Flexible Use of the Large-Scale Short-Time Work Scheme in Germany during the Pandemic: Dynamic Labour Demand Models Estimation with High-Frequency Establishment Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Institutional Background and Previous Literature

- (1)

- The entitlement period was prolonged, so that the STW allowances could be paid for a maximum of 24 months.

- (2)

- Social security contributions for the lost working hours were covered by the labour agency from the first month.

- (3)

- The replacement rate was raised to 70 percent for employees without children and 77 percent for employees with children beginning in the fourth month of STW, and to 80 percent and 87 percent, respectively, from the seventh month.

- (4)

- Employees with temporary contracts became eligible.

- (1)

- The extension of the period during which the STW allowance could be paid was from 12 months to up to 24 months ending 31 December 2021 at the latest only for those establishments that had introduced STW by 31 December 2020.

- (2)

- Full reimbursement of social insurance contributions was possible until June 2021, followed by reimbursement of half of the amount until 31 December 2021.

- (3)

- Increased STW allowance after the fourth and the seventh month, if the loss of work was at least 50 percent and STW had been introduced by 31 March 2021.

- (4)

- Possibility of supplementary earnings, e.g., through part-time work, up to the normal pay level until 31 December 2021 (Bellmann et al. 2020).

- (5)

- Skills development during STW was made more attractive for the employers.

3. Data

4. Theory

5. Descriptive Analysis and Empirical Model

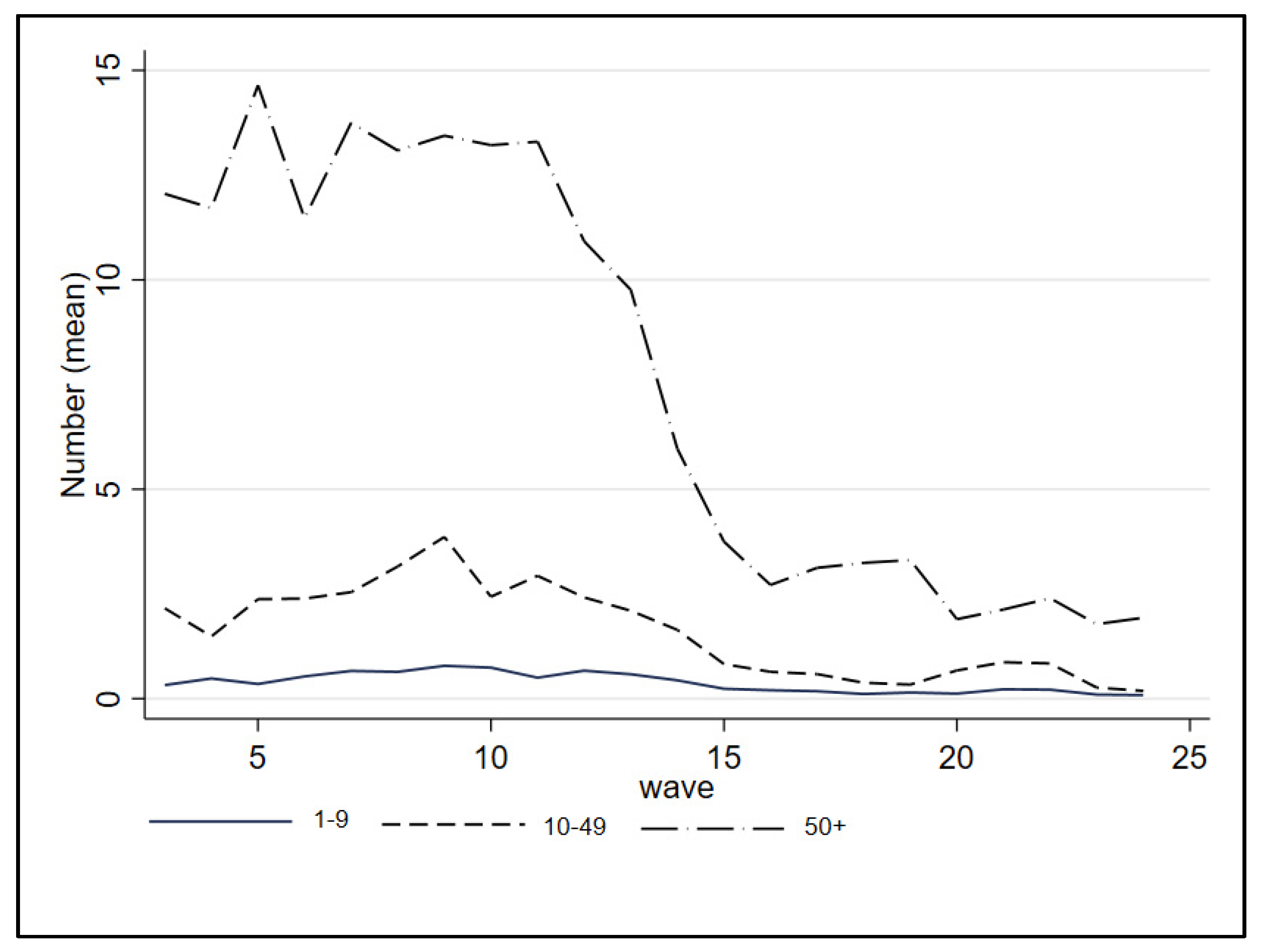

5.1. Descriptive Analysis

5.2. Empirical Model

6. Results

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The estimation results without the use of robust standard errors are statistically significant in each case. However, the small values rather indicate a small influence. The p-values for robust standard errors are 0.2 in each case. The estimation results are available from the authors on request. |

References

- Abowd, John, and Francis Kramarz. 2003. The costs of Hiring and Separations. Labour Economics 10: 499–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, John, Pedro Portugal, and Jose Varejão. 2014. Labor Demand Research: Toward a Better Match Between Better Theory and Better Data. Labour Economics 30: 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, Manuel, and Olympia Bover. 1995. Another Look at the Instrumental Variable Estimation of Error-Components Models. Journal of Econometrics 68: 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, Manuel, and Stephen Bond. 1991. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies 58: 277–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, Nils, Lutz Bellmann, Patrick Gleiser, Sophie Hensgen, Christian Kagerl, Theresa Koch, Corinna König, Eva Kleifgen, Moritz Kuhn, and Ute Leber. 2021. Panel “Establishments in the COVID-19 Crisis”—20/21. A Longitudinal Study in German Establishments—Waves 1–14. FDZ Data Report 13/2021. Nuremberg: Institute for Employment Research. [Google Scholar]

- Balleer, Almut, Britta Gehrke, Wolfgang Lechthaler, and Christian Merkl. 2016. Does Short-Time Work Save Jobs? A Business Cycle Analysis. European Economic Review 84: 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmann, Lutz, and Anke Jenckel. 2020. Short-Time Work in Germany: Dynamics and Regulations. Presentation Prepared for the OECD-IAB Webinar “Job Retention Schemes during the COVID-19 Lockdown and beyond, 20 November 2020. Available online: https://iab.de/en/iab-veranstaltungen/job-retention-schemes-during-the-covid-19-lockdown-and-beyond-2/ (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Bellmann, Lutz, Andreas Crimmann, Hans-Dieter Gerner, and Frank Wiessner. 2013. Work Sharing as an Alternative to Layoffs: Lessons from the German Experience During the Crisis. In Work Sharing During the Great Recession. Edited by J. C. Messenger and N. Ghosheh. Cheltenham and Geneva: Edward Elgar and International Labour Office, pp. 24–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bellmann, Lutz, Hans-Dieter Gerner, and Marie-Christine Laible. 2016. The German Labour Market Puzzle in the Great Recession. In Productivity Puzzles Across Europe. Edited by Philippe Askenazy, Lutz Bellmann, Aalex Bryson and Eva Moreno Galbis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 187–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bellmann, Lutz, Patrick Gleiser, Christian Kagerl, Theresa Koch, Corinna König, Thomas Kruppe, Julia Lang, Ute Leber, Laura Pohlan, Duncan Roth, and et al. 2020. Weiterbildung in der COVID-19-Pandemie stellt viele Betriebe vor Schwierigkeiten. IAB-Forum. December 9. Available online: https://www.iab-forum.de/weiterbildung-in-der-covid-19-pandemie-stellt-viele-betriebe-vor-schwierigkeiten/ (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Bellmann, Lutz, Patrick Gleiser, Sophie Hensgen, Christian Kagerl, Ute Leber, Duncan Roth, Matthias Umkehrer, and Jens Stegmaier. 2022. Establishments in the COVID-19-Crisis (BeCOVID): A high-frequency establishment survey to monitor the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 242: 421–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, and Stephen Bond. 1998. Initial Conditions and Moment Restrictions in Dynamic Panel Data Models. Journal of Econometrics 87: 115–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeri, Tito, and Herbert Bruecker. 2011. Short-Time Work Benefits Revisited: Some Lessons from the Great Recession. Economic Policy 26: 697–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, Ricardo, Eduardo Engel, and John Haltiwanger. 1997. Aggregate Employment Dynamics: Building from Microeconomic Evidence. American Economic Review 87: 115–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cahuc, Pierre, and Sandra Nevoux. 2019. Inefficient Short-Time Work. Science Po Economics Discussion Paper No. 2019-03. Paris: Sciences Po Department of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Cahuc, Pierre, Fabien Postel-Vinay, and Jean-Marc Robin. 2006. Wage Bargaining with On-The-Job Search: Theory and evidence. Econometrica 74: 323–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahuc, Pierre, Francis Kramarz, and Sandra Nevoux. 2018. When Short-Time Work Works. IZA Discussion Paper No. 11373. Bonn: The Institute for Labor Economics (IZA). [Google Scholar]

- Cahuc, Pierre, Francis Kramarz, and Sandra Nevoux. 2021. The Heterogeneous Impact of Short-Time Work From Saved Jobs to Windfall Effects. IZA Discussion Paper No. 14381. Bonn: The Institute for Labor Economics (IZA). [Google Scholar]

- Cahuc, Pierre, Stephane Carcillo, and Andre Zylberberg. 2014. Labor Economics. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonero, Francesco, and Hermann Gartner. 2022. A Note on The Relation Between Search Costs And Search Duration For New Hires. Macroeconomic Dynamics 26: 263–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Russell, Moritz Meyer, and Immo Schott. 2017. The Employment and Output Effects of Short-Time Work in Germany. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 23688. Boston: The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). [Google Scholar]

- Crimmann, Andreas, Frank Wießner, and Lutz Bellmann. 2012. Resisting the Crisis: Short-Time Work in Germany. International Journal of Manpower 33: 877–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destatis. 2022. Veränderungen des Bruttoinlandsprodukts (BIP) in Deutschland gegenüber dem Vorquartal (preis-, saison-und kalenderbereinigt) vom 2. Quartal 2018 bis 2. Quartal 2022, Wiesbaden. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2022/07/PD22_322_811.html (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Federal Employment Services. 2022. Monatsbericht zum Arbeits- und Ausbildungsmarkt, Nuremberg June 2022. Available online: https://www.arbeitsagentur.de/datei/arbeitsmarktbericht-dezember-2022_ba147806.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Fitzenberger, Bernd, and Ulrich Walwei. 2023. Kurzarbeitergeld in der COVID-19-Pandemie: Lessons Learned. Forschungsbericht 5/2023. Nuremberg: Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (IAB), Institute for Employment Research. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzenbeger, Bernd, Christian Kagerl, Malte Schierholtz, and Jens Stegmaier. 2021. Realtime Economic Data in The COVID-19-Crisis: On the Difficulty Of Measuring Short-Time Work. IAB-Kurzbericht 24/2021. Nuremberg: Institut für Ar-beitsmarkt-und Berufsforschung (IAB). [Google Scholar]

- Ganzer, Andreas, Lisa Schmidtlein, Jens Stegmaier, and Stefanie Wolter. 2021. Establishment History Panel 1975–2019. FDZ Data Report 16/2020 EN. Nuremberg: Research Data Centre (FDZ) of the German Federal Employment Agency (BA) at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB). [Google Scholar]

- Hamermesh, Daniel. 1989. Labor Demand and the Structure of Adjustment Costs. American Economic Review 79: 674–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hamermesh, Daniel. 1993. Labor Demand. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hijzen, Alexander, and Danielle Venn. 2011. The Role of Short-time Work Schemes during the 2008–09 Recession. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund. 2020. Kurzarbeit: Germany’s Short-Time Work Benefit. Washington, DC: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Sven. 2014. Employment Adjustment in German Firms. Journal for Labour Market Research 47: 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konle-Seidl, Regina. 2020. Short-Time Work in Europe: Rescue in the Current COVID-19-Crisis. Nuremberg: IAB-Forschungsbericht, Institut für Arbeitsmarkt-und Berufsforschung (IAB). [Google Scholar]

- Kramarz, Francis, and Marie-Laure Michaud. 2010. The Shape of Hiring and Separation Costs in France. Labour Economics 17: 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripfganz, Sebastian, and Claudia Schwarz. 2019. Estimation of Linear Dynamic Panel Data Models with Time-Invariant Regressors. Journal of Applied Econometrics 34: 526–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, Alan. 2006. A Generalised Model of Monopsony. The Economic Journal 116: 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosley, Hugh, and Thomas Kruppe. 1996. Employment Stabilization through Short-time work. In International Handbook of Labour Market Policy and Evaluation. Edited by G. Schmid, J. O’Reilly and K. Schömann. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 594–622. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley, Hugh, Thomas Kruppe, and Stefan Speckesser. 1995. Flexible Adjustment through Short-Time Work: A Comparison of France, Germany, Italy and Spain. WZB Discussion Paper FSI 95-206. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, Øivind, Kjell Salvanes, and Fabio Schiantarelli. 2007. Employment Changes, the Structure of Adjustment Costs, and Plant Size. European Economic Review 51: 577–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2020. Job Retention Schemes during the COVID-19 Lockdown and Beyond. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2021. OECD Employment Outlook 2021: Navigating the COVID-19 Crisis and Recovery. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2022. OECD Employment Outlook 2022: Building Back More Inclusive Labour Markets. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Roodman, David. 2009. A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 71: 135–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Günther. 2022. Kurzarbeit im Korsett der Versicherungslogik: Es ist Zeit die “Bazooka“ neu zu justieren. In Sozioökonomik der Corona-Krise. Edited by Lutz Bellmann and Wenzel Matiaske. Marburg: Ökonomie und Gesellschaft, vol. 33, pp. 335–50. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, Theresa, Christian Sprenger, and Stefan Bender. 2011. Kurzarbeit in Nürnberg: Beruflicher Zwischenstopp oder Abstellgleis? IAB-Kurzbericht 15/2011. Nürnberg: Institut für Arbeitsmarkt-und Berufsforschung (IAB). [Google Scholar]

- Varejão, Jose, and Pedro Portugal. 2007. Employment dynamics and the structure of labor adjustment costs. Journal of Labor Economics 25: 137–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vom Berge, Philipp, Corinna Frodermann, Andreas Ganzer, and Alexandra Schmucker. 2021. Sample of Integrated Labour Market Biographies, Regional Life (SIAB-R) 1975–2019. FDZ Data Report 05/2021. Nuremberg: Research Data Centre (FDZ) of the German Federal Employment Agency (BA) at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB). [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Enzo, and Yasemin Yilmaz. 2023. Designing Short Time Work for Mass Use. European Journal of Social Security 25: 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windmeijer, Frank. 2005. A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. Journal of Econometrics 126: 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of workers (log.) | 45,852 | 3.289081 | 1.548164 | 0 | 11.35041 |

| Average daily wage 2020 (log.) | 39,670 | 4.531232 | 0.3603016 | 2.152924 | 6.67605 |

| Share of unskilled workers | 43,996 | 0.1448739 | 0.2092642 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of short-time workers | 42,463 | 4.585333 | 29.10596 | 0 | 2000 |

| Short-time work (=1) | 7382 | 0.172917 | 0.3781799 | 0 | 1 |

| Supply of goods and services | |||||

| Exclusively or mainly within Germany | 39,761 | 0.8807008 | 0.3241438 | 0 | 1 |

| Mainly outside Germany | 1360 | 0.0301238 | 0.1709299 | 0 | 1 |

| In equal parts within and outside Germany | 4026 | 0.0891754 | 0.2849999 | 0 | 1 |

| Foreign ownership (=1) | 2692 | 0.0591752 | 0.235955 | 0 | 1 |

| Works council (=1) | 9986 | 0.2179921 | 0.4128865 | 0 | 1 |

| Liquidity (duration until insolvency) | |||||

| 1 to 2 weeks | 530 | 0.0130071 | 0.1133059 | 0 | 1 |

| up to 4 weeks | 1761 | 0.0432179 | 0.2033498 | 0 | 1 |

| up to 2 months | 5068 | 0.1243773 | 0.3300155 | 0 | 1 |

| up to 6 months | 7821 | 0.1919405 | 0.3938314 | 0 | 1 |

| up to 12 months | 3879 | 0.0951972 | 0.2934907 | 0 | 1 |

| sufficient reserve | 21,688 | 0.53226 | 0.4989643 | 0 | 1 |

| Industry | |||||

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 672 | 0.0136393 | 0.1159896 | 0 | 1 |

| Mining and quarrying | 56 | 0.0012182 | 0.0348816 | 0 | 1 |

| Manufacturing industries | 7881 | 0.1714379 | 0.3768953 | 0 | 1 |

| Energy supply | 124 | 0.0026974 | 0.0518671 | 0 | 1 |

| Water supply | 257 | 0.0055906 | 0.0745618 | 0 | 1 |

| Construction | 3718 | 0.0808788 | 0.2726519 | 0 | 1 |

| Trade and maintenance | 8671 | 0.188623 | 0.3912131 | 0 | 1 |

| Transportation and storage | 1733 | 0.0376985 | 0.1904681 | 0 | 1 |

| Hospitality industry | 2165 | 0.0470959 | 0.2118464 | 0 | 1 |

| Information and communication | 1373 | 0.0298673 | 0.170223 | 0 | 1 |

| Financial and insurance services | 1001 | 0.0217751 | 0.1459499 | 0 | 1 |

| Real estate activities | 441 | 0.0095932 | 0.0974751 | 0 | 1 |

| Professional, scientific and technical serv. | 4171 | 0.0907331 | 0.2872323 | 0 | 1 |

| Other scientific services | 3373 | 0.0733739 | 0.2607521 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | 1508 | 0.032804 | 0.1781252 | 0 | 1 |

| Health and social work | 6484 | 0.1410485 | 0.3480754 | 0 | 1 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 513 | 0.0111595 | 0.1050484 | 0 | 1 |

| Other services | 1874 | 0.0407657 | 0.1977491 | 0 | 1 |

| Impact of COVID-19 on business activities | |||||

| Very strongly negative −5 | 3696 | 0.0842163 | 0.2777151 | 0 | 1 |

| −4 | 5074 | 0.1156151 | 0.3197664 | 0 | 1 |

| −3 | 6006 | 0.1368515 | 0.3436944 | 0 | 1 |

| −2 | 2892 | 0.0658965 | 0.2481039 | 0 | 1 |

| −1 | 907 | 0.0206667 | 0.1422676 | 0 | 1 |

| Balanced/neither nor 0 | 22,180 | 0.5053888 | 0.4999767 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 175 | 0.0039875 | 0.0630215 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 409 | 0.0093194 | 0.0960872 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 1076 | 0.0245175 | 0.1546511 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 992 | 0.0226035 | 0.1486374 | 0 | 1 |

| Very strongly positive 5 | 480 | 0.0109372 | 0.1040087 | 0 | 1 |

| Establishment size | |||||

| 1 to 9 employees | 13,503 | 0.293735 | 0.455477 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 to 49 employees | 14,107 | 0.306874 | 0.4612017 | 0 | 1 |

| 50 to 249 employees | 14,665 | 0.3190124 | 0.4660989 | 0 | 1 |

| 250+ employees | 3695 | 0.0803785 | 0.2718812 | 0 | 1 |

| (a) Employment Incl. STW | (b) Employment Incl. STW | (c) Employment Incl. STW | (d) Employment Excl. STW | (e) Employment Excl. STW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log. of lagged endogenous variable (t − 1) | 0.775 ** (0.062) | 0.741 ** (0.069) | 0.768 ** (0.056) | 0.228 * (0.090) | 0.260 ** (0.099) |

| Interaction variable: Log. of lagged endogenous variable (t − 1) × (use of STW, no. of STW) | 0.002 (0.001) | −0.009 * (0.004) | |||

| Interaction variable: Log. of lagged endogenous variable (t − 1) × (use of STW, yes = 1, no = 0) | 0.008 (0.008) | −0.250 * (0.113) | |||

| Log. of average daily remuneration in 2020 | 0.053 ** (0.017) | 0.065 ** (0.020) | 0.055 ** (0.016) | 0.187 ** (0.056) | 0.181 ** (0.067) |

| Share of unskilled workers | 0.107 ** (0.034) | 0.122 ** (0.037) | 0.109 ** (0.031) | 0.367 ** (0.110) | 0.253 * (0.125) |

| Supply of goods and services… (base: exclusively or predominantly within Germany) | |||||

| Predominantly outside Germany | 0.015 (0.014) | 0.011 (0.015) | 0.016 (0.015) | 0.065 (0.050) | 0.090 (0.059) |

| In roughly equal parts within and outside Germany | 0.029 ** (0.011) | 0.029 * (0.012) | 0.028 * (0.011) | 0.044 (0.046) | 0.089 (0.057) |

| Predominantly in foreign ownership | −0.026 (0.016) | −0.027 (0.018) | −0.026 (0.017) | −0.071 (0.066) | −0.114 (0.076) |

| Works council | 0.054 ** (0.017) | 0.060 ** (0.018) | 0.054 ** (0.015) | 0.134 ** (0.040) | 0.135 ** (0.046) |

| Impact of the Corona pandemic on business activities (10 dummies) # | yes * | yes | yes | yes ** | yes ** |

| Liquidity (5 dummies) ## | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Dummies indicating industries (18 dummies) | yes | yes | yes | yes ** | yes ** |

| Dummies indicating firm size (3 dummies) | Yes ** | Yes ** | Yes ** | yes ** | yes ** |

| No. of observations (firms; instruments) | 16,169 (6547; 188) | 14,882 (6148; 271) | 14,951 (6167; 267) | 14,832 (6133; 271) | 14,832 (6133; 267) |

| Wald test χ2 (df.) | 256,740.53 ** (64) | 226,025.24 ** (63) | 227,057.01 ** (63) | 14,810.92 ** (63) | 11,454.93 ** (63) |

| First order (z-value) | −3.8511 ** | −3.3483 ** | −3.553 ** | 3.3222 ** | 2.5863 ** |

| Second order (z-value) | 1.2632 | 1.3527 | 1.3893 | −0.0745 | −0.4514 |

| (a) Employment Incl. STW | (b) Employment Incl. STW | (c) Employment Excl. STW | (d) Employment Excl. STW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log. of lagged endogenous variable (t − 1) | 0.816 ** (0.056) | 0.804 ** (0.053) | 0.260 ** (0.063) | 0.337 ** (0.118) |

| Interaction variable: Log. of lagged endogenous variable (t − 1)*(use of STW, yes = 1, no = 0) | 0.011 (0.010) | −0.192 * (0.082) | ||

| Interaction variables: dummy indicating decreasing employment (endogenous variable) * | ||||

| Log. of lagged endogenous variable (t − 1) | 0.005 * (0.002) | 0.013 (0.007) | −0.038 (0.045) | −0.105 ** (0.010) |

| Interaction variable: Log. of lagged endogenous variable (t − 1)*(use of STW, yes = 1, no = 0) | −0.011 (0.012) | 0.144 (0.137) | ||

| No. of observations (firms; instruments) | 16,169 (6547; 257) | 14,951 (6167; 388) | 14,832 (6133; 237) | 14,832 (6133; 381) |

| Wald test χ2 (df.) | 327,778.57 ** (65) | 321,145.50 ** (65) | 15,109.70 ** (62) | 14,717.79 ** (65) |

| First order (z-value) | −3.8016 ** | −3.4141 ** | 3.7926 ** | −3.7435 ** |

| Second order (z-value) | 1.2271 | 1.3363 | −0.0586 | −0.0289 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bellmann, L.; Bellmann, L.; Kölling, A. Flexible Use of the Large-Scale Short-Time Work Scheme in Germany during the Pandemic: Dynamic Labour Demand Models Estimation with High-Frequency Establishment Data. Economies 2023, 11, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11070192

Bellmann L, Bellmann L, Kölling A. Flexible Use of the Large-Scale Short-Time Work Scheme in Germany during the Pandemic: Dynamic Labour Demand Models Estimation with High-Frequency Establishment Data. Economies. 2023; 11(7):192. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11070192

Chicago/Turabian StyleBellmann, Lisa, Lutz Bellmann, and Arnd Kölling. 2023. "Flexible Use of the Large-Scale Short-Time Work Scheme in Germany during the Pandemic: Dynamic Labour Demand Models Estimation with High-Frequency Establishment Data" Economies 11, no. 7: 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11070192

APA StyleBellmann, L., Bellmann, L., & Kölling, A. (2023). Flexible Use of the Large-Scale Short-Time Work Scheme in Germany during the Pandemic: Dynamic Labour Demand Models Estimation with High-Frequency Establishment Data. Economies, 11(7), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11070192