4. Results

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics of economic variables from 1990 to 2021. The

is found to have a mean of 2.06%. The level of

is found to have an average of 0.59% between 1979 and 2022. The

is found to have a mean of 0.16%. The

is found to have a rate of 6.64% over the period reflecting the mean. The

is found to be 11.56%, and the

is found to be 9.57% between 1990 and 2021 on average. The

is found to have a mean of 10.85%. The

is found to have a rate of 1.73% over the period reflecting the mean.

Table 3 shows the correlation between economic variables. Most of the economic variables of interest considered in the paper are found to have a positive correlation with

except

,

, and

. These results are similar to those of

Meyer et al. (

2018), who found a correlation value of 0.9742 between

and

. In this paper, there is 0.1704 between

and

.

Table 4 shows the Dickey–Fuller and Phillips–Perron tests for the unit root with the result that at a level, the unit root null hypothesis could not be rejected, as it was not stationary at the level for all economic variables considered except for

. All variables are found to have stationarity at first difference.

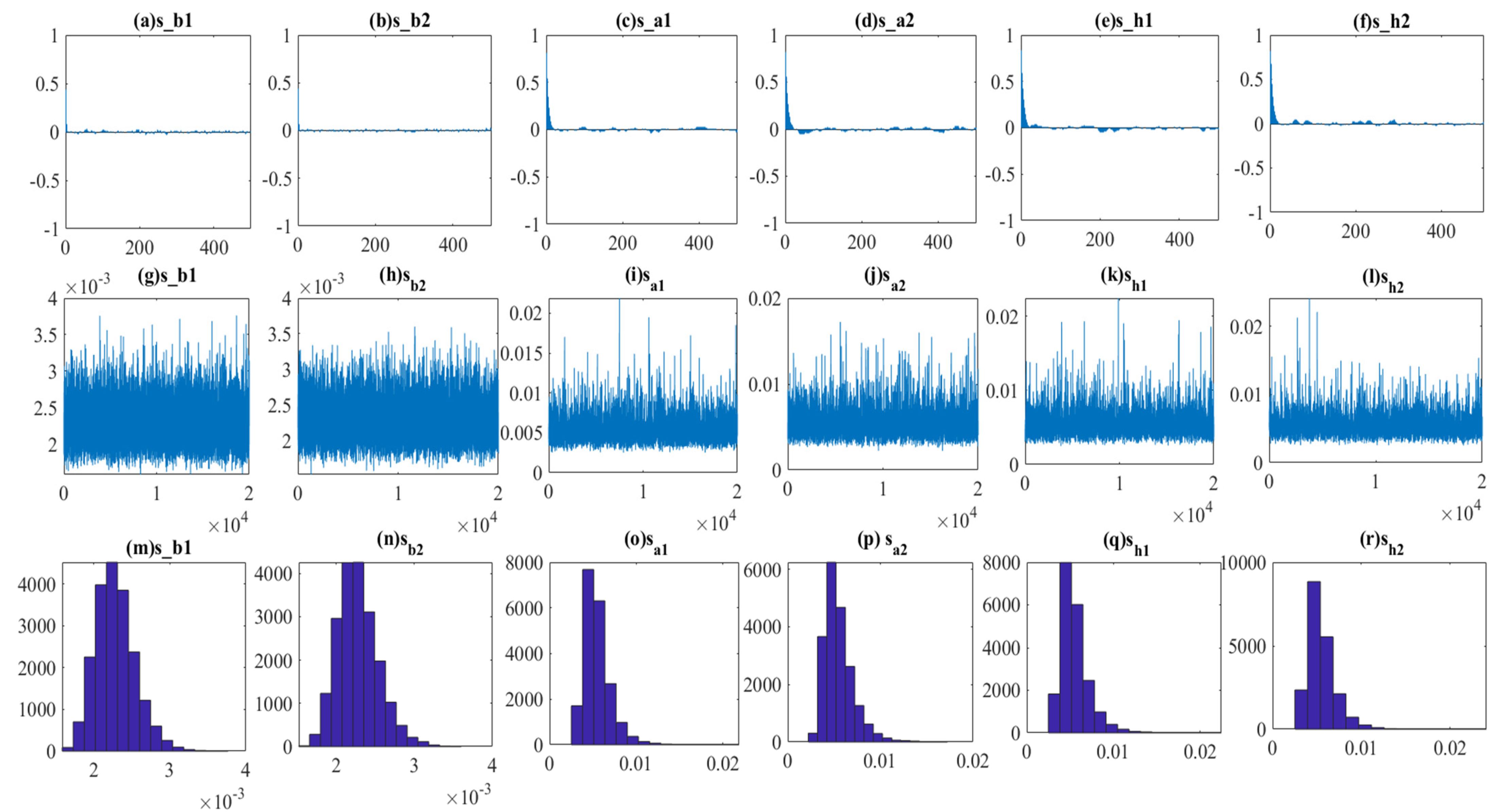

The TVP-VAR results are shown in

Table A1, which shows the posterior means, standard deviations, 95% credible intervals, convergence diagnostics (CD) of (

Geweke 1992), and inefficiency factors computed using the MCMC sample. The CD statistics are less than unity, and the inefficiency factors are less than 100. In the estimated result, the null hypothesis of convergence to the posterior distribution is not rejected for the parameters at the 5% significance level based on the CD statistics, and the inefficiency factors are quite low except for

, which indicates efficient sampling for the parameters and state variables.

Figure A1 and

Figure A2 show the sample autocorrelation function, the sample paths, and the posterior densities for the selected parameters. After discarding the initial 2000 samples in the burn-in period, the sample paths look stable, and the sample autocorrelations drop smoothly.

Table 5 reflects the Markov chain dynamic regression model for the gross domestic product from 1990 to 2021. The result is of interest to the estimation of the impact of money supply on economic growth in different states. In state 1, estimation 1,

is found to have a negative gross domestic product state mean

2 rate of 2.00%, which is statistically significant at a 5%

p-value. In estimation 4, it is found that a 1% increase in

results in a 0.70% fall in

holding all other factors constant, and it is statistically significant at a 5%

p-value. This implies that

in state 1 does not predict any positive effect on economic growth. The result is consistent with the theoretical assertion of Monetarists who assumed that money supply affects the price level, not the real GDP or unemployment level. South Africa cannot afford to be in this state of the economy, as it may not be able to fight other macroeconomic challenges of poverty, inequality, and unemployment. Moreover, this state of the economy will reflect that South Africa is far off in achieving the objective of the NDP of having an economic growth rate of 5%. Given that in this state there is negative growth output, an increase in the money supply may be detrimental as it can lead to much money chasing few goods. In a event of an increase in the price level. This would not be good for the general public as the wage sticks; therefore, the real wage will fall and affect aggregate consumption and the fall in the gross domestic product. In this, the increase in the money supply may have several negative multiplier effects. In state 2, estimation 1 of

is found to have a positive mean of 2.75%, which is statistically significant at a 1% p-value. In estimation 4, it is found that

is statistically insignificant at a 5%

p-value. This is in line with Keynesians’ view that the money supply has a limited influence on economic growth. However, when the monetary policy instrument of

is not factored in, it is found that there is a 1% increase in

and estimation 3 is found to increase

by 0.03%. This result suggests that in a positive economic growth state with less monetary policy through the interest rate, money may have a positive spillover on economic growth. These results are similar to those found by

Denbel et al. (

2016).

Table 6 reflects the Markov chain dynamic regression model from 1990 to 2021. The results are of interest to the estimation of the impact of money supply on inflation in different states. In state 1, estimation 1 of

is found to have a mean of 5.70%, which is statistically significant at a 1%

p-value. In estimation 4, it is found that a 1% increase in

results in a 0.05% fall in

holding all other factors constant, and it is statistically significant at a 5%

p-value. These results are similar to those of

Sean (

2019), who found that the money supply induces an inflation rate of 0.13%. State 1 inflation means is within the target of 3% to 6%, and the result implies that the monetary tool of the money supply is effective in stabilising prices when inflation is within range. In state 2, estimation 1 of

is found to have a mean of 13.24%, which is statistically significant at a 1%

p-value. In estimation 4, it is found that a 1% increase in

results in a 0.35% increase in

holding all other factors constant, and it is statistically significant at a 1%

p-value. This result suggests that the monetary instrument of the money supply is not effective in reducing the price level when the inflation rate is above the range of 3% to 6%.

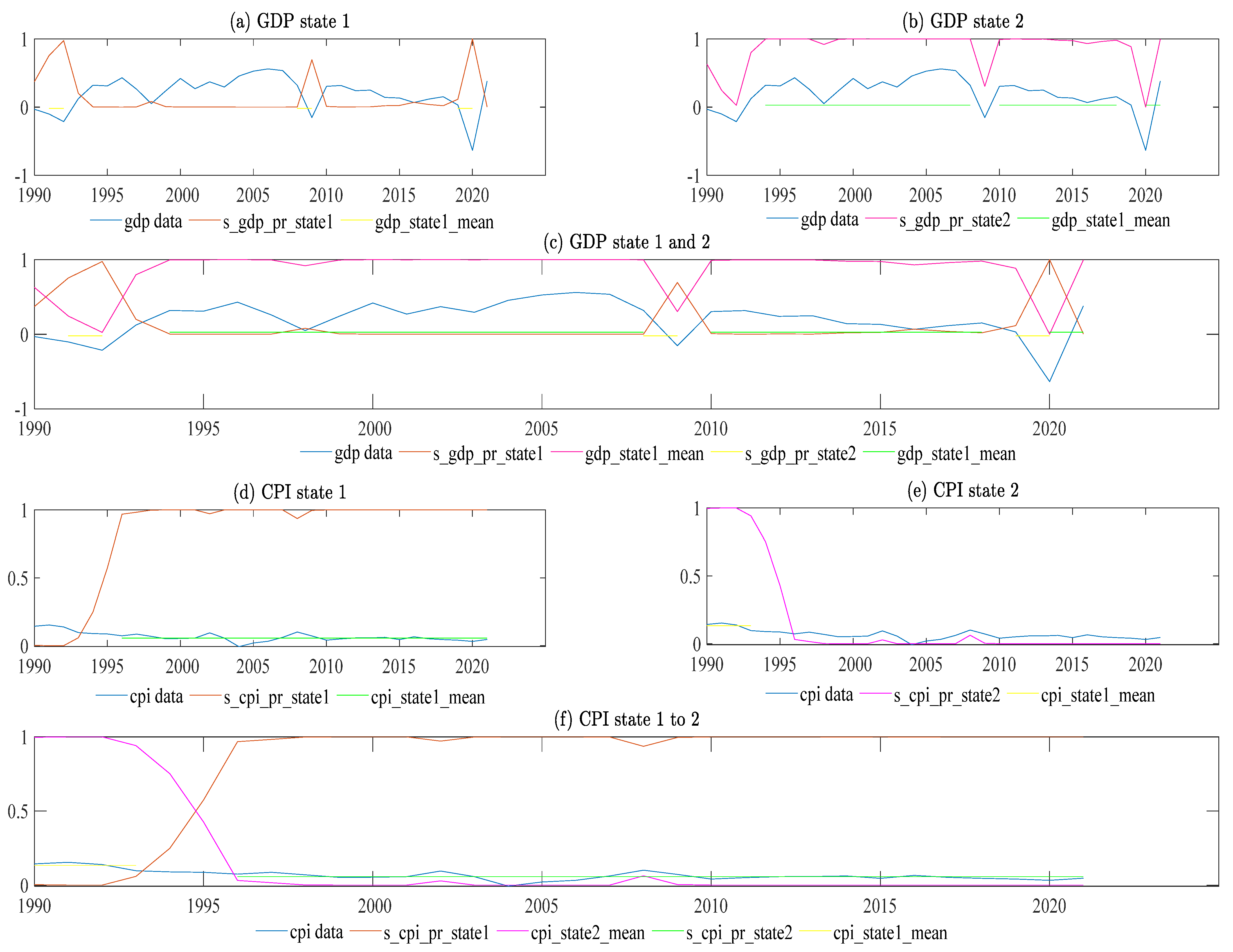

Figure 1 reflects state 1 to 2 filter transition probabilities and the data of

and

.

Figure 1 graph a reflects the filter transition probabilities for state 1 for

, which is characterised by a negative mean of 2.00%. The

is found to move to state one in two episodes, first in 1994 and second in 2019. This reflects that most of the time, South African economic growth is not prone to stay in a negative state. As such, the result reflects that the economy may recover faster in the occurrence of a recession.

Figure 1 graph b reflects the filter transition probabilities for state 2, which is characterised by a negative mean of 2.84%. It is found that the economy moved to this state three times. The economy was in state 2 from 1994 to 2008. The economy moved back to this state from 2010 to 2018, and the last move to this state was in 2021.

Figure 1 graph c reflects states 1 to 2 for

moving from state to state over time.

Figure 1 graph d reflects the filter transition probabilities for state 1 for

, which is characterised by a mean of 5.70%.

is found to move to state one from 1996 to 2021.

Figure 1 graph e reflects the filter transition probabilities for state 2, which is characterised by a negative mean of 13.24%. The economy moved to this state in 1993.

Figure 1 graph f reflects states 1 to 2 for

moving from state to state over time.

Table 7 shows the transition probabilities of the two states for both

and

. There is a 91% chance that

will move from state one and return to state one. However, there is a 93% chance that

will move from state two and return to state two. For

, there is an 84% chance that

will move from state one and return to state one. There is evidence that there is an 80% chance that

will move from state two and return to state two.

Table 8 reflects the expected duration to be spent in each state. It is found that

will be in state 1 for 11 years and spend 16 years in state 2. On the other hand,

is expected to be in state 1 for 6 years and 5 years in state 2.

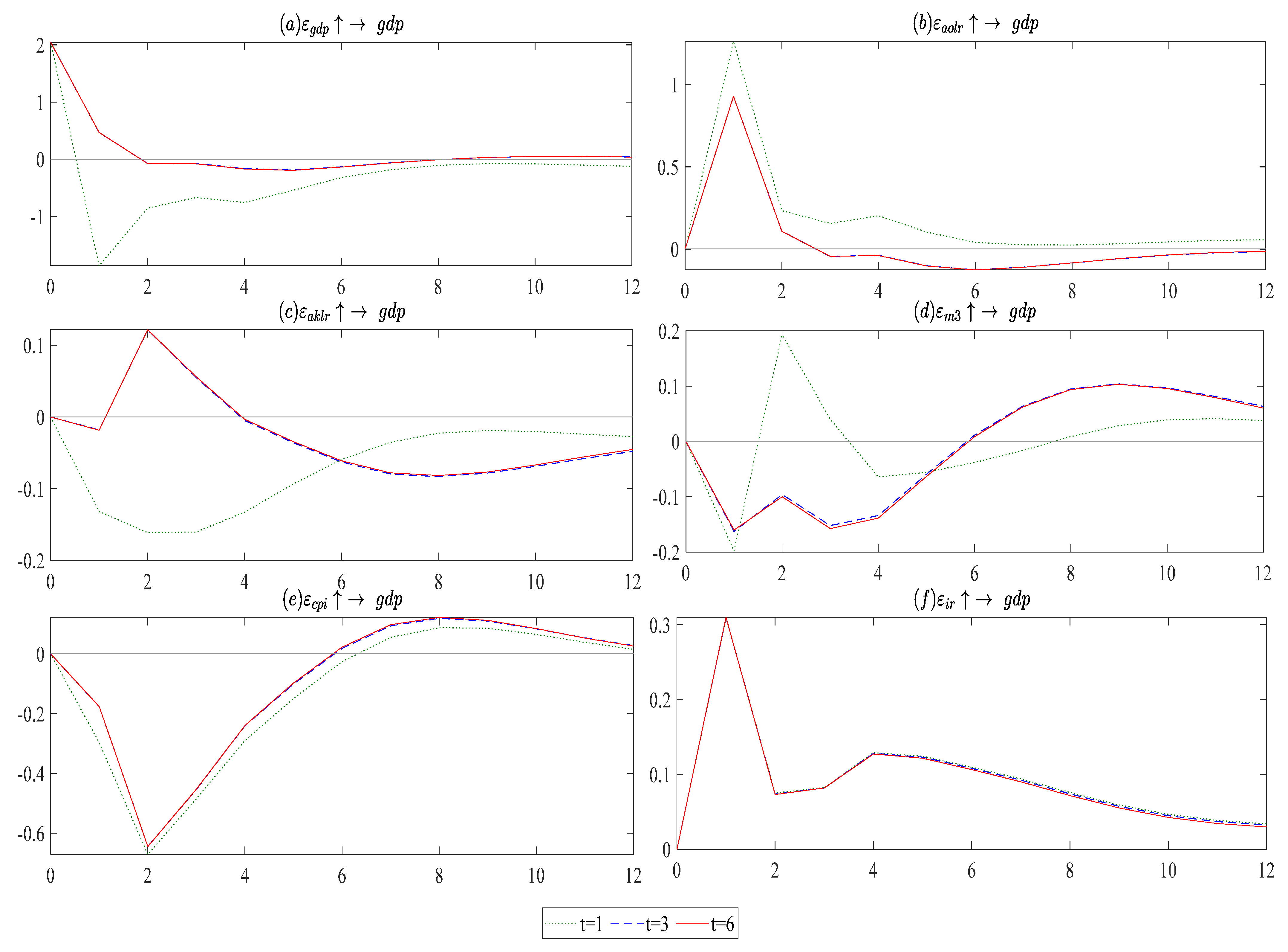

Figure 2 shows the time-varying posterior of impulse response shocks to gross domestic product. In

Figure 2, graph d, there is a reflection of the shock

of

to

. It is found that

shock results in a fall in the

in the first year by 0.15%. The

after that starts becomes to be cyclical with the increase rate to 1% and thereafter decreasing to 0.15%. In year 4 after the shock of

begins to increase until it reaches equilibrium levels in year 6. Thereafter,

operates above equilibrium with a maximum rate of 0.11%.

Figure 2, graph e, shows the impact of the shock

of

on

reflects the decrease in the

for two consecutive years with a negative rate of 0.1% and 0.6% in the respective first two years. The effect of high price levels in the economy state filters out as

increases from year 2 to 6. However, a 2-year decrease in

takes 4 years to recover after the shock of

.

increases until it reaches a maximum of 0.2% in year 8 and thereafter moderates down to 0.1%.

Figure 2, graph f, shows the shock

impact of

on

. The

reflects that there is a sharp increase in

to 0.3%, which is a historical value recorded compared to other shocks in

Figure 2. The sharp increase in year 1 is followed by a decrease in year 2, where

reaches a rate of 0.9%. There is a downwards trend thereafter as the shock filters out. Nevertheless, the GDP still operates above equilibrium.

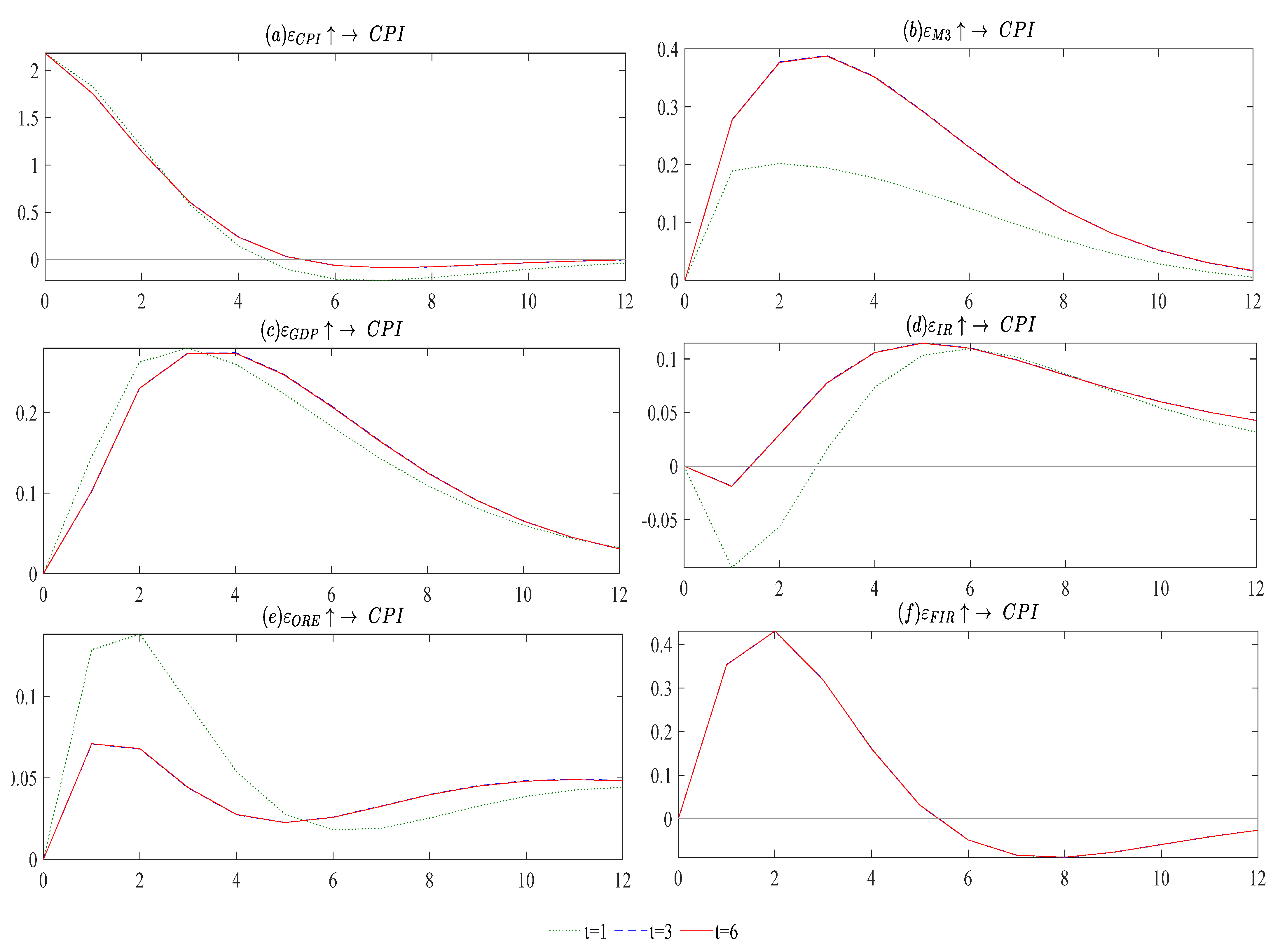

Figure 3 shows the time-varying posterior of impulse response shocks to inflation.

Figure 3, graph b, shows the shock

of

to

. It is found that

shock results in an increase in the

which is increasing at a decreasing rate up until it reaches the maximum of 0.39%. Thereafter, the shock filters out in year 12, which shows that it takes 9 years for the shock to filter out in the economic system.

Figure 3, graph c, shows the shock

of

to

. The result of the

shock to

is similar to the

shock to

with the difference in the magnitude, as the

results in an increase in

by 0.29% at the maximum reached in year 4 after the shock. The shock of the

after year 4 starts to filter out. However, the inflation rate operates above equilibrium. This reflects that there is no full recovery from high price levels when there is a positive shock in

.

Figure 3, graph c, shows the shock

of

to

. The

is one of the conventional monetary policy instruments. The positive shocks of

result in the desired result of a decrease in inflation. However, this decrease is marginal, with a rate of 0.03% in year 1 after the shock. Thereafter, inflation starts to increase until it reaches a maximum of 0.13% in year 5. After the maximum is reached, inflation moderates but operates above equilibrium.

5. Conclusions

This paper investigates the impact of the money supply on inflation and economic growth in South Africa from 1990 to 2021. The paper acknowledges that there are no censuses on the empirical and theoretical levels of the impact of money supply, inflation, and economic growth. The economic variable of interest, economic growth, is pretesting below the target of 5%, as is the National Development Plan, and the mean of the study period is 2.06%. On the other hand, inflation has reflected floatation, and in recent times, it has been in the high band of 6%. On the other hand, the rand value of the money supply, which is part of unconventional monetary policy, has increased over the years. The key economic question of this paper is as follows: what is the impact of money supply on economic growth and inflation in a different state? Therefore, the sub-questions are as follows: What is the probability of economic growth and inflation moving from state to state? How long will economic growth and inflation be in a state? What is the time-varying elasticity impact of money supply on economic growth and inflation in different states? What is the impact of money shocks on economic growth and inflation?

The theoretical framework of Cobb–Douglas was used to investigate the impact of the money supply on economic growth. On the other hand, the classical quantity theory of money was used to investigate the impact of the money supply on inflation. Markov-switching dynamic regression (MSDRM) and time-varying parameter structural vector autoregression (TVP-VAR) were adopted for estimation. There are two states for economic growth found, one with a negative rate of 2.00% and the other with a positive rate of 2.75%. There is a 91% and 93% chance that the economy can move and return to the same state both in states one and two. Currently, South Africa is in a positive state, which increases optimism that the money supply can further be used as an instrument to increase economic growth to meet the macroeconomic objectives outlined in the NDP to achieve 5% economic growth. However, given the high chance of staying in a negative state as well, the money supply has a negative impact on economic growth. This reflects that South Africa’s economy is fragile, and monetary tools may not be accommodative in the effort to restore aggregate demand. In such an event, South Africa will likely have a recession and monetary policy may not be fully effective in assisting the economy in recovery.

Similarly, inflation is found to have two states characterised by a mean rate of 5.70% and 13.24% with 84% and 80% changes in moving and returning to states 1 and 2, respectively. State one is better since it reflects a mean that is within the range of the inflation target of 3% to 6%. Moreover, the money supply is found to reduce inflation, which reflects the effectiveness of monetary policy in reducing inflation. Based on the results, monetary policy should be planned to maintain price stability by controlling the growth of the money supply in the economy. State two reflects the time when the SARB was not under inflation targeting. If the economy reaches this state the money supply is not effective in reducing inflation, as it results in a 0.35% increase in the inflation rate.

Money supply has a prime impact on economic growth, and money supply shocks are found to have a negative impact on gross domestic product. However, the money eventually moves economic growth above equilibrium in year 8. This, therefore, implies that monetary policy instruments play an important role in output growth and other macroeconomic policies in the long run. As such, it is recommended that the money supply be used for the long-run plan rather than the short-run plan. The estimated money supply reflected that there would be an increase in the inflation rate. Therefore, it implies that monetary expansion has continued as the key contributing factor to the persistent increase in the price level in South Africa. The stability of the overall price level will be impacted by the money supply; thus, South African monetary authorities need to exert stronger control over it. This will assist in avoiding inflation by moving to the economic state that is 2 times above the higher band inflation target.