Abstract

The relationship between trade openness and unemployment in Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries remains an area of significant interest and concern. While trade openness is often advocated for fostering economic growth and development, its potential effects on employment outcomes are complex and multifaceted. Understanding the nature and nuances of this relationship within the SADC region is crucial for policymakers and stakeholders seeking to design effective strategies that balance the benefits of trade openness with the goals of reducing unemployment and promoting inclusive growth. This study evaluates the effect of trade openness on unemployment in SADC from 1980 to 2019 using panel ARDL (pooled mean group—PMG) estimation techniques. The findings of the study show that trade openness and exports negatively impact unemployment, whereas imports positively affect unemployment in the long run. This suggests that while boosting exports and real trade, openness decreases unemployment, and imports increase job losses in the long run in the SADC region. This calls for more caution on trade openness regarding what to export and import when addressing regional unemployment reduction policies.

JEL Classifications:

E24; F16; F63

1. Introduction

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries, comprising a diverse group of nations in the southern region of Africa, have experienced a significant increase in trade openness as they actively participate in regional and international trade agreements (World Bank 2020a). This rise in trade openness has sparked concerns regarding its potential effects on unemployment rates within the region. Unemployment remains a persistent socioeconomic challenge in many SADC countries, impeding their development efforts and exacerbating social disparities (ILO 2020). Thus, exploring the intricate relationship between trade openness and unemployment in SADC countries is imperative. By understanding this relationship comprehensively, policymakers can devise effective strategies to address unemployment challenges and capitalise on the benefits of trade integration. This study aims to investigate the impact of trade openness on unemployment in selected SADC countries, contributing valuable insights to both academic discourse and policymaking to formulate evidence-based policies and interventions.

According to comparative advantage (Ricardo 1817) and HOS (Heckscher and Ohlin 1991), theorists, analysts and other empirical studies (Felbermayr et al. 2011; Fugazza et al. 2014; Belenkiy and Riker 2015), trade openness is a critical factor in reducing unemployment because it accelerates resource allocation, boosts productivity and increases competitiveness. Developed and developing countries have utilised foreign policies to increase productivity and job development (Steven and Evangelina 2013; Spohr and Silva 2017). As a result, many countries have enhanced trade openness. Even while their levels of trade openness are expanding, most countries, particularly developing economies such as the Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries, continue to face unemployment problems (SADC 2014; Kpognon et al. 2020; SADC Secretariat 2020).

The subject of this study is becoming more critical in light of the spread of unemployment. The SADC unemployment rate is still high (12.2%), regardless of the developmental target strategies (such as the Structural Adjustment Plan) implemented so far (ILO 2020; Motsatsi 2019; SADC Secretariat 2020). It is believed that unemployment and lack of jobs increase the chances of idleness, destitute, social crime, risk of poverty through loss of income and long-term unemployment, high population growth and income-earning disparities (Saunders 2002; Msigwa and Kipesha 2013; Mahmood et al. 2014; Motsatsi 2019).

Several factors, including population size, education levels, migration, technological advancements, global market trends and government policies, influence the labour market in SADC countries (Motsatsi 2019; ILO 2020; SADC Secretariat 2020). Thus, the current paper emphasises trade openness, which affects global market patterns and technology diffusion, affecting the labour markets (Kim et al. 2017; Belmonte et al. 2021). High unemployment in the region has been exacerbated by countries such as Zambia (13%), Botswana (19%), Namibia (21%), Eswatini (24%), South Africa (24%) and Lesotho (30%), which recorded high rates of unemployment since 1980 to 2019. Again, the countries (Botswana (57%), Eswatini (57.4%), Namibia (64.4%), Lesotho (72.7%) and South Africa, the economic hub of Southern Africa) that performed well in terms of trade openness have recorded high unemployment rates (averaging 20.8%) between 1980 and 2019 (World Bank 2020b).

Following high unemployment rates amid trade openness, the relationship between trade openness and unemployment has always been contentious. Other studies (Gozgor 2014; Anjum and Perviz 2016) suggest trade openness as a factor in reducing unemployment, while others (Kim 2011; Nwaka et al. 2015; Motsatsi 2019) disagree. For example, Barro and Sala-i-Martin (1997) opine that trade openness eliminates unemployment. It creates incentives that boost productivity through the efficient allocation of resources due to comparative advantage. Nonetheless, Davis (1998), Egger and Kreickemeier (2008) and Helpman and Itskhoki (2010) argue that trade openness exacerbates unemployment. The SADC Trade Protocol, Free Trade Area as well as the regional indicative strategic development plan (RISDP) aimed at increasing integration and trade openness amongst the SADC countries and outside the region to improve economic growth as well as to promote the creation of employment and decent work within the SADC region (SADC Secretariat 2003). Therefore, it is crucial to assess the determinants of unemployment, especially when developing economies such as SADC countries are becoming more open to international trade. This could significantly improve the SADC trade openness and unemployment reduction policies. Again, policymakers will benefit from this research by adapting their unemployment reduction and trade strategies to better manage the unemployment gap across the SADC countries. The paper utilised panel data from 1980 to 2019 for 16 SADC countries to achieve the study objectives.

The current paper examines whether trade openness reduces unemployment and contributes to the understanding of influential unemployment determinants in SADC countries only. The specific objectives of the study are (a) to specify the employment model; (b) to econometrically analyse the impact of real trade openness on unemployment; (c) to econometrically examine the effect of exports and imports on unemployment in SADC countries separately and (d) to make policy recommendations based on the findings of the study.

Given the above objectives, the current study tested the following hypotheses: : Trade openness does not reduce unemployment in SADC countries. : Trade openness reduces unemployment in SADC countries. The findings of the study show that trade openness and exports negatively impact unemployment, whereas imports positively affect unemployment in the long run. The results are robust to all forms of trade openness used in the paper.

The study reviews the existing literature on trade openness and unemployment in Section 2. Section 3 presents the unemployment modelling of trade openness and methodology. The empirical analysis of the results is carried out in Section 4. The main findings of the current paper are outlined in Section 5, and Section 6 presents the policy recommendations.

2. Theoretical Literature

Various theories have been developed regarding the relationship between trade openness and unemployment. The Heckscher–Ohlin (HO) (Heckscher and Ohlin 1991) theory suggests that trade openness can lead to shifts in labour demand and unemployment due to changes in factor endowments and comparative advantage. The Stolper–Samuelson theorem emphasises the relationship between trade, factor prices and income distribution, indicating that trade openness can affect unemployment by altering the relative prices of labour and capital (Beker 2012; Feenstra 2018). Additionally, the New Trade Theory highlights the impact of trade openness on industry structure and labour demand, which can result in job creation or losses depending on a country’s comparative advantage (Grossman and Helpman 2018). Furthermore, the export-led growth hypothesis suggests that trade openness, particularly through exports, can promote economic growth, increase employment and lower unemployment rates (Edwards 1998). The complexities of these relationships are influenced by various factors that should be considered when examining the impact of trade openness on unemployment in the SADC region.

Empirical Literature

The empirical literature on trade openness and unemployment is inconclusive. Studies (Felbermayr et al. 2011; Gozgor 2014; Fugazza et al. 2014; Akhoondzadeh et al. 2015; Anjum and Perviz 2016; Martes 2018; Awad 2019; Nwosa et al. 2020; Bhat and Beg 2023) support trade openness as an unemployment-reducing factor. The studies documenting the negative effect of trade openness on unemployment align with the HO hypothesis that increasing trade openness in labour-abundant countries reduces unemployment. Again, the above literature posits that stimulus growth through trade boosts the demand for goods and services which raises labour’s marginal productivity and lowers unemployment.

However, Kim (2011), Nwaka et al. (2015), Nessa et al. (2021) and Nguyen (2022) argue that the increased openness to trade may increase unemployment. The studies above postulate that the positive effect of trade openness on unemployment is due to the fact that these countries are endowed with unskilled labour relative to skilled labour. Thus, trade openness helps to decrease skilled labour unemployment but leads to an increase in unskilled labour unemployment. This is also validated by Ebaidalla (2016) and Hossain et al. (2018), who assert that countries with a high degree of trade openness experience a high rate of youth unemployment. Indeed, the above studies argue that the positive effect of trade openness on unemployment results from high imports, which hurts local industries, thereby increasing unemployment. Yet, other studies (Bakhshi and Ebrahimi 2016; Mohler et al. 2018; Famode et al. 2020) advocate that trade openness is uncertain and has no effect on unemployment. In the same vein, Guneri and Erunlu (2020) and Jha (2020) argue that the net impact of trade liberalisation on unemployment is ambiguous in many settings.

The relationship between trade openness and unemployment remains a bone of contention in Africa. For example, Nwaka et al. (2015), Raifu (2017) and Onifade et al. (2019) use auto-regressive distributed lag (ARDL) and time series estimation techniques to show that trade openness worsens unemployment in Nigeria. Consistently, Asaleye et al. (2021) postulate that trade openness harms employment and wages in Nigeria’s agriculture and manufacturing sectors. The above studies ascertain that a positive effect of trade openness on unemployment could be attributed to frictional labour market conditions and the extent of the strictness of the economies’ employment protection. For example, Kim (2011) argues that trade openness raises (reduces) unemployment as the country’s employment protection is relatively stringent (laxative). Nonetheless, Nwosa et al. (2020) used ARDL and found that trade policy favours unemployment reduction in Nigeria. More so, Awad (2019) indicates that trade openness reduces youth unemployment in 50 African countries. This is consistent with Awad-Warrad’s (2018) evidence of the adverse effect of trade openness on unemployment in seven Arab countries.

Studies in SADC considered a similar measure of trade openness (a nominal measure of trade openness), yet they produced inconclusive results on the effectiveness of trade openness on unemployment. Thus, Motsatsi (2019), in their analysis of determinants of unemployment in SADC countries, considered trade openness as one of the explanatory variables. The study found a positive effect of trade openness on unemployment between 2000 and 2016. Famode et al. (2020) used the vector error correction (VEC) estimator to examine the impact of trade openness on the unemployment rate in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) for the period 1991 to 2017. Their results show that trade openness insignificantly influenced the unemployment rate. However, Khobai and Moyo (2021) assessed the effect of trade openness on industrial performance, yet their study focuses on industrial performance, which does not indicate an exact measure of unemployment. Again, the study did not consider all the SADC countries in their analysis. Their study suggests that trade openness positively affects industrial performance but is detrimental to the manufacturing sector, which has witnessed job losses and lower output levels due to a lack of competitiveness and a rise in imports.

The current research can be distinguished from previous studies by focusing on the impact of trade openness, specifically on unemployment in all (16) SADC countries. The study aims to add to the existing literature on the effectiveness of trade openness on unemployment in SADC countries. This paper considers SADC countries in one panel, which, while they may differ slightly in terms of population, land size and political systems, among other things, face similar developmental challenges, such as high unemployment rates, and share the RISDP blueprint’s goal of accelerating integration and trade openness to alleviate unemployment.

While most research utilises a nominal trade openness measure, the current paper uses a real trade openness measure which eliminates distortions due to cross-country differences in the relative price of non-tradable goods (Alcala and Ciccone 2004). This study also utilises both aggregated and disaggregated trade openness indicators. Again, real trade openness, exports and imports of goods and services are treated separately. Numerous studies have considered shorter periods (Motsatsi 2019; Khobai and Moyo 2021), used the ordinary least of square (OLS), fixed and random effect and general methods of moments (GMM) estimation techniques which only perform short-run analysis. This paper sheds light on the potential impact of trade openness on unemployment by analysing an extended period (1980–2019), a robust and efficient panel data estimation technique that allows both short and long-run analysis. Thus, the current paper utilises the panel ARDL estimate technique, preferably the pooled mean group (PMG), to examine the long-run relationship between trade openness and unemployment. The following section presents the model specification and the methodology for the current paper.

3. The Theoretical Unemployment Model

The current paper uses the panel data estimation technique to examine the effect of trade openness on unemployment in SADC countries from 1980 to 2019. In this study, panel data estimation methods are desirable as they impose homogeneity of all parameters to control unobserved heterogeneity and country-specific effects (Islam 1995). Based on the discussed literature, unemployment is a function of trade openness and other control variables. Thus, the study model is specified below:

where:

is the aggregate unemployment rate, which is the share of the labour force without work but available for and seeking employment (ILO 2021), represents real trade openness calculated as the sum of imports and exports relative to purchasing power parity GDP (Alcala and Ciccone 2004) for country at time . However, in this paper, three measures of trade openness are used: real trade openness, and the exports and imports of goods and services. The represents the control variables which include economic growth (rgdp), inflation rate (infl), foreign direct investment (fdi), government expenditure (gex), gross fixed capital formation (gcf) and human capital index(hind). is the unobserved country-specific effect and is the time trend. is the constant, and and are coefficients of the predictor variables to be estimated. is the disturbance term. The definitions and sources of the variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition and sources of variables.

The paper employs the economic growth variable based on Okun’s (1962) law proposition that economic growth is a pro-employment generation. Various studies (Raifu 2017; Motsatsi 2019; Nessa et al. 2021; Bhat and Beg 2023) document a negative effect of economic growth on unemployment. Therefore, economic growth is expected to have a reducing effect on unemployment. The inflation variable was considered based on Phillips (1958), who argued that low unemployment rates are associated with high demands for wages, thus influencing an increase in inflation. Therefore, a negative effect on inflation and employment is expected. Foreign direct investment provides recipient countries with financial stability that would ensure the formation of new firms and upgrade the existing ones, as well as enhance technology transfer and competitiveness of industries, which reinforces job creation (Ebaidalla 2016; Raifu 2017; Motsatsi 2019; Bhat and Beg 2023). In doing so, the current study expects a negative relationship between FDI and unemployment. Domestic investment also enhances the formation of new firms, creating more jobs (Ebaidalla 2016; Awad-Warrad 2018; Motsatsi 2019). Thus, gross fixed capital formation is expected to have a negative effect on unemployment.

Government expenditure captures the government’s financial resources to address unemployment issues (Nwaka et al. 2015; Raifu 2017). Therefore, government expenditure is expected to reduce the effect of unemployment. According to Anyanwu (2014) and Kpognon et al. (2020), human capital is an unemployment-reducing factor in Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, the study expects a negative effect of human capital on unemployment in SADC countries. The HO and export-led growth theories contend that trade openness reduces unemployment. Other studies (Nwaka et al. 2015; Ebaidalla 2016; Nessa et al. 2021), however, suggest that open trade’s expanding imports and the lack of skilled workforce in developing economies may have a detrimental effect on job growth. As a result, trade openness will either positively or negatively impact unemployment in SADC countries.

The current study aims to assess both the short and long-run effects of trade openness on unemployment in SADC countries. Therefore, the study employs a panel autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) estimation methodology, which is desirable since it controls endogeneity bias and assesses both long and short-run impacts of trade openness on unemployment in SADC countries (Shin et al. 1998). The estimation technique is more efficient when T > N, unlike the GMM, which biases the inferences due to instrument proliferation and unreliable autocorrelation tests when T > N (Roodman 2009).

The panel ARDL estimation techniques, which include the mean group (MG), dynamic fixed effect (DFE) and pooled mean group (MG) estimator, are consistent and efficient where T > N (Pesaran et al. 1999). Thus, with adequate lags of all variables, ARDL, particularly PMG and MG estimators, can alleviate the endogeneity problem (Shin et al. 1998). In addition, Pesaran and Smith (1995), and Pesaran et al. (1999) suggest that the mean group (MG) and the pooled mean group (PMG) allow growth regressions to have a greater degree of parameter heterogeneity than the other estimators such as the GMM and fixed effect. The PMG error correction model is presented in Equation (2):

where:

is the dependent variable (unemployment), the represents the explanatory variables and are allowed to be purely 1(0) or 1(1). is the speed of adjustment for the group of SADC countries. The is the vector of a long-run relationship. is the error correction term that represents the long-run information of the model.

Given the above panel ARDL (PMG) model in Equation (2), the unemployment model for this research in Equation (3) is now transformed into a reparameterised ARDL (p, q…. q) model. Thus, the unemployment–trade openness model is specified as follows:

where:

is the dependent variable, the represents the explanatory variables and are allowed to be purely 1(0) or 1(1). denotes the explanatory variables, including the main independent variable (trade openness) and the control variables. The is the vector of a long-run relationship. is the error correction term (ECT), which represents the long-run information of the model. The rule of thumb is that if the adjustment coefficient is positive or greater than one, it indicates model instability. However, if the adjustment coefficient is negative and less than one in absolute terms, it shows model stability. The error correction model comes with a different operator for the dependent variable. Meaning that once the ARDL is differenced, there will be a loss of lag length. Therefore, the lag length is now p − 1 and q − 1 and are short-run parameters. and denote the unit-specific fixed effects and the error term, respectively.

Under long-run slope homogeneity, the pooled estimators are consistent and efficient. As a result, the effect of heterogeneity on the means of the coefficients can be determined by the Hausman (1978) test applied to the difference between the DFE, MG and PMG. Therefore, it is also essential to test and verify the suitability and significance of the PMG estimator relative to the MG and DFE estimators based on the consistency and efficiency properties of the two estimators, using a likelihood ratio test or a Hausman (1978) test.

4. Empirical Results

To understand our data regarding the appropriate methodology for the empirical analysis, the current study described the data, carried out a unit root test and correlation tests and selected the optimal lag (see Appendix A) on all the variables.

Table 2 describes the data for the variables used in the unemployment–trade openness model. The table indicates that the average unemployment rate in SADC between 1980 and 2019 is 12.3%, and the average real trade openness is 44%. Again, Table 2 indicates that the average exports and imports are 35% and 44%, respectively. This also shows that SADC countries import more than they export between 1980 and 2019. Moreover, the descriptive statistics show that inflation has been high between 1980 and 2019 at an average of 84%. The real GDP has a mean of 3.5% between 1980 and 2019. The government expenditure ratio has a mean of around 12%, while net inflows of foreign direct investments average 3.13%, suggesting that SADC countries have been net receivers of FDI inflows between 1980 and 2019. The human capital index has a mean of 2.1. Gross fixed capital formation has a mean of 22%. The descriptive statistics indicate that the standard deviation is large enough to explore variations in the data series. In the correlation coefficient matrix (see Appendix B), there is no exact or linear relationship between the explanatory variables. Therefore, the model certainly passes the test of multicollinearity. Since the panel data are unbalanced, the paper uses the Im–Pesaran and Augmented Dickey–Fuller unit root tests (see Table 3). The stationarity tests test the null hypothesis of the unit root test and the alternative, which hypothesises that the series is stationary. The rule of thumb is to reject the null hypothesis if the p values of the Im–Pesaran and ADF are less than 0.05.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3.

Unit root test results.

The stationarity tests in Table 3 indicate that unemployment, economic growth, inflation, foreign direct investment, gross fixed capital formation, government expenditure, financial development and human capital are stationary at levels. However, trade openness and exchange rates are stationary at first difference. Since the variables under consideration have different orders of integration, the paper adopts the panel ARDL (PMG) estimation technique, which is efficient and consistent where the series of variables are not integrated in the same order (Shin et al. 1998; Ali et al. 2021). The consistency and efficiency of the panel ARDL estimates rely on several specification conditions. Thus, one of the most critical assumptions for the consistency of the ARDL model is that the regression residuals be serially uncorrelated and that the explanatory variables can be treated as exogenous (Pesaran et al. 1999).

The current research obtains an optimal lag structure for each country separately. For this purpose, the present study uses the ardl command by Kripfganz and Schneider (2018) and runs the ardl command for each country. Thus, the AIC is employed following Liew (2004), who suggests that the AIC is more efficient for smaller samples. The lag structure could not be expanded further to avoid the lack of degrees of freedom. Therefore, the most common lags for variables of interest are presented in Appendix A. Appendix A indicates that the most common lag for the variables included in the model is 1, except for foreign direct investment, which uses a lag of 0.

Regarding the empirical results, Table 4 presents the findings for the benchmark model, which evaluates the effects of real trade openness (rto) on unemployment. Table 5 and Table 6 show the results of the impact of trade openness via exports and imports. All panel ARDL estimators are presented in each measure of trade, yet the Hausman (1978) test captures the difference between homogeneity and heterogeneity. Accordingly, the p-values of the Hausman (1978) test as shown in all the estimation results tables, are greater than 0.05. Therefore, the paper’s empirical results are based on the long-run PMG estimator (short-run coefficients are available on request). The ECTs in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 are negative and significant and lower than −2 (that is, within the unit circle), which implies that there is a cointegration relationship between the variables of concern, meaning that the linkage between unemployment and the regressors is characterised by high predictability and that the spread movement is mean reverting in SADC countries.

Table 4.

Real trade openness and unemployment in SADC countries.

Table 5.

Exports of goods and services and unemployment in SADC countries.

Table 6.

Imports of goods and services and unemployment in SADC countries.

The PMG in Table 4 indicates that real trade openness has a negative effect on unemployment. Specifically, a 1% increase in trade openness would decrease the unemployment rate by 0.3% at a 1% significance level, holding other variables constant. The result is consistent with the Hecksher–Ohlin–Stolper–Samuelson theory, which advocates that an increase in a country’s openness increases the demand for labour, particularly in developing countries with abundant labour. The result aligns with Gozgor (2014), Anjum and Perviz (2016), Awad-Warrad (2018), Awad (2019), Nwosa et al. (2020) and Bhat and Beg (2023), who document evidence of the negative relationship between trade openness and unemployment. This calls for SADC governments to increase and maintain the trade openness process rather than protectionism to reduce unemployment in the region.

The empirical findings indicate that economic growth, foreign direct investment, government expenditure and gross fixed capital formation negatively and significantly affect unemployment in the long run. Thus, a 1% increase in economic growth, foreign direct investment, government expenditure and investment is associated with a 0.11%, 0.2%, 0.2% and 0.13% decrease in unemployment. Hence, a negative effect of economic growth on unemployment in both the short and long run indicates the validity of Okun’s law assertion in SADC countries. The result is consistent with Motsatsi (2019), who suggests that economic growth has a negative impact on unemployment in SADC countries.

Regarding the effect of foreign direct investment on the unemployment rate, this paper shows that FDI is indispensable to the SADC economy as increasing foreign direct investment often leads to an increased demand for workers, thus reducing the unemployment rate. The result is consistent with Habib and Sarwar (2013) and Raifu (2017), who argued that the inflow of foreign direct investment creates more employment opportunities, thus reducing unemployment.

Table 4 shows that if the government increases its consumption expenditure by one percent, the unemployment rate will fall by 0.02% in the long run. This implies that unemployment will decrease if the SADC government spends more on infrastructure, health and education. The result accords with Saraireh (2020), who documents a negative relationship between government expenditure and unemployment in Jordan.

Again, regarding investment, Table 4 indicates that increasing domestic investment creates productivity and creates more jobs, reducing unemployment in the long run. This implies that domestic investment is an unemployment reduction factor in the SADC region. Thus, domestic investment is fundamental to unemployment reduction. The result is consistent with Anyanwu (2014), Onifade et al. (2019) and Saraireh (2020), who indicated that domestic investment reduces unemployment in Africa, Nigeria and Jordan, respectively.

Inflation and human capital index (education) positively and significantly affect unemployment in SADC countries. The positive effect of inflation on unemployment shows that inflation worsens unemployment in the SADC countries. This finding refutes the theoretical assertions of the negative relationship between inflation and unemployment in the Philips curves. Hence, the results are congruent with Famode et al. (2020), who affirm that inflation harms unemployment in DRC.

The human capital variable has a positive effect on unemployment in SADC countries. The result is inconsistent with the expected a priori. This implies that unemployment still increases with a more educated population, which also suggests revisiting the education policy in SADC countries. The result is consistent with Nepram et al. (2021), who found a positive relationship between human capital and unemployment. The following table presents the results of the impact of trade openness as measured by exports on unemployment in SADC countries.

The PMG in Table 5 indicates that exports are insignificant in explaining unemployment changes in the short run in SADC countries. Yet, the export of goods and services has a negative impact on unemployment in the long run. More specifically, a 1% increase in exports of goods and services is associated with a 1.2% decrease in unemployment. This implies that the aggregate production of exports increases labour utilisation, leading to a reduction in unemployment. This result is consistent with Mashayekhi et al. (2012), who argued that increased exports and increased output lead to positive employment effects. The result also aligns with Awad-Warrad (2018), who found a negative relationship between exports and unemployment in Arab countries.

Table 6 indicates that trade openness via imports is insignificant in explaining changes in unemployment in the short run. However, a 1% increase in imports of goods and services is associated with a 0.5% increase in unemployment in the long run. This is due to the fact that the SADC imports could have increased technological advancements, which have improved the productivity of workers, thus resulting in lower employment levels as more output can be produced without the increment in the labour input. As a result, the displacement of workers by machinery (Motsatsi 2019; Khobai and Moyo 2021) could also explain the positive effect of imports on unemployment in SADC countries. The positive impact of imports on unemployment could also indicate the import dependency of many SADC economies and the impact of their resource dependency, where extractive industries essentially characterise their export sector with limited employment opportunities. The result is consistent with Awad-Warrad (2018), who found a positive relationship between imports and unemployment in Arab countries. The result is congruent with Famode et al. (2020), who suggest expanding trade openness through imports leads to the closing of local firms and increasing unemployment in DRC. This necessitates carefully identifying imports that promote higher growth and lower unemployment in SADC countries. The SADC governments should also spend more on information and technology education to equip the region’s workforce with the technical expertise to compete in the job market and create jobs for themselves.

Even if the human capital variable positively and significantly affects unemployment in SADC countries, the effect is not the same for the unemployment–exports model. Thus, Table 6 indicates a 1% increase in the human capital index leads to a 0.1% decrease in unemployment at a 1% significance level in SADC countries. This implies that increasing human capital reduces unemployment. The result aligns with Anyanwu (2014) and Kpognon et al. (2020), who suggest that human capital is an unemployment-reducing factor in Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa. This calls for effective policies that invest in the SADC citizens’ human capital, and the workforce is needed as the region imports more. Again, the unemployment–import model indicates that the variables of government expenditure and gross fixed capital formation (domestic investment) have a positive and significant effect on unemployment. More specifically, a 1% increase in government expenditure and gross fixed capital formation leads to 0.01% and 0.14% unemployment, respectively.

Table 6 shows that government consumption expenditure is positively related to unemployment. However, the result is contrary to a priori expectations. This may not be unconnected with some augments in public sector economics that the government sometimes does engage in unproductive investment or spending. The result aligns with Nwosa (2014) and Raifu (2017), who argued that government expenditure increases unemployment in Nigeria.

According to the import–unemployment model, gross fixed capital formation positively and significantly affects unemployment. The result is inconsistent with the expected a priori of this paper. This could be explained by the fact that while labour-abundant SADC countries import more, most investments become digital ones that only employ a few people familiar with digitalisation and technologies. This creates inequalities in the labour market that cause unskilled labour to be unemployed. The result aligns with Nasution et al. (2021) who argue that rapid technological developments will eventually replace human work, making unemployment endless. To prove the reliability of our results, this study performed diagnostic and stability tests.

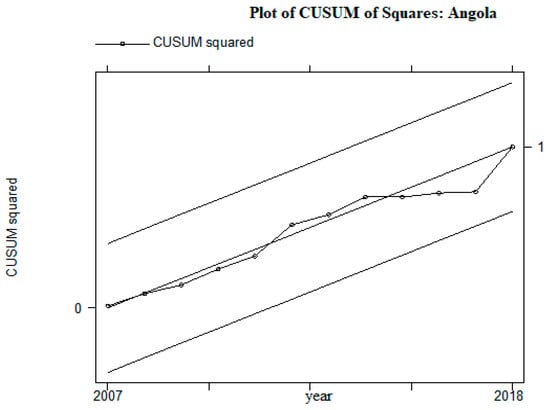

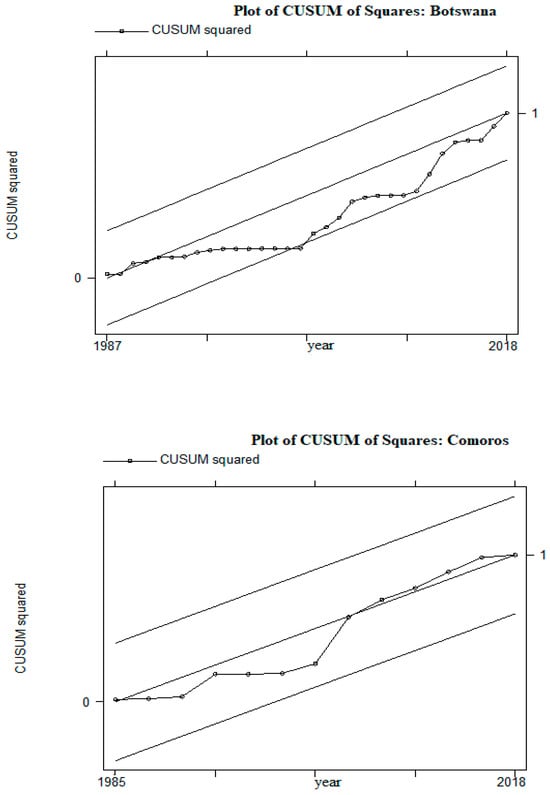

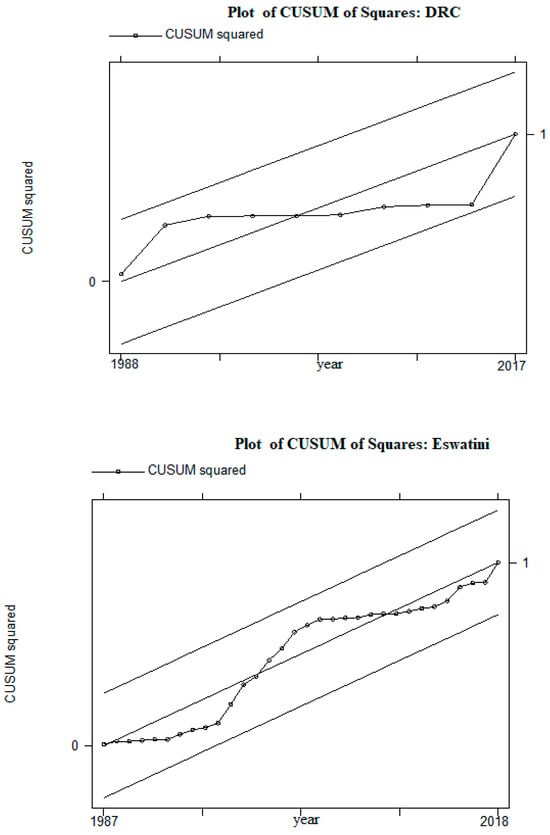

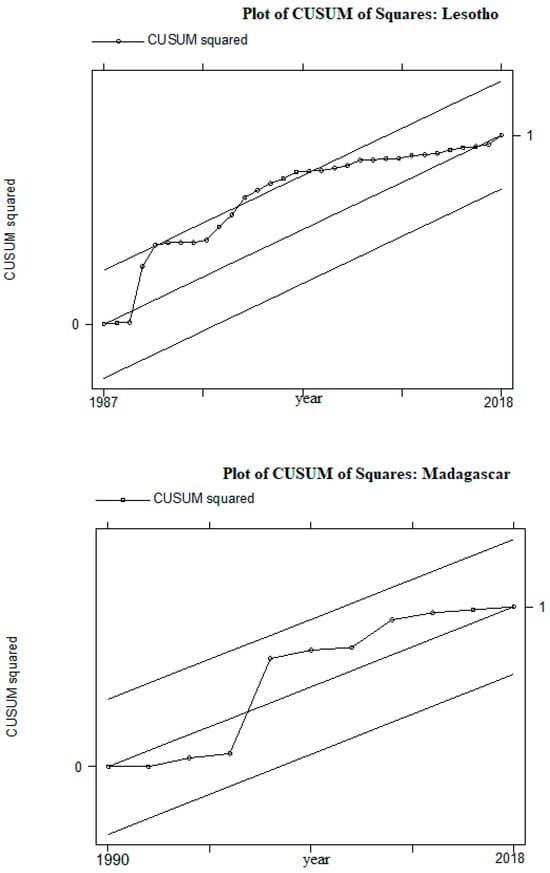

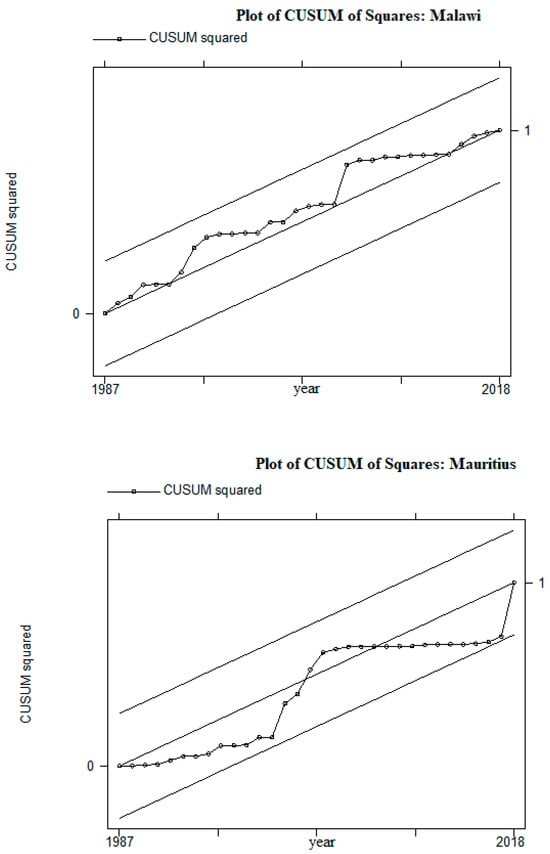

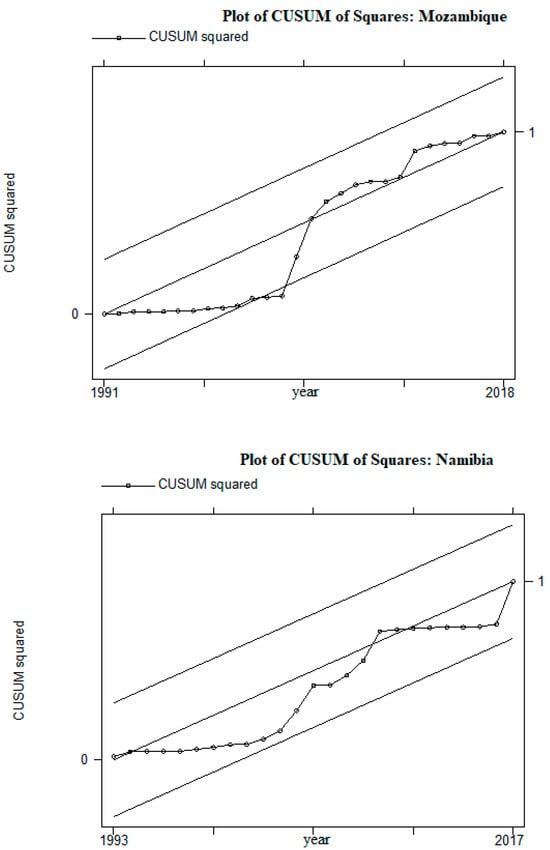

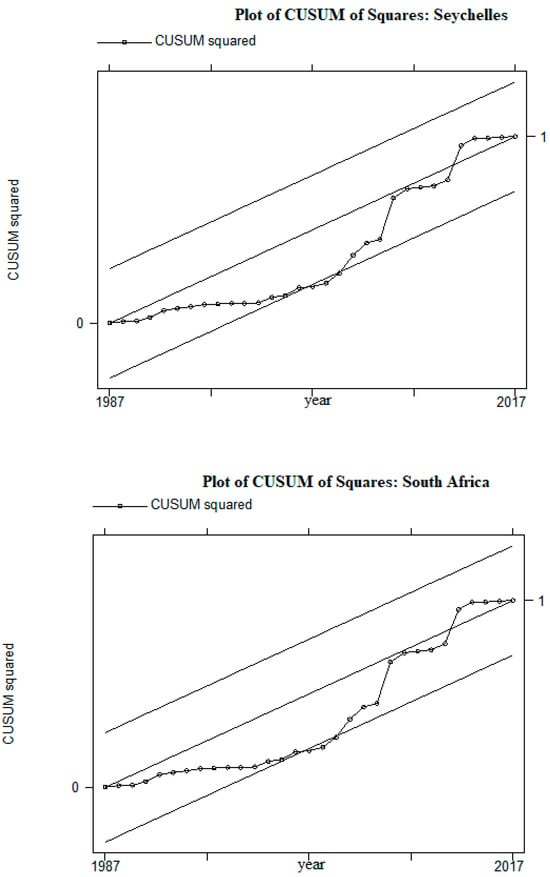

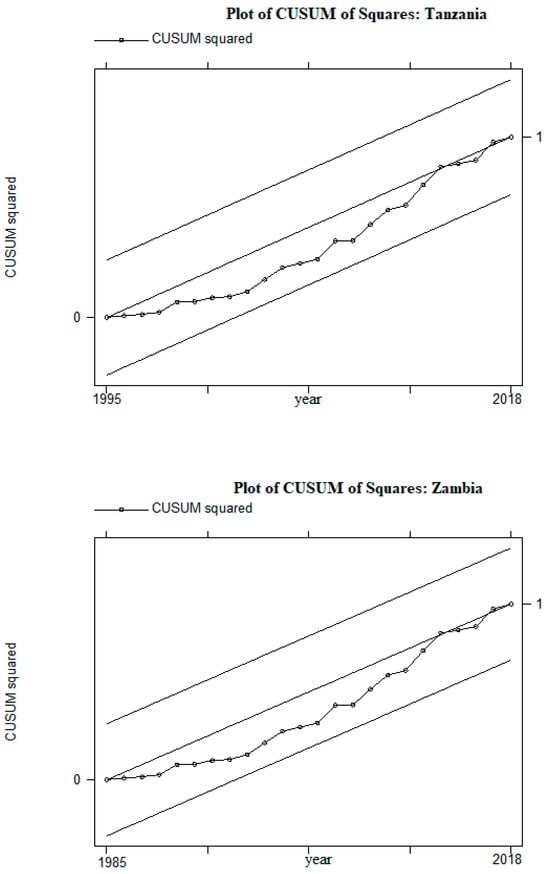

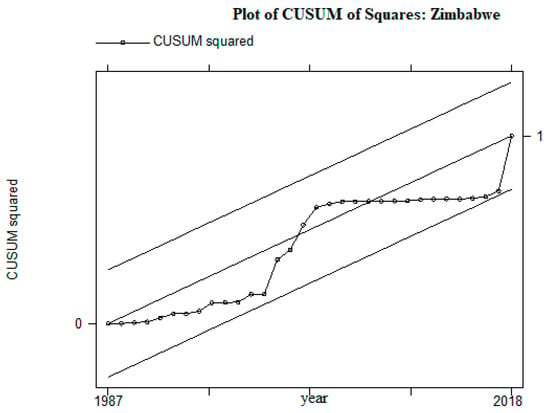

Various diagnostic checks were conducted to ensure that classical regression assumptions were not violated. According to the results of diagnostic tests given in Appendix C, the assumptions of no heteroscedasticity, normality of residuals, specification of the functional form of the model and no autocorrelation were confirmed. According to Bahmani-Oskooee and Nasir (2004), if the plot of the CUSUMQ (see Appendix D) sample path moves outside the critical region, and in this case, at a 5% significance level, the null hypothesis of stability over time of the intercept and slope parameters is rejected, meaning that the economic growth models for SADC countries are stable.

5. Summary and Conclusions

This study employed the PMG estimation technique to examine the impact of trade openness on unemployment in SADC countries from 1980 to 2019. Diagnostic tests were conducted to validate classical regression assumptions, including the Durbin–Watson and B-Godfrey autocorrelation test, the White heteroscedasticity test, and CUSUMQ to assess model stability. The Hausman test was used to determine the appropriate estimator, with the PMG estimator being selected due to its p-value exceeding 0.05%.

In the short run, the PMG results revealed an insignificant relationship between trade openness and unemployment in SADC. However, economic growth and government expenditure impacted unemployment negatively and significantly in the short run. In the long run, the study identified that real trade openness and exports of goods and services reduced unemployment in SADC countries. Therefore, it is crucial to continue the process of trade openness, mainly through trade and exportation, rather than resorting to protectionism, to reduce the region’s unemployment rates effectively. However, the study also revealed that trade openness through imports exacerbated unemployment in SADC countries. This highlights the need for caution in international trade policies, particularly regarding importation, when formulating strategies to address unemployment.

Furthermore, the findings of this study support Okun’s law, indicating that economic growth plays a role in reducing unemployment in SADC countries. Additionally, foreign direct investment, government expenditure and gross fixed capital formation were identified as factors that reduce unemployment in SADC countries. However, the impact of the human capital index on unemployment differed between the models of unemployment–real trade openness and openness–export. Furthermore, the study found a positive relationship between government expenditure, gross fixed capital formation and unemployment in the unemployment–imports model. Lastly, the study’s results indicated that the long-run Philips curve hypothesis could not be confirmed in the SADC region.

These findings underscore the importance of sustained economic growth, prudent trade policies and targeted investments in education and technology to address unemployment challenges in SADC countries.

6. Policy Implications

The findings of this study, which assesses the impact of trade openness on unemployment in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) from 1980 to 2019 using panel ARDL estimation techniques, hold important implications for theory, practice and policy.

Theoretically, the negative relationship between trade openness and unemployment and the negative impact of exports on unemployment aligns with theories such as the Heckscher–Ohlin theory and the export-led growth hypothesis. These findings support the notion that increasing real trade openness and promoting export-oriented industries can reduce unemployment rates in the long run.

Regarding practical implications, the results suggest that SADC countries should prioritise policies that enhance trade openness and encourage export-oriented activities. By creating an enabling environment for trade, such as reducing trade barriers and promoting trade agreements, governments can stimulate economic growth and job creation. The study’s findings also highlight the importance of diversifying exports and enhancing competitiveness to maximise the positive impact on employment.

On the policy front, the positive relationship between imports and unemployment indicates the need for policies that mitigate the potential job losses associated with imports. Governments should carefully manage and monitor imports to prevent harm to domestic industries and employment. Policymakers may implement targeted industrial policies, trade adjustment assistance programs or training initiatives to facilitate the transition of workers from declining sectors to those experiencing growth.

Overall, the study’s results emphasise the importance of a balanced and nuanced approach to trade policies in the SADC region. While promoting trade openness and export-oriented strategies can help reduce unemployment, policymakers must also address the potential negative consequences of imports on domestic employment. By implementing evidence-based policies considering these dynamics, governments can effectively foster sustainable economic development and tackle unemployment challenges in SADC countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G., K.S. and P.N.; methodology, D.G.; software, D.G., K.S., P.N.; validation, D.G., P.N. and K.S.; formal analysis, D.G.; investigation, K.S. and P.N.; resources, K.S.; data curation, D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G.; writing—review and editing, K.S. and P.N.; visualization, D.G. and P.N.; supervision, K.S.; project administration, D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Lag length selection.

Table A1.

Lag length selection.

| Variables | unem | rto | exp | imp | rgdp | infl | fdi | gex | gcf | hind |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | ||||||||||

| Angola | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Botswana | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Comoros | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Eswatini | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lesotho | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Madagascar | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Malawi | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mauritius | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Mozambique | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Namibia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| South Africa | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Seychelles | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tanzania | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Zambia | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Zimbabwe | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Common lag | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Source: Author’s compilation from Stata ARDL AIC lag length selection criterion.

Appendix B

Table A2.

Correlation matrix.

Table A2.

Correlation matrix.

| lunem | lrto | lexp | limp | lrgdp | linfl | lfdi | lgex | lgcf | lhind | |

| lunem | 1.000 | |||||||||

| lrto | 0.176 * | 1.000 | ||||||||

| lexp | 0.346 ** | 0.645 * | 1.000 | |||||||

| limp | 0.141 * | 0.656 ** | 0.668 * | 1.000 | ||||||

| lrgdp | −0.014 * | 0.082 * | 0.039 * | 0.081 * | 1.000 | |||||

| linfl | 0.143 * | −0.171 * | −0.002 * | −0.102 * | 0.047 * | 1.000 | ||||

| lfdi | −0.203 * | 0.101 * | 0.233 * | 0.335 | 0.212 | 0.068 * | 1.000 | |||

| lgex | 0.103 * | −0.095 * | 0.028 * | −0.098 * | 0.016 * | 0.010 * | −0.104 * | 1.000 | ||

| lgcf | −0.055 * | 0.145 ** | 0.167 * | 0.306 * | 0.426 * | 0.071 * | 0.373 * | −0.078 * | 1.000 | |

| lhind | −0.103 * | 0.245 * | 0.105 * | 0.267 * | −0.106 * | −0.291 * | 0.051 | −0.028 * | 0.069 * | 1.000 |

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1; Source: Author’s compilation from Stata correlation regression.

Appendix C

Table A3.

Diagnostic test results.

Table A3.

Diagnostic test results.

| Group/Country | Durbin–Watson | B-Godfrey Test Statistic | White Test Statistic | CUSUM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Angola | 2.893 | 9.623 | 16.000 | stable |

| 2. Botswana | 1.365 | 3.319 | 18.000 | stable |

| 3. Comoros | 2.011 | 0.167 | 18.000 | stable |

| 4. Democratic Republic of Congo | 3.098 | 8.718 | 17.000 | stable |

| 5. Eswatini | 3.456 | 5.736 | 18.000 | stable |

| 6. Lesotho | 2.023 | 0.067 | 19.000 | stable |

| 7. Madagascar | 2.126 | 0.591 | 18.000 | stable |

| 8. Malawi | 3.280 | 15.130 | 18.000 | stable |

| 9. Mauritius | 2.451 | 10.040 | 18.000 | stable |

| 10. Mozambique | 2.722 | 5.155 | 18.000 | stable |

| 11. Namibia | 3.099 | 7.571 | 17.000 | stable |

| 12. Seychelles | 2.536 | 1.880 | 24.000 | stable |

| 13. South Africa | 2.574 | 6.148 | 17.000 | stable |

| 14. Tanzania | 1.335 | 1.065 | 18.000 | stable |

| 15. Zambia | 2.099 | 0.879 | 19.000 | stable |

| 16. Zimbabwe | 2.001 | 0.509 | 19.000 | stable |

Standard errors in parentheses; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1; Source: Author’s compilation from STATA ARDL diagnostic test results.

Appendix D

Figure A1.

Plot of the cumulative sum of squares (CUSUMQ) of recursive residuals. Source: extract results from STATA ARDL diagnostic tests.

Box A1. SADC countries.

Angola, Botswana, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Eswatini, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe

References

- Akhoondzadeh, Tahereh, Farshid Salimi, and Mohamad Reza Arsalanbod. 2015. Openness of Trade, Unemployment and Inequality of Income Distribution: Comparison between Developed and Developing Countries. International Economics Studies 45: 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Alcala, Franncisco, and Antonio Ciccone. 2004. Trade and Productivity. The Quartely Journal of Economics 119: 613–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Sajid, Zulkornain Yusop, Shivee Ranjanee Kaliappan, Lee Chin, and Muhammad Saeed Meo. 2021. Impact of Trade Openness, Human Capital, Public Expenditure and Institutional Performance on Unemployment: Evidence from OIC Countries. International Journal of Manpower 43: 1108–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, Nazia, and Zahid Perviz. 2016. Effect of Trade Openness on Unemployment in Case of Labour and Capital Abundant Countries. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 5: 44–58. Available online: https://bbejournal.com/index.php/BBE/article/view/248 (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Anyanwu, John C. 2014. Does Intra-African Trade Reduce Youth Unemployment in Africa? African Development Review 26: 286–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaleye, Abiola John, Joseph Olufemi Ogunjobi, and Omotola Adedoyin Ezenwoke. 2021. Trade Openness Channels and Labour Market Performance: Evidence from Nigeria. International Journal of Social Economics 48: 1589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, Atif. 2019. Economic Globalisation and Youth Unemployment—Evidence from African Countries. International Economic Journal 33: 252–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad-Warrad, Taleb. 2018. Trade Openness, Economic Growth and Unemployment Reduction in Arab Region. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 8: 179–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, and A. B. M. Nasir. 2004. ARDL Approach to Test the Productivity Bias Hypothesis. Review of Development Economics 8: 483–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, Zahra, and Mehrzad Ebrahimi. 2016. The Effect of Real Exchange Rate on Unemployment. Marketing and Branding Research 3: 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, Robert Joseph, and Xavier Sala-i-Martin. 1997. Technological Diffusion, Convergence, and Growth. Journal of Economic Growth 2: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beker, Victor A. 2012. A Case Study on Trade Liberalization: Argentina in the 1990s. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Belenkiy, Maksim, and David Riker. 2015. Theory and Evidence Linking International Trade to Unemployment Rates. 2015-01B; Washington, DC: United States of America. Available online: https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/ec201501b.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Belmonte, Zachariah John, Charles Bandola, Rexmelle Decapia, and Eugene Chris Gonzaga. 2021. Do Technological Developments Reduce Unemployment in the Philippines? Paper presented at ITMS 2021—2021 62nd International Scientific Conference on Information Technology and Management Science of Riga Technical University, Riga, Latvia, October 14–15; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, Mudaser Ahad, and Mirza Nazrana Beg. 2023. Revisiting the Trade Openness–Unemployment Nexus: An Application of the Novel JKS Panel Causality Test with Static and Dynamic Panel Models. Journal of Economic Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Donald R. 1998. Does European Unemployment Prop Up American Wages? National Labor Markets and Global Trade. American Economic Review 88: 478–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ebaidalla, Ebaidalla Mahjoub. 2016. Determinants of Youth Unemployment in OIC Member States: A Dynamic Panel Data Analysis. Journal of Economic Cooperation and Development 37: 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Sebastian. 1998. Openness, Productivity, and Growth: What Do We Really Know? The Economic Journal 108: 383–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, Hartmut, and Udo Kreickemeier. 2008. International Fragmentation: Boon or Bane for Domestic Employment? European Economic Review 52: 116–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Famode, David Masamba, Patrick Matata Makalamba, and K. N. Ngobula. 2020. Econometric Assessment of Relationship Between Trade Openness and Unemployment in Africa: The Case Study of Democratic Republic of Congo. International Journal of Economics and Buisness Adminstration 6: 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Feenstra, Robert C. 2018. Alternative Sources of the Gains from International Trade: Variety, Creative Destruction, and Markups. Journal of Economic Perspectives 32: 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felbermayr, Gabriel, Julien Prat, and Hans Jörg Schmerer. 2011. Trade and Unemployment: What Do the Data Say? European Economic Review 55: 741–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugazza, Marco, Celine Carrere, Marcelo Olarreaga, and Fredric Robert-Nicoud. 2014. Trade in Unemployment. New York and Geneva: United Nations, No. 64. ISSN 1607-8291. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/itcdtab64_en.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Gozgor, Giray. 2014. The Impact of Trade Openness on the Unemployment Rate in G7 Countries. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development 23: 1018–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, Gene M., and Elhanan Helpman. 2018. Growth, Trade, and Inequality. Econometrica 86: 37–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guneri, Barb, and Zeynep Erunlu. 2020. The Effects of Trade Liberalization and Export Diversification on Unemployment: An Empirical Analysis. Journal of Faculty of Economics and Adminstrative Sciences 10: 617–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, Malik Danish, and Saima Sarwar. 2013. Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Employment Level In Pakistan: A Time Series Analysis. Journal of Law, Policy and Globalisation 10: 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hausman, Jerry A. 1978. Specification Tests in Econometrics. Econometrica 46: 1251–71. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1913827%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org/%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=econosoc.%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org (accessed on 8 August 2017). [CrossRef]

- Heckscher, Eli Filip, and Bertil Gotthard Ohlin. 1991. Heckscher-Ohlin Trade Theory. Translated, Edited and Introduce by Harry Flam and M. Flanders. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helpman, Elhanan, and Oleg Itskhoki. 2010. Labour Market Rigidities, Trade and Unemployment. Review of Economic Studies 77: 1100–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Mohammad Iqbal, Farian Tahrim, Md Sabbir Hossain, and Md Maznur Rahman. 2018. Relationship between Trade Openness and Unemployment: Empirical Evidence for Bangladesh. Indian Journal of Economics and Development 6: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Organisation (ILO). 2020. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2020. Geneva: ILO. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Organisation (ILO). 2021. Unemployment Total (% of Total Labour Force) Modeled ILO Estimates. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Islam, Nazrul. 1995. Growth Empirics: A Panel Data Approach. The Quartely Journal of Economics 110: 1127–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, Priyaranjan. 2020. International Trade and Unemployment. Contributions to Economics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khobai, Hlalefang, and Clement Moyo. 2021. Trade Openness and Industry Performance in SADC Countries: Is the Manufacturing Sector Different? International Economics and Economic Policy 18: 105–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jaewon. 2011. The Effects of Trade on Unemployment: Evidence from 20 OECD Countries. Research Papers in Economics 19: 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Young Joon, Kyungsoo Kim, and Su Kyoung Lee. 2017. The Rise of Technological Unemployment and Its Implications on the Future Macroeconomic Landscape. Futures 87: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kpognon, Koffi, Henri Atangana Ondoa, and Mamadou Bah. 2020. Trade Openness and Youth Employment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Should We Regulate the Labor Market? Journal of Economic Integration 35: 751–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripfganz, Sebastian, and Daniel C. Schneider. 2018. ARDL: Estimating Autoregressive Distributed Lag and Equilibrium Correction Models. Paper presented at London Stata Conference, London, UK, September 6–7; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liew, Venus Khim-sen. 2004. Which Lag Length Selection Criteria Should We Employ. Economics Bulletin 3: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, Tahir, Amjid Ali, Noureen Akhtar, Muhammad Iqbal, Sadia Qamar, Hafiz Zafar Nazir, Nasir Abba, and Iram Sana. 2014. Determinants of Unemployment in Pakistan: A Statistical Study. International Journal of Asian Social Science 4: 1163–75. [Google Scholar]

- Martes, E. 2018. The Effect of Trade Openness on Unemployment: Long-Run Versus Short-Run. Bachelor’s thesis, Erasmus School of Economics, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Available online: https://thesis.eur.nl/pub/43403/ (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Mashayekhi, Mina, Ralf Peters, and David Vanzetti. 2012. Regional Integration and Employment Effects in SADC. In Policy Priorities for International Trade and Jobs. Paris: OECD, pp. 387–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohler, Lukas, Rolf Weder, and Simone Wyss. 2018. International Trade and Unemployment: Towards an Investigation of the Swiss Case. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics 154: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Motsatsi, Johane Moilwa. 2019. Unemployment in the SADC Region. 64. In The Global Diamond Industry: Economics and Development. Gabrone: Palgrave Macmillan Limited. ISBN 99912-65-71-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msigwa, Robert, and Erasmus Fabian Kipesha. 2013. Determinants of Youth Unemployment in Developing Countries: Evidences from Tanzania. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development 4: 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nasution, Bahrul Ilmi, Adelia Christine Br. Tarigan, and Sri Indriyani Siregar. 2021. Investment and Unemployment Reduction: An Empirical Study of Indonesia Using Panel Data Regression. Science and Technology Publications 2020: 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepram, Damodar, Salam Prakash Singh, and Samsur Jaman. 2021. The Effect of Government Expenditure on Unemployment in India: A State Level Analysis. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 8: 763–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nessa, Hazera Tun, Md Alauddin, and Rezwanul Huque Khan. 2021. Effects of Trade Opennesss on Unemployment Rate: Evidence from Selected Least Developed Countries (LDCS). Journal of Buisness Administration 42: 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Anh Tru. 2022. The Relationship Between Economic Growth, Foreign Direct Investment, Trade Openness, and Unemployment in South Asia. Asian Academy of Management Journal 27: 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nwaka, Ikechukwu D., Kalu E. Uma, and Gulcay Tuna. 2015. Trade Openness and Unemployment: Empirical Evidence for Nigeria. Economic and Labour Relations Review 26: 117–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwosa, Philip, Sunday Keji, Samuel Adegboyo, and Oluwadamilola Fasina. 2020. Trade Openness and Unemployment Rate in Nigeria. Oradea Journal of Buisness and Economics 5: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwosa, Philip Ifeakachukwu. 2014. Government Expenditure, Unemployment and Poverty Rates in Nigeria. Journal of Research in National Development 12: 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Okun, Arthur M. 1962. Potential GNP: Its Measurement and Significance. Paper presented at Business and Economic Statistics Section of the American Statistical Association, Minneapolis, MN, USA, September 7–10; pp. 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Onifade, Stephen Taiwo, Ahmet Ay, Simplice Asongu, and Festus Victor Bekun. 2019. Revisiting the Trade and Unemployment Nexus: Empirical Evidence from the Nigerian Economy. Journal of Public Affairs 20: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. Hashem, and Ron Smith. 1995. Estimating Long-Run Relationships from Dynamic Heterogeneous Panels. Journal of Econometrics 68: 79–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. Hashem, Yongcheol Shin, and Ron. P Smith. 1999. Pooled Mean Group Estimation of Dynamic Heterogenous Panels. Journal of the American Statistical Association 94: 621–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Alban William. 1958. The Relation Between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957. Economica 25: 283–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raifu, Akande Isiaka. 2017. On the Determinants of Unemployment in Nigeria: What Are the Roles of Trade Openness and Current Account Balance? Review of Innovation and Competitiveness 3: 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, David. 1817. Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Roodman, David. 2009. How to Do Xtabond2: An Introduction to Difference and System GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal 9: 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraireh, Shadi. 2020. The Impact of Government Expenditures on Unemployment: A Case Study of Jordan. Asian Journal of Economic Modelling 8: 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Peter. 2002. The Direct and Indirect Effects of Unemployment on Poverty and Inequality. SPRC Discussion Paper 118: 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Yongcheol, M. Hashem Pesaran, and Ron P. Smith. 1998. Discussion Paper Series Number 16 Pooled Mean Group Estimation of Dynamic Heterogeneous Panels. Economics 44: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Southern African Development Community (SADC). 2014. Annual Report: 2013–2014. Gaborone Botswana. Available online: www.sadc.int (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- Southern African Development Community (SADC) Secretariat. 2003. Annual Report: 2002–2003. Gaborone Botswana. Available online: www.sadc.int (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Southern African Development Community (SADC) Secretariat. 2020. Annual Report 2019–2020. Gaborone Botswana. Available online: www.sadc.int (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Spohr, Alexandre Piffero, and André Luiz Reis da Silva. 2017. Foreign Policy’s Role in Promoting Development: The Brazilian and Turkish Cases. Contexto Internacional 39: 157–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, Kapsos, and Bourmpoula Evangelina. 2013. Employment and Economic Class in the Developing World. ILO Research Paper No. 6. Geneva: ILO, vol. 53, p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2020a. The African Continental Free Trade Area: Economic and Distributional Effects. In Advances in African Economic, Social and Political Development. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2020b. World Bank, World Development Indicators. 2020. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS (accessed on 17 November 2021).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).