicting overly optimistic hypotheses (Hertzel et al. 2002; Marciukaityte et al. 2005).

Our findings reveal that major shareholder participation and auction pricing models significantly reduce discount rates, highlighting the importance of shareholder endorsement and the mitigation of tunneling risks. During periods of policy tightening, investors tend to interpret major shareholders’ involvement as a signal of potential undervaluation, while remaining cautious about the possibility of tunneling. The relationship between proceeds, fractions placed, and discounts during tightening periods supports the certification (information production) hypothesis. Notably, in unfavorable policy environments, investors focus more on the potential of PEPs to improve company performance, while, under favorable policy conditions, they express concerns about missed opportunities due to inefficiencies in decision making. Finally, a heterogeneity analysis of discount rates showed that investors treat industry policy as an independent factor in PEP negotiations. Overall, the evidence strongly supports the certification hypothesis, while also indicating that PEP dynamics are influenced by the evolving characteristics of the industry and its various stages of development.

This study offers several implications for real estate companies, investors, and policymakers. Real estate firms should pay close attention to the substantial impact of the industry policy environment on PEP bargaining and understand how different policy preferences challenge their operational capabilities. Companies can benefit from leveraging the certification provided by major shareholders to attract investor participation, strengthen corporate governance, and adopt auction pricing models to reduce the risks of tunneling behavior. For investors, it is essential to recognize the distinct characteristics of real estate PEPs, acknowledging that, despite smaller discounts, both short-term and long-term returns can be positive. Accepting lower discounts in exchange for potentially substantial future returns is particularly reasonable in environments with constrained access to traditional financing. Policymakers, on the other hand, should be aware of the effects that industry policy environments exert on PEPs and should consider adjusting regulations to accommodate these dynamics. Additionally, implementing institutional frameworks to guide the behavior of major shareholders and encourage long-term investment strategies would help to foster a more stable and sustainable market.

Given the scope of this study, we cannot delve into every detail extensively. Our research focused primarily on the rapid development phase of China’s real estate sector, but the post-COVID-19 economic slowdown, which has caused widespread losses in the industry, may influence PEPs and their underlying mechanisms.11 It is important to acknowledge that the relatively small sample size in this study may affect the stability of the conclusions. As the sample size increases, the findings could evolve. Future studies could address this limitation by expanding the dataset to improve the robustness and generalizability of the results. Additionally, we did not analyze failed PEPs, and examining the differences between these and successful transactions could offer valuable insights. This study does not delve deeply into specific cases, limiting the practical understanding of how these transactions operate. Furthermore, the significant differences in PEP regulations between the Hong Kong and mainland Chinese markets, along with the exclusion of private firms from this study, highlight potential avenues for future research. Overall, the Chinese real estate sector offers a valuable experimental platform for studying the impacts of industry-specific factors and varying policy environments on PEP transactions, deepening our understanding of corporate management practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.N. and R.B.A.J.; methodology, Y.N. and R.B.A.J.; validation, Y.N.; formal analysis, Y.N. and R.B.A.J.; data curation, Y.N.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.N.; writing—review and editing, Y.N. and R.B.A.J.; supervision, R.B.A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express special gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and guidance on the early versions of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

In certain cases, a company may initiate two placements on the same day, with one issuance of shares aimed at acquiring other assets and the other for raising matching funds. These transactions often have different issuance prices and quantities of shares, complicating the calculation of the discount rate. To address this issue, the following method is proposed for calculating the discount rate under these special circumstances:

where represents the combined discount rate for the two placements occurring on the same day; is the benchmark closing price, determined using the method outlined by Wruck and Wu (2009), which considers the closing price on the last day before the event or the closing price on the tenth trading day after the event; and are the number of shares issued in the first and second placements on the same day, respectively; and and are the issuance prices of the first and second placements, respectively.

Appendix B

According to Hertzel et al. (2002), the formula for calculating BHAR is as follows:

where represents the buy-and-hold abnormal return for company during period , represents the buy-and-hold return for company during period , and represents the buy-and-hold return for the benchmark during period .

Notes

| 1 | For a detailed analysis of China’s hybrid economic development model based on the real estate sector, see Xiong (2023). |

| 2 | For details regarding equity placement regulations in the Hong Kong market, please refer to the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited, as well as other relevant provisions. |

| 3 | There are instances where companies are included in or excluded from the real estate sector due to changes in their primary business operations. This study primarily focuses on whether companies belonged to the real estate industry during the period of the PEP transaction. |

| 4 | Other financial activities include public offerings, rights issues, convertible debt, etc. |

| 5 | When a listed company encounters financial difficulties or other operational issues, the exchange typically labels its stock as “PT” (Particular Transfer) or “ST” (Special Treatment). Investors should exercise caution with these stocks due to their higher risk and the possibility of delisting. |

| 6 | The method for calculating the discount rate after consolidation is detailed in Appendix A. |

| 7 | For further details on the regulation and issuance mechanisms of PEP transactions, see Ning and Jalil (2023) and Song (2014). |

| 8 | During this period, the lower number of successfully completed transactions was due to several PEPs still being in the process of implementation. |

| 9 | In the models for the policy loosening period, the market sentiment variable Bull exhibited significant multicollinearity with the models. Consequently, this variable was excluded from Models (3) and (4). |

| 10 | The formula for BHAR is shown in Appendix B. |

| 11 | Aside from the unexpected bankruptcy of China Evergrande, other major industry players, such as Country Garden, have also faced significant debt crises. Notably, China Vanke, the first publicly listed real estate company in China, reported its first loss since its initial public offering in 2024. This reflects the challenging operating conditions faced by the entire industry at this stage. |

References

- An, Hui, and Ruidong Wang. 2013. An Empirical Analysis of Influencing Factors in Real Estate Prices of China and The Current Real Estate Regulating Policy. Finance & Economics 3: 115–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Jae-Seung, Jun-Koo Kang, and Inmoo Lee. 2006. Business Groups and Tunneling: Evidence from Private Securities Offerings by Korean Chaebols. The Journal of Finance 61: 2415–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, Michael J., Clifford G. Holderness, and Dennis P. Sheehan. 2007. Private Placements and Managerial Entrenchment. Journal of Corporate Finance 13: 461–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnenkamp, Guido, and Christian Kammann. 2024. Current Developments on the Chinese Real Estate Market. International Journal of Innovation Economic Development 9: 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, David J., Paige Ouimet, and Clemens Sialm. 2004. PIPE Dreams? The Performance of Companies Issuing Equity Privately. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplinsky, Susan, and David Haushalter. 2005. Financing Under Extreme Uncertainty: Evidence from Private Investments in Public Equities. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=690186 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Chen, Xiao, and Kun Wang. 2005. Related Party Transactions, Corporate Governance and State Ownership Reform. Economic Research Journal 4: 77–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yan, and Guangzhen Lin. 2013. Research on the Policy Control of Commercial Real Estate in Shenzhen. Construction Economy 7: 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronqvist, Henrik, and Mattias Nilsson. 2004. The choice between rights offerings and private equity placements. Journal of Financial Economics 78: 375–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, Frank, Angelien Kemna, and Teun Kloek. 1992. A contribution to event study methodology with an application to the Dutch stock market. Journal of Banking Finance & Trade Economics 16: 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Gang Nathan, Ming Gu, and Hua He. 2020. Invisible Hand and Helping Hand: Private Placement of Public Equity in China. Journal of Corporate Finance 61: 101400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgerton, Jesse. 2012. Agency Problems in Public Firms: Evidence from Corporate Jets in Leveraged Buyouts. The Journal of Finance 67: 2187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Hanming, Quanlin Gu, Wei Xiong, and Li-An Zhou. 2016. Demystifying the Chinese housing boom. NBER Macroeconomics Annual 30: 105–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folta, Timothy B., and Jay J. Janney. 2004. Strategic benefits to firms issuing private equity placements. Strategic Management Journal 25: 223–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Lulan, Zhiyuan Li, Yongming Liu, and Ling Feng. 2023. Real Estate Credit Policies, Investment, and Macroeconomic Fluctuations in China. Nankai Economic Studies 2: 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Jianxin, Yuejin Lv, and Xiaoping Zou. 2011. An Empirical Study on the Long-Term Return Performance of Private Placements of Listed Companies in China. Journal of Audit & Economics 26: 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Haifeng, and Di Wu. 2014. Research on the influencing factors of the announcement effect of Private placement of Chinese listed companies: An empirical analysis based on event study method. Review of Economy and Management 30: 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Xianjie, and Hongjun Zhu. 2009. Tunneling, Information Asymmetry and Private Placement Discount. China Accounting Review 7: 283–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzel, Michael, and Richard L. Smith. 1993. Market Discounts and Shareholder Gains for Placing Equity Privately. The Journal of Finance 48: 459–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzel, Michael, Michael Lemmon, James S. Linck, and Lynn Rees. 2002. Long-run Performance Following Private Placements of Equity. The Journal of Finance 57: 2595–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Lipeng, and Yun Zhang. 2016. Announcement Effects of the Seasoned Equity Offerings and Private Placements of A-share Listed Companies. Finance Forum 21: 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaxi-Security. 2023. Historical Review of Real Estate Policies. Available online: https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H301_AP202305101586440193_1.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Jensen, Michael C. 1993. The Modern Industrial Revolution, Exit, And the Failure of Internal Control Systems. The Journal of Finance 48: 831–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Jun-Koo, Yong-Cheol Kim, and René M. Stulz. 1999. The Underreaction Hypothesis and The New Issue Puzzle: Evidence from Japan. The Review of Financial Studies 12: 519–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Kiyoshi, and James S. Schallheim. 1993. Private Equity Financings in Japan and Corporate Grouping (Keiretsu). Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 1: 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, Srinivasan, Paul Spindt, Venkat Subramaniam, and Tracie Woidtke. 2005. Does Investor Identity Matter in Equity Issues? Evidence From Private Placements. Journal of Financial Intermediation 14: 210–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Minghui. 2009. The influence of ownership structure and corporate governance on equity agency cost: A study based on the data of Chinese listed companies from 2001 to 2006. Journal of Financial Research 2: 149–68. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xiangfei, Zaisheng Zhang, and Chao Huang. 2014. Study of Influence Estate Control Policies on Real Estate Index Based on the Method of Hilbert-Huang Transform. Systems Engineering-Theory & Practice 34: 1369–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Bin, and Jing Rao. 2009. Why do Listed Companies Disclose the Auditor’s Internal Control Reports voluntarily?—An Empirical Study Based on Signaling Theory in China. Accounting Research 2: 45–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Frank, and Gerard Gannon. 2007. Private Placement and Share Price Reaction: Evidence from The Australian Biotechnology and Health Care Sector. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=9b295d40433342e96b4c31df137a6c28e1d4df40 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Liu, Lixue. 2008. An empirical study on stock price effect of Private placement announcements of Chinese listed companies. Pioneering with Science & Technology Monthly 10: 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louisiana, Dalia, Eric Higgins, H. Friday, and Joseph Mason. 2007. Positive Performance and Private Equity Placements: Outside Monitoring or Inside Expertise? Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management 13: 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Deng, Sifei Li, and Weixing Wu. 2011. Market Discounts and Announcement Effects of Private Placements: Evidence from China. Applied Economics Letters 18: 1411–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Rui, Minghai Wei, and Wenjing Li. 2008. Managerial Power, Perquisite Consumption and Performance of Property Right: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Nankai Business Review 5: 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Zhenghua, and Jia Chen. 2015. Cash Dividend Policy and Effect of Private Placement Announcement. Finance and Accounting Monthly 15: 115–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciukaityte, Dalia, Samuel H. Szewczyk, and Raj Varma. 2005. Investor Overoptimism and Private Equity Placements. Journal of Financial Research 28: 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Stewart C., and Nicholas S. Majluf. 1984. Corporate Financing and Investment Decisions When Firms Have Information That Investors Do Not Have. Journal of Financial Economics 13: 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Yuping, and Rohaya Binti Abdul Jalil. 2023. Private Placement of China-Listed Real Estate Firms: A Conceptual Idea. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16: 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoff, Kenneth, and Yuanchen Yang. 2021. Has China’s housing production peaked? China World Economy 29: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Jinyan, Conghui Yu, Sicen Guo, and Yanxi Li. 2020. Market Effects of Private Equity Placement: Evidence from Chinese Equity and Bond Markets. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 53: 101214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, He, Yao Li, and Yu Long. 2019. Does Venture Capital Affect the Underpricing Rate of Listed Companies’ Private Placement? Journal of Finance and Economics 45: 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Pengcheng. 2014. Private Placement of Public Equity in China. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Xin, Xiaodi Liu, and Huiyu Chen. 2024. Driving force of value reversal in Chinese overleveraged firms: The mechanism and path of private placement. PLoS ONE 19: e0303544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Dianbo. 2015. An Empirical Study on the Effect of Private Placement Announcements of Listed Companies in China. Times Finance 33: 143–59. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Ruth S. K., Pheng L. Chng, and Y. H. Tong. 2002. Private placements and rights issues in Singapore. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 10: 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Qizhi, Zhao Zhao, Mingming Zhang, and Xueman Xiang. 2018. Managerial Placement and Entrenchment. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 54: 3366–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veld, Chris, Patrick Verwijmeren, and Yuriy Zabolotnyuk. 2020. Wealth Effects of Seasoned Equity Offerings: A Meta-Analysis. International Review of Finance 20: 77–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Huacheng, Jinzhao Liu, Shenghao Gao, and Xiaoquan Qing. 2020. Tunneling or Signaling? An Analysis on Big Shareholder Participation and SEO Discount. Management Review 32: 266–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wruck, Karen Hopper. 1989. Equity ownership concentration and firm value: Evidence from private equity financings. Journal of Financial Economics 23: 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]