Energy Conservation with Open Source Ad Blockers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

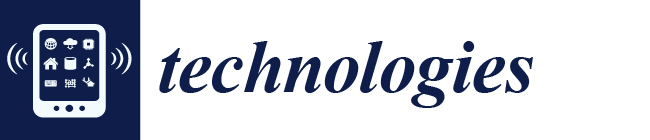

2.1. Ad Blocker Selection

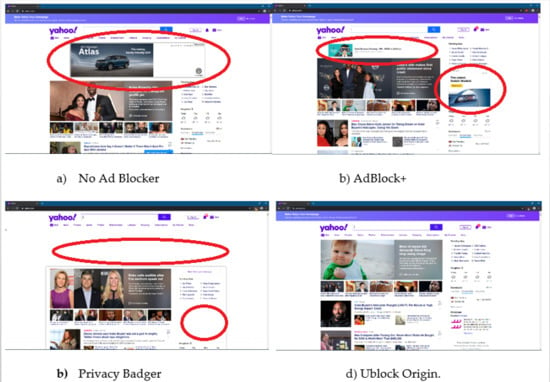

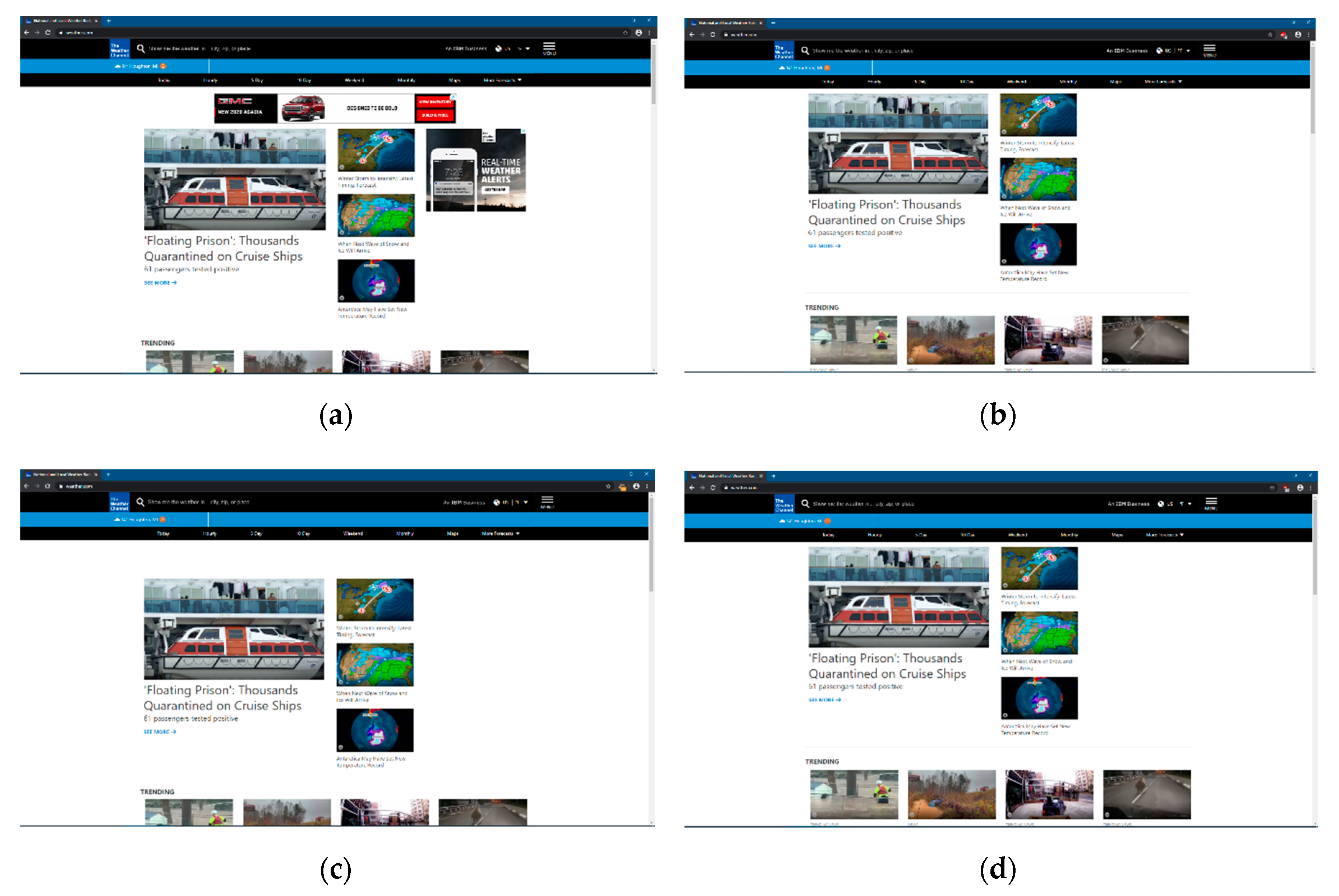

2.2. Ad Blocker Testing on Webpages

2.3. Ad Blocker Testing of Streaming Video

2.4. Energy Conservation Estimates

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cole, J.I.; Suman, M.; Schramm, P.; Zhou, L. Surveying the Digital Future. 2017. Available online: http://www.digitalcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/2017-Digital-Future-Report.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2020).

- Aslan, J.; Mayers, K.; Koomey, J.G.; France, C. Electricity Intensity of Internet Data Transmission: Untangling the Estimates. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 22, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, P.; Buonocore, J.; Eckerle, K.; Hendryx, M.; Stout, B.; Heinberg, R.; Clapp, R.; May, B.; Reinhart, N.; Ahern, M.; et al. Full cost accounting for the life cycle of coal. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1219, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prehoda, E.W.; Pearce, J.M. Potential lives saved by replacing coal with solar photovoltaic electricity production in the U.S. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heddeghem, W.; Lambert, S.; Lannoo, B.; Colle, D.; Pickavet, M.; Demeester, P. Trends in worldwide ICT electricity consumption from 2007 to 2012. Comput. Commun. 2014, 50, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deighton, J.; Kornfeld, L.; Gerra, M. Economic Value of the Advertising-Supported Internet Ecosystem. 2017. Available online: https://www.iab.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Economic-Value-Study-2017-FINAL2.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2020).

- Li, W.; Huang, Z. The Research of Influence Factors of Online Behavioral Advertising Avoidance. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2016, 6, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E.; Swinyard, W.R. Information Response Models: An Integrated Approach. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; King, T. Don’t negate the whole field. Mark. Res. 2003, 15, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Pasadeos, Y. Perceived Informativeness of and Irritation with Local Advertising. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2016, 67, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, S.; Wang, Y.; Ruth, R.; Frank, A. The Web Motivation Inventory: Replication, Extension, and Application to Internet Advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2007, 26, 447–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.B.; Zahay, D.L.; Thorbjørnsen, H.; Shavitt, S. Getting too personal: Reactance to highly personalized email solicitations. Mark. Lett. 2008, 19, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.L.; Zahay, D. Internet Marketing: Integrating Online and Offline Strategies; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-285-40203-1. [Google Scholar]

- Milne, G.R.; Boza, M.-E. Trust and Concern in Consumers’ Perceptions of Marketing Information Management Practices. J. Interact. Mark. 1999, 13, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, G.J.; Joseph, P. Understanding Privacy Concerns: An Assessment of Consumers’ Information-Related Knowledge and Belief. J. Direct Mark. 1992, 6, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurau, C.; Ashok, R.; Claire, G. To Legislate or Not to Legislate: A Comparative Study of Privacy/Personalization Factors Affecting French, UK and US Web Sites. J. Consum. Mark. 2003, 20, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, F. The 14 Best Mozilla Firefox Add-ons, Apps & Extensions of 2020. Product. Land 2019. Available online: https://productivityland.com/best-firefox-add-ons-extensions/ (accessed on 23 February 2020).

- Spadafora, A. These are the most popular Google Chrome extensions. Tech. Radar 2019. Available online: https://www.techradar.com/news/most-popular-google-chrome-extensions (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- Evans, D.S. The Online Advertising Industry: Economics, Evolution, and Privacy. J. Econ. Perspect. 2009, 23, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, T. For Online Privacy, Click Here. The New York Time. 19 January 2012. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/20/business/media/the-push-for-online-privacy-advertising.html (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Lipman, R. Online Privacy and the Invisible Market for Our Data. Penn St. L. Rev. 2015, 120, 777. [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne-Castro, J. Digital Advertising and Consumer Privacy: Three Trends to Watch. Mar. Tech. Advis. 2018. Available online: https://www.martechadvisor.com/articles/ads/digital-advertising-and-consumer-privacy-three-trends-to-watch/ (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- Hansen, M.; Köhntopp, K.; Pfitzmann, A. The Open Source approach—opportunities and limitations with respect to security and privacy. Comput. Secur. 2002, 21, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, J.; Fitzgerald, B. Understanding Open Source Software Development; Addison-Wesley: London, UK, 2002; pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani, K.R.; Wolf, R.G. Why hackers do what they do: Understanding motivation and effort in free/open source software projects. Perspect. Free Open Source Softw. 2005, 1, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippel, E.V.; Krogh, G.V. Open source software and the “private-collective” innovation model: Issues for organization science. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M. Building Research Equipment with Free, Open-Source Hardware. Science 2012, 337, 1303–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J. Open-Source Lab: How to Build Your Own Hardware and Reduce Research Costs, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb, A.; Abadie, S. Building Open Source Hardware: DIY Manufacturing for Hackers and Makers, 1st ed.; Addison-Wesley Professional: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Oberloier, S.; Pearce, J.M. General Design Procedure for Free and Open-Source Hardware for Scientific Equipment. Designs 2018, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Source AdBlock Alternatives-AlternativeTo.net. Available online: https://alternativeto.net/software/adblock-for-chrome/?license=opensource (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- Allowing Acceptable Ads in Adblock Plus. Available online: https://adblockplus.org/en/acceptable-ads (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- 10 Ad Blocking Extensions Tested for Best Performance • Raymond.CC. Available online: https://www.raymond.cc/blog/10-ad-blocking-extensions-tested-for-best-performance/ (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Haile, T. What You Think You Know About the Web Is Wrong. Time. 2014. Available online: https://time.com/12933/what-you-think-you-know-about-the-web-is-wrong/ (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Kemp, S. Digital trends 2019: Every Single Stat You Need to Know about the Internet. Available online: https://thenextweb.com/contributors/2019/01/30/digital-trends-2019-every-single-stat-you-need-to-know-about-the-internet/ (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Desroches, L.-B.; Fuchs, H.; Greenblatt, J.; Pratt, S.; Willem, H.; Claybaugh, E.; Beraki, B.; Nagaraju, M.; Price, S.; Young, S. Computer Usage and National Energy Consumption: Results from a Field-Metering Study; Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. (LBNL): Berkeley, CA, USA, 2014.

- United States Internet Usage and Population State by State. Available online: https://www.internetworldstats.com/unitedstates.htm (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- EIA-Electricity Data. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/electricity/monthly/epm_table_grapher.php?t=epmt_5_6_a (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Electricity Prices around the World | GlobalPetrolPrices.com. Available online: https://www.globalpetrolprices.com/electricity_prices/ (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Alexa-Top Sites. Available online: https://www.alexa.com/topsites (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- YouTube. Press–YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/about/press/ (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Nielo, D. All the Ways Google Tracks You—And How to Stop It. Wired. 27 May 2019. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/google-tracks-you-privacy/ (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Caiazzo, F.; Ashok, A.; Waitz, I.A.; Yim, S.H.L.; Barrett, S.R.H. Air pollution and early deaths in the United States. Part I: Quantifying the impact of major sectors in 2005. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 79, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedoussi, I.C.; Barrett, S.R.H. Air pollution and early deaths in the United States. Part II: Attribution of PM2.5 exposure to emissions species, time, location and sector. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 99, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burney, J.A. The downstream air pollution impacts of the transition from coal to natural gas in the United States. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, M. Massacre sparks foreign criticism of U.S. gun culture. Reuters. 17 April 2007. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-crime-shooting-world/massacre-sparks-foreign-criticism-of-u-s-gun-culture-idUSL1752333820070417 (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Pearce, J.M. Towards Quantifiable Metrics Warranting Industry-Wide Corporate Death Penalties. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizli, V.; Marx Gómez, J. A Framework to Optimize Energy Efficiency in Data Centers Based on Certified KPIs. Technologies 2018, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Bai, X. A review of air conditioning energy performance in data centers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, K.; Galante, R.M.; Ohadi, M.M. Energy consumption analysis of a medium-size primary data center in an academic campus. Energy Build. 2014, 76, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Mochizuki, M.; Mashiko, K.; Nguyen, T. Heat pipe based cold energy storage systems for datacenter energy conservation. Energy 2011, 36, 2802–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Gu, L.; Qi, X. Comparative Study of Energy Performance between Chip and Inlet Temperature-Aware Workload Allocation in Air-Cooled Data Center. Energies 2018, 11, 669. [Google Scholar]

- Priyadumkol, J.; Kittichaikarn, C. Application of the combined air-conditioning systems for energy conservation in data center. Energy Build. 2014, 68, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.; Luo, Z.; Gong, H.; Gan, T. Optimization of the thermal environment of a small-scale data center in China. Energy 2020, 196, 117080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.B.; York, R. Reducing the web’s carbon footprint: Does improved electrical efficiency reduce webserver electricity use? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 65, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, H.; Liu, R.; Wang, M.; Li, C. Configuration Optimization Model for Data-Center-Park-Integrated Energy Systems under Economic, Reliability, and Environmental Considerations. Energies 2020, 13, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cerero, D.; Fernández-Montes, A.; Velasco, F. Productive Efficiency of Energy-Aware Data Centers. Energies 2018, 11, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahari, H.I.; Shariff, S.S.M. Review on data center issues and challenges: Towards the Green Data Center. In Proceedings of the 2016 6th IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering (ICCSCE), Penang, Malaysia, 25–27 November 2016; pp. 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, S.; Chaudhry, S.A.; Kiran, S. Adaptive TrimTree: Green Data Center Networks through Resource Consolidation, Selective Connectedness and Energy Proportional Computing. Energies 2016, 9, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Building Efficient Data Centers with the Open Compute Project | Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/notes/facebook-engineering/building-efficient-data-centers-with-the-open-compute-project/10150144039563920/ (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Oberloier, S.; Pearce, J.M. Open source low-cost power monitoring system. HardwareX 2018, 4, e00044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhar, F.; Javed, B.; ur Rasool, R.; Malik, O.; Zulfiqar, K. Software level green computing for large scale systems. J. Cloud Comput. 2012, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byard, D.J.; Woern, A.L.; Oakley, R.B.; Fiedler, M.J.; Snabes, S.L.; Pearce, J.M. Green fab lab applications of large-area waste polymer-based additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 27, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stifter, M.; Widl, E.; Andrén, F.; Elsheikh, A.; Strasser, T.; Palensky, P. Co-simulation of components, controls and power systems based on open source software. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Power Energy Society General Meeting, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–25 July 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, R.S.; Lee, G.E.; Johnson, P.M. The Kukui Cup: A Dorm Energy Competition Focused on Sustainable Behavior Change and Energy Literacy. In Proceedings of the 2011 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Koloa, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, P.; Pearce, J.M.; Harrap, R.; Daniel, S. The application of smartphone technology to economic and environmental analysis of building energy conservation strategies. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2012, 31, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenika, I.; Pearce, J.M. The Internet and other ICTs as tools and catalysts for sustainable development: Innovation for 21st century. Inf. Dev. 2013, 29, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.-J.; Bonnell, J.; Agogino, A.M. Energy Conservation Utilizing Wireless Dimmable Lighting Control in a Shared-Space Office. In Proceedings of the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America Annual Conference 2008, Savannah, GA, USA, 10–11 November 2008; pp. 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Capehart, B.L.; Middelkoop, T. Handbook of Web Based Energy Information and Control Systems; The Fairmont Press, Inc.: Lilburn, GA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-88173-669-4. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, T. Lessons from open-source software development. Commun. ACM 1999, 42, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guhlin, M. Open Source and ROI: Open Source Has Made Significant Leaps in Recent Years. What Does It Have to Offer Education? Technol. Learn. 2007, 27, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.M. Return on investment for open source scientific hardware development. Sci. Public Policy 2016, 43, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, M.; Hurt, D.E. 3D Printing in the Laboratory: Maximize Time and Funds with Customized and Open-Source Labware. J. Lab. Autom. 2016, 21, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M. Maximizing Returns for Public Funding of Medical Research with Opensource Hardware. Health Policy Technol. 2017, 6, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riehle, D. The Economic Motivation of Open Source Software: Stakeholder Perspectives. Computer 2007, 40, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linåker, J.; Munir, H.; Wnuk, K.; Mols, C.E. Motivating the contributions: An Open Innovation perspective on what to share as Open Source Software. J. Syst. Softw. 2018, 135, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughees, M.H.; Qian, Z.; Shafiq, Z.; Dash, K.; Hui, P. A First Look at Ad-block Detection: A New Arms Race on the Web. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.05841. [Google Scholar]

- Malloy, M.; McNamara, M.; Cahn, A.; Barford, P. Ad Blockers: Global Prevalence and Impact. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM on Internet Measurement Conference-IMC ’16, Santa Monica, CA, USA, 14–16 November 2016; ACM Press: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, M.A.; Arshad, S.; Kirda, E.; Robertson, W.; Wilson, C. How Tracking Companies Circumvented Ad Blockers Using WebSockets. In Proceedings of the Internet Measurement Conference 2018- IMC ’18, Boston, MA, USA, 31 October–2 November 2018; ACM Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 471–477. [Google Scholar]

- Post, E.L.; Sekharan, C.N. Comparative Study and Evaluation of Online Ad-Blockers. In Proceedings of the 2015 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Security (ICISS), Seoul, Korea, 14–16 December 2015; IEEE: Seoul, Korea, 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Pujol, E.; Hohlfeld, O.; Feldmann, A. Annoyed Users: Ads and Ad-Block Usage in the Wild. In Proceedings of the 2015 ACM Conference on Internet Measurement Conference-IMC ’15, Tokyo, Japan, 28–30 October 2015; ACM Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Redondo, I.; Aznar, G. To use or not to use ad blockers? The roles of knowledge of ad blockers and attitude toward online advertising. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Website | Classification |

|---|---|

| google.com | Web search |

| yahoo.com | |

| bing.com | |

| wikipedia.org | Information |

| weather.com | |

| cnn.com | News |

| foxnews.com | |

| nytimes.com | |

| sohu.com | Chinese search/gaming |

| taobao.com | Chinese e-commerce |

| Website | Use of Ad Blocker | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | AdBlock+ | AdBlock+ Percent | Privacy Badger | Badger Percent | uBlock Origin | uBlock Origin Percent | ||

| 1 | google.com | 0.997 | 0.962 | 3.5% | 0.9476 | 5.0% | 0.9889 | 0.8% |

| 2 | yahoo.com | 2.359 | 2.696 | −14.3% | 1.92 | 18.6% | 1.343 | 43.1% |

| 3 | bing.com | 0.799 | 0.532 | 33.4% | 0.5404 | 32.3% | 0.5402 | 32.3% |

| 4 | wikipedia.org | 2.294 | 2.260 | 1.5% | 2.11 | 8.0% | 2.498 | −8.9% |

| 5 | weather.com | 1.491 | 0.993 | 33.4% | 0.9029 | 39.4% | 0.8561 | 42.6% |

| 6 | cnn.com | 3.258 | 3.347 | −2.7% | 2.678 | 17.8% | 2.514 | 22.8% |

| 7 | foxnews.com | 5.647 | 5.550 | 1.7% | 3.776 | 33.1% | 3.602 | 36.2% |

| 8 | nytimes.com | 3.683 | 3.600 | 2.3% | 2.322 | 37.0% | 2.658 | 27.8% |

| 9 | sohu.com | 16.920 | 8.960 | 47.0% | 13.68 | 19.1% | 4.01 | 76.3% |

| 10 | taobao.com | 1.970 | 1.890 | 4.1% | 1.75 | 11.2% | 1.74 | 11.7% |

| Average | 3.942 | 3.079 | 11.0% | 3.063 | 22.2% | 2.075 | 28.5% | |

| SD | 4.779 | 2.551 | 19.7% | 3.850 | 12.5% | 1.176 | 24.2% | |

| t (Globe) [Hours/Year] | t (USA) [Hours/Year] | |

|---|---|---|

| AdBlock+ | 38.9 | 37.7 |

| Privacy Badger | 78.4 | 76.1 |

| uBlock Origin | 100.7 | 97.7 |

| Ey(Globe) [kWh/year] | Sy(Globe) [USD/year] | Ey(USA) [kWh/year] | Sy(USA) [USD/year] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AdBlock+ | 5.20 × 109 | 728,300,000 | 3.58 × 108 | 45,432,000 |

| Privacy Badger | 1.05 × 1010 | 1,469,800,000 | 7.23 × 108 | 91,690,000 |

| uBlock Origin | 1.35 × 1010 | 1,886,960,000 | 9.28 × 108 | 117,710,000 |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pearce, J.M. Energy Conservation with Open Source Ad Blockers. Technologies 2020, 8, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies8020018

Pearce JM. Energy Conservation with Open Source Ad Blockers. Technologies. 2020; 8(2):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies8020018

Chicago/Turabian StylePearce, Joshua M. 2020. "Energy Conservation with Open Source Ad Blockers" Technologies 8, no. 2: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies8020018

APA StylePearce, J. M. (2020). Energy Conservation with Open Source Ad Blockers. Technologies, 8(2), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies8020018